By Flint Whitlock

It was March 7, 1945––a gray, overcast day with a nasty chill in the air, the kind of day in which a soldier at the front wished he could relax in front of a toasty fire with a canteen cup full of hot coffee and think about home.

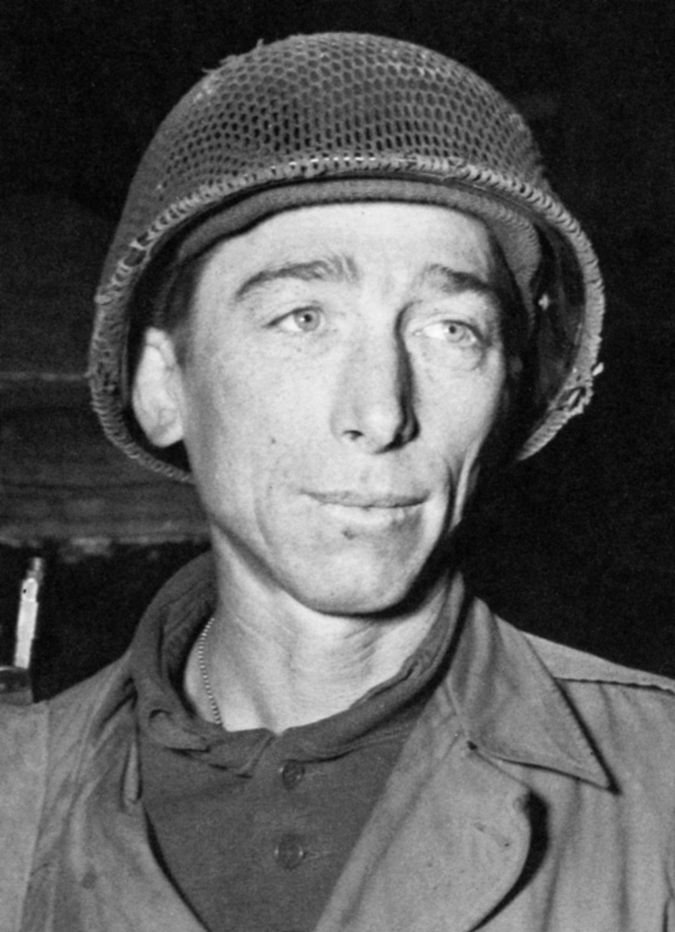

Instead, the members of 2nd Lieutenant Karl H. Timmermann’s Company A, 27th Armored Infantry Battalion, Combat Command B of the U.S. 9th Armored Division were lying in the mud and wet weeds at the edge of the Rhine River, staring at a 1,056-foot-long stone and steel bridge that had death written all over it.

Timmermann had been promoted to company commander just hours before, after the previous commander, Captain Frederick F. Kriner, became a casualty during the fighting at Stadt Meckenheim, a few miles west of Remagen, the previous day.

His division, nicknamed the “Phantom Division,” had been in Europe ever since arriving in France on October 3, 1944. It had seen heavy combat during the December German counteroffense in the Ardennes, and elements of the division had taken part in the defense of St. Vith and Bastogne. In late February 1945, under III Corps control, the 9th had participated in Operation Lumberjack, the Allied drive out of the Ardennes/Eifel area and into Germany. Although their time in combat had been relatively brief, the men were worn out and battle weary.

They were wary, too, for it seemed that the retreating German army they had been pursuing was on the verge of collapse. It seemed foolish, even stupid, to take any unnecessary risks now that the war was as good as over.

Yet, here was their company commander, a German-born, 22-year-old resident of West Point, Nebraska, telling them they had to get up from their places of relative safety and start across this structure that just smelled of an ambush, a trap. At the near and far ends of the span, dark, medieval-looking stone towers stood watch, almost beckoning the Yanks to come across, like the mythical Lorelei of the Rhine, leading sailors to their doom.

What would happen then, the soldiers wondered. Would hidden machine guns suddenly burst to life, raking the exposed troops with deadly bullets? Were tons of explosives emplaced below the girders, with the firing mechanisms set to go off as soon as the entire company was in the center of the bridge? Was an artillery barrage about to be unleashed upon the unprotected men?

But orders were orders. The division commander, Maj. Gen. John W. Leonard; the Combat Command B (regimental) commander, Brig. Gen. William M. Hoge; and Timmermann’s battalion commander had all given the word: Take that bridge at all costs.

It wasn’t that bridges along this stretch of the Rhine were in abundance. Those that had been standing had become the only escape route for the retreating German forces. But all of them were now nothing but rubble.

Since the beginning of warfare, rivers, oceans, and mountains have presented natural obstacles for advancing, or retreating, armies. By World War II, this was still true, but nature had, to a great extent, been conquered by technology and man’s ingenuity.

Germany is striped vertically by an abundance of rivers than run, generally speaking, from south to north: the Ahr, Ruhr, Roer, Kyll, Main, Mosel, Nahe, Neckar, Erft, Ems, Elbe, Weser, Oder, Donau (Danube), and, most importantly, the Rhine.

In Roman times, the Rhine was considered the northernmost frontier of the Empire (excluding Britannia), and divided Gaul from Germania.

The Rhine, Germany’s longest river and its great natural barrier in the west, begins as a swiftly moving stream at the Rheinwaldhorn Glacier, more than 11,000 feet above sea level, near Andermatt in the Swiss Alps, and flows north and east for approximately 820 miles, until it empties into the North Sea at Amsterdam. Five hundred miles of it is navigable by large boats and ships. By the time it reaches Germany, the Rhine is a broad waterway a mile wide in places.

After Nazi Germany’s costly failure in its last major counterattack in the west known as the Battle of the Bulge, what was left of the Wehrmacht was rolling eastward into the heart of the Fatherland, hoping to put the mighty Rhine between it and the advancing British and Americans.

But the Americans and British had come to Europe prepared. The U.S. Army had within its organization specialized brigade- and regiment-size engineer units whose job it was to build bridges––whether of the Bailey or pontoon variety––across otherwise impassable rivers and streams. Other engineer units carried with them collapsible rowboats that could be powered by paddles or outboard engines. But crossing wide rivers presented a special challenge, and commanders always preferred to capture a bridge intact rather than have to spend the hours or sometime days to construct one from scratch. That the Allies failed to do so at Holland’s Rhine bridge at Arnhem the previous September was testimony to the ferocious defense the enemy was expected to put up.

Aware that the Rhine posed the last major geographic obstacle to Allied troops, and aware that he still had substantial numbers of forces west of the Rhine, German dictator Adolf Hitler ordered the bridges over the river destroyed.

Unfortunately for the Germans, their unwieldy command structures were often confusing and contradictory, making a coordinated defense unlikely. At Remagen, Captain Willi Bratge was the so-called combat commander of the area; his authority, however, was only valid in the event of emergency. Another captain, Karl Friesenhahn, was the technical and bridge commander, in charge of blowing up the structure to prevent it from falling into enemy hands. Major Hans Scheller, adjutant of LXVII Corps, which controlled the Remagen area, had authority over both Bratge and Friesenhahn.

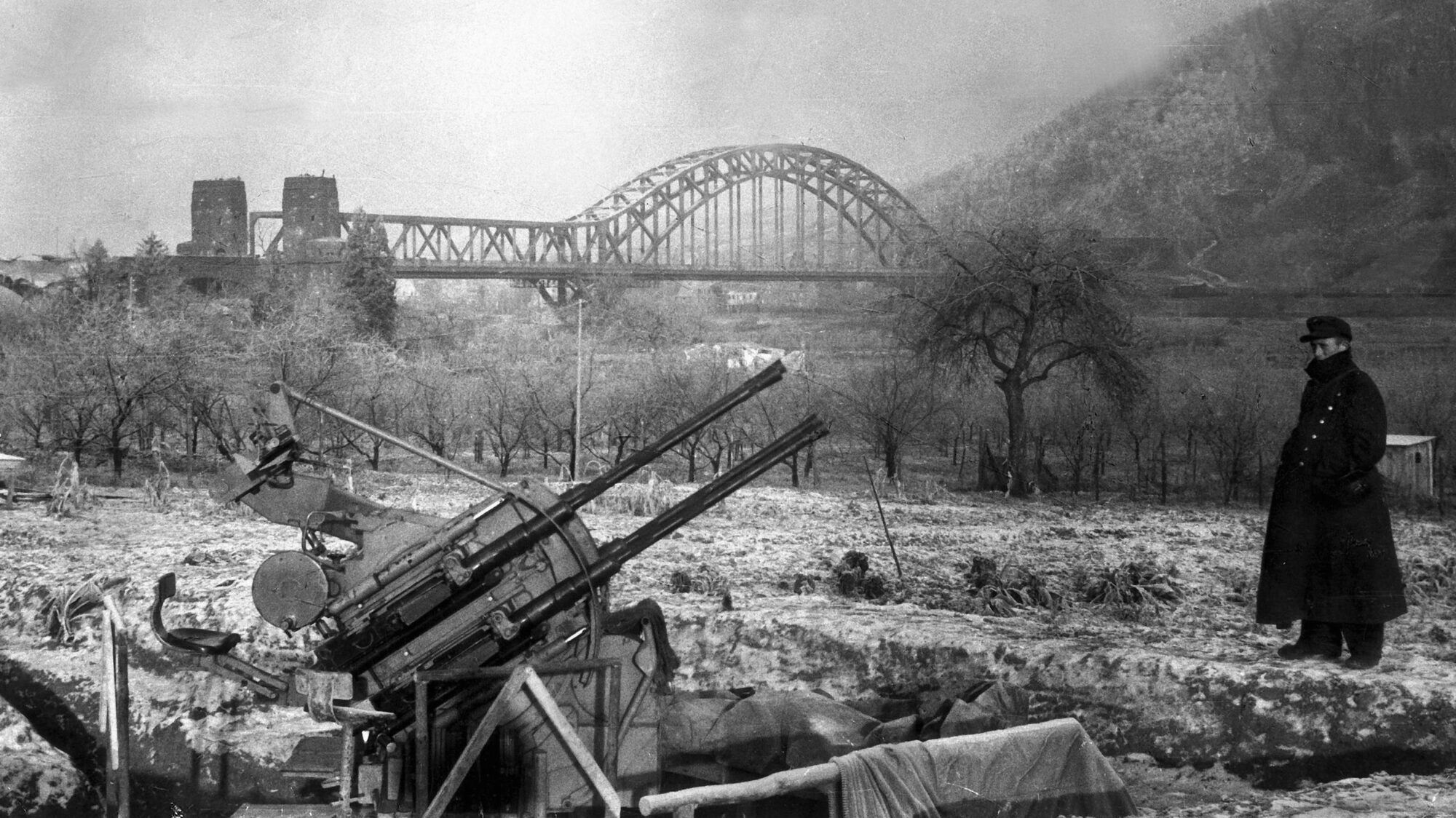

An antiaircraft unit commander––a member of the Luftwaffe, who was not under the authority of either Bratge or Friesenhahn––had the responsibility of guarding the bridge against Allied air forces. Further, Volksturm forces (a paramilitary organization made up of armed, minimally trained civilians) in the area were controlled by Nazi Party officials.

To add another layer of bureaucracy on top of the already convoluted situation, the U.S. Army’s official history of the ETO campaign says, “Prior to March, responsibility for protecting the Rhine bridges had rested entirely with the Wehrkreise (military districts). Troops of the Wehrkreise were responsible not to any army commander but to the military arm of the Nazi party, the Waffen-SS, and jealous rivalry between the two services was more the rule than the exception.”

Recent command changes at the army and army group levels, and an exchange of zones of responsibility (including the responsibility for the Remagen bridge), also negatively affected the Germans’ ability to meet the growing threat.

But try they did. Some 750 German soldiers were at or near the bridge and Friesenhahn’s demolition experts had installed several hundred pounds of explosives at critical points in the bridge’s superstructure and foundation and wired the explosions to control boxes. But Friesenhahn was under orders not to blow the bridge until the very last moment; thousands of German troops to the west of the Rhine needed it to cross the river and set up defensive positions.

During the first week of March 1945, Lt. Gen. Omar N. Bradley’s 12th Army Group continued to push inexorably eastward through the Eifel region in what was dubbed Operation Lumberjack––a move to capture strategic cities such as Cologne and Bonn and give the Allies a foothold along the west bank of the Rhine.

Bradley was told to be careful not to push too far and too fast, for SHAEF and General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme Allied commander, wanted to keep the front line Bradley shared with Montgomery’s 21st Army Group to the north more or less straight.

Besides, Monty, despite being quietly blamed for the still-bitter failure of his ill-fated Market-Garden offensive the previous September, was about to launch the massive Allied thrust into Germany, an operation scheduled for March 23 and code-named Plunder (which included Operations Turnscrew, Widgeon, and Torchlight––the assault crossings of the Rhine at Rees, Wesel, and south of the Lippe River by the British Second Army––Operation Flashlight by the U.S. Ninth Army, and Operation Varsity, a combined British-American airborne and glider assault). Any sudden or dramatic moves by Bradley’s group could tarnish the sheen of glory that the British-led advance would bestow on Monty’s ego.

Additionally, no one on the American side realistically expected any bridges to be standing by the time the Yanks reached the Rhine.

In his memoir, A Soldier’s Story, Bradley wrote, “Farther north, Collins’ VII Corps had turned south from Düsseldorf toward Cologne where Terry Allen’s 104th Division picked its way into the ruins of that stricken city. [The Allied] Air [Forces] had miraculously spared its ancient Gothic cathedral and, beyond its twin spires, the Rhine washed through the fallen girders of Cologne’s [Hohenzollern] Bridge. This mile-long span had been demolished by the retreating Germans as our troops dodged warily into the outskirts of Cologne. Only its four ugly towers remained to mark its demise.”

He added, “From Düsseldorf to Coblenz a score of heavy bridges collapsed into the Rhine as crews touched off their demolitions. In Düsseldorf the bridges were blown just as American vanguards reached their western approaches. Although eager to secure a Rhine river bridgehead, we had despaired of taking a bridge intact. As far back as England I had resigned myself to the necessity of an assault river crossing.”

Still, in the unlikely event that such an opportunity presented itself, corps and division commanders were given carte blanche to attempt to grab one.

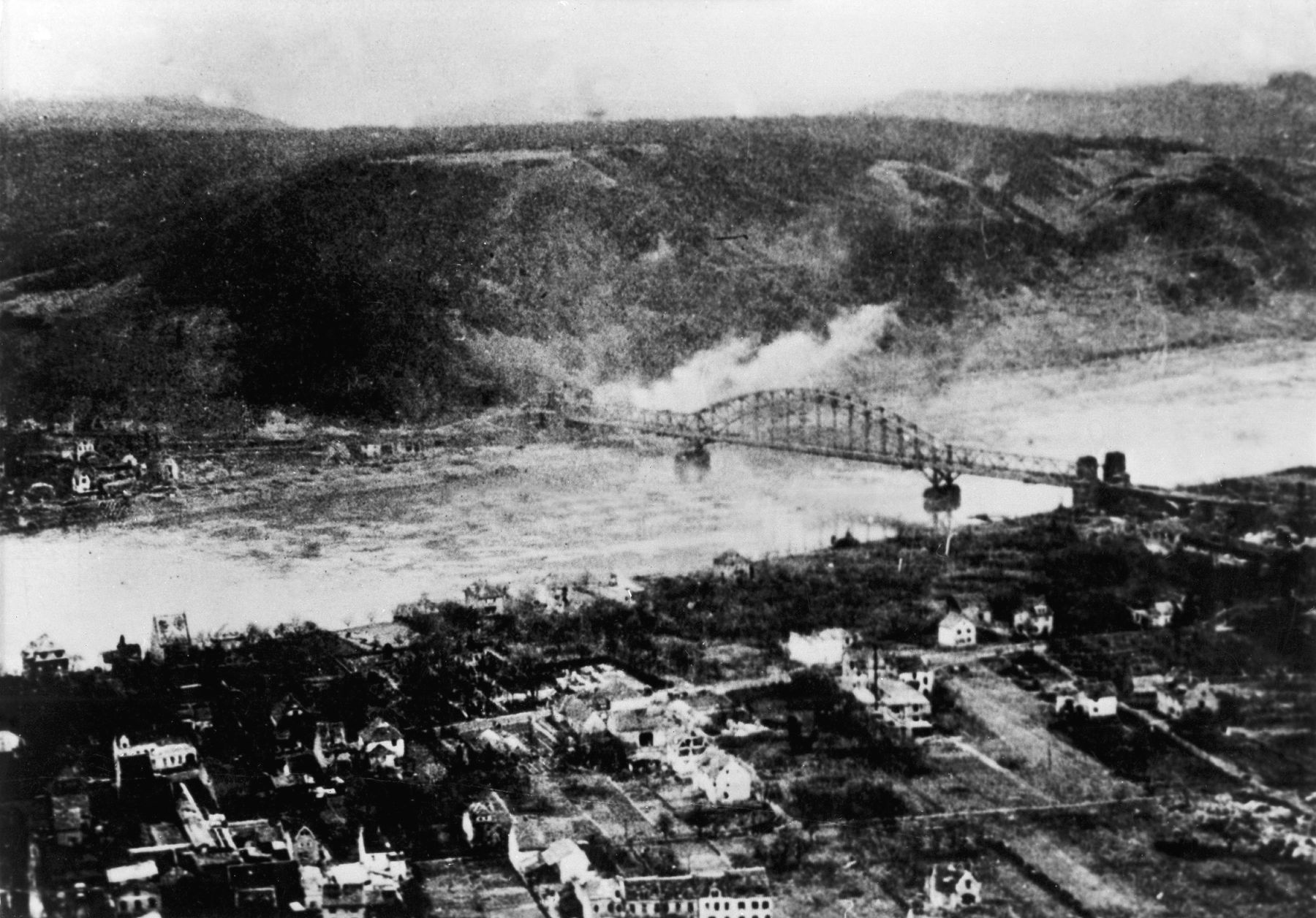

On the morning of March 7, the same day that American troops were moving into the shattered ruins of Cologne, advance elements of the 9th Armored Division reached the heights overlooking the Rhine and the town of Remagen, 15 miles south of Bonn.

From their lofty perch, the Yanks were stunned to see a major bridge––the Ludendorff Bridge––still standing. A quick check of the maps showed that the railroad bridge connected the villages of Remagen and Erpel on opposite sides of the river.

Designed by Karl Wiener and built during World War I by the firm Grün und Bilfinger, the Ludendorffbrücke allowed the Kaiser’s troops quick access to invade Belgium and France.

Named for the German World War I general Erich Ludendorff, one of the bridge’s proponents (and, as it turned out, an early Hitler supporter), it was one of three railroad bridges built over the Rhine during the Great War––the other two being the Hindenburg Bridge at Bingen and the Urmitz Bridge near Koblenz.

The Ludendorff Bridge was 1,056 feet long, with two rail lines and a walkway; the tracks recently had been planked over to provide a roadbed for vehicular traffic. It had three spans of 278, 513, and 278 feet in length, with two heavy stone towers at each end that contained embrasures for machine guns; the four towers could house a full battalion of men.

The Ludendorff Bridge had often been under fire during the past few months. On October 19, 1944, a raid by 33 planes of the Ninth Air Force hit the bridge and erroneously reported they had destroyed it. On December 29, another raid damaged the western, or Remagen, end of the bridge. (At Remagen, the Rhine briefly curves to the west, then resumes its flow to the north. The “west” bank, then, becomes the “south” bank and the “east” bank is now “north”; the bridge runs north and south here, but for purposes of clarity, we shall use the terms “west” and “east.”)

The structure was hit again on January 2, 1945, and once more 26 days later. The Germans were experts at repairing bomb damage, though, and the bridge was quickly put back into operation after each raid.

From atop the bluffs above Remagen, the officers of the 27th Armored Infantry Battalion could see a long line of German vehicles and troops working their way toward and onto the bridge to escape the American advance and thus called for artillery strikes to interdict the traffic. Luckily, artillery support was not forthcoming. When the 27th contacted Brig. Gen. William Hoge, commanding Combat Command B, he immediately drove to the town, surveyed the situation for himself, and ordered the 27th and the 14th Tank Battalion to advance into Remagen in preparation for seizing the bridge.

The town was taken without incident. At 3:15, Company A of the 27th, led by Lieutenant Timmerman, moved cautiously toward the elevated approach to the bridge. The lieutenant had only one question: “What if it blows up in my face?”

At the opposite end of the span, where the tracks disappeared into a large tunnel beneath the hill known as the Erpeler Ley, Captain Friesenhahn saw the Americans advancing and ordered a demolition charge detonated; it blew a 30-foot crater in the elevated roadway.

While Timmermann’s men took cover from the flying debris and from bullets pouring from the gun ports in the towers, Major Scheller gave Friesenhahn the order to blow the bridge.

But, as Ken Hechler detailed in his excellent 1957 book, The Bridge at Remagen, nothing happened when Friesenhahn turned the key that activated the ignition charge; a tank shell must have cut the line. He called for volunteers to dash out into the hail of bullets and shells and light the primer cord for the emergency demolition charge. At first no one volunteered; finally a Sergeant Faust said he would do the job. After crawling nearly a hundred yards to the fuse, Faust set it off and there was a series of tremendous blasts.

It appeared to Timmermann and his men that the bridge had been torn loose from its foundations and would topple into the gray-brown water at any moment. From their prone positions, many of the GIs no doubt breathed a sigh of relief; they had received a reprieve from crossing the deadly bridge.

Within seconds, however, as the smoke cleared, it became obvious that the bridge was still intact. (Only 300 kilograms of the expected 600 kilograms of explosives was available to Friesenhahn, and it was a weaker industrial grade, not the standard military issue. It was also later determined that two Polish conscripts in the German Army had tampered with the fuses, thus reducing the full force of the explosions.)

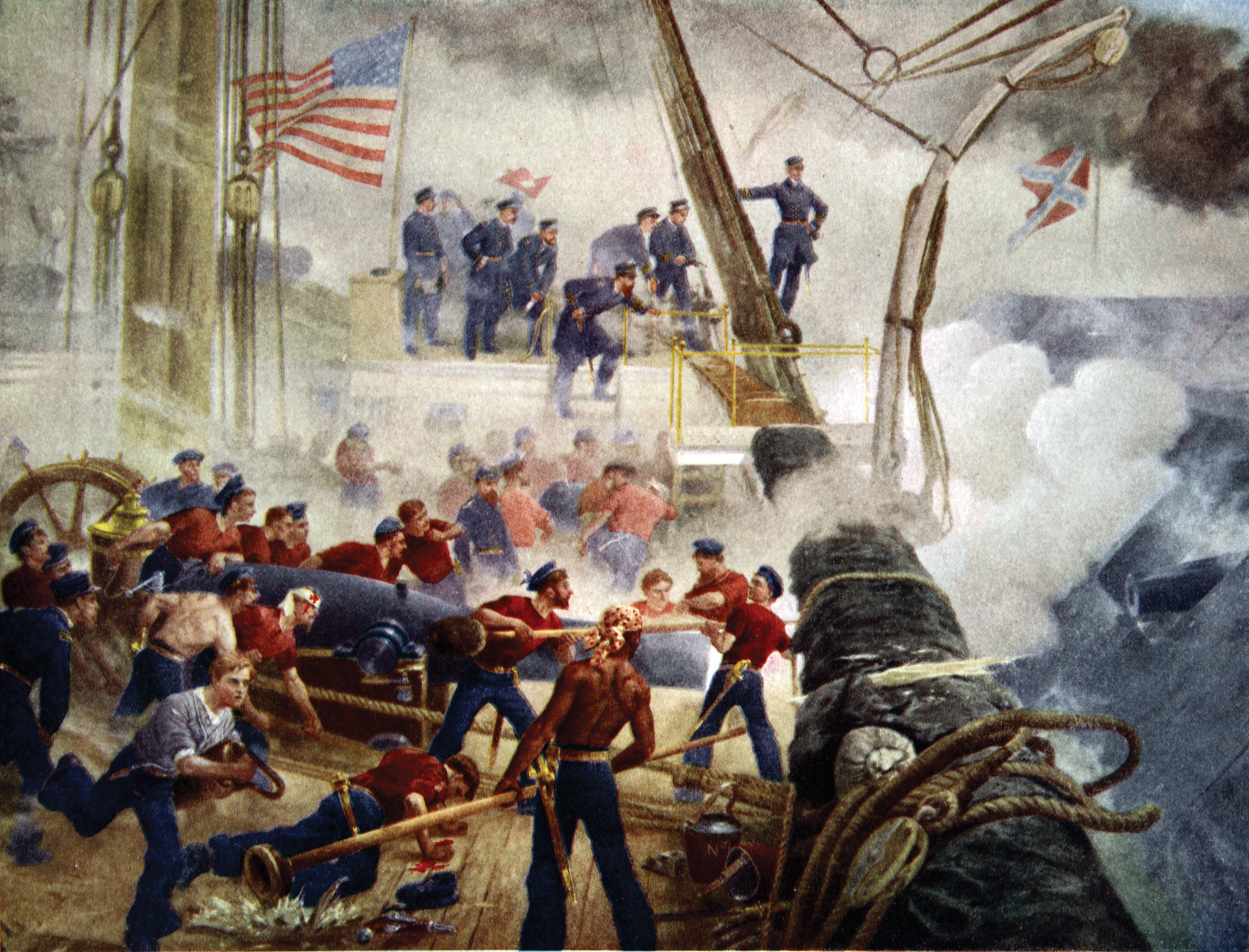

As small-arms and tank fire from a platoon of M-26 Pershing tanks blasted the far side of the bridge, and smoke shells were dropped in to conceal the movement, Timmermann gave the dreaded order to cross the bridge. Squad leader Sergeant Alexander A. Drabik turned to his men and said: “Okay, who’s going with me? I’m going across.”

Summoning all of their courage, Drabik and his men, followed closely by Timmermann, dashed onto the planked-over tracks, ducking instinctively as machine-gun bullets from the opposite bank pinged off the steel framework.

Drabik, from Ohio, was the third-oldest man in the company but he ran the entire length, more than three football fields long, like a halfback, dodging bullets the entire time.

Simultaneously, three other men––Lieutenant Hugh B. Mott and Sergeants Eugene Dorland and John Reynolds from Company B, 9th Armored Engineer Battalion––crawled under the bridge and began cutting the wires that led to some of the demolition charges.

Clemon Knapp, a young soldier from West Virginia, had a Sherman tank with a blade in front of it, known as a “tank dozer.” Under fire, he quickly brought the “dozer” forward to fill in the crater in the approach ramp.

Meanwhile, the tunnel at the eastern end of the bridge was filling with cowering soldiers, civilians, foreign workers, and even animals, as bullets and shell fragments ricocheted off the rock walls. Leaving Bratge in command, Major Scheller exited the tunnel by its rear opening to report to headquarters the failed attempt to blow the bridge.

As the Yanks neared the center of the bridge, German marksmen in a barge on the river opened up on them. Timmermann ran back and ordered a tank to knock out the barge, which it did.

After several minutes that seemed like hours, Sergeant Drabik and his men finally reached the far end miraculously unscathed. Drabik said later, “It wasn’t a historical moment for me. I was too busy running. I didn’t think about the bridge blowing or anything. I just wanted to get to the other side.”

Once Drabik got there, a young German soldier pointed his rifle at him. “The kid looked behind me and saw my whole company coming,” Drabik said, “so he threw down his rifle and surrendered.”

Right behind Drabik was Sergeant Joseph DeLisio, leader of the third platoon. Despite shells from 20mm antiaircraft guns being pumped at them, DeLisio reached one of the towers, burst through the door, and ran up the stairs, taking the two-man gun crew prisoner. DeLisio threw the gun out the window as three of his men entered the other tower and silenced the machine gun there.

With the towers secure, Sergeant Drabik and his squad turned left up the river road and went about 200 yards before they took up defensive positions in a series of bomb craters.

As this was happening, Timmermann sent DeLisio and four of his men into the darkened railroad tunnel. DeLisio fired two shots into it and several German soldiers emerged with their hands up. Not realizing a much larger force lay farther within, along with numerous civilians, DeLisio informed Timmermman that the tunnel was clear.

Timmermann called for reinforcements and higher command responded by sending tanks and more infantry across. But, due to damage to the bridge’s planked roadway, the first tanks would not cross until midnight, after engineers had plugged the holes.

The engineers had also followed Timmermann’s company to find and cut any other lines leading to the explosive charges. Sergeant Dorland saw a thick cable and tried but failed to sever it with a small pair of wire cutters so, unslinging his carbine, he fired three shots into the line, blowing it apart.

By now, around 4:00 pm, Timmermann had about 120 men across, but the high ground above the bridge’s eastern terminus was still, as far as he knew, in enemy hands. He ordered 2nd Lieutenant Emmett J. Burrows to take the second platoon up the steep Erpeler Ley. Climbing was difficult, and several men were injured when they slipped and fell on the loose rock. Enemy shelling also caused a number of injuries and only a few of Burrows’s men reached the top. Once there, they cleared out snipers in a house on the hillside and saw groups of Germans in nearby foxholes, with many more in the neighboring towns down below, possibly preparing for a counterattack. Burrows and his men suddenly came under terrific artillery and mortar fire; to the GIs, Erpeler Ley became known as “Suicide Cliff” and “Flak Hill.”

Taking the bridge had been a close-run thing; had the Germans mounted a serious counterattack with tanks and infantry, Timmermann and his men might have been wiped out.

In the meantime, the Americans had something new to worry about.

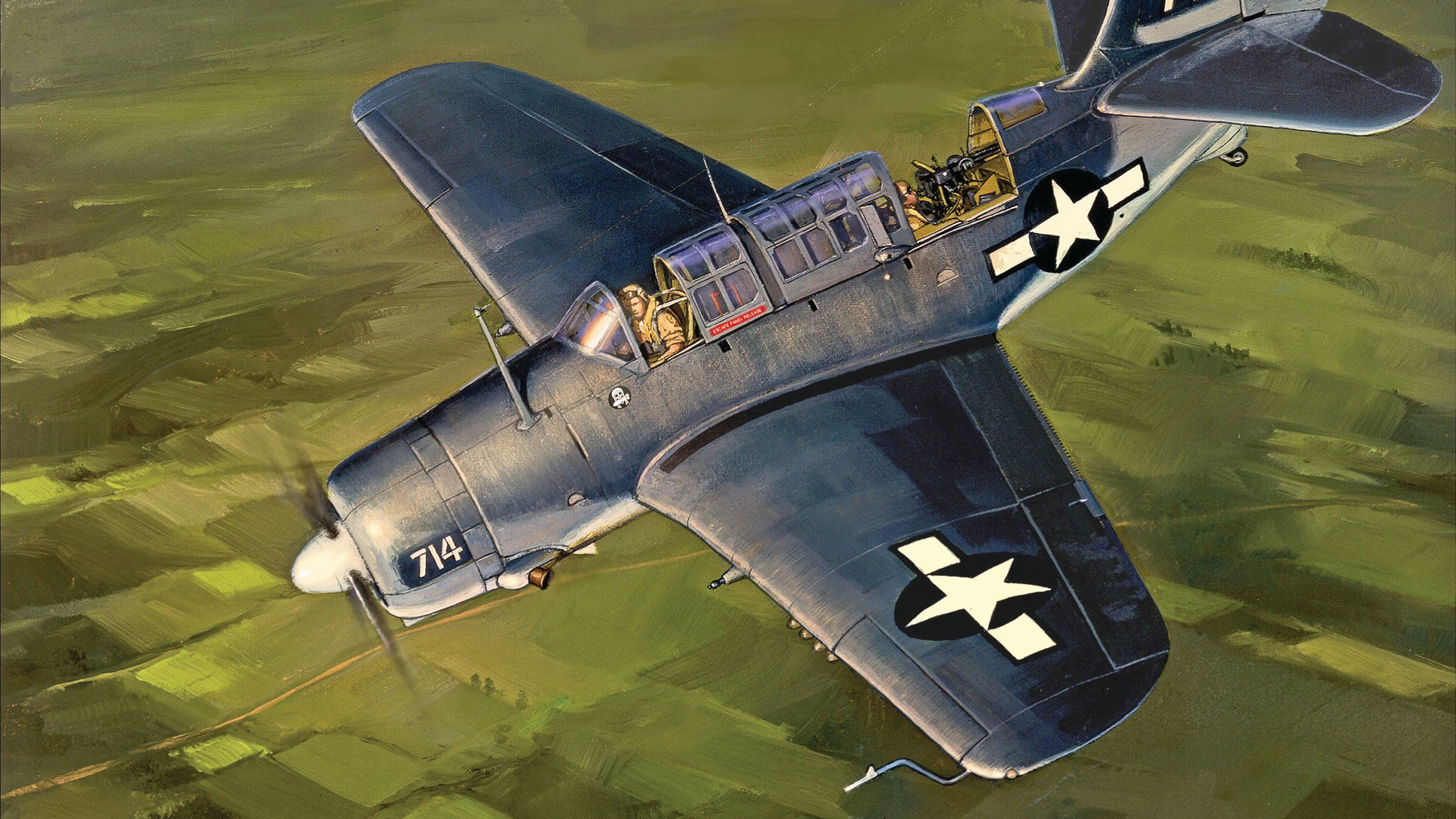

The first aerial counterattack came at 4:45 pm on the 7th. Three obsolescent Ju-87 Stuka dive-bombers and one Me-109 fighter made a low-level pass at the bridge. Major Ben J. Cothran, the S-3 of the 9th’s CCB, described the action:

“That afternoon the first planes came in for the bridge. But Pappy [Captain Carlton G. “Pappy” Denton, commander of Battery D, 482d AAA Battalion (AW/SP)], who had done wonders in the Bulge, had got his anti-aircraft battery together somehow, brought it through all the snarled traffic and was there. Because of high hills … the planes had to make a straight run up the river for the bridge. Four tried it that afternoon. Pappy’s lads got all four.”

Although Cothran attributed the anti-aircraft success to Battery D, some of it was provided by Battery A.

Thirty minutes later, the gunners got another opportunity to demonstrate their marksmanship skills. Eight more Stukas swooped down single file. The shrieking dive-bombers that had helped the Germans conquer many a nation plunged nearly straight down, almost guaranteeing a perfect strike.

But the pilots hadn’t figured on the accuracy of Yanks sitting behind their guns. These AA units had been battling the enemy––in the air and on the ground––since the middle of June when they came ashore at Normandy. They had supported the tanks and infantry across France, into Paris and Belgium, and had refused to yield when Hitler threw his massive December counteroffensive at them during the Battle of the Bulge. By this stage of the war, the gunners were “old hands” at the game and not easily panicked by the sight and sound of enemy warplanes.

As the eight Stukas approached from the south, cruising above the river at 3,000 feet, the gunners’ radar easily picked them up and the 90mm guns and quad-50s opened up. Despite the storm of AA fire, the bombers came in straight and level, taking no evasive action. Some jettisoned their bombs before reaching the bridge, and one bomb fell on the western approach to the bridge––that would be as close as the Luftwaffe would come to hitting the structure. The gunners knocked all eight aircraft out of the sky. Battery B, 413th AA Battalion, was credited with four kills.

Also on that same day, the Luftwaffe used its jets––Me-262 fighters and Arado AR-134 bombers–– against the bridge for the first time. Because the jets flew at speeds of around 400 miles per hour, the AAA gunners had difficulty acquiring and tracking them. Fortunately for the Americans, the jets were ineffective.

At about 5:30 pm, as the last aerial attack of the day was ending, Timmermann and his men guarding the eastern end of the bridge were startled to see Captains Bratge and Friesenhahn and their men emerge from the tunnel in no mood for a fight; they were all taken prisoner and marched back across the bridge to captivity.

That night a group of German engineers counterattacked with the hope of blowing the bridge with their explosives, but all were killed or captured by GIs from the 9th Infantry Division who had crossed on the heels of Timmermann’s company.

As the consolidation at the eastern end of the bridge was taking place in the gathering twilight, Hoge reported to his division commander, Leonard, “Well, we got the bridge,” and the news of its capture was passed up the chain of command.

That evening, while in a meeting with Maj. Gen. Harold R. Bull, the SHAEF operations officer, Bradley was interrupted by an urgent call from Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges, commander of First Army.

“Brad, we’ve got a bridge,” Hodges said excitedly.

“A bridge? You mean you’ve got one intact on the Rhine?”

“Yep. Leonard nabbed one at Remagen before they could blow it up.”

“Hot dog, Courtney!” Bradley exclaimed. “This will bust him wide open. Are you getting your stuff across?”

“Just as fast as we can push it over,” Hodges replied. “Tubby’s [Brig. Gen. Truman C. Thorson, First Army operations officer] got the navy moving in now with a ferry service and I’m having the engineers throw a couple of spare pontoon bridges across to the bridgehead.”

“Shove everything you’ve got across it,” ordered Bradley.

Bull was not all that thrilled by the news, realizing that the effort to take advantage of this unexpected development would disrupt SHAEF’s long-awaited, carefully crafted operation that called for Montgomery and his 21st Army Group to make the major Allied crossing of the Rhine in the Ruhr industrial area (Operation Plunder). As usual, Montgomery was taking his sweet time, meticulously planning for the operation, building up his forces, and preparing to siphon off units from Bradley’s army group for his own use. Such a change in plan was sure to anger him.

“Sure, you’ve got a bridge, Brad,” Bull said, “but what good is it going to do you? You’re not going anywhere down there at Remagen. It just doesn’t fit into the plan.”

“Plan, hell! A bridge is a bridge and mighty damned good anywhere across the Rhine!”

Bradley saw that a Rhine crossing at Remagen most likely would distract the German command and cause Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, commander in chief of German forces in the west, to pull units from the area of Montgomery’s planned attack to counter the Remagen crossing.

For his part, Bull knew that, while Eisenhower had not yet decided to restrict the number of Rhine crossings, Ike favored Montgomery conducting the main attack farther north. When Bull brought this up, Bradley fumed, “What in the hell do you want us to do––pull back and blow it up?

To settle the matter, Bradley called Ike at his headquarters in Reims, France. “When he reported that we had a permanent bridge across the Rhine,” Ike wrote in his 1948 best-selling memoir, Crusade in Europe, “I could scarcely believe my ears. He and I had frequently discussed such a development as a remote possibility but never as a well-founded hope.”

Ike asked, “How much have you got in that vicinity that you can throw across the river?”

“I have more than four divisions, but I called you to make sure that pushing them over would not interfere with your plans.”

“Well, Brad, we expected to have that many divisions tied up around Cologne and now those are free. Go ahead and shove over at least five divisions instantly, and anything else that is necessary to make certain of our hold.”

“That’s exactly what I wanted to do, but the question has been raised here [by Bull] about conflict with your plans, and I wanted to check with you.”

Ike noted, “That was one of my happy moments of the war…. This was completely unforeseen. We were across the Rhine, on a permanent bridge; the traditional defensive barrier to the heart of Germany was pierced. The final defeat of the enemy … was suddenly now, in our minds, just around the corner.”

Ike also said, “Here [III Corps] encountered one of those bright opportunities of war which, when quickly and firmly grasped, produce incalculable effect on future operations.”

Bradley realized that the Remagen area would soon become congested, and thus vulnerable to air attack, and told Hodges that he could expand the bridgehead 1,000 meters per day to prevent the Germans from digging in on the opposite bank, extensively mining their perimeter, or bringing in any sizable reinforcements. Hodges began hurriedly diverting resources to Remagen.

American units swarmed into the area. After the 9th Armored Division and 9th Infantry Division crossed, then came the 78th and 99th Infantry Divisions, with more on the way. Leo J. Ghirardi, a sergeant with L Company, 394th Infantry, 99th Division, had vivid memories of the night his unit marched south from Cologne and crossed the bridge: “We walked most of the night along the banks of the river. However, as we approached the bridge at Remagen, the Germans were firing their 88s over to our side of the river.

“I wasn’t alone when I felt the fear of death as those 88s kept coming in so near to my platoon. I will never forget jumping into a ditch of water and soft mud in an attempt to get away from them. There I was, covered with mud from head to foot. That I could live with. But when I discovered my M-1 rifle filled with mud, I knew I had to find a clean one and fast. I got one from a jeep driver as we crossed the river. I was still afraid that I would not be able to hit a target with it because I had never zeroed this rifle in.

“After that eventful dip in the ditch, we soon were approaching the embankment that led to the rail line. Believe it or not, I thought we would make a mad dash across the bridge, but our company commander gave orders for us to walk across and to be sure to keep our distance. Try to imagine having a migraine headache all day and then finding you have to cross a bridge like this under heavy fire.”

With typical GI humor, someone attached a large sign to one of the towers: “CROSS THE RHINE WITH DRY FEET COURTESY OF 9TH ARMD DIVISION.” (The sign is on display at the Patton Museum of Cavalry and Armor at Fort Knox, Kentucky.)

Within the first 24 hours after the bridge’s capture, over 8,000 GIs and hundreds of tanks and other vehicles indeed crossed the Rhine with dry feet, while combat engineers worked frantically to repair the damaged and weakened structure.

In addition, not knowing how long the unstable Ludendorff Bridge might remain standing, the engineers began building a pair of floating pontoon treadway bridges alongside the main structure. The first bridge was installed in just 10 hours and 11 minutes, and Ike gave a couple cases of champagne to Colonel Mason J. Young, head of the VII Corps engineers, as a reward for his men’s timely work.

In actuality, more than “a couple of cases” arrived. A member of the 899th Tank Destroyer Battalion recalled that an entire trainload of champagne showed up at the Remagen railroad station. “I got my ration,” the soldier noted, “––a box of twelve bottles wrapped carefully in straw. Since we did not have a basic load of 90mm rounds stored in our M-36 tank destroyer, I found space in the ammunition racks for several bottles of French champagne.”

Yes, the Americans had secured a foothold on the east bank of the Rhine, but it was a tiny, tenuous foothold, and no one could predict how long it could last.

The Germans were about to try and take it back.

One of the primary tasks for the Americans was to discourage German air attacks. To this end, Bradley called upon nearly every antiaircraft artillery unit under his command to rush to Remagen and blanket the countryside with AAA guns. If the Luftwaffe tried again to destroy the bridge, they would have to fly through a wall of flying lead and steel to do it.

By dawn on March 9, less than 30 hours after its capture, there were five antiaircraft artillery battalions defending the Remagen bridge.

On that day, the Germans came at the bridge with a variety of different planes––everything from Fw-190s and Me-109s to Me-210s and He-110 bombers. The Germans also changed their tactics. They intensified their artillery bombardments to coincide with their air attacks. Seventeen aircraft attacked singly and randomly, taking evasive action as the AAA fire commenced. Some aircraft skimmed in just above the river; on another occasion two Fw-190s and one Me-109 circled the bridge at 1,200 feet before diving and releasing their ordnance, then climbed up into the clouds. The pilots missed the bridge.

Still, it was not until March 10 that the number of antiaircraft artillery pieces and machine guns approached an overwhelming number. Some planes, however, still managed to penetrate the screen.

As the M-36s of Company B of the 899th rumbled across the bridge on March 10, the champagne-toting TD man noted, “German artillery blew up a truck ahead of us and the one-way traffic was blocked. At high noon I looked up into the sky and saw a lone Stuka dive-bomber release a bomb angling for the bridge. I stood up in the open turret of the TD and filled my canteen cup with champagne and said, ‘Drink up men … this is it.’ The bomb missed. One of the rounds of 14 antiaircraft battalions blew up the Stuka a hundred feet over the bridge.

“I filled my canteen cup two more times, and repeated the same toast. Two more bombs were aimed at the bridge; they missed over or under. Two more Stukas were blown up over the bridge. We crossed the bridge that afternoon. I was glad I didn’t have to drive the TD, let alone load the gun, since, as the TD crew’s 90mm weapons leader, I was well ‘loaded.’”

By the 14th of March, the ring of anti-aircraft weapons in the vicinity of Remagen reached its peak: 16 gun batteries and 33 AW batteries, for a total of 672 anti-aircraft fire units. The Luftwaffe had sent in 367 planes to destroy the bridge; none succeeded, and 106 of them were shot down. Over the course of the next three weeks, the stalwart defense of the Remagen bridge ranks as one of the greatest antiaircraft artillery successes in American military history.

In fact, there might have been too much antiaircraft fire. One officer reported, “The volume of fire was so great … there were over 200 friendly casualties from the AAA .50-caliber rounds returning to the ground. They had accomplished their mission; the German Air Force never touched the bridge.”

On March 12, the Ludendorff Bridge had become too dangerous and unstable to use and, with the success of the two pontoon bridges, it was closed while engineers from the 51st and 291st Engineer Combat Battalions worked to strengthen it.

Desperate to destroy the bridge and stop the unending olive-drab flow of American troops across it, over the next two weeks the Germans increased their air raids and the area came under repeated ground attacks by the German 9th and 11th Panzer Divisions and was bombarded by 88mm guns and the huge 540mm self-propelled “Karl” siege howitzer. It was even targeted by 11 V-2 missile attacks launched from the Hellendoorn area of the Netherlands, about 120 miles north of Remagen, destroying a number of nearby buildings and killing at least six American soldiers. But the shells and missiles all missed the bridge, and the panzers and accompanying infantry could not penetrate the ever-growing perimeter the Americans had thrown around the area.

On March 17, the battered old bridge finally succumbed to its wounds and all the near misses. At about 3:00 that afternoon, there was heard a terrible sound of steel screeching and rivets popping as the bridge twisted and collapsed into the icy waters of the Rhine, carrying with it engineers and members of the 639th AAA Automatic Weapons Battalion. Twenty-eight of the 200 men working on the bridge were killed and 93 others were injured.

That night, six specially trained German frogmen, using oil barrels as flotation devices and carrying underwater explosives, floated downstream with the intent of destroying the pontoon bridges, but powerful searchlights picked them up before they reached their objective and they were captured.

In the aftermath of the “Miracle of Remagen,” General Eisenhower’s chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Walter Bedell Smith, termed the Remagen bridge “worth its weight in gold.” Combat Command B of the 9th Armored Division was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation and both Timmermann and Drabik were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for their heroic deeds.

Time magazine called it “a moment in history” and Ike declared, “The whole Allied force is delighted to cheer the First Army whose speed and boldness have won the race to establish the first bridgehead over the Rhine. Please tell all ranks how proud I am of them.”

On the other side, on March 10, 1945, an enraged Hitler appointed Generalleutnant Rudolf Hübner head of Fliegendes Sonder-Standgericht West, or “Flying Special Court-Martial West,” and ordered the arrest, trial, and execution of those officers he thought responsible for the loss of the Ludendorff Bridge. The next day, Majors Hans Scheller, Herbert Strobel, and August Kraft, along with Lieutenant Karl-Heinz Peters, were summarily court-martialed, lined up in front of a firing squad in the woods near Rimbach, and executed.

Hitler also sacked Field Marshal von Rundstedt, replacing him as commander in chief in the west with Field Marshal Albert Kesselring (who declared with uncharacteristic pessimism, “We have suffered unnecessary losses and our present military situation has become nearly catastrophic.”). General Richard von Bothmer, the commandant of the Bonn and Remagen area, committed suicide.

Only Bratge and Friesenhahn survived, as they had been captured by the Americans before they could be arrested.

The victory at Remagen was not cheap. In the 17 days that the “official” battle lasted (March 7-24), the combined casualties for III and VII Corps were about 860 killed, a nearly equal number missing, and 5,700 wounded.

During that same period, the Germans had even heavier casualties, including more than 11,700 taken prisoner.

The Army’s official history of the operation says, “The capture of the Ludendorff railway bridge and its subsequent exploitation was one of those coups de theatre that sometimes happen in warfare and never fail to capture the imagination. Just how much it speeded up the end of the war is another question.”

But author Hechler said, “The surprise crossing of the Ludendorff Bridge probably saved 5,000 American lives that otherwise would have been lost by an assault crossing of the river.”

Although some historians have downplayed the tactical and strategic value of the seizure of the Ludendorff Bridge, it undoubtedly had a great psychological impact on the Allies and a decidedly negative one on the Germans. In less than two months, Hitler would be dead by his own hand, Nazi Germany would collapse, and the war in Europe would at last be over.

A brief epilogue is called for. In the bridge towers on the Remagen side is located a peace museum that is open daily from March through mid-November. A small plaque in German near the museum commemorates the bridge and those who fought to both defend and capture it. Translated, it reads: “Built for war, destroyed in war. The towers will always remain. Here fought soldiers of two great nations. Here died heroes from near and far.”

As for the two main American heroes, Lieutenant Timmermann died of cancer in 1951 and Sergeant Drabik was killed in a car crash in Kansas in October 1993––ironically while en route to a reunion of his old unit, Company A, 27th Armored Infantry Battalion, 9th Armored Division. He was 82 years old.

After the war, ex-Captain Karl Friesenhahn asked the author Ken Hechler if Timmermann and Drabik had received any awards from the U.S. Army and was told that they had both received Distinguished Service Crosses. Friesenhahn replied, “They deserved them––and then some. They saw us trying to blow that bridge and by all odds it should have blown up while they were crossing it. In my mind, they were the greatest heroes in the whole war.”

Flint Whitlock, editor of WWII Quarterly, is the author of several books and numerous articles about the war. He lives in Denver, Colorado.

Thanks for the great map, and excellent photos!