By Mike Phifer

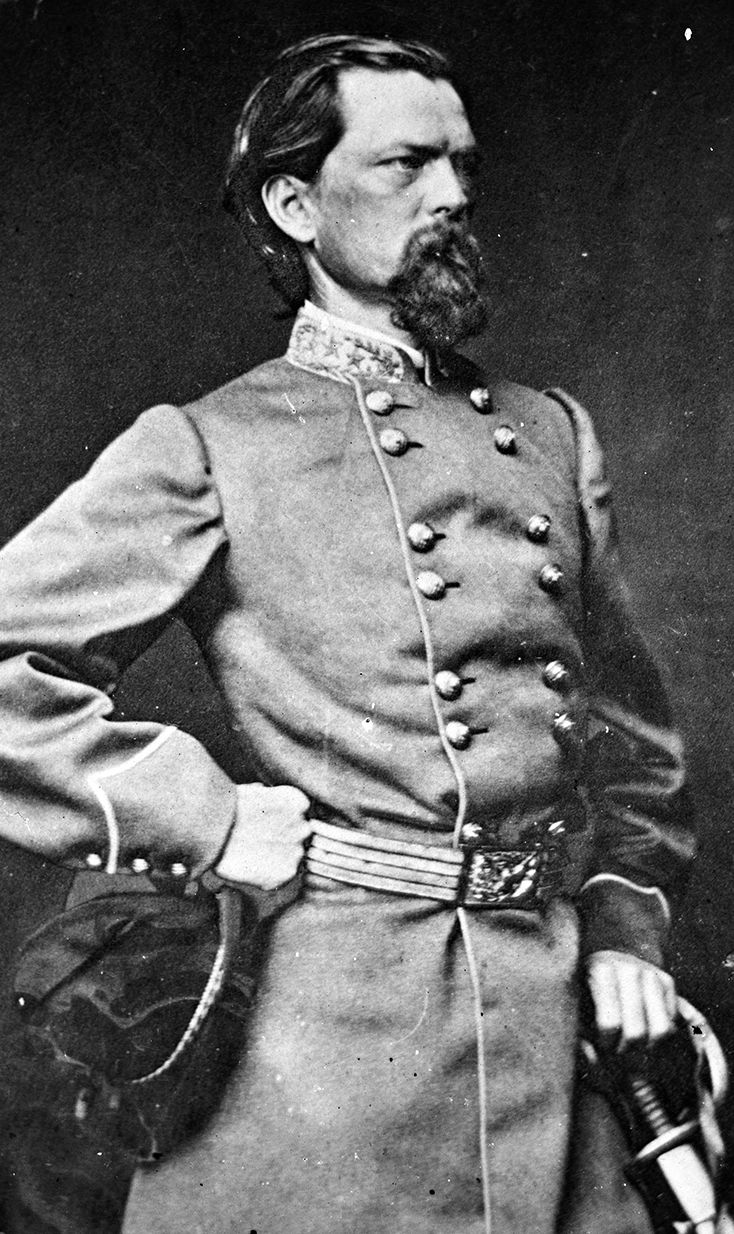

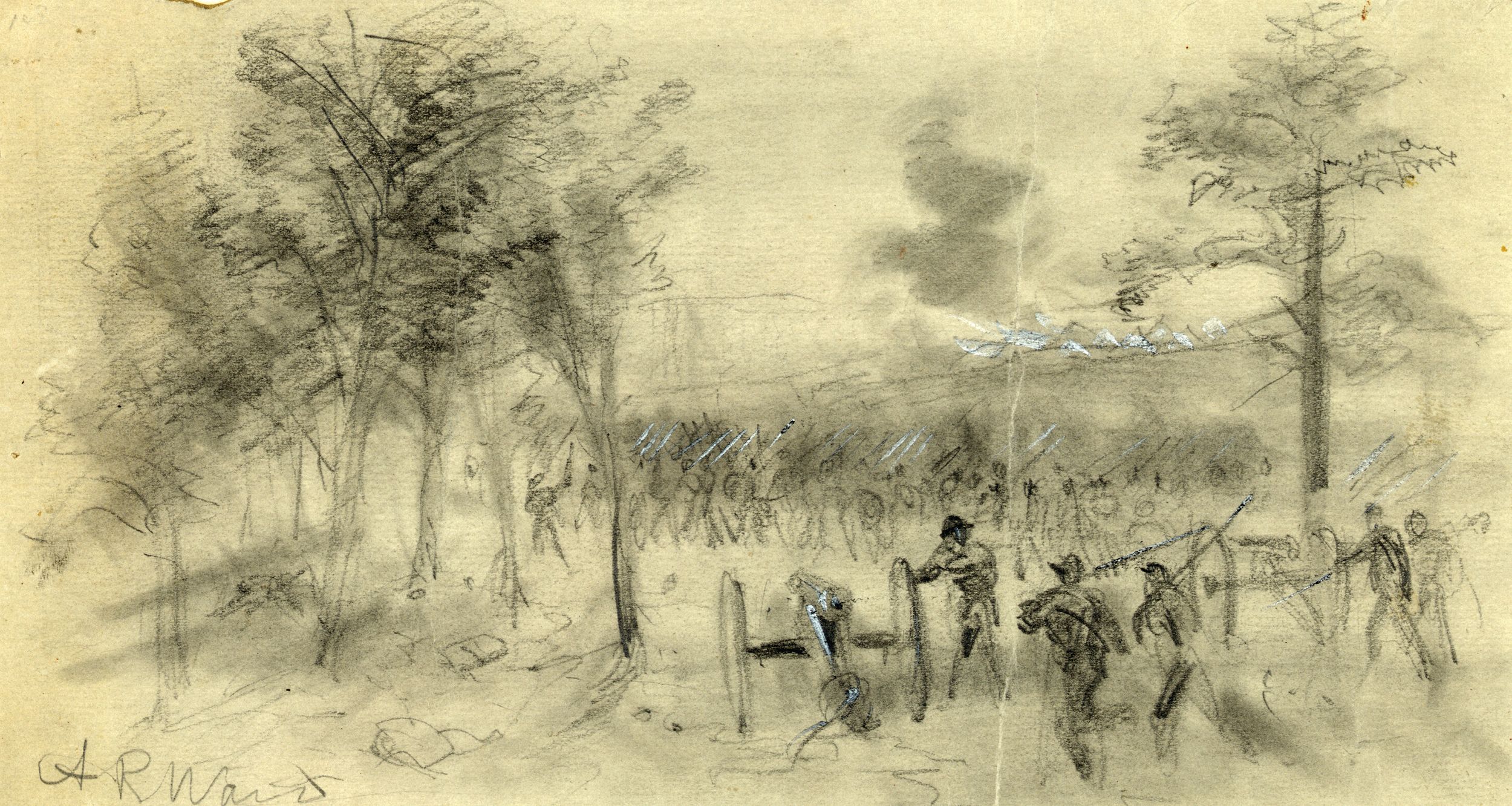

In the early hours of October 19, 1864, fog blanketed the hills and fields along the meandering Cedar Creek in the northern Shenandoah Valley. Federal troops slumbered in their sprawling camps as 3,000 Confederate troops of Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early’s Army of the Valley, clad in ragged gray and butternut uniforms, were silently on the move. Under the command of Maj. Gen. Joseph Kershaw, they slipped through the rough terrain toward the Yankee’s fortified line and waded across Cedar Creek at Bowman’s Mill Ford. While three of Kershaw’s brigades deployed into battle formation, a brigade of Georgians under Colonel James Simms slipped off to silence enemy pickets.

Shrouded by the fog, Simms’ Georgians appeared as dark shadows to pickets of the 5th New York Heavy Artillery, who lit up the dawn with the orange flash of rifle-musket fire before dashing back to camp. The Georgians overran the surprised New Yorkers, capturing 300 of them.

Leading Kershaw’s attack, Simms’ troops pushed on toward the entrenched position of Colonel Joseph Thoburn’s Division. “The works were of a formidable character, with strong abatis covering most of the front and in a favorable position for defense,” recalled Simms. Thoburn’s Federals, many of them half dressed, stumbled out of their tents and loosed a galling volley at the advancing Confederates.

But Kershaw’s Division was unstoppable. With a Rebel yell they crashed over the entrenchment, made free use of the bayonet and routed Thoburn’s Division in about 15 brutal minutes. Kershaw’s men next fell upon a battery of the 1st Pennsylvania Reserve Light Artillery and captured six of its guns. Kershaw’s men quickly swung the heavy 10-pounder Parrotts around and fired on the retreating bluecoats. Battery B, 5th U.S. Artillery was next attacked, but this time the Federals escaped with most of their guns.

To Kershaw’s right, three divisions under Major General John Gordon launched a vicious attack against the Federal left as well. Early’s bold gamble to drive the Union forces from the vital Shenandoah Valley was off to a promising start.

The Shenandoah Valley was no stranger to war. This strategic valley stretches for about 165 miles in western Virginia angling from the southwest to the northeast. Bordering its flanks are the Allegheny Mountains to the west and the Blue Ridge Mountains to the east. Called by some the “Breadbasket to the Confederacy,” its fertile lands helped keep the Confederate forces fed, especially the Army of Northern Virginia. The Valley also served as an invasion route for Southern forces into the north in 1862 and 1863. Federal forces operating in the Valley had not fared well so far in the war. “To many a Federal general it had been the valley of humiliation, on account of the defeats his forces had suffered,” wrote George Carpenter of the 8th Vermont.

Newly appointed General-in-Chief of Union forces, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, would again send Federal forces into the Valley in 1864. Grant planned a major spring offensive. Maj. Gen. William Sherman would advance on Atlanta through northern Georgia, while Grant would accompany Maj. Gen. George Meade’s Army of the Potomac as it advanced overland to Richmond, Virginia. At the same time, the Federal Army of the James would strike at the Confederate capital up the James River. Grant sent a third Federal force in the east under Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel to invade the Shenandoah Valley to sever key railroads supplying Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and force Lee to divert forces to that sector.

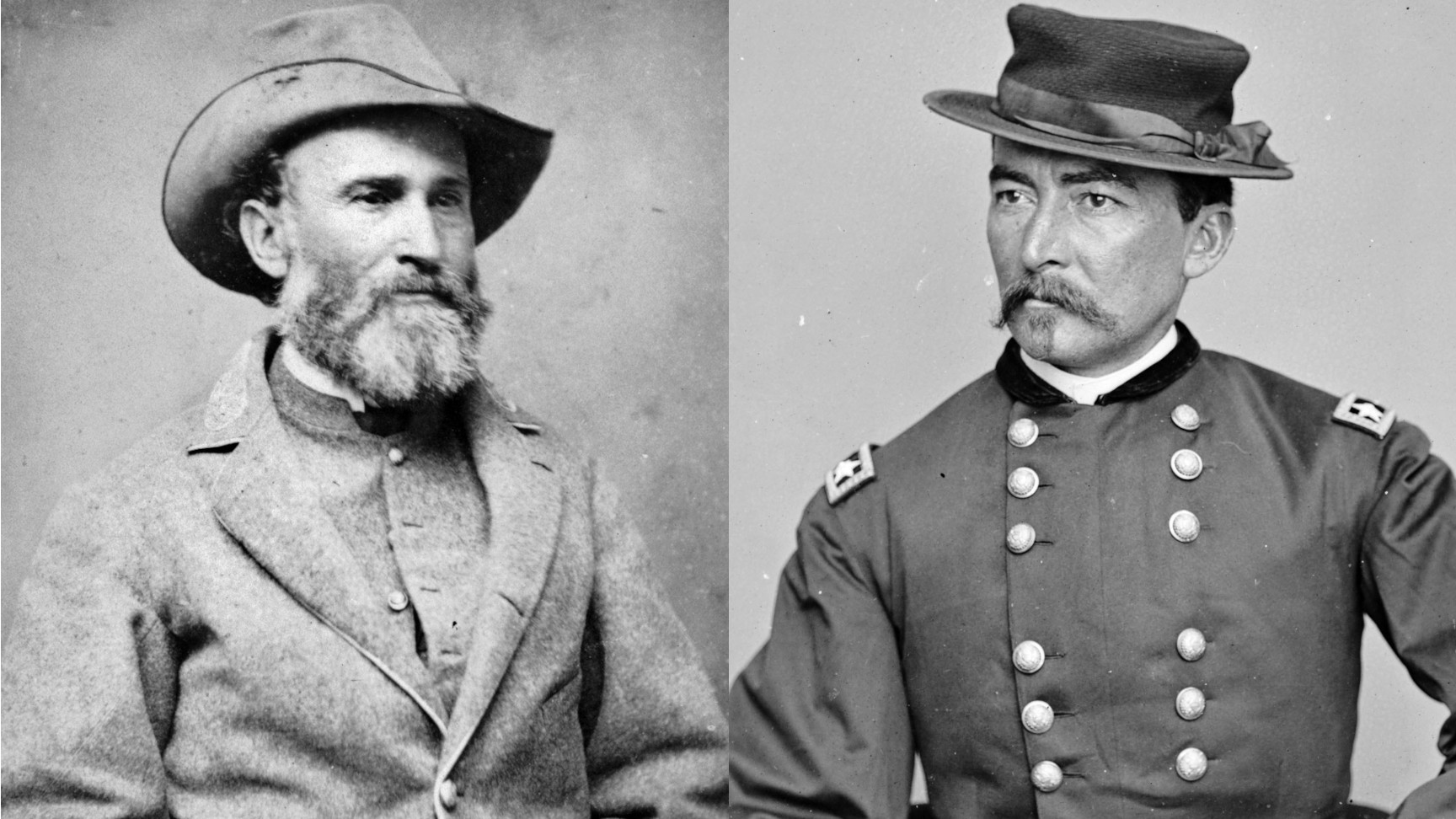

President Abraham Lincoln replaced Sigel, who met with defeat at the hands of the Confederates, with Maj. Gen. David Hunter. Lee entrusted Early to act independently using the corps that he had commanded in the Army of Northern Virginia. Early’s troops defeated Hunter at Lynchburg, Virginia, on June 18, 1864, and drove him out of the Valley. Lincoln demoted Hunter and replaced him with Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan.

Following his victory at Lynchburg, Early marched up the Shenandoah Valley (north), crossed into Maryland, and advanced southeast towards Washington. He ran headlong into a blocking force commanded by Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace at Monocacy Junction. Early triumphed in the July 9 battle, but Wallace’s delaying action allowed large numbers of Union reinforcements to arrive in the capital to boost its defenses. The Confederate commander attacked Fort Stevens, which guarded the northern approaches to the city, on July 11-12. Union major generals Horatio Wright and Alexander McCook soundly repulsed his attack. Early then withdrew back to the Shenandoah Valley to regroup. He took the offensive again, launching a successful attack on July 24 against Brig. Gen. George Crook at Kernstown. Early then launched a raid into Pennsylvania, burning Chambersburg on July 30.

The following day, Grant traveled from Petersburg to Fort Monroe to meet with Lincoln. They decided to consolidate four military departments in Virginia. As part of the reorganization, they gave Sheridan the command of 37,000 troops of the Army of the Shenandoah on August 7. Grant instructed Sheridan to take all provisions, forage, and stock from farms and towns in the Shenandoah Valley to support his army, and to destroy that which Sheridan’s troops could not consume. “It is desirable that nothing should be left to invite the enemy to return,” wrote Grant.

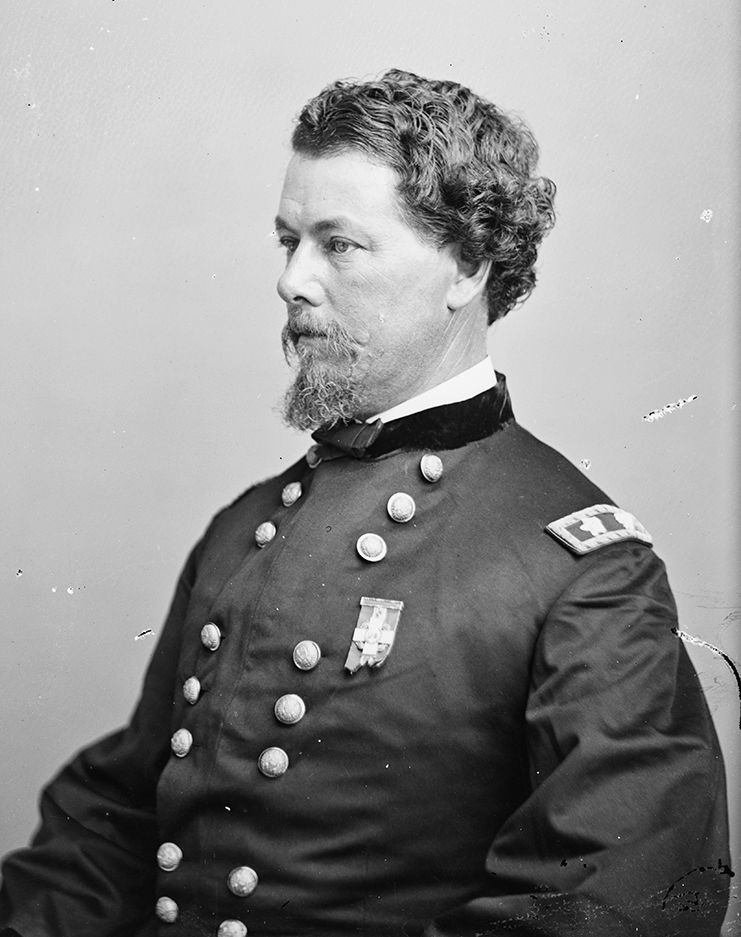

Sheridan’s Army of the Shenandoah comprised Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright’s VI Corps, Crook’s VIII Corps, and two divisions of the XIX Corps transferred east from the Trans-Mississippi Theater, led by Brig. Gen. William Emory.

Sheridan did not wait until all of his forces were assembled. Instead, he immediately marched south with those at hand. For six weeks the two opponents, Early and Sheridan, sparred in the Lower Shenandoah Valley. By mid-August Sheridan held a position at Cedar Creek 15 miles south of Winchester. Sheridan did not like his position. “I cannot cover the numerous rivers that lead in on both of my flanks to the rear,” he complained.

While he halted at Cedar Creek waiting for a supply train to catch up, Sheridan received word from Grant that Confederate reinforcements under Lt. Gen. Richard Anderson were on their way from Lee’s army to join Early. Anderson’s command comprised Maj. Gen. Joseph Kershaw’s Division, Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee’s Cavalry Division, and a battalion of artillery. With these troops on the way and provisions running low as a result of raids on his supply line by Confederate partisans, Sheridan withdrew 40 miles north to Charles Town, West Virginia, where he repulsed a Confederate probe on August 21. The following day Sheridan took up a strong position at Halltown. Deciding Sheridan could not be dislodged from his strong position at Halltown, Early feinted that he intended to invade Maryland. After clashing with Federal cavalry and forcing them to withdraw to the north bank of the Potomac, Early resolved to take up a defensive position at Bunker Hill 12 miles north of Winchester.

Skirmishing occurred through the first part of September with no major engagements, as Sheridan was still careful. He explained after the war that although his forces outnumbered those of Early, he nevertheless had to exercise caution not to incur a defeat on the eve of the 1864 presidential election. Federal authorities in Washington had warned him that a defeat by a Union army in the field might result in the overthrow of the political party in power. Good news, however, arrived to help ensure Lincoln’s reelection when Sherman captured Atlanta on September 2.

Sheridan met with Grant on September 16. The Union commander approved of Sheridan’s plan to go on the offensive upon learning that Anderson and Kershaw’s troops were returning to the Army of Northern Virginia at Petersburg. Three days later Sheridan defeated Early at the Third Battle of Winchester.

Early’s beaten troops retreated a dozen miles to Fisher’s Hill. Sheridan routed Early’s forces with a flanking maneuver on September 22. After his defeat at Fisher’s Hill, Early withdrew 70 miles south to Waynesboro, Virginia, to await reinforcements. Lee once again sent Kershaw’s Division and Rosser’s Laurel Brigade to rejoin the Army of the Valley. Rosser took command of Early’s cavalry after Fitzhugh Lee had been severely wounded at Winchester.

With Early’s defeat, the Federals controlled the Valley as far south as Staunton. Sheridan next turned to the grim task of torching a good part of the Valley. Sheridan’s army marched northward, while his horsemen spread out and lit up barns, mills, and stacks of hay and grain. The skies over the Lower Shenandoah Valley were black with smoke. Sheridan claimed to have burned 2,000 barns, 70 mills, and 435,000 bushels of wheat. The Federals consumed all of the livestock they could eat, and then shot the rest, leaving them to rot in the fields. Although they had succeeded in removing a major source of food stores for the Confederate forces in Virginia, they endangered the lives of the civilians who would have to endure the approaching winter months without sustenance.

Rosser received orders on October 6 to harass Sheridan’s army with his Confederate cavalry brigade. A clash between opposing cavalry unfolded three days later at Tom’s Brook, four miles south of Fisher’s Hill. Sheridan took up a new position on October 10 with 31,000 Union troops on the north side of Cedar Creek. Confident that Early’s Army of the Valley was no longer a menace, Sheridan sent Wright’s VI Corps east to join the Army of the Potomac.

Early, though, was not done yet. After being informed of Wright’s departure, Early decided it was time for his 17,000 troops to strike. Gordon’s division, forming the vanguard of Early’s army, advanced on October 13 to take possession of Hupp’s Hill, just south of the Federals at Cedar Creek. Southern guns soon scattered Yankee troops encamped nearby.

In response, Crook sent two brigades from Thoburn’s Division splashing through the creek to engage the Confederates. Federal artillery opened fire as well. A brigade from Kershaw’s Division joined the fight and helped drive the bluecoats back. Early then decided to pull his army back to Fisher’s Hill.

Sheridan recalled the VI Corps, but after reviewing his position decided that the Confederates likely would remain at Fisher’s Hill. Two days later Sheridan departed for Washington to meet with authorities at the War Department to discuss future operations. He left Wright in temporary command of his army. At the same time, Brig. Gen. Alfred Torbett’s Cavalry Corps set off south on a raid in the direction of Charlottesville.

Wright informed Sheridan that Union troops had intercepted a message from a Confederate signal station stating that reinforcements from Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s I Corps at Petersburg were en route to join Early. Sheridan suspected that the message was a ruse, but as a precaution he ordered Brig. Gen. Wesley Merritt’s First Division and Brig. Gen. George Custer’s Third Division of Torbett’s Cavalry Corps to rejoin the Army of the Shenandoah. He also issued orders for Colonel William Powell’s Second Division to take up a position to the east at Front Royal to watch for Longstreet’s troops.

Sheridan would prove to be right about the message being a ruse. His army, however, would soon be paid a bloody visit by the Confederates. “I was now compelled to move back for want of provisions and forage, or attack the enemy in his position with the hope of driving him from it,” wrote Old Jubilee, adding, “I determined to attack.”

Early dispatched Gordon, Brigadier General Clement Evans, and Major Jedediah Hotchkiss, the army’s topographical engineer, to reconnoiter the Federal position on October 17. They were soon joined by Major Robert Hunter, Gordon’s chief of staff. The little party climbed up Massanutten Mountain where they could see for miles in every direction. They got a good look at Sheridan’s army with their field glasses. They could see “every piece of artillery, every wagon and tent and supporting line of troops,” Gordon wrote.

The Union troops had spread their camps and field works between Cedar Creek and Middletown. Cedar Creek was “a good place for water, but a bad place for a fight,” wrote James Ewer of the 3rd Massachusetts Cavalry. The creek itself, with its torturous curves and steep banks, flowed into the North Fork of the Shenandoah River. There were about a dozen fords across the river and a bridge where the Valley Pike crossed it.

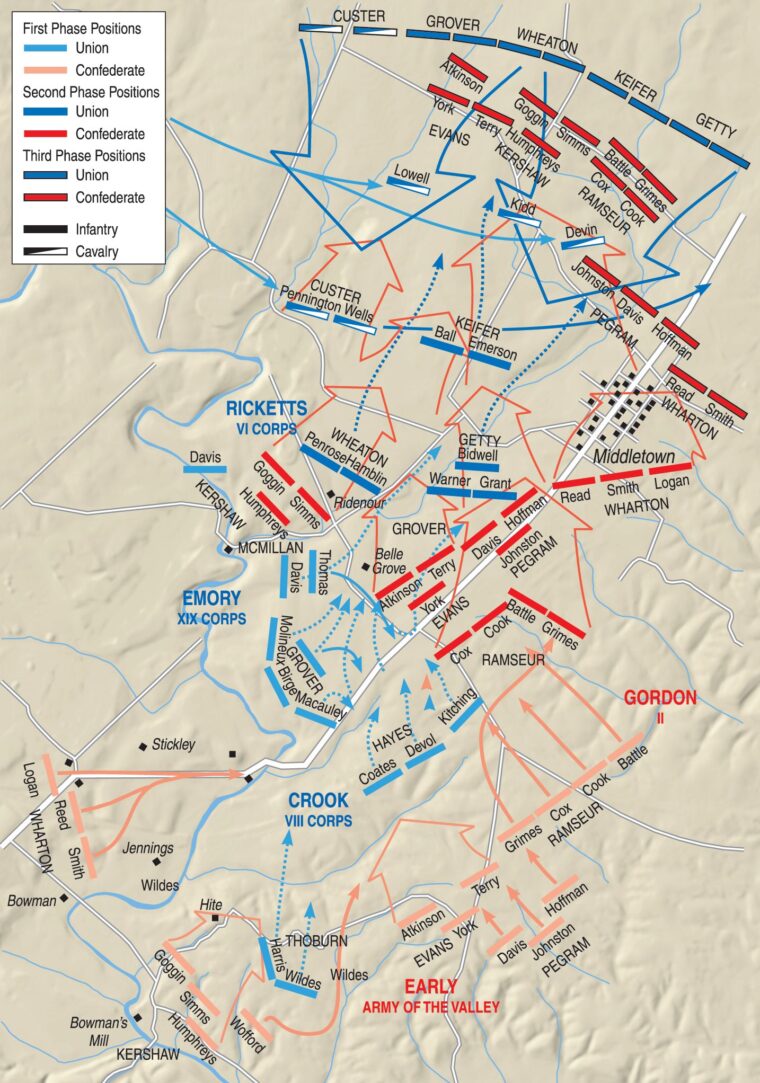

The entrenched VIII Corps held the Federal left north of the creek. The XIX Corps deployed to their right in the middle. The VI Corps held the Federal right near Belle Grove plantation. The cavalry divisions of Custer and Merritt took up positions supporting the Federal right.

Scanning the Federal position, Gordon observed that the Union army had failed to anchor its left flank against any natural feature of the landscape. Upon returning to Early, Gordon insisted that Early attack the Federal left. Early agreed, but first he would have to find a way to get troops through the rough terrain and across the Shenandoah River.

Working together, Gordon, Hotchkiss, and Maj. Gen. Stephen Dodson Ramseur found a narrow rugged trail on October 18 that could be used to attack the Federal left. Early gave his approval and plans were made for an advance to battle. Early gave Gordon command of the Confederate right wing consisting of Gordon’s Division, Brig. Gen. John Pegram’s Division and Ramseur’s Division.

Each man received 60 rounds of ammunition. The troops also received orders to leave behind any unnecessary accessories, such as canteens and tin cups, which might make noise that would alert enemy pickets of their advance. Gordon’s command moved out at 8 p.m. Through the cold dark night “the long gray line like a great serpent glided noiselessly along the dim pathway” wrote Gordon. After a rugged journey southeastward from Fisher’s Hill, Gordon’s troops reached a ford across the Shenandoah River before dawn. Only a mile from the Federal left, they waited for the order to attack, watching the mounted Federal pickets a short distance away.

Also slipping through the darkness toward the sleeping Federal army as part of the Confederate plan were the soldiers of Kershaw’s Division. “We got in sight of the enemy’s fire at 3:30 a.m.,” wrote Early, who accompanied Kershaw on the advance. They waited for another hour before crossing Cedar Creek at Bowman’s Ford.

One mile west of Kershaw, Brigadier General Gabriel Wharton’s division on Hupp’s Hill prepared to advance northeast up the Valley Pike against the Federal XIX Corps. A mile and half behind Wharton, 40 limbered guns stood ready to move out under Colonel Thomas Carter. Five miles north of Wharton, Rosser’s 2,000 mounted and dismounted troopers prepared to make a diversion against the Union cavalry.

As the time neared for the attack, Gordon ordered 300 troopers under Colonel William Payne to ride across the Shenandoah River and disperse the enemy pickets. The sound of gunfire pierced the early morning as the Federal pickets raced back to their camps. Simms’ Brigade soon on the move as well to drive off enemy pickets. On the Confederate left, Rosser’s troopers also moved forward. Early’s army, which was outnumbered two to one by Sheridan’s army, unleashed its attack at 5 a.m.

Captain Frederick Wilkie commanding the 5th New York Heavy Artillery had been uneasy in the early hours of October 19 as he and his men could hear noise coming from east of where they were posted. A handful of other Union officers feared the enemy was up to something, but the senior commanders of the Army of the Shenandoah seemed far less concerned. For the last few days the Federal army had been getting up at 2 a.m. and standing to arms, but Wright canceled that order effective as of the morning of October 19. It would prove to be a costly mistake, for Kershaw’s Division quickly overran Thoburn’s Division.

At the same time, Wharton launched his attack down the Valley Pike toward Cedar Creek. Elsewhere, Rosser launched his diversionary attack securing a ford over the creek and a mill. Rosser’s troopers quickly encountered the 7th Michigan Cavalry, which was soon reinforced by the rest of Colonel James H. Kidd’s Brigade. As for the rest of the Union cavalry, it remained in place awaiting further orders.

On the Federal left, Colonel Rutherford Hayes, the commander of the Second Division of Crook’s VIII Corps, having learned of the disaster overtaking Thoburn less than a mile south of him, formed his division on the east side of the Valley Pike facing southeast. Hayes stretched his left flank to make contact with the raw recruits of the Provisional Division under Colonel Howard Kitching, which had been attached to Crook’s corps.

Colonel Thomas Wildes, the commander of the First Brigade in Thoburn’s Division, was falling back with two Ohio regiments, the 116th and 123rd, when he encountered Emory. With the Confederates 300 yards off in a wooded tract, Emory ordered Wildes to charge the Confederates to buy time allowing Emory to plug the gap between the XIX Corps and Hayes’s position.

Wildes led his Buckeyes, along with Wright who was at that location, into the woods that were full of Confederates accompanied by Wright. “We met with a terrible fire and a counter-charge from ten times our number, which swept us back again to the pike,” wrote Wildes. The Ohioans fell back toward the Federal lines with a bloodied Wright, who had been wounded in the face.

By this time Colonel Stephen Thomas was attempting to fill the gap with his brigade between Emory’s XIX Corps and Hayes’ command, but it was too late. Through the fog that continued to blanket the battlefield, Hayes’ men quickly began to take fire in their left flank from Gordon’s advancing divisions. “Our division had not more than got into line when a most deadly fire was being poured into our ranks and a general confusion prevailed,” wrote Colonel Benjamin Coates, one of Hayes’ brigade commanders. The situation was indeed becoming chaotic as the retreating bluecoats of Thoburn’s battered division came tumbling back through the lines. The Confederates continued to pour a deadly fire into the Federals and Kitching’s men began to give way, soon followed by Hayes’ troops. The future president Hayes had a horse shot out from beneath him and escaped capture by taking cover in a grove of trees.

In less than half an hour, Early’s Confederates had succeeded in shattering Crook’s Corps. With Hayes’ men in retreat, XIX Corps faced the seemingly unstoppable Confederates. As the 40 Confederate guns hammered away at the Federals sheltering behind their earthworks, Wharton, Kershaw and Gordon’s divisions moved toward the Federals.

Emory ordered Thomas to make a hopeless attack against the Confederates with his lone brigade. A hail of lead greeted them as the beleaguered brigade moved forward and were soon overrun by the Confederates. “Men seemed more like demons than human beings, as they struck fiercely at each other with clubbed muskets and bayonets,” wrote Herbert Hill of the 8th Vermont of the vicious fighting. With half the brigade down, Thomas’ men fell back 200 yards and rallied. They made a brief stand, but were soon reeling northward again.

As the Confederates continued to push onward, Gordon’s troops were so extended they were advancing on the XIX Corps’ left and rear. Emory quickly ordered his remaining command to take cover on the reverse side of their entrenchments allowing them to face north and the Confederate attack. At the same time the 176th and 154th New York attempted to refuse the XIX Corps’ left flank. Bolstered by Battery D, 1st Rhode Island Artillery, Emory’s command only hoped to slow the Confederate’s advance allowing the VI Corps to better secure their position.

A heavy fog continued to cover the battlefield as Kershaw came crashing into the Federal’s left flank. “A desperate hand-to-hand fight ensued,” recalled Lt. Col. Alfred Neafie of the 156th New York. He added, “The enemy had planted their colors on our works and were fighting desperately across them meeting with a stubborn resistance, while they swarmed like bees round the battery on our left and rear.”

Attacked from different directions, the situation quickly became critical for the XIX Corps and Emory ordered a withdrawal. “It was now time for us to back out of our hole,” wrote Captain John DeForest of Emory’s staff, “and we marched rearward sadly diminished in numbers, though not a regiment had entirely disbanded.”

As the XIX Corps retreated past Belle Grove, Crook and Emory with a makeshift line of 1,500 troops, many of them officers, attempted to stall the Confederate advance. “We checked the advance of the enemy, and pushed him back a short distance,” recalled Wildes. “We were fighting Kershaw and Wharton’s Confederate divisions,” he added. Crook’s line held for 30 minutes giving time for the wagon supply trains to rumble out of harm’s way.

The VI Corps, which was temporarily commanded by Brig. Gen. James Rickett, was ordered by Wright to dispatch Brig. Gen. Frank Wheaton’s 1st Division and the 3rd Division under Colonel J. Warren Keifer to aid Crook and Emory. As they were greeted by fleeing soldiers, the divisions soon took up position on high ground overlooking Meadow Brooks. They came under Confederate attack and managed to drive them back briefly. Gordon’s divisions and Kershaw resumed their bloody attack forcing the bluecoats of the two Federal divisions to scramble back through Middletown.

The VI Corps remaining division under Brig. Gen. George Getty was posted in front of Middletown, but had been ordered to link up with Wheaton’s Division. As this division was routed, Getty’s 2nd Division stood alone. Getty quickly ordered his division to take up position on a ridge west of Middletown. Here they endured repeated attacks by Pegram, Wharton and Ramseur’s troops. Early brought in his guns and ordered them to hammer the Federals. For 30 minutes the Confederate guns blazed away as the bluecoats hugged the ground. When the guns finally fell silent the Confederates attacked again, driving back the Federal skirmishers.

By this time Getty had received news he was to take command of the VI Corps as Ricketts had earlier been wounded. In turn Brig. Gen. Lewis Grant took command of the 2nd Division. With the Confederates moving in for another assault, Getty realized the tattered division could not withstand another attack. He ordered them to fall back north of Middletown where much of the battered Army of the Shenandoah clustered. Here a new makeshift line was attempting to be formed by Wright.

Merritt arrived with his cavalrymen and Wright ordered him to halt the fleeing Federals. “It being necessary in several instances to fire on the crowds retiring, and to use the saber frequently,” recalled Brig. Gen. Thomas Devin, who commanded the second brigade of Merritt’s cavalry division.

Early’s men pushed into Middletown at 10 a.m. where they collided with Merritt’s troopers, who were supported by five Federal batteries. Early then made the fateful decisions to halt his army’s advance. By this point his ranks were worn out and had dwindled not only to casualties, but to a good number of men who were plundering the Federal camp. Captain D. Augustus Dickert of the 3rd South Carolina recalled that food, blankets, overcoats, hats, boots and shoes lying about “looked to the half-fed, half-clothed Confederates like the wealth of the Indies.”

Early told Gordon “this is glory enough for one day,” but Gordon wanted Early to strike another blow to ensure that there would not be left a single organized company of infantry in Sheridan’s army. “No use in that; they will all go too, directly,” Early replied.

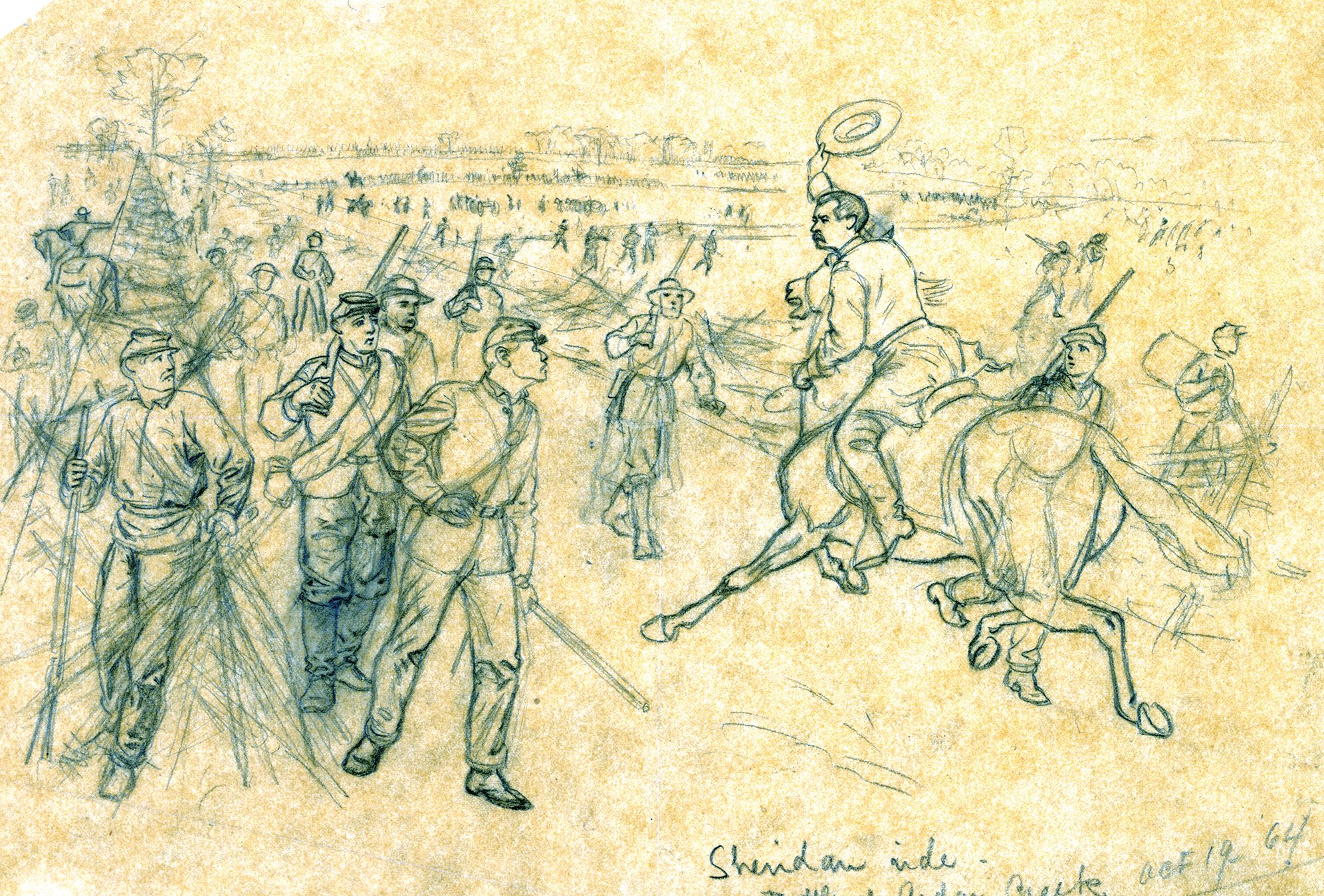

With his Army of the Shenandoah on the verge of collapse, Sheridan was in Winchester where he had arrived on the evening of October 18. At sunrise the following day Sheridan was awakened and informed by an officer on the picket line that artillery fire was heard in the distance. As the fire seemed irregular Sheridan was not concerned, believing it was a Federal reconnaissance he knew was to take place that day.

Sheridan, though, began to grow restless and got up and had breakfast. After again being informed of firing in the distance, he decided to mount up and ride out for Middletown to investigate. He was joined by his staff and a cavalry escort. Two miles south of Winchester on a high ridge, Sheridan spotted wagons in the distance that seemed disorganized and in great confusion. News soon reached Sheridan that his army had been defeated and was being driven north.

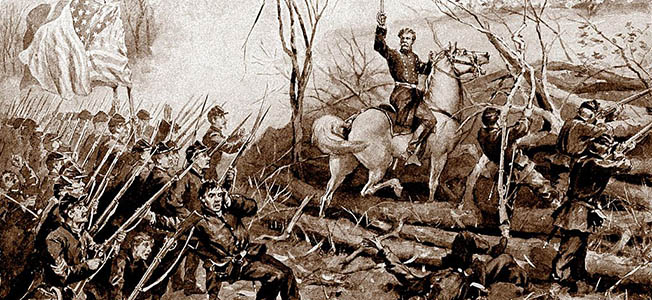

Sheridan rode rapidly south along the Valley Pike, which was becoming more congested with wagons, ambulances and soldiers. Some of the Federal soldiers were plodding away from the battle, while others were resting along the road or boiling coffee. As Sheridan rode by he waved his hat at the men and pointed to the front. When he arrived at the beleaguered Federal lines around 10:30 am he quickly met with Wright. Sheridan was determined to reorganize his battered army and fight. Word soon spread among the troops that Sheridan was back and their morale rose. “Sheridan immediately instilled new vigor, energy and determination into the men,” wrote Lieutenant Edward Duff of the 159th New York. “He passed along the whole line amid the most marked enthusiasm, telling the men they would quarter in their old camp again that night.”

As Sheridan was re-forming his army, skirmishers from Gordon’s Division probed the Union right held by Emory’s XIX Corps at 1 p.m. They met with fierce resistance and Gordon did not push the attack. Sheridan, on the other hand, was ready to launch an attack; but first he wanted to determine Longstreet’s whereabouts. Although he first thought the supposed Longstreet message a ruse, Sheridan wanted to be sure. At 4 p.m., satisfied that just Kershaw’s Division of Longstreet’s Corps was present, he ordered a counterattack.

“It was a glorious sight to see that magnificent line sweeping onward in the charge,” wrote Colonel James Kidd, a brigade commander in Merritt’s Cavalry Division. Sheridan’s line stretched for two miles. From right to left were Custer’s Cavalry Division, the XIX Corps, the VI Corps, and Merritt’s Cavalry Division. Crook’s battered troops, meanwhile, formed up to the rear and left of the VI Corps.

As the Federals moved forward Confederate guns opened up. Facing the two Union corps was Gordon’s Division on the Confederate left, while to their right was Kershaw and Ramseur’s Divisions. To the right and rear of Ramseur was Pegram’s Division with Wharton on their right, positioned on the east side of the Valley Pike.

Merritt’s troopers moved ahead of the slower infantry and soon took vicious fire forcing them back to reform. The VI Corps fared little better. Covered by a stone wall, Ramseur’s Division blazed away at the Federal infantry opposite them. A good part of the corps reeled back under the Confederate rifle and cannon fire. Only the Vermont Brigade and much of Colonel James Warner’s Brigade of the 2nd Division held their ground and traded volleys with the graybacks behind the stone walls.

Meanwhile on the Federal right, Custer had spotted Rosser’s Cavalry Division lurking nearby. Custer was compelled, he later reported, “to break my connection with the infantry on my left, in order to direct my efforts against the force of the enemy approaching my right.” A battery quickly opened up on the Confederate horsemen and Custer dispatched Colonel Alexander Pennington to attack them vigorously.

The XIX Corps’ right flank was exposed and they came under deadly fire from Gordon’s Division. However, Gordon had problems as a gap existed between Brig. Gen. C.A. Evans’ Brigade which held the extreme left of his position and the rest of the division. Brig. Gen. James McMillan’s Brigade and part of Colonel Edwin Davis’ Brigade of the XIX’s Corps 1st Division wheeled to the right to confront this deadly fire. The bluecoats returned fire and charged, scattering Evans’ Brigade who fled to the rear.

“You are doing splendidly, but don’t be in too much haste,” Sheridan warned the soldiers of the XIX Corps. “Now lie down right where you are, and wait until you see General Custer come down over those hills,” ordered Sheridan, adding that once the cavalry arrived they were to “push the Confederates.” The hunkering bluecoats would not have long to wait as Custer’s troopers soon came thundering in from the west.

The soldiers of the XIX Corps attacked anew. Their assault proved too much for Gordon, who wrote that Sheridan’s counterattack had rolled up his left flank “like a scroll.”

“The suddenness of our onset made resistance impossible, and they fled before us, thus exposing the flank of the main line, upon which we now poured down with a still fiercer shout,” wrote Captain Orton Clark of the 116th New York.

The VI Corps and Merritt, meanwhile, had renewed their assaults. Kershaw’s men fought desperately until someone shouted that Federal cavalry were surrounding them. “In a moment our whole line was in one wild confusion, like pandemonium broke loose,” wrote Dickert.

The Confederate soldiers belonging to generals Wharton and Pegram who had held out against Merritt’s horsemen and Federal guns, eventually fell back on the Confederate right. Ramseur, though, resolved to continue fighting as Federal troops advanced against his division. When Ramseur received a mortal wound, his position collapsed.

By 5:30 p.m. the Confederates were in a full rout. The defeated graybacks splashed back across Cedar Creek. Early’s troops tried one last time to make a stand, but the Federals prevailed. While the Federal infantry stopped their pursuit at the creek, the cavalry continued to gallop after Early battered and worn troops. A bridge over a stream near Strasburg became blocked by a couple of wagons creating a bottleneck. Federal troopers soon came upon the traffic jam finding artillery, wagons and ambulances filled with wounded all abandoned.

At Fisher’s Hill the cavalry reined up their tired horses, ending the pursuit. The Federal victory had been costly as they lost 569 men killed, 3,425 wounded and 1,770 missing or captured. The butcher’s bill for the Confederates, on the other hand, amounted to 1,860 killed or wounded and 1,200 captured.

As the Confederate trudged onward in the early hours of the 20th to put more distance between them and the victorious Bluecoats, Dickert noticed General Early “sitting on his horse by the roadside, viewing the motley crew as it passed by. He looked sour and haggard. You could see by the expression of his face the great weight upon his mind, the deep disappointment, his unspoken disappointment.”

Disappointment indeed, what had been a promising start at Cedar Creek, with victory in his grasp, Early had not only lost the battle, but the Shenandoah Valley to the Federals. Lincoln had another victory to campaign on in the coming presidential election.

This essay suceeded on being highly accurate on details, with an extraordinary description of the facts related to this epic moment in American Civil War with a narrative that is profoundly deepened on the significance of the deciseveness of an powerfull lidership in moments of hardship. Sheridan was the absolute most effective fighting-general in the American Civil War, a conflict Marked by several brilliant leaders.