By Arnold Blumberg

The United States Army came late to the idea of employing airborne troops in time of war. The first U.S military man to see the potential of such a force and then formally propose the concept was Brig. Gen. William “Billy” L. Mitchell. In October 1918, Mitchell suggested the creation of an American airborne component to Gen. John J. “Black Jack” Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force fighting in France against Imperial Germany.

A maverick and outspoken proponent of airpower, Mitchell posited that as part of any Allied general offensive which might take place in 1919 one U.S. Army infantry division (at the time each contained 28,000 men, 17,000 of which served as combat troops) should be employed as an airborne unit.

“We should arm the men with a great number of machine guns and train them to go over the front in our large airplanes which would carry ten or fifteen of these soldiers,” he explained. “We would equip each man with a parachute, so that when we desired to make a rear attack on the enemy, we could carry these men over the lines and drop them off in parachutes behind the German position.”

Mitchell outlined the tactics the paratroopers would use once they dropped to the ground: “They could assemble at a prearranged strong point; fortify it and we could supply them by aircraft with food and ammunition” and then, supported by friendly airpower, “we could attack the Germans from the rear, aided by an attack from our army on the front.”

But World War I ended before the general could carry out his plan, and the idea of creating an American parachute division disappeared as the U.S. Army rapidly demobilized.

During the interwar period, interest in airborne capacity was almost non-existent. When the U.S. military conducted an early parachute troop experiment—12 Marines over Washington, D.C.—it was downplayed as a “carnival attraction” by the Marine Corps brass. In 1926 the Army dropped three soldiers and a machine gun from four two-man observation planes at Brooks Field, Texas, and did not conduct a second drop until 1940.

The U.S. military also had little interest in gliders, despite a robust national civilian gliding program. In 1922, the Army Air Corps briefly considered gliders as aerial targets. The Navy began training glider pilots in 1933, but dropped the program after three years due to an already sparse interwar budget.

The U.S. Army’s main interests in gliders during the interwar period was for moving troops and equipment by aircraft from point to point. The use of gliders, paratroopers, and air-landed forces in combat wouldn’t be fully explored until events overseas prompted serious attention to the matter.

After the Nazis came to power in 1933, a wide range of programs were put in place to train future German aviators by supporting civilian glider clubs. Beyond this, gliders were turned into weapons of war with the creation in 1939 of the DFS-230, a 37.5-foot glider that weighed 1,800 pounds, with a wingspan of 72 feet. It could transport a pilot and nine combat equipped soldiers or 2,800 pounds of equipment towed by a Junkers Ju-52 transport plane. The DFS-230 became Germany’s primary military glider during World War II.

In the meantime, the Soviet Red Army was theorizing about airborne warfare. In 1931, a 164-man parachute experimental unit was formed. By 1932, the Soviets had performed 550 airborne exercises, and the next year they had formed 29 parachute battalions. According to regulations promulgated in 1936, the Red Army stated, “Parachute landing units are the effective Means …[of] disorganizing the command and rear services structure of the enemy.” Along with its growing parachute force, the Soviet military crafted a glider command manned by 57,000 glider pilots.

Ironically, despite forging a commanding lead in the doctrine and establishing a formidable parachute and glider command, the Soviets never dropped more than a brigade-sized unit at any one time during World War II. In 1943, they abandoned large-scale airborne operations in favor of using their skilled parachute warriors in partisan and diversionary roles.

While most military observers in the U.S. and Western Europe saw “doubtful tactical value” in Soviet airborne progress, Germany had a different take. With the full support of Herman Goering, head of the nascent Luftwaffe, Col. Kurt Student pushed for a robust German glider and parachute force. In 1933 Goering, serving as the Prussian Minister of Police, authorized the formation of a small parachute unit made up of policemen. When he became chief of the Luftwaffe, he promoted Student and made him commander of Germany’s first airborne division. By the end of World War II, Student had raised 11 airborne divisions, two airborne corps, and one airborne army, the latter which he commanded.

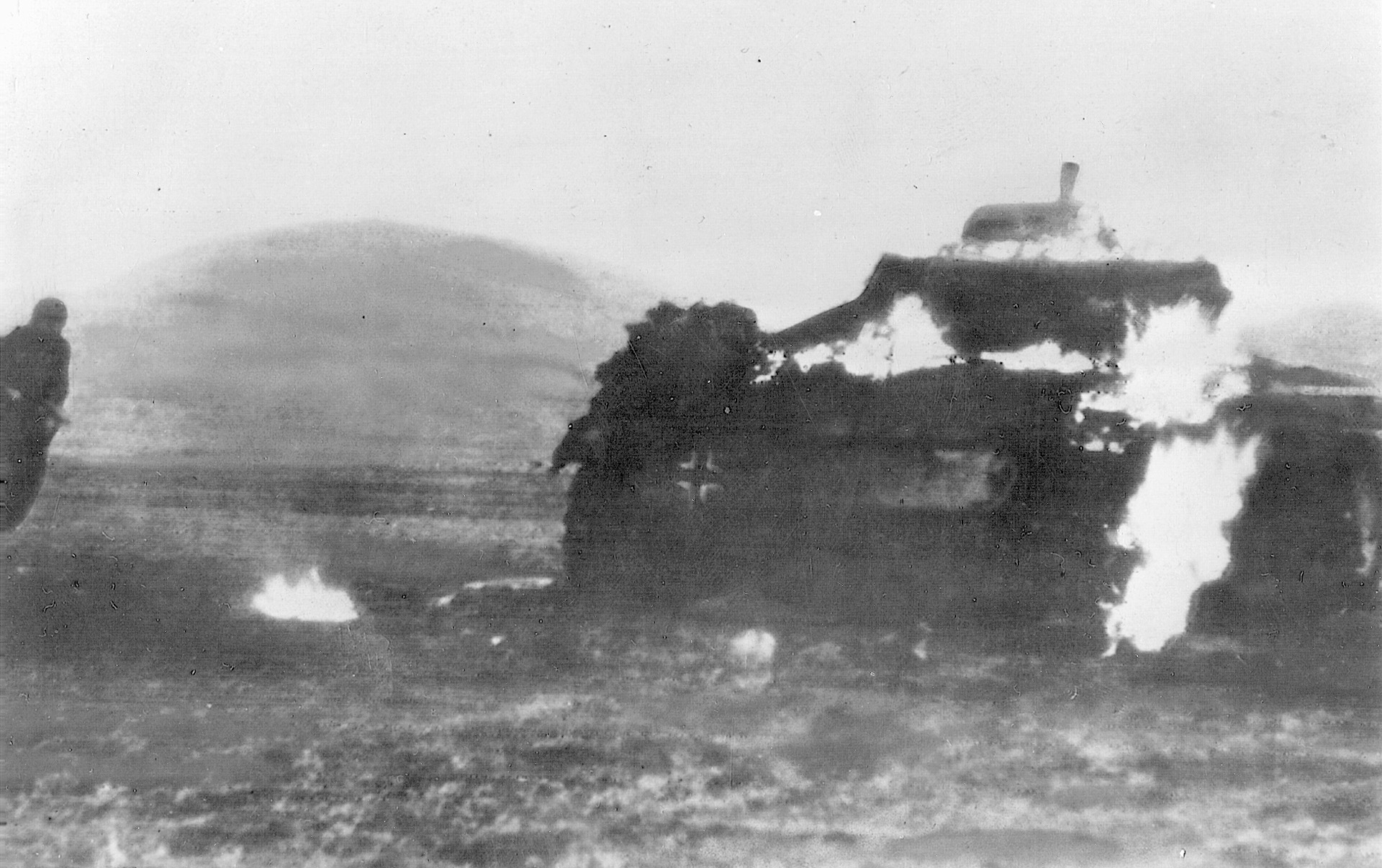

Following the success of German glider and parachute units during the first two years of the war—including the invasions of Denmark and Norway (April 1940), Holland and Belgium (May 1940), and Crete (May 1941)—U.S. airborne supporters began pressing for similar capability. The conquest of Crete solely by glider and parachute troops was “the greatest single impetus to airborne development and expansion” in the U.S. Army. Lt. Col. Jack C. Cornett, an instructor at the U.S. Army’s Command and General Staff College, wrote that the invasion of Crete was a “definite shock to many who had scoffed at this new weapon. It was startling…. It was thought-compelling. It was new…. And most important of all, it was successful!”

Unknown to the U.S., German airborne forces had suffered heavy losses in “Operation Mercury,” the invasion of Crete. So much so that Hitler forbade further large-scale airborne operations for the duration of World War II.

Immediately, American military airborne enthusiasts, like future General James M. Gavin, started studying German tactics, especially the “German method of organizing after landing, the equipment used in the assault and follow-up, and their means of control and command.”

Another early student of airborne warfare was General William C. Lee, who came to be known as “the father of American paratroopers.” Lee published several papers in early 1941 stressing the importance of forming this new arm of the military.

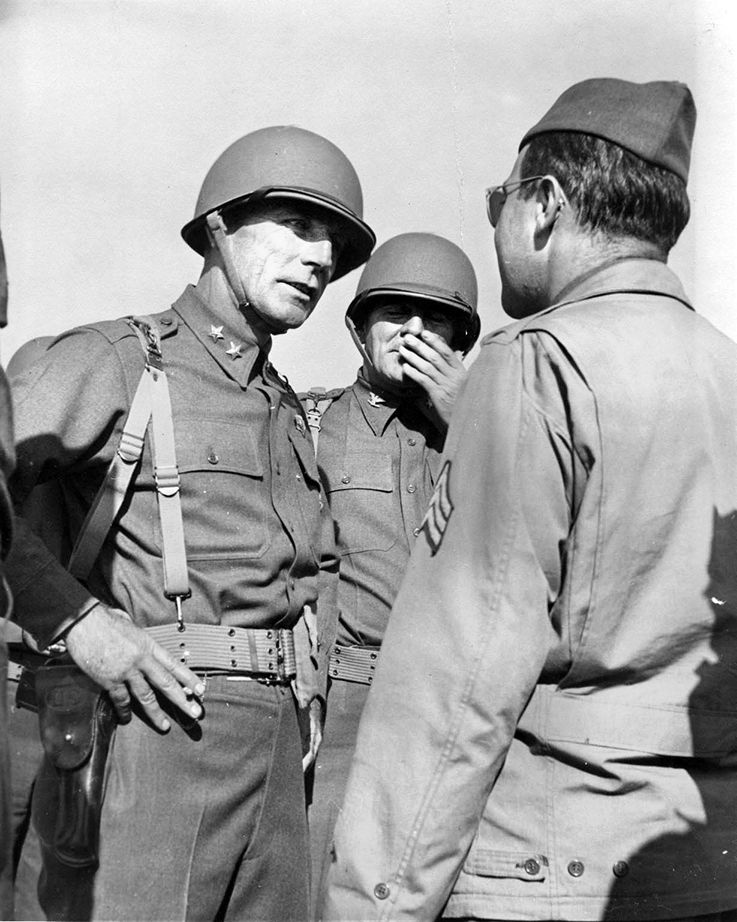

Lee, Gavin, and others argued that merely copying the German airborne forces model would never be enough to assure victory. Understanding that the U.S. was far behind, they demanded a “quantum jump on the Germans.” By war’s end, through the efforts of Lee, Gavin, and Generals Matthew B. Ridgeway and Maxwell D. Taylor, the U.S. Army fielded five parachute divisions (11th, 13th, 17th 82nd and 101st), as well as several separate airborne regiments and battalions.

The first step toward a permanent U.S. Army airborne came in May 1939, when the War Department authorized a small outfit that could be “…transported by airplanes, to parachute to the ground a small detachment to seize a small but vitally important area, primarily an airfield, upon which additional troops will later be landed by transport aircraft.” The resulting study came up with four scenarios for the use of airborne formations: (1) drop within enemy territory to destroy opposing communication and industrial sites; (2) use for reconnaissance missions; (3) drop battalion or regiment size units to occupy key points behind enemy lines; and (4) work in conjunction with friendly mobile forces at far distances from the main body of friendly forces.

Nothing came out of the study for eight months until Lee, a World War I veteran and Regular U.S. Army officer, was tasked with breathing life into the airborne project. He first had to determine which command section—Engineers Corps, Air Service, or Infantry—would control a fledgling airborne force. Infantry was ultimately chosen in August 1940. To assist, Lee took on board then-Captain Gavin, a young combat veteran, who like many flocking to the paratroopers was tough, adventurous, and spread the novel idea that airborne warriors had to be able to think for themselves since they would be fighting isolated and in small groups, sometimes without officer guidance.

In April 1940, a parachute test platoon was formed from the 29 Infantry Regiment based at Fort Benning, Georgia. Its platoon leader was Lt. William T. Ryder. The unit was made up of two officers and 48 enlisted men, all volunteers, seasoned soldiers and all in very good physical condition. An eight-week training program was established, based on that of the U.S. Army Rangers and British Commandos. This model was used as parachute troops, in theory, were to be used only in small numbers against high-risk targets. Physical training, night fighting, use of explosives, and hand-to-hand combat were stressed. The training regiment was then to be used at its conclusion to help determine airborne tactics, equipment, and uniforms.

The platoon’s first jump occurred on August 16, 1940. It was viewed by Gen. George C. Marshall, U.S. Army Chief of Staff, who was so impressed with the demonstration that he ordered the formation of the 1st Parachute Battalion (later renamed the 501st Parachute Infantry Battalion) on September 16, 1940. In November of that year the battalion was assembled at Fort Benning. The unit was swamped with volunteers, and the subsequent training resembled that of Rangers or Special Forces since it was still assumed the parachute troops would remain as small commando-type units.

In March 1941, a new organization designed to train, organize, and create tactics for the rapidly expanding U.S. Army airborne effort was established at Fort Benning. The Provisional Parachute Group enhanced the already tough physical training and mental fitness regime already established. Three new parachute battalions, the 502nd, 503rd, and 504th, were formed by October 1941.

As American airborne forces developed, the means to deliver soldiers and equipment by glider moved apace. In February 1941, the concept had been batted around in the circles of the U.S. Army Air Corps. By December 1942, a total of 6,000 glider pilots had been trained. Most were trained on the CG-4A Waco constructed of wood, steel tubing, and canvas. It had a wingspan of 83.6 feet, was 48 feet long, and had a cargo capacity of 4,060 pounds. In addition to a pilot and co-pilot, it could carry either 13 combat soldiers, a jeep, a trailer, or one small artillery piece. More than 14,000 Wacos were built during the war.

By the spring of 1942, the leaders forming the American airborne force realized that in order to make a real impact on any battlefield, the disparate parachute and glider units had to be combined into larger formations. The German assault on Crete and the force used by them confirmed the American premise. So, in mid-1942, Lee and Gavin traveled to Washington, D.C., with the idea that an entire parachute division must be created. With their urging and, with the German example of the successful use of airborne troops clear, the U.S. 82nd Infantry Division, which had seen service in France during World War I, was reactivated on March 25, 1942, and on August 15 of that year designated the U.S. Army’s 82nd Airborne Division under the command of Major General Ridgeway. Its initial cadre consisted of 700 officers and 1,200 enlisted men from the 9th Infantry Division stationed at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

The 82nd, nicknamed the All-American Division in World War I, since it contained men from all the states of the Union, would take part in every airborne operation initiated by the U.S. Army in Sicily, Italy, and Northwest Europe. Through its actions, it would serve as the laboratory in which the American airborne tactics, organization, weapons, and leadership would be developed throughout the war, as well as to this day.

Author Arnold Blumberg is an attorney with the Maryland state government and resides with his wife in Baltimore County, Maryland.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments