By Robert Barr Smith

The two regiments from the county of Kent, down in southeastern England, are of both ancient and honorable lineage. Today, army reorganization has made them a single unit, along with the Royal Hampshires, but traditionally there has been more than a little rivalry between them, as one would expect between Men of Kent and Kentish Men.

The regiment’s old name, the Queen’s Own Royal West Kent Regiment, has never been so famous as its East Kent counterpart. The East Kents were called the Buffs, from the buff facings on their uniforms in the old days of scarlet coats. “Steady the Buffs!” calls up thrilling and romantic visions of a thin red streak tipped with steel.

On the other hand, who’s ever heard of the Dirty Half-Hundred?

“Dirty Half-Hundred”: A First-Class Regiment

The Queen’s Own West Kent Regiment began life as the 50th Regiment of Foot, and there has been a 50th Foot at least as far back as 1741, maybe earlier. At times the regiment had served at sea as marines, which accounts for the quaint custom of “piping the men to dinner,” retained throughout the regiment’s long life. Its connection with its recruiting grounds—West Kent and South London—dates from 1782.

The regiment got its less than romantic nickname during the Peninsular fighting against Napoleon in 1807-1808, specifically at the Battle of Salamanca, when the poorly dyed black facings on its uniforms ran in the rain. The result was a markedly unmilitary mess, particularly since, as the soldiers wiped sweat and rain from their faces, the black dye was transferred to their skin as well as the red cloth of their coats. When they later became “The Queen’s Own,” royal patronage entitled the regiment to change the black uniform facings to royal blue, a decidedly good thing.

In spite of their nickname, however, the West Kents were always a first-class regiment. During World War II, the Japanese in Burma, particularly those who did not leave their bones in the dreadful hills of Nagaland, had painful reason to remember the West Kents. In 1944, an entire Japanese division broke its teeth on a tiny British garrison in a pleasant hill station called Kohima. That garrison was anchored by a battalion of the Dirty Half-Hundred.

“Perfectly Bloody” Burma

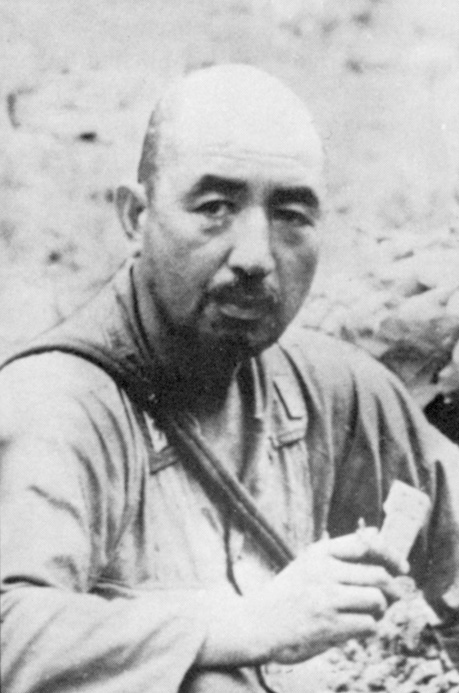

The fighting there was as ferocious as any in all of World War II. A Japanese colonel, Kuniji Kato, quite accurately called the Kohima fighting “that great, bitter battle,” for that is precisely what it was. At this insignificant place the Japanese would hurl three infantry regiments at the Fourth Battalion of the Dirty Half-Hundred and a handful of other British soldiers of several different races. Thousands of Japanese left their bones at Kohima, but Kohima held.

There never was a good place to fight a war. However, of all the nasty parts of the earth in which men have tried to kill each other, Burma is by all odds the worst, and the border hill country between Burma and India is no better. “Perfectly bloody,” one British officer called Burma, “Gorges, cliffs, mountains, and dense forest, much of it spiny bamboo, whose spines, sharp as needles and hard as steel, are three to ten inches long.” Six-foot stands of sharp-edged Kunai grass blocked movement, thorns and vines dragged at men’s clothing, equipment, and flesh. Thick stands of bamboo had to be chopped out, both at ground level and just below their tangled leaves, to create a sort of tunnel for moving troops.

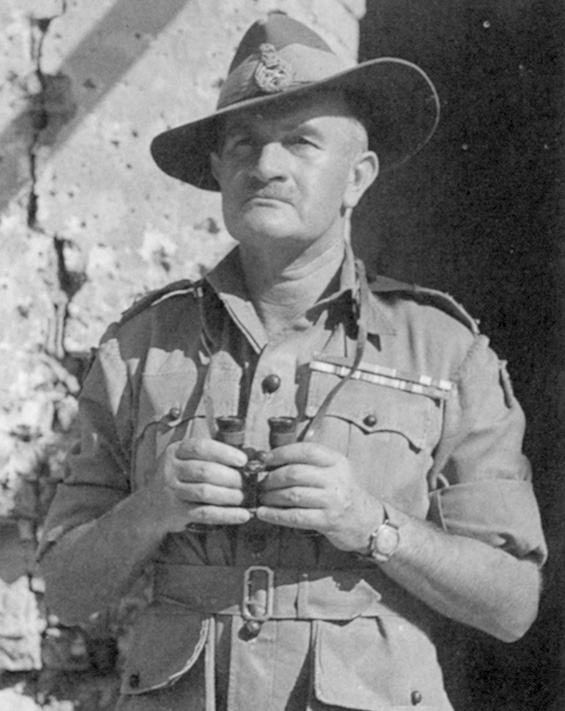

General William Slim, a very tough officer, called the border area “those hellish jungle mountains.” Those hellish mountains were infested with malaria, typhus, cholera, dysentery, yaws, and dengue fever, and they crawled with hungry insect life. In addition to huge, insatiable mosquitoes, sandflies, and ticks, there were the leeches, which, if you pulled them off and left the head behind, produced the Naga sore. This was a monstrous, putrifying ulcer five or six inches wide, eating into the flesh and muscle. It could kill a man who did not get medical attention.

Swift and wide rivers, difficult at the best of times, turned to muddy torrents in the long months of the monsoon season. Troops and pack animals struggled up jungle-covered knife-edged ridges over paths slimy and slick after hundreds of inches of rain. Radio communication was sporadic and temperamental, a fact not always appreciated by base personnel. One officer, trying to replace a failed radio, was told to “experiment with the length, direction and position of your aerial.” The officer replied with some exasperation, “I have experimented with the aerial in every position except one, and that I leave to you.”

Chindits vs Jiffs

As 1944 dawned, Slim, commanding the British 14th Army, was laying plans for an offensive against the Japanese, but the Japanese struck first. The Japanese command was well aware of the vulnerability of its long supply line, the slender railroad running north through Burma, the vital town of Mogaung, and all the way to Myitkyina far to the north. British Chindit units, operating deep behind Japanese lines, had cut the critical railroad repeatedly during the past season, and the Japanese command had been forced to divert substantial troop assets to reopen the line.

General “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell’s army of Chinese was advancing on the Japanese-held town of Myitkyina from the north. The progress of this horde was glacial at the best of times, but the Japanese knew that with the end of the monsoon the Chindits would be back. They would raise unmitigated hell behind the Japanese lines, and this time they might close the vital railroad for good. If that happened, Myitkyina would inevitably fall, and even the almost inert Chinese would then move south into the heart of Burma.

In late June the Chindits of Brigadier Mike Calvert’s 77th Brigade would indeed cut the railroad, first setting up an immovable block at the place nicknamed White City, then taking the critical town of Mogaung from a larger force of Japanese in ferocious fighting. With Mogaung firmly in British hands, the Japanese in Myitkyina were doomed. In February 1944, all of that was in the future, but even now the Japanese Fifteenth Army commander, Lt. Gen. Renya Mutaguchi, could see great trouble coming if he remained on the defensive.

Mutaguchi decided to attack. If he could reach the British supply depots, which he could certainly use, and disrupt British communications, he would stop the expected British dry season offensive before it ever started. He might also open opportunities for the men of the turncoat INA, the so-called Indian National Army, who were attached to his army. With luck he might sweep all the way into eastern India.

Then and later, the INA, called “Jiffs” by the British, proved to be a dull tool. On at least two occasions, thousands of them surrendered without making much of a fight. They were not popular with loyal native troops of the Indian Army. As General Slim later wrote, “Large numbers [of Jiffs] surrendered but our Indian and Gurkha soldiers were not too ready to let them do so, and orders had to be issued to give them a kinder welcome.”

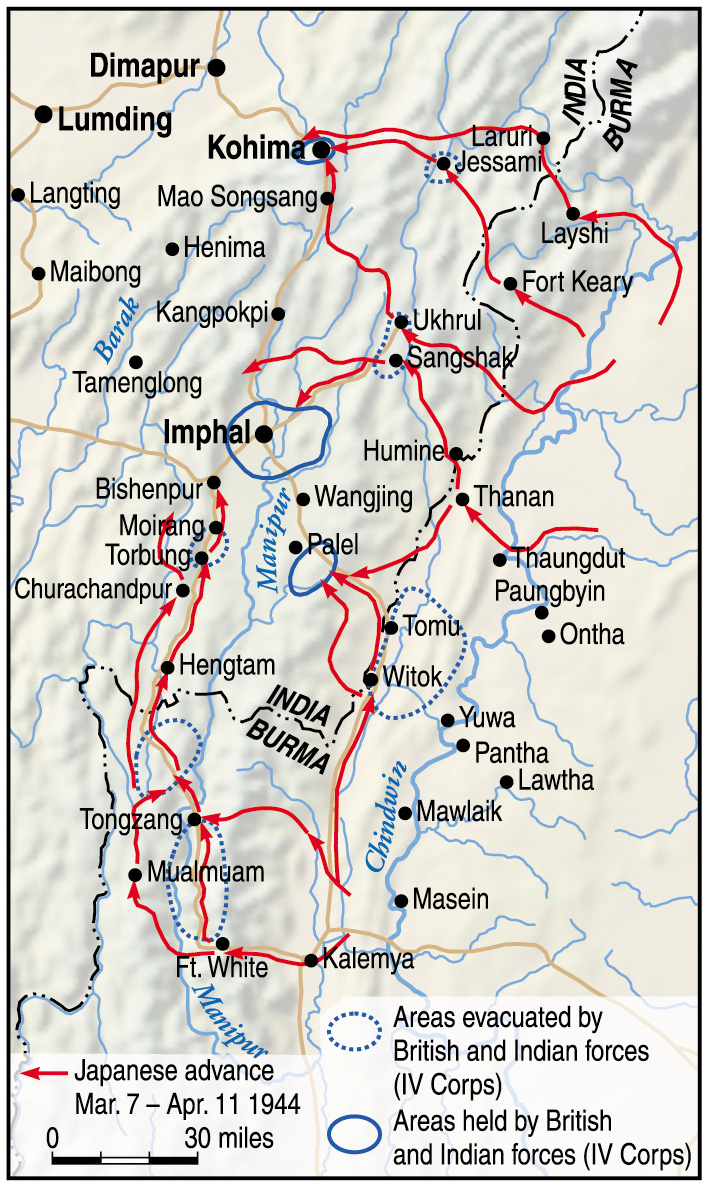

Ha-Go and U-Go: The Two Prongs of the Japanese Offensive

So, in early 1944, at the beginning of the dry season, the Japanese launched a two-pronged offensive. The first prong, called Ha-Go, was launched in February in the south in the Arakan. It foundered on the rock of determined British resistance, in particular around a position known as the Admin Box. There, the 2nd West Yorks and the 6th Dragoons, strengthened by a collection of cooks and drivers and such “odds and sods,” in British Army lingo, stopped a whole Japanese division cold, inflicting 5,000 casualties. Ha-Go did achieve part of its purpose, causing the commitment of some British reserves into the Arakan. However, Ha-Go was only the curtain raiser, only the prologue to the big show, which the Japanese command called U-Go.

U-Go would hurl 100,000 men at Assam, in eastern India, in particular at the areas of Dimapur and Imphal, which lay on the vital railroad line east of India’s Brahmaputra River. The Japanese reasoned that if these critical areas could be overrun, the British 14th Army would have to retreat from the border country, and Japan would control a large slice of eastern India. Perhaps the long-awaited Indian uprising could at last come to pass, and Japan might still triumph on the Asian mainland. Mutaguchi later admitted that he pictured himself riding a white horse triumphantly through the streets of Delhi. Delhi, however, would prove to be a very long way away.

If the Japanese were to achieve the great prize, the blooming rose of eastern India, they would first have to grasp the thorn of the hill station at Kohima, which lay on a saddle between two mountain ridges, some 5,000 feet above sea level. The terraced settlement, perched on a series of little hills, commanded the road between Imphal and Dimapur, about halfway between the two. Mutaguchi would launch no less than the entire 31st Division at this tiny place.

Thanks to an unimaginably clumsy administrative scheme, the British commander on the ground at Kohima, Colonel Hugh Richards, never knew from one day to the next what force he might have to defend this increasingly critical position. Units would appear, begin to dig in, then be ordered away by other headquarters without reference to him. One thing, however, remained virtually certain: The garrison would remain small, whatever its composition, and once the Japanese offensive began, it would soon be encircled.

“Whoever Designed Burma Designed it For the Japanese”

Like Kohima, the major British troop and supply concentrations down on the Imphal plain would have to be supplied by air, for both the Imphal-Dimapur road and the parallel railway ran north and south and would be easy for the Japanese to sever. “Whoever designed Burma,” wrote General Slim, “designed it for the Japanese.”

Nevertheless, the canny British commander had confidence in the ability of the RAF and USAAF to resupply his troops, and the aircrews would not fail him. Slim was not about to engage the major part of his forces in a twilight battle along the terrible jungle-draped limestone ridges to the east. He was, as he put it, “Tired of fighting the Japanese when they had a good line of communication and I had an execrable one. This time I would reverse the procedure.”

Therefore, he elected to fight on the Imphal plain, blocking the only road in the region leading west into India. Here his units had much better observation, there were airstrips and large drop-zones for resupply, and British fighter-bombers and defensive firepower could control the battlefield as, in the event, they did.

Throughout the course of the Japanese assault on Imphal, the British forces there would throw back repeated Japanese attacks. The fighting was fierce, often hand-to-hand, but the issue was never in doubt. While the Japanese cut both the roads north to the depots at Dimapur and west into India, RAF and USAAF transport aircraft flew in prodigious quantities of supplies of all kinds. In addition to 14 million pounds of rations and a million gallons of fuel, the air forces delivered some 12,000 replacements and flew out about 13,000 wounded men.

The steady flow of ammunition and other supplies into Imphal and Kohima was the supreme achievement of British and American transport pilots. Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, British supreme commander for the area, had, without authority, borrowed a number of precious C-47 Dakotas from the transport groups flying supplies over the “Hump” to China. Realizing that the critical decision would be reached at Imphal and Kohima, he now flatly refused to return them, in spite of increasingly strident demands as far up the political ladder as Washington, D.C. With Winston Churchill’s solid backing, Mountbatten kept his airplanes and the supplies kept coming, even in the vile weather of the monsoon.

Air drops at isolated Kohima were particularly difficult because of the tiny space enclosed within the British perimeter. Transport aircraft flew almost suicidally low, trying to make certain at least some of their precious supplies fell where the garrison could reach them. Among their most important drops were vehicle inner-tubes filled with water, a supplement to the pitifully insufficient water supply inside the Kohima perimeter.

Some of the supplies they dropped went in by parachute, while others were free-dropped, as they regularly were to Chindit units far behind the Japanese lines. It was in Burma that the acronym DFF first appeared. It stood for “death by flying fruit,” a reference to at least one fatality from free-dropped supplies.

to difficulty negotiating transportation routes.

Hawker Hurricane fighter-bombers flew close support missions at treetop level, boring in as low as 50 feet with bombs and cannon, attacking Japanese positions marked by smoke rounds from the garrison’s mortars. Even in hideous monsoon conditions the faithful “hurribombers” flew sortie after sortie in support of the ground troops, while Supermarine Spitfires covered the lumbering transport aircraft. Around one of the Imphal airstrips, ground crews watched their pilots striking Japanese artillery, which was shelling the strip.

In spite of the devotion of the aircrews, most of the British and Indian troops fought hungry. The standard meal, morning and evening, was hard biscuits and jam. In the middle of the day there were more hard biscuits, and maybe a single can of bully beef to be shared between four men. With most meals the British managed that staple of the British Army, a cup of tea loaded with canned condensed milk and sugar. In the evening, assuming the unit was not in contact and supplies could get through, there was sometimes a tot of rum.

The Garrison at Kohima

If the issue on the Imphal plain was never really in doubt, that could not be said of the desperate battle for little Kohima. Kohima was a peaceful place at the start of the Japanese offensive. There was a replacement unit there, a hospital, a convalescent area, even something called a “cattle conducting section,” plus various points for the storage and issue of ordinary supplies. The area was not a natural defensive position, but it commanded the vital road. It had no permanent garrison worth mentioning.

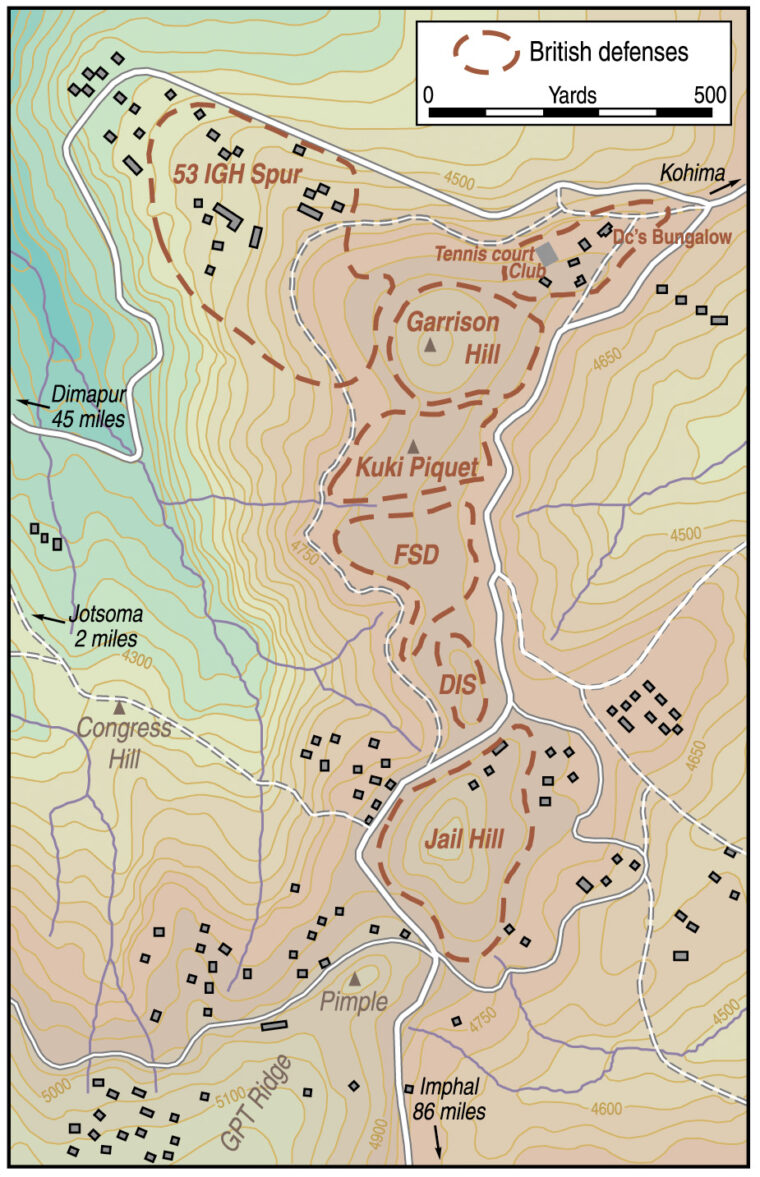

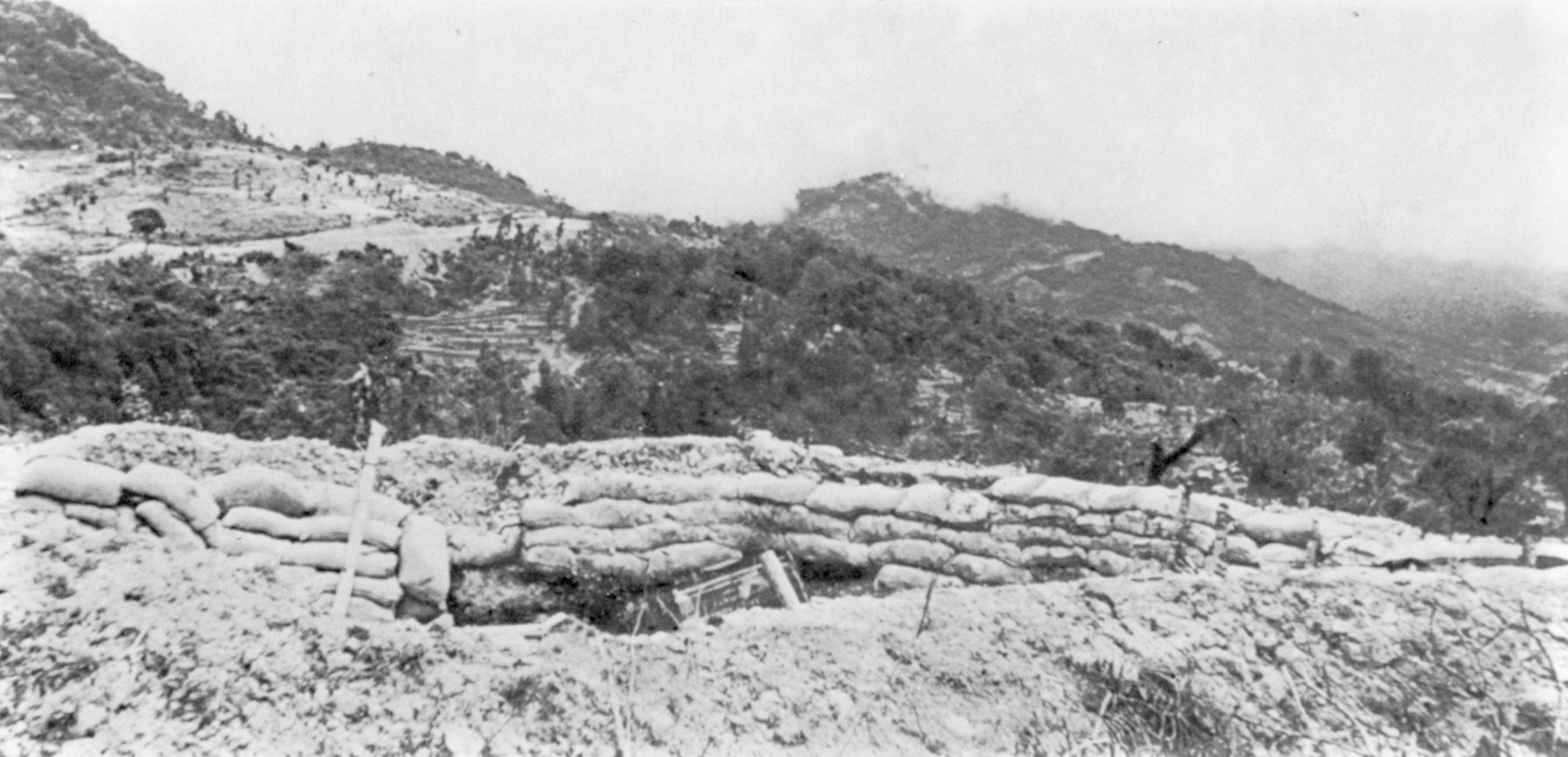

Kohima’s salient features were several small hills: Garrison Hill, Kuki Piquet, and FSD (Field Supply Depot), where there were several large huts full of supplies, bread ovens, and so on. Another little rise was called DIS, where the Daily Issue Store was located. The deputy commissioner’s bungalow—seat of the civil administration—lay at the center of the settlement, and on terraces near it were a tennis court and the British club. All of these little pieces of high ground were valuable defensive positions, but all were overlooked by still higher ground, rugged bush-covered mountains rising as high as 10,000 feet.

For all his intelligence and experience, Slim had made one major error in estimating Japanese intentions. That mistake, which he honestly admitted, was that he had predicted the Japanese would send no more than a regiment against Kohima to cut the Dimapur-Imphal road. As the British prepared the defense of Dimapur, they could not know that the Japanese did not intend to attack that place. Instead, Mutaguchi was committing an entire division of experienced troops to the assault on Kohima’s tiny garrison.

Buying Time For Kohima

The civilian deputy commissioner for the Kohima area was Charles Pawsey, a veteran of 20 years in these hills. The Naga people lived in hilltop villages throughout the surrounding region and had come to regard Pawsey as their friend and father. In return, Pawsey loved, protected, and watched over these tough, cheerful people. This close relationship would bear huge dividends for the British. Throughout the siege and the subsequent fighting at Kohima, the Nagas were a constant source of absolutely reliable intelligence and carried hundreds of British wounded to safety through thick jungle and over slimy, precarious hill tracks.

For the Japanese, resupply was an endless problem, never solved. With the British and Americans controlling the air, there could be no air drops to Japanese units, even had there been transport aircraft available. Allied aircraft hammered the Japanese supply lines. Japanese soldiers’ diaries record terrible tales of murderous Allied air strikes, of the steady waste of men and pack animals on the tracks leading west, and of hundreds of burned-out vehicles littering the roads and ravines.

Lieutenant General Kotuko Sato’s 31st Division, driving for Kohima, was held up for vital days by the stand of small British, Indian, and Gurkha units, including the 50th Indian Parachute Brigade and elements of the Assam Regiment and the Assam Rifles, a paramilitary police formation. The Parachute Brigade, making a major fight at Sangshak, cost the Japanese 58th Regiment half its enlisted strength and two-thirds of its officers before it was overrun and scattered.

Smaller units of the native Assam Regiment and the Assam Rifles fought like veterans. One isolated company of the Assam Rifles fought alone for four days until, menaced by a Japanese battalion, the company’s British commander ordered his men to abandon their position and slip away into the night. The captain stayed behind alone, destroying equipment, and in the next dawn fought singlehanded until the Japanese overran his position and killed him. The sacrifice of these units cost the Japanese heavy casualties and bought enough time for the British command to order the 161st Brigade back up the twisting road toward Kohima.

Repelling the First Attack: V Force and the 161st Brigade

Priceless intelligence was provided the British command by an ad hoc organization called V Force. This shadowy mix of local tribesmen and British civilians (including at least one woman), most of whom worked for the forestry service in happier times, was led by a handful of British officers. One agent, deep behind Japanese lines and injured by an outraged buffalo, forced Japanese soldiers at gunpoint to build him a raft on the shore of the Chindwin River. Although the raft sank part of the way across, he managed to reach the far shore and deliver his information.

Other enterprising soldiers brought in intelligence bonanzas, like the Border Regiment soldier who came upon a parked Japanese staff car. The soldier shot everybody in the car and decamped with an armload of priceless documents, all the plans for the movement of a major Japanese force.

The 161st Brigade, to which the 4th Battalion of the Royal West Kents belonged, had been sent to Kohima once already, then pulled out of the station with the notion of sending it on to Dimapur. Now, April 4, in the nick of time, it was ordered to turn back and hold Kohima, to a chorus of pungent soldiers’ comments about the vagaries of high command.

The brigade was to reinforce a scratch garrison of V Force personnel; some men of the Assam Regiment, the Burma Regiment, and the Assam Rifles; two Mahratta platoons; a Gurkha company; and a composite company of other Indian troops. Gunner Major Dick Yeo would back them up with his 3.7-inch howitzers, entrenched in the commissioner’s garden. This mixed bag of soldiers would be facing an entire division. A welcome reinforcement was some 260 survivors of the Burma Regiment and Burma Rifles elements who had held up the Japanese advance out east. They were bedraggled, tired, and bloody, but they all carried their weapons, and they were still ready to fight.

Leading the 161st Brigade, the West Kents, then less then 500 strong, arrived at Kohima just as Japanese shellfire crashed into the station, destroying many of the battalion’s trucks and much gear. The battalion ran to the most threatened areas and crushed the first Japanese infantry attacks almost without drawing a breath. As the Duke of Wellington said of Waterloo a century and a half before, it had been a very close-run thing.

The rest of the brigade was cut off from Kohima when Japanese units severed the twisting road downhill at Jotsoma, a couple of miles outside the Kohima perimeter. Surrounded, the brigade set up a defensive box with a fine view of Kohima Ridge. There, the brigade beat off all Japanese attempts to move it, littering the ground around the box with bloated Japanese corpses. During the siege of Kohima, the brigade’s artillery, called in by Major Yeo, would shoot dozens of precise, carefully registered defensive fires for the Kohima garrison. Some of the artillery fell as close as 25 yards in front of the infantry holes.

So began the siege of Kohima, one of the pivotal fights of the war against Japan.

Japan Fights Against the Paradox of Assam

The Japanese attacked again and again, often at night, and ferocious, close-in, hand-to-hand fighting was common. The terrain was so tangled, so convoluted, that much of the fighting was decided by platoons and squads, nose to nose with the enemy. Arthur Swinson, in his excellent history of the Kohima battle, put the problem exactly, writing of “the paradox of Assam as a theatre of war; that while the country is so large that it rapidly absorbs vast numbers of troops, it denies the deployment of large formations, operating en masse.”

Individual heroism was commonplace. For example, Lance Corporal John Harman of the West Kents, commanding a section (read “squad”), singlehandedly attacked a Japanese machine-gun position, destroyed the gun’s crew with a grenade, and brought the gun back to his own lines. He then pushed on into a building, which contained huge bread ovens. Harman discovered that the ovens were full of Japanese, so he ran back for a box of grenades. Marching from one oven to the next, Harman pulled the pins on grenades, let the safety-levers pop off for two or three seconds, then tossed them into the ovens. Along the way, he acquired two stunned prisoners, one an officer, and returned to his own lines with a Japanese soldier under each arm. There were 44 Japanese dead in the bakery area, many, if not most, fallen to Harman’s lone attack.

He was not finished. The next day he went alone after Japanese digging in a mere 50 yards from his position. As the section Bren-gunner gave him covering fire, Harman closed with the enemy, shooting four of the Japanese and killing a fifth with his bayonet. Standing erect in the open, Harman walked back toward his own position, as his men shouted to him to run.

Harman refused, perhaps because he would not run from the enemy, or maybe because he was simply too tired to do so. In any case, he was shot down and mortally wounded before he reached safety. His men pulled him into their position and heard his last words. “I got the lot,” said Harman, “It was worth it.” He was dead in five minutes. Harman was posthumously awarded

his country’s highest decoration for courage, the Victoria Cross.

Night Battle on the Tennis Courts

On the night of April 6, the Japanese 58th Regiment put in a particularly heavy attack from the west on the hill features known as DIS and FSD, leaving heaps of dead behind them but reaching the bashas (supply huts). Led by sappers with demolition charges on poles, a West Kent counterattack threw the enemy out, the men fighting through great sheets of flame from the burning bashas. It was, as a Japanese battalion commander wrote, “a crushing defeat for the 58th Regiment.” On the same day the garrison was strengthened by the arrival of a Rajput company which had slipped in through the Japanese lines.

Typical of the confused, close-in fighting was the battle for the deputy commissioner’s bungalow and tennis court. The British held one side of the court, the Japanese the other, and grenades rolled and bounced across the court throughout each night. One enterprising British officer devised a simple V-shaped wooden barrier the troops could knock together and place in front of their foxholes at night. The obstacle would deflect Japanese grenades in the darkness, and the troops removed them in the morning.

The Japanese neither realized what their opponents were doing, nor created anything similar. British troops could take satisfaction when the “bang!” of their grenades going off on the surface of the court or the ground changed to the satisfying “whump” of a grenade exploding in a Japanese hole.

A step at a time, however, the 31st Division pushed closer and closer to the center of the Kohima settlement. One by one, the high-ground strongpoints were submerged, although the Japanese paid for every yard in blood. With water so scarce that at one point the garrison was limited to half a mug per day, the defenders fought on. Aerial resupply was some help. Loads of ammunition, rations, and water dropped in tire inner-tubes kept the men going, but the perimeter was so small that much of the supplies fell beyond the reach of the garrison.

Although both sides were exhausted, with much of the fighting in darkness and a cold mist, the garrison and the attackers still clawed at each other, ferocious and unrelenting. A West Kent Bren-gunner, his weapon jammed, killed a Japanese attacker with a shovel. Another West Kent played dead all day, lying in a trench overrun by the enemy, while the Japanese walked and stacked ammunition on him. Then, with the coming of darkness, he leaped to his feet, sprinted across the notorious tennis court to a friendly trench, and fought on through the night.

As the Japanese came in, screaming, yelling, and blowing bugles, British troops often held their fire until the attackers were no more than 15 yards away, then cut their charging enemy down with rifle, machine-gun, and Bren-gun fire. Any Japanese who got into the British positions were killed with the bayonet and anything else heavy and handy. One West Kent Bren-gunner, knocked unconscious, came to only to discover he was sharing his trench with a Japanese officer; the Bren-gunner killed the intruder with his bare hands, then picked up his gun and went on with the war. Another soldier shot three Japanese in a row as they jumped into his trench.

The Doctors of Kohima

Lieutenant Colonel John Young, the senior doctor, appeared in Kohima on foot, having walked through the Japanese lines to organize the care of the garrison’s many wounded. As the wounded suffered from the cold of Kohima’s elevation, Young led a party of stretcher bearers at night through the Japanese to bring back some 200 blankets from trucks outside the lines. Obstructed by a Japanese sentry, Young killed the man with his bare hands.

Young and the other doctors, two of whom were killed during the siege, worked tirelessly to save as many of the badly wounded as they could. By the end of the siege, the garrison had some 600 seriously wounded men lying in trenches awaiting evacuation. Most of them retained their weapons, with at least one round in the magazine. Nothing could be worse than capture by the Japanese. A fortunate 100 walking wounded, covered only by a Rajput platoon, slipped out through the Japanese at night and reached safety, but the severely wounded could only lie helpless in their open trenches.

The doctors and medics fought desperately to keep the men alive, as medical supplies ran out and Japanese mortar and artillery fire ripped into the dressing station area. At least one mortar round landed squarely in the trench with the wounded, leaving a chaotic mixture of body parts, dead, and newly wounded men. Sometimes even the doctors’ best efforts ended in tragedy, like that of a young surgeon’s successful amputation of a soldier’s leg. Working under fire, the doctor and a medic had just completed the operation when a Japanese mortar shell killed all three men.

High courage was a common value, and not only in the rifle companies. Throughout the siege, Chaplain Randolph tirelessly moved between the perimeter and the wounded, comforting and inspiring. On Easter, the color sergeant in charge of rations, under heavy fire, managed what amounted to a sumptuous meal in the Kohima perimeter. Although two of his cooks had been killed, he still managed stew, potatoes, tea, and an unusual delicacy, sardines. Hauling this feast to the line soldiers as close as 30 yards from the enemy, the sergeant apologized to the riflemen that he had not been able to manage the traditional pink eggs.

“Very Strong and Well-Disciplined”

From the brigade box down the road, the artillery hammered the Japanese with concentrated defensive fires, all orchestrated by the tireless Major Yeo, who called in fire to the end of the siege and beyond. But inside the shrinking perimeter, in spite of some successful resupply from the air, supplies of everything—food, medical supplies, ammunition, and grenades—ran shorter and shorter.

Troops of the British 2nd Division, pushing toward the brigade box at Jotsoma and the beleaguered Kohima garrison, were fighting their way through a series of heavily dug-in Japanese bunkers, taking casualties every step of the way. The Japanese had identified the division, calling it “very strong and well-disciplined.” The fighting was heavy and often hand-to-hand. A Cameron Highlander sergeant major took a Japanese officer’s sword away from its owner and killed him with it, then, apparently liking the weapon, went on chopping at any Japanese within reach.

The Japanese, trying desperately to hold off the British spearhead, suffered appalling casualties. In one counterattack, a Japanese company lost 96 out of a hundred men. British tanks and antitank guns were laboriously moved over the terrible terrain to fire point-blank on the enemy’s dug-in defenses. The fighting continued ferocious and protracted. When a Rajput company was overrun on the road into Kohima, the British artillery forward observer with them had to shoot his way out, killing eight Japanese with his Sten gun.

The 2nd Division was not to be stopped. By April 14, in heavy fighting, battalions of the Dorset Regiment and the Cameron Highlanders had pushed through to join hands with the brigade box at Jotsoma. Still the Japanese hurled troops at the Kohima perimeter, and on the night of April 17, the Japanese broke through exhausted men of the Assam Regiment and the Assam Rifles on a critical hill feature called Kuki Piquet.

Nonetheless, the thin line of the West Kents held, inspired by Sgt. Maj. Haines, blinded by a wound but still cheering on his men. As one Japanese attack after another came in, Haines was led to each point of crisis, roaring encouragement to his men until at last a Japanese bullet killed him. Under the West Kents’ steady fire, and hammered by deadly 3-inch mortar fire directed by Sergeant King, himself badly wounded in the face and jaw, the Japanese assault broke down.

control of a tactically vital tennis court.

Norfolk Ridge

Fighting on in a moonscape of craters, stumps of trees stripped of leaves and branches and draped with parachutes, clouds of flies, and the stench from heaps of bloated, putrefying corpses and body parts, what remained of the Kohima garrison held on until the morning of April 18. On that happy day, the 25-pounder howitzers of 2nd Division, directed by Major Yeo, began hammering the Japanese positions and were followed by low-level strikes by Hurricane fighter-bombers. Behind them came a battalion of the 1st Punjabis supported by tanks. Trucks and ambulances were close behind, and at last the road was open into Kohima. It would stay open.

Behind the Punjabis came a battalion of the Royal Berkshires, and what remained of the West Kents were now free to leave Kohima. They were filthy, their uniforms “fit only for scarecrows,” with “long beards of all hues.” Most had not had their boots off for the duration of the siege, let alone the rest of their uniforms. Sunken-eyed, without sleep, they were tired beyond telling, but they were winners.

With the garrison finally relieved, the British pushed on into the wild hill country around Kohima. Here again the terrible terrain, riddled with Japanese bunkers, made every small advance an ordeal of stamina and blood. On May 6, for instance, Captain John Randle of the 2nd Battalion, Royal Norfolks, already wounded, was leading an attack on GPT Ridge against heavily dug-in Japanese when the advance was held up by Japanese heavy machine-gun fire from a bunker.

In spite of pain from a knee wound only two days old, Randle charged the gun singlehanded and then, hit repeatedly and mortally wounded, stuffed a grenade through the firing slit and covered the slit with his body in case the grenade did not do the job. He, too, would win the VC. The Norfolks went on to carry the rest of GPT Ridge, but at a cost of 120 killed or wounded out of an already understrength battalion. The ridgeline would forever after be called Norfolk Ridge.

“I Will Bring You Down With Me”

Once the monsoon arrived in May—it was early that year—the horror of close quarters combat was compounded by endless torrents of rain. The monsoon season dumped some 400 inches of water on the battlefields, turning the soil to glutinous mud, filling foxholes and bunkers, making trails so slimy that men and animals slid backward almost as often as they managed another step uphill. Even the faithful American mules were hard-pressed to keep their footing, and some slid completely off their trails, rolling and crashing, load and all, down the hillside below.

There was no such thing as dry clothing or shelter from the incessant rain. Replacement battle dress, if you could get it, was immediately soaked, and there was neither place nor way to dry drenched, mildewed clothing. The British got a minimal amount of shelter beneath gas capes, ponchos to American soldiers, but even that small protection served mostly to trap the moisture in already saturated, mud-caked uniforms. Men’s flesh turned fish-belly white and wrinkled, and diarrhea, dysentery, and a variety of fungi and rot were endemic. Great clouds of voracious mosquitoes made life miserable for everybody.

Nevertheless, step by step, hill by hill, bunker by bunker, the British drove Sato’s men from the hills around Kohima. Sato knew his division had been defeated, and engaged in a heated series of messages with Mutaguchi, who could not accept the dismal failure of his entire campaign. “Retreat and I will court-martial you,” signaled Mutaguchi. “Do what you please,” Sato replied. “I will bring you down with me.” At last, on May 31, Sato sent a final message: “The tactical ability of [Mutaguchi’s staff] lies below that of cadets.”

He then shut down his radio and pulled his troops back toward the Chindwin River, leaving rear guards to delay the British as long as possible. The siege of Kohima and the subsequent fighting to drive Sato out had lasted 64 days. It had cost the British and Indian troops some 4,000 casualties, while the Japanese losses were about double that figure.

A Costly Campaign for the Japanese

The Imphal-Kohima campaign was a triumph for the British and Indian soldier and his junior leaders, both officers and NCOs. The officers, General Slim wrote, “made me proud to belong to the same army.” Almost with reverence, he told the story of a young lieutenant colonel, commanding a rifle battalion, who led his men in spite of a bad stomach wound from grenade fragments. He remained in command even when he took a second wound, this time in the shoulder. The officer made light of his wound. “The bullet,” he said, “has passed straight through my shoulder so it causes me no inconvenience.” Sadly, when Slim inquired after him to promote him to command of a brigade, he found the youngster had been killed in action.

The campaign was an unmitigated disaster for the Japanese, a beating from which they never recovered. One Japanese writer called the defeat “the worst of its kind yet chronicled in the annals of war.” Toward the end of June, Slim’s troops reopened the road between Dimapur and Imphal, and less than a month later the Japanese began to fall back across the Chindwin. Of some 85,000 troops engaged against the British, about 53,000 became casualties, three times the British losses. As many as 30,000 rotting Japanese corpses littered the hills and jungles, and many more were dead of malnutrition and disease. A great many of the dead were irreplaceable veterans.

Slim pursued and methodically drove the Japanese first east and then south, one British corps advancing 250 miles in just 19 days. In one last spasm of fighting along the Mandalay-Rangoon road, the Japanese took some 17,000 casualties. The British lost just 95. On August 28, the Japanese command surrendered. The longest land war against Japan was over, and the beginning of the end had come high in the Naga Hills, at a little hill station called Kohima.

Mountbatten visited Kohima on July 1, and made “special note of the grave of the Royal West Kents where they had held out with great gallantry.” There, the battalion’s pioneers had raised a large wooden cross, carved by one of its sergeants. It stands today in England, at the regimental museum in Maidstone. It is a gentle reminder to tourists, some of whom are only vaguely aware of either World War II or Burma, that peace and safety are always bought in the dearest coin of all, the blood of men.

Robert Barr Smith is a frequent contributor to WWII History. He is a retired U.S. Army colonel and is a professor of law at the University of Oklahoma Law Center in Norman.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments