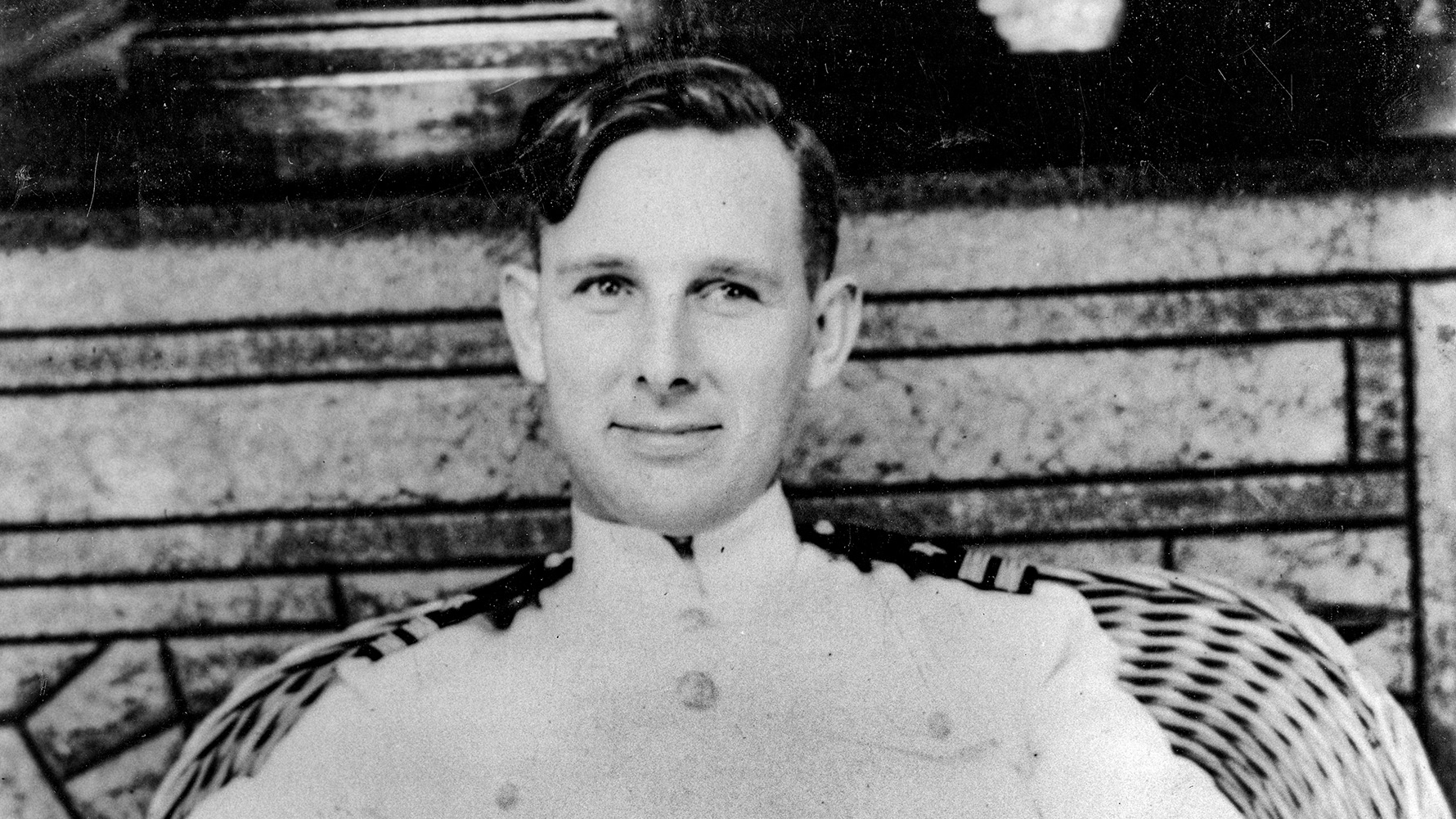

When a 21-year-old New Mexico boy began drawing cartoons for the 45th Division News, that outfit’s weekly newspaper, just about everybody was amused. His ready wit and the humorous situations his dogface heroes Willie and Joe found themselves in endeared the young journalist to millions.

One officer, however, did not see the work of Bill Mauldin as particularly helpful to the war effort. In Sicily, General George S. Patton, commander of the Third Army, remarked that Mauldin

“set such a damned bad example with his unsoldierly Willie and Joe.” Patton ordered Major General Troy Middleton, commander of the 45th Division, to put Mauldin out of business. When Middleton retorted, “Put your order in writing, George,” the matter was dropped.

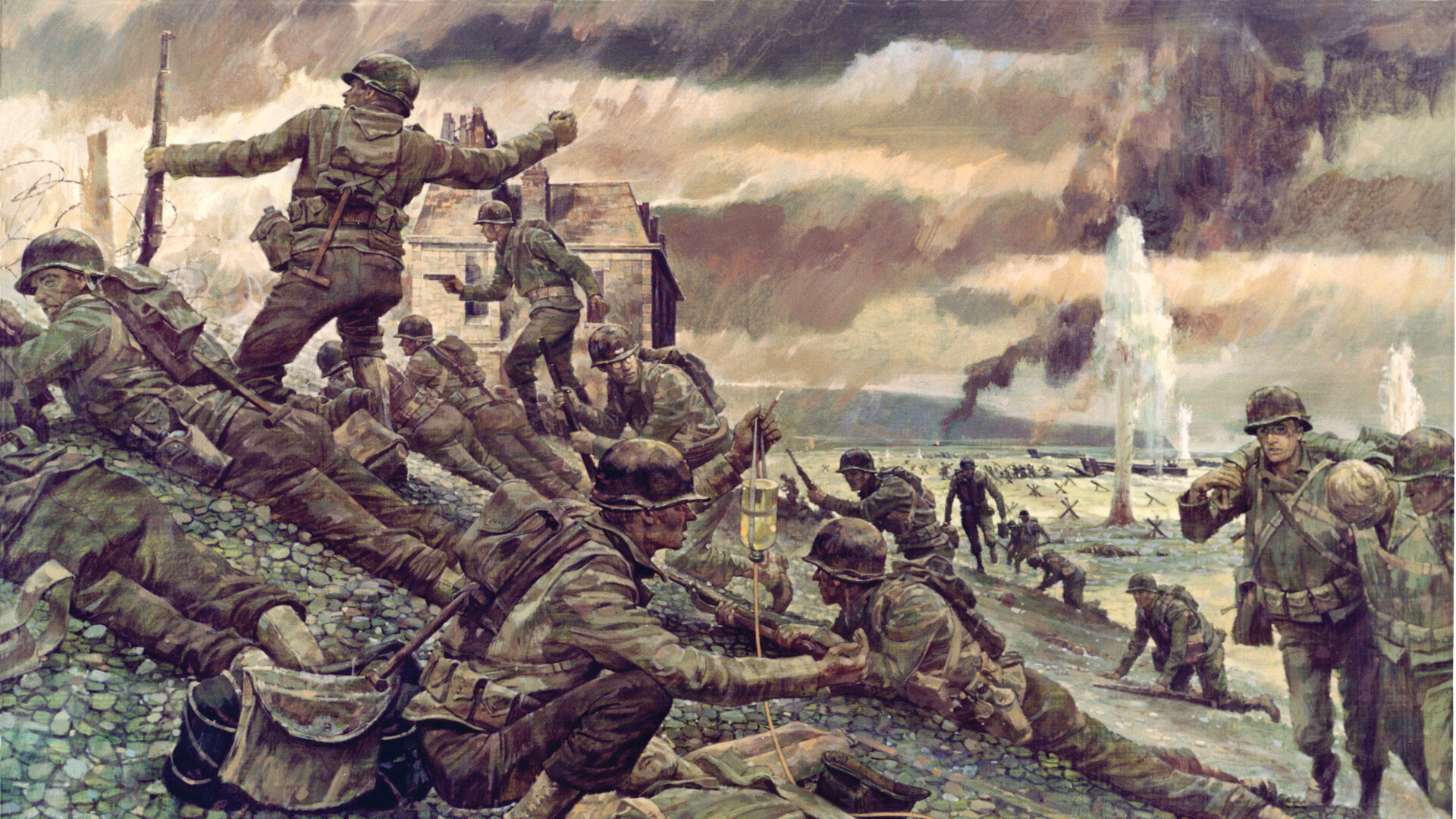

Willie and Joe were too popular. In fact, it was their very “unsoldierly” look and their barbed criticism of military life that made them real to the troops fighting the Nazis.

Mauldin passed away at the age of 81 in a Newport Beach, California, nursing home on January 22, 2003. Although Alzheimer’s Disease had robbed him of his memories, he left a legacy of great editorial cartoons. His book, Up Front, had become a classic of World War II literature, and he had received two Pulitzer Prizes. The first Pulitzer had come in 1945, when Mauldin was only 23 years old, for his cartoon series “Up Front With Mauldin.”

Willie and Joe were the iconoclastic everymen to the American GI in World War II. Their unshaven, mud-splattered, hollow-eyed countenances were real, and they spoke their war-weary minds. In one image, the pair runs across a drunken German soldier stumbling down a road. One tells the other not to scare the German because the bottle he carries is still half full.

Mauldin studied for a year at the Academy of Fine Arts in Chicago and entered the Army at the age of 18. Pulling similar duty to what one would expect of his cartoon subjects, he worked more than 60 days of kitchen patrol (KP) during his initial four months in the service. His work reached a wider audience and his fame grew steadily when Mauldin went on to draw cartoons for the Army’s Stars and Stripes during the Italian Campaign.

Lieutenant General Lucian K. Truscott commanded the 3rd Infantry Division in Italy. He once told the young cartoonist, “When you start drawing pictures that don’t get a few complaints, then you’d better quit because you won’t be doing anybody any good.” Mauldin was wounded in Italy and received the Purple Heart. Routinely, he would spend three days at the front and return to the Stars and Stripes offices in Naples to create new vistas of the soldier’s life of hardship.

After the war, Mauldin continued to draw political cartoons, holding a mirror up to society and provoking thoughts about racism and McCarthyism. He worked in the editorial departments of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and the Chicago Sun-Times. His second Pulitzer came in 1959 for a cartoon entitled, “I won the Nobel Prize for Literature. What was your crime?” When President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in 1963, he created a memorable drawing of a distraught President Abraham Lincoln, crying with his face buried in his hands. Mauldin authored or illustrated more than a dozen books during his career and became the father of seven sons.

Describing Willie and Joe in Up Front, Mauldin said that their faces were “those of infantry soldiers who have been in the war for a couple of years…. If he is looking very weary and resigned to the fact that he is probably going to die before it is over, and if he has a deep, almost hopeless desire to go home and forget it all; if he looks with dull, uncomprehending eyes at the fresh-faced kid who is talking about all the joys of battle and killing Germans, then he comes from the same infantry as Joe and Willie.”

Bill Mauldin’s great contribution to the understanding of World War II lies in his unique perspective of the soldier’s life and his ability to convey that to those who have never or will never experience it. Mauldin will remain not only one of the foremost journalists of the war, but also of the 20th century.

Michael E. Haskew

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments