By Robert F. Dorr

A little-known sidelight of the Pearl Harbor attack is the air-to-air fighting that went on in the skies of Hawaii on December 7, 1941. Most of this combat occurred between Curtiss P-40B Tomahawks of the Army’s 47th Fighter Squadron and Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero fighters of Japan’s First Air Fleet (1st Koku-Kantai). A tiny handful of Hawaiians actually heard the whine of engines and the chatter of machine guns as Tomahawks and Zeros dueled in the Sunday sky.

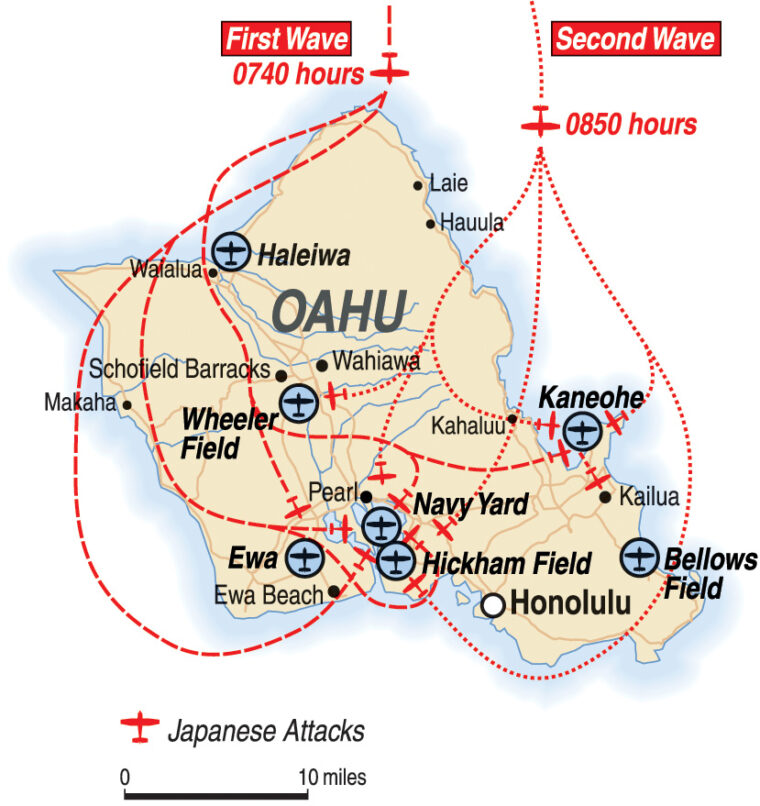

At Hickam Field just outside Honolulu, base commander Colonel William Farthing said it was “only human ingenuity” that enabled a few Army pilots to climb aloft and engage the attackers. Farthing’s boss in the islands was Lt. Gen. Walter C. Short, who expected Japanese sympathizers on Oahu to try to blow up aircraft and equipment. To cope with the anticipated sabotage, Short had ordered his Army Air Forces (AAF) commanders to park P-36s, P-40s, A-20s, and B-18s wingtip-to-wingtip on the flight lines at Hickam, Wheeler, Bellows, and other airfields.

At Short’s direction, the islands’ radar sites operated on a part-time basis and were scheduled to shut down at 7 am, 53 minutes before the attack began that Sunday morning. On December 7, 1941, Farthing was in the control tower early, awaiting the arrival of a flight of Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers from the mainland scheduled for 6 am. They were delayed, and Farthing saw the first aircraft of the Japanese attack hit ships in the harbor before they moved on to strafe the airfield.

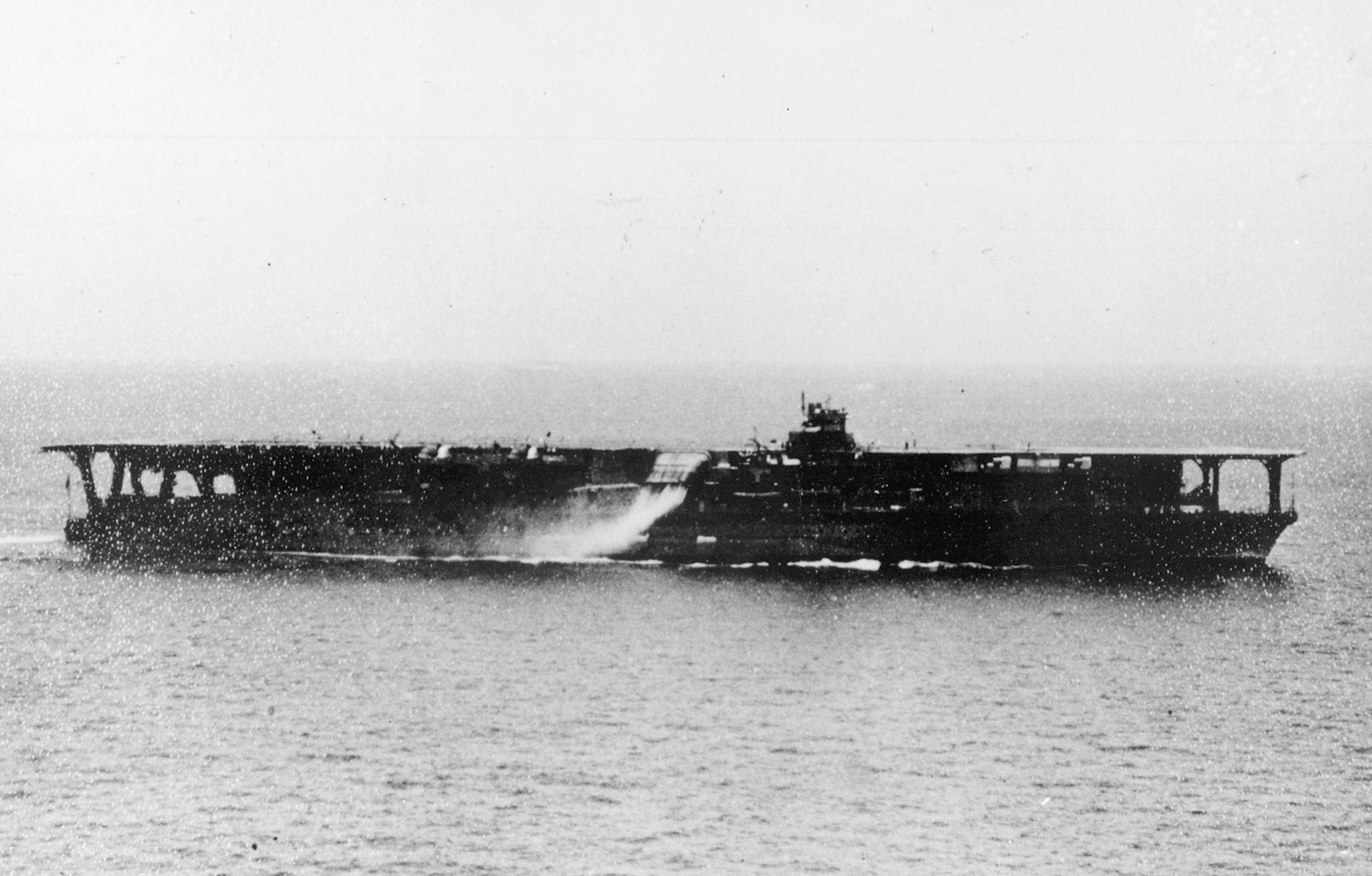

Farthing was not in the loop when the radar technicians decided they were watching the B-17s. There were, in fact, four B-17Cs and eight B-17Es approaching, just three degrees off the heading of the Japanese warplanes. But there were also 170 torpedo bombers, dive-bombers, and fighters arriving over Oahu from six Japanese aircraft carriers.

The Japanese battle plan stressed the importance of neutralizing AAF airfields on Oahu, lest the Americans employ long-range aircraft to shadow departing Japanese planes back to their carriers. These airfields boasted the 18th Bombardment Wing at Hickam Field, the 14th Pursuit Wing at Wheeler Field, and a gunnery training detachment at Bellows Field. The Air Force had 754 officers and 6,706 enlisted men in the islands. Its aircraft were out of date by any standard, 12 B-17D Flying Fortresses and 33 B-18 Bolo bombers, 39 P-36A Mohawk and 87 P-40B and 12 P-40C Tomahawk fighters. On December 7, few of the fighters had fuel or ammunition aboard. “We did not anticipate what came,” said Lt. Col. Gordon Austin, commander of the pursuit wing’s 47th Pursuit Squadron.

More worried about these U.S. aircraft than proved necessary, the Japanese struck not only Pearl Harbor but also Hickam, Wheeler, and Bellows Fields. The first wave of strafing runs at Wheeler and Hickam destroyed aircraft, maintenance hangars, and other structures. More were wiped out in the second wave an hour after the first. The second attack also hit Bellows Field. By the end of the day, 700 AAF personnel were dead and wounded, and two-thirds of the air power on Oahu was damaged or destroyed.

The only B-24A Liberator four-engine bomber within thousands of miles abruptly achieved the distinction of being the first American aircraft to be lost in World War II. First Lieutenant Ted Faulkner, detached from the 7th Bombardment Group, was readying the Liberator for a very secret photo reconnaissance mission to the Caroline Islands aimed at detecting any offensive naval movements by Japan. Aichi D3A Type 99 “Val” dive-bomber pilot Lieutenant Kunikiya Hira from the carrier Shokaku dropped the first bomb on Hickam, hit Hangar 15, and set Faulkner’s B-24A ablaze, killing two of its crew.

Arriving from the West Coast on what was supposed to be a routine flight, a dozen Flying Fortress bombers were suddenly scattered all over the skies of Oahu. A cohort of Faulkner’s, 1st Lt. Frank P. Bostrom of the 7th Bombardment Group, failed during several attempts to land, evaded Zeros, and put down on the Kahuku Golf Course. Bostrom would later achieve fame for carrying out the second phase of General Douglas MacArthur’s evacuation from the Philippines to Australia.

Austin, 47th Pursuit Squadron commander, later recalled, “The odds were against any of us getting into the air that morning.” In fact, several fighter pilots did.

Second Lieutenants George Welch and Kenneth Taylor, both new fighter pilots, were awakened at Wheeler Field by exploding bombs. They raced outdoors and saw smoke rising over Pearl Harbor. Taylor telephoned the grass airstrip at Haleiwa, 10 miles from Honolulu, where the 47th had been sent for target practice. He told ground crews to have two P-40B Tomahawks fueled and armed for combat.

The two pilots were strafed while they drove at high speed to Haleiwa. They took off in two P-40Bs only partly loaded with machine-gun rounds. They attacked a formation of Nakajima B5N2 “Kate” bombers. Welch and Taylor each shot one down. Moments later, Welch’s

P-40B was hit with rounds from a Japanese tail gunner. Still, he and Taylor shot down another Kate apiece.

Welch and Taylor landed at Wheeler to refuel, rearm, and take off again. Welch ultimately flew three sorties and was credited with shooting down four Japanese aircraft including a Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero fighter. Among just half a dozen airmen who fought back that day, Welch and Taylor were each awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Over the years, the legend has grown that Welch was recommended for the Medal of Honor but that the military squelched it because he had taken off without authorization. By one account, the brass did not want to publicize its defeat at Pearl Harbor. In a contradictory version, the award was killed because a hero was needed immediately and, “it would have taken too long for Congress to act.”

None of this is true. Welch’s bravery was real and was recognized with the nation’s second highest award.

Welch, however, was not nominated for the top award. He needed no authorization to take off in his P-40B. As for shunning publicity, the military awarded Medals of Honor with much fanfare to 15 others for Pearl Harbor. It required no act of Congress, since the executive branch gives the award.

Also at Wheeler, 2nd Lt. Philip M. Rasmussen struggled with fellow pilots to arm and fuel P-36 Mohawk fighters of the 15th Pursuit Group. Rasmussen, too, had awakened abruptly and was still attired in his purple pajamas. Amid noise and chaos, he managed to get airborne in the clunky, obsolete P-36. “We climbed to 9,000 feet and spotted Val dive bombers,” Rasmussen said later. “We dived to attack them.”

Rasmussen, 1st Lt. Lewis M. Sanders, and two other P-36 pilots tore into a Japanese formation. Although his P-36 was slower than any of the Japanese aircraft in use that day, Sanders got behind one of the raiders and shot it down. Second Lt. Gordon H. Sterling, Jr., also shot down a Japanese aircraft but then was himself shot down over water and drowned after getting out of his aircraft. Just before witnessing Sterling’s death, Rasmussen charged his guns only to have them start firing on their own. While the pajama-clad pilot struggled to stop his guns from firing, a Japanese aircraft passed directly in front of him and exploded.

Shaking off two Zeros on his tail, Rasmussen got his guns under control, raked another Japanese aircraft with gunfire, then felt himself taking hits from a Japanese fighter. “There was a lot of noise. He shot my canopy off.” Rasmussen lost control of the P-36 as it tumbled into clouds, its hydraulic lines severed, the tail wheel shot off. He did not know it yet, but two cannon shells had buried themselves in a radio behind his pilot’s seat. The bulky radio had saved his life.

Probably the most frustrated American that morning was Gordon Austin, the P-40 pilot who commanded the 47th Squadron. After a flip of the coin with his operations officer, Captain Bob Rogers, he had decided to give his men that Sunday off. Austin and a few others took a B-18 bomber and flew over to the island of Molokai to go hunting and to scout out possible aerial gunnery locations. When they first heard about the attack, they did not believe it. “There had been so many alerts, I figured it was another one,” he remembered.

Austin flew the B-18 back to Wheeler to find all of his aircraft at that base (unlike the ones at Haleiwa, which was untouched) shot to pieces along with buildings, people, and his ’41 Mercury sedan. He believes that if squadrons had prepared for air attack, instead of ground sabotage, most of his P-40s would have gotten into the sky.

First Lieutenant Annie Guyton Fox, chief nurse at Hickam Field, awakened in her quarters that morning to hear a crescendo of noise. On that fateful morning, 82 Army nurses were serving in the Hawaiian Islands at Tripler Army Hospital, Schofield Hospital, and—at the airfield—Hickam Station Hospital.

Second Lieutenant Monica Conter was one of them. She had been on a date with Army 2nd Lt. Barney Benning (later to be her husband of more than 60 years) that Saturday night. “We noticed that … there were Navy people all over the place,” while at a dance at the Pearl Harbor officers’ club, Conter recalled. “The fleet was in. Barney and I decided to take a walk, so we went down to the harbor. It was the most beautiful sight I’ve ever seen, all the battleships and the lights with the reflection on the water. We were just overwhelmed.”

At 7 am on December 7, 50 minutes before the attack, Conter reported for duty at Hickam with 2nd Lt. Irene Boyd. They were the only nurses on duty. “We heard this plane. It was losing altitude. We both just stopped suddenly and stared at each other. Then—bang!”

In front of Conter’s eyes, a 500-pound bomb landed on the front lawn of the hospital and did not explode. The bomb was 60 or 70 feet from patients. Some detected what they thought was a peculiar smell and began shouting: “Gas! Gas!” Some troops at Hickam had donned gas masks.

Nurse Fox arrived and organized her team of eight nurses to assist wounded as they were brought in. Conter, Kathleen Coberly, and others improvised, provided a steadying influence, and handled more patients than they had ever expected to see. Later, Fox became the first of many Army nurses to receive the Purple Heart medal, usually given to those wounded by enemy action. Unwounded, Fox received her medal for “her fine example of calmness, courage, and leadership, which was of great benefit to the morale of all she came in contact with.”

A flight surgeon who had arrived on one of the B-17 Flying Fortresses, 1st Lt. William R. Schick, sat on the stairs to the second floor of the hospital attired in winter uniform (never worn in Hawaii) and bleeding profusely from his head and face. Schick repeatedly refused medical care, pointing to casualties on litters on the floor and urging responders to, “Take care of them.” Despite his resistance, Schick was put aboard an ambulance for Tripler but died before arriving there. Today, Hickam’s hospital is named for Schick.

P-36 pilot Rasmussen navigated his way to smoke-shrouded Wheeler Field, where detonations continued to resound and airplanes burned. Rasmussen landed his P-36 without brakes, rudder, or tail wheel, and with dozens of bullet holes in the rear fuselage. There was no other aircraft available, so Rasmussen’s day was over. He was awarded the Silver Star, shot down a second Japanese aircraft in 1943, and still lives in Hawaii today.

A second wave of Japanese air attacks came swarming down on Oahu while American pilots took off individually from two different airfields, sometimes joining up after getting airborne. Welch took off on his second P-40B sortie while Taylor waited until what he thought was the last in a line of Japanese aircraft passed overhead, then took off again in a P-40B, seeking to get them in his gunsight.

Welch spotted a Zero locking onto Taylor’s tail. He maneuvered behind the Zero, fired short bursts, and racked up his third kill of the day. Subsequently, Welch flew to Ewa, found a lone Japanese aircraft, and shot down his fourth for the day. Later in the war, Welch would become a 16-kill ace; as a test pilot he would pioneer jet aviation but lose his life in an F-100A Super Sabre in 1954. Taylor would reach brigadier general rank; he lives today in Alaska.

Over at Bellows Field, 1st Lt. Samuel W. Bishop and 2nd Lt. George A. Whiteman attempted to take off in another pair of P-40Bs. Bishop got aloft, but Zeros swarmed over him and he went down in the ocean. Whiteman was hit as he cleared the ground and went down in his aircraft off the end of the runway. Bishop was only wounded and swam ashore, but Whiteman lost his life.

Six other pilots got aloft from Wheeler in P-36s and P-40s. Second Lt. John Dains ended up flying three sorties, two in a P-40B and one in a P-36, and apparently shot down a Zero that was observed falling from the sky by AAF radar operators at Kaawa. This aerial victory cannot be linked to any other pilot in the air that day, but it is unclear whether Dains was on the scene shortly before he was shot down and killed by U.S. antiaircraft fire. First Lieutenant Harry Brown apparently scored the last confirmed kill of the day when he shot down a Zero as it headed out to sea. The second and final wave of the attack was over.

At Hickam, Douglas A-20A Havoc attack bombers of the 58th Bombardment Squadron had been battered and burned by Japanese strafing and bombing. As the second wave of Japanese aircraft retired, the 58th went aloft to search for and attack a Japanese carrier reported (incorrectly) to be south of Barbers Point on Oahu. At 11:27 am, after bombs and fuel had been loaded with great difficulty, Major William Holzapfel led four A-20As into the air. It was too late.

The Pearl Harbor attack, which killed 2,403 people, most of them American servicemen and wounded 1,104 others, was over. The Japanese conceded the loss of 29 aircraft, of which the AAF downed 10 (including six by Taylor and Welch). Casualties would surely have been higher but for the initiative of doctors and nurses who improvised on the scene. n

Robert F. Dorr is an author on military issues and the Air Force. He served 24 years as a Foreign Service officer with the Department of State and writes a weekly column for the Air Force Times. His latest book is Air Force One.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments