By Nathan N. Prefer

By the spring of 1943, the Japanese advance across the Pacific had been brought to a halt. In the South Pacific, General Douglas Macarthur’s Southwest Pacific Theater of Operations was beginning its laborious climb up the north coast of New Guinea, destination the Philippines.

Launching from recently captured South Pacific islands, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz’s Central Pacific Theater of Operations was about to launch a counteroffensive as well. It, too, had an ultimate destination of the Philippines and then Japan itself.

In the North Pacific, also under Nimitz’s command, the defensive buildup of the Aleutian Islands of Kiska and Attu, recently recaptured from the Japanese, were well underway. With the direct threat to the United States and Canada eliminated, planners could look elsewhere.

“The attack upon the Gilberts was for the Central Pacific the counterpart of that upon the Solomons (August 7, 1942).” Said the Army’s official history of the campaign. To Admiral Nimitz, the Gilberts were “another road to Tokyo.”

These Gilbert Islands lie along the equator 2,000 miles southwest of Hawaii. Most are low, coral atolls that rise only a few feet above the sea. Vegetation is limited to palm trees, breadfruit trees, mangroves, and sand brush.

Makin Island had been seized by the Japanese on December 10, 1941, in the opening days of the war, and developed into a seaplane base and communications center. Later the Japanese would also seize the Gilbert Islands of Tarawa and Apamama. Air bases were later developed on Tarawa, Ocean, and Nauru Islands, while Apammama became an observation outpost.

The Gilberts, with the Marshall Islands to their west, were a part of an interlocking system of defense for the Japanese. From the Gilberts, they could observe American military movements—and their submarines and aircraft could harass the American fleets. The possession of these islands by Japan was a threat to any planned Allied offenses in the Pacific and therefore had to be taken from the enemy.

Makin Island was first attacked by a U.S. Navy task force in January 1942, barely a month after its capture. The next several months were peaceful on Makin, until August of that same year when 220 Marine Raiders of Lt. Col. Evans F. Carlson’s 2nd Marine Raider Battalion were deposited on the island, destroying most of the Japanese installations and troops there.

Beginning in January 1943, Major General Clarence Tinker’s Seventh Army Air Force (previously the Hawaiian Air Force) regularly raided Makin Island as weather and aircraft availability allowed.

By July 1943, the Joint Chiefs of Staff decided that there were enough resources now available to undertake an offensive against the Gilbert Islands, removing that threat against Allied communications and paving the way for future advances across the Pacific.

One Army and two Marine divisions were needed for the offensive; the target date was tentatively set for November 15, 1943. Besides seizing the Gilbert Islands to the advantage of the Americans, this would also put the Japanese under a new source of pressure, opening a Central Pacific front.

Further, it was planned that the Gilbert Islands would be a springboard to the Marshall Islands the following January. Admiral Nimitz, in his role as Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas, would be in overall command. Tactical command rested in Major General Holland M. (“Howlin’ Mad”) Smith, USMC, and his V Amphibious Corps staff. Planning and the gathering of forces began at once.

The Gilbert Islands campaign was an early amphibious warfare experience in atoll warfare. Every item had to be planned and prepared for as, once committed, the combat troops had to fight with what was immediately available, since their nearest friendly base would be 2,000 miles away.

During this planning, it was decided that one target, Nauru, was too strongly defended for the available strength of the planned attacking force. It was also deemed too far from Tarawa and Apamama, the other targets, to be mutually supporting.

The objective instead became Makin and the Army’s 27th Infantry Division was selected as the assault force. The veteran 2nd Marine Division would seize Tarawa and Apamama. When this change was made, the division staff of the 27th Infantry Division had barely six weeks left to plan their part of “Operation Galvanic.”

The Army division had other problems as well. A National Guard division from New York State, the 27th had been federalized early and rushed to Hawaii, where it was assigned as the defensive garrison of the outer islands. Because of the latter responsibility, and the fact that the division was spread over several islands, it had rarely trained in units larger than a battalion, perhaps a regiment.

It had no infantry-armor training, despite having its own National Guard tank battalion attached to it. Infantry-artillery cooperation was rare. Amphibious training had only recently begun. Makin Island would be its first combat assignment.

The division commander was Major General Ralph Corbett Smith. A graduate of Colorado State College, he had been commissioned into the Infantry in 1916 and fought in France during World War I, where he earned two Silver Stars and a Purple Heart. He was an instructor at West Point and the Infantry School before graduating from the Command and General Staff School in 1928.

He followed this by becoming an instructor at the Command and General Staff School before graduating from the prestigious Army War College in 1935. Fluent in French, he studied in France at the Ecole Superieure de Guerre before serving in the Military Intelligence Branch of the War Department General Staff.

By 1942 he was a brigadier general, a respected tactician, and assistant division commander of the new 76th Infantry Division. When a vacancy arose, the Army appointed him commander of the 27th Infantry Division.

Newly appointed Lieutenant General Ralph C. Richardson, Jr., now commanding U.S. Army Forces, Central Pacific Area, tried to better prepare the novice infantrymen for their coming assignment. In addition to training with ropes, boats, transports and barbed-wire entanglements, he ordered training centers opened to familiarize the ground pounders with amphibious tactics and acquaint them with the naval officers and sailors they would be working with in the coming operation. Shore-fire control parties were attached to the division.

The War Department Field Manual 31-5, Landing Operations on Hostile Shores (1941) was used as a basis for training. This manual, derived almost entirely from the Marine Corps’ amphibious manual issued in 1934-35, was the doctrine taught to the soldiers. But even General Richardson admitted that there was no time for everything in the brief time left after the change of targets, and he specifically regretted that there was no time for infantry-armor training in Hawaii.

Poor weather conditions also limited the actual amphibious training that was practiced. Lack of available fire support ships further eliminated some reality from the exercises.

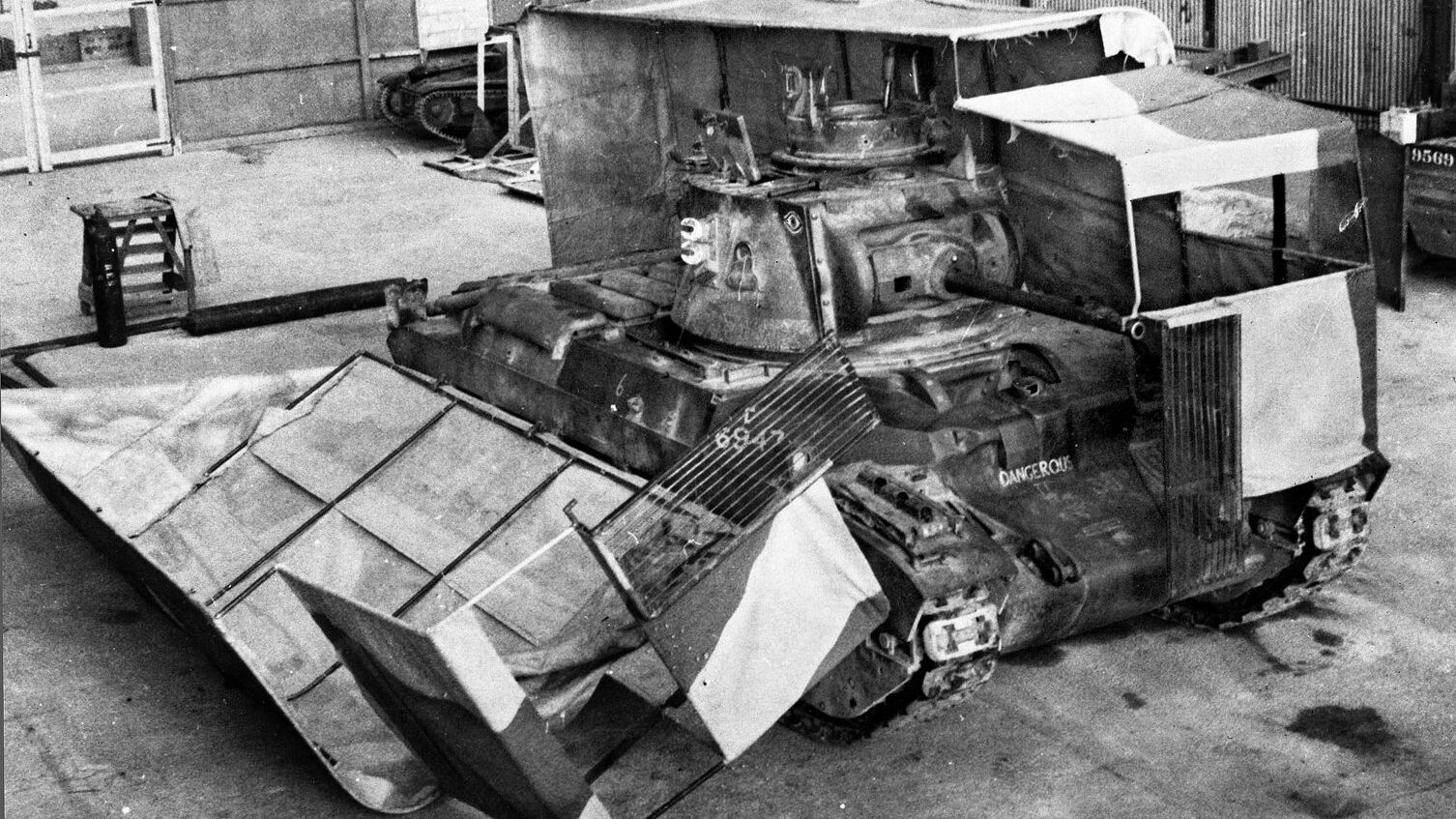

Logistic problems also hampered preparations. Planners determined that it would be necessary to use the new amphibian tractors (LVTs) to get the assault troops over the reefs surrounding both Tarawa and Makin, but few were yet available.

The New Yorkers had only one such vehicle with which to train until a supply reached them less than two weeks before the attack. Even then, only 48 were received, less than half that received by the 2nd Marine Division. A provisional company drawn from the Army division’s 193rd Tank Battalion was hastily created to train on these new vehicles.

The division did succeed in another area, however. Copying from the experience of the 7th Infantry Division in the Aleutians campaign, the division “palletized” nearly all its supplies. This involved stacking all sorts of supplies on sled-like structures to which they were then strapped. This made logistical movement of supplies faster, easier, and more compact. Later in the war, palletizing would become commonplace.

The first section of the assault force sailed from Hawaii on October 31, 1943. Two thousand miles to the west the Japanese on Makin Island were waiting; that garrison had been strengthened after the Marine Raiders’ visit the previous year. Troops from the Marshall, Caroline Islands, and Japan itself were rushed forward to garrison all the Gilbert Islands, including Makin.

A company landed on Makin from Jaluit on August 19, followed by more air-transported troops and equipment. The nine Marines abandoned by the Carlson raid were captured and executed. Nauru and Ocean Islands, previously left alone, were seized.

The 5th Special Base Force sailed from Saipan to Makin to become its defense. The Yokosuka 6th Special Naval Landing Force (later renamed the 3rd Special Base Force) was rushed to the Gilberts and its 1,509 men divided between Tarawa and Makin Islands. Most of the 6th Special Naval Landing Force followed suit later.

The Australian and New Zealand coastwatchers who had provided so much valuable intelligence for the Allies had to flee for their lives. The airbase on Makin was reopened by July 1943 and coastal defenses were installed. American Seventh Army Air Force attacks hindered, but did not halt all this progress.

When the first ships of the American task force destined for Makin Island sailed into Japanese view, there were 798 officers and men on the island, including 284 from the 3rd Special Base Force, under the command of Lieutenant (j.g.) Seizõ Ishikawa. These were the only infantry-trained troops on the island. The rest, more than half, were non-combat troops such as air personnel, construction personnel (mostly Koreans), and a 4th Fleet Construction Detachment.

Lieutenant Ishikawa had little with which to defend his island. There were three dual-purpose 8cm guns defending the main installations at what was known as King’s Wharf, in the island’s lagoon. Several machine guns were also available. Two extensive tank barriers had been built running entirely across the island’s width. Known to the Americans as the East and West Tank barriers, they consisted of wide ditches and coconut log barriers 12 feet wide and nearly five feet high. Each was protected by a single pillbox, an antitank gun, 6 machine guns and 50 infantrymen.

Barbed-wire obstacles had also been laid across the entire island, and rifle pits abounded. A 70mm howitzer had been placed to defend against a landing on the ocean shore, as had the three 8cm guns. Clearly the Japanese expected the Americans to follow Carlson’s plan and attack from the ocean side.

The assault force for Makin Island was carried to the Gilbert Islands by Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner and his amphibious Task Force 54. The assault troops were drawn from Colonel Gardiner J. Conroy’s 165th Infantry Regimental Combat Team, the former “fighting 69th” of World War I fame. Tanks of Company A, 193rd Tank Battalion, would support the landing.

“Instead of delivering an assault of maximum power at any one point, the schedule called for two separate landings, one following the other, after an interval of about two hours,” said the official history. The 1st and 3rd Battalions would land first, on the ocean (west) side, followed by the reserve 2nd Battalion two hours later, on the lagoon side.

Each battalion would be preceded by what was termed a “Special Landing Group” made up of men from the 3rd Battalion, 105th Infantry Regiment. Each of these groups would land first from 16 LVTs. Naval gunfire and air bombardment support from four battleships, four cruisers, and nine aircraft carriers would support the landings.

Even as the convoy approached Makin Island on November 20, it came under air and submarine attack from the Japanese. These attacks, after several close calls, availed them nothing. But during this approach, three Landing Ships, Tank (LSTs) carrying the LVTs and Lt. Col. Harmon L. Edmundson’s tanks became lost in the darkness. They were located and properly placed while the pre-invasion bombardment was underway.

While this bombardment continued, 19 Marines of the 4th Platoon, V Amphibious Corps Reconnaissance Company under 1st Lt. Harvey C. Weeks, USMCR, and the 2nd Platoon, Company G, 2nd Battalion, 165th Infantry, under 2nd Lt. Earl W. Montgomery, sailed in LCVPs for Kotabu Island, a small, round island about four miles from Makin, to secure that flank of the landing.

At Makin, the landings of Lieutenant Colonel Gerard W. Kelley’s 1st and Lt. Col. Joseph T. Hart’s 3rd Battalions, 165th Infantry, on the Red Beaches were unopposed. Major Edward T. Bradt, commanding the “Special Landing Groups” drawn from his 3rd Battalion, 105th Infantry, recalled, “I jumped down from my boat and stood straight up for two or three minutes, waiting for somebody to shoot me. Nobody did! I saw many other soldiers doing the same thing.”

Follow-up troops were immediately ordered ashore, and the word went to Lt. Col. John M. McDonough to land his 2nd Battalion, 165th Infantry, on Yellow Beach.

The advance from the Red Beaches began quickly and met little in the way of resistance. Coast-defense guns were found to be dummies, just logs painted to look like guns. Three enemy strongpoints identified by intelligence behind the beaches proved to be equally harmless.

It wasn’t until the advance troops had moved well inland, and two hours after the landings, that the first opposition was encountered when a small enemy patrol resisted the advance and was wiped out. Behind the advance engineers, signalmen and gunners of the 93rd Coast Artillery (AA) Battalion set up shop. Colonel H.G. Browne positioned his supporting 105th Field Artillery Battalion as planned at the village of Ukiangong. All was going according to plan.

In the lagoon, Colonel McDonough’s battalion, reinforced with “Special Landing Group Z,” Company A, 193rd Tank Battalion, a platoon of Company C, 102nd Engineer Combat Battalion, and some guns from the 98th Coast Artillery (AA) Battalion loaded into their assault boats and began the run to the Yellow Beaches.

Watched by the U.S. Marines and soldiers on otherwise empty Kotabu Island, the landing team sailed into heavy smoke and dust raised by the bombardment. Covered by fire from destroyers USS Phelps (DD-360) and USS MacDonough (DD-351), the battalion sailed into the heart of the Japanese defenses on Makin Island. Yet, for some reason, reports by Army officers observing the attack mentioned that the infantrymen seemed “in a gay and confident mood. Many were inattentive to the tumult; some even slept.”

Fearing “friendly fire,” the assault waves stopped for a few minutes to let the naval guns and aircraft clear the area before proceeding ashore. When the assault resumed, enemy fire was encountered about 500 yards from shore. Enemy machine guns hidden in sunken wrecks within the lagoon opened fire. An enemy patrol boat in the lagoon also opened fire while hidden machine guns ashore contributed their voices to the growing battle.

As they landed, the soldiers jumped clear of their landing boats and raced for cover from this fire. Several landing craft became disoriented and wandered around, one even going completely across the narrow island until it was ditched in a large shell crater. Squads immediately set about clearing the immediate area and the two destroyed wharfs (Kings and On Chongs) of enemy troops and guns.

Fortunately, opposition was light, and the “Special Landing Force’s” mission was accomplished. Follow-up troops and tanks soon landed and set about clearing the area entirely. Two tanks were drowned in shell holes, while others became stuck on shattered tree trunks. The tank advance then stalled, with Captain Robert S. Brown, the company commander, stuck offshore in a drowned-out tank.

A miscalculation of the water depth forced many soldiers to wade ashore under fire, carrying their equipment, and struggling in water sometimes neck deep to reach the beach. Radios, flamethrowers, and bazookas were damaged by the immersion. Surprisingly, only three fatalities resulted from this episode.

The battle at Yellow beach continued for several hours, with a particular annoyance: those machine guns hidden in the sunken hulks in the lagoon. Finally, the landings were halted and U.S. Navy aircraft from the USS Enterprise (CV-6), USS Coral Sea (CVE-57), USS Corregidor (CVE-58) and USS Liscome Bay (CVE-56) bombed the hulks, with little success.

The fighting ashore continued, with the infantry clearing out the numerous enemy shelters in the area. A score of Japanese were killed, and 35 captured, the latter being Korean laborers.

As directed, the battalion set out to cut the island in two and contact the other battalions of the 165th Infantry on the left. It was during this move that they rescued Lieutenant Charles Hough, of Company L, 105th Infantry, whose group had been trapped in that landing craft that had raced across the island in the early moments of the landings on Yellow Beach.

Two men had been killed and others, including Hough, wounded as they fought off attacking enemy troops and awaited the arrival of the rest of the assault force.

The advance inland was difficult. First Sergeant Pasquale J. Fusco reported, “We could not spot them [Japanese] even with glasses and it made our advance very slow. When we moved forward, it was as a skirmish line, with each man being covered as he rushed forward from cover to cover. That meant that every man spent a large part of his time on the ground.

“While at prone, we carefully studied the trees and ground. If one of our men began to fire rapidly into a tree or ground location, we knew that he had spotted a sniper, and those who could see the tree took up the fire. When we saw no enemy, we fired occasional shots into trees that looked likely.” It would be precisely this type of advance that would later bring considerable criticism upon the 27th Infantry Division.

In the advance, one pillbox gave 3rd Platoon, Company F, difficulty. The enemy halted the platoon’s advance for over two hours, killing eight and wounding six. Captain Wayne C. Sikes, a tank officer, was sent up by Colonel McDonough to see what the problem was. He led his tanks on foot into the enemy fire, joined by the infantry.

But the pillbox was strongly constructed and built into what little high ground existed on Makin Island. Hand grenades failed, as did a flamethrower. Even 75mm armor-piercing shells fired by the tanks did not penetrate the pillbox.

Then, a demolition squad of engineers from Company C, 102nd Engineer (Combat) Battalion under 1st Lt. Thomas B. Palliser appeared. In a combined operation, one of the very few conducted on Makin Island, the infantry, tankers, and engineers managed to get a pole charge of TNT into the pillbox and explode it. Even that did not destroy the emplacement, but the shock of the blast did kill the dozen enemy soldiers inside, ending the contest.

The most common Japanese defense on Makin Island was a hole in the ground. This was no ordinary hole, however. It usually consisted of an open pit for a machine gun, a covered shelter, and a communications trench, all cleverly hidden in jungle foliage. The walls were usually from three to five feet thick and the trenches four feet deep. These were generally connected to a very strong dugout, revetted with sandbags and logs, with an underground exit.

The GIs developed a method of attack against these defenses. A squad of eight men would crawl to within 15 yards and then surround the pit behind cover. The Browning Automatic Rifleman (BAR) and assistant would provide cover fire while two others with grenades would attack on each flank of the pit. They would rush the enemy post and toss their grenades and then dash to the opposite side dropping more grenades. Once the grenades had exploded, the others would follow with bayonets, some covering and others inspecting the pit. According to one participant, “We did not lose a man in this type of action.”

Colonel Kelley expected the main enemy defenses to come at the west tank barrier. He joined with the attacking troops to supervise what he expected to be the major battle for the island.

Assisted by two Washington observers—Marine Lt. Col. James Roosevelt (the president’s eldest son) and Colonel Clark Ruffner—Colonel Kelley moved forward to observe but came under heavy fire from enemy machine guns, probably those in the bombed hulks in the lagoon.

Under orders from division headquarters to “Continue your attack vigorously to effect a junction with McDonough without delay,” Kelley ordered the attack resumed. Company B was on the right and closest to the tank barrier while, off to the east, firing from Company F and some tanks could be heard. Soon, both companies were being fired at by the other across the barrier. For safety reasons, Company B took cover.

Company C, meanwhile, was farther from the barrier and making slower progress against stronger opposition until halted about 250 yards from the barrier. Using the cover of swampy gullies, small pools, high grass, and large trees, the Japanese had set up machine guns in a well-concealed culvert. The fire was strong, well-directed, and its source completely hidden from view at all but inches distance.

In their advance, a platoon of Company C had been pinned down by this fire in a small clearing along the road. As the infantrymen pondered their next move, 2nd Lt. Daniel T. Nunnery, sheltering nearby, observed Colonel Kelley coming forward again. Using hand signals, Lieutenant Nunnery tried to warn the colonel of the hidden danger.

While Colonel Kelley was trying to determine the strength and position of the enemy, he was joined by the regimental commander, Colonel Gardiner Conroy. Initially, Conroy believed that the opposition consisted of only a few snipers, but was convinced by Colonel Kelley that there was strong opposition facing Company C. He decided to bring up some light tanks to feel out the enemy position and determine its real strength.

While Colonel Conroy returned for the tanks, Colonel Kelley moved up to Lieutenant Nunnery’s position, only to find him dead. Another man lay wounded nearby and the regimental chaplain, seeking to assist the wounded man, was himself shot in the arm. Another man was killed, and seven others wounded in the brief time since Colonel Kelley had arrived.

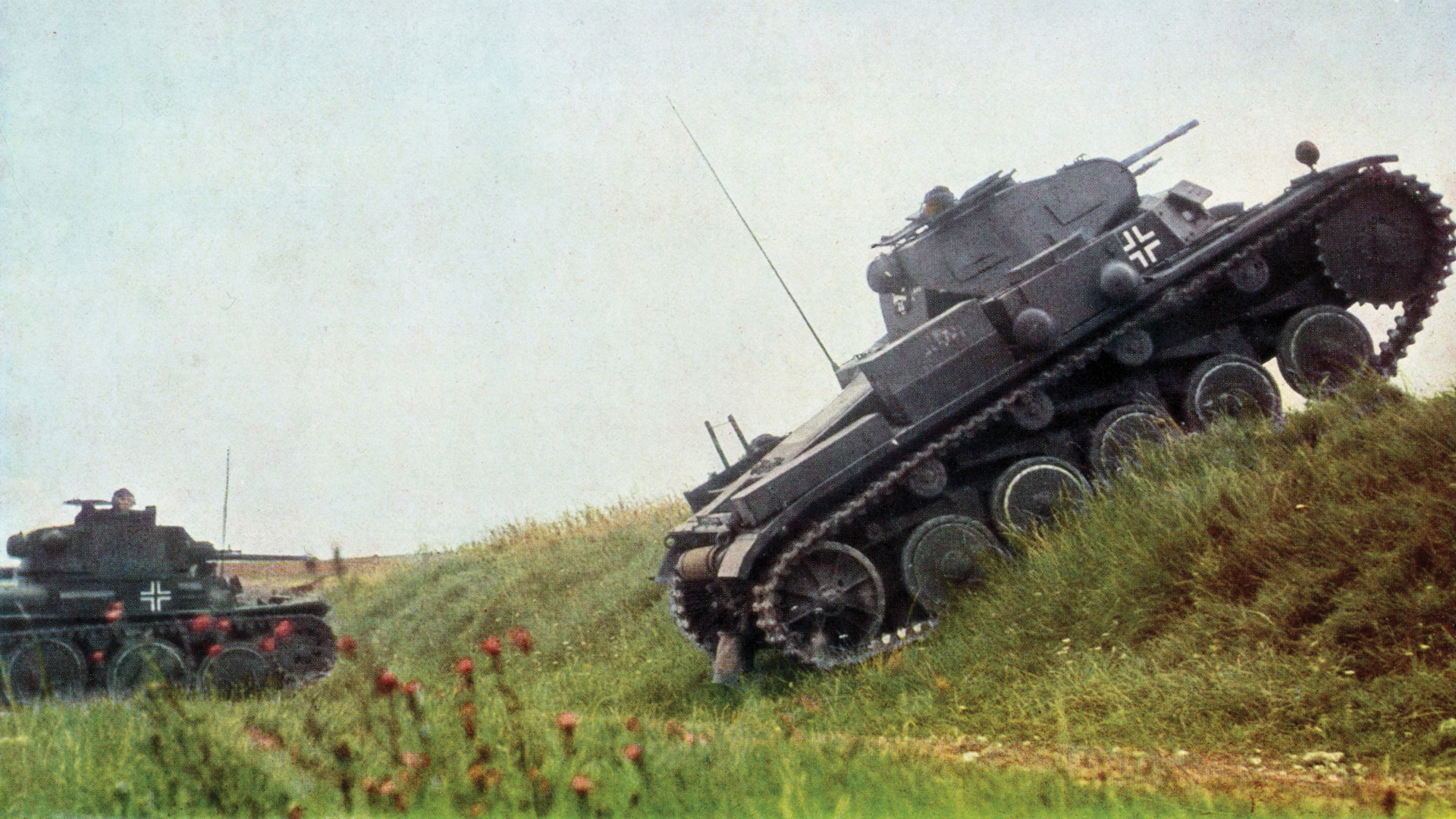

Four light tanks of the 193rd Tank Battalion then appeared. Behind them walked Colonel Conroy, upright and without seeking cover. He was shouting directions for the infantry to get moving and join the tanks against what he obviously believed was negligible opposition. Colonel Kelley shouted to him to seek cover, and that the opposition was both strong and accurate.

Just as it seemed Conroy would heed Kelley’s warnings, he was shot between the eyes and crumpled to the ground. The 165th Infantry Regiment had lost its commander to enemy fire in mid-afternoon of November 20, 1943.

Shocked, both Colonels Roosevelt and Ruffner, accompanying Colonel Conroy, attempted to carry his body to safety but were directed by Colonel Kelley to leave his body and save themselves.

The light tanks, which never fired a shot, retired to the rear. All this shouting and directions emanating from behind Colonel Kelley’s tree brought him the unwanted attention of the Japanese, who turned their machine guns on him. Colonel Kelley assumed command of the 165th Infantry Regiment, while his executive officer, Major James H. Maloney, took command of the 1st Battalion.

The problem remained Colonel Kelley’s, however. He had no armor, could not use mortars or grenades because of the trapped platoon being in the way, and had no other support available. He ordered 1st Lt. Warren T. Lindquist, with 10 men of his Regimental Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon, to attack the enemy while the rest of the battalion withdrew to better positions and consolidated.

The reconnaissance troops located the enemy gun and tossed two grenades at it but could not see what happened. They then moved against a second gun but were pushed back by “friendly fire” from Company C. After pulling the wounded chaplain to safety, they had to spend the night guarding him since no evacuation was possible in the darkness.

Despite these situations, the first day’s plan for Butaritari Island, the main island of Makin Atoll, had been accomplished. The entire western half of the island, except for the small enclave at the west tank barrier clearing, had been seized. Upon orders from the division headquarters, hostilities ceased for the night.

Meanwhile, Colonel McDonough’s 2nd Battalion had reached the west tank barrier and contacted the rest of the 165th Infantry Regiment. It had cleared the lagoon side of the island and reduced nearly all the enemy installations there, including the radio station, warehouses, and buildings.

Two enemy Type 94 “tankettes” had been knocked out. As night fell on November 20, 1943, the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 165th Infantry, held the front lines while the 3rd Battalion was in reserve. The 105th Field Artillery Battalion was ashore in support, as were the air defense battalions, supporting engineers, medical services, and shore party groups.

So confident was General Ralph Smith that he ordered the 3rd Battalion to Kuma Island the next morning, an order disapproved of by Admiral Turner and General Holland Smith, who felt it was necessary to retain one battalion in readiness for aiding the Marines at Tarawa.

The 27th Division settled down for the night. The landing craft and tanks assembled behind the lines, as did the reserve battalion. At the beaches, logistics were a problem, for moving the supplies and ammunition was becoming increasingly difficult as the troops advanced further inland.

Even as these issues were addressed, the Japanese created others. Several Japanese had managed to avoid the advance and survive in the western half of Makin. These now tried to rejoin their comrades to the east, and in doing so they aroused the fears of all soldiers lying alone in a dark night. The result was several casualties and a sleepless night for the infantry.

Using English phrases they had picked up, or suddenly throwing grenades out of the complete darkness, they kept the GIs on their sharpest alert the entire night. Even firecrackers were used. One Japanese soldier crawled to the edge of a GI’s foxhole and announced, “Me got no gun” before he was shot and killed. His weapon was found beside him in the morning.

Two new Japanese machine guns suddenly appeared in the lagoon; five others were placed near King’s Wharf. Another suddenly appeared in a wrecked enemy reconnaissance plane in the lagoon. A group of 16 Japanese tried to infiltrate past Company E’s flank near the lagoon. After spending the night sniping, they lay hidden in the tall grass but were discovered and eliminated in the morning. Enemy snipers even reached back into the tank park, killing three men who had left the safety of their tanks.

The morning brought solutions to these problems. Tanks moved to the lagoon’s edge and shelled the hulks, the wrecked plane, and patrol boat. Air strikes soon followed. Next, the enemy “pocket” at the west tank barrier was addressed. S/Sgt. Emanuel F. De Fabees led a patrol into the area and in some unrecorded fashion eliminated the pocket’s defenders.

In another instance, three light tanks cleared opposition in front of Company F by carefully firing canister rounds into the enemy’s suspected area. Yet, sniper fire would continue to be the main source of enemy resistance for the day.

Company E had received the assignment of clearing up the western half of the island while the 1st Battalion cleared the west tank barrier. This latter attack was delayed for two hours while the tanks refueled. Then, despite calls for it to stop, the air bombardment of the area continued, delaying the attack further. The attack, led by 10 medium tanks, did not begin until 11 a.m.

At that same time, the Marines and 2nd Platoon, Company G, returned from searching the outlying islands and were attached to Colonel McDonough, who ordered them to join in his battalion’s attack.

The attack included Special Detachment Z, Company G, and Company E. Behind them came a second line with more of Companies E and G, and the Marine platoon. Averaging three yards a minute, the line advanced aggressively.

“On the second day we did not allow sniper fire to deter us,” said 1st/Sgt. Thomas E. Valentine of Company E. “We had already found that the snipers were used more as a nuisance than an obstacle. They would fire, but we noted little effect by way of casualties. We learned that by taking careful cover and moving rapidly from one concealment to another, we could minimize the sniper threat.

“Moreover, we knew that our reserves would get them if we did not. So we contented ourselves with firing at a tree when we thought a shot had come from it and we continued to move on. Our reserves could check on whether we had killed him or not.”

The dual-purpose 3-inch guns were eventually abandoned as the enemy fled to the eastern tip of the island. The GIs faced only pillboxes, dugouts, and log-revetted emplacements. Some of these were defended, others not. The grenade, BAR, machine gun and tank were the main weapons used as the advance moved east. As another night approached, the Americans settled down once again for a second night on Makin Island.

Expecting a repeat of the night before, they were not to be disappointed. Sniper fire, grenades, and some mortar fire were received, but nothing unusual or unexpected. At daylight, the 3rd Battalion again moved forward, supported by aircraft from the USS Coral Sea and USS Corregidor. The USS Liscome Bay provided anti-submarine patrols, as there had been some scares recently. The east tank barrier was shelled, and the advance resumed against light opposition.

Earlier intelligence had identified many enemy positions, and these were now targeted by supporting arms. Captain Lawrence O’Brien and his Company A boarded landing craft and sailed three miles behind enemy lines. They landed unopposed, killed 45 enemy soldiers, and established themselves on the Japanese rear.

Another flanking operation, this one under the command of Major Brandt, also succeeded and began moving towards the 3rd Battalion. That afternoon Gen. Ralph Smith officially assumed full command of the forces on the island, as planned. Later he received orders to re-embark the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 165th Infantry, from Admiral Turner; Colonel Hart’s 3rd Battalion would finish the mopping up.

But before these operations could be completed came “Saki Night.” The night of November 22-23 saw the 27th Infantry Division beginning to board ship for a return to Hawaii. Enemy resistance was considered weak and disorganized. Only 5,000 yards of Butaritari remained unoccupied. During the day, 100 enemy soldiers were killed and another 99 captured. Clearly the battle was over.

Admiral Turner even officially announced that Makin Island was secured, “though with minor resistance remaining.” Apparently even the Japanese thought so. Delving into their supplies of liquor, they prepared for their end. Gathering a group of natives, they pushed them ahead of their attacking force as soon as darkness fell.

After the natives had passed the American lines, the Japanese followed, imitating the cries of a baby to get as close as possible before being discovered. But they were recognized and a fight began, with American machine guns, BARs and rifles ripping into the enemy group. More and more enemy troops appeared. Some still carried liquor bottles or glasses filled with saki. Several jumped into GI foxholes and fought to the death. Others used clubs as weapons. Grenades sailed through the night. Wounded GIs held onto their weapons, knowing this was a fight to the death. Only daylight brought relief.

“Saki Night” cost the 165th Infantry three dead and 25 wounded; over 50 Japanese dead were counted.

Day four of the operation cleared the last 500 yards of Butaritari. The battle was over. All told, it cost the U.S. Army 58 killed in action, 150 wounded, and eight died of wounds. Another 35 were injured in non-combat incidents.

But that was not the whole story. The USS Liscome Bay was torpedoed and sunk while supporting the operation, at a cost of 702 killed, including Rear Adm. Henry Mullinix and Pearl Harbor Navy Cross recipient, Ship’s Cook Doris “Dorie” Miller.

There were 257 survivors injured, burned, or suffering from numerous other ailments. Another seven sailors were killed and 18 wounded supporting the campaign. A turret fire aboard the USS Mississippi (BB-41) killed 40 and injured nine. Even the submarine USS Plunger (SS-179) on pilot rescue duty was strafed by an enemy plane and suffered six wounded.

General Ralph Smith signaled “Makin Taken,” signifying the combat was over, but the fighting had really just begun. Both the U.S. Navy and certain U.S. Marine Corps officers were highly critical of the Army’s performance on Makin.

The Navy was particularly critical of the time it took to secure the island, time in which its ships had been tied to supporting the ground troops and exposed to enemy attack. Proof was readily available in the loss of the USS Liscome Bay and the resultant casualties.

As for General Holland Smith, he was clearly superfluous as a corps commander of two units fighting separate battles over 100 miles apart. Tied by naval transportation to Makin, he yearned with his entire being to be present at Tarawa where “his” Marines were undergoing one of the most horrendous battles of the war.

This he blamed on the slow progress of General Ralph Smith’s division. He claimed that a few snipers had held up an entire battalion for four hours; that Army tanks refused to assist the infantry, causing Colonel Conroy’s death; that the wild firing by the GIs on the first night indicated a lack of discipline among them; and that they unnecessarily delayed the attack on the morning of the second day, losing four hours of combat time and thereby extending the battle.

He would not forget this, and the following year when the 27th Infantry Division was again under his command at Saipan, he would relieve Ralph Smith of command, thus igniting an inter-service dispute that would last for decades.

None of this should obscure the fact that the 165th Infantry Regimental Combat Team did take Makin Island in a military manner. For the GIs, whose training as we have seen was inadequate to say the least, they had learned as they went. Comparing the statements of Sergeant Fusco on the first day with that of Sergeant Valentine a day later indicates a marked difference not only in tactics, but in attitude.

So, too, does the actions of Captain Sikes in organizing an ad hoc combined arms team to eliminate an enemy position which had halted the infantry alone. Considering all the obstacles placed in their path, the GIs of the “Fighting 69th” served their forefathers well.

Nathan Prefer is the author of several books of World War II history and is a frequent contributor to WWII Quarterly. He lives in Fort Myers, Florida.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments