By Brooke. C Stoddard

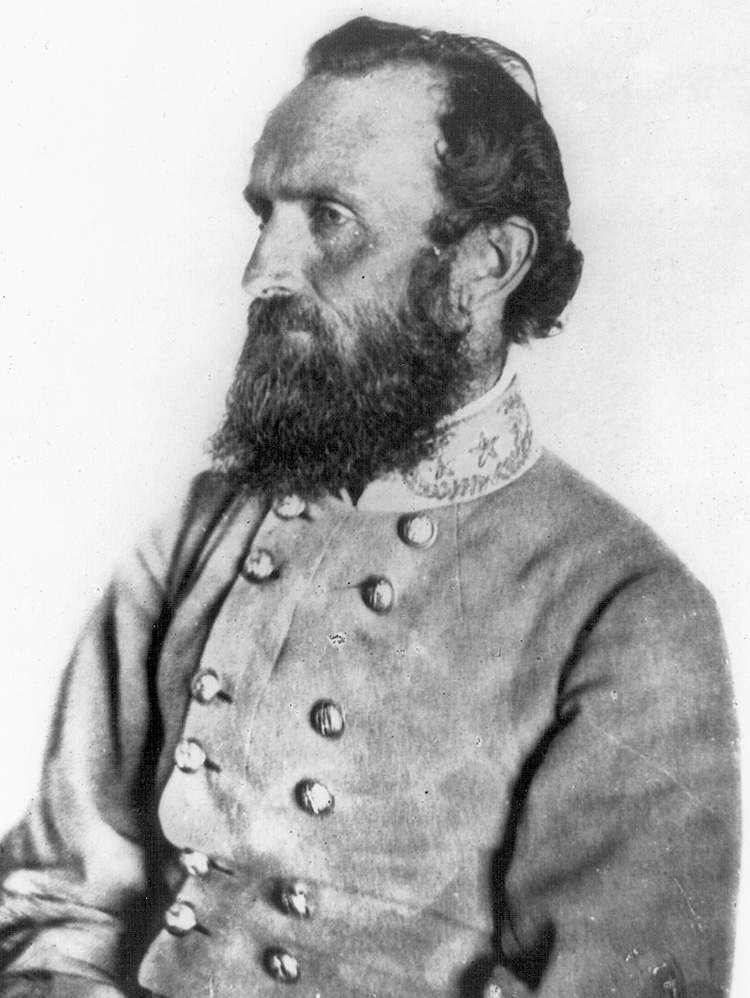

Arguably the most celebrated campaign feat of arms of the American Civil War is that of Stonewall Jackson in the Shenandoah Valley in May and early June 1862. Others might vie for honors: Grant’s risky marches and battles to invest Vicksburg from the east; Sherman’s dislodging of Johnston down the Western & Atlantic Railroad to Atlanta in 1864. These and others have their adherents, but Jackson’s accomplishment remains an acme. He was surrounded by larger armies, but at every point of attack he possessed numerical superiority; he used geography superbly; and he exceeded almost beyond hopes the strategic aspirations of his commanding officer and national president.

Jackson was by turns crafty and lucky. Most of his Shenandoah Valley campaign was improvised; his genius was in devising shrewd solutions to shifting problems. He made mistakes, but he learned from them, and if he did not put the lessons he learned to use in the valley, then he did so during the year that remained to his life. The chief brilliance of his spring valley campaign was that he saw inaction and the status quo as defeat. He would not accept the situation as it presented itself. He had to change it, and radically. In this, he was like Grant across the river from Vicksburg, or Lee behind fortifications at Richmond in June 1862. The prevailing condition would only lead to frontal assaults, great loss of life, and no guarantee of success. The remedy was movement, to win battles not by the breasts of men presented in line of battle but by marching feet. And like Grant and Lee in their own situations, Jackson was faced by commanders who expected their opponent to accept the prevailing condition, who were not expecting movement, or at least of the radical kind Jackson—or Grant and Lee—set into motion.

No one can now “get into” or discern Jackson’s mind. For that matter, no one really could in 1862 either and not a few observers, including many of his footsoldiers and some immediate subordinates, thought he might literally be insane. Certainly he was odd, and extremely secretive about his plans. But he could understand like no one else—with the exception of Robert E. Lee—the battleground of Virginia as a whole and how one part was not disconnected from the others, but instead strategically linked. He could see the Shenandoah Valley as a whole and how the varying military units in and near it were not isolated forces but rather more like pieces on a chessboard, each not only holding its own power but gaining or losing power depending on its position and all having an overall power depending on their positions taken together.

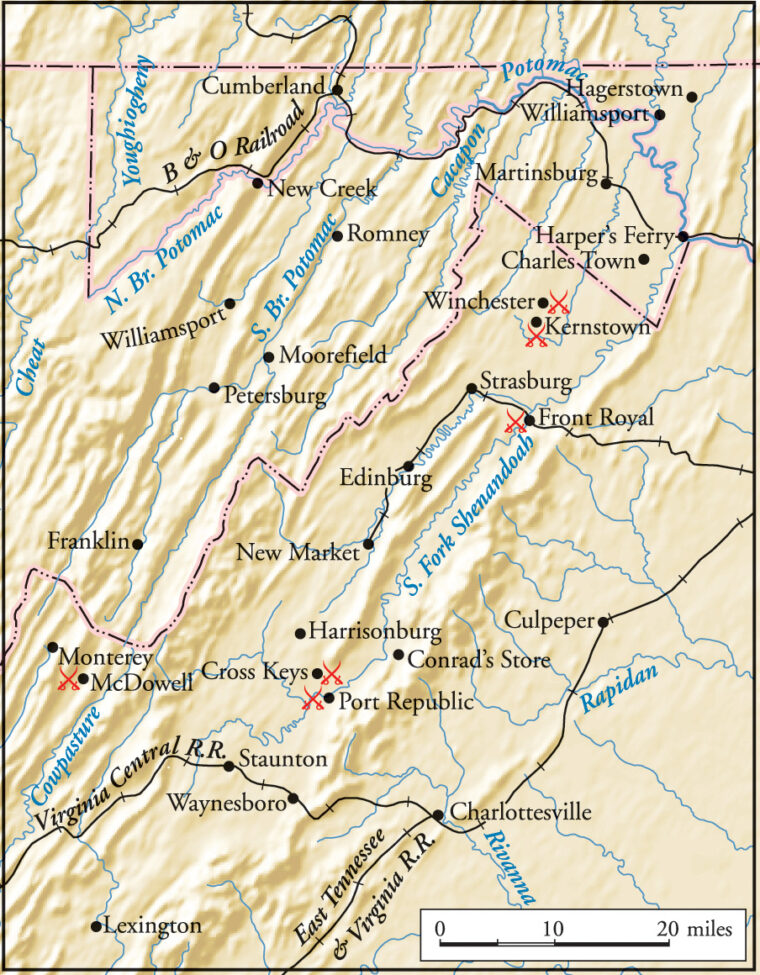

Indeed, no other field in the American Civil War lends itself more to the analogy of chess than the valley in the spring of 1862. The valley is the chessboard and the various Confederate and Union armies the opposing pieces. This valley has different definitions, but for our purposes it stretches from Staunton in the south to Williamsport and Harper’s Ferry in the north, a total of 120 miles. Jackson’s valley campaign was a campaign of distances. The distance from Winchester to Strasburg is 18 miles, from Strasburg to New Market, 30 miles. Even more important, Washington, DC, was 50 miles from Harper’s Ferry.

From Strasburg nearly all the way to Staunton runs 55-mile-long Massanutten Mountain, dividing the valley down the middle into two parallel valleys. The western valley is about 9 miles wide and had much open country by way of farms. It also enjoyed the best road, the Valley Pike. The eastern, or Luray Valley, is about 6 miles wide, was largely wooded and had an inferior road. Only one road traversed Massanutten Mountain, running roughly east-west from New Market to Luray. Massanutten is a key feature on the chessboard. Armies marching up one side might not be detected on the other, and whichever army held the road that passed over its midpoint could control a good many possibilities for movement up and down the valley as a whole (“up” always meaning in the southerly direction owing to the northerly direction of the flow of the Shenandoah River). Conceivably, a Federal force could be marching up the western valley while a Confederate one marched down the Luray Valley to seize Front Royal.

But the Luray Valley could also be a trap. A strong Federal presence in Front Royal matched with Federals at the Massanutten crossing would require that a Confederate force abandon the Luray Valley by way of any of several gaps (from north to south—Thorton’s, Fisher’s, Swift Run, Brown’s, and Rockfish) over the Blue Ridge and into the Piedmont area of Virginia, or remain bottled up in the southern Luray Valley, or retreat farther south.

Several other points need to be made in advance of a discussion of Jackson’s valley campaign. One is cavalry. Jackson was fortunate to have men who not only loved to ride but who did it very well and, even more important, knew the valley as well as the backs of their horses’ heads. The Federal cavalry was not nearly so good and had the disadvantage of being on foreign ground. Jackson’s cavalry under the dashing, often brilliant, sometimes irresponsible Turner Ashby could hold an effective screen in front of the Union armies, keeping them nearly blind to any movement of the Confederate infantry beyond the riders. Several times Jackson’s army “disappeared” so far as Union commanders could discern, an extremely dangerous state of affairs for them.

And, of course, Jackson was working “on his own ground.” He had been a professor of natural and experimental philosophy and of artillery tactics at the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, up the valley 35 miles from Staunton. He knew the territory, and he could rely on a populace working on his behalf and against those of the “invaders.” They would tell him of Federal movements while, if discoursing to Federals at all, disguising those of Jackson. These Jackson all put to his advantage.

One other point. Jackson in late March called to his tent Jedediah Hotchkiss, a 34-year-old teacher and transplanted Connecticut Yankee with a penchant for mapmaking. He asked Hotchkiss to make a detailed map of the whole valley from Lexington to Harper’s Ferry, which Hotchkiss then commenced. Hotchkiss drew as much of the valley as he could, including topography, roads, railroads, buildings, rivers, bridges, and fords. The work of this mapmaker was invaluable to Jackson for the next six weeks.

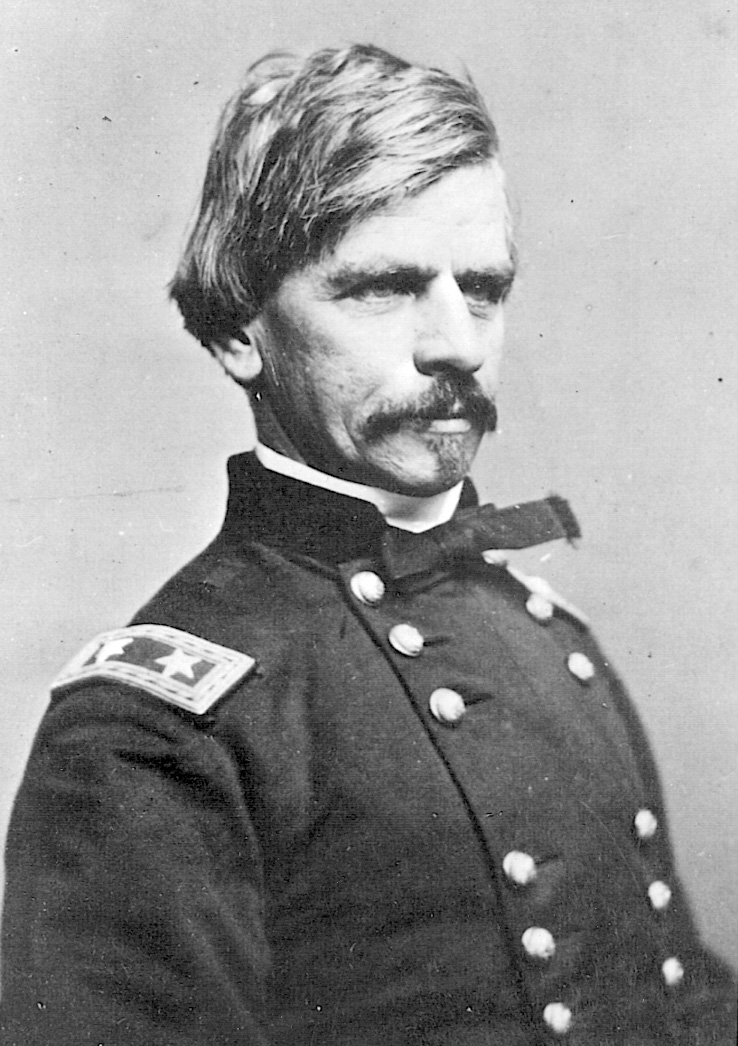

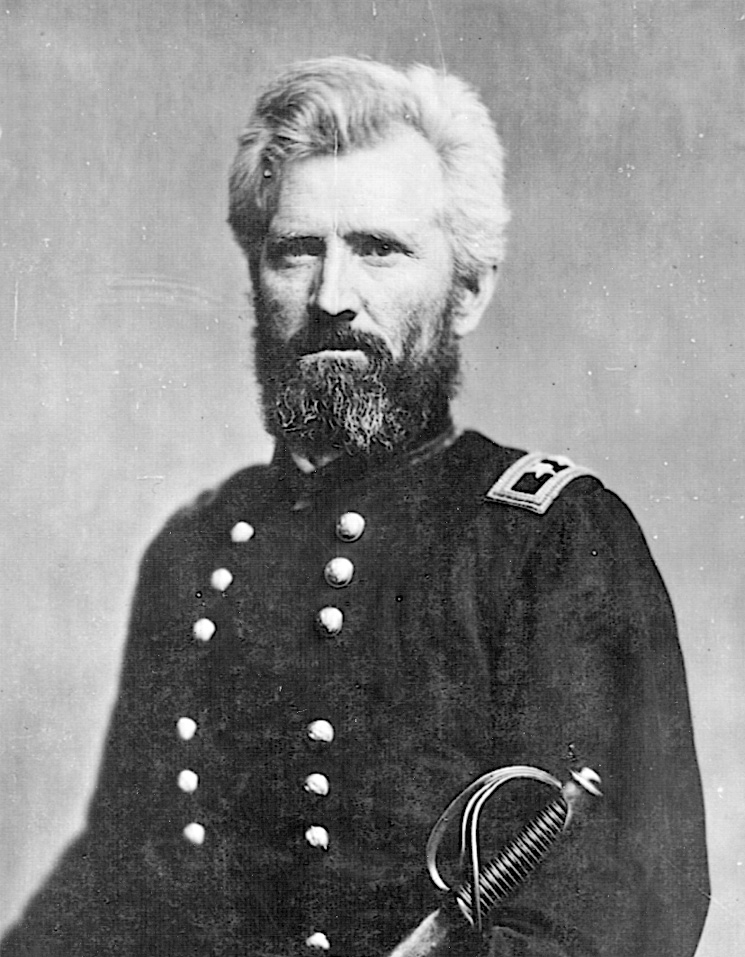

On April 17 as the roads were drying, this is what Jackson faced. His valley army (in all Jackson commanded about 6,000 men at this time, including Ashby’s cavalry) was between Mount Jackson and New Market. Union Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks’ army of 21,000 was also on the Valley Pike threatening him from the north. West of the Shenandoah Valley, strung out parallel to the upper valley and with the vanguard under Brig. Gen. Robert Milroy at McDowell (about 27 miles west of Staunton) was the 17,000-man army of Maj. Gen. John Charles Fremont. He was opposed by 2,500 Confederates under Brig. Gen. Edward Johnson. If Johnson were defeated by Fremont, then Fremont could enter the valley via McDowell and be in Jackson’s rear. To the east, Union General Irving McDowell (of First Manassas infamy and not to be confused with the aforementioned town) was at Fredericksburg with 30,000 men. Confederate Maj. Gen. Richard Ewell was just outside the valley on the eastern side of the Blue Ridge with 8,500 men. Thus within or close to the valley were about 68,000 Federals matched against 17,000 Confederates. In addition, Union Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan (a West Point classmate of Jackson’s who finished far ahead of the Southerner) was threatening Richmond with 100,000 men against 50,000 under Joseph E. Johnston. Robert E. Lee at the time was in Richmond as a military adviser to President Jefferson Davis.

If McDowell were to march overland to Richmond, as was the Federal plan, thus becoming the right flank of McClellan’s host, the fate of Richmond was likely sealed. But Jackson understood that U.S. President Abraham Lincoln was acutely sensitive to the defense of Washington, DC. Should the North’s capital fall to Confederate troops, likely the war would be settled in favor of the South’s secession. If Jackson did not at first know of Lincoln’s—and his Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton’s—sensitivity to Washington’s defense, then he learned of it soon enough after Jackson’s rebuff on March 23 at Kernstown, which lies on the Valley Pike just south of Winchester.

At that place, Jackson made a hasty attack on what he had been told—falsely, owing to a rare intelligence failure by Ashby—was a rear guard of Union troops quitting the valley for McDowell’s command. Jackson had not confirmed the estimate with his own reconnoitering, and his men confronted far more than they had expected. Jackson bloodied the Union force, but then retreated up the Valley Pike past Strasburg. The rebuff, however, had some of the effects of the kind of victory Jackson coveted because it foiled reinforcements moving to McClellan. Lincoln stopped McDowell’s intended advance to Richmond so he could thwart any Confederate move from the west on Washington, and more forces were sent to the valley to deal with Jackson.

Other important lessons were learned at Kernstown and during the weeks before. On March 11, Jackson had called a council of war in preparation for a night attack against Banks when that general was encamped north of Winchester. Jackson’s subordinates objected vociferously owing to the fact that many of the men had marched in the opposite direction to get rations and they would be exhausted if forced to Jackson’s intended point of attack. Jackson was furious. He vowed he would never again hold a council of war with subordinates. He was true to his word and from that time forth he kept his own counsel, telling practically no one of his major plans. In addition, if the point was not already clear, he knew he would have to make sure of an enemy’s strength and to exceed it if possible with greater numbers on his own part.

Deception, secrecy, movement, picking up disparate commands to strike with superior numbers: These were the hallmarks of Jackson’s subsequent campaign in the valley.

On April 17, Banks moved south. Jackson, with less than half the Federal numbers, began to withdraw. Banks seized New Market. Two days later, he sent some Federal troops over Massanutten Mountain to Luray. If Banks had energy and dared much, he could push down both valleys. If he could get down the Luray Valley quickly, he could cut Jackson off from Ewell and then defeat Jackson on the Valley Pike or in the open ground south of Harrisonburg. Jackson saw the danger. He sent his men off in swift marches such that soon they would be known as Jackson’s “foot cavalry.” On the 18th they marched more than 20 miles to Harrisonburg. The next day they marched around the southern rump of Massanutten Mountain to a village called Conrad’s Store, 25 miles south of Luray and near Swift Run Gap, in case they were pressed to leave the valley. In three days they had marched 55 miles and secured their communications with Ewell. Banks marched down to Harrisonburg on the 26th.

Jackson’s new location was a safe one. The Blue Ridge was at his back and he could make a defense of it; moreover, Ewell could reinforce him. And he was checking any move by Banks on Staunton—through which ran the valley’s only rail link to Richmond—because he could attack him in the flank as he marched. Still, the situation was not much use to Johnston in Richmond, and McDowell was again massing forces for a move on the Confederate capital.

Jackson decided to act. He had Ewell march with his 8,500 men across Swift Run Gap to take over the valley army’s camp sites. Ewell’s orders were to watch Banks. Ashby, in fact, had been sent over to the Valley Pike to demonstrate against Banks. But even Ashby did not know Jackson’s true intentions. Ewell knew somewhat more, but not much.

On April 30, Jackson, letting no one know his destination, put his men on a march southwest to Port Republic. The weather was awful and the march was slow. From Port Republic on May 3, Jackson turned east toward Brown’s Gap and marched out of the Shenandoah Valley. Those who saw the move believed that Jackson was in retreat and abandoning Staunton. The soldiers were bewildered; if they were to help the people in Staunton, or to wrestle with Banks, they were going exactly the wrong way. Jackson marched to Mechum’s River Station on the Virginia Central Railroad, loaded his men in rail cars, and had them hauled by rail back into the valley all the way to Staunton.

On the same day that Jackson moved, Banks assured Washington that Jackson had quit the valley and was headed for Richmond. Lincoln and Stanton took the opportunity to remove Shields’ division from Banks and order Banks to retire toward Strasburg, he being weakened by the loss of Shields and there not being much more to do where he was. Shields was to go to McDowell at Fredericksburg and join in his overland march on Richmond.

At noon on May 4, men of the valley army unloaded at the Staunton station. Staunton citizens—who only hours and days before were sending valuables out to the countryside and fearing a Federal occupation—rejoiced at the sight. Jackson ordered that no one leave the town and riders who had left for the west be tracked down and restrained. Then, because he did not like to work himself or his men on the Sabbath—the day they had traveled by train—Jackson gave his men two days of rest as atonement.

Federal Brigadier Milroy, who had been pressing Johnson eastward with his 3,000 men, caught wind of the Confederate reinforcement despite Jackson’s blackout, and retired west again, taking up a position near the town of McDowell. Johnson with his 2,500 men followed and deployed on a hill across the Bull Pasture River as Jackson with about 6,000 men, came up. Milroy did not wait for developments. He attacked on May 8. Johnson was hard-pressed, but Jackson’s men came into the fight and repelled the Federals. It was a sharp struggle and by no means a clear triumph for the Confederates, who actually lost more men than the attacking Unionists.

Nevertheless, Milroy could see that he was outnumbered and retreated the next day. Jackson, no doubt with a hunger to smite the foe utterly in the Old Testament sense, pursued for three days. Perhaps he had in mind to defeat Fremont at Franklin and then get into Banks’ rear from the west. In any event, Jackson ultimately gave up the chase, turning back toward McDowell. He reentered the valley May 16—owing to embracing Johnson’s command, which would now march with the valley army—with more men than he had when he left it for the battle at McDowell. Jackson figured—rightly—that Fremont was out of the picture for the time being, at least not a threat to Staunton.

So Jackson headed up the Valley Pike, soon treading ground recently surrendered by the retiring Banks. He reached New Market on May 20. Johnston in Richmond ordered Ewell to follow Shields out into the Piedmont and Jackson merely to watch Banks. This would have forestalled any offensive against Banks, so Jackson telegraphed Lee in Richmond. Lee telegraphed back that Jackson could keep Ewell and attack Banks.

The Union general was nervously awaiting developments at Strasburg, having established a defensive line south of the town and across the Valley Pike. Banks’ strength was much reduced, down to 8,000 men, having lost Shields and others to the efforts farther east. His mission was to hold the lower valley, hence his defensive line at Strasburg. To protect his left flank, he sent a thousand men over to Front Royal 10 miles east and tried to keep his eye—through the cavalry screen—on Jackson, whom he knew to be on the Valley Pike at New Market.

But not for long. On the 21st, Jackson marched his command across Massanutten to Luray, there picking up Ewell’s infantry. Jackson now had 16,000 men. He was in a position to block Banks should the Federal commander attempt to join General McDowell at Fredericksburg. All day long on May 22 the enlarged valley army marched north. By dark the lead elements were within 10 miles of Front Royal, but no Federals knew it—Banks thought Jackson was still in New Market. The next day, Jackson would strike.

Jackson’s hope was to be so swift and so thorough that the thousand-man garrison at Front Royal could not escape, could not even send for, let alone receive, reinforcements from Banks at Strasburg, 10 miles west.

On the 23rd, Ashby cut the rail line to Strasburg, and thus potential retreat in that direction. Then Jackson moved his infantry toward Front Royal. He directed the van off the main road, which might be defended with artillery, to a road coming in from the flank, then ordered the attack. The Federals were surprised but nevertheless managed to hold for a time two vital bridges and then put up a good resistance north of the town. The issue, however, was not in doubt. Outnumbered 16 to 1, the Federal garrison retreated to north of the North Fork of the Shenandoah River and attempted a stand, which Virginia cavalry broke as the day was closing. Of the 1,000 Federals in Front Royal only 400 escaped, for casualties to Jackson’s command of about 50 Southerners.

Jackson figured that Banks, with 7,000 men, did not have many options. His rail link and communications with Washington through Front Royal were severed. He could attack Jackson, or exit the valley westward to join Fremont, or retire toward Winchester. Jackson figured Banks would retire down the Valley Pike toward Winchester and set his gray columns in motion to attack him as he was strung out.

Banks at first thought Jackson was still in New Market and that only Ewell had struck at Front Royal, but when the true situation revealed itself, he acted promptly. He set his army in motion toward Winchester. When Jackson’s men reached the Valley Pike—at Middletown, five miles north of Strasburg—they saw wagons and artillery strung out, a rare opportunity for onslaught. Indeed, they made havoc on the column, capturing wagons and sending Federals to flight. But as it turned out, this was the rear of Banks’ column; the remainder had gotten away. Much of Ashby’s cavalry broke discipline to loot the rich loads of material they found in the wagons, some even took off to visit “the home folks.” Rich as the rewards of the fight at Middletown were, it could have been far more ruinous for the Federals, and Jackson was furious.

The Northerners put up some skilled resistance in their flight toward Winchester. Nevertheless, Jackson pressed his men hard in pursuit, even through the night. The men were exhausted from their marching and fighting, but still Jackson pressed. “I am obliged to sweat them tonight, that I might save their blood tomorrow,” he told a subordinate who pleaded for a short halt. “The line of hills southwest of Winchester must not be occupied by the enemy’s artillery. My own must be there and in position by daylight.” The men knew nothing of this, only that they were pursuing a crippled army. And if their feet were bleeding, their complaints and suspicions of their leader were dropping away as so many stragglers. The seemingly crazy orders of “Ol’ Jack” might not be the product of a cracked mind after all; he was leading them to victory after victory.

Both Confederates and Federals were positioning before sunrise on the 25th. The Confederates had seized one line of heights south of the town, but Banks’ men held the last ridge and their artillery could still play havoc on advancing graybacks. Jackson commanded the battle west of the pike. On the other side Ewell was coming up on a diagonal road his men had taken from Front Royal.

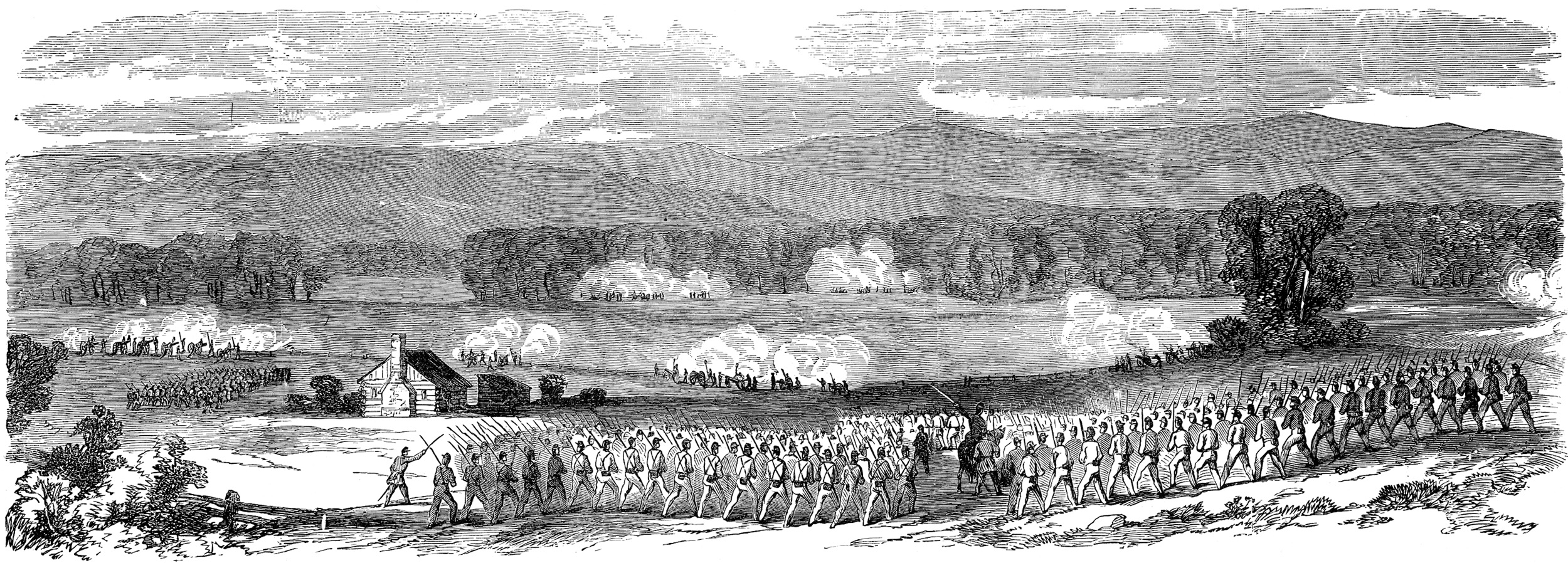

The Federal artillery and supporting infantry were holding well and stalling the Confederate advance. Jackson saw the need to outflank them to the west and sent Brig. Gen. Richard Taylor’s Louisianians to the job. These men formed for the advance and then marched on the Northerners. A Confederate private nearby wrote: “That charge of Taylor’s was the grandest I saw during the war: … every man was in his proper place. There was all the pomp and circumstance of war about it that was always lacking in our charges.” The sun was not yet very high in the sky.

With Ewell pressing the Federal left flank, Taylor the right, and Brig. Gen. Charles Winder with the Stonewall brigade pressing the center, the Federal line collapsed. Union soldiers fell back through Winchester and the Confederates entered to the cheers of the townspeople. It was well nigh a celebration. Jackson was especially revered—the Liberator! But Jackson knew this was no time to rest on laurels; his enemy was in ragged retreat, so fragile it might break to pieces with a concerted blow. He called for Ashby, but Ashby was off chasing prizes of his own. Jackson called for the cavalry under Ewell, but had to wait two hours for two regiments of Virginia cavalry under Brig. Gen. George Steuart

Meanwhile, Banks had made good use of the time, heading for Williams- port where his army could cross the Potomac River, and leaving scores of wagons in his haste. “Never have I seen an opportunity when it was more in the power of cavalry to reap a richer harvest of the fruits of victory,” Jackson lamented. Jackson threw his infantry into the pursuit, but the men had not been fed in two days and had been marching and fighting since Front Royal. They could not maintain the chase, and Jackson finally had to call it off, saving the destruction of Banks for another time.

Still, he had cause for contentment. He had taken his army 177 miles in 17 days and kicked the Federals all the way out of the Shenandoah Valley into Maryland. He had captured, wounded, or killed at least 3,000 of Banks’ command of 8,000 and reaped voluminous supplies in Winchester, more medical supplies, one Rebel officer wrote, than “in the whole Confederacy.” Southern losses since Front Royal were about 400.

This was not, however, the richest fruit of the victories of May 23-25. While Banks was being drubbed, Lincoln and Stanton descended to their deepest pessimism. They were certain that Banks was being driven by a superior force. They were not certain how numerous that force was or where it was headed, but to their eyes it could be a very large one indeed and perhaps set on crossing the Potomac or intent on capturing Washington. Lincoln issued orders to have the Federal government seize the railroads for military purposes, called on Northern governors for more troops, and rescinded a May 17 order to McDowell to march on Richmond in favor of sending some of his troops to the valley.

Once Winchester was secured, Jackson ordered the wealth of captured supplies to begin the trip up the Valley Pike. He also received orders from Richmond, confirming his own convictions, to demonstrate against Harper’s Ferry. He set out with infantry to do so, up the rail line that ran from Winchester to Charles Town and Harper’s Ferry. Through the 27th and 28th, Jackson kept up the demonstration. But by the latter day, Lincoln and Stanton could see Jackson’s thrust for what it was, an understrength threat that could not be made good.

In fact, Jackson was now in danger. He had 13,000 worn troops within a few miles of 7,000 Federals in Harper’s Ferry. Banks was north of the Potomac with 5,000 and being reinforced. Fremont was at Franklin 27 miles west of Harrisonburg with 15,000, and Shields was moving on Front Royal from the east with a division, another division not far behind. Anyone could see that Jackson was surrounded. If Fremont were at Harrisonburg, Banks and Shields could chase Jackson there and crush him in a vise. Fremont, however, declined the march to Harrisonburg—the roads having been blocked by Jackson’s engineers after the fight at McDowell. Instead, Fremont set out through the Alleghenies for the more distant Strasburg. When his superiors at Washington learned this they were furious, but had Fremont continue toward Strasburg in hopes he could still block Jackson’s path. The plan now was for Fremont and Shields to combine at Strasburg and cut off, if not annihilate, the valley army by attacking it from both west and east.

Jackson was told on the 29th that Fremont was en route to Strasburg. He must have surmised the Federal intent to combine Fremont and Shields at that town; still, to all observers he remained exceptionally calm. Perhaps he surmised that communication between Fremont and Shields would be tenuous and a simultaneous conversion on Strasburg difficult. In fact, each might be counted upon to be cautious for fear of being struck by Jackson before a combination could be achieved. Jackson issued his marching orders for a withdrawal and set the valley army in motion toward Strasburg, 45 miles from Charles Town.

The army strung out for more than 10 miles with captured wagons and more than 2,000 Federal prisoners. The Stonewall Brigade, which had closed on Harper’s Ferry, had the farthest to tramp. Rain hampered the march, but all in the valley army could sense that speed was essential to survival. Fortunately for the Confederates, both Fremont and Shields were timid. Shields took Front Royal but remained there while Ord’s division marched toward him from Fredericksburg as reinforcement. Fremont was checked by a demonstration by Ewell just west of Strasburg. So Jackson won the race to Strasburg on the 31st. Then he held the gate open on June 1 for the Stonewall Brigade, which one day marched 42 miles through rain and muddied roads, all without food—one of the most extraordinary such acts during the war.

Jackson had leaped through the jaws of a closing vise, but he was not out of danger. The two forces opposing him were both formidable; he had to continue his retreat up the valley and determine some way of thwarting Federal aims. He had some idea from geography what these would be. Likely, Fremont would pursue up the western valley. Shields would march up the Luray Valley. At Luray, Shields might try to cross Massanutten Mountain to get in Jackson’s rear or combine with Fremont in the pursuit. Failing this, he would likely march to Conrad’s Store and Port Republic, covering exits from the valley into the Piedmont and trapping Jackson in a vise, the other part of which was Fremont, where Massanutten Mountain gave out.

Jackson sent men to burn the bridge at Luray that crossed the South Fork of the Shenandoah. Owing to all the rain, the rivers were high and the loss of the bridge would keep Shields on the east side of it, thus unable to march westward over Massanutten Mountain. Later Jackson would have the bridge at Conrad’s Store burned also, further keeping Shields on the east side of the river and again thwarting any linkup with Fremont. South of the bridge at Conrad’s Store there was only one other, at Port Republic. Up the valley from this town, armies could ford the tributaries and join as they pleased. If Jackson was to keep Fremont and Shields apart, he had to control the bridge at Port Republic; so here he would stop and try to deal with each separately. And at Port Republic he also had an escape route, if need be, out of the valley for the Piedmont.

For several days the valley army marched south up the Valley Pike. Ashby’s men harassed and attacked Fremont’s men to slow their pursuit. In one of these attack’s Ashby was killed leading a charge. For all of Jackson’s consternation with his dashing cavalryman, he sorely missed him.

On June 6 the valley army rounded the southern end of Massanutten Mountain. Jackson had Ewell take up a defensive position just southwest of the hamlet of Cross Keys and placed the bulk of the rest of the valley army overlooking Port Republic. He had won the race with Shields to this place, but barely—a Federal force entered on June 8. These Federals came close to destroying the Port Republic bridge, which crossed the North River, one of two tributaries to the South Fork of the Shenandoah. The other tributary was the South River—Port Republic lies between the two. South River had no bridge, only a ford. Had the Federals destroyed the North River bridge the valley army would have been trapped on the side of the river with Fremont. As it was, Jackson had greater freedom of movement than either Federal army.

About the time that the Federal reconnaissance was being driven out of Port Republic on June 8, Fremont’s army of about 10,000 men attacked Ewell’s 5,000 on a rise outside Cross Keys. Fremont did not make the best use of his forces, and Ewell repulsed them without great trouble. Jackson rode up about the time the fighting was closing. One of Ewell’s brigadiers, 60-year-old Isaac Trimble, who had graduated from West Point two years before Jackson was born, urged Ewell to charge the Federals. But Ewell declined, not wishing to spoil whatever Jackson had in mind for the following day.

Indeed Jackson did have something in mind, formulated after dark on the 8th. He meant to have Trimble demonstrate against the timid Fremont. Ewell meanwhile was to join Jackson’s force west of Port Republic. Together they would cross the solitary bridge into town before dawn and fall upon Shields’ forward elements, commanded by Brig. Gen. Erastus Tyler of Ohio. After the Confederates had drubbed the Federals on this side of the river, they would recross, join Trimble, and whip Fremont. It was unprecedented audacity.

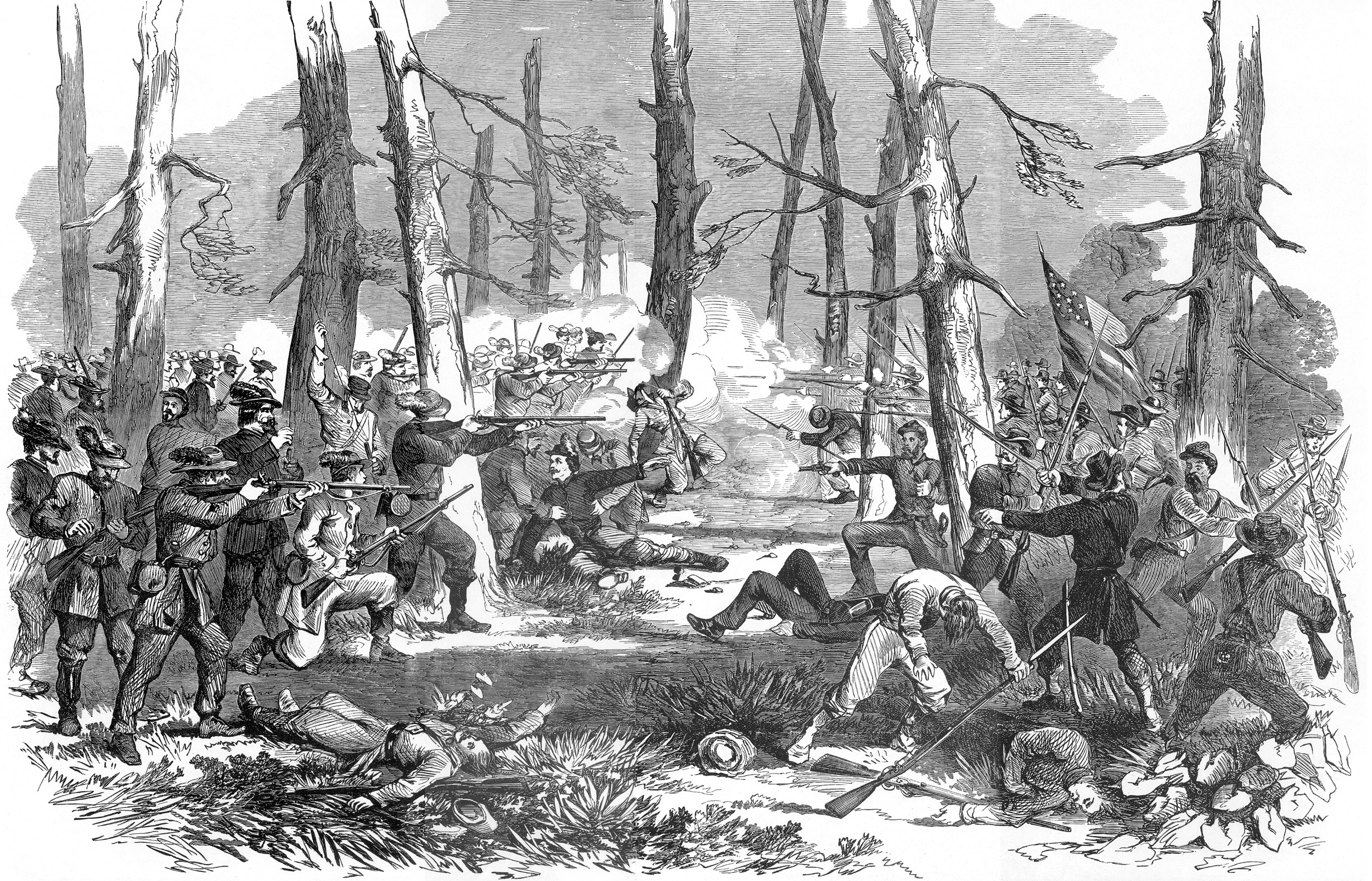

But the morning proved more difficult than Jackson had hoped. The Federals under Tyler were in good position. The Stonewall Brigade under Winder tried advancing across wheat fields only to be cut up by artillery set on a rise at the left of the Union line. Jackson ordered the Federal guns flanked and captured. But Confederates tasked with the job had to traverse deep forest, and then ran into Federal infantry protecting the guns. They attacked but were thrown back.

Meanwhile, reinforcements were slow to get to the field. There was confusion at the Port Republic bridge, compounded by the crossing of the South River via an improvised bridge built in the night; it was beginning to crack up. Jackson had no choice but to throw in more troops as they came up. He eventually ordered Trimble to Port Republic, burning the one good bridge behind him to isolate Fremont, and giving up his idea of going back for a blow at Fremont’s army.

The key to success in the present fight outside Port Republic was the clearing in which the Federals had placed their artillery. Again and again Confederates charged, took it, and were forced back. Ultimately they retained the vital piece of battlefield and Tyler was beaten. He began retreating to Conrad’s Store. Fremont, whom Jackson feared would follow hard on Trimble and at the least make lots of trouble in Jackson’s rear during the fight against Tyler, remained cautious. Later in the day he began a retreat to Harrisonburg and then north of New Market.

As for Jackson, he pursued Fremont, but with less intent to attack than to confuse. He set out all sorts of intelligence that he would again pounce on Federals in the valley. And he gave his men a welcomed rest. They had earned it.

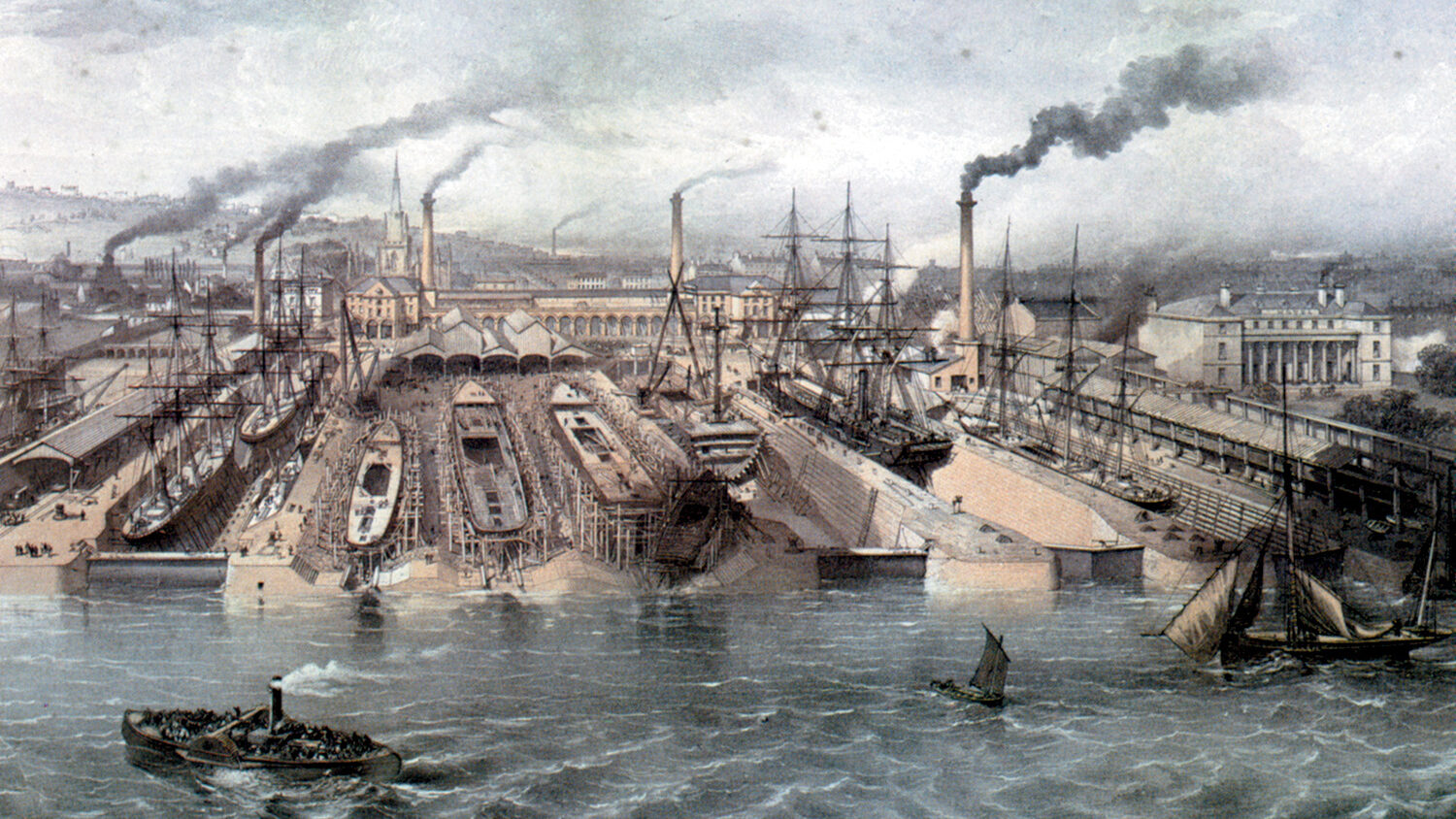

But for Jackson’s dashes and fights throughout the Shenandoah Valley, McDowell would likely have marched on Richmond in May or June 1862, and Richmond might well have fallen. How the seizure of the Confederate capital in 1862 would have affected the war is anyone’s guess, but as events unwound, three more years were needed for the effort. Jackson’s campaign was successful strategically and astonishing tactically because Jackson—with Lee’s support in Richmond—saw the effort not in lines of battle but in lines of movement. Moving skillfully, he could position himself to best advantage and wield his power most effectively. With 17,000 troops he tied up 50,000 Federals and confounded the drive on Richmond.

The man sucked on lemons, told no one of his plans, and passed out religious leaflets on Sundays, but he had a genius for getting results.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments