By Mark Carlson

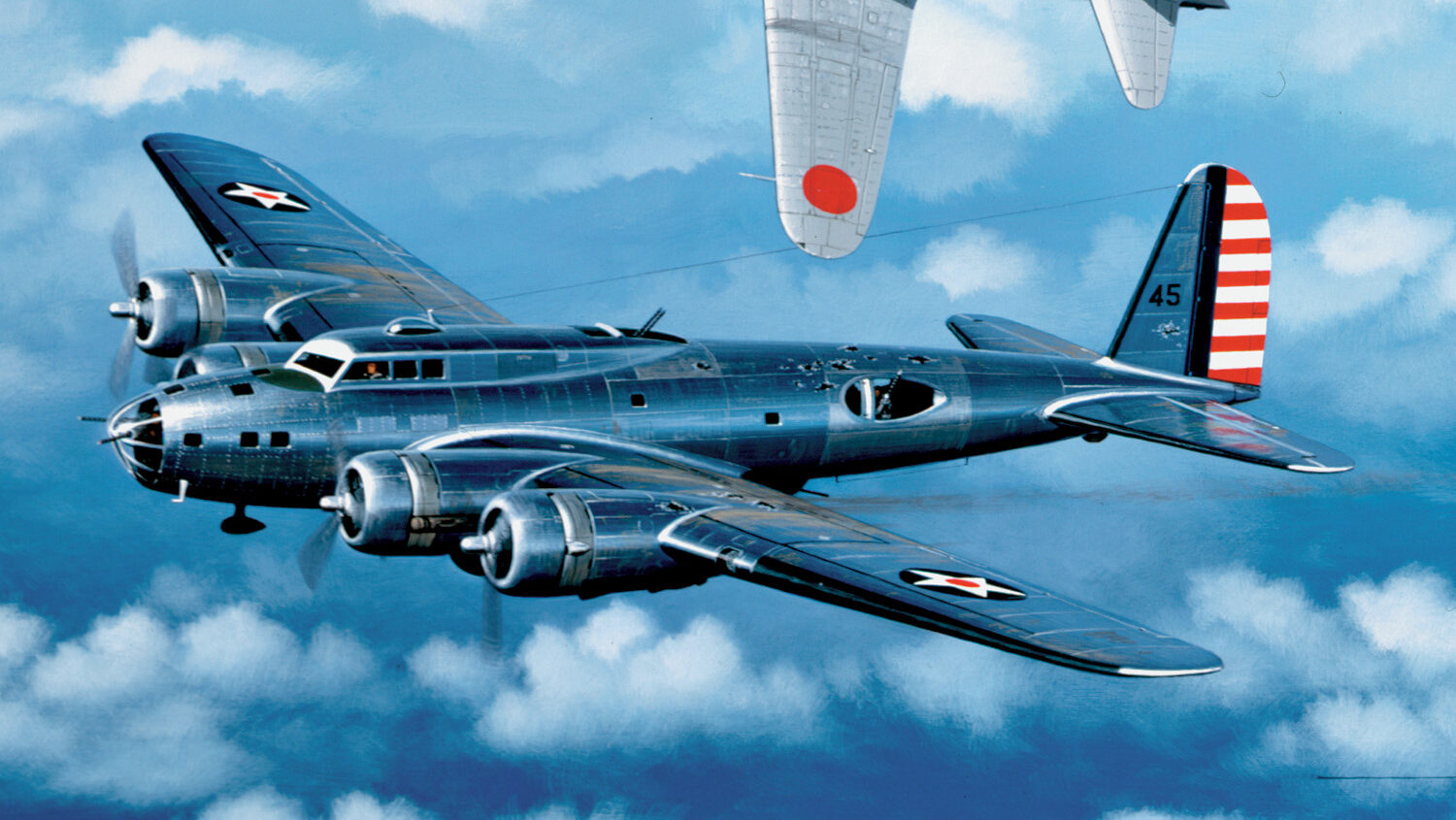

There is no disputing what the North American B-25 Mitchell medium bomber contributed to the Allied victory in World War II. While historians point to the April 1942 Doolittle Raid on Tokyo as the B-25’s shining moment, the raid itself was more a morale booster than anything else.

The B-25 Mitchell was one of the best and most versatile aircraft of World War II. Built in more than a dozen factory and field variants, the 20,000-pound twin-engine bomber earned a reputation for speed, ruggedness, and reliability.

The Mitchell had something that the bigger, more glamorous Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress lacked. Airmen felt a greater intimacy with the compact plane. The powerful roar of the twin Wright R-2600 radial engines roaring to life and driving the bomber down the runway was less heard than felt, more experienced than seen.

Thousands of American men flew nearly 9,900 B-25s during and after the war. Many agree with one thing: the B-25 Mitchell was a fun plane to fly. “It handled more like a sports car than a truck,” said one Fifth Air Force veteran.

General John K. Cannon’s Twelfth Tactical Air Force Mitchells played a crucial role in every major campaign in the Mediterranean from March 1942 to August 1944. The bombers flew from Tobruk, Benghazi, and Corsica, the birthplace of Napoleon.

The versatile B-25s were the scourge of German forces in Tunisia, Crete, Greece, Yugoslavia, Sicily, Italy, and southern France.

Captain Truman Coble, a retired Sears & Roebuck salesman living in Escondido, California, flew 56 missions with the 379th Bomb Squadron, 310th Bomb Group in the Mediterranean Theater. While flying from Tobruk, Libya, and Ghisonaccia, Corsica, Coble and his crew sank three German ships, destroyed dozens of bridges and railroads, and contributed to the eventual Allied victory in Italy and southern France.

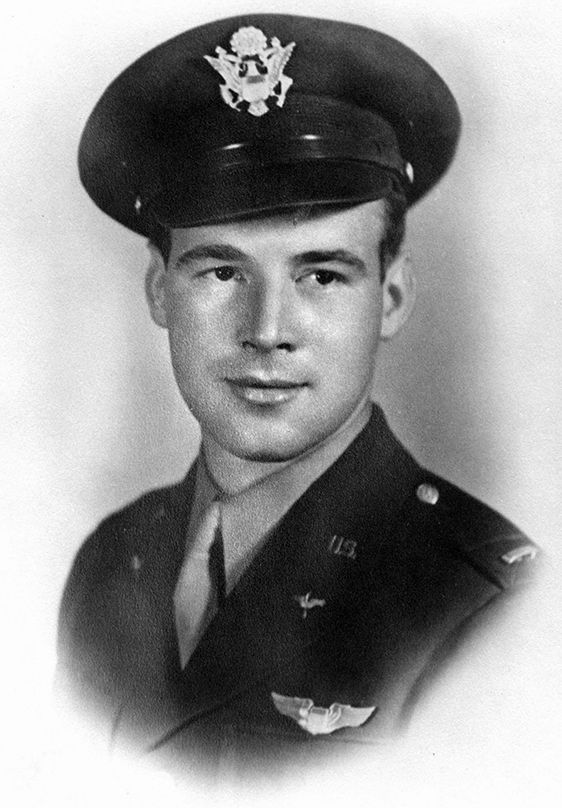

“It was always my ambition to fly in the Air Corps,” said the 91-year-old former Pennsylvania farm boy, who goes by the name “Bud.” “There was this airfield near our farm near New Cumberland and every day around 3:30 a big plane, I think it was a DC-3, would fly in right over us, maybe 500 feet up. I said ‘Man, that’s for me.’ I wrangled my way into the Civilian Pilot Training (CPT) program and learned to fly the Piper J-3 Cub. I had about 40 hours in the Cub.”

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Coble joined the Air Corps and was sent to Santa Ana, California, for basic training. In Oxnard, he went through basic flight training flying Vultee BT-13 Valiants. Advanced training took place in Roswell, New Mexico, where Coble was in Class 43-D and learned to fly the B-25, earning his wings in early 1943.

In Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, Coble was made an instructor, a job he, like most instructors, tolerated with reluctance.

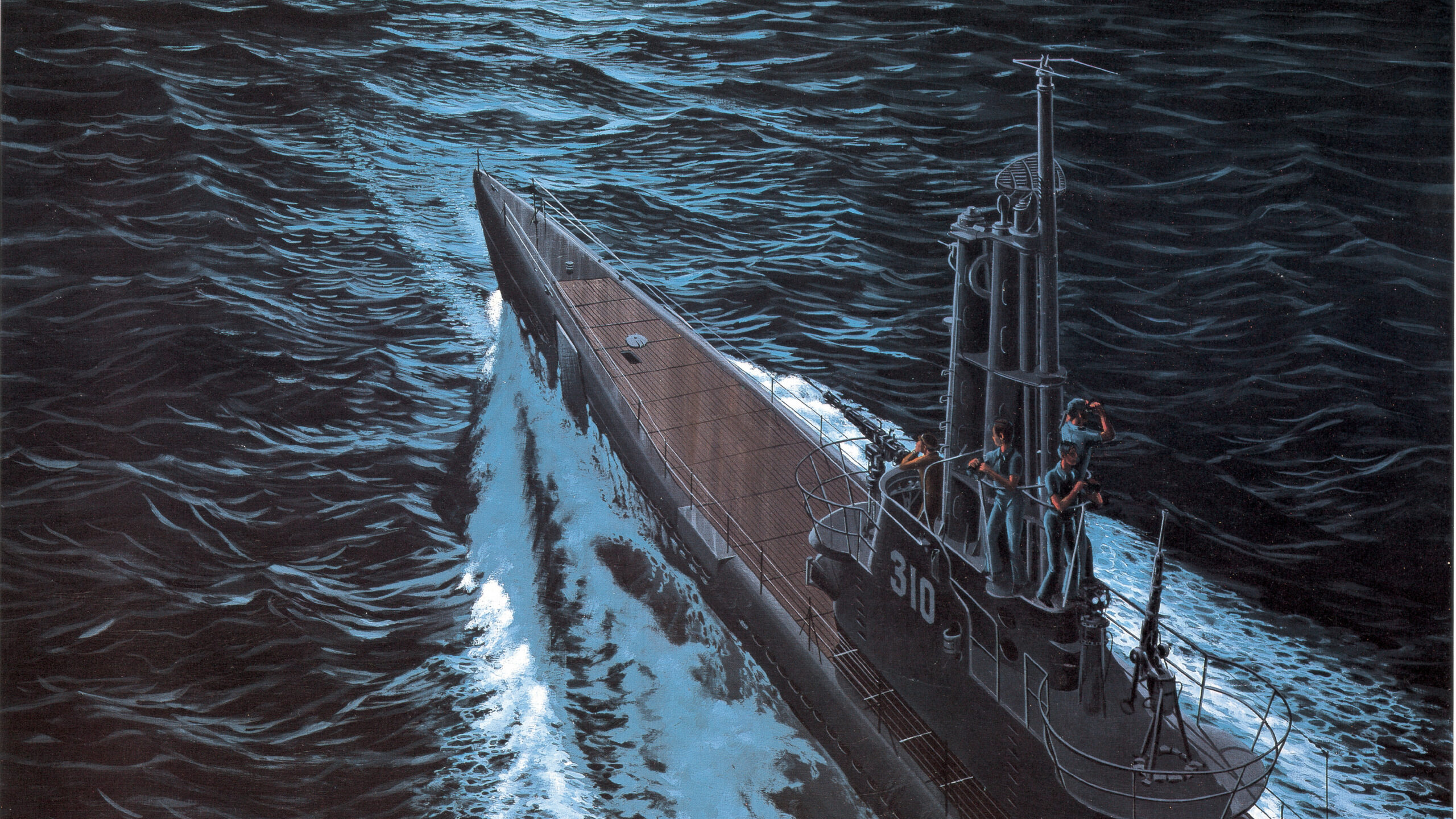

During late 1942 in the Southwest Pacific, Colonel Paul “Pappy” Gunn, head of the Fifth Air Force Service Command, had proven the radical technique of skip bombing to sink ships. As seen at Midway in June 1942, dropping bombs on moving ships from high altitude nearly always resulted in wasted bombs and unnecessary risk.

Gunn theorized that a medium bomber carrying conventional high-explosive bombs could approach a ship at 230 knots at low altitude, that is less than 100 feet, and drop the bombs 500 yards from the target. The bombs “skipped” along the water like thrown stones and hit the ship’s side. It wasn’t always necessary to achieve a direct hit. Even a near-miss from a 500-pound bomb would cause a “water hammer” effect, crushing hull plates.

“I was something of a ‘hotshot,’” Coble smiled. “The Air Force thought I’d be good at teaching the new pilots to skip-bomb at low altitude. We instructors flew around 50 feet off the water. But those students were nuts! They had to be better and flew 30, 25, even 15 feet. It was scary as hell and some planes were lost when they were struck by their own bombs. I went to my C.O. and said, ‘Send me into combat. I want to live!’”

At Greenville, South Carolina, in October 1943, Coble was assigned a brand-new B-25G, T/N 830. “It was painted desert pink and had a big 75mm cannon in the nose. My co-pilot was Lieutenant James Jones. He was a good pilot but a bit of a goof-off. He liked to hit the bars as soon as the engines stopped,” Coble chuckled. “But he did his job. My bombardier was Lieutenant Chuck Irvin. I had a navigator, a flight engineer, and two gunners.”

The proud new owners of No. 830 flew it to Savannah, Georgia, where the combat equipment was fitted. “They put the flexible guns and fixed guns in, armor plate, all that stuff.”

The new plane was christened “Pisonya,” a name chosen by the crew.

Coble and Jones flew the new bomber north to Presque Isle, Maine, then on to Goose Bay, Labrador, and across the Atlantic to Greenland, finally reaching Prestwick, Scotland. After resting they flew south around the French and Spanish coasts and east over the Mediterranean Sea. They and the other new crews joined the 379th Bomb Squadron of the 310th Bomb Group (Medium) of the soon-to-be disbanded Ninth Air Force, based in Libya.

The 310th had been formed in March 1942, and consisted of four squadrons. The 379th, 380th, 381st, and 428th, each with six B-25s. The 310th Group had already supported the campaigns in North Africa and Sicily by the time Coble’s crew arrived in late October 1943. “We first went to Casablanca,” Coble said. “We had some time to get used to the place. We went to the movies. Just a small theater and guess what was playing there? Casablanca!” he laughed.

“The 379th was first based in Tobruk in Libya. It was hot and miserable,” Coble commented. “The temperature went up to 120 degrees in the day. We slept in these tents that never got cool until well after nightfall. Then it went down to near freezing. Bugs and sand got into the food, water, hair and clothes”

Staging out of Tobruk, the B-25s patrolled the eastern Mediterranean and Aegean seas. The Mitchells of the 379th flew tactical missions to bomb German ships and patrol craft trying to support the Axis forces on Crete.

“We worked with the RAF who flew Beaufighters out of Tunisia to hit ships,” Coble explained. “Some missions took off from Philippeville, Algeria, as well. Our armorers had fitted extra guns on the nose.”

Eight Browning .50-caliber machine guns gave the B-25 immense firepower. The Mitchell’s excellent forward visibility made it easy to aim, according to Coble. “It looked like an upside-down Niagara Falls when we triggered all the guns while strafing boats on the water. The plane vibrated like you wouldn’t believe.”

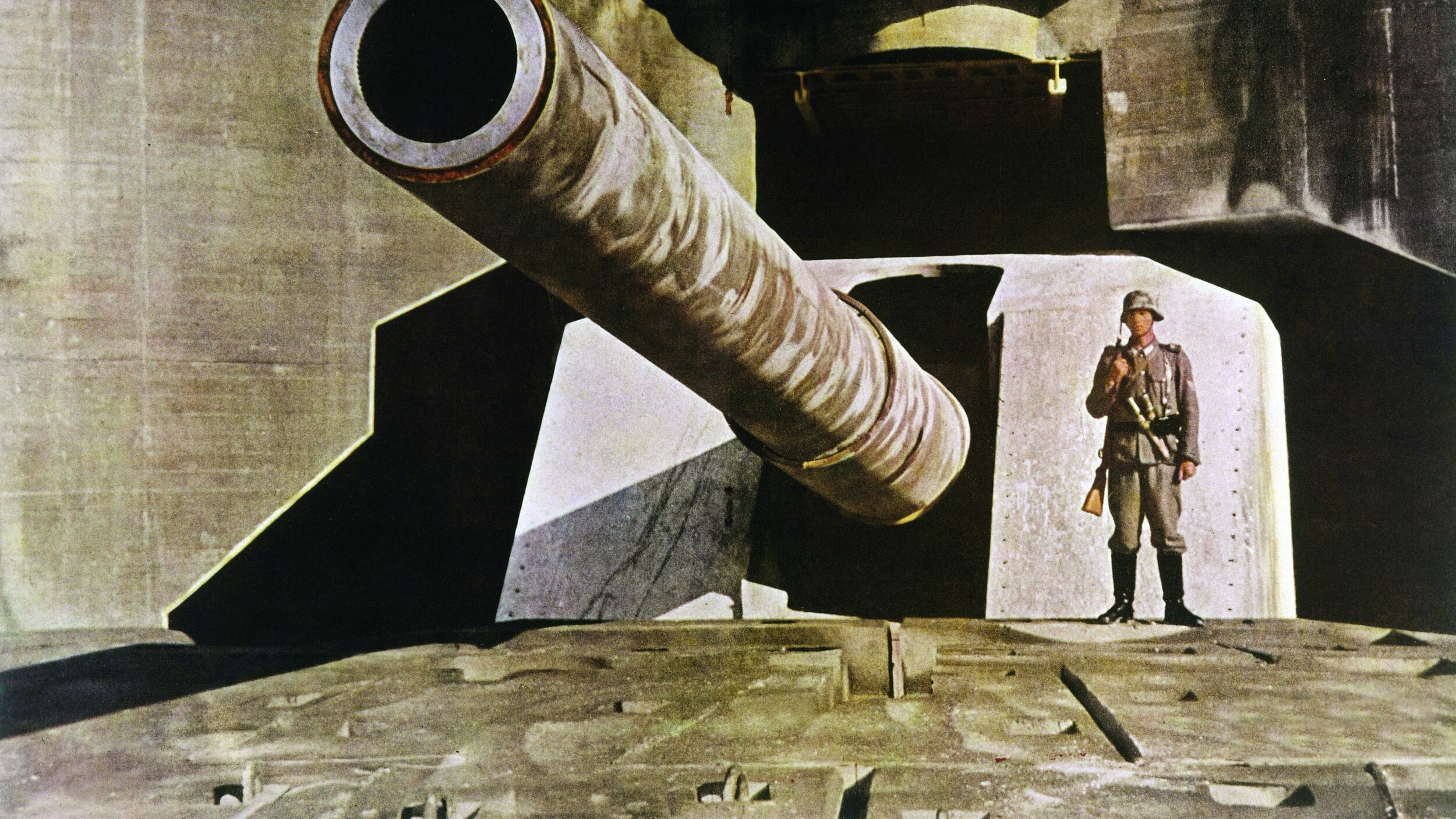

As mentioned, Pisonya carried the granddaddy of all aircraft guns, the powerful 75mm M4 cannon, a derivative of the trusty French 75 of World War I. The American version was also used on the M4 Sherman tank.

Few aspects of the B-25 variants garner more interest than the big gun. A lighter version of the standard M4 with a thinner barrel and modified recoil system was developed for testing in the B-25. It was fitted into the port forward fuselage on the left side of the tunnel into the nose. The muzzle projected from a mild steel fairing.

A February 1944 Popular Science magazine article titled Flying Big Gun stated that North American test pilot Roger Rudd tested the first cannon-armed B-25 off the California coast in November 1942. After several firings, Rudd said it produced a “good healthy jolt.” Further tests led North American to conclude the B-25 “could take that and plenty more.” The article went on to say the first use of the gun in combat “destroyed a Japanese transport as it was unloading, ending the earthly worries of fifteen Japs.”

Five well-placed shots from another B-25 slammed into a Japanese destroyer, causing great damage. A second run on the ship set off internal explosions.

There was no doubt that with high-explosive shells and a muzzle velocity of nearly 2,000 feet per second, the 75mm cannon was capable of doing great damage to enemy vessels or ground installations.

Firing the gun did have an effect on the airframe, however. Research at the San Diego Air & Space Museum revealed accounts that the airspeed dropped by as much as 20 knots from the recoil. Some airmen swore the plane actually stopped for an instant, but this was a physical impossibility.

The cannon was bore-sighted and fired by the pilot with the N-6A gun sight mounted on the top of the instrument panel. It was a more common practice to use the .50-caliber tracers to aim the plane at the target. When the bullets were striking the target, the big gun was triggered.

B-25 pilots had to maintain a straight and steady course in order to achieve a hit at 2,000 yards. The rate of fire depended on how rapidly the loader could open the breech, load the 10-pound shell, and close it.

Some pilots liked the heavy hitting 75, while others preferred having several machine guns instead. “I think we carried about 11 or 12 shells,” Coble remembered. “Garvin, my bombardier, loaded them. When it went off, the whole plane just bucked and we heard a big WHUMP!”

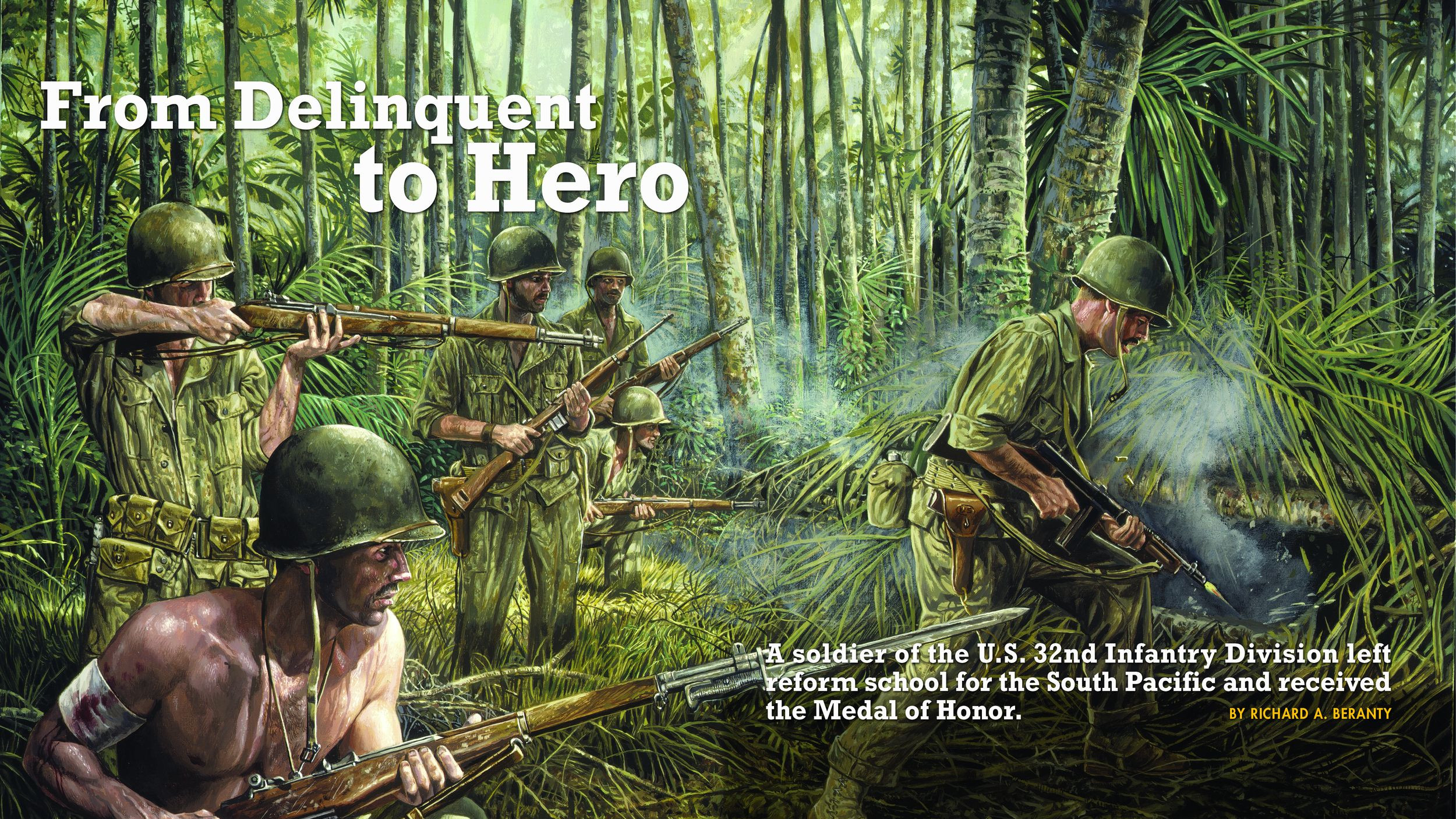

German forces in the Aegean Sea were scattered over scores of small and large islands. Hitting them in daily raids was the job for the 379th Squadron.

“The Krauts had a lot of fighter strips on those islands,” Coble continued. “On most missions we flew low under their radar. We’d be over their island bases to drop 23-pound parachute fragmentation bombs. They did a lot of damage, wrecking planes, but left the airfields intact. Then we’d fire a couple of shells at whatever looked good.”

Coble had one memorable experience with the cannon. “On 18 February we found a German patrol boat about five miles off the Turkish coast. It was about 50 feet long. I squeezed one off and the shell went in the stern of the boat. It blew apart like kindling. One crewman jumped clear. All these years later I can still see him.”

Coble at last had his chance to put into practice the art of skip bombing German ships.

“When we saw a Kraut ship, I flew about 50 feet altitude at 220 knots. That was plenty low,” Coble smiled. “At that speed the target came up very fast. I adjusted my course as they tried to evade. When we were about 500 yards out, I toggled off the bombs and pulled up to clear the ship’s masts. Those 500-pounders skipped a couple of times and slammed into the hull. The trick was to not be right over it when they exploded. Usually my tail gunner told us if we got a hit. We sank three German ships off Crete,” Coble said with pride.

By early 1944, the German ships were trying to dash across the sea at night to unload and return before daybreak to avoid the deadly Mitchells. Less than 50 percent returned to their home ports.

“On 22 February, 1944, we sank a small cargo ship and then these Kraut fighters got on our tail and chased our ass the whole way around the eastern end of Crete,” recalled Coble. Pisonya’s gunners were credited with shooting down a German Me-109 and Ju-88 over the Aegean.

When the Ninth Air Force was disbanded, the 310th Bomb Group transferred to Corsica, where they were given new B-25Js. The “J” model had the greenhouse nose. Bombardier Garvin finally had the chance to use a bombsight rather than load cannon shells.

The Twelfth Tactical Air Force, under General John Cannon, had close to 2,500 fighters, Douglas A-20 Havoc attack bombers, and medium bombers based on eight airfields. The rocky but idyllic island was perfectly suited for basing American tactical aircraft for operations in Italy, southern France, and Austria. It soon gained the affectionate nickname of “USS Corsica.”

“I liked Cannon,” affirmed Coble. “He was quiet, very friendly. Not your usual general. I flew him to the officer’s resort at Il Rousse, on the northwest corner of Corsica.”

On the eastern coast were the three air bases of the new 57th Bomb Wing, massing nearly 300 medium and light attack bombers.

“Our base was in Ghisonaccia, Corsica. That was a nice place compared to Libya. I loved that island. The people were so friendly. When we were grounded for bad weather, some of us went into town to a small restaurant. The food and wine were terrific.”

However, the 379th Squadron’s airmen at Ghisonaccia had the distinction of being treated to a breakfast to remember. “Our mess cooks had these young Corsican boys helping out,” said Coble. “Well, one morning this one kid made a mistake and put air slake lime in the batter instead of pancake flour. We all got so sick, vomiting, diarrhea, just terrible. Lasted for about three days.”

That little incident was related in Joseph Heller’s bestselling novel Catch-22 about a B-25 group on the fictional island of Pianosa. Heller was a veteran of 60 missions as a bombardier with the 488th Bomb Squadron, 340th Bomb Group.

Bad food notwithstanding, the 310th Bomb Group flew bombing missions at high and low altitudes against land targets in Italy. “Ghisonaccia was so close to Italy that if we flew straight east, we’d be there in 15 minutes. Why the Germans never came out and bombed us, I’ll never know,” Coble said.

Operation Shingle, the Anzio landings in January 1944, had bogged down on the beachhead for three months while relentless German counter attacks hammered the American and British positions.

In the spring of 1944, Coble’s crew, along with the rest of the 57th Wing, joined in Operation Strangle, a systematic effort to destroy all German communication links and supply lines during the Italian campaign. Fighter bombers and medium bombers attacked German tactical assets, such as shipping, railroads, marshaling yards, truck yards, fuel storage tanks, supply dumps, tunnels, and bridges. Bombardiers and gunners were told to hit switches, repair yards, locomotives, and other targets that could not be easily repaired or replaced.

“We hit railroad bridges and tunnels from Rome north. That also included a raid on Monte Cassino on 15 March,” Coble said, referring to the 6th century monastery which was suspected of being used as a German observation post for the Gustav Line. The destruction of the ancient abbey was considered one of the worst cultural losses of the war.

Coble commented, “We had plenty of Mustangs for fighter cover, so the Luftwaffe wasn’t much of a problem.”

Coble’s own crew and some of the 379th gained a reputation for bombing bridges. “You can approach a bridge by flying along the road or down the valley. But we just flew right down at them from a high angle. We were called ‘The Bridge Busters,’” he smiled.

Strangle was succeeded by Diadem, aimed at breaking a hole in the German lines to allow the 70,000 Allied troops to break free of the Anzio beaches and march inland.

Diadem began on May 15 and wreaked such havoc with the Germans they were only able to transport about 500 tons of supplies for the 14 divisions engaged. Without railroads, the German Army was forced to use trucks at night. But this too proved costly, as A-20 attack bombers carrying parachute flares illuminated the supply lines and destroyed the trucks in place.

On May 25, 1944, the German 10th and 14th Armies began the withdrawal from the Anzio region, pursued by Twelfth Tactical Air Force fighter bombers. About 100,000 American troops, preceded by heavy artillery fire, broke free of the beachhead and marched toward Rome.

Coble and his crew were in the air that day. “We flew in from the coast. The sky over the beach and roads were just full of smoke and tracers, explosions and fire. The troops were a mass of men moving inland. It was a sight to behold.”

One mission stands out for Coble. “On 10 June, I led six ships on a mission to hit a railroad bridge at Calaforia, Italy. The 88mm flak was terrible. It shot down the third element leader, Ernie Kulik. His plane took a direct hit. We saw four chutes come out, but three were on fire. My co-pilot was hit in the head. The main gas line in the right carburetor was badly hit but that amazing engine kept running. We landed with 145 holes in the plane.”

That mission earned Lieutenant Truman Coble the Distinguished Flying Cross. The citation reads: “For extraordinary achievement while participating in aerial flight as a pilot of a B-25. On 10 June 1944, Lt. Coble led a six-plane flight in an attack upon a railroad bridge at Calaforia, Italy. Despite intense anti-aircraft fire which heavily damaged his airplane upon the approach to the target, Lt. Coble, displaying great courage and superior flying ability, maintained his crippled plane on course, thereby enabling his bombers to release their bombs with devastating effect upon this vital link in enemy communication lines. On more than fifty-five combat missions his outstanding proficiency and steadfast devotion to duty have reflected great credit upon himself and the Armed Forces of the United States.”

Bud Coble finished his tour with the 310th and was sent home in late June 1944, after flying 56 combat missions. The 310th Bomb Group, as part of the 57th Wing, participated in more campaigns, including the build-up to Operation Dragoon, the invasion of southern France in August 1944.

The group earned two Distinguished Unit Citations for action in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations. They reached the number of 500 missions sooner than any other group in the European Theater. In 989 missions they were credited with shooting down 121 enemy aircraft, including a captured Curtiss P-40. Skip bombing and cannon attacks on German shipping resulted in the sinking of 206 vessels. Among these were a German cruiser and two destroyers. Over 23,900 tons of bombs were dropped while the B-25Gs fired 1,998 75mm cannon shells.

Bud Coble took a job at Sears, where he worked for 43 years. “I had met Winifred, my future wife, in Cairo while I was recuperating from an illness,” he explained. “She was an Army nurse, a 2nd Lieutenant. We were married two years later. I technically outrank her, but she’s my wife so her orders stand.”

Coble is typical of the decidedly atypical airmen who flew B-25s in the Mediterranean Theater. At dangerously low altitude and face-to-face with German flak, they slowly and effectively ground down the Axis ability to fight. From North Africa to Sicily, Palermo, Rome, Naples, Anzio, the Po Valley, and into southern France, the Mitchells were there.

Mark Carlson has written on numerous topics related to World War II and the history of aviation. He resides in San Diego, California.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments