By Kelly Bell

On the night of September 14, 1942, the men aboard the U.S. Navy submarine Wahoo spotted smoke rising from the funnel of a vessel emerging from Truk’s north pass. Lieutenant Commander Marvin Kennedy uncorked four torpedoes at the 6,438-ton Japanese freighter Kamogawa Maru. The first three missed, but the panicked Japanese helmsman swerved directly into the path of number four.

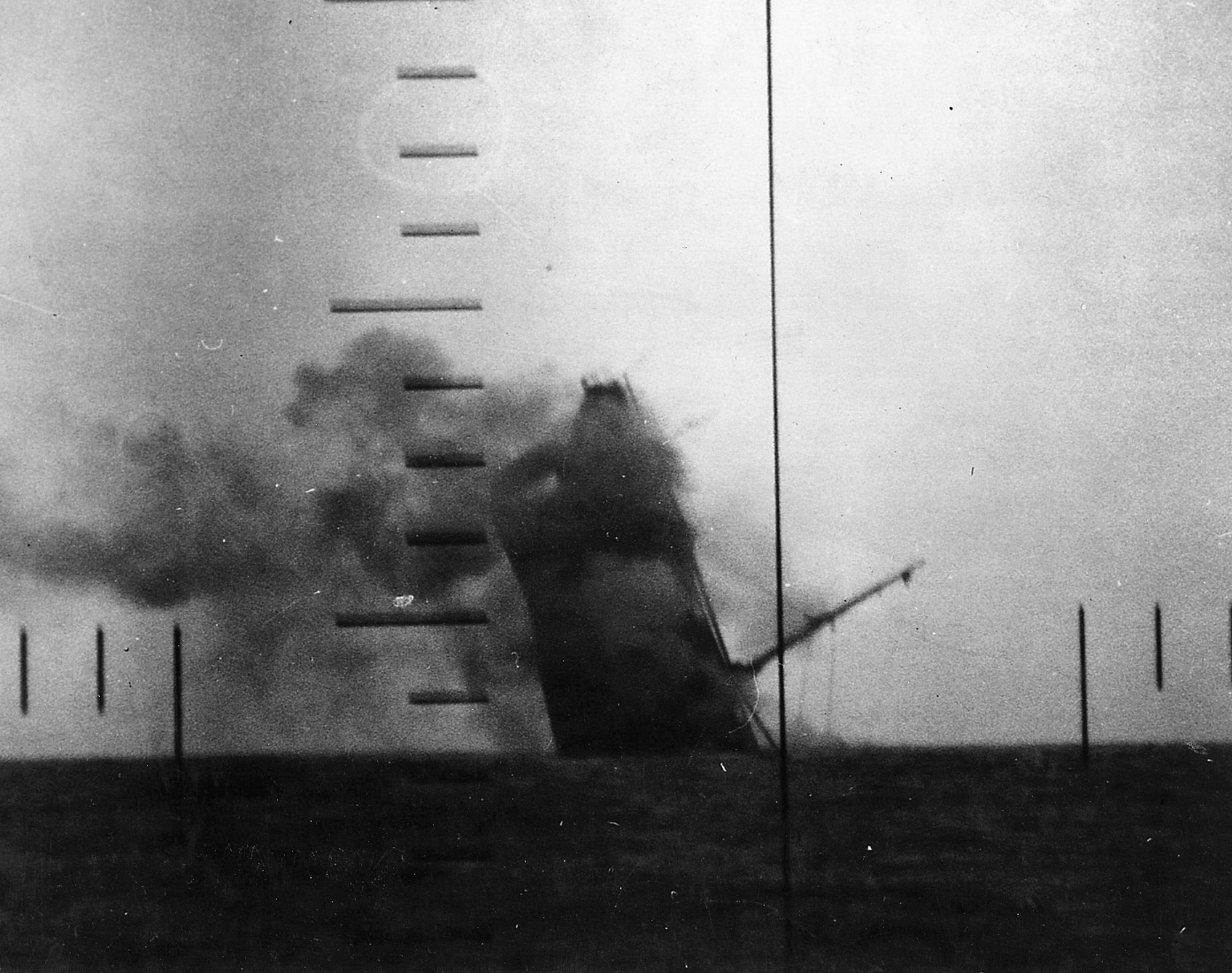

The missile hit squarely amidships on the port side and set off a hold full of ammunition. As the doomed ship went up like a volcano an escorting destroyer commenced dropping depth charges. Kennedy took his boat down to a depth of 230 feet, below a temperature gradient that reflected sonar waves, hiding the hunters from the enraged escorts.

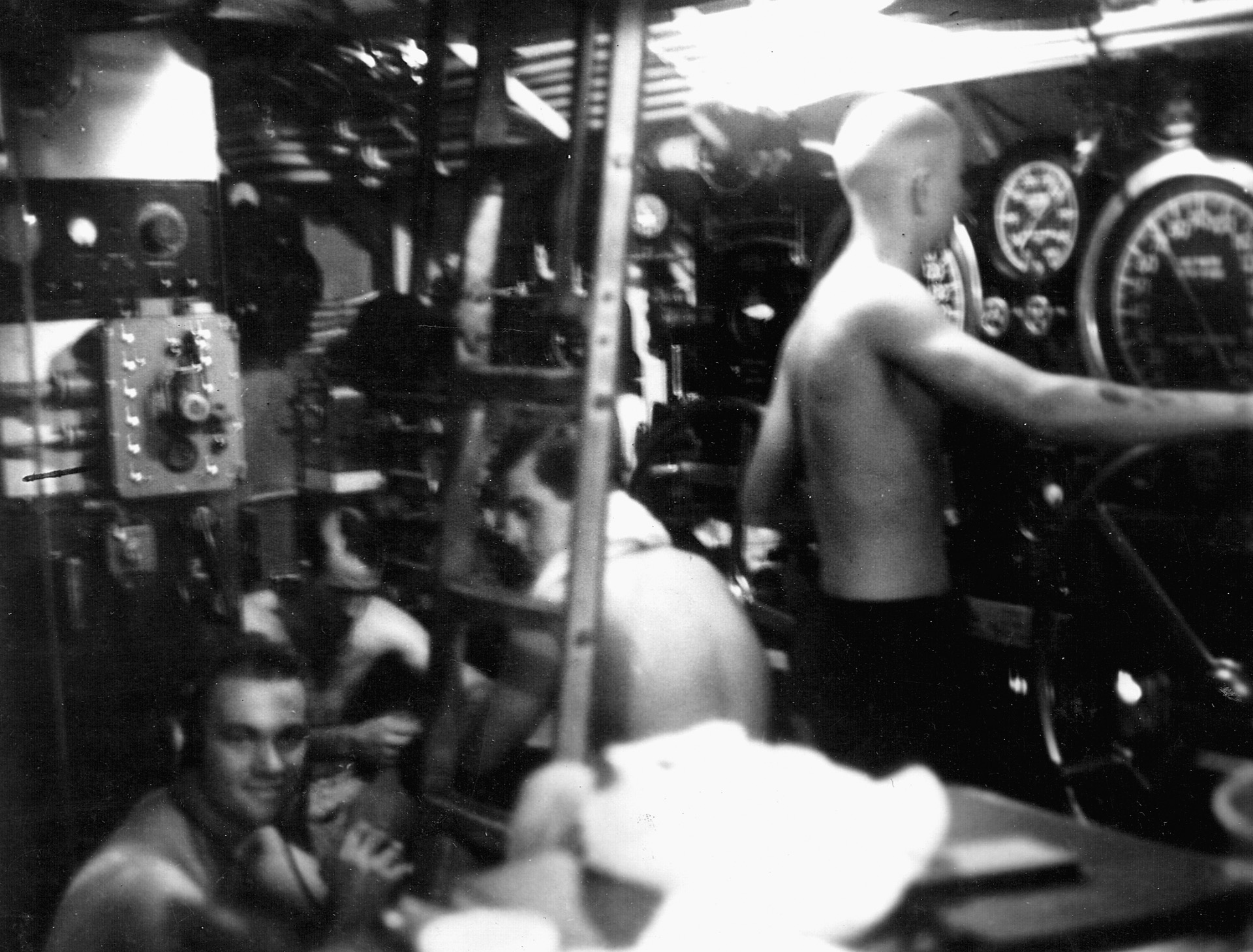

The U.S. Navy had launched Wahoo from its Mare Island construction site off San Francisco on St. Valentine’s Day in 1942. Wahoo had already been under construction when the armed forces of Imperial Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. The unfinished machine’s mission was handed down from the Navy high command even before her launching: “Conduct unrestricted submarine warfare.” Her crew could hardly wait to lash out at the faraway island nation that had ruthlessly wounded their country. They had no way of knowing how much vengeance they would exact. By summer, Wahoo was completed, her men trained on how to use the vessel in battle, and her stores full. She churned eagerly into the Pacific at 10:00 on the morning of August 23, 1942.

For American forces to maintain the offensive in the Pacific, the bristling Japanese bastion at Truk Atoll had to be neutralized, or at least pressured, to prevent the reinforcement of garrisons occupying islands that were marked for assault. In the midst of the Caroline chain, Truk is encircled by coral reefs that make it impossible for heavy warships to get within shelling range of shore targets. With Imperial air and sea forces menacing any task force that might try to bypass the facility, the installation was a hornets’ nest awaiting victims. With no bomber bases in range of Truk at the time, submarines were the only weapons the Allies had to wield against this hot spot. Wahoo arrived on the morning of September 4.

Shortly after dawn on the 6th, Kennedy’s lookouts summoned him to the periscope. He fired three torpedoes at six-second intervals, but all missed the freighter steaming southeast across his bow. For over a week, the ocean was then barren of targets as the impatient Americans searched for prey. On the evening of September 14, a torpedo in the number one forward bow tube spontaneously activated itself and crashed through the chamber’s outer door.

Although the warhead did not explode, the missile remained protruding halfway out of the silo. This made the boat seriously susceptible to depth charges, but the crewmen had no thoughts of aborting their cruise. Instead, they ignored the faulty torpedo jutting from their bow and sank Kamogawa Maru.

Following this inaugural kill, the seas again became sterile, and after a full month of fruitless hunting a disillusioned Kennedy returned to Pearl with the defective missile still poking from its tube. For three weeks Wahoo was repaired and restocked while her men chafed to return to predatory pursuits.

On November 8, a grim Kennedy again headed west with a rested crew equally anxious to prove itself. The assigned patrol area was north of enemy-held Bougainville Island. Japanese supply and troop convoys bound for embattled Guadalcanal traversed this sector regularly. With the Imperial Navy in control of the seas surrounding the Solomon Islands, it was critical to block the shipping lanes if the American Marines who had landed on Guadalcanal in August were to have any hope of victory.

Hunting was poor until December 10. That evening Wahoo attacked a convoy between Buka Island and the Kilinailau Islands. The resolute Americans closed to just 700 yards from 8,748-ton Syoei Maru before blowing her into a towering bonfire. Diving away from depth-charging escorts, the submarine was shaken by the blasts, but managed to escape.

The Japanese apparently realized an especially dangerous raider was on the prowl and decided to fight her with her own kind. On the morning of December 14, a Japanese I-Class submarine blithely churned across Wahoo’s bow. Stumbling from the shower, Kennedy rushed dripping and stark naked to the periscope and directed his forward torpedomen as they fired three times from just 800 yards. One torpedo banged into the enemy’s hull just ahead of her conning tower, sending her under in a twinkling.

Five days later, Kennedy and his crew reached the end of their patrol and headed for Australia. Kennedy was reassigned, and his first officer, Lt. Cmdr. Dudley Morton, took command for war cruise number three. On January 15, 1943, Wahoo set out for the coast of New Guinea.

On the afternoon of the 24th, Morton was lining up on a small Japanese naval anchorage on New Guinea’s eastern shoreline when new First Officer Richard O’Kane, who was at the second periscope, shouted, “Destroyer underway! Angle ten port!” With insufficient time or depth to escape, Morton turned his boat nose to nose with her attacker and began pumping out torpedoes. The first four missed, but the fifth ripped the destroyer wide open. With their victim going down headfirst, the Americans fled to the open sea before enemy planes could arrive.

Wahoo sniffed out a Japanese troop convoy of three freighters on the morning of January 26. Using both torpedoes and deck guns she sank two of the enemy vessels and seriously damaged the third before it managed to escape. By 3 pm, however, the submarine had caught up with the wounded transport, now accompanied by a tanker. Morton quickly sank the 6,515-ton oiler Manzyu Maru, but as he turned to attack the damaged freighter a destroyer came boiling in from the submarine’s port side.

Diving deep, the skipper correctly anticipated the transport’s course and steered toward her and away from the warship. The raider surfaced as her victim was passing 3,000 yards to the stern. Taking careful aim, Morton directed the aft torpedo room crewmen as they primed their last two missiles. It took a full three minutes, but both charges squarely hit the 9,684-ton Arizona Maru, sending her cargo of infantry reinforcements to the bottom.

During a 14-hour rampage, Wahoo had sunk four vessels totaling 30,557 tons. Counting the destroyer she had bagged earlier, she had five kills before even reaching her patrol area. Out of torpedoes, Morton turned for Pearl. That evening, the jubilant crew received a wireless message directly from Admiral William Halsey, congratulating them on their success. They docked on February 7.

The legendary patrol took just 24 days—the briefest completed wartime voyage ever made by an American sub. After only eight days at Pearl Harbor, the Wahoo steamed past the charred hulk of the battleship Arizona and steered westward. After refueling at Midway on the 27th, the submariners churned for the East China and Yellow Seas. On March 10, they arrived off the Japanese Home Island of Kyushu. The next morning they were in the shipping lanes leading from the island’s southwestern ports to the Empire’s occupied territories.

These waters proved barren, so on the 13th Morton turned his prow toward what he hoped would be a more crowded seascape off Korea. Just before daybreak on March 19, a silhouette appeared on the horizon. A colorful dawn was blushing behind a large transport. Every man on board was keen to try out their new armament. Back in Pearl, Wahoo had been stocked with torpedoes capped with a new explosive called torpex. Hoping this invention would cut down on the number of shots required to sink each target, the skipper yelled, “Fire just one torpedo!” The interior of the sub was so silent with anticipation that every man on board heard First Officer Richard O’Kane slap the firing plunger.

Forty-nine seconds later, the submariners were startled by a deafening report they had never dreamed could come from one torpedo. At the attack periscope, Chief Thomas McGill watched stunned as the freighter’s aft section disintegrated. Less than three minutes later nothing remained on the surface except small bits of flotsam. The victim had been the 4,065-ton Nanka Maru, and even if her wireless had survived the blast there had not been time to broadcast warning of the fearsomely armed predator. Sure enough, just before 8 am, the raiders sank the 5,725-ton transport Tottori Maru in the same area. As a storm began to whip up the ocean, Wahoo turned toward the Korean port of Chinnampo.

March 22 was a busy day. At dawn the Americans blew a never-identified freighter from the water. At 9:30 they closed to just 800 yards from the transport Nita Maru and drilled her with two torpedoes aft.

That evening, the hunters set course for the heavily traveled area around the Laotiehshan Promontory, which juts into the Gulf of Pohai. In the early morning hours of the 23rd, they sank the 2,427-ton coal carrier Katyosan Maru, but at 10 am they heard the boom of depth charges back at the site of the sinking. Realizing destroyers were on their trail, they slipped out of the sector.

At sunset on March 24, Morton’s lookouts spied a large tanker steaming on a course for Port Arthur. Lining up his after tubes, the skipper fired from a perfect right angle at 1,700 yards. The first two torpedoes malfunctioned and exploded just 18 seconds into their runs. The third missile shot into the huge, momentary crater its predecessors had blasted in the water and went tumbling out of control. The alerted enemy dodged a fourth round and opened up on Wahoo with deck guns using flashless powder.

Diving to safety, the submariners quickly resurfaced and set out for their target’s presumed destination of Dairen Harbor. Looping in front of their quarry, they intercepted her just four miles outside the safe anchorage and in a position where she was silhouetted by the rising moon. At 9:22 pm, Morton pointed his forward tubes at the target 1,200 yards ahead and fired three torpedoes. The first two missed, but the third was a direct hit that ignited over three million gallons of oil and gasoline. The conflagration engulfed the 7,499-ton Syoyo Maru and lit Dairen Harbor midday bright. Although still not out of ammunition, Wahoo already had seven kills on this patrol.

At 3:00 the next morning the Americans had to pump a torpedo and countless rounds from their deck guns into a small merchantman that was very loath to sink. As the little boat finally bubbled under, an armed tanker charged Wahoo.

The Japanese opened up on the sub with 40mm antiaircraft guns as soon as they spotted her. Retreating on the surface, Morton answered with his four-inch deck cannon. His fifth round silenced the tanker’s guns and crippled her engines. Swapping ends and moving in for the kill, the raiders shelled their foolish attackers into a roaring furnace. By 6:15 am both of these latest victims had gone down.

The first of the morning’s kills had been a Sinsei-class freighter, and the second was the 1,000-ton Hadachi Maru. In the growing daylight the Americans saw the mast of an approaching destroyer and began to notice the drone of warplanes. With just two torpedoes remaining, the raiders submerged and steamed quietly out of the area.

Early on the morning of March 29, Wahoo was prowling north of Formosa when her radarman detected a large vessel southbound out of Shanghai. Seconds after Morton fired his last two rounds from just 900 yards, things got very hectic aboard the sub.

Many of the submariners were unaware of the attack on the suddenly appearing ship, and both torpedoes were direct, almost simultaneous strikes. The deafening explosion reverberating through Wahoo panicked many of her crewmen, who mistook the blast for depth charges. As his terror-stricken men lunged for life preservers O’Kane had a sailor shout over the loudspeaker, “The sound you hear is the ship breaking up!” The man forgot to say it was an enemy ship that was sinking, and the bedlam increased. In the chaos O’Kane and Morton forgot to order the helmsman to turn aside, and the sub almost collided with the sinking 5,193-ton freighter Kimisima Maru. After shrieking “Full right rudder!” at the pilot, the executive officer hastily toured the boat and assured the crew all was well.

Counting a small radar trawler they had shot up with deck guns on March 27, the raiders had destroyed 10 Japanese vessels on this cruise. On April 6, they arrived back at Midway to another warm reception. Extensive repairs to Wahoo’s electrical system kept her in port until the 25th. By then, Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz had awarded Morton a Navy Cross and O’Kane a Silver Star. Both officers dedicated their decorations to their crew and ship.

When Wahoo returned to her sprawling hunting ground, sister subs Steelhead, Pickerel, and Scorpion accompanied her. They conducted a futile search for a Japanese flotilla which counterintelligence sources had reported headed for the Aleutians. When the sharks found no trace of the fleet, they separated and headed for individual patrol sectors. Morton and his crew arrived in the freezing seas off the Kurile Island of Onnekotan on May 2.

On the 4th, the hunters wounded a warplane transport that managed to reverse direction and escape back into Etorofu Strait. On May 7, the Americans sank a 5,700-ton Yuki Maru-class cargo ship. The next day they attacked a freighter off Honshu’s northeast coast, but the first torpedo exploded prematurely, knocking the second one off course. When the third shot hit the target but failed to explode, a destroyer got a fix on the predator and attacked her with depth charges. Rattled by the concussions, the submariners managed to escape and set course for Kone Saki. At 2:30 the next morning they sank the 9,527-ton tanker Huzisan Maru and the 9,467-ton freighter Hawaii Maru. After more weapons malfunctions, Morton ran out of ammunition on the 12th and turned for Pearl.

Docking on May 21, Morton received a Gold Star to his Navy Cross, and O’Kane was awarded a second Silver Star. It was O’Kane’s last cruise aboard Wahoo. He was given command of the brand-new attack submarine Tang. It was literally a lifesaving promotion.

The acclaimed Wahoo sailed all the way to San Francisco for servicing and resupply. She was also a major draw for politicians, journalists, and sundry and assorted patriots. Her seventh patrol was scheduled to be a grand lark completely around the Japanese home islands and a cruise through the Sea of Japan. She embarked July 21, but after an unprecedented plague of weapons failures a disgusted Morton broke off the cruise early without having sunk any of the six ships he attacked. On August 29, 1943, America’s most lethal lady docked at Pearl Harbor for the last time.

On September 12, Wahoo left for the shipping lanes between Japan and the Asian mainland. Postwar examination of the Report of the Imperial Japanese Navy reveals that on October 2, 1943, the sub sank a 2,968-ton Taiko Maru-class merchantman. On the fifth she bagged a 9,000-ton troop transport, and the next morning picked off 1,288-ton Kanko Maru.

On the storm-lashed morning of October 9, she fired three torpedoes at another Kanko Maru-class ship. The first two missiles mortally wounded the target, but the third fish went haywire in the heavy seas. It circled back and blasted a gaping wound in Wahoo’s forward torpedo room. Two days later, Japanese artillerymen spied the crippled submarine churning along the surface of Cape Soya Strait and radioed the alarm.

Antisubmarine floatplanes and sub chasers quickly converged on and assaulted the hapless boat with a cascade of depth charges. By 1:30 pm the surface was coated with oil, wreckage, and dead fish. USS Wahoo was never heard from again.

Lieutenant Commander Dudley Morton received his second Navy Cross posthumously. Like 3,505 of his brother American submarine crewmen of World War II, he remains on eternal patrol. These men comprised just 2 percent of the Navy’s total wartime complement, but they accounted for over half of the Japanese shipping destroyed by Allied forces. With no heavy bomber airfields in range of Japanese industrial targets until the autumn of 1944, it was America’s submarines that choked off the Empire’s attempts to maintain its far-flung forces.

Before this war, Japan had no concept of naval defeat. The U.S. Navy’s submarines showed this ruthless enemy a lethal new type of warfare. Wahoo led the way and taught her sisters well.

Kelly Bell is a longtime freelance writer based in Tyler, Texas.

It’s pretty sad, and difficult to understand, how and why a country that produced atomic weapons could not make a torpedo that worked reliably until late in the war; by then, it wasn’t needed. Aircraft took over as the main offensive weapon and submarines were relegated to the unglamorous, but very important, life-saving duty of recovering downed fliers (one which became the President of the United States).

Amazing! Thanks!