By Pat McTaggart

During the winter of 1941, both the Red Army and the German Wehrmacht experienced a terrifying bloodletting. Adolf Hitler’s seemingly invincible armies, having advanced hundreds of miles inside the Soviet Union, were slowed by the October muddy season that had turned all but a few roads into almost impassible quagmires. Then came the snow and the cold—a paralyzing cold that was claimed as the worst in a hundred years.

On the night of December 5, STAVKA (the Soviet Supreme Command) launched a massive offensive that drove the Germans back from the gates of Moscow. By the end of March 1942, the Soviet offensive had run its course. Red Army forces had advanced almost 200 miles in some areas, at the cost of more than a half-million casualties. The Germans also suffered heavily. According to an entry in Army Chief of Staff GeneralOberst Franz Halder’s diary, the total of Germans killed, wounded, and sick between November 1, 1941, and April 1, 1942, was almost 900,000, with the majority being lost on the Eastern Front.

Although the main Soviet effort took place on the northern and central sectors of the front, Russian forces had also made gains in the south, especially in the area around the eastern Ukrainian city of Kharkov. In January 1942, four Soviet armies struck the boundary of the German 6th and 17th Armies in the area near Izyum, about 70 miles southeast of Kharkov. The Russian attack was aimed at creating a future jumping-off point from which they could strike at the main southern crossings of the Dnieper River. They would also be in a position to attack either north toward the key communication center of Kharkov or south into the rear of the 17th Army.

The German Army, trained as an offensive force from the beginning of its revival in 1933, was forced to improvise its defensive operations. The 6th (GeneralOberst Friedrich Paulus) and 17th (General der Infanterie Hans von Salmuth) Armies were no exception. As the Russians struck the German front line, it was often up to the commander at the scene to make life or death decisions for his men. While tank-supported infantry units overran several German positions, others held out, creating breakwaters in the ocean of attacking Russians.

Some German commanders pulled their forces back in an orderly retreat until they found suitable terrain in which to make a stand. The small villages dotting the countryside gave concealment as well as protection from the harsh winter weather. Once such a village had been reached, the Germans wasted little time in creating an improvised defense, using wrecked vehicles, rock walls, and everything available to strengthen their position.

By the end of the second week of the offensive, these “hedgehog” defenses were beginning to take their toll on the advancing Soviets. If the first echelon of attacking Red Army troops bypassed a German strongpoint, the Germans would launch limited attacks on their rear, or at the second or third waves following the breakthrough forces. On the other hand, if breakthrough forces wanted to overcome the strongpoint, they would have to stop, deploy, and then fight a costly battle, which depleted men and equipment. Either way, the German “hedgehogs” remained a thorn in the side of the Red Army’s offensive.

Eventually, German reinforcements arrived and finally stopped the offensive. Once the spring mud brought all operations to a halt, both sides had time to re-position units and build up their depleted ranks. The Russians had stabilized their line after advancing almost 60 miles, creating a bulge south of Kharkov measuring about 60 by 45 miles.

Thanks to His Friendship with Joseph Stalin Timoshenko was Spared From the Bloody Red Army Purge

The Izyum Bulge, as it was called, presented several options and challenges for both sides. For the Russians, the bulge could be used as a staging area and jumping-off point to retake Kharkov or to threaten the lines of communication of Germany’s southern armies by striking at the key Dnieper River crossing points at Dnepropetrovsk and Zaporozhye. On the German side, the bulge represented a chance to destroy a large number of Soviet forces in a textbook pincer attack that would eliminate the Russian threat and straighten the front line.

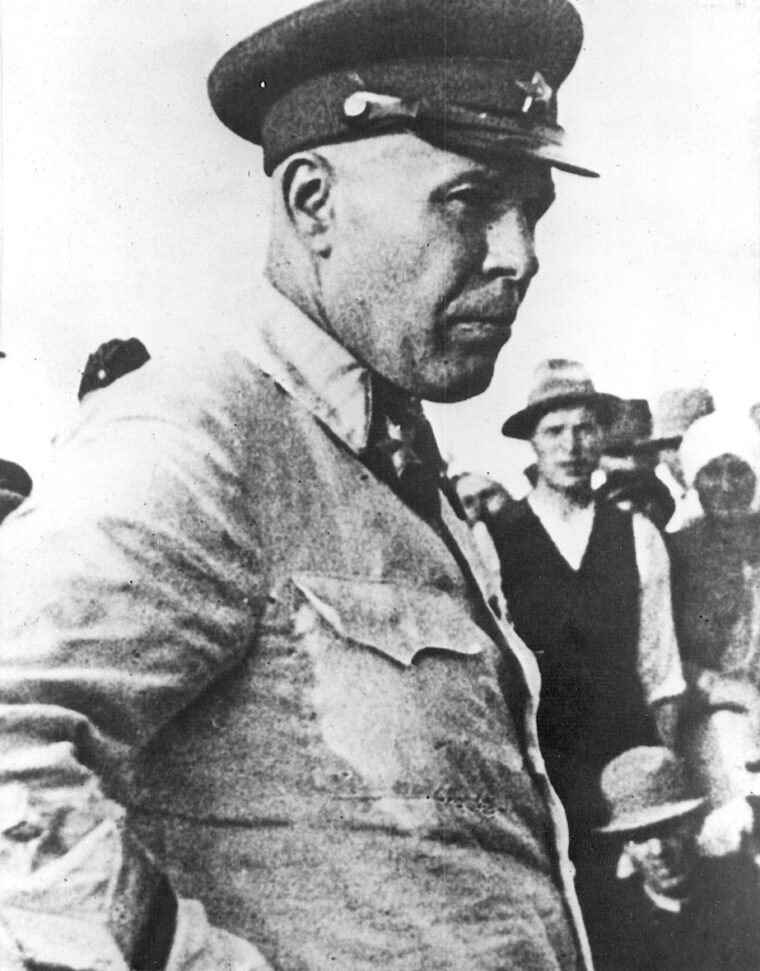

Throughout the early spring of 1942, both the Soviet and German high commands worked on plans to utilize the bulge to their best advantage. Marshal Semyon K. Timoshenko, commander of the Southwest Theater as well as the Southwest Front, political commissar Nikita S. Khrushchev, and Timoshenko’s chief of staff, Marshal Ivan Bagramyan, went to Moscow in late March to present a proposal aimed at clearing the Germans east of the Dnieper from Gomel to Cherkassy.

Timoshenko was born in 1895. During the Russian Civil War, he served as a cavalry officer in the Red Army, where he met and became friends with Josef Stalin. As he rose through the ranks, Timoshenko was sheltered from the bloody purges that decimated the Red Army in the 1930s by his friendship with the Soviet leader.

After his victory against Finland in 1940, Timoshenko was promoted to Marshal of the Soviet Union and was appointed Defense Minister. In that position, he labored to counter the disastrous consequences of the purges by improving training and reorganizing the crippled army.

When Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union, began, he was appointed commander in chief of the Red Army, a post that lasted about a month until Stalin took the position for himself. Commanding the Western Theater, Timoshenko’s divisions were entrusted with slowing the German advance on Moscow. He replaced Marshal Semyon Budenny as commander of the Southwest Theater in September 1941.

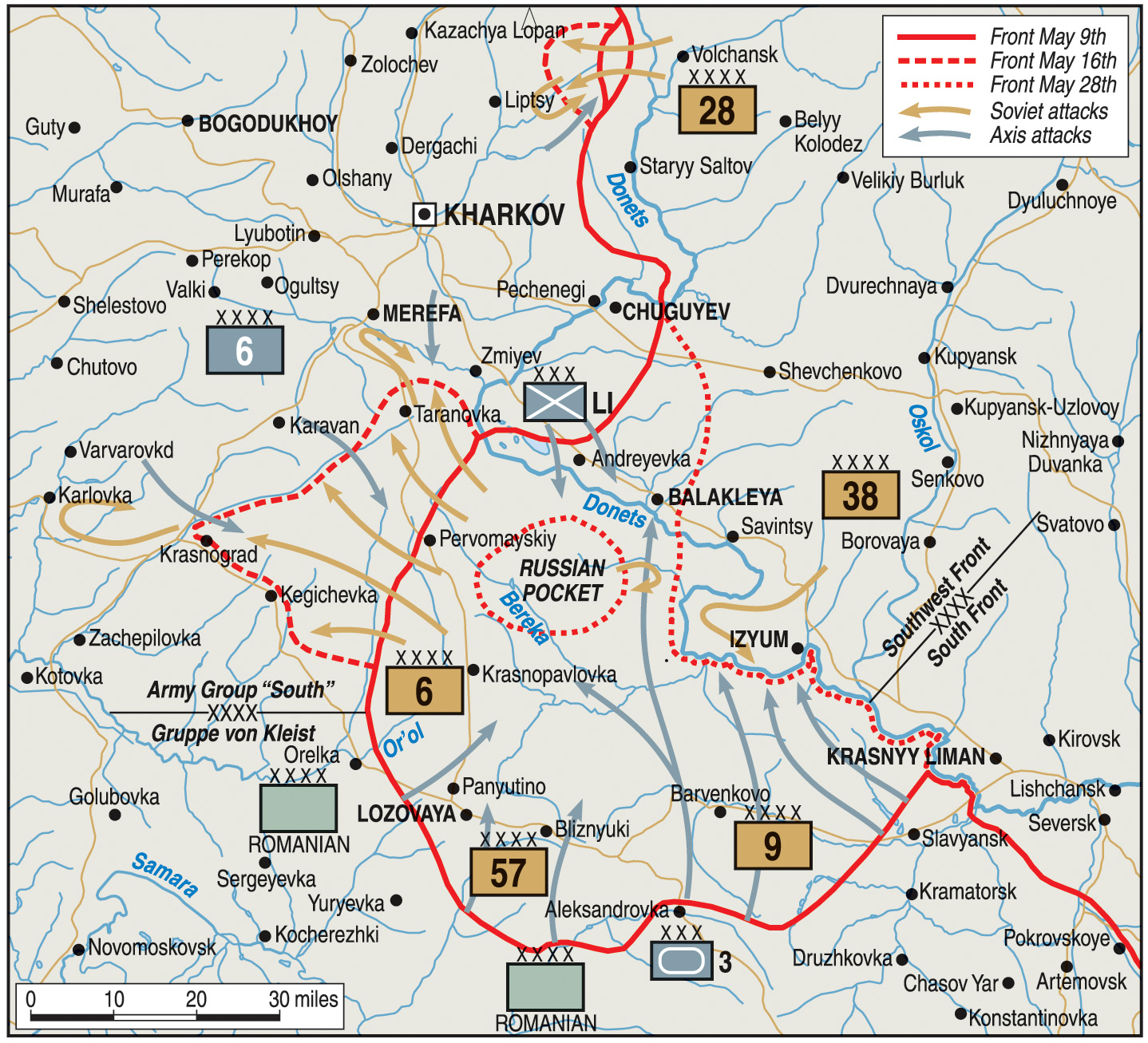

After Timoshenko and the others met with Stalin and the STAVKA, a modified version of an initial plan, aimed at the liberation of Kharkov with a later thrust to Dnepropetrovsk, was approved. The attack would be augmented by an assault from the Volchansk salient, about 20 miles northeast of Kharkov. It was hoped that the two-pronged attack would encircle and destroy most of the German 6th Army. The attack was scheduled to begin on May 12.

Generalfeldmarschall Fedor von Bock, commander of Germany’s Heeresgruppe Süd (Army Group South), was also planning a mid-spring offensive. His army group had been given the mission of clearing the Soviets from the Caucasus, taking the vital oil fields located there, and capturing the industrial city of Stalingrad, located more than 300 miles to the east of Izyum. To accomplish this daunting task, it was imperative that the Izyum Bulge be destroyed.

Due to the meandering Donets River, von Bock’s plan, codenamed Fridericus, envisioned a two-pronged attack that would cut the base of the Soviet bulge by attacking along the west bank of the river. Paulus’s 6th Army would strike from the north, while General der Kavallerie Eberhard von Mackensen’s III Panzer Corps, part of Army Group von Kleist, would attack from the south.

When presented with the plan, Hitler and Halder wanted the attack to take place on the eastern bank of the Donets. While von Bock and Berlin worked out the details, both the Russians and the Germans beefed up their offensive forces with reinforcements. Because of delays caused by lack of transportation, the German operation, now codenamed Fridericus II, was set to begin on May 18.

Timoshenko had amassed a formidable amount of men and equipment for his offensive. His command, which included the Southwestern and South Fronts, consisted of approximately 640,000 men, 1,200 tanks, 13,000 mortars and guns, and 926 aircraft. With these forces, he outnumbered the Germans facing him by a ratio of 3-to-2 in men and 2-to-1 in tanks. At the breakthrough points, that ratio would be much greater.

Facing the Southwest Front was Paulus’s 6th Army. Paulus had taken command of the Army on January 1, 1942, when the Soviet Winter Offensive was in full swing. Born in 1890, Paulus had served in staff positions since the beginning of the war. Before becoming assistant chief of staff for operations in the general staff of the Army in May 1940, he was chief of staff of the 10th Army and the 6th Army, respectively.

Arriving at his headquarters in January, Paulus was faced with a fragmented command and a Russian attack that had torn a large gap in his line. Having never commanded so much as a division, the new Army commander seemed at a loss as to what to do. Luckily, his staff and his field commanders were already at work, eventually stopping the Soviet drive.

With impending May attacks on both sides, it might do well to look at the differences in command control as both forces prepared for their offensives. At this stage of the war, the Soviet system allowed for little or no deviation from the operational plan. Commanders were hamstrung by orders that came from Moscow. Those commanders who failed to follow the plan often found themselves relieved and standing before a tribunal that had the power to sentence the offender to death or service in a penal battalion—another form of death sentence. If a situation arose that made a change of plan imperative, the “suggestion” would have to be forwarded to Moscow for approval. Soviet commanders were also hampered by political commissars who had a say in military operations as they progressed.

German and Russian Armies Planned to Attack Each Other in the Same Place at Nearly the Same Time

On the German side, initiative was encouraged. General directives would be issued and, while his forces were still successful, Hitler would more often than not let the commander in the field implement the “nuts and bolts” of an operation. Hitler’s winter “stand fast” order and the meddling in the Izyum operation were not the norm at this point of the war. After the Stalingrad fiasco, however, his interference, even at the lower levels of command, led to disastrous results.

With two armies preparing to attack each other in the same spot at almost the same time, it is obvious that the plans of both sides would not survive the first stages of combat. Time would be of the utmost importance, and it would be up to the field commanders to make their own decisions on how the course of the battle would flow, regardless of the consequences.

According to the modified plan hammered out by Timoshenko and STAVKA, Lt. Gen. A.M. Gorodnyanskii’s 6th Army (eight rifle divisions, four tank brigades, and 14 artillery regiments) and Maj. Gen. L.V. Bobkin’s Mobile Operational Group (two rifle divisions, three cavalry divisions, and one tank brigade) would break through the German lines on a 15-mile front. Gorodnyanskii also had five tank brigades and two motorized rifle brigades slated as exploitation forces when Timoshenko felt the time was right.

On Gorodnyanskii’s left flank, Lt. Gen. K.P. Podlas’s 57th Army and Lt. Gen. F.M. Kharitonov’s 9th Army were also poised for limited advances. These forces would be used to protect the southern flank and fend off any German counterattacks coming from that area. Between them the 57th and 9th Armies had 25 rifle and cavalry divisions, 11 tank brigades, and a motorized brigade.

In the Volchansk salient, Lt. Gen. D.I. Ryabyshev’s 28th Army was to head due west, preventing reinforcements from the German 8th Army from helping Paulus. Ryabyshev had a total of 13 rifle and cavalry divisions, two tank brigades, and a motorized rifle brigade at his disposal and would also be supported on his flanks by units of the 38th and 21st Armies.

As a reserve force, the Southwest Front had a cavalry corps and a 100-strong tank brigade. If necessary, Timoshenko could also call on the neighboring South Front’s reserve, which consisted of seven rifle divisions and a tank corps, for additional forces. The brunt of the Soviet attack would fall on the German VIII Army Corps, commanded by General der Artillerie Walter Heitz.

Heitz had one German infantry division (the 64th under Generalleutnant Rudolf Friedrich), the 108th Hungarian Light Division, and the 454th Sicherungs Division under Generalleutnant Arthur Schubert. The 454th was a security division originally tasked with guarding key installations and fighting partisans in the rear areas. Because of the losses suffered by the 6th Army during the Soviet Winter Offensive, the division was now serving as a front line unit, a task for which it was thoroughly unfit.

The 6th Army had three other corps holding the Izyum Bulge. General der Infanterie Karl Adolf Hollidt’s XVII Army Corps had two infantry divisions, the 79th (Oberst Richard von Schwerin) and the 294th (Oberst Johannes Block). Generalleutnant Walter von Seydlitz-Kurzbach commanded the LI Army Corps composed of the 44th (Generalmajor Heinrich Deboi), 71st (Generalmajor Alexander von Hartmann), and 297th (Generalleutnant Max Pfeffer) Infantry Divisions.

The XXIX Army Corps (General der Infanterie Hans von Obstfelder) consisted of three infantry divisions: the 57th (Generalleutnant Oskar Blümm), the 75th (Generalleutnant Ernst Hammer), and the 168th (Generalmajor Dietrich Kraiss). As a reserve force, Paulus had Generalleutnant Hans-Heinrich Sixt von Arnim’s 113th Infantry Division as well as the 23rd Panzer Division (Oberst Heinz-Joachim Werner-Ehrenfeucht), which was refitting near Poltava after being transferred from France in March. Elements of Generalmajor Hermann Breith’s 3rd Panzer Division were also arriving in the 6th Army sector, being transported by rail from Kursk to take part in the upcoming Fridericus operation.

With both sides amassing men and materiel for offensive operations, German and Soviet intelligence services proved to be woefully inadequate. In fact, neither side seemed to be aware of an impending attack from the other. Because of the German transportation problems, it was Timoshenko who was able to strike first and achieve surprise.

On May 12, Gorodnyanskii and Group Bobkin hit Heitz’s VIII Army Corps with a vengeance. As Russian artillery shells slammed into enemy positions, the Red Army advanced. The German and Hungarian soldiers crouching in their foxholes heard the blood-curdling battle cry “Urra!” as the Soviets surged forward. Most of them had little time to man their weapons before the Russians were upon them.

Those stunned Axis forces lucky enough to survive the initial assault were soon streaming back to secondary positions with Russian tanks and infantry hot on their heels. In the north, Ryabyshev’s 28th Army also burst out of the Volchansk salient and was making good progress against Hollidt’s XVII Army Corps.

At Paulus’s headquarters, the situation was chaotic. Messages received from forward units spoke of hordes of enemy tanks and infantry shattering the German line. The Army’s position was eerily similar to the events that had occurred just a few months earlier. Once again, some German units had disintegrated into a panicked mob as the Soviets overran their positions. Others fought an orderly withdrawal with Russian infantry and tanks swirling around their positions like wild dogs waiting for an opportunity to move in for the kill.

As the day progressed, Paulus’s situation maps showed tremendous gaps in the German lines. Arrows marking the progress of Timoshenko’s attack resembled skeletal fingers reaching out to grasp Kharkov. In a conversation between Paulus and von Bock, the 6th Army commander was urged not to counterattack too hastily and to wait until the situation further developed. Rain and overcast skies prevented aerial reconnaissance, and von Bock did not want Paulus to fritter away his reserves in uncoordinated attacks.

Paulus vacillated, but he was in no position to wait patiently. On the urging of his staff, the general scoured the rear areas for every available soldier to man blocking positions in front of the city. He also ordered retreating units to form strongpoints and attack the flanks of the Soviet thrust.

At higher headquarters, senior officers were taking note of the offensive, but on the opening day many viewed it as a strong local attack. In his diary, Halder wrote, “The enemy used 100 tanks in each attack (Izyum and Volchansk) and has scored considerable initial success.” He also noted that air units from the Crimean sector would be diverted to the Kharkov sector and that the 23rd Panzer Division had been ordered to stop refitting and advance to the front.

Von Bock Slowly Came to the Realization That the 6th Army was Fighting for Its Life

Most eyes had been on Gorodnyanskii’s assault during the opening hours of the offensive, with little attention being paid to what the Germans considered a spoiling attack from the Volchansk sector. It soon became apparent, however, that Paulus faced just as big a threat north of Kharkov, as Ryabyshev’s 28th Army sliced through the 294th Infantry Division. On the 294th’s left flank, von Schwerin’s 79th Infantry Division reported, “The enemy hitting our right flank with new masses of tanks, especially T-34s and KV-Is, which our antitank units can do nothing against.” By the end of the day, the 28th Army had advanced about 16 miles.

Von Bock had a rather cavalier attitude at first, advising patience and cautioning against uncoordinated counterattacks without air support. As more and more reports made their way to his Poltava headquarters, however, he and his staff came to the realization that the 6th Army was fighting for its life. The momentum of the Russian attacks from Izyum and Volchansk had carried the Soviets far behind the German main line of resistance, and the entire southern sector of the Eastern Front was in jeopardy.

Paulus was indeed in desperate straits, and his lack of experience in commanding front line troops began to show. As a staff officer, it had been his duty to point out the pros and cons of any given situation, laying all options on the table so that his commander could make a rational judgment. The Russian assault was an immediate threat that demanded decisive action, but Paulus seemed unsure as to what to do, now that he was in the position of commander.

While it is true that, with the urging of his staff, he had ordered counterattacks to slow the Russian advance, he seemed unsure of his next move. Should he hold Kharkov at all costs, or should he order a withdrawal to form a more stable line and protect his rear area and supply lines? If he stood fast, his entire army would be in danger of being encircled by the Russians. Pulling back would deny the Germans use of the Kharkov communications and supply hub, depriving the Wehrmacht of an important launching point for the upcoming Stalingrad offensive. Fortunately for Paulus, his opponent was also less than sure about how to continue.

Timoshenko was slow to exploit his initial success. He had a golden opportunity to smash the Germans completely on the 13th, but he let it pass by failing to commit his mobile reserves to the battle. The equivalent of 16 German battalions had already been destroyed, but faulty Soviet intelligence reports indicated that the Germans were massing a sizable force of tanks on the south flank of the Southwest Front. Therefore, throughout May 13 and 14, the mobile reserves, as well as available units from the South Front, remained in static positions waiting for an expected German attack.

Gorodnyanskii and Bobkin continued to urge their troops forward, hoping that Timoshenko would soon release his reserves. As in the winter campaign, many German hedgehog positions were bypassed as the assault troops pushed toward their objectives. Ryabyshev was also making good progress against the battered 294th Infantry Division, pushing the Germans back toward Kharkov.

The situation was now being monitored closely in Berlin. On May 13, Halder wrote, “In 6th Army’s sector, heavy attacks south and northwest of Kharkov supported by several hundred tanks. Serious penetrations.”

At von Bock’s headquarters, the staff of Heeresgruppe Süd was trying to formulate a plan of action. The planned Fridericus operation was obviously unfeasible, as 6th Army was having a tough time just staying alive, let alone counterattacking, and Generaloberst Hans von Salmuth’s 17th Army, which was to be the southern striking force of Fridericus, was not strong enough to attack the massed Soviet units in the bulge.

On the afternoon of the 14th, von Bock telephoned Berlin to explain his new plan. He told Halder and Hitler, “The situation on the right flank of 6th Army is bad. To the north (Volchansk), situation improved, largely because of the Luftwaffe.” He then explained that he wanted to strengthen a proposed attacking force by moving General der Kavallerie Eberhard von Mackensen’s III Panzer Corps and other elements of GeneralOberst Ewald von Kleist’s 1st Panzer Army northward.

Hitler responded by telling von Bock that he “suggested the possibility of an attack in the direction of Izyum. Not just on Izyum: from the left flank one can attack and cave in the enemy…. [There are] great opportunities through an attack on the enemy rear.” The outcome of the conversation was a revised Operation Fridericus that would deliver a strong blow on May 17 to the Soviet left flank, with the objective of cutting off the neck of the Izyum Bulge and trapping the Soviets inside.

On May 15, Soviet assault forces battered their way through the thin German defenses and took Krasnograd and Taranovka. Russian units from the 28th Army were within 12 miles of Kharkov before they were stopped by counterattacks by elements of the 3rd and 23rd Panzer Divisions. The following day Russian reconnaissance units came to within 25 miles of von Bock’s headquarters at Poltava.

Unbelievably, Timoshenko still withheld his mobile reserves! Any German panzer commander worthy of the name would have seen the opportunities provided by the initial breakthrough and would have pushed his mobile forces into the fray on the 13th. Instead, Timoshenko still refused to commit. He would wait one more day before sending the second echelon into the battle, but by then it would be too late.

While Timoshenko vacillated, von Kleist’s divisions streamed northward. In the vanguard were Generalleutnant Hans Valentin Hube’s 16th and Generalmajor Friedrich Kühn’s 14th Panzer Divisions. Close on their heels were Oberst Otto Kohlermann’s 60th Motorized Infantry Division, Generalmajor Hubert Lanz’s 1st Gebirgs (Mountain) Division, and Generalleutnant Werner Sanne’s 100th Leicht (Light) Division. By the evening of the 16th, the panzer divisions had arrived on the left flank of the 17th Army, with the other divisions still moving up. In total, von Kleist would have a combined force of two panzer, one motorized, and eight infantry divisions to use in his attack.

The Germans Quickly Learned that Destroying Command Tanks Left the Remaining Russian Tanks Unable to Communicate

Just before dawn on the 17th, the Germans struck the southern flank of the Soviet salient. With the 16th Panzer in the lead, the attack hit the infantry units of the 9th and 57th Armies. Brushing aside the Soviet infantry, the panzers moved forward to meet the Russian tank units. Many of the enemy tanks were lighter models, which soon fell victim to the German gunners. Although the guns and armor of the panzers were no match for the heavier Soviet T-34s and KV-Is, Hube’s panzers managed to close quickly with the Russians and engaged them at close range, negating the Russian advantage.

The Germans also used another advantage to their benefit. Only Soviet tank unit commanders had a radio in their vehicles to report the situation to higher commands and to receive orders. Other tanks in the unit communicated by hand signals or flags, which was next to impossible in combat situations. German tankers soon learned to recognize and destroy the command tank. Once eliminated, the other Russian tanks were left on their own, unable to transmit or receive orders.

While the panzers were wreaking havoc on the Russian tank formations, German infantry pushed through the remaining Soviet defenses. Lacking tanks, many of the attacking infantry units interspersed self-propelled 20mm antiaircraft guns among their platoons. As the 20mm shells swept their positions, the Soviets were also hit by artillery fire and aircraft bombs from the Luftwaffe’s IV Fliegerkorps.

Although they defended themselves bravely, the Russians were no match for von Kleist’s formations. By nightfall, German units were on the bank of the Donets, having advanced some 25 miles during the first day of the attack. North of Kharkov, the 3rd and 23rd Panzer Divisions, now up to strength, started to push back the 28th Army, encircling Soviet units and then destroying them with supporting infantry columns.

Timoshenko realized that he was in serious trouble. Even though his mobile reserves were finally being committed, they were deployed individually instead of in mass formations and were rudely handled by the German panzers roaming freely behind the Russian lines. Calling Moscow, Timoshenko frantically pleaded for reinforcements, but his request was denied. He was also told, in no uncertain terms, that withdrawal from the salient was not an option.

On May 18, the German attack continued in temperatures that approached 90 degrees F. Arriving from the Crimean Sector, Stuka dive-bombers and high-level bombers from GeneralOberst Wolfram von Richtofen’s VIII Fliegerkorps began pounding the Soviets. By now, Timoshenko had committed his 21st and 23rd Tank Corps to the battle, but the Russian units took a terrific beating from the air as they attempted to reach the front. Von Richtofen, a cousin of the famous Red Baron, was known as an aggressive commander, and his men followed his example in their unrelenting attacks.

The 57th and 9th Armies continued to fall back, pursued by German panzer and motorized columns. Elements of von Hube’s 16th Panzer Division broke off from the main attacking force. Blasting their way through startled Soviet units, by noon the combat group reached Donetskiy, the main crossing point in the area of the Donets River. A few hours later, the panzers were fighting in the suburbs of Izyum.

A huge gap had been torn in the southern flank of the Soviet salient. Timoshenko ordered his 5th Cavalry Corps and an infantry division to counterattack, but the Russian forces were decimated by artillery fire and the ever-present Luftwaffe. The counterattack did little to impede the German advance. By evening, the 17th Army’s 101st Leicht Division (Oberst Friedrich Diestel) and 257th Infantry Division (Oberst Karl Püchler) had fought their way to the Donets, with some elements even crossing to the eastern bank.

Although there are conflicting accounts concerning Timoshenko’s reaction to the day’s events, Soviet sources agree that both Khrushchev and Bagramyan telephoned Stalin to ask him to halt the offensive and pull back. Stalin refused to talk to either of them, but through an intermediary from the State Defense Committee they were both told to “let everything remain as it is.”

However, things did not remain as they were. The 28th Army, already mangled by the 3rd and 23rd Panzer Divisions, began to withdraw some of its battered units back to Volchansk. At the head of Ryabyshev’s salient, the two panzer divisions and remnants of the 294th Infantry Division stood fast, repelling all attacks while the 79th and 297th Infantry Divisions harassed the flanks of the 28th Army.

About midday on the 19th, Stalin finally decided to call off the offensive. The strength of the German attack and conversations with his most trusted advisers persuaded him of the futility of continuing. Group Bobkin and the 6th Army were ordered to about-face and head back to the Donets, but it was already too late for most of the more than 250,000 Soviet soldiers inside the bulge.

Action slowed somewhat during the rest of the day, with the 16th Panzer sitting in Izyum and the 257th Infantry and 101st Leicht Divisions expanding their conquest of the eastern bank of the Donets. Most of the 57th Army was now trapped inside the bulge and the 9th Army had been totally defeated, many of its units being completely unfit for further combat. Von Kleist also committed Kühn’s 14th Panzer Division to take the town of Petrov- skoye, about 20 miles west of Izyum, which it successfully did.

Of the More Than 250,000 Soviets Inside the Pocket, Less Than One in Ten Escaped

With the 6th Army and Group Bobkin streaming back to the river, it was essential that the Germans close the neck of the Izyum bulge. On May 20, Kühn was ordered to take the river crossing at Protopopovka, about 10 miles north of Petrovskoye. Kühn accomplished his mission, reducing the distance between his division and Hollidt’s LI Army Corps to a mere 12 miles. The 14th and 16th Panzer Divisions had done a remarkable job in creating a dagger like bridgehead within the Soviet salient, but they needed infantry support to withstand the retreating Russian forces that were approaching from the west.

Now that Ryabyshev’s 28th Army was in full retreat, von Bock planned to use part of the 6th Army to help close the gap between Protopovskoye and Balakleya, where Deboi’s 44th Infantry Division was stationed. He ordered Paulus to shift the 3rd and 23rd Panzer Divisions to Balakleya, where they would join the 44th in a southerly attack. While Paulus’s panzers moved into position, von Kleist brought up his infantry for a push to reinforce his panzer divisions inside the pocket.

On May 22 the fate of two Soviet armies and Motorized Group Bobkin was sealed when Kühn’s 14th Panzer Division hooked up with elements of the 23rd Panzer and 44th Infantry Divisions. The neck of the Izyum bulge was now closed, with the 6th and 57th Armies and Group Bobkin trapped inside. The time for von Kleist to commit the rest of his infantry divisions was at hand.

Von Kleist’s infantry poured into the pocket on the 23rd to support the panzers and form a barrier to meet the retreating Russians. While the 14th and 16th Panzer Divisions, plus the 257th Infantry and 101st Leicht Divisions, stopped Timoshenko from bringing more troops into the salient from the east, the 60th Motorized, 100th Leicht, 1st Gebirgs, and the 389th (Generalleutnant Eccard von Gablenz) and 384th (Generalleutnant Erwin Jaenecke) Divisions formed a wall to the west.

With pressure on the 6th Army relieved, Paulus was ordered to push his divisions forward, compressing the Soviet pocket. As Paulus’s divisions advanced, the Russians fought like demons as they threw themselves against the Germans blocking their retreat.

The next few days were a scene from hell. Wave after wave of Soviet infantry attacked the German line, only to be cut to pieces. The Luftwaffe added to the carnage, bombing and strafing Russian columns as they formed up to attack. Hundreds lay dead in front of von Kleist’s infantry positions, but still they came, urged on by their commanders and commissars.

One Russian attack succeeded in breaching the line held by the 60th Motorized and 389th Infantry Divisions. As the Soviets forged ahead, making for the Donets, they ran headlong into the 1st Gebirgs Division, which had been kept in reserve to counter such a situation. Lanz’s Gebirgsjäger met the enemy with a withering fire, slaughtering the Red Army soldiers.

By May 28, it was all over. Generals Gorodnyanskii, Bobkin, Podlas, and Kostenko, the deputy commander of the Southwest Front, lay dead with their men. Of the more than 250,000 Soviets inside the pocket, less than one in 10 escaped. Seven cavalry divisions, 27 rifle divisions, and 14 motorized and tank brigades were destroyed, and more than 200,000 prisoners were taken. Thousands more lay dead on the battlefield. The Germans counted over 1,200 tanks and 2,000 guns destroyed or captured. German casualties were placed at about 20,000 killed, wounded, or missing.

Postwar Soviet analysis of the battle blamed lack of cooperation and coordination between the Southwest and South Fronts, underestimating the problems of protecting the flanks of the salient, and tremendously defective command control of forces for the failure of the operation. In 1956, Khrushchev laid the blame for the debacle squarely on Stalin.

Perhaps the most extraordinary outcome of the battle was the way that Paulus was viewed in Berlin. Instead of being reprimanded or relieved for his indecision and his dismal lack of imagination during the opening phase of the battle, he was awarded the Knight’s Cross by Hitler and hailed as a hero in the German press.

His actions during the course of the battle were but a precursor to what would happen at Stalingrad, when the victorious 6th Army was wiped out. Many of the generals and divisions that had fought in the Izyum bulge would have their fate sealed in Stalin’s city.

Pat McTaggart is an expert on World War II on the Eastern Front. He writes from his home in Elkader, Iowa.

And once again the Russians have been ejected from Izyum and the nearby localities, this time by the Ukrainian Army.