By Pat McTaggart

The German Army found itself facing a massive challenge in the spring of 1944, just months before its total disaster at the Battle of Brody — they were facing the possibility of a war on three fronts. In 1943, the Allied invasion of Italy diverted several sorely needed divisions from the Eastern Front, and the inevitable invasion of the continent by Allied forces in Great Britain tied down German divisions spread from the south of France to Norway.

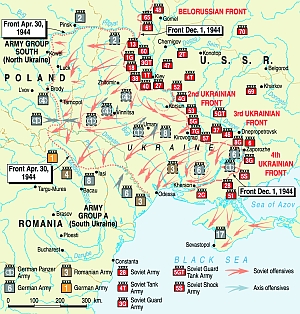

On the Eastern Front, things were going from bad to worse. In the north, the siege of Leningrad was finally lifted when a massive Soviet offensive struck Heeresgruppe Nord (Army Group North) on January 14. During the offensive, three Red Army fronts slashed through German positions from Leningrad to Velikiye Luki, rupturing the main line in several places.

German forces, plagued by sub-zero temperatures and deep snow, struggled toward the west as Russian armored and mechanized units surged forward in the hope of surrounding and destroying them. It was a close thing for the Germans, but a new line of resistance was finally established, anchored in the middle by Lake Peipus.

In some places, the offensive had pushed German forces back more than 150 miles. Casualties had been enormous on both sides, and several German divisions had lost most of their heavy equipment. Soviet equipment losses were also high, but they were soon replaced from the now fully organized Russian industrial centers. Replacements for the dead and wounded also arrived throughout the spring to fill the gaps left by the heavy fighting.

The German front in southern Russia also suffered a series of hammer blows during the winter and into the spring of 1944. In December 1943 and January 1944, the 1st and 2nd Ukrainian Fronts attacked Field Marshal Eric von Manstein’s Heeresgruppe Süd (Army Group South) from their strong bridgeheads on the German side of the Dniepr River.

Blizzard conditions hampered German counterattacks as the Russians continued to drive on the Dniester and Bug Rivers. General Eberhard Raus’s 1st Panzer Army found itself cut off by the rapid Soviet advance, but it fought a brilliant rear-guard action behind the Russian lines. Supplied by airlifts, Raus conducted a fighting withdrawal and eventually made it safely out of the Red Army’s grasp.

Farther south, Field Marshal Ewald von Kleist’s Heeresgruppe A (Army Group A) was forced to retreat in the face of an attack from the 3rd and 4th Ukrainian Fronts. As the Germans pulled back, elements of the 6th Army and 8th Army were surrounded and destroyed. Von Kleist was forced to abandon the important Black Sea port of Odessa on April 10, while his 17th Army, which had been trapped in the Crimea since late December, was destroyed in early May.

Farther south, Field Marshal Ewald von Kleist’s Heeresgruppe A (Army Group A) was forced to retreat in the face of an attack from the 3rd and 4th Ukrainian Fronts. As the Germans pulled back, elements of the 6th Army and 8th Army were surrounded and destroyed. Von Kleist was forced to abandon the important Black Sea port of Odessa on April 10, while his 17th Army, which had been trapped in the Crimea since late December, was destroyed in early May.

By the time the Soviet offensive ran out of steam, most of the Ukraine had been reclaimed and the Red Army had made inroads into Germany’s ally, Romania. The new front now stretched from Odessa, north to about 50 miles south of Brest-Litovsk.

As the result of the Soviet attacks in the north and the south, Field Marshal Ernst Busch’s Heeresgruppe Mitte (Army Group Center) now formed a vast bulge that encompassed most of Poland and part of western Belorussia. German commanders inside the bulge watched nervously as their comrades to the north and south were relentlessly pushed back by the Russian offensives. They knew that it was only a matter of time before it was their turn.

The onset of the muddy season gave the Germans a much needed respite from the pounding they had taken. While the Russian Front commanders occupied themselves with reforming and reinforcing their combat-weary divisions, the Oberkommando des Wehrmacht (OKW—the German High Command of the Armed Forces) scrambled to find replacements for the men that had been lost. Several new divisions, many not yet fully trained or equipped, were also sent to the front to meet the expected resumption of Red Army assaults once the ground was firm enough.

One of those newly formed divisions was the 14th SS Freiwilligen Division “Galizien” (14th SS Volunteer Division “Galicia”). Galicia, basically the western half of the Ukraine, had been part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire prior to the end of World War I. From 1917 to 1920, the Ukraine was an independent state, but it was caught in the crossfire of the Russo-Polish War, which ended its brief life.

At the end of hostilities, the western Ukraine fell under Polish control, while the Soviet Union swallowed up the eastern half of the country. The fiercely independent Ukrainians fought a shadow war against both countries, but with their homeland already torn in half, there was little they could do against the military might of either nation.

With the onset of World War II, Galicia was once again plagued by invasion—this time from the Soviet Union. The reign of terror that followed lasted almost two years, and it cost the lives of thousands of Ukrainian nationalists, with thousands more being deported to Soviet labor camps.

The advent of Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union, brought the Ukraine a new conqueror. In many instances, German units were greeted as liberators with the traditional bread and salt as they passed through Ukrainian villages and towns.

Luckily for the Ukrainians, the man responsible for governing Galicia, SS Brigadeführer (brigadier general) Otto Wächter, was more enlightened than most of the German administrators in the East. He handled the Ukrainians under his control carefully, seeking cooperation from the population instead of using the heavy- handed methods practiced by his peers. For the most part, Galicia remained one of the most peaceful of the occupied Eastern territories during the early years of the war.

The 14th SS Division Showed Promise, but It Would Take Months Before They Were Ready to Face the Red Army

After the debacle at Stalingrad, even the most racially driven Nazis began to realize that something had to be done to replace the hundreds of thousands of German troops that had been lost during the previous 18 months. Wächter seized the opportunity by suggesting to Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler that Ukrainians could be used to fill the ranks of the Waffen SS. After some thought, Himmler agreed that the already existing Galician Police Regiment could be used as the nucleus for a combat division.

Between 70,000 and 100,000 men stepped forward to volunteer for the new division. Those who were not chosen for the 14,000-man unit, but were still physically acceptable, were incorporated into five new regiments of police. In the summer of 1943, the unit underwent training in the General Government (what was now left of Poland). April 1944 found the unit at Neuhammer, Silesia, for more training.

Many of the Ukrainian officers in the division had served in the Austro-Hungarian Army during World War I. The native noncommissioned officers of the division were a somewhat undistinguished group, and the enlisted men, although enthusiastic, had little or no military training at all. German officers and NCOs formed the cadre of the division, but many of them were substandard soldiers that were considered expendable by the units that had supplied them. In the opinion of many of the officers that observed the division at the training grounds, the 14th showed promise, but it would take several more months to bring it up to the standard necessary to meet the Red Army in combat.

The commander of the 14th SS Division “Galizien” was SS Brigadeführer Fritz Freitag, a man who was disliked by many of his contemporaries. Described as an abrasive opportunist, Freitag was born in Allenstein, East Prussia, in April 1894. He was a volunteer in World War I and joined the East Prussian Security Police following the conflict.

On September 1, 1940, Freitag joined the SS. In 1941, he was on the staff of the 1st SS Brigade, and he later served with the SS Cavalry Division, the 2nd SS Motorized Infantry Brigade, and the SS Police Division, where he was the acting division commander. After attending a division commander’s course, he took over the reins of the “Galizien” Division in April 1944.

While the division continued to train, the war in the East began to intensify once again. Field Marshal Busch was becoming increasingly concerned about the position of his Heeresgruppe Mitte. Logically, the Heeresgruppe should have been pulled back to straighten its lines, which would also provide a reserve of divisions that could be used to parry any Soviet breakthrough that might occur when, as everyone presumed they would, the Russians began their summer offensive.

Logic, however, was not in Hitler’s vocabulary in 1944. He demanded that every foot of conquered soil be held, no matter what the cost. Looking at large maps of the Eastern Front, he totally disregarded the realities of the military situation. A Soviet attack must surely come, but where and when would the offensive begin? In the north, a knockout blow would bring the Baltic States under Russian control and would almost certainly cause the Finns to sue for peace. The south offered rich possibilities with the Romanian and Hungarian oilfields as the prize. In the center, Heeresgruppe Mitte also offered a tempting target with its overstretched lines.

In Moscow, the question was not where to strike, but when to strike. The bulge containing Heeresgruppe Mitte was just too tempting to pass up. Since mid-April, Stavka (the Soviet High Command) had been planning a massive pincer attack designed to crush the Heeresgruppe. The plan would be skillful, both in its conception and in its execution.

German intelligence, eyes on the northern and southern fronts, declared that the area north of the Pripyat Marshes would remain quiet. Therefore, while Berlin hastened to gather meager reserves to meet the expected offensives on either side of Heeresgruppe Mitte, Busch was basically left to make do with what he had.

While the Germans looked elsewhere for signs of an impending attack, the Russians were conducting a masterfully disguised buildup opposite Busch’s Heeresgruppe. The Red Army had always been superb at camouflage and deception, but the Soviet Front commanders that would lead the attack outdid themselves in preparing for the assault.

The Russians also had a second plan ready depending upon the initial results of the attack against Heeresgruppe Mitte, and an offensive was also scheduled against Field Marshal Walter Model’s Heeresgruppe Nord Ukraine. It seems that Hitler did his level best to confound historians by constantly renaming Heeresgruppen (army groups). After Hitler dismissed von Manstein in late March, he divided Heeresgruppe Süd into Heeresgruppen Nord Ukraine and Süd Ukraine in April.

The Russians also had a second plan ready depending upon the initial results of the attack against Heeresgruppe Mitte, and an offensive was also scheduled against Field Marshal Walter Model’s Heeresgruppe Nord Ukraine. It seems that Hitler did his level best to confound historians by constantly renaming Heeresgruppen (army groups). After Hitler dismissed von Manstein in late March, he divided Heeresgruppe Süd into Heeresgruppen Nord Ukraine and Süd Ukraine in April.

Model was one of Hitler’s favorite generals. He could get away with things, including unauthorized withdrawals, that would have ended most Wehrmacht generals’ careers. His Heeresgruppe consisted of the 1st and 4th Panzer Armies and the 1st Hungarian Army.

Heeresgruppe Nord Ukraine occupied a defensive line running from Kovel in the north through the southern Pripyat Marshes and the eastern bank of the Bug River to the Romanian border in the south. A secondary defensive line, the Prinz Eugen position, lay about 10-15 miles behind the main line positions.

Ever on the move, Model visited his various corps commanders, giving advice as well as taking suggestions about what could be done to strengthen the German line. After reading German intelligence estimates concerning the areas where Russian attacks could be expected in the coming summer, Model asked Hitler to transfer the LVI Panzer Corps from Heeresgruppe Mitte to Heeresgruppe Nord Ukraine.

Appealing to Hitler’s distaste for defensive warfare, Model proposed using the corps for a preemptive strike against the Soviet forces opposing him. Although Model’s attack would never be carried out because of swift-moving events elsewhere, the LVI Panzer Corps was passed from Busch’s to Model’s control. With it went 15 percent of Heeresgruppe Mitte’s divisions, 33 percent of its heavy artillery, 50 percent of its tank destroyers, and 23 percent of its self-propelled assault guns. It was a move that would cost Busch dearly.

Meanwhile, events in the West had taken an ugly turn for the Wehrmacht. On June 6, Allied forces poured ashore on the Normandy coast. All eyes shifted toward the savage battle in the Normandy hedgerows that would decide the fate of Western Europe. Pushed to the limit, German commanders in the West begged for reinforcements and supplies, which were being blasted into oblivion because of the enormous Allied air superiority.

As the Allies expanded their bridgehead on the European continent, the Soviets struck in the East. Stavka chose June 22, the third anniversary of the German invasion of the Soviet Union, to begin the assault against Heeresgruppe Mitte.

After a devastating barrage, the Red Army struck with overwhelming strength. German divisions literally disintegrated in the human and steel storm that blew from the East. Within a week, Busch’s front had crumbled, and tens of thousands of German troops were fleeing for their lives.

German commanders on either side of Heeresgruppe Mitte listened nervously to reports of the rout. If something was not done to stop the Soviet steamroller, their own flanks would be untenable. Knowing Hitler’s penchant for standing fast, the German generals not yet under attack knew that they would face the impossible dilemma of disobeying Hitler’s no-retreat order or sacrificing their men for no sound military purpose.

Setting the Stage for the Battle of Brody

Keeping an eye on the north, Model kept up his tours of the front. One of the corps under his command was General Arthur Hauffe’s XIII Army Corps, which was part of the 1st Panzer Army. Born in 1891, Hauffe served in the Kaiser’s Army in World War I and continued his service in postwar Germany’s 100,000-man Reichswehr. During the interwar period, Hauffe assumed several staff positions, and in the first two years of World War II he was chief of the general staff of the XXV Army Corps and the XXXVIII Panzer Corps.

Following a one-and-a-half-year posting as the chief of staff to the German military mission to Romania, Hauffe took command of the 46th Infantry Division in February 1943. Five months later, he replaced General Friedrich Siebert as commander of the XIII Army Corps.

Hauffe’s corps defended a stretch of the front about 60 miles east of L’vov. The terrain was fairly flat—good tank country—and the German divisions in the sector would have to rely on man-made defenses and obstacles to stop any Soviet attack.

One of the few significant landmarks in the area was the Ukrainian town of Brody. A rail net, one of the few in the sector, connected the town with L’vov, and several roads and trails also merged there. If a Russian attack were to occur, the town would certainly be one of the Red Army’s main objectives. The ensuing Battle of Brody during the Lvov–Sandomierz Offensive would help change the fate of the German offensive along the Eastern Front.

Heike Hoped to get His Troops Basic Combat Training Before Galizien’s Trial by Fire, but This was a Forlorn Hope

Searching for more units to bolster the lines on either side of Heeresgruppe Mitte, orders were sent in late June for the Galizien Division to suspend its training in Silesia and prepare for departure to the Eastern Front. Train after train funneled the division eastward toward an uncertain future. As advance elements of the division arrived in the Ukraine, Army Major Wolf-Dietrich Heike, the division’s chief of staff, learned that the Galizien was to deploy in secondary positions behind the main line occupied by Hauffe’s XIII Army Corps near Brody.

Searching for more units to bolster the lines on either side of Heeresgruppe Mitte, orders were sent in late June for the Galizien Division to suspend its training in Silesia and prepare for departure to the Eastern Front. Train after train funneled the division eastward toward an uncertain future. As advance elements of the division arrived in the Ukraine, Army Major Wolf-Dietrich Heike, the division’s chief of staff, learned that the Galizien was to deploy in secondary positions behind the main line occupied by Hauffe’s XIII Army Corps near Brody.

Heike had hoped that the Galizien’s baptism of fire would come slowly with the division defending a relatively quiet sector so that the troops could gain some basic combat experience. A quick look at the map told Heike that his was a forlorn hope. The XIII Army Corps was a plum waiting to be picked, and the Galizien’s positions could do little to stop a Soviet offensive once it started in that sector.

Major Heike’s arrival at Hauffe’s headquarters came as a surprise to the corps commander. Hauffe had never heard of the Galizien Division, and Heeresgruppe Nord Ukraine had obviously failed to inform his headquarters that the division was on its way. Heike showed Hauffe his orders and told the general that his division had been assigned to the sector around Brody. After discussing the situation in the corps sector with Hauffe’s chief of staff, Heike set out to the division assembly point.

Trains carrying the division began arriving in the assigned sector during the next few days. What was supposed to be a defensive line consisted of a few trenches and gun pits with no overhead cover. Heike put the men to work immediately. New trenches needed to be dug, and key positions had to be fortified. It would take time to make the line defensible, but time was something the Galizien did not have.

Across the lines of Heeresgruppe Nord Ukraine, General Konstantin Rokossovsky’s 1st Belorussian and General Ivan S. Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Fronts prepared for battle. The news from the commanders fighting against Heeresgruppe Mitte was good, and the two Soviet generals were anxious to join the fray. Konev, facing the 1st Panzer Army and part of the neighboring 4th Panzer, had a powerful force under his command. His Front included three tank armies (1st Guards, 3rd Guards, and the 4th), two cavalry-mechanized groups under Lt. Gen. V. K. Baranov and Lt. Gen. S.V. Sokolov, and seven infantry armies (1st Guards, 3rd Guards, 5th Guards, 13th, 18th, 38th, and 60th). There were also several independent tank, artillery, and mechanized units incorporated into the 1st Ukrainian Front to give it an added punch.

While Konev and Rokossovsky waited impatiently for the order to attack, the battle in Heeresgruppe Mitte’s sector caused Hitler to become slightly more flexible with some of Model’s suggestions concerning Heeresgruppe Nord Ukraine’s position. In late June, just weeks before the Battle of Brody, the Führer agreed that both Kovel and Brody would no longer be designated “fortified places” (a designation that was a literal death sentence to any units charged with defending them).

In the midst of Model’s attempts to give his Heereesgruppe a better position from which to meet a Soviet attack, he was recalled to Berlin and transferred to the Western Front to try and stabilize the situation there. His replacement was Generaloberst (colonel general) Josef Harpe, a competent officer with a background in armor. Harpe was able to implement several of the redeployments that Model had started, but he did not have the influence with Hitler to continue past that point.

Hitler allowed the 4th Panzer Army to abandon Kovel altogether in early July and to move its line westward about 15 miles, which straightened the front. A week later, he allowed the 4th Panzer Army to shorten its line around Torchin.

Watching the Germans disengage was too much for Konev. Although the attack against Heeresgruppe Nord Ukraine was scheduled to begin on July 14, the fiery Soviet general jumped the gun by one day, hoping to catch the Germans flat footed as they moved their divisions back to their new positions.

Konev was born in 1897 and served in the Czar’s Army during the brutal battles on the Russian Front in World War I. In 1918, he joined the Communist Party and the Red Army, serving as a political commissar during the Russian Civil War. The interwar years gave Konev a chance to further his military education and advance in rank. He was a divisional commander and was acting commander of the Trans-Caucasian Military District at the time of the German invasion.

In the first crucial year of the war, Konev commanded the Kalinin Front, defending the vital approaches to Murmansk. When the Soviets regained the initiative in 1943, Konev proved himself as a skillful and resourceful commander on the offensive. His reputation for conducting successful operations came close to that of the master himself—Marshal Georgi Zhukov.

The July 13 attack surprised German and Russian commanders alike. The Soviet generals had everything coordinated for a July 14 assault, and timetables had to be thrown out the window as orders came for the early attack.

Konev struck the retreating right flank of the 4th Panzer Army. Because of the premature attack, his main strike force, General V.N. Gordov’s 36th Army, got off to a rather sluggish start. The disengaging German divisions had mostly occupied their assigned secondary front line positions, and Gordov’s men ran into a wall of fire as they approached the enemy.

The objective for Gordov was the town of Rava Russkaya, about 50 miles to the west. As the Soviets hit the secondary German line, Gordov’s divisions slowed to a crawl. The Red Air Force, also upset by the pushed up attack, was slow to take to the air but finally joined the battle by midday.

Although most of the German divisions held fast, one of the units on the 4th Panzer Army’s right flank began to break. General Walter Nehring, a former commander of the Afrika Korps, was in temporary command of the Panzer Army. He ordered one of his panzer units forward to bolster the crumbling division, but the Red Air Force intervened, making the movement a slow and dangerous affair.

Forward Positions Were Obliterated, and the Red Air Force, with Virtually No Opposition, Roamed the Battlefield at Will.

Ever the opportunist, Konev threw General N.P. Pukhov’s 13th Army into the battle once weak points were found in the German line. A savage battle ensued around the town of Gorokhov, causing heavy losses on both sides. By the end of the day, the town was in Soviet hands, and Pukhov’s divisions were moving to help Gordov’s men batter the Prinz Eugen position.

In the XIII Army Corps sector, the opening barrage of Konev’s assault was heard by everyone from Hauffe down to the lowest ranking enlisted man. The commanding general went over his maps and checked the latest intelligence reports again and again. Hauffe had no illusions about what was facing him, and his chief of staff, Oberst (Colonel) Curt von Hammerstein, agreed that the situation looked extremely bleak.

The XIII Army Corps left flank was held by General Johannes Nedtwig’s 454th Sicherheit (Security) Division. Next came General Gerhard Lindemann’s 361st Infantry Division. Korps Abteilung C (an ad hoc formation made up of the remnants of the 183rd, 217th, and 361st Infantry Divisions) was on Lindemann’s right. The unit was commanded by General Wolfgang Lange, and it had the strength of a weak infantry division. General Otto Lasch’s 349th Infantry Division, another weak unit, held the right flank. The final unit under Hauffe’s command, the Galizien Division, occupied the secondary line about eight miles west of Brody.

Now the Battle of Brody was set to begin: a blistering Soviet barrage on July 14 sounded the death knell for Hauffe’s army corps. Forward positions were obliterated as the shells hit home, and the Red Air Force, with virtually no opposition, roamed the battlefield at will. With the successes of the previous day still having their effect on the Germans, Konev did not hesitate to commit his second-echelon forces for a general attack.

Colonel General P.S. Rybalko’s 3rd Guards Tank Army was ordered to support Pushkov’s continuing attack in the north. The Soviet attack was slowed by elements of the 16th and 17th Panzer Divisions, which were fighting fiercely to stem the assault, but other formations were able to make better headway. A two-pronged attack was now underway, threatening to destabilize the entire front of the 1st Panzer Army.

In Hauffe’s sector, Konev struck the Germans at their weakest points, the divisional boundaries. Lasch’s 349th was hit at its juncture with the neighboring 357th Infantry Division. Another Russian attack sliced through the 96th Infantry Division in an adjacent sector. Konev poured more units through the gap, extending the penetration to about 10 miles behind the German lines.

At the junction of the 454th Sicherheit Division and the 361st, another attack resulted in a break that severed communications between the two divisions. Both units threw their almost nonexistent reserve into the gap and managed to stop the Russians from advancing farther after heavy fighting. The situation was extremely fluid along Hauffe’s entire front as the Soviets searched for further weak points in the German defenses.

At the headquarters of the Galizien Division, orders were received to go to full alert. There was only one problem—neither Brigadeführer Freitag nor Major Heike was at the headquarters. Both men had been at the 454th headquarters when the Soviet attack hit, and they were delayed until midmorning before they could return to their own division. When they finally arrived, they found orders waiting that directed the division to form up immediately and head southwest to seal a hole in the line and also to engage Soviet units that had broken through.

The lead regiment of the division soon met groups of retreating German infantry, some in total disarray. This did nothing to calm the nervousness already felt by many in the untested unit. Discipline prevailed, however, and the Ukrainians kept fixed on their goal.

A chance meeting with a Red Army tank unit gave the Galizien its first taste of battle. Using satchel charges and bundles of grenades, elements of the lead regiment were able to drive back the Soviets, who left several smoldering tank hulks on the field. Its business finished, Freitag ordered the regiment and the division to continue their march toward its objective.

The real baptism of fire for the entire division took place on the afternoon of July 14 when the Galizien hit the flank of a Soviet assault unit that had found a weak point in the Prinz Eugen position. Freitag’s 30th Waffen Grenadier Regiment was first into battle. It initially made progress, but the appearance of the Red Air Force caused the regiment to retreat with substantial casualties.

Although the Russians had paused to regroup after stopping the attack, neither side had gained a decisive advantage. With the arrival of Freitag’s 29th and 31st Waffen Grenadier Regiments, a stalemate developed. As night fell, both the Ukrainians and the Russians settled in to await the next day.

For the most part, Hauffe’s army corps and the rest of the German forces facing Konev had managed to prevent a general breakthrough that would have resulted in disaster for the entire panzer army. German forces were holding on, but they were vastly outgunned and outmanned. The Red Air Force and Red Army artillery had caused huge casualties among the Germans, and some of the previously under- strength battalions were now down to company size. With no relief in sight, Hauffe and the other corps commanders waited with great trepidation for Konev’s next move.

On July 15, Konev ordered further probing attacks along the length of the 1st and 4th Panzer Armies’ fronts, hoping to find more weak spots. Soviet units that had already broken through were roaming behind the German lines, forcing German commanders to squander their reserves in attempts to intercept and destroy the marauding enemy.

A limited counterattack stopped the Soviet 38th Army and actually forced it to retreat a small distance. In the 60th Army’s sector, however, Red Army engineers, supported by tanks and infantry, managed to make a small break in the German line.

Throughout the 15th, Freitag’s Galizien Division was in constant contact with the Russians it had met the previous day. Both sides were fighting furiously, and casualties mounted as the Ukrainians and Russians engaged in hand- to-hand combat. The chaotic fighting caused units to lose communications with each other, and the Ukrainians, afraid that they would become isolated, gradually began to pull back in small groups.

As more and more men began retreating, company and battalion officers did their best to keep the retreat from becoming a rout. The Soviets sensed victory, but the Galizien was finally able to form a cohesive line a few miles from the main battle area. Calmed by their officers, the Ukrainians were able to blunt the enemy attack, which, if successful, could have spelled disaster for the division.

Konev studied his maps carefully into the early morning hours of the 16th. The breaches in the German line were small, and it would take valuable time for the Red Army infantry to widen the gaps. Moving decisively, Konev sent word to Colonel General M.E. Katukov’s 1st Guards Tank Army to move through the gaps in the 4th Panzer Army’s lines without infantry support. The move caused those units of the panzer army that had still been holding out in front of the Prinz Eugen position to start a fighting retreat toward that line.

In the 1st Panzer Army’s sector the front held more or less firm. The action to the north caused Raus to issue orders for a withdrawal to begin the following day. During the 16th, the front line divisions were taxed to the limit, fending off Russians attacks and, at the same time, preparing to move to new positions.

With the Prinz Eugen Line No Longer an Option for the Germans, the 4th and 1st Panzer Armies Found Themselves Fighting for Their Lives

The German withdrawal started well enough, but a fighting retreat is a plodding affair. With Katukov’s 1st Guards Tank Army now making good progress against the 4th Panzer Army, Konev unleashed Rybalko’s 3rd Guards Tank Army, which had been pulled out of the line after supporting the infantry attacks on the 14th. Like Katukov’s units, Rybalko’s tanks and mechanized infantry slipped through the still narrow gaps in the 1st Panzer Army line. The two Guards Tank armies now formed the prongs of a massive pincer, inexorably moving toward each other.

By now, the Prinz Eugen line was no longer an option for the Germans. Both the 4th and 1st Panzer Armies were literally fighting for their lives. Konev’s tank armies had outflanked the German position, and infantry units were pouring through the gaps that were opened by the two cavalry-mechanized groups that had just been committed to the attack.

Red Air Force fighters and ground attack aircraft limited the effectiveness of the armored units left to the German commanders, but when the panzers were able to face Soviet tanks, they managed to put up a spirited defense. A Kampfgruppe (Combat Group) of the 8th Panzer Division managed to destroy several Russian tanks in the XIII Army Corps’ sector, but the Soviets always seemed to have more replacements to continue the push forward.

Konev countered the German armor by releasing Colonel General D.D. Leliushenko’s 4th Tank Army. The fresh units rushed forward to meet their opponents, but local counterattacks by German armored and infantry forces in neighboring sectors caused Leliushenko to order several battalions to rush to the aid of the 60th Army, which was suffering the brunt of the enemy action.

In the Galizien sector the situation continued to be confused. The division, especially the 30th Regiment, had been badly mauled during its brief life at the front. While the 30th regrouped, the other two regiments of the division manned positions that effectively blocked further Soviet advances in the Sasiw and Taseniw valleys.

Although German blocking positions slowed Konev’s forces in some areas, they could do nothing to change the overall position of the XIII Army Corps. The Soviet armored pincers were just too strong, and the following infantry was gradually able to overwhelm German strongpoints bypassed by the tanks. Nedtwig’s 444th Sicherheit Division was slowly disintegrating, and Korps Abteilung C was down to battalions instead of regiments because of the heavy fighting.

As the dismal reports kept coming into Hauffe’s headquarters, a sense of despair gripped his staff officers. There was little that they could do as the situation maps showed the Russian armored thrusts spreading like the tendrils of some horrific monster, and some were already burning documents in anticipation of what was to come.

At Freitag’s headquarters, the Galizien received word that there were no forces available to repel Red Army units that had broken through northwest of Brody. The SS general looked at his chief of staff as Heike read the report. Both men knew that the information spelled disaster not only for them, but for the entire army corps. With nothing to stop the northern Soviet breakthrough units, encirclement was a certainty.

Late on the 17th, the fate of the XIII Army Corps was finally sealed when the northern and southern Soviet armored pincers met about 30 miles west of L’vov on the bank of the Bug River. Hauffe ordered his army divisions to fall back, and elements of the 361st moved into a new line on the western flank of the Galizien. Other units were ordered toward the southwest, where it was hoped that a breakout attempt could be launched.

The following day, Model allowed the entire 4th Panzer Army, desperately fighting to the north of Hauffe, to begin a general withdrawal to the Bug River. Heeresgruppe Mitte had now been reduced to a shambles, making the 4th Panzer Army’s left flank untenable. The panzer army itself was in terrible shape. On the 18th it reported that it only had 20 serviceable tanks and 154 self-propelled guns.

With the 4th Panzer Army retreating, and seeing the success of his armored spearheads in the south, Konev saw the opportunity to annihilate Hauffe’s army corps. The German divisions were already being compressed into a pocket around Brody, so Konev issued orders for more infantry units to move to the area as quickly as possible to complete the encirclement and to finish the job of destroying the corps.

During the Battle of Brody, “The Air was Full of the Thunder of Tank Guns and the Noise of Engines.”

Hauffe was not about to wait for the infantry ring to close any tighter. The Soviet armored units had indeed linked up on the previous day, but there were still gaps in the enemy lines. Contacting General Hermann Balck, commander of the neighboring XLVIII Panzer Corps, Hauffe suggested that his corps attempt a breakout to the south. In conjunction with the attempt, he asked Balck to strike the Soviets, driving north to try and punch a hole in the outer Russian lines. The plan seemed militarily sound, but the distance that the XIII Army Corps had to travel to meet Balck was approximately 25 miles. In addition, the area that had to be traversed was a mixed terrain of swamp and heavy woods. Hauffe’s men would also have to cross the West Bug River before a linkup could be achieved.

During July 19, Hauffe worked to assemble his assault force. He picked Lasch’s 349th Infantry Division and Lange’s Korps Abteilung C to spearhead the breakout attempt. As those units were pulled out of the line, the already taxed forces of Hauffe’s other three divisions were ordered to fill in the gaps. This meant that Freitag’s division was responsible for most of the southeastern and eastern line of the pocket. Nedtwig’s 454th had the northern and northeastern sector, while Lindemann’s 361st, supported by corps units, defended the rest.

Although all sides of the pocket were attacked, the Soviet commanders chose to make their heaviest assaults against the Galizien Division. Red Army artillery pummeled the Ukrainian lines, while the Red Air Force blasted secondary positions. The death toll was heavy for the Ukrainians and morale began to sink, but the division continued to fight. Company and battalion commanders led counterattacks to seal breaches in the line, and most of the troops followed them to close the gaps.

A young Ukrainian officer, Lubomyr Drtynsky, described the frustration felt by the troops as they went against the Russians. “The air was full of the thunder of tank guns and the noise of engines. In Yaseniw the houses had begun to burn and more tanks were approaching. We could see the enemy forces consolidating. What could we do, attack the tanks with rifles? We needed planes and tanks. During this whole time I haven’t seen a single German plane or tank.”

The Russian attacks, coupled with difficulties assembling spearhead troops from the XLVIII Panzer Corps, forced the breakout attempt to be postponed until July 21. On July 20, the day that a group of German officers attempted to assassinate Hitler, the Soviets increased their heavy attacks against the Galizien.

Especially hard hit was Waffen Grenadier Regiment 31, which had already lost its commander as well as a large portion of its officers. Before the regiment could totally fall apart, its remnants were dispersed to other units in the division in hopes that fighting morale would return to its battered survivors. While the integration of forces was taking place, other Ukrainian units were pushed out of the village of Opaky, a strong defensive position in the line.

In the early hours of July 21, the approximately 30,000 men left in Hauffe’s command began the breakout attempt. Since there were few roads in the area, the breakout forces had to literally line vehicles bumper to bumper in order to negotiate the inhospitable terrain. Things went wrong almost from the start as the Red Air Force appeared at daybreak in waves.

As Russian fighters, bombers, and ground attack aircraft flew unopposed, some at treetop level, columns of smoke and fire erupted among the assembled vehicles. Large sections of the columns waiting to escape were soon nothing more than twisted masses of men and steel. Everywhere, the wounded screamed for help as flames consumed them. Those lucky enough to escape their vehicles soon found themselves being hunted down by strafing Soviet aircraft. A captured German officer later told Soviet interrogators, “[T]he Red Air Force did us great harm…They bombed us unceasingly and wouldn’t even let us raise our heads. Even the morale of old officers who fought in the 1914-18 war was affected.”

Discipline in some of the forward units, especially Korps Abteilung C, began to crumble, but others began to work their way through the Russian lines. General Lindemann’s 361st Infantry Division suffered heavy casualties as it battered its way into Soviet positions to make a breach through which others could pass. The men of the 454th Sicherheit Division, called forward to help, showed a similar disregard for casualties as they pushed the Soviets out of their forward lines.

Now that the breakout attempt was in full swing, the rear-guard units began to disengage with the advancing Soviets on their heels. Unaware of what had happened to the motorized columns, the retreating Germans and Ukrainians soon found themselves facing hopelessly clogged roads full of debris and bodies.

Faced with this new crisis, the Galizien Division finally started to become hopelessly unraveled. Word was passed down on the evening of July 21 that it was now every man for himself as Freitag realized that any cohesion in his command was now gone. The Galizien was now little more than a mass of desperate souls looking for a way to escape.

To their credit, some units within the Galizien, more or less intact, continued to fight the Russians effectively. Other individuals and units joined with German formations to continue the breakout effort, but many others could do little more than try to disappear into the inhospitable terrain. Leaderless and running short of ammunition, they fell easy prey to the advancing Russians.

On July 22, General Hauffe was killed. Later that day, General Lindemann was captured by the Russians, but his division continued to fight on. Throughout that fateful day, the XIII Army Corps struggled to make its way to freedom. Embedded in a group of about 800 men from the Galizien and the 361st Infantry Division, Freitag and most of his staff managed to link up with attacking forces from the XLVIII Panzer Corps. Other small groups of the Galizien made it to a breach made by a Kampfgruppe of the 8th Panzer Division.

Fierce fighting took place on all sides of the pocket throughout the 22nd, but by late evening the Russians had sealed off escape routes with an impenetrable ring of men. For the men remaining inside the pocket, there was only surrender or death.

Of the more than 35,000 men forming the XIII Army Corps on July 13, approximately 20,000 were listed as killed or captured. The Galizien Division, which had about 11,000 men at the start of the battle, had an effective strength of about 3,000 by the time it had fought its way out. Soviet writers, such as M.I. Traktuyev, claim a somewhat astonishing 20,000 enemy killed and 17,000 captured—a remarkable figure considering the prebattle strength of the army corps.

The elimination of the XIII Army Corps allowed Konev to release those units fighting in that sector for his main push on L’vov. By the end of the month, the important communications hub was in Soviet hands, and the Germans were forced to continue retreating westward.

Survivors of the Galizien Division were used to form the nucleus of a new 14th SS Ukrainian Division, and the rebuilt unit continued to fight the Soviets in Slovakia and Croatia. In late April 1945, the division designation was changed to the 1st Ukrainian Division of the Ukrainian Army. Fleeing to the West after the German capitulation, it surrendered to American and British forces on May 12. Most of the division was then moved to internment camps in Italy. With the onset of the Cold War, many of the Ukrainians were subsequently released and allowed to emigrate to the United States, Canada, Australia, and countries in Western Europe.

Pat McTaggart is an expert on World War II on the Eastern Front. He resides in Elkader, Iowa.

I though it a good read, I’ve much interest in the story as my grandfather died in the encirclement, he was with the 349th Paul Otto Hermann Geishirt, my mother met my father in Berlin Spandau around 1946. My father was with 2SAS transferred to ACC2 in 1945 British Army.

This last year I’ve spent a lot of time tracing him, my grandfather, as very little was ever said of my grandfather on the German side. He was report missing in this area Brody.

Thanks for your time and research