by Lt. Col. Harold E. Raugh, Jr., Ph.D., U.S. Army (Ret.)

To this day, the U.S. Marine Corps proudly commemorates in its service hymn the Marines’ first overseas operation on “the shores of Tripoli.” This was a military expedition characterized by piracy, boldness, intrigue, and adventure.

The Tripolitan War of 1801-1805, its background, and its results are chronicled in vivid detail by Richard Zacks in The Pirate Coast: Thomas Jefferson, The First Marines, and the Secret Mission of 1805 (Hyperion, New York, 2005, 432 pp., illustrations, endpaper maps, notes, bibliography, index, $25.95, Hardcover). Zacks reportedly specializes in “offbeat history” and is the author of The Pirate Hunter: The True Story of Captain Kidd.

The Tripolitan War of 1801-1805, its background, and its results are chronicled in vivid detail by Richard Zacks in The Pirate Coast: Thomas Jefferson, The First Marines, and the Secret Mission of 1805 (Hyperion, New York, 2005, 432 pp., illustrations, endpaper maps, notes, bibliography, index, $25.95, Hardcover). Zacks reportedly specializes in “offbeat history” and is the author of The Pirate Hunter: The True Story of Captain Kidd.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the four Barbary States of North Africa—Tripoli, Algiers, Tunis, and Morocco—controlled access to the Mediterranean Sea. The ruler of Tripoli demanded tribute from nations to navigate the Mediterranean, and the slave trade flourished. In 1801, this extortion rate was increased, and the fledgling United States refused to pay. Tripoli declared war on the United States.

American President Thomas Jefferson reacted by sending a punitive expedition to the Barbary Coast. A small U.S. naval force thereafter ineffectually blockaded Tripoli. In October 1803, the 36-gun frigate USS Philadelphia, commanded by Captain William Bainbridge and with a 307-man crew, ran aground and was captured. Navy Lieutenant Stephen Decatur led a force that boldly sailed a captured Tripolitan ship into the harbor and burned the Philadelphia in 1804.

To free the crew of the Philadelphia, the U.S. appointed William Eaton, the former consul in Tripoli, to foment civil war in Tripoli. Eaton was to lead a force to support Hamet Karamanli, the dispossessed but legitimate ruler of Tripoli. This was, according to Zacks, “the first time that the U.S. government ever sent an ‘agent’ or a ‘covert force’ to try to help overthrow a foreign government.”

Eaton, with eight Marines (led by Lieutenant Presley O’Bannon) and a mercenary force, started his operation from Alexandria, Egypt. The force crossed a bleak and scorching 520-mile stretch of desert and captured the fortress of Derna and held it against counterattacks for six weeks. This was a key factor, combined with the payment of a cash bounty that resulted in the release of the Philadelphia’s crew and a (temporarily) end to the hostilities.

This fascinating saga of piracy and slavery, political intrigue, foreign policy formulation, and a clash of personalities culminated in a bold and successful covert military operation. This is a well-written, colorful, and riveting account, serving also as a cautionary tale for those who want to try “to reshape the world through stealth.”

Recent and Recommended

Recent and Recommended

The Battle of An Loc, by James H. Willbanks, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 2005, 226 pp., illustrations, maps, figures, appendices, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

The Communist Easter Offensive of 1972 was the largest North Vietnamese assault since that of Tet 1968. Attacks took place from North Vietnam across the Demilitarized Zone, from Laos, and from Cambodia. Three North Vietnamese Army divisions, spearheaded by rumbling columns of fearsome T-54 tanks with massive artillery support, attacked Binh Long Province with Saigon as its objective. This was during the period of “Vietnamization” when American soldiers were being withdrawn from Vietnam and greater responsibilities given to South Vietnamese forces. South Vietnamese Army units, with American advisers, were rushed to reinforce the key city of An Loc.

Retired Army Lt. Col. James H. Willbanks was one of those American advisers at An Loc. Based his own experiences and subsequent in-depth research in American and South and North Vietnamese records, Willbanks has written an informative, highly readable, and compelling account of the 70-day Battle of An Loc. At this crucial conventional battle, South Vietnamese forces, supported by American airpower, blunted the North Vietnamese onslaught. This fierce engagement, of which little has been previously written, has been called “the single most important battle in the [Vietnam] war.”

In Brief

United States Army Unit and Organizational Histories: A Bibliography, by James T. Controvich, 2 vols., Scarecrow Press, Lanham, MD, 2003, 1,248 pp., $240.00, hardcover.

These two volumes, totaling 1,265 pages, are the product of a tremendous amount of detailed research and diligent study. Comprehensive and authoritative, United States Army Unit and Organizational Histories: A Bibliography lists thousands of Army unit and post histories. Volume I, focusing on the American Civil War, contains entries from the colonial era wars to military operations on the Mexican border in 1916. Federal and Confederate units, listed by armies, corps, divisions, and then functional area branches (ordered numerically in descending unit size, then alphabetically for named units), fill the first 25 chapters. The last chapter (26) lists titles relating to state militia and National Guard units. Volume II begins with American entry in World War I and includes entries published through 2002. Chapters are organized generally in the same way as in Volume I, with the addition of Chapters 33, “Commonwealth of the Philippines U.S. Army Units”; 34, “Installations (Camps and Forts)”; and 35, “State Militia, National Guard, and Military Histories.” James T. Controvich and Scarecrow Press are to be congratulated for, respectively, compiling and publishing this unmatched bibliography of U.S. Army unit and organizational histories. It will be an indispensable reference tool for military historians, genealogists, museum curators, librarians, and others.

Nero’s

Killing Machine: The True Story of Rome’s Remarkable Fourteenth Legion, by Stephen Dando-Collins, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 2005, 322 pp., maps, appendices, glossary, index, $24.95, hardcover.

This book is a re-created history of Legio XIV Geminia Martia Victrix—the Roman Army’s 14th Legion. The 14th Legion may have been formed by Julius Caesar in about 57 bc during the war in Gaul. Three years later, the 6,000-man 14th Legion was attacked in present-day Belgium and veritably wiped out to the last man; it had to struggle for decades to overcome the onus of this humiliating defeat. The 14th Legion was later stationed along the Rhine River and was one of four legions that participated in the invasion of Britain in 43 ad. The Legion distinguished itself in the fierce fighting against Welsh queen Boudicca in 60 ad, earning the title “Martia Victrix” (“victorious, blessed by Mars”). Author Stephen Dando-Collins sheds light on the campaigns and everyday life of Roman legionnaires and identifies and assesses recruiting cycles and terms of enlistment on unit effectiveness. Roman Army enthusiasts will welcome the publication of this interesting volume.

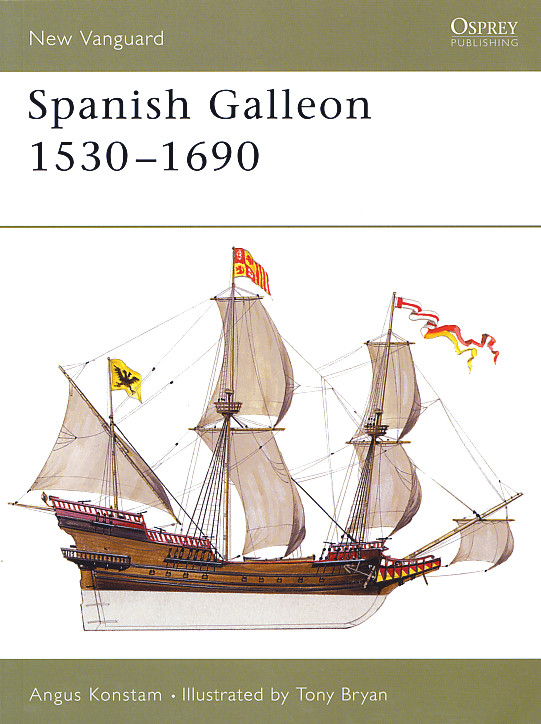

Spanish Galleon, 1530-1690, by Angus Konstam, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, England, 2004, 48 pp., illustrations, bibliography, index, $14.95, softcover.

Spanish Galleon, 1530-1690, by Angus Konstam, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, England, 2004, 48 pp., illustrations, bibliography, index, $14.95, softcover.

The galleon was a new and versatile type of ship designed by Spain in the 16th century. It was, as described by Angus Konstam in interesting detail, “developed to fulfill a need; the protection and later the shipment of specie [coins, ingots, or bullion] from the Spanish New World to Seville.” The design and development of this sturdy and seaworthy ship, long associated with fierce pirates, bountiful treasure, moonlit skies over the sultry Caribbean, and the Spanish Armada, are chronicled in this excellent introductory book. Related topics include shipbuilding and the armament and operations of the galleons. Especially interesting is the section, derived from firsthand and other accounts, describing life on board these ships. Galleons became the main warships of the Spanish fleet, and the Spanish employment of shipborne infantry, naval artillery, and the tactics employed by the Spanish Armada in 1588, are worthwhile to read. In common with other Osprey studies, Spanish Galleon is impressively illustrated with contemporary prints and paintings, color drawings, and finely detailed cutaway artwork.

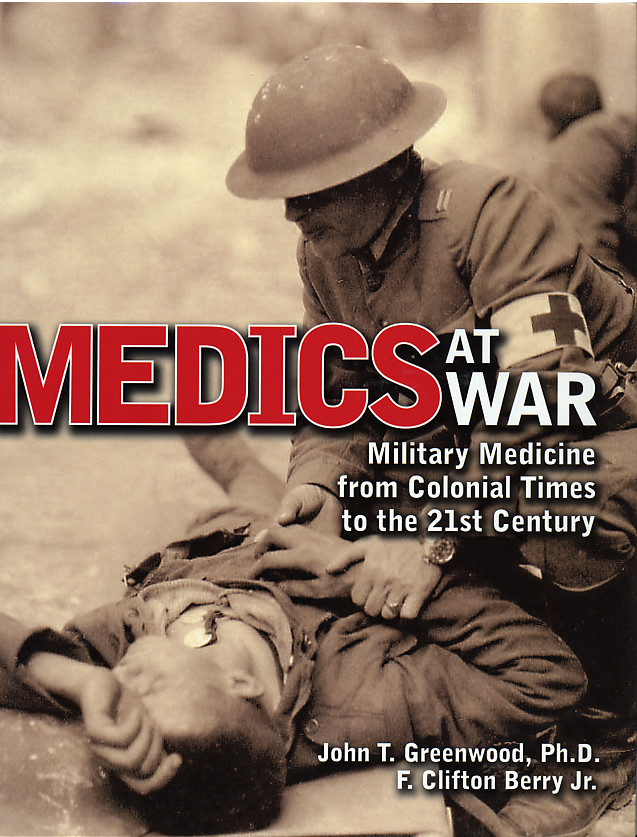

Medics at War: Military Medicine from Colonial Times to the 21st Century, by John T. Greenwood and F. Clifton Berry, Jr., Association of the United States Army and the Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2005, illustrations, bibliography, index, $34.95, large format hardcover.

Medics at War: Military Medicine from Colonial Times to the 21st Century, by John T. Greenwood and F. Clifton Berry, Jr., Association of the United States Army and the Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2005, illustrations, bibliography, index, $34.95, large format hardcover.

The progress of military medicine over the centuries, “from litter bearers and horse-drawn ambulances, to medevac helicopters and aeromedical evacuation aircraft,” has played an increasingly crucial role in the success of the U.S. armed forces. This profusely illustrated book chronicles in illustrations and words, through America’s conflicts and in 11 chapters, the evolving use of military medicine and the role of military medics (defined as “the men and women in the medical departments of the U.S. armed forces”). Beginning with the Battle of Breed’s (Bunker) Hill on June 17, 1775, during the American Revolution, U.S. medics have been unwavering in their commitment and courage to caring for soldiers suffering from enemy action or disease. This is a popular and easy to read, yet detailed and interesting, study. It contains combat information as well as peacetime military medical doctrine, transformation, and support. The photographs themselves are worth the price of this fine book. Past and present military medical personnel especially will find this book of value and interest.

Venereal Disease and the Lewis and Clark Expedition, by Thomas P. Lowry, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 2005, 117 pp., illustrations, map, tables, notes, index,

Venereal Disease and the Lewis and Clark Expedition, by Thomas P. Lowry, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 2005, 117 pp., illustrations, map, tables, notes, index,

$21.95, hardcover.

A generally neglected and unwritten aspect of Captain William Clark and Captain Meriwether Lewis’s 1804-1806 Corps of Discovery military expedition was the presence and fear of venereal disease. The concern was especially significant as the expedition did not have a physician. Lewis and Clark were surprisingly farsighted and realized that sexual contact between their soldiers and the Indians they encountered and the occurrence of venereal disease were inevitable. Thomas P. Lowry has mined the expedition’s journals and other records to show how prevalent these concerns were, the state of knowledge of venereal disease at the time, related medical supplies carried by the expedition, and “the actual events pertaining to sexual behavior during the journey.” There was a surprising amount of Indian hospitality in sharing their women with the explorers, using them as bartering tools and as rewards for providing medical care. Although the evidence is fragmentary, Lowry suggests that Lewis may have committed suicide in 1809 due to, among other factors, “the mental effects of encroaching syphilis.” In this intriguing and fascinating monograph, Lowry demonstrates that venereal disease was a major threat to the Lewis and Clark Expedition, “one that was in many ways as dangerous as grizzly bears, snakes, warfare, and slippery trails.”

Moscow, 1812: Napoleon’s Fatal March, by Adam Zamoyski, HarperCollins, New York, 2004, 672 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, sources, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Napoleon’s ill-fated invasion of Russia in 1812 is widely recognized as a pivotal event in European and world history. It marked the beginning of the end of Napoleon’s empire and the advent of Russia on the international stage. While nationalistic and political biases have tainted many earlier accounts of Napoleon’s Russian incursion, historian Adam Zamoyski has mined numerous foreign language sources, especially firsthand participant accounts, in writing this relatively balanced study. Napoleon gathered an army group of about 450,000 soldiers in Poland and crossed the Nieman River into Russia in June 1812. The Russians retreated eastward, drawing the French into the vast Russian interior. Illness prevented Napoleon from achieving victory at Borodino on September 7, 1812, although the French Army entered Moscow the next week. Disrupted supply lines, blinding snow, bitter cold, and fierce Russian counterattacks shattered the French, who began to retreat in disarray in mid-October 1812. The French fought a desperate rear-guard action, and by early December only about 10,000 effective French soldiers remained. Zamoyski’s harrowing account of Napoleon’s Russian debacle helps peel away layers of accumulated myths in search of the historical truth.

The Thin Red Line: An Eyewitness History of the Crimean War, by Julian Spilsbury, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 2005,340 pp., illustrations, maps, appendix, select bibliography, index, $32.95, hardcover.

The Thin Red Line: An Eyewitness History of the Crimean War, by Julian Spilsbury, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 2005,340 pp., illustrations, maps, appendix, select bibliography, index, $32.95, hardcover.

The Crimean War (1854-1856) was Great Britain’s only conflict in Europe during the century-long Pax Britannica that took place before World War I. British soldiers, allied with the French, Turks, and (later) the Sardinians, fought pitched battles with the Russians at Alma, Balaklava, and Inkerman. The British were totally unprepared for the harsh winter of 1854-1855 and suffered tremendous privations and semistarvation. The siege of Russian forces in Sevastopol began in the fall of 1854 and continued for many months until the fortress was attacked by the Allies and abandoned by its defenders in September 1855. Author Julian Spilsbury has written a narrative of the Crimean War, accented by the inclusion of a number of (generally previously published) participant accounts. This fine book is one of a number published to coincide with the 150th anniversary of the Crimean War.

Faces of the Civil War: An Album of Union Soldiers and Their Stories, by Ronald S. Coddington, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2004, 251 pp., illustrations, notes, references, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Faces of the Civil War: An Album of Union Soldiers and Their Stories, by Ronald S. Coddington, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2004, 251 pp., illustrations, notes, references, index, $29.95, hardcover.

“For the few days in which the military are being enrolled,” recorded one correspondent shortly after the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, “ the photographic galleries are thriving: the wise soldier makes his will, and seeks the photograph as possibly the last token of affection for the dear ones at home.” These small cartes de visite photographs, about the size of a modern baseball card, frequently showed awkwardly posed and apprehensive neophyte soldiers. These images usually remained with the soldier’s family, who generally waited eagerly during the months of war for word of their son’s or husband’s fate or his reappearance in the doorway. Author Ronald S. Coddington has collected and compiled 77 cartes de visite, not of prominent military leaders, but of enlisted soldiers and junior officers, the “wealthy and poor, educated and unschooled, native-born and immigrant, urban and rural,” all volunteers. More importantly, he has researched and composed poignant, interesting biographical sketches for each. As a result, Coddington has truly “given us an original memoir of the impact of the Civil War on ordinary American young men and their families.”

Winston Churchill, Soldier: The Military Life of a Gentleman at War, by Douglas S. Russell, Brassey’s, London, 2005, 480 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, notes, select bibliography, index, $32.95, hardcover.

Winston Churchill, Soldier: The Military Life of a Gentleman at War, by Douglas S. Russell, Brassey’s, London, 2005, 480 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, notes, select bibliography, index, $32.95, hardcover.

Winston Churchill is probably best known as the pugnacious, cigar-chomping, “V-sign” waving British prime minister who led his nation to victory in World War II. Churchill’s early life, as examined in enthralling detail by Douglas S. Russell, was dominated by the British Army and by journalism. Born in 1874, Churchill was commissioned into the 4th Hussars in 1895. He was highly ambitious. His “plan was to round out his [military] training with direct experience of warfare and, simultaneously, to report to the world on what he saw.” In 1895, Churchill took advantage of family connections and traveled to Cuba, writing about the insurgency there for the Daily Graphic. Two years later, he took leave from his regiment and accompanied the Malakand Field Force to the North-West Frontier of India. During the reconquest of the Sudan, Churchill was attached to the 21st Lancers and participated in the famous cavalry charge at Omdurman. He wrote for the Daily Mail during the Second Boer War. Churchill’s fame and notoriety achieved as a soldier and war correspondent helped him win election to Parliament in 1900—and he later commanded a battalion on the Western Front in 1916. This delightful book is interesting and entertaining, and this reviewer enjoyed reading it as much as the author seemingly enjoyed writing it.

Soldiers and Sled Dogs: A History of Military Dog Mushing, by Charles L. Dean, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 2005, illustrations, notes, index, $24.95, hardcover.

Author Charles L. Dean is a former U.S. Army officer who taught mountaineering and military skiing at the Northern Warfare Training Center in Alaska. After he left the Army, he became interested in dog teams and military mushing. Dean traces military dog team transportation to the early 1900s, when the U.S. Army began serving in Alaska, and World War I, when various European forces used dog teams on the Western Front and in the Alps. In the 1920s, the Army developed official doctrine for dog transportation. During World War II, the Army trained dog teams at Chinook Kennels, New Hampshire; Camp Rimini, Montana; Camp Hale, Colorado; and Fort Robinson, Nebraska. A primary use of sled dog teams was search and rescue operations for downed pilots in the Arctic. The German 6th Mountain Division used dog teams in Finland and in the Vosges Mountains of France during World War II. The U.S. Army stopped using sled dogs in 1954, although the Danes continue to use dog sledge patrols in Greenland. This fine book on a little known military topic, superbly illustrated with numerous photographs and sketches, is surprisingly interesting and a pleasure to read.

Five Days in October: The Lost Battalion of World War I, by Robert H. Ferrell, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2005, 130 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, notes, index, $19.95, hardcover.

Five Days in October: The Lost Battalion of World War I, by Robert H. Ferrell, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2005, 130 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, notes, index, $19.95, hardcover.

The saga of the so-called “Lost Battalion” of the 77th Division captured the public imagination during the closing days of World War I, and it continues to do so to this day. It occurred during the second phase of the Meuse-Argonne offensive, which kicked off on October 2, 1918. The 1st Battalion, 308th Infantry Regiment, of the 77th Division, commanded by Major Charles W. Whittlesey, attacked “without regard to the exposed conditions of the flanks” up a ravine to capture the Charlevaux Valley. The unit stopped for the night before reaching its objective. It then realized it was located in a “pocket” ahead of other friendly forces. Never lost, Whittlesey’s surrounded men refused to surrender and defied continuous German fire, attacks, and hunger for five days until relieved. Author Robert H. Ferrell dissects and assesses this episode in a thorough and balanced manner. In this slim monograph, Ferrell shows that, despite battlefield confusion and press exaggeration, “together with what happened at the Alamo and the Little Big Horn, the Lost Battalion stood for courage, defiance in the face of odds, [and] willingness to fight when others might have given up.”

Foch: Supreme Allied Commander in the Great War, by Michael S. Neiberg, Brassey’s, Washington, D.C., 2003, 125 pp., illustrations, maps, chronology, notes, bibliographic note, index, $19.95, hardcover.

Marshal of France Ferdinand Foch (1851-1929), according to Professor Michael S. Neiberg, was “the greatest French soldier of the twentieth century—a man who shaped the definition and conception of the modern general.” In this superb volume in Brassey’s Military Profiles series, Neiberg chronicles Foch’s military career and contributions. Chapter 1 covers Foch’s life and career from birth in 1851, service in the French Army during the Franco-Prussian War, and commissioning in 1872 through his assignment as commander of the Twentieth Corps on the eve of World War I in 1914. Foch’s World War I service, culminating as “generalissimo” of the Allied forces in May 1918, is narrated and assessed in Chapters 2 through 6. The last chapter of the book, “Losing the Peace,” highlights Foch’s view that despite the Versailles Treaty, Germany remained “a mortal enemy that would continue to pose a serious threat to France.” This nicely written and insightful condensed biography paints a vivid picture of Foch as a military commander, as well as of French military doctrine and the conduct of operations during the Great War.

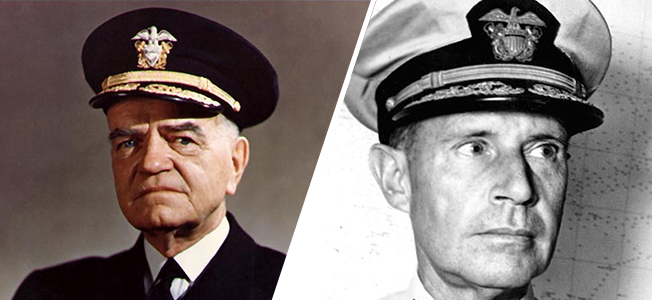

MacArthur’s Escape: John ‘Wild Man’ Bulkeley and the Rescue of an American Hero, by George W. Smith, Zenith Press, St. Paul, MN, 2005, 288 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, source notes, selected bibliography, index, $24.95, hardcover.

MacArthur’s Escape: John ‘Wild Man’ Bulkeley and the Rescue of an American Hero, by George W. Smith, Zenith Press, St. Paul, MN, 2005, 288 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, source notes, selected bibliography, index, $24.95, hardcover.

According to author and former journalist George W. Smith, this book is “the true story” of General Douglas MacArthur’s controversial evacuation from the beleaguered Philippines to Australia in March 1942. With an American surrender to the advancing Japanese appearing imminent, President Franklin D. Roosevelt reportedly ordered MacArthur to escape from Corregidor. On March 11, 1942, MacArthur, his family, and key staff members boarded four motor torpedo (PT) boats, commanded by Navy Lieutenant John D. Bulkeley, and departed the island fortress. Through enemy-patrolled, stormy, and perilous waters, the group arrived two days later at its rendezvous point on Mindanao, from which MacArthur and his party flew to Australia. For this daring exploit, both MacArthur and Bulkeley received morale-raising Medals of Honor. Bulkeley was also lionized in the book and motion picture entitled They Were Expendable. This episode, however, fills only a small portion of this book, which contains considerable extraneous material, long gratuitous quotes, speculation, and other poorly documented information. The role of PT boats in the early Pacific war is highlighted.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments