By Glenn Barnett

After the Great War, the leading naval powers met to try to avoid another ruinously expensive arms race and, hopefully, prevent future wars. Great Britain, the United States, France, Italy and Japan agreed to set limits on the number and sizes of warships that each nation could build.

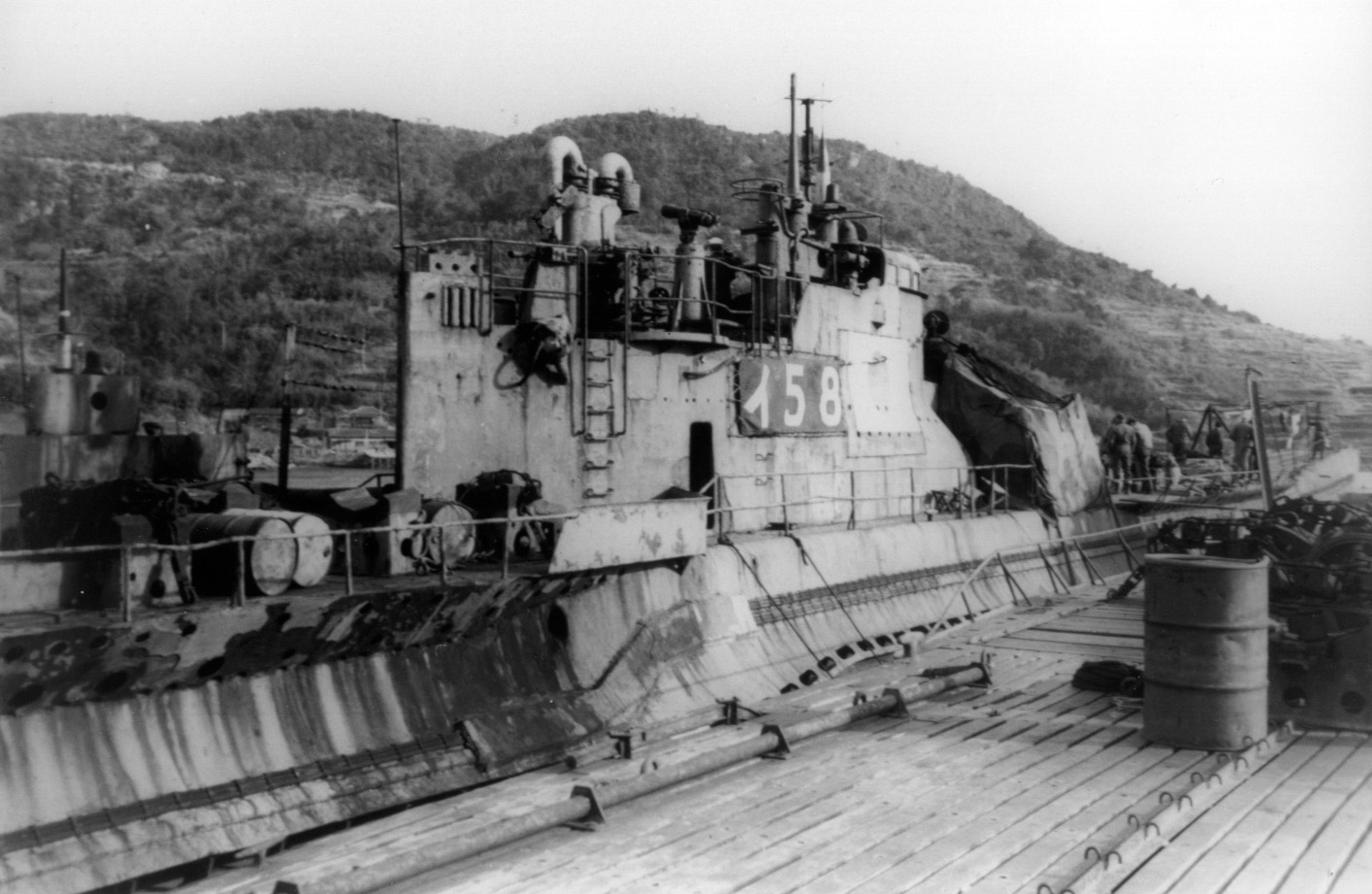

The limit was for submarines was 2,000 tons, a figure most nations found easy to comply with as World War II began. British, Italian and German submarines topped out at less than 1,000 tons. American attack submarines, which had to ply the wide Pacific, remained steady throughout the war at around 1,500 tons.

The Japanese knew they could not match the industrial might of the Allied nations and so built fewer, but larger and more powerful ships. The Bismarck weighed in at 41,000 long tons, while the Iowa-class of American battleships reached 45,000 tons. The Japanese built two battleships—Musashi and Yamato—that topped out at 64,000 tons. These two goliaths also boasted the biggest guns ever mounted on warships.

It was the same with submarines. The I-class boats, considered to be fleet submarines, had long range and good speed. The I-19 displaced 2,584 long tons and mounted a 5.5-inch naval gun as compared to the American Gato-class subs at 1,525 long tons with a 3-inch gun. As the war progressed, American subs would also mount 5-inch guns. I-19’s top speed was 23 knots, and she had a range of 14,000 nautical miles at her most economical speed of 16 knots on the surface, compared with the Gato submarines, which were designed for 11,000 miles at nine knots.

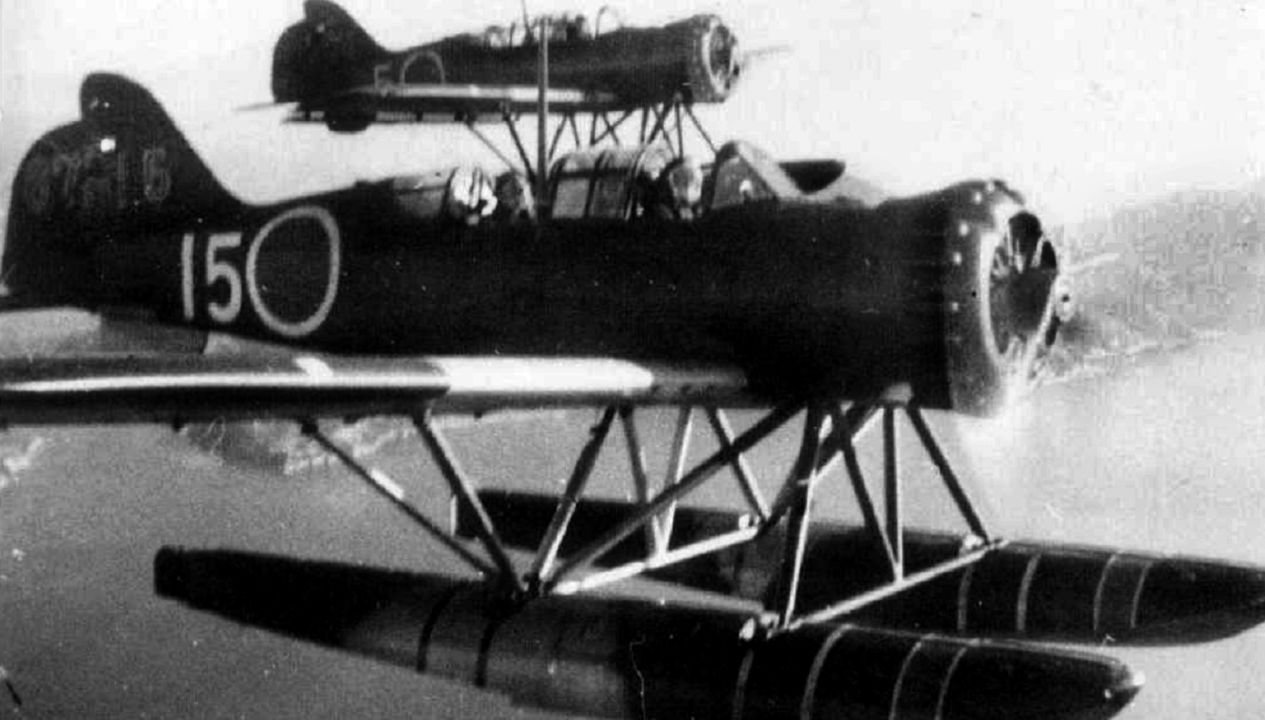

The I-19—and other submarines of the B-Type of the I-class—had another weapon that no other nation built into its submarines: They carried an airplane, which made them underwater aircraft carriers. Housed in an air-tight compartment, I-19 carried a Yokosuka E14Y float plane (allied designation “Glen”) that could be used for scouting, reconnaissance, or light bombing. The size and the air component of the I-boats required a larger crew, from 94 to 105 men compared to the Gatos complement of around 60 men.

Her most formidable weapon, however, was the Type 95 torpedo, a modified version of the ship-launched Type 93 “long lance” torpedo and the most advanced in the world throughout the war. It had a range three times that of its contemporary American counterpart, the problem-plagued Mark 14 torpedo. The Type 95 was also the fastest torpedo in the world and its warhead was larger than any other submarine torpedo.

Type 95 propulsion consisted of a kerosene-oxygen fuel with a wet-heater rather than the compressed air used by most other navies. Allied ship captains who thought themselves out of range of Japanese torpedoes had little time to correct their mistake.

I-19 was commissioned on April 1, 1941. Her first captain was Narahara Seigo. On November 21st, I-19 departed Japan for Hawaii, refueling en route. Her assignment, along with I-21 and I-23, was to scout in front of Admiral Chūichi Nagumo’s carrier force, which was rapidly approaching Pearl Harbor. On December 7, I-19 patrolled at a distance of 120 miles northeast of Oahu, on the lookout for any American ship that might come within range of the carrier task force. No such threat was encountered.

On December 14, I-19 was ordered to the West Coast of North America along with I-15, I-9, I-10, I-17, I-21, I-23, I-25, and I-26. Each boat was assigned a specific area along the west coasts of the U.S. and Canada. They were to attack shipping until Christmas Day. Then, simultaneously, they were all to shell their portion of the coast to create panic in the western United States and Canada before returning home.

When I-19 arrived on station off the California coast, north of Santa Barbara, her lookouts spotted the 4,200-ton Norwegian freighter Panama Express. The submarine fired a torpedo at her but missed. The next day, lookouts found the 10,763-ton Standard Oil Company tanker SS H.M. Storey and gave chase for an hour. Three torpedoes were fired at Storey, but they all missed. Storey’s SOS brought naval patrol planes, forcing I-19 to dive to escape depth charges.

On Christmas Eve, near San Pedro, another torpedo was launched toward the 2,146-ton lumber schooner Barbara Olson. It, too, missed. Later the same day, I-19 attacked the 5,695-ton lumber carrier Absaroka. One of two torpedoes hit the ship and caused damage but did not sink Absaroka because of her buoyant cargo of lumber. Again, the I-19 was subjected to a depth charge attack before escaping.

The synchronized Christmas Day shelling of the coast was postponed until the 27th, but by then the Japanese boats along the west coast reported that their fuel reserves were rapidly being depleted. They were all recalled without the planned shelling.

For most of the boats assigned to harass the coast of North America, it was a disappointing trip. They had come a long way, expended precious torpedoes, placed wear and tear on men and machines, accomplished little, and endured depth-charge attacks from thoroughly alarmed and vigilant American defenses.

Life aboard a submarine of any nation was not pleasant. Japanese submarine designers paid little attention to creature comforts. Fresh water was in short supply; fresh food was exhausted quickly. There was little or no personal space. Even with the greater size of the I-class subs, wiggle room was precious. Heat, too, was a problem; after diesel engines ran for several hours on the surface at night, the boat would submerge to run on batteries, but the built-up engine heat permeated the entire claustrophobic interior of the tube. It was also constantly clammy inside, which encouraged the growth of mold.

In Tokyo, an operation called “K-1” was devised to raid Pearl Harbor again. This time, rather than risk an entire carrier force on an alert enemy, two Kawanishi H8K “Emily” flying boats would be used. The planes, each carrying 1,800 pounds of bombs, departed Wotje Atoll in the Marshall Islands group and flew to French Frigate Shoal in the Hawaiian Island chain to refuel from I-class submarines acting as tankers.

For its part in the raid I-19, I-15, and I-26 had their float planes removed from their on-board hangers and replaced with six tanks filled with aviation fuel. Their job consisted of refueling the two Emilys in the calm water of the shoals for the attack on Pearl Harbor. I-19 was also used as a radio beacon to guide the Emilys to their refueling spot.

On the night of March 4, 1942, I-19 and her sisters refueled the Emilys as planned. The seaplanes flew on to Pearl Harbor and an ineffectual raid because of bad weather. The Americans did not even realize that they had been bombed. I-19 then returned to Yokosuka at the entrance to Tokyo Bay for a much-needed overhaul. She was still there when the Doolittle Raid attacked Tokyo on April 18.

In May, I-19 took part in the complicated strategic plan to attack Midway Island. For her part in the scheme, she was assigned to the Aleutian Islands to support the diversionary invasion of Attu and Kiska Islands. On May 26th she was scouting for any unknown American activity on Umnak Island. Her float plane was being assembled when an American destroyer was spotted. Captain Narahara recalled the deck crew and crash dived, which destroyed the half-assembled float plane. Continuing with their scouting mission, the crew of I-19 made a two-day submerged, periscope observation of Dutch Harbor.

On July 7, she arrived safely back at Yokosuka and was dry docked for repairs. While there she received a new captain, an experienced submarine commander, Kinashi Takakazu. I-19 was still in dry dock when, on August 7th, the U.S. Marines landed on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands. When repairs were finished, I-19 was dispatched to meet the American challenge.

By August 24th, I-19 arrived on station 200 miles southeast of Guadalcanal and took up patrol duties, searching for targets. She was still there on September 15. Meanwhile, two separate American task forces, centered on the aircraft carriers Wasp and Hornet, steamed side by side. This impressive armada escorted a reinforcement convoy of six troop transports carrying the 7th Marine Regiment from Espiritu Santo to Guadalcanal. The carriers were steaming in sight of each other about 8 miles apart.

While cruising submerged, the sound operator on I-19 picked up the noise of several ships on a northerly course. At 10:50 a.m., Captain Kinashi looked through his periscope to see the American squadron heading in his direction. Although they were zig-zagging, one of their turns put the carriers into the wind for the launch and retrieval of planes. Wasp headed right for I-19. Kinashi calculated the carrier’s course and speed, and at 11:45 he used all of his forward tubes to fire a spread of six torpedoes at Wasp.

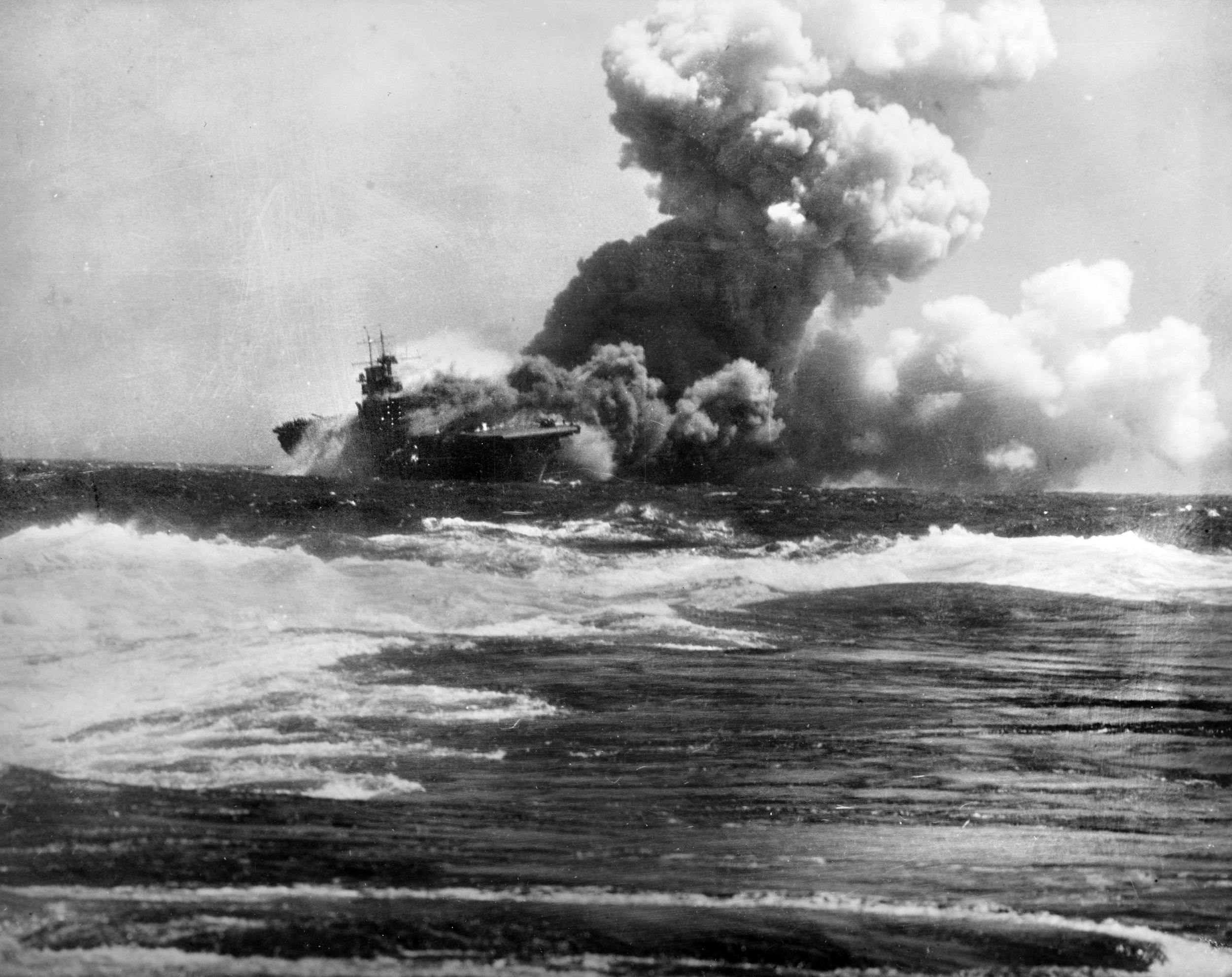

At that same moment, aboard Wasp, ship’s cameraman Leslie Elliott Jr. was standing watch on the bridge, observing the retrieval of planes, when torpedoes were spotted in the water heading for them. The helmsman desperately turned his wheel hard to starboard, but the bow had only just begun to answer her helm when three of the torpedoes slammed into the carrier causing multiple explosions that, among other things, ruptured the ship’s water main and pumps, which prevented her crew from fighting the resulting fires.

Elliot was hit by shrapnel in the forehead and bled profusely. His first impulse was to set up his camera and record the action, but Captain Forrest P. Sherman told him to get to sickbay as fires raged uncontrolled in the doomed ship. While standing in the hangar deck, Elliot heard the order to abandon ship as thick black smoke filled the air and secondary explosions rocked the ship. Elliot climbed over the side on a net ladder and dropped into the sea to await rescue. When it was all over, Wasp lost 193 killed and 367 wounded.

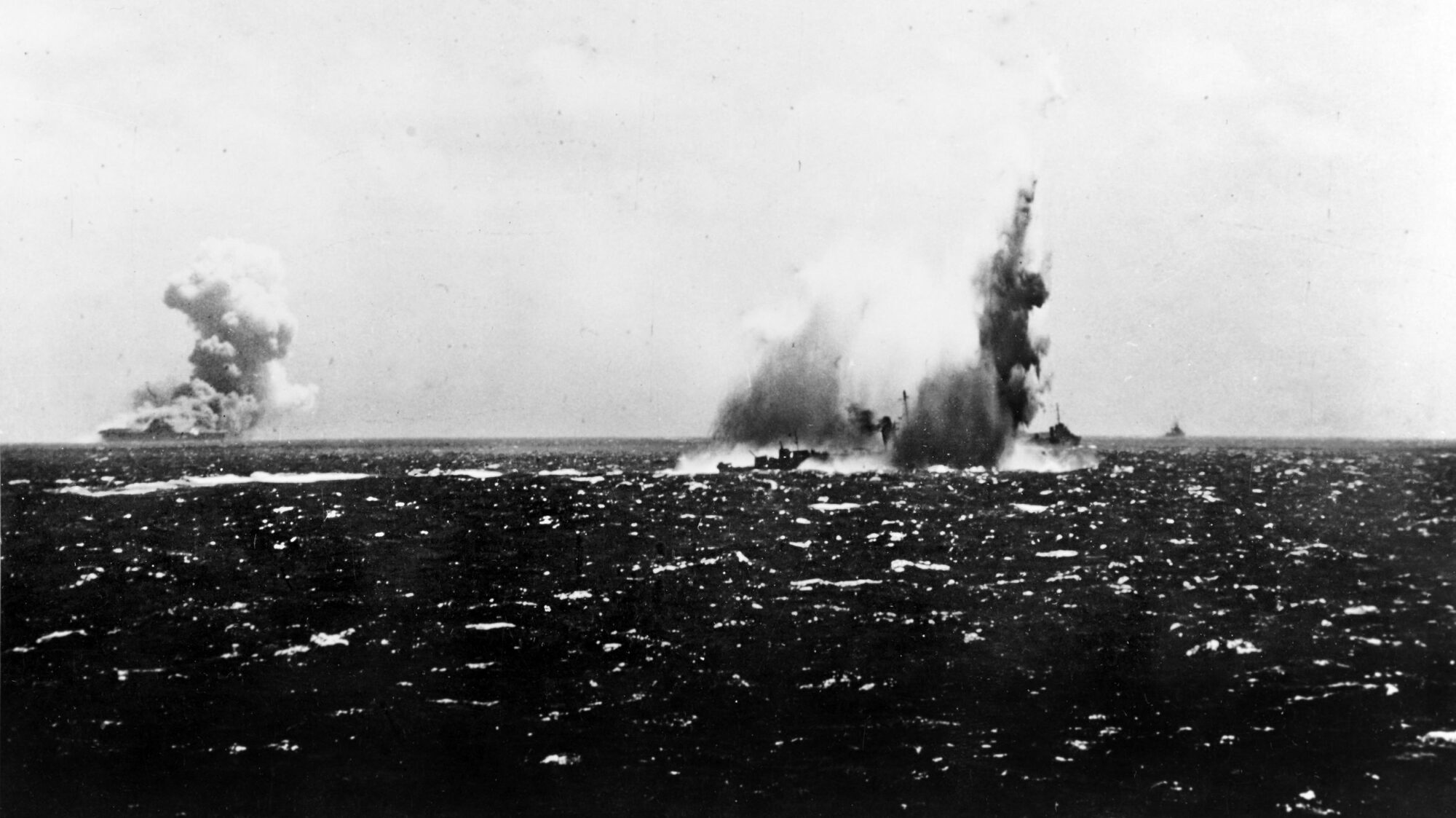

While Wasp convulsed, the destroyer O’Brien’s lookouts spotted a torpedo in the water and were able to speed up as it passed astern. The crew did not see the torpedo that then hit the ship on the port bow. It tore open a deep gash and destabilized the keel. O’Brien was still afloat and could steam under her own power, but the explosion had caused structural damage. O’Brien steamed to Espiritu Santo for temporary repairs. She was seeking more lasting repairs on Pago Pago when her seams opened up on October 19th and she finally sank, a month later, from I-19’s torpedo blast.

The spread of torpedoes from I-19 was not done yet. Another one slammed into the battleship North Carolina on her port bow, just forward of the thick armor belt designed to protect her from torpedoes. The enormous blast shook the ship, jolting it to starboard. Tons of fuel oil and water shot skyward. Seawater quickly flooded into the 32-by-18-foot hole, causing the mighty battleship to list to port, a situation quickly corrected by counter-flooding compartments on the starboard side.

Ruptured fuel-oil tanks exploded, causing fires that threatened to destroy the ship if they reached the forward magazines. The magazines were quickly flooded to prevent this, and the ship’s two forward turrets were put out of action. The flooding saved the ship, but in her condition, she could not fight. The radar was also knocked off line, as were the catapults. Five men were killed and 23 were wounded. The accumulated damage caused by that single torpedo strike was arguably the most impressive single attack by any submarine in history.

Now it was I-19’s turn to be the target. Angry and humiliated destroyer captains, who had failed to protect their carrier, converged on the offending submarine. Captain Kinashi maneuvered his boat to the wake of the dying Wasp and submerged to 265 feet. The detritus falling overboard from the carrier, airplanes, bombs, tools and much more confused the destroyers’ sonar. The first depth charge exploded just six minutes after the last torpedo hit North Carolina. Soon, the depth charges were exploding all around. They rained down as many as 80 depth charges. Yet I-19 survived to fight another day.

After some R&R and replenishment of stores and weapons at Truk (now called Chuuk) Lagoon, I-19 was assigned to reconnoiter the town of Noumea on New Caledonia. On October 19th, she launched her Glen floatplane to observe from overhead but could not recover it intact. The submarine would stay on patrol near Noumea until November 12th, when she was reassigned to participate in the “Tokyo Express” to deliver supplies and reinforcements to Guadalcanal. Her first run was disrupted by an attack from American aircraft, and she dove before completing her task.

The Japanese then developed a new resupply tactic. The submarines carried supplies wrapped in floating rubber containers that were released, at night, while submerged to avoid the vigilant American air patrols. In all, I-19 would make three successful supply runs to Guadalcanal, delivering a total of 52 tons of badly needed supplies.

On January 25th, 1943, she arrived back in Japan for a quick overhaul. After a rapid turnaround, I-19 returned to Guadalcanal to be a part of Operation “KE,” the evacuation of Guadalcanal. She did her share in extracting 11,700 exhausted and starving troops from the island.

By April, she had begun a patrol around the New Hebrides and Fiji Islands. On April 30, 1943, she torpedoed and sank the 7,176-ton Liberty ship Phoebe A. Hearst. On May 2nd, the 7,181-ton American freighter William Williams was severely damaged by one of her torpedoes. Finally, on May 16th she torpedoed and sank the 7,181-ton freighter William K. Vanderbilt. After her successful patrol, I-19 replenished at Truk and began a new patrol off Fiji. This time, she torpedoed the 7,176-ton Liberty ship M. H. DeYoung. After I-19 departed, DeYoung, still afloat, was towed into the nearest allied port but was beyond repair.

Returning to Truk, I-19 received her third commander, Kobayashi Shigeo, before setting out on her next patrol. In November she quietly approached Oahu and launched her float plane after sundown. The Glen made a reconnaissance pass over Pearl Harbor and returned to the submarine in the dark. The pilot reported seeing one battleship and one carrier in the harbor, and the news was radioed back to Truk. Unfortunately, as pilot and plane were being recovered, American planes were spotted, forcing I-19 to crash dive without recovering the float plane.

On November 19, 1943, the captain made his regular situation report to Tokyo. It would be his last. The next day, American troops landed on Tarawa and Makin Islands. On the 25th near Makin Island, the destroyer USS Radford (DD-446) made night-radar contact with a surface vessel 8 miles distant and changed course to intercept. When radar contact was lost, the destroyer switched on its sonar and reacquired the submarine. Radford went to general quarters and approached quickly to release a pattern of seven depth charges. I-19 was sunk with all 105 of her crew.

Japanese submarines and their crews did all that skill, luck, and courage could accomplish, but it was not enough. The boats were technologically superior at the beginning of the war but, for the I-class, their large size made them vulnerable as the new technologies of radar, sonar, and improved depth charges and tactics came on line. I-19 was caught up in the carnage that befell her country.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments