By Jeremy Green

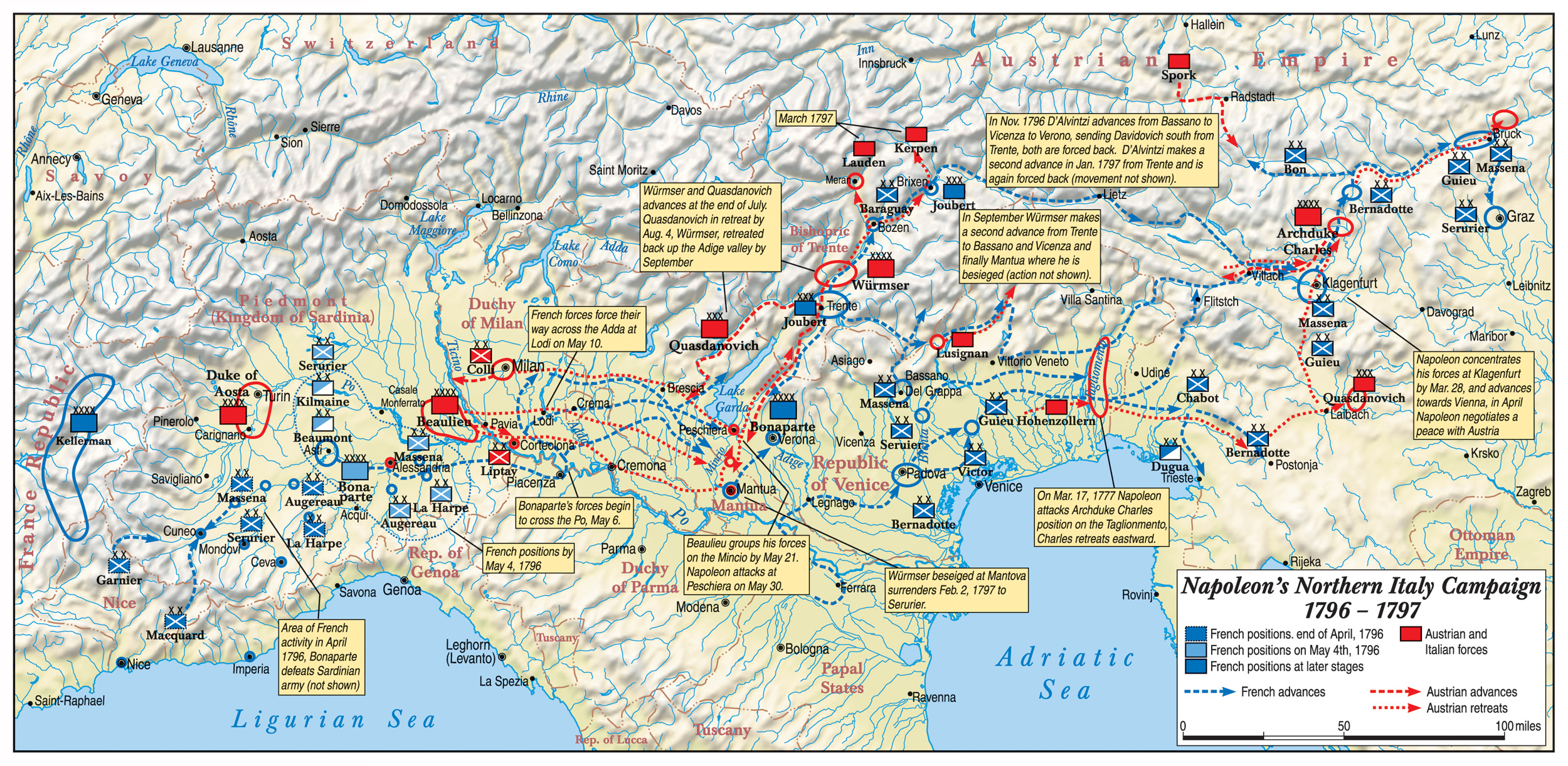

The newly appointed 26-year-old commander-in-chief of the French Army of Italy arrived at Nice headquarters on March 27, 1796. Scar-lipped Sérurier, adventurous Augereau, and calculating Masséna, with his legendary passion for wealth and beautiful women, were all smirking as they prepared to meet this political soldier. How could they respect a man who achieved this highest rank not by heroism in war, but by firing his cannon at the Parisian mob to save the French government, and by marrying the discarded mistress of the influential director of the French government, Paul Barras? The youthful general, who according to one contemporary looked more like a mathematician than a military commander, eagerly showed the portrait of his beautiful new wife, Josephine Beauharnais, to the cynically amused older soldiers.

But this all changed in a moment. According to Count Yorck Von Wärtenburg: “Owing to his thinness, his features were almost ugly in their sharpness; his walk was unsteady, his clothes neglected, his appearance produced on the whole an unfavorable impression and was in no way imposing; but in spite of his apparent bodily weakness he was tough and sinewy, and from under his deep forehead there flashed despite his sallow face, the eyes of genius, deep seated, large and of a grayish-blue color, and before their glance and the words of authority that issued from his thin, pale lips, all bowed low.”

Big, gruff Augereau, who had decided to insult the frail young commander, confided to Masséna that this “little bastard of a general” had frightened him. In fact, very soon all three division generals were impressed by their commander’s energy and commitment to their future success. “A moment afterward,” recounted Masséna, “he put on his general’s hat and seemed to have grown two feet. He questioned us on the position of our divisions, on the spirit and effective forces of each corps, prescribed the course we were to follow, announced that he would hold an inspection on the morrow and on the following day attack the enemy.”

Napoleon Promises Food and Riches to the Ragged French Army of Italy

Thus Napoleon Bonaparte launched his first campaign. His military genius and administrative accomplishments would astonish the world.

The Army of Italy that General Bonaparte inherited was a ragged and disgruntled lot of soldiers short on pay, rations, and supplies. Upon his arrival at Nice, young Bonaparte was greeted by a mutiny of the 209th Demibrigade, which refused to move forward, claiming it had no money or shoes. The general grasped the situation immediately as he addressed his dispirited men: “Soldiers! You are hungry and naked; the Government owes you much but can give you nothing. The patience and courage which you have displayed among these rocks are admirable; but they bring you no glory—not a glimmer falls upon you. I will lead you into the most fertile plains on Earth. Rich provinces, opulent towns, all shall be at your disposal. There you will find honor, glory and riches. Soldiers of Italy! Will you be lacking in courage or endurance?”

The effect of this speech was positive. The general won over the confidence of many with his promise of food and riches; those of more noble character he won over by promises of honor and glory.

Still, the problems facing the French general were great. The 37,000-strong French Army of Italy faced a combined force of 52,000 Austrian and Piedmontese troops. But the scattered location of these enemy troops that were separated by mountains and their mutual distrust of one another offered the enterprising French commander the opportunity of a successful campaign.

Napoleon’s Trusted Commanders

The three division commanders who presented themselves to General Bonaparte were formidable men. At 53, the tall and gloomy Jean Sérurier was the eldest. A former nobleman, his 34 years in the old Royal Army had made him a soldier of the “Ancien Régime.” In sharp contrast was the 38-year-old Charles-Pierre-François Augereau, whose towering height and reputation as one of France’s most accomplished swordsmen had made him an imposing figure. Despite his humble origins in the Paris gutters, Augereau’s coarse language, incredible adventures, and popularity with his men, as well as his ability as a tactician, rendered him a thorough soldier.

Finally, André Masséna, who had previously served with Bonaparte at Toulon in 1794, was already famous as the victor of the Battle of Loano. Although Masséna would demonstrate his infinite thirst for riches and women, he would also prove to be one of Napoleon’s most capable generals.

In addition to these three, Napoleon would be served by several men he had brought with him from Paris. These included Alexandre Berthier, who would become perhaps the best chief of staff in military history; Colonel Joachim Murat, arguably the most flamboyant cavalry general who ever fought; the young artillery expert Auguste Marmont; the impetuous Jean-Andoche Junot; and the faithful Géraud-Christophe-Michel Duroc.

Meanwhile, already serving the Army of Italy in subordinate positions were future great French generals: the fearless Jean Lannes, the cool Jean-Baptiste Béssières, the able Louis-Gabriel Suchet, plus Barthélemy-Catherine Joubert and Claude Victor.

The Austrians Strike First

Opposing Bonaparte was the newly arrived Austrian commander, 72-year-old General Johann Beaulieu, with some 19,500 soldiers dispersed farther north at Alessandria. There were two other armies immediately facing the French. General Eugène Argenteau led 11,500 Austrians in the town of Aqui and along a line of outposts from Carcare to Genoa. General Leonardo Colli strung out 20,000 Piedmont troops along a line from Ceva to Cosseira, where they were strengthened by an Austrian detachment under the command of Johann Provera. These numerically superior opponents would indeed be formidable if they were united against the ill-equipped and outnumbered French Army of Italy. However, moving from a position of defense, Napoleon began immediately to assemble his army for seizing the offensive.

Bonaparte’s primary objective was to destroy General Colli and drive Piedmont out of the war. Careful study of the maps with Berthier indicated that the town of Carcare, the central position, was the vulnerable link joining the troops of Piedmont and Austria. By concentrating his forces at this point of attack, Bonaparte would attain numerical superiority over each of his isolated adversaries. Thus Masséna and Augereau were ordered to move on to Carcare. To achieve this successful concentration for attack, a diversion by Sérurier around Ormea would occupy Colli’s attention. At the same time, 6,800 men of Generals Macquart and Garnier would demonstrate before Cuneo. General Amédée La Harpe’s division would move toward Sassello, linking up with French Brig. Gen. Jean-Baptiste Cervoni, who would continue his activity in Voltri.

All of these operations were to go into effect on April 15, but General Bonaparte was forced to begin the campaign four days earlier than planned. On April 10, the Austrians unexpectedly attacked Cervoni’s isolated brigade at Voltri. Ironically, Beaulieu’s attack actually helped Napoleon. By uncovering his true position, the Austrian commander-in-chief revealed himself as being too distant to offer any aid to his men once Bonaparte attacked either Colli or Argenteau.

Nevertheless, Bonaparte was taken by surprise. Cervoni, with great obstinacy, managed a masterful retreat before Beaulieu’s superior Austrian forces. At the same time, French Colonel Antoine Rampon held off attacks by Argenteau’s Austrians. The Austrian offensive had begun, but was soon curtailed.

Napoleon’s First Victory: the Battle of Montenotte

The French were once again in a position to seize the initiative. Ignoring Beaulieu, who was too far off to reinforce his subordinates, Bonaparte moved immediately. During the morning of April 12, 9,000 Frenchmen displaying great élan charged Argenteau’s 6,000 surprised Austrians at Montenotte. While the 7,000 French under La Harpe began a frontal attack on the Austrian position, General Masséna at the head of Menard’s brigade caught the Austrians unaware by attacking their right flank. Argenteau realized he could not withstand the two-pronged onslaught and ordered a retreat. The battle became an Austrian rout—Argenteau had only 700 men left under his direct command upon his arrival at Dego.

The Battle of Montenotte, Napoleon’s first victory, was complete. As soon as he had driven the Austrian Army from the field the captured Austrian muskets were distributed among the thousands of French soldiers under General Augereau’s command. These soldiers had advanced upon the enemy armed only with courage—they had possessed no firearms. The “horde tactics” of the French revolutionary armies were indeed a formidable weapon, and in the hand of Bonaparte they would prove irresistible.

In Napoleon’s first victory, Argenteau lost nearly 2,500 men—hundreds killed, many wounded, and some missing. Having learned of the defeat of his subordinate Argenteau at Montenotte, and having found Voltri abandoned by Cervoni, Beaulieu now renounced his initial objective and attempted to reach Dego instead. His new goal was to join his troops with the remainder of Argenteau’s soldiers, as well as with Colli’s surviving Piedmontese forces. Bonaparte had correctly deduced from his maps that Beaulieu would not cross the mountains, nor would he be a factor in the next few hours of action.

The French commander had crushed Argenteau by concentrating superior weight at the point of contact. Now that one foe had been neutralized, the young French leader would reach for his main objective, Colli’s Army of Piedmont.

Augreau Attacks at Millesimo

Assembling 10,000 men consisting of Augereau’s entire division and a portion of Masséna’s, Bonaparte directed them via Millesimo toward Montezemolo on the road to Ceva. Sérurier was ordered to envelop Colli’s right. The French would now have 25,000 soldiers against Colli’s 20,000. Meanwhile, Generals La Harpe and Masséna, with the remainder of Masséna’s division, marched across the hills to Dego to prevent Argenteau and his regrouping Austrians from interfering with the main French thrust on Colli’s Piedmontese army. Colli had moved his right toward Millesimo. He should, however, have gone farther toward joining with Argenteau’s Austrians in Dego. To guard against unforeseen problems, Bonaparte ordered a central reserve of six battalions and all of Henry Stengel’s cavalry to remain at Carcare.

On the morning of April 13, Augereau struck the left wing of the Piedmontese forces at Millesimo. All had been going favorably as the French advanced upon Ceva until Augereau came upon the ruins of Cosseria Castle where a small garrison of 900 grenadiers under Austrian General Giovanni Provera was defying French attempts to dislodge them.

“Nothing more terrible,” wrote Colonel Joubert, “could be imagined than the assault, where I was wounded in passing through a loophole; my carabiniers held me up in the air, with one hand I grasped the top of the wall. I parried stones with my saber, and my whole body was the target for two entrenchments dominating the position ten paces off.”

Although Augereau had won the Battle of Millesimo, Provera’s continued resistance at Cosseria was causing Masséna on the other French flank to delay his attack, which Bonaparte had instructed could begin only after Cosseria had fallen. A valuable 24 hours was lost. The next morning, April 14, the situation improved. At noon, Masséna’s troops attacked Dego.

During the assault, the daring Murat led his first charge in a major battle. Bonaparte had sent this staff officer charging with two squadrons of dragoons. Murat’s wild dash into the Austrian ranks was so effective that he was later mentioned with honor in the victor’s dispatch to the Directory. Masséna took most of the 5,000 Austrians prisoner, along with 19 guns. Meanwhile Cosseria Castle fell, and Colli at last could be attacked openly. Leaving Masséna to occupy Dego, Bonaparte retraced his steps westward with La Harpe, hoping to meet Sérurier’s division near the town of Ceva.

But Masséna’s men of the exposed French right flank had been so joyous in victory that they had left their positions to plunder and forage for food. In the early hours of April 15, the French Army in this disorganized state was taken by surprise by five Austrian battalions under General Josef Wukassovitch, who had received orders erroneously commanding his appearance at Dego on the 15th instead of on the 14th. The Austrian attack was catastrophic for the French. According to Ségur, Masséna himself narrowly escaped half-naked in his nightshirt from the bed of his beautiful conquest. Masséna’s men were routed and all of their guns lost.

Napoleon Pursues Colli and His Piedmontese Forces

Once again, Bonaparte canceled his assault on Ceva and, urging on the reserve and the 8,000 cursing troops of La Harpe, advanced to recapture Dego. During this attempt, Chief-of-Battalion Jean Lannes fought with such reckless bravery that Bonaparte promoted him instantly to the rank of colonel.

The French suffered a further loss of a thousand casualties, but they secured Dego, and on the left flank Sérurier and Augereau succeeded in driving Colli back from Montezemolo to Ceva. From the heights of Montezemolo young Bonaparte encouraged his men by remarking, “Hannibal crossed the Alps; we have turned them!”

On April 16, the “Proud Brigand” Augereau vigorously but prematurely assaulted Colli’s Piedmont army at Ceva and was repulsed with heavy losses. Leaving La Harpe’s men to garrison Dego, Bonaparte ordered Sérurier and Masséna to join Augereau’s attack. Colli, wisely noting this threat to his flanks, quickly retreated to Mondovi. Bonaparte then consolidated his forces to the left and opened a new line of communication along the Tanaro Valley to Ormea.

Meanwhile, having grasped the completeness with which Bonaparte had cut him off from his Austrian allies commanded by the slow-moving Beaulieu, General Colli strengthened his position at Mondovi by destroying the bridges and erecting stone fieldworks instead.

Bonaparte opened the major assault on the Piedmontese forces at Mondovi on April 21. Old Sérurier charged Colli’s position from the left, Masséna moved up in front, and Augereau led the flank attack. During one skirmish, the most experienced French cavalry officer, Stengel, was mortally wounded. Murat, now leading the cavalry, threw back the Piedmontese and pursued them onto the plain for hours. As for the French infantry, nothing could stop the ancient warrior Sérurier.

According to Marshall Marmont: “To form his [Sérurier’s] men in three columns, put himself at the head of the central one, throw out a cloud of skirmishers, and march at the double, sword in hand, ten paces in front of his column; that is what he did. A fine spectacle, that of an old general, resolute and decided, whose vigor was revived by the presence of the enemy. I accompanied him in the attack, the success of which was complete.”

The victorious Battle of Mondovi was the turning point of the campaign that had begun just 10 days earlier. As the French advanced on Turin, King Victor Amadeus II asked for peace terms on April 23. By April 28, the Armistices of Cherasco had been agreed upon, ceding control of Piedmont to the French. Colonel Murat was sent to the Directory with the details of the terms of the armistice.

An exuberant General Bonaparte addressed his men on April 26: “Soldiers! In 15 days you have gained six victories, taken 21 standards and 55 guns, seized several fortresses, and conquered the richest parts of Piedmont. You have captured 15,000 prisoners and killed and wounded more than 10,000! … Thanks be to you, soldiers! … You all in returning to your villages will be able to say with pride: ‘I was of the conquering Army of Italy.’”

Through brilliant concentration of his forces at critical places and times, the resolute French commander had beaten one Austrian enemy and pushed him into Lombardy, while forcing the second enemy from Piedmont to sue for peace. He may have been outnumbered by these enemies, but through his cunning economy, tight security, omnipresent galloping from column to column, and constant encouragement and direction of every movement, Napoleon had gloriously fulfilled his promises of March. He had demonstrated his unequaled determination and audacity with his “strategy of the central position.” Although he faced such serious setbacks as those at Cosseria and Dego, in only two weeks he had achieved all of his preliminary objectives. Clearly, this was a notable young commander.

Onward to Milan

The French Army now paused for reorganization and preparation for an offensive directly against Beaulieu. During the delay, Beaulieu evacuated Alessandria and crossed the Po River at Valenza. Bonaparte, having reinforced his army to 36,000 by acquiring the troops of Generals François Macquart and Pierre Garnier, also opened his line of communication with the Col Di Tende.

But Bonaparte now faced a difficult problem. He must cross the Po without a bridging train, all the while facing Beaulieu’s army. He decided to rush his troops across the Po at Piacenza, 50 miles from Valenza, thereby surprising Beaulieu’s Austrians. Masséna and Sérurier mounted a diversionary operation at Valenza while a special “Corps D’Elite” of select Grenadiers commanded by General Claude D’Allemagne were to rush to Piacenza and establish a bridgehead there.

On May 7, Colonel Lannes, the first man to cross the Po, led D’Allemagne’s advance guard of four battalions over to the north bank. When Beaulieu received news of the French crossing he ordered up the available Austrian forces of Generals Anton Liptay and Wukassovitch.

On the morning of May 8, D’Allemagne clashed with Liptay. That night Beaulieu’s converging columns came into violent conflict with French troops at Codogno, and during the confused night action French General La Harpe was killed by shots fired by his own men. Chief-of-Staff Berthier took personal control of the battle and Beaulieu ordered a full retreat over the River Adda at Lodi.

The fall of Milan was certain; nevertheless, Bonaparte pushed his men toward Lodi. The French arrived on May 10 to find the whole Austrian Army safely across, leaving 10,000 men of General Carl Philipp Sebottendorf as a covering force. These troops and a dozen cannon could sweep the bridge with devastating crossfire. Napoleon’s answer was a flaming speech to his men and leading a charge of Grenadiers. The charge failed but was renewed as all the senior officers charged at the head of the column crying, “Vive La Republique!” This charge was successful.

The Bridge at Lodi was a major turning point for the Army of Italy and its young commander. At Lodi, Bonaparte earned the confidence and loyalty of his men, who thereafter nicknamed him “Le Petit Corporal” in recognition of his personal courage, determination, and example. For Napoleon the event was also a personal triumph and transformation. “It was only on the evening of Lodi,” he recorded a long time later, “that I believed myself a superior man, and that the ambition came to me of executing the great things which so far had been occupying my thoughts only as a fantastic dream.” A few days after Lodi, at Milan, Napoleon confided to Marmont, “They [the Directory] have seen nothing yet.… In our days no one has conceived anything great; it is for me to set the example.”

But the Directory was already jealous of Napoleon’s success and, in a dispatch received the night of May 10, he learned that his masters had decided to split command of the Army of Italy between him and François Kellermann. The young man refused and explained that all would be lost, because one bad commander was better than two good ones. Accompanying the letter was another large convoy of plunder for his masters at the Directory; the politicians backed down. Moreover, Kellermann graciously sent 10,000 reinforcements together with his own son to serve on Bonaparte’s staff.

One month and two days since opening the campaign, Bonaparte entered Milan to a hero’s welcome. But the popular acclaim did not last long. Covetous of hard cash, supplies, and art treasures, the Army and French government plundered the city.

The Pursuit of Beaulieu

On May 22 the French Army left Milan to again seek Beaulieu, although two days later the Army had to return to Milan and Pavia to put down local revolts. This accomplished, the town of Borghetto was stormed on May 30 and Beaulieu’s forces were scattered. During this skirmish Captain Béssières distinguished himself by jumping from his fatally wounded horse onto an Austrian gun and capturing it. This coolness under fire later made Béssières the perfect commander of the special formation of guides to protect the French general-in-chief. Clearly the commander was in need of protection. He was almost captured on June 1 when Sebottendorf’s scouts surprised him and his staff in the village of Valeggio. The young general made his escape with one boot off as he vaulted several garden walls. In time, Béssières’ guides would become the famous “Regiment Des Chasseurs A Chéval” of the Imperial Guard.

The French rapidly exploited their success at Borghetto as Augereau advanced on Peschiera, Sérurier advanced first on Castel Nuova and then on the great fortress of Mantua, and Masséna seized Verona. According to the historian Adlow, “Beaulieu was not driven out of Lombardy; it would be more appropriate to say he was frightened out.” Beaulieu retreated up the shores of Lake Garda to Trent, but 4,500 of his men were cut off and driven into Mantua. The first siege of Mantua, which controlled the plains of northern Italy, was soon under way.

Mantua was an imposing fortress of 316 guns and a garrison of 12,000 men. In undertaking a siege, the Army of Italy would now become a defensive force protecting its potential conquest of Mantua against repeated Austrian attempts to relieve the garrison. General Bonaparte’s mastery of offensive warfare had been demonstrated. Now his abilities to sustain a strategic defense against continuous superior enemy forces would be severely tested. The siege of Mantua would last eight months.

A French attempt to storm the city was unsuccessful on May 31, and by June 3 Mantua was fully invested by Sérurier, Augereau, D’Allemagne, Lannes, and General Charles Kilmaine’s cavalry. During the next few weeks Bonaparte collected art treasures from the Papal States and Tuscany and, more importantly, he gathered large cannon from Fort Urban and other cities of Tuscany for the Mantua siege. On June 29 the beautiful Josephine joined her husband in Milan. “Then,” says Marmont, “he lived only for her.… Never has a truer, a purer, a more exclusive love possessed the heart of a man.”

But on this same day the first Austrian push to relieve Mantua began. General Count Dagobert Wurmser took command of Beaulieu’s 50,000 soldiers. Wurmser’s army advanced in three separate corps, each driving down a side of Lake Garda and the Brenta Valley. On July 29 the central column pushed Masséna out of Verona. Moving on the west shore of Lake Garda, Austrian General Peter Quasdanovitch was checked by Augereau at Brescia on August 1. The situation became sufficiently grave for General Bonaparte to order the concentration of every available man to reinforce his overwhelmed northern front. To meet Wurmser’s Austrian offensive, the siege of Mantua had to be abandoned and the large guns captured from Tuscany had to be spiked, buried, and even left to the Mantua garrison that was now free to operate and attack the French rear. Personally, the French commander was despondent.

But because Wurmser was moving on Castiglione, and Quasdanovitch was on the western shore of Lake Garda, Bonaparte was again offered the opportunity of central position. If time would afford, he would attack each wing of the Austrian Army before they could unite. Thus, while Wurmser delayed at Valeggio for three days, Bonaparte planned his attack, with the ensuing August 3 Battle of First Lonato the result. To begin, Masséna fought off Quasdanovitch while Augereau ferociously battled Wurmser’s advance guard near Castiglione. Augereau covered himself with glory; he held Liptay and prevented both Liptay and Wurmser from aiding Quasdanovitch. For this success Augereau would become the future “Duke of Castiglione.”

Then, while Masséna was hotly engaged with Quasdanovitch—who had lost one division—Bonaparte threw all his troops upon Wurmser. Masséna’s victorious soldiers were brought up on Augereau’s left, and Sérurier’s troops—having evacuated the Mantua siege lines—were to fall on Wurmser’s flank. On August 5 the three French divisions of 30,000 men fell upon Wurmser’s 25,000 unsuspecting Austrians at Castiglione. Both Augereau and Masséna’s troops were ordered to give ground. This was a very dangerous tactic, but the troops had confidence in their “Little Corporal” and they were now better trained. At a given signal, General Pascal Fiorella, commanding the ill General Sérurier’s division, was unleashed on Wurmser’s flank. The Austrians lost 20 cannon, 120 caissons, a thousand prisoners, and 2,000 killed and wounded, but managed their retreat only because the French, who had fought continuously for three days, were completely exhausted.

The Battle of Bassano

Having blunted this offensive, the French could once again besiege Mantua. This they did with 10,000 men under Jean Sahuguet, 3,000 men of General Kilmaine guarding Verona. The main French Army of 33,000 men led by Claude Vaubois, Masséna, and Augereau then advanced on Trent to pursue Wurmser.

Wurmser gathered his 20,000 troops from Trieste and 25,000 men under Baron Paul Davidovitch to defend Trent and the Tyrol. As the Army of Italy advanced up the Adige River, Vaubois and Masséna forced back 14,000 of Davidovitch’s troops at Roverdo on September 4. Bonaparte then learned that Wurmser was now on his way to relieve Mantua, and on September 6 the advance into the Tyrol was canceled in favor of the pursuit of Wurmser.

The Battle of Bassano on September 8 saw the Austrians unable to withstand the furious onslaught of Colonel Jean Lannes that burst through the Austrian lines and stormed into town. Murat’s cavalry pursued the fleeing enemy, taking 4,000 prisoners, 35 guns, five colors, and two pontoon trains. Part of Wurmser’s beaten battalions fled toward Frioul. Others, including Wurmser himself, fought their way into Mantua on September 12. This reinforcement raised the city garrison to 23,000 men but proved a mixed blessing because now there were more mouths to feed. In his excitement to relieve Mantua, Wurmser had ended up by incarcerating himself within its walls.

Despite this achievement, the situation of the Army of Italy remained difficult. Reinforcements were slow, and by October the French counted only 41,000 men. Of these 9,000 under Kilmaine surrounded Mantua, and 14,000 troops were sick. Mantua now had 23,000 Austrians ready to strike the French rear. Bonaparte took measures to protect the area against surprise attack. Vaubois’s 10,000 men were stationed at Lavis to block the Lake Garda approaches. Masséna occupied Bassano and was in contact with Vaubois throughout the Brenta Valley. Bonaparte was with Augereau in reserve at Verona.

During this period of military inactivity, the young Bonaparte turned his attention to administrative matters. He began the unification of Italy by establishing three new republics: the Cisalpene, comprising the Milanese; the Cispadene, combining Modena and Reggio; and the Transpadene, joining Bologna and Ferrara. Bonaparte eventually planned to unite these three states into a single North Italian Republic but he faced enormous hostility from various vested interests, namely the Church, the nobility, and the well connected. Thus Italy would remain divided into city-states for generations.

These political problems were soon overshadowed once the new Austrian Army of 46,000 men under Baron Joseph D’Alvintzi began to move against the French, who still had the 23,000-man Austrian garrison of Mantua to its rear. The Austrian offensive began in November with D’Alvintzi’s army of 28,000 marching toward Bassano and 18,000 under Davidovitch attacking Trent. Bonaparte deduced the Austrian plan, but his information was not accurate in terms of actual enemy troop strength.

Bonaparte ordered Vaubois to attack Trent. Vaubois responded that Davidovitch was far stronger than anticipated. Bonaparte then ordered Vaubois to hold ground while he planned on driving the Austrian D’Alvintzi out of the Brenta Valley before falling on Davidovitch’s rear. Unfortunately, Vaubois was routed by Davidovitch on November 4; Trent and Roverdo fell to the enemy also. Vaubois managed to rally his fleeing men at Rivoli. Meanwhile, Masséna gave ground to the advancing D’Alvintzi, who captured Bassano, Fontanove, and Vicenza. Bonaparte ordered Masséna to fall back to the “central position” of Verona, there joining Augereau. He ordered Joubert to reinforce Vaubois’s shaken troops at Rivoli.

Bonaparte then traveled to Vaubois at Rivoli and issued the following rebuke:“Soldiers! I am not satisfied with you. You have shown neither discipline, nor constancy, nor bravery; in no position could you be rallied. You abandoned yourselves to a panic terror. You have allowed yourselves to be driven from positions where a handful of brave men should stop an army. Soldiers of the 39th and of the 85th, you are not French soldiers. General, Chief of Staff, cause to be written on the flags: ‘They are no longer the Army of Italy!’” The punishment hit home and Vaubois’s ashamed soldiers vowed to conquer or die.

During the next few days, Davidovitch did not move. But D’Alvintzi marched quickly to Verona. Soon 8,000 Austrians occupied Caldiero and Colognola. Bonaparte ordered Augereau to attack the right and Masséna the left on November 12. After a bitter fight these two carried the villages of Caldiero and Colognola, but D’Alvintzi arrived with his main force and recaptured both villages with his superior numbers. The Austrians captured two cannon and 750 prisoners, the French losing a total of 2,000 men. Napoleon abandoned the field and retired to Verona, having tasted his first defeat since the Italian Campaign started. Faced by 50,000 men in his front and 23,000 men at his rear at Mantua, a despairing General Bonaparte wrote to the Directory, “Perhaps the hour of the brave Augereau, of the intrepid Masséna, of my own death is at hand. We are abandoned in the depths of Italy.”

Although he was distraught, Bonaparte outwardly encouraged his troops by proclaiming: “We have but one more attack to make and Italy is our own. The enemy is, no doubt, more numerous than we are, but half his troops are recruits; if we beat him, Mantua must fall, and we shall remain masters of everything.”

Out of Defeat, A New Plan

During this most strategic uncertainty Napoleon revealed his greatest talents. He set out to defeat the 23,000-man force of D’Alvintzi with the 18,000 men of Augereau and Massena’s commands—all the other French troops were required to bottle up Mantua or hold Davidovitch.

Bonaparte’s brilliant plan was “Une Manoevre Sur Les Derriéres”—attacking the enemy’s rear as he had done against Beaulieu at Lodi and Wurmser at Bassano. He would rush all available troops from Verona to seize Villa Nova and capture D’Alvintzi’s field park, convoys, and lines of communication. If he could do this, then he would be able to choose the ground for battle. The Austrians would not be able to employ advantage of number. They would find themselves on a narrow front in a marshy area surrounded by the Alpone and Adige Rivers, making it almost impossible to deploy.

Leaving General François Macquard with Vaubois’ 3,000 men to defend Verona, Bonaparte set off on the night of November 14 to Ronco with 18,000 men. By morning, French chief engineer Antoine Andreossy had thrown a pontoon bridge over the Adige River. Augereau was first to cross on his way to Arcola. Masséna followed and moved left to successfully take Porcile from Provera’s Austrian advance guard. The great difficulty of the day arose when Augereau was faced at the Arcola Bridge by two battalions of Croatian infantry and several guns sweeping the roadway. This check was destroying Bonaparte’s timetable and he was fast losing the element of surprise. Desperate, he seized the colors, and with banner flying led Augereau’s men forward. In the fire and confusion the young general fell into a canal and only the devotion of his aides-de-camp saved him from the bayonets of the Austrian counterattack.

Eventually, Guieu’s troops captured Arcola at 7:00 pm, six hours too late; D’Alvintzi retreated from Verona to Villanova. The opportunity to capture him had passed, and distressing news that Vaubois had been driven back to Bussolengo caused Bonaparte to give up Arcola in case he must rush to relieve Vaubois. The general had stopped D’Alvintzi’s threat to Verona and kept him from joining Davidovitch. Still, he had wanted so much more—except for the delay in crossing the bridge at Arcola his plans for D’Alvintzi’s entrapment were excellent.

The next morning Bonaparte renewed the attack on Arcola. The French also recaptured Porcile, which the Austrians had reoccupied. On the third day of fighting, November 17, with no disturbing news from Vaubois, the French unleashed all their fury against the army of D’Alvintzi, which was disposed in two unconnected parts under Marchese Giovanni Provera and Prince Frederich Hohenzollern. Bonaparte now had numerical superiority over each enemy wing. Masséna took Ronco and then lured the Austrian garrison out of Arcola, falling on them in an ambush, causing heavy enemy casualties. Augereau pushed aside the other wing and joined Masséna’s victorious division.

Faced by this major attack on his rear positions, D’Alvintzi retired immediately to Vincenza leaving 7,000 casualties in the three-day struggle at Arcola. Bonaparte, taking advantage of his central position, turned his army toward Davidovitch. Seeing his peril, Davidovitch just escaped Augereau at Dolce on November 21, leaving 1,500 prisoners, nine cannon, two bridging trains, and his baggage.

So ended the third Austrian counteroffensive. Bonaparte had again masterfully used the strength of interior lines engaged in a vigorous offense against a divided exterior and numerically superior forces. The Army of Italy responded eagerly to its leader, who had exhibited personal bravery at Lodi and Arcola and commanded in such a way as to beat one Austrian army after another. German military strategist Von Clausewitz wrote about Arcola: “What … turned this hotly contested battle into a victory for Napoleon? It was a better use of the elements of tactics, a greater bravery in the field, a superior mind, and a boldness without any limits.”

It was also the great devotion the army felt for its commanding general. An example can be seen in Bonaparte’s letter of November 19 to Citizen Carnot: “Never was a battlefield disputed like that of Arcola. I scarcely have any generals left; their devotion and their courage are without example. General of Brigade Lannes came to the battlefield not yet healed of the wound he received at Governolo. He was wounded twice during the first day of the battle. He was at three in the afternoon stretched on his bed and suffering, when he learned that I myself was going to the head of the column. He jumped from his bed, mounted his horse, and came to join me. As he could not stay afoot, he was obliged to remain on horseback. He received at the head of the bridge of Arcola a wound which stretched him lifeless. I assure it needed all that to win.…”

Nevertheless, the Austrians, though they had been driven back to Bassano and the Tyrol, were sure to return once again in hopes of averting the fall of the great fortress of Mantua. The French government began negotiations with the Austrian Emperor, but once the issue of sending provisions to Mantua was mentioned, these talks went no further.

Subsequently, the French Army received reinforcements and could put 34,500 men into the field in addition to the 10,000 men besieging Mantua. Communication between the various detachments was improved by use of courier posts and cannon shot. The disposition of the French units had Joubert between La Corona and Rivoli on the east side of Lake Garda, Masséna at Verona, Augereau south of Ronco on the lower end of the Adige River, and General Antoine Rey on the west shore of Lake Garda. Sérurier returned to the Mantua siege, relieving the ill Kilmaine, and Vaubois was relegated to the minor command of Leghorn.

Meanwhile the Austrian D’Alvintzi had been reinforced in Bassano to 45,000 troops. Thus strengthened he commenced diversionary attacks on Augereau on January 8, 1797, pushing him back on Legnano and clashing with Masséna at Verona. Still the Lake Garda sectors remained suspiciously quiet. Bonaparte waited for D’Alvintzi to show his hand, which he did by moving with 28,000 men to crush Joubert in the Adige Valley. Seeing this, Bonaparte left 3,000 men to garrison Verona and hurried with the remainder of the French Army north to Rivoli.

The Battle of Rivoli

As had happened once before, the terrain provided several good roads for the French to travel north, but the Austrians traveling south would find only two roads for troops, artillery, and trains. And once again Austrian slowness played into the hands of the fast-moving French Army and their quick-thinking young general. The battle would be a race against time; everything depended on the speed of reinforcements as they were progressively committed to the battle.

The Battle of Rivoli began at daylight on January 14 when French General Joubert advanced his 10,000 men and 18 cannon to drive back the 12,000 Austrians in three columns under Generals Ocksay, Koblos, and Liptay. At first all went well, but Koblos managed to check Joubert’s advance and then Liptay began to outflank Joubert’s left. Masséna was ordered to shore up the Frenchmen. He was almost captured by the advancing Austrians who called “Prisoner! Prisoner!” With superb calm Masséna turned his back on his pursuers and rode off whistling to meet his own troops. He then stabilized this critical position.

Soon, however, the French were threatened by Quasdanovitch’s 7,000-man Austrian column on the important Osteria Gorge. In addition to this crisis on the right, the Austrians of Lusignan’s column were now south of Rivoli and in the French rear. To open the line for reinforcements from General Rey, commander Bonaparte addressed the 18th Demibrigade. “Brave 18th!” he cried, riding up. “I know you. The enemy will not stand up before you.” Masséna then followed with, “Comrades, in front of you are 4,000 young men belonging to the richest families of Vienna; they have come with post-horses as far as Bassano: I recommend them to you.” With a roar of laughter, the troops charged Lusignan crying, “En avant!”

As the northern and southern battle sectors became secure, Bonaparte directed Joubert’s realigned brigades to meet the eastern threat by Quasdanovitch at the Osteria Gorge. The concentrated Austrians could not deploy and made an easy target for the light-artillery batteries that poured case shot into them at point-blank range. Two Austrian ammunition wagons exploded, causing terrible carnage and confusion in the cramped enemy body. A charge by Lasalle and Leclerc of 500 French infantry and cavalry cleared the gorge. This accomplished, the entire French Army was rushed back to the northern sector, splitting the Austrians in two. Reinforcements arrived under General Rey and these soldiers, together with Masséna’s reserve brigade, captured 3,000 of Lusignan’s Austrians in the south.

The battle was nearly won when Bonaparte turned it over to Joubert in the evening. Then he and Masséna hurried farther south to prevent Austrian General Provera’s 9,000 men from trying to break through to Mantua. Sérurier’s troops blocked Provera, and though Wurmser attempted to break out on January 16, Provera found himself with Bonaparte and Masséna in his rear. Provera had no choice but to capitulate. In five days of fighting, January 14–19, Bonaparte had reduced D’Alvintzi and Provera from 48,000 fighting men to 13,000 fugitives. The fall of Mantua was completed on February 2, 1797, when the garrison surrendered—only 16,000 of 30,000 were able to march out.

Thus Napoleon Bonaparte had achieved his great objective. But now the Austrian Archduke Charles began assembling 50,000 troops in the Frioul and the Tyrol. Without waiting for reinforcements, Bonaparte planned a two-prong advance upon Vienna with himself and Joubert leading converging French columns. He was going to be relentless in pushing his men onward to force the Austrians back before they could mount another offensive.

On March 1, Masséna, Guieu, Bernadotte, and Sérurier’s divisions forced the capitulation of Primolano. The town of Sacile on the Tagliamento River was taken March 16 after Guieu, who replaced Augereau, and Bernadotte surprised the Austrians. Next Tarvis and then Trieste with its great arsenal fell to the rapidly advancing French. On April 18, the Preliminaries of Leoben were opened, and by October 17, 1797, the final Peace of Campo Formio was signed by Austria and France. Among the many provisions in the treaty was Austria’s recognition of Bonaparte’s creation of the new Cisalpine Republic comprising Milan, Bologna, and Modena.

An Amazing Year

During this amazing year, French armies on the Rhine were failing, but Bonaparte was succeeding. The reason was that the young leader showed mastery of both offense and defense, of strategy and tactics. His continued and brilliant use of central position and the vital concentration of all forces at the right place and at the right time led to the successful destruction of four Austrian attempts to relieve Mantua. His concentrations were achieved by the mobility and surprise of the fast-marching French soldiers and the determination and fighting abilities of Bonaparte’s lieutenants—Masséna, Augereau, Sérurier, Joubert, and the rising stars, Murat, Béssières, and Lannes.

Still, it was Bonaparte at the helm. General Henry Clarke, representing the Directory during his visit to the French Army of Italy, reported back to Paris: “The General-in-Chief has rendered the most important services.… The fate of Italy has several times depended on his learned combinations. There is nobody here who does not look upon him as a man of genius, and he is effectively that. He is feared, loved, and respected in Italy.… A healthy judgement, enlightened ideas, put him abreast of distinguishing the true from the false. His ‘coup d’oeil’ is sure. His resolutions are followed up with energy and vigor. His ‘sang-froid’ in the liveliest affairs is as remarkable as his extreme promptitude in changing his plans when unforeseen circumstances demand it. His manner of executions is learned and well calculated. Bonaparte can bear himself with success in more than one career. His superior talents and his knowledge give him the means.… Do not think, Citizen Directors, that I am speaking of him from enthusiasm. It is with calm that I write, and no interest guides me except that of making you know the truth. Bonaparte will be put by posterity in the rank of the greatest men.”

He was 27 years old and, as he had said in this fateful year, they “had seen nothing yet.”

My favorite novel is Tolstoy’s “War and Peace”; though Tolstoy tries to prove that history drives men and not the other way around, Napoleon’s actions do not support Tolstoy’s thesis.