By Eric Niderost

When Lt. Col. Lord George Paget rose early in the morning of October 25, 1854, he had no inkling of, as he later put it, “the day’s work in store for us.” Paget was part of an Anglo-French expeditionary force now besieging the Russian naval base at Sevastopol on the Crimean peninsula. Lord George was also brevet colonel and the head of the 4th Light Dragoons.

It was about an hour before daybreak, and as usual the whole British Cavalry Division turned out and were standing by their horses. A pale gray smear brought the Crimean hills into sharp relief, harbinger of the morning sun, but at this early hour all else was plunged into gloom. Suddenly, movement stirred the predawn darkness, shadowy, spectral figures that Paget identified as Lt. Gen. George Bingham, Third Earl of Lucan, and his staff.

Lucan was the commander of the entire cavalry division, but his presence at such an early hour caused no concern. In fact, it was his custom to inspect the outposts that guarded the British supply base at Balaklava. Paget decided to follow his chief, though at a respectful distance of some 50 yards. Lord William Paulet and Major McManon joined Paget in this nocturnal excursion.

The small knot of British officers rode across a broad plain past a series of hastily constructed Turkish redoubts. Britain had come into the war in part to protect Turkey from Russian encroachments, but few Britons had any confidence in the Turkish Army. Lord Lucan had received disturbing reports that the Russians were massing troops to the northwest, ominous indications that the Czar’s forces might launch an offensive against Balaklava. Blissfully ignorant of his chief’s concerns, Paget caught sight of the looming mass of Canrobert’s Hill, named after an allied French general. The hill was crowned by Redoubt No. 1, now strongly silhouetted against the lightening sky.

Redoubt No. 1’s flagstaff was flying two flags, but their significance was a subject of much debate. “Holloa,” cried Sir William, “there are two flags flying—what does that mean?” “Why, that surely is the signal that the enemy is approaching,” answered McManon with an air of confidence. “Are you quite sure?” Paget and Paulet replied almost in unison, but their chorus of doubts was cut off by a large cannon blast from Redoubt No. 1. It was firing on Russian infantry on the other side of the hill, and as yet unseen by the British officers.

The Ottoman Decline Aroused Czar Nicholas I’s Predatory Instincts

The booming report echoed through the gray-tinged dawn, the gradually fading sound soon followed by a succession of other cannon reports. These salvoes were the first shots in what would become known to history as the Battle of Balaklava.

Britain and Russia had been staunch allies against France during the Napoleonic Wars 40 years earlier. What had brought about this startling reversal of alliances? Miscalculation, power politics, and ambition all played their part in the coming tragedy, but the catalyst was the Ottoman Empire’s rapid decay throughout the course of the 19th century.

The Ottoman decline aroused Czar Nicholas I’s predatory instincts. Calling Turkey the “sick man of Europe,” he eagerly anticipated the spoils that would come to Russia when the patient finally drew his last breath. Turkey’s Danubian principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia (today’s Romania) seemed ripe for the plucking, and the Czar expressed an interest in establishing a “protectorate” in Serbia and what is now Bulgaria. A prisoner of climate and geography, landlocked Russia long coveted access to the Mediterranean.

Great Britain had its own reasons for opposing the Russian Czar. The Industrial Revolution had transformed Britain into the leading economic power of Europe. British prosperity, power, and prestige depended on maintaining, and even expanding, its overseas markets. Although the Suez Canal had not yet been built, the Mediterranean was Britain’s lifeline to India and beyond. In 1843 Thomas Waghorn blazed a trail across the Egyptian desert to Suez. From there, passengers could board steamers that took them to India.

Almost overnight India and the rest of Asia were more accessible. Before 1843, the route to India was around Africa via the Cape of Good Hope, a journey of 16,000 miles that could take as long as six months. Waghorn’s Mediterranean-Egypt-Suez route was only 6,000 miles and took around 40 days. Keeping the Mediterranean sea lanes open and free of Russian domination became a cornerstone of British foreign policy.

Overconfident and ambitious, Czar Nicholas sent Russian troops to occupy Turkey’s Danubian principalities. When the Sultan’s demands to withdraw were rejected, the Ottoman Empire declared war on Russia. Fearing the consequences of a resurgent Russia, France and Britain followed suit and declared war on Russia on March 27, 1854.

On September 14, 1854, a joint British, French, and Turkish force of 60,000 men landed on the Crimean peninsula at Calamita Bay. Their target: the great naval base at Sevastopol, which was the home port of the Russian Black Sea Fleet and a major component in the Czar’s Mediterranean ambitions. The allies landed about 30 miles from Sevastopol, but their debarkation was entirely unopposed—Prince Alexander Sergeevich Menshikov, entrusted with the defense of the Crimea, was taken by surprise.

Russian Morale Began to Plummet Following the Loss

The allies then won a hard-fought victory at the River Alma, but in its aftermath some golden opportunities to capture Sevastopol were lost. The Alma came as an unexpected shock to the overconfident Russians, so much so that morale plummeted among the troops and some units were close to mutiny. On September 25 Menshikov decided to withdraw the bulk of the Russian Army from Sevastopol so it would not be bottled up when the fortress came under siege. Most of the Czarist forces withdrew to the east, forming a field army that could threaten the allies’ rear when the siege finally took place.

The withdrawal was strategically sound, but left only about 18,000 men—mostly sailors from the defunct Black Sea Fleet—to garrison Sevastopol. If the allies had acted swiftly, they might have taken the naval base.

But the opportunity was lost after two Russian leaders emerged from the chaos. Lieutenant Colonel Franz Edouard Ivanovich Todleben, a brilliant engineer, became the heart of Sevastopol’s defense by constructing a series of new fortifications. And Admiral Vladimir Alexeevich Kornilov became its soul, bolstering morale with his fierce exhortations and fervent appeals to national pride. A young artillery officer, Count Leo Tolstoy, noted that Kornilov would say, “Lads, we will die, but we will not surrender!” and the soldiers would reply, “We will die! Hurrah!” Tolstoy’s firsthand experiences in the war would provide material for his classic novel War and Peace.

Thus the allies had to resort to siege operations, landing heavy guns and stocking ammunition. The French took the undefended harbor at Kamiesh as their main supply base, while the British chose Balaklava.

A small town, Balaklava nestled beside a narrow arm of the Black Sea. The inlet was surrounded by a series of massive hills, towering peaks so large they blocked the view of the sea and made the waterway seem more like an inland lake. In any event, because Balaklava was the main British supply base, its maintenance was of the utmost importance.

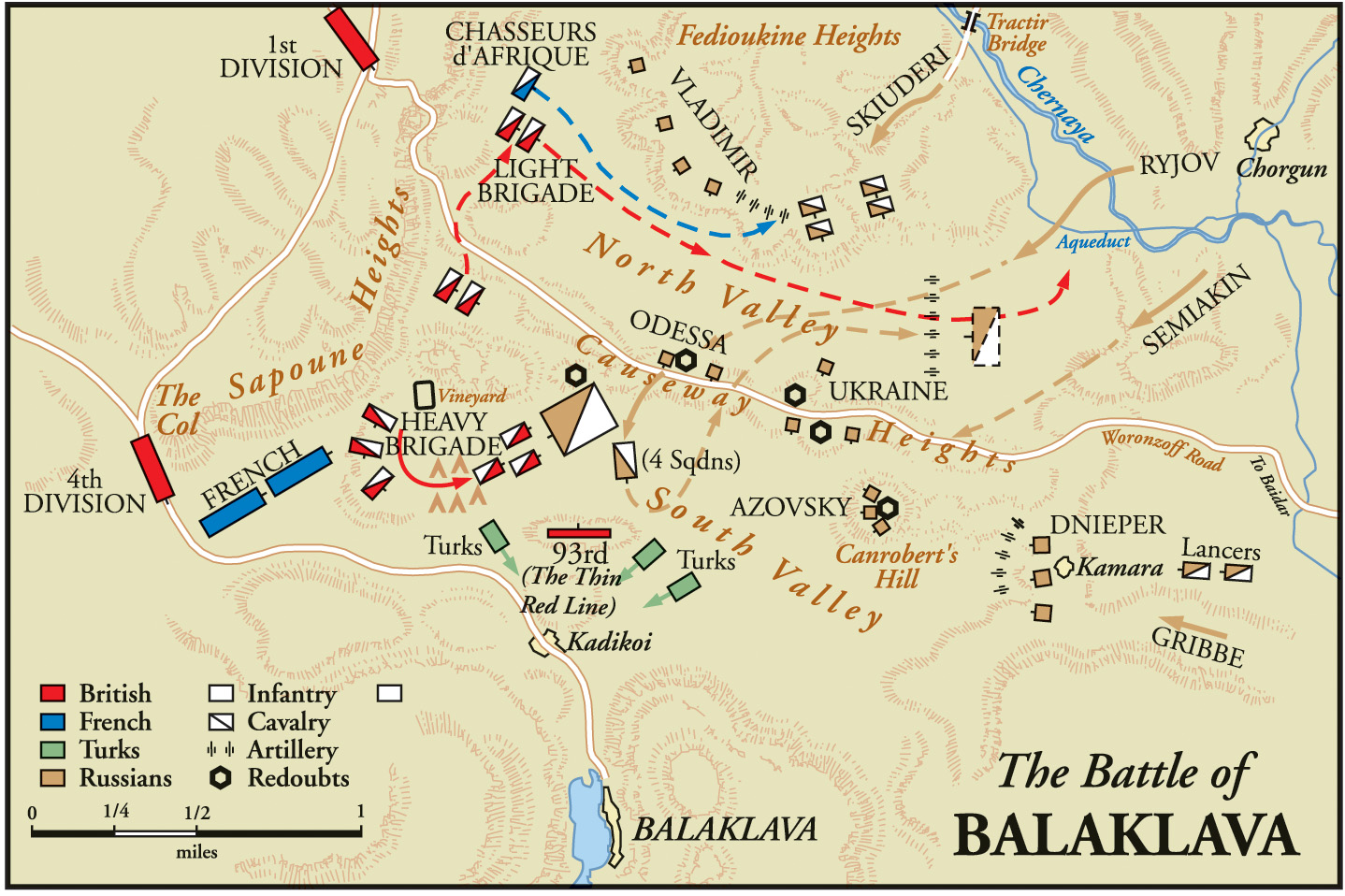

Geography was going to play a decisive role in the coming battle. A broad plain stretched just to the north of Balaklava, its boundaries marked by a series of undulating hills. The Sapoune Heights, which rose in the west, were the fringe of the great Chersonese Plateau where Sevastopol siege operations were currently taking place. The Balaklava Plain itself was divided by a narrow ridge that the British dubbed Causeway Heights. The Woronzoff Road snaked along part of this hilly backbone, which led to the hunting lodge of a Russian noble by the same name.

Causeway Heights neatly separated Balaklava Plain into two valleys, appropriately dubbed North Valley and South Valley. Much of the coming drama would be played out in these two valleys. The bulk of the British infantry was busy in the siege lines before Sevastopol, making Balaklava’s defense problematic. The situation was made worse by the ravages of cholera, which was claiming many victims. In order to protect Balaklava, FitzRoy Henry James Somerset, Lord Raglan, opted for a defense in depth, though the strength of his arrangements was more apparent than real.

Each Redoubt Was Assigned 10 British 12-Pounder Cannons

The outer defense perimeter consisted of a series of six redoubts that paralleled, and at times straddled, Causeway Heights. Redoubt No. 1 was on the crest of Canrobert’s Hill, which offered a commanding view of the ridges and hills that erupted to the north and east like the waves of a petrified sea. The Chernaya River flowed through these hills just to the northeast; reports indicated that the Russians were massing in the village just across this waterway.

Redoubt No. 2 was about 1,000 yards behind Canrobert’s Hill, while Redoubts 3 and 4 were just across the Woronzoff Road, their guns facing the North Valley. Reboubts 5 and 6 had not been manned or constructed, and to all intents and purposes were little more than place names on a map. Even the existing “redoubts” were little more than hastily dug earthworks spaded out from the stubborn soil. These flimsy excavations would serve as breakwaters, slowing a Russian flood, but at best they would delay such a torrent, not stop it in its tracks.

The four redoubts were assigned 10 British 12-pounder cannon, three each in Redoubts 1 and 4, two each in the others. The earthworks were manned by 1,500 Turkish troops, but the British had some doubts about their quality. In reality the designation “Turkish” was a military fiction, put forward as a designation of allied cooperation and good will. These troops were largely colonial Tunisians from North Africa, conscripts who had little love for their Ottoman masters.

The Balaklava inner defense position was entrusted to Sir Colin Campbell, commander of the Highland Brigade. Campbell had already packed a lifetime of campaigning in his 60-odd years. Intelligent, talented, experienced, Campbell was one of the few officers who emerged from the Crimea with an enhanced reputation.

A narrow road wound up from Balaklava harbor, the track surrounded on two sides by the coastal mountain range like the neck of a bottle. The road eventually led to the village of Kadikoi, where lay the heart of Campbell’s defense. A rise poked up just north of the village, a perfect “cork” to the Balaklava bottleneck, if sufficient artillery could be placed there.

Campbell’s own 93rd Highlanders were billeted in Kadikoi, along with a battalion of Turks. Captain George R. Barker’s W Battery, Royal Artillery, was soon sited at the “cork” just north of the village. Mt. Hiblak—later called Marine Heights—formed the right edge of the “bottle.” Some 1,200 Royal Marines were stationed here, as well as five batteries (23 guns) of the Royal Marine Artillery. The hills that formed the left edge of the “bottle” had the guns of Lieutenant Wolf’s Royal Artillery.

Czar Nicholas brooded over the Battle of the Alma, ultimately ordering Prince Menshikov to launch an immediate offensive that would wipe out the stain of that defeat. But where could Menshikov attack?

Baklava’s Force Consisted of 25,000 Infantry, 34 Squadrons of Cavalry, and 78 Pieces of Artillery

Balaklava seemed lightly defended. Those Turkish redoubts didn’t seem very formidable, and once they were taken, the Russians could sweep on to threaten Balaklava itself. Why, the Russians didn’t even have to take physical possession of the port proper; if they seized Kadikoi Village they would cut the British supply line and render Balaklava untenable.

Thus the scenario was set. The Balaklava offensive was assigned to Lt. Gen. Pavel Liprandi’s field army. This force consisted of 25,000 infantry, 34 squadrons of cavalry, and 78 pieces of artillery. Liprandi began concentrating his forces around Chorgun, just beyond the Chernaya River. The Russian plan consisted of two distinct phases, and each part of Liprandi’s army had a distinct and interlocking role.

The first phase envisioned a left column under Maj. Gen. S.I. Gribbe moving forward and taking Kamara Village. Once in place, the guns of the 8th Light Battery and the 4th Battery would unlimber and start a heavy barrage on Redoubt No. 1.

Once this action started, Maj. Gen. K.R. Semiakin’s center column would be divided in two. Semiakin would personally direct assault operations against Redoubt No. 1, while his subordinate, Maj. Gen. F.G. Levutsky, would take Redoubt No. 2. A right column under Colonel A.P. Skiuderi was ordered to capture Redoubts 3 and 4. Taken all together, Phase One would include 14,000 infantry and 36 guns. A covering screen of some 6,400 infantry would be deployed on Fedioukine Heights, which bordered North Valley.

The opening phases of the offensive went like clockwork. The Russians quickly drove in the British pickets and took Kamara Village. They manhandled guns into position, and soon loosed a hurricane of shot and shell upon the redoubt on Canrobert’s Hill. Semiakin, Levutsky, and Skiuderi managed to cross the Chernaya River without incident, and moved quickly into their assigned positions.

There was initially little that the British could do to reply to these maneuvers. An urgent message was dispatched to Lord Raglan informing him of the attack, but in the short run Campbell and Lucan knew they were on their own.

Lucan ordered the Light Brigade to remain in reserve while the Heavy Brigade was sent down to South Valley to stage a series of threatening maneuvers. Without substantial infantry support this was all bluff, but there wasn’t much else Lucan could do at this stage. He did send Captain Maude’s I Troop, Royal Horse Artillery, forward to give the redoubts some support in what was becoming an increasingly unequal artillery duel.

I Troop came forward at a gallop and unlimbered at a position on Causeway Heights not far from Redoubt No. 3. The rising sun was now a blinding orb that shone directly in their eyes, making it difficult if not impossible to discern enemy targets. However, Russian muzzle flashes could easily be seen, even with the sun’s glare, and British 6-pounder guns soon flamed in counterbattery. But Russian gunners quickly realized what was happening and poured a heavy fire down on I Troop. The horse teams took terrible punishment, even though they were partly sheltered by the reverse slope of Causeway Heights.

Captain Maude’s Arm Was Nearly Severed by the Explosion

Russian shells exploded with ear-shattering roars, spraying lacerating shards of metal in every direction. Captain Maude was directing some howitzer fire on advancing Russian skirmishers when a shell detonated under his horse. Horse and rider momentarily disappeared in an expanding blossom of smoke, flame, and bloody entrails. Maude’s mount was disemboweled by the shell, the animal an eviscerated heap of horseflesh. The captain himself was badly wounded, his arm almost severed, but a tourniquet staunched the blood that pumped onto his gold-braided uniform and he was taken to the rear.

Lord Lucan finally ordered what remained of I Troop to withdraw. They had given a good account of themselves for almost a half-hour, but their only source of ammunition—that which was stored in their limbers—was now exhausted. Captain Barker’s W Battery also went forward, but was also forced to withdraw under heavy fire.

Against all odds the “Turks” of Redoubt No. 1 had defended their post with courage and resolution. For an hour and a half—some sources say two hours—they withstood terrific punishment without flinching. But now the Russian artillery slackened, a clear signal that a Russian infantry assault was imminent.

Around 8 o’clock spike-helmeted columns of the Azovsky Infantry Regiment moved forward against Redoubt No. 1. They paused under heavy Turkish fire at the base of Canrobert’s Hill, their eyes trained on Colonel Kirdner. At his signal, they started climbing up the steep slope with a deep-throated “Ura!”, the Russian soldier’s traditional cry of exaltation. A Russian military axiom holds that “Pulya du ra, Stoik geroy” (Free translation: “The bullet is a fool, the bayonet is a hero”). Cold steel was going to be the order of the day.

The Azovsky Regiment breasted the earthworks and descended into the redoubt with the zeal of avenging furies. To the Russians these “Turks” were infidels, and the regiment had taken many casualties in its upward ascent. Over 170 Tunisians were killed, though some managed to escape by jumping over the ramparts on the other side.

The British Defense Line had Been Breached

It was all too much for the garrisons of Reboubts 2, 3, and 4, who quickly joined the survivors of No. 1 in precipitous flight. It became a general stampede, the Tunisians holding sacks of their worldly goods in one hand as they ran with rapidly scissoring legs.

For the Russians it was now time to implement the second part of the operation. Phase Two was going to be largely a cavalry affair, a reconnaissance in force. The British defense line was like a thin eggshell—the fall of the redoubts had just now cracked that shell, and the Russian cavalry was on hand to exploit the growing fissures. If the cavalry could take Kadikoi, for example, so much the better.

Lieutenant General I.I. Ryzhov of the 6th Hussar Cavalry Brigade was given the main responsibilities of the second phase of the battle. His command included the 11th Kievsky Hussars, the 12th Ingermanlandsky Hussars, and the 1st Ural Cossack Regiment. These horsemen were supported by the 3rd Don Cossack Battery and 12th Light Horse Battery.

In the meantime, Raglan positioned himself on the Sapoune Heights, the easternmost edge of the Chersonese Plateau. The view was breathtaking, with Balaklava Plain and its assorted ridges and valleys spreading before him like a three-dimensional map. But the jaw-dropping “bird’s-eye” aspects of the position had some serious flaws. First, it was far away from Raglan’s various commands, which meant it took mounted messengers 20 minutes or more to ride up and down the steep, shrub-dotted cliffs.

But even worse, Raglan’s perch some 600 feet above the plain was a little bit too Olympian and grand. He could see the battlefield with crystal clarity, not seeming to realize the same did not necessarily hold true for his commanders in the valley floors far below. Sight lines were different in the North and South Valleys—ridges and hills often obstructed enemy positions.

Meanwhile, the British cavalry was pulling back toward their camps to the west. This was logical, insofar as their original positions were untenable owing to heavy Russian artillery fire. But a dispatch from Lord Raglan muddied the waters at once. “Cavalry to take ground to the left of the second line of redoubts occupied by Turks,” read the missive, which was utterly incomprehensible to Lucan. To the left of what? What “second line of redoubts?” As far as anyone could see, there was only one line, the string of fortifications recently seized by the Russians.

When Raglan’s aide sorted it out, the position was found to be near where the South Valley begins sloping toward the Causeway Heights. It was 2,000 yards from Campbell’s position, and visibility was virtually nil.

Sir Colin Campbell watched the unfolding events with a mixture of resignation and firm resolve. The 93rd Highlanders were going to be the anchor of his defense, and he had every confidence in them. The regiment mustered some 550 men, big, brawny Celtic warriors eager to come to grips with the enemy. The Highlanders were supported by a hastily assembled assortment of soldiers from the Balaklava town, including a hundred “excused boots/light duties” men who had been ill.

There was also a Turkish brigade, and a “scratch” collection of redoubt fugitives that Campbell had taken in hand and whipped into something vaguely resembling a military formation. Captain Barker’s W Battery was on hand to provide artillery support.

The 93rd assembled on the hill just above Kadikoi in a two-deep line formation. The months of campaigning had taken their toll on their once-pristine uniforms, but they were still a magnificent sight in their brick-red coatees banded by broad white stripes. They wore the kilt, in the distinctive dark green “government set” pattern, which showed kneecaps and muscled legs, and their feet were covered in shoes and white “spats”-like gaiters.

Meanwhile, 400 Russian cavalry detached from the main body, their mission to make a reconnaissance of Balaklava’s inner defenses. These were the men of the Ingermanlandsky (or Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar’s) Hussars, sabers out and flashing in the morning sun, and as they closed with the Highlanders their advance gained momentum. At about 800 yards the Turks unleashed a volley then broke and fled.

“There is No Retreat From Here, Men”

Campbell was on hand, mounted on a horse and wearing a Highland bonnet. This was strictly nonregulation, and he had to apply for permission from Lord Raglan to discard the normal officer’s cocked hat. He was an inspiring presence, his face seamed from a lifetime of hard campaigning, white mustache above a firmly set mouth.

“There is no retreat from here, men,” he called out to his Highlanders, two long red ribbons set against an azure sky, “you must die where you stand.” Coming from any other man, these words would have sounded trite, even clichéd, but Colin Campbell meant every syllable. John Scott, the right-hand man of Lieutenant Burrough’s Company, replied in a broad Scots brogue, “Ay, Ay, Sir Colin; an needs be, we’ll do just that!”

The blue-coated Russian Hussars galloped ever closer, but Campbell refused to give the order to form square, which was the standard infantry defense against cavalry. “I knew the 93rd,” the general later remarked, “and did not think it was worth the trouble of forming a square.”

Events were soon to prove him right. The Highlanders unleashed a volley at 600 yards, bayoneted muzzles spitting gouts of smoke and flame, but the distance was too great to make an impression. Captain Barker’s W Battery chipped away at the mass of Russians, but the bulk of these horsemen rushed on toward the Highlanders.

At 150 yards officers ordered another volley. Highlanders pulled their triggers and musket butts slammed back into their red-coated shoulders. This time the effect was devastating. Horses crumpled, spilling riders into the dust. But the Highlanders were in line, not square, so their flanks were vulnerable. The Russian cavalry suddenly split in half, two currents of horseflesh that sought somehow to avoid the solid red wall. As some of the hussars swept to the left, it was obvious they were going to try to hit the 93rd in flank.

But a certain Captain Ross and his grenadier company detected these horsemen, wheeled about at an oblique angle to the main lines, then delivered a stinging volley that sent the Russians packing. Thoroughly chastened, the cavalry retreated back to the captured redoubts. The Highlanders had shown their mettle, successfully defending Kadikoi and Balaklava. But the Russians were not completely empty-handed—the 400 horsemen had gone forward to scout the inner defenses, a mission they had successfully accomplished, if at a cost.

Thin Red Line

London Times journalist William Russell saw the incident from Lord Raglan’s observation post on the Sapoune Heights. Overcome with emotion at the sheer spectacle, he ecstatically wrote of the “thin red streak tipped with steel.” Over time this was changed to the more pleasing “Thin Red Line.” Whatever the name, the 93rd’s brief but heroic stand at Balaklava became celebrated as an icon of Victorian military history.

About a half an hour earlier, Lord Raglan had swept the field with his telescope and suddenly realized that Campbell was truly out on a limb without support. The commander-in-chief also didn’t like the looks of the Turks that Campbell had recruited; even from a distance, they looked as if they were going to take to their heels at any moment.

Raglan quickly dictated another message to Lord Lucan, which ran as follows: “Eight squadrons of Heavy Dragoons to be detached towards Balaklava to support the Turks who are wavering.” Raglan was ordering the Heavy Brigade forward to support Campbell, that much was clear. But the Heavy Brigade had five regiments, each of two squadrons. Did Raglan want to keep one regiment in reserve? For what reason? Lucan was irritated, but followed orders to the letter. Four regiments of the Heavy Brigade moved out, but the fifth regiment, the Royals, stayed behind.

The Heavy Brigade consisted of some of the most famous cavalry regiments in the British Army, including the 2nd Royal North British Dragoons (Scots Greys), the 4th Royal Irish Dragoon Guards, the Fifth Dragoon Guards, the 6th Inniskilling Dragoons, and the Royals. Their commander was Brig. Gen. the Honorable James Scarlett, formerly of the 5th Dragoons. With his thick, white mustache, jowls, and a florid complexion that hinted at an inordinate love of the bottle, Scarlett looked like a typical English country squire.

The Heavy Brigade rode into the South Valley in the general direction of Kadikoi, the looming Causeway Heights on their left. They became somewhat strung out along the march, partly because of the terrain, which was dotted with deserted vineyards and patches of stunted scrub brush. The vineyards were particularly hazardous, with their crumbling walls, creeping vines, and hidden potholes.

Scarlett’s command was strung out over a half-mile in two columns, the 6th Inniskilling Dragoons in the lead, followed by the Scots Greys and the 5th Dragoon Guards. The 4th Royal Irish Dragoon Guards brought up the rear, while the Royals were not even in the picture—yet.

General Scarlett rode with a small staff group to the left of his columns. Looking up toward where Redoubt No. 5 crowned the Causeway Heights, Scarlett’s aide Lieutenant Alexander Elliot noticed that the ridge was “fretted with lances”—first indications that Cossack horsemen were approaching from the other side of Causeway Heights. Elliot touched Scarlett’s arm, pointing in the direction of the Cossacks, who by now had made an appearance on the crest of the ridge. The general was nearsighted—the horizon was just a blur of indistinct shapes and colors—but his reaction was anything but myopic.

“Left wheel into line,” Scarlett cried, the leading elements of the Heavy Brigade immediately obeying. At this juncture Lucan arrived at the scene, urging his white-whiskered subordinate to charge. He was preaching to the converted, because Scarlett was already in the midst of preparing for just such an attack.

“Scarlett’s 300” Vs. 1,600 Russians

As if to underscore his impatience, Lucan had a trumpeter sound the charge, but the clarion call fell on deaf ears. Officers of the Scots Greys and Inniskillings refused to be rushed, preferring to properly dress ranks before advancing against the Russian cavalry. Regimental sergeant majors aligned the red-coated ranks with parade-ground precision, as sabers rasped out of scabbards. All eyes were focused on General Scarlett, who ordered his own trumpeter to sound the charge.

Scarlett led the way, outdistancing the first line by at least 50 yards. Sword flashing in the sun, he turned around in the saddle and motioned to his troopers with an encouraging “Come on, Greys!” before spurring his horse forward. The first wave was composed of two squadrons of the Scots Greys and one squadron of the Inniskillings, later immortalized as “Scarlett’s 300.” They faced 1,600 Russians who were spilling over the lip of the ridge, a volcanic eruption of lance, steel, and horseflesh that threatened to engulf the British and sweep them away. The British were at a disadvantage since the rough, uphill nature of the ground slowed their charge to little more than a brisk trot.

Scarlett plowed into the Russians, saber swinging wildly at every target, giving and receiving blows with wild abandon. The general was wearing the brass “coal scuttle” helmet of his old regiment, the 5th Dragoon Guards, which might have contributed to his subsequent survival. The Russians mistook Lieutenant Elliot as the commanding officer, because he was an older man and was wearing a standard officer’s cocked hat.

A Russian officer came forward, intent on cutting Elliot down, but the lieutenant parried the blow and thrust his saber through the Russian’s body. The weapon went right through his unfortunate opponent, the blade impaling him to the hilt. When Elliot withdrew his sword, the once-shiny blade was crimson coated.

When the main body of “Scarlett’s 300” crashed into the Russian line, the impact was terrible. Fueled by adrenaline, saber-wielding red-coated arms rose and fell and rose again with an almost mechanical regularity, hacking a path through the Russian ranks. The 4th and 5th Dragoons joined in, hitting the Russian flanks, and the staggered nature of these British thrusts did much to weaken Slavic resistance.

On their own initiative the Royals soon joined the fight. Troop Sgt. Maj. Norris of the Royals was beset by four Russian hussars; he parried all blows, killed one assailant, and put the rest to flight.

Each British trooper was in his own world, his senses assaulted as much as his body. Ears were deafened by the sharp clang of metal on metal, the screams of wounded men and animals, and the curses and battle oaths of friend and foe alike. A captain in the Inniskillings recalled that it was “forward-dash-bang-clank; and there we were in the midst of such smoke, cheer, and clatter, as never before stunned a mortal’s ear—it was glorious!” Another officer, more laconic, remembered it as “rather hot work.” Hot work indeed, because the Russians wore thick, leather, spiked helmets and heavy gray greatcoats that deflected blows.

The Russians Eventually Gave Way, and Retreated

From Sapoune Ridge the Russian cavalry looked like an amorphous creature, a giant gray-black amoeba ready to absorb and digest the few red lines that dared approach it. The weather was fine, visability perfect, and observers could identify Scarlett and the others from afar. The British cavalry’s red coats stood out in high relief, and soon crimson rivulets were observed seeping even deeper into the seething Russian mass, splitting it into smaller pieces.

The Russians began to give way and were soon in full retreat. C Troop, Royal Horse Artillery also made a significant contribution, their 24-pounder howitzers raking the enemy “with admirable results.” Observers with Lord Raglan on Sapoune Heights broke into cheers, and some even threw their hats into the air in sheer joy.

Battle frenzy was soon replaced with a feeling of exhaustion, but the “Heavies” were also buoyed with the satisfaction of a job well done. Horses were blown, their flanks covered in foamy sweat. Sword arms ached, and uniforms were spattered with blood. But the Heavy Brigade had scored an amazing victory against the odds.

The Russian cavalry had retired, but Czarist forces were still masters of three of the Turkish redoubts. It was always possible that they would consolidate their holdings, the better to sweep down on Balaklava at a future time. But Lord Raglan was simply not prepared to accept this new state of affairs. The Heavy Brigade’s charge was magnificent, but there was no infantry to exploit the victory. So Raglan ordered the 1st and 4th (Infantry) Divisions to descend from the Chersonese Plateau to the plain below. This they began to do, but progress was slow.

Lieutenant General Sir George Cathcart’s 4th Division had been assigned a leading role in retaking the redoubts, but Cathcart, though moving, was dragging his feet. When the first alarm was sounded over the Russian attack, he initially refused to move. His men had spent an exhausting vigil in the trenches before Sevastopol, and for all he knew this might be a false alarm.

Raglan started to grow impatient—and issued a series of vague orders that cavalry commander Lord Lucan misunderstood, or perhaps misinterpreted. Eventually the Light Brigade was moved up to the head of the North Valley, while the reforming Heavy Brigade stayed around the South Valley. The Light Brigade dismounted and waited an hour and a half for further developments.

Up on his high perch on Sapoune Heights, Lord Raglan was anything but calm. The lead elements of the 1st Division were winding their way down into the plain, but it all seemed so glacially slow to the frustrated commander-in-chief. His cycle of woes seemed complete when a staff officer noticed that the Russians were active in the captured redoubts. “They’re going to take away the guns!” the officer cried, and a quick sighting through telescopes confirmed the assertion.

The Russians were bringing up artillery horse teams and lasso tackles, a clear indication that they were going to haul away the redoubt guns as prizes. A shock of horror swept though the observers on Sapoune Heights, because the captured guns could be used as talismans of a Balaklava victory. Raglan hurriedly dispatched an order to Lord Lucan, advising him to “advance rapidly to the front—follow the Enemy and try and prevent the enemy carrying away the guns.”

“We Call Lucan the Cautious Ass, and Lord Cardigan the Dangerous Ass”

The missive was given to a Captain Somerset J. Gough Calthorpe, the next aide-de-camp on duty, but Raglan told his Quartermaster General Richard Airey: “Send Nolan.”

Captain Louis Nolan of the 15th Hussars was selected because he was a superb horseman who could get down the treacherous plateau slopes quickly. But he was the wrong man for the job. He had a reputation as being hotheaded and impulsive, and as a man who burned for action. Moreover, he was infuriated by the Light Brigade’s relative inaction and jealous of the Heavy Brigade’s recent triumph. Impatient, touchy, contemptuous of his superiors, he once had written that “we call Lucan the cautious ass, and Lord Cardigan the dangerous ass; Lord Cardigan has as much brains as his boot.”

When Nolan delivered the order Lucan was puzzled. From his vantage point, he could not see the captured redoubt—in fact, he couldn’t see any Russian activity at all. The only Russian guns he could detect were over a mile away down the eastern end of North Valley. Lucan asked “Attack? Attack what? What guns?”

By now, Nolan’s simmering hatred for Lord Lucan brought his temper to a boil and he made a stinging, insolent reply. “There, my Lord, is your enemy; there are your guns,” Nolan said, his arm making a sweeping gesture not toward the Causeway Heights and the redoubts, but to the Russian guns at the end of the valley.

If true, the order was suicidal. The Light Brigade would be exposed to cannon and rifle fire on three sides, but Nolan refused to elaborate further. Lucan rode up to Maj. Gen. Lord Cardigan, commander-in-chief of the Light Brigade, to personally convey what he thought were Raglan’s express orders. James Thomas Brudenell, seventh Earl of Cardigan, was a martinet whose volcanic temper made him unpopular among his officers. He was an unimaginative, rather stupid man, though not the incompetent fool of Crimea legend. The Light Brigade commander calmly accepted the news, but pointed out that “the Russians have a battery in our front, and batteries and riflemen on each flank.”

“I know it,” Lucan replied, “but Lord Raglan will have it. We have no choice but obey.” Those simple words sealed the fate of the 673-man Light Brigade. Five regiments comprised the Light Brigade: the 17th Lancers, the 8th and 11th Hussars, and the 13th and 4th Light Dragoons. Their horses were in poor condition, in part due to a rough passage from England, but the brigade was in fine fettle and eager to show they could do as well—or better—than the “Heavies.”

They were fiercely determined to do their duty, but the men’s enthusiasm must have cooled when they realized the very immensity of the task that lay ahead. The main objective was the four 6-pounder guns and four 9-pounder howitzers of the No. 3 Don Cossack Battery, about 11/2 miles down the valley from their position. The battery was supported by swarms of Russian cavalry, including the Ural Cossacks and units of the Ingermanlandsky Hussars—the same regiment that had been sent packing by the Highlanders a couple of hours before.

But that wasn’t the half of it. The Light Brigade would be subjected to artillery fire from the Causeway Heights area on the right and the Fedioukine Heights on the left. A frontal attack on a battery was risky enough, but a charge while subjected to simultaneous artillery fire on three sides was suicidal.

Nolan’s Dying Shriek Chilled the Blood of All Who Heard It

A grim-faced Lord Cardigan rode off to Lord George Paget, his second-in-command, telling him, “You will take command of the second line, and I expect your best support, mind, your best support.” Irritated at what he perceived as Cardigan’s “schoolmaster” tone, Paget quickly voiced his assent, all the while smoking a cigar.

Initially, the first line was meant to consist of the 11th Hussars on the right, 17th Lancers in the center, and the 13th Dragoons on their left. Then, to narrow the overall frontage Lord Lucan pulled the 11th Hussars out of the first line and placed them in a second, or support, line along with the 4th Light Dragoons and 8th Hussars. The support line would be led by Lord Paget, still clenching a cigar in his teeth.

Lord Cardigan took his place at the head of the formation and ordered: “The Brigade will advance!” in his loud, hoarse voice. Turning to Trumpeter Billy Britten of the 17th Lancers, Cardigan said, “Sound the Advance,” which was immediately obeyed. After a few moments Britten sounded the “trot,” his brassy notes echoing over the sounds of jingling harnesses and snorting horses. These were standard cavalry tactics, where the pace was quickened in an orderly, step-by-step fashion. Technically, the actual charge, a flat-out, hell-for-leather rush into enemy positions, would start when the formations were about 100 yards from their objective.

As the brigade moved off, Captain Nolan rushed forward until he was on the same level as Cardigan. Ever a stickler for the rules, Cardigan was angered by the apparent breech of military etiquette. According to some accounts, Nolan seemed to be gesturing—did he finally realize the Light Brigade was going the wrong way and attacking the wrong objective? His motives will never be known, because at that instant one of the first Russian shells exploded and a fragment tore open his chest. Nolan’s dying shriek chilled the blood of all who heard it—a banshee howl for the terror and horror to come.

Russian gunners on the Fedioukine Heights must have felt that the Light Brigade was soon going to wheel right and advance on the captured redoubts. Such a maneuver would take them out of effective range, so they had to act fast while the British horsemen were still crossing their front. The No. 1 Position Battery, 16th Artillery Brigade, was ensconced on the Fedioukine Heights with a complement of six 12-pounder guns and four 18-pounder howitzers. The sweating Russian gunners worked with a will, firing, swabbing, and loading their guns as quickly as possible, taking care between shots to traverse their pieces as their targets moved.

A Trial by Fire for the Light Brigade

Colonel A.P. Skiuderi’s troops in the Causeway Heights were sure that the Light Brigade was going to turn in their direction at any moment. It was logical to assume the British were going to make some attempt to retake the redoubts, so the Odessky Jaeger Regiment formed four battalion squares. It was the standard formation to receive enemy cavalry. But Russian jaws dropped when the enemy horsemen moved past them and continued down the North Valley. What were these Angliski (English) up to?

Captain Bojanov’s six 6-pounder guns and two 9-pounder howitzers of the No. 7 Light Battery were newly sited along the northern edge of the Causeway Heights, and they soon sprang into action. The Light Brigade’s trial by fire had begun in earnest. The once placid valley was transformed into an arena of death more terrible than the Roman Coliseum. Flames and smoke stabbed from cannon muzzles with clockwork regularity, the succession of booming reports merging to produce a deafening cacophony.

Trumpeter Britten was severely wounded shortly after sounding “trot,” and so could no longer issue the stepped increases in speed. Likely, not many troopers would have heard his brassy notes in any case because of the noise of the cannon. Thus all cadence went by the board and the Light Brigade made forward as best it could amid the artillery fire.

A hail of roundshot peppered the ranks, complemented by flame-streaked white blossoms of exploding howitzer shells. Sergeant Major Loy Smith of the 11th Hussars recalled that his troop was decimated, noting “Private Turner’s arm was struck off close to the shoulder and Private Ward was struck full in the chest.” Whole clusters of horsemen tumbled to the ground in bloody ruin, but the survivors pressed on. As bloody gaps appeared in the lines, officers shouted, “Close in! Close in to the center!” above the din in an effort to maintain some sort of order.

Originally the Heavy Brigade was supposed to support the Light Brigade, but when a distraught Raglan saw what was happening he issued an immediate halt order.

Troopers were blown from the saddle, leaving their fear-crazed mounts without direction. Nostrils flaring, eyes bulging in terror, these trained cavalry horses instinctively sought comfort and guidance from surviving troopers. Lord Paget remembered that he had “at one time as many as five on my right and two on my left, cringing on me, and positively squeezing me as the round shot came bounding by them … my overalls being a mass of blood from their gory flanks.”

Only 37 of the 145 17th Lancers Remained

Closer they came to the head of the valley. Shot and shell intensified, tearing, lacerating, and eviscerating with horrifying ease. Sergeant Talbot of the 17th Lancers had his head taken off by a cannonball, yet for about 30 yards the decapitated corpse rode on, lance still couched under his arm. The sergeant’s heart still pumped, sending twin geysers of arterial blood flowing from the severed neck. The corpse finally—and mercifully—rolled from the saddle.

Closer, closer they came to the Russian guns at the end of the valley. Then Lord Cardigan reached them and passed through unscathed, followed by what remained of the first line. But the first line was terribly decimated—the 17th Lancers alone had only about 37 men left of the original 145 who began the charge.

Captain William Morris and 20 survivors of the 17th managed to outflank the battery on the left and push on beyond it. Although thick clouds of white smoke scudded across the field, they could see large masses of Russian cavalry just ahead. “Now remember, what I told you, men, and keep together,” Morris remarked, turning in the saddle to address the troopers.

The Russians seemed unnerved by the mad, reckless charge they had just witnessed, so much so that they gave way before the tiny knot of British lancers. Morris pushed his mount “Old Trumpeter” into a gait and headed for a Russian officer, sword at point. The British captain’s weapon deflected his opponent’s guard and lanced into his body. The sheer momentum of the action thrust the blade completely through the Russian, the bloodied blade emerging out his back.

The impact almost unhorsed Morris, who found he could not withdraw the blade. Because his hand was bound to the guard, he found he was helpless against the swarm of Russians that began hacking at him. Morris was left badly wounded, his skull bleeding from two large saber cuts. Briefly captured, he escaped and somehow managed to make his way up the valley, finally collapsing unconscious near the body of his friend, Captain Nolan. Morris survived the action.

The audacious little band of lancers had run into a wall of Cossacks, forcing their retreat. Nevertheless, all seemed lost. Then the lancers heard a voice coming to them from a distance, crying “Seventeenth! Seventeenth! This way! This way!” It was Lt. Col. (and Brigade Major) George Wynell Mayow, and they thankfully rallied on him. Mayow took what remained of the 17th and the 13th Light Dragoons—about 12 men remained of that regiment—and they cut their way through to British lines.

About this time the support line reached the 3rd Don Battery, where they did fearful execution on the Russian gunners. Some of the artillerymen fought, only to be quickly dispatched, while others dived for cover beneath the scorching-hot barrels of their cannon. The cavalrymen had seen their comrades perish in droves and were not in the mood for mercy.

Colonel John Douglas of the 11th Hussars managed to outflank the Don Battery on the north side, then pitched into a large formation of Russian Ulans (lancers), scattering the lot. The 11th Hussars plunged deep into the Russian lines, pursuing several fleeing regiments of Cossacks and hussars with wild “fox hunt” abandon.

“We are in a Desperate Scrape! What the Devil Shall We Do?”

Eventually the 11th Hussars had to retreat in the face of a vastly superior enemy. The 11th ran into Lord George Paget and his 4th Light Dragoons, just coming up from the 3rd Don Battery. The combined remnants of the 11th Hussars and the 4th Light Dragoons totaled around 70 men. “They are attacking us, my lord, in our rear,” a trooper cried out to Paget. The tiny island of horsemen was completely cut off, lost on a milling sea of Russian cavalry—General Liprandi had ordered Colonel Jerobkine’s Ulans, including the Siberian Lancer Regiment No. 12, to block all escape.

“We are in a desperate scrape! What the devil shall we do? Where is Lord Cardigan?” Lord Paget asked a nearby officer. Paget grasped his bloody sword and ordered an advance; it was a forlorn hope, but the only other alternative was an unthinkable surrender. The British spurred their tired mounts forward, half-expecting they would never escape. But once again, the lancers gave way and let them through with just a few half-hearted stabs.

Returning Light Brigade survivors would still have had to run a gauntlet of fire, but for the brilliant and timely charge by the 4th Regiment of the French Chasseurs d’Afrique. The French cavalry galloped over rough ground by the Fedioukine Hills, silencing the Russian guns there. Some shots still came from the Causeway Heights, but at least there was no crossfire.

The French cavalry was the last act. To all intents and purposes the Battle of Balaklava was over. The Russians still possessed some of the redoubts, but little else. Balaklava was secure, but the knowledge was of little comfort to the shattered remains of a once proud Light Brigade. Of the original 673 men, only 195 reported for duty at first muster.

Most of North Valley was covered with the tragic detritus of war. Horribly wounded men and animals lay scattered about, staining the ground with their blood. Mutilated horses tried to rise, only to fall back on shattered limbs, while other mounts flailed the air in their death agonies. Troopers hobbled back to the British lines, some so terribly wounded they were more dead than alive. After a truce was declared the wounded were collected and cared for. Ferriers roamed the field, putting wounded horses out of their misery with well-placed pistol shots.

Lord Cardigan had ridden back from the Russian batteries almost as soon as he entered them, feeling it was not “a general’s duty to fight the enemy among private soldiers.” The thought that he still might be responsible for his men, or that he should rally them or provide leadership in a tight spot, never entered his empty head.

The Bloody Battle of Balaklava’s End

The Light Brigade was shattered, but authorities do not agree on the casualty figures. Of the 673 men who charged, 110 were killed, including at least seven who later died of wounds. Some 130 were wounded, and around 58 were taken prisoner. This amounts to a casualty figure of about 45 percent. Somewhere between 300 and 500 horses were lost, or had to be put down. The Charge of the Light Brigade proper lasted perhaps seven or eight minutes.

By this time, the infantry had come down from the plateau, but Raglan then decided that no further action would be taken to recapture Redoubts 1, 2, and 3. They would remain in Russian hands. Over the past 40 years much ink has been spilled over the fact that the Russian possession of the redoubts “cut off” the vital Woronzoff Road supply route. Much of the British Army’s subsequent hardships during the winter of 1854-1855 have been attributed to this, because supposedly without the Woronzoff Road, supplies could not reach the cold and hungry troops.

In reality the Woronzoff Road was not “cut off” or “lost” in any way, nor did the capture of two or three redoubts make the road untenable. Redoubt No. 3, the nearest captured one, is perhaps two miles from where the Woronzoff snakes up to the British camps.

In any event, the Battle of Balaklava was over, but the Crimean War went on. There were more battles ahead, and more hardships for long-suffering British troops. Sevastopol finally fell in 1855, and the Russian government sued for peace in 1856. Sevastopol’s dry docks were destroyed by allied engineers, neutralizing the Russian naval threat to the Mediterranean. Czarist ambitions in the Mediterranean and the Balkans were thwarted for another 20 years.

The bungling and mismanagement of the war was widely reported by such pioneering war correspondents as William Russell, and their stories raised a public outcry. The scandal led to slow—but steady—military reform. Thus the Crimean War, that blend of heroism and horror, bore some positive results after all.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments