By Peter Suciu

For the brave soldiers of Easy Company, it must have seemed as though World War II would never end. And actually it never did, at least not for the hard-fighting GIs led by Sgt. Frank Rock. From 1959 through 1988, Sgt. Rock and his men fought their way across France, battling Hitler and his evil minions. Today, the good sergeant and his fellow comic-book warriors are making a spirited comeback with discerning collectors.

The history of comics goes back more than 100 years. Today, the different eras are broken down by certain genres and characters. The earliest era of true “comic books,” known by collectors as the Platinum Age, lasted roughly from 1897 until 1937. While comic strips were popular in newspapers in the years prior to the Platinum Age, there were few actual comic books on the newsstands.

The Platinum Age of comics saw the introduction of humorous, satire-filled “funny books” and later the arrival of detective and science-fiction-themed comics. This led in turn to the era most associated in the popular mind with comic-book characters, the Golden Age (1938-1955). During this period, many of the enduringly popular superheroes, including Superman and Batman, arrived on the scene. When the United States entered World War II, these new heroes, along with Captain America and Wonder Woman, patriotically joined the fight. Wartime comic books featured the superheroes battling the Nazis openly and on covert missions behind enemy lines.

The Platinum Age of comics saw the introduction of humorous, satire-filled “funny books” and later the arrival of detective and science-fiction-themed comics. This led in turn to the era most associated in the popular mind with comic-book characters, the Golden Age (1938-1955). During this period, many of the enduringly popular superheroes, including Superman and Batman, arrived on the scene. When the United States entered World War II, these new heroes, along with Captain America and Wonder Woman, patriotically joined the fight. Wartime comic books featured the superheroes battling the Nazis openly and on covert missions behind enemy lines.

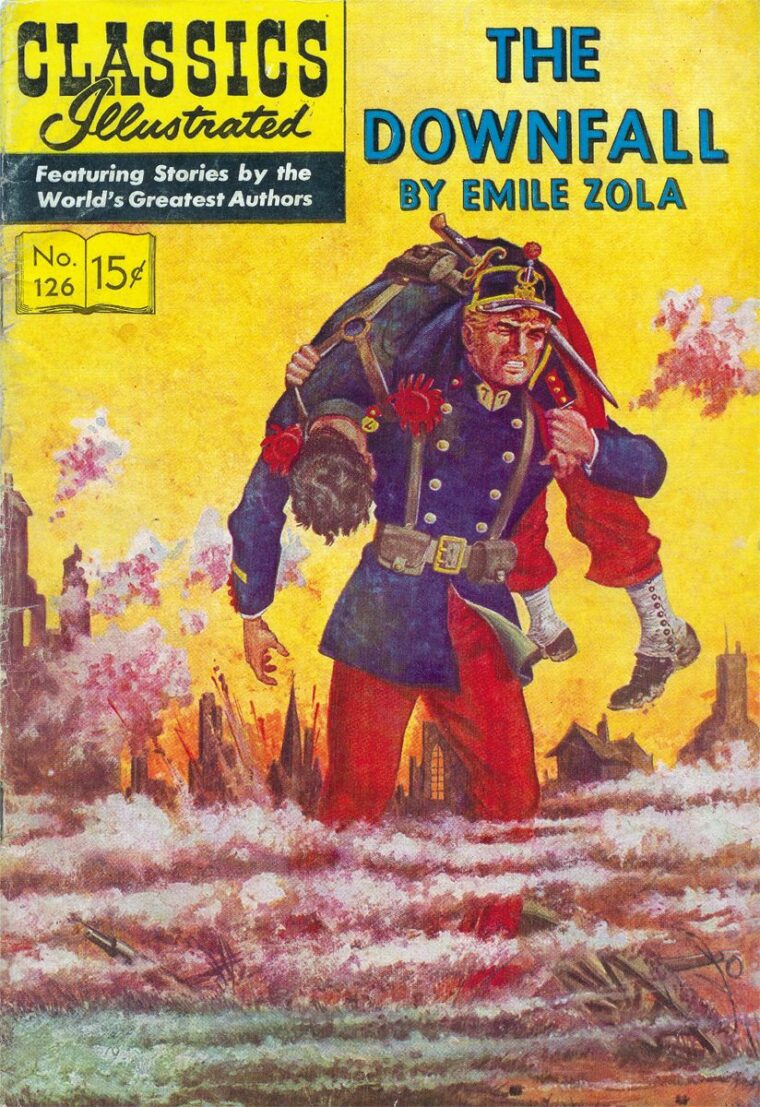

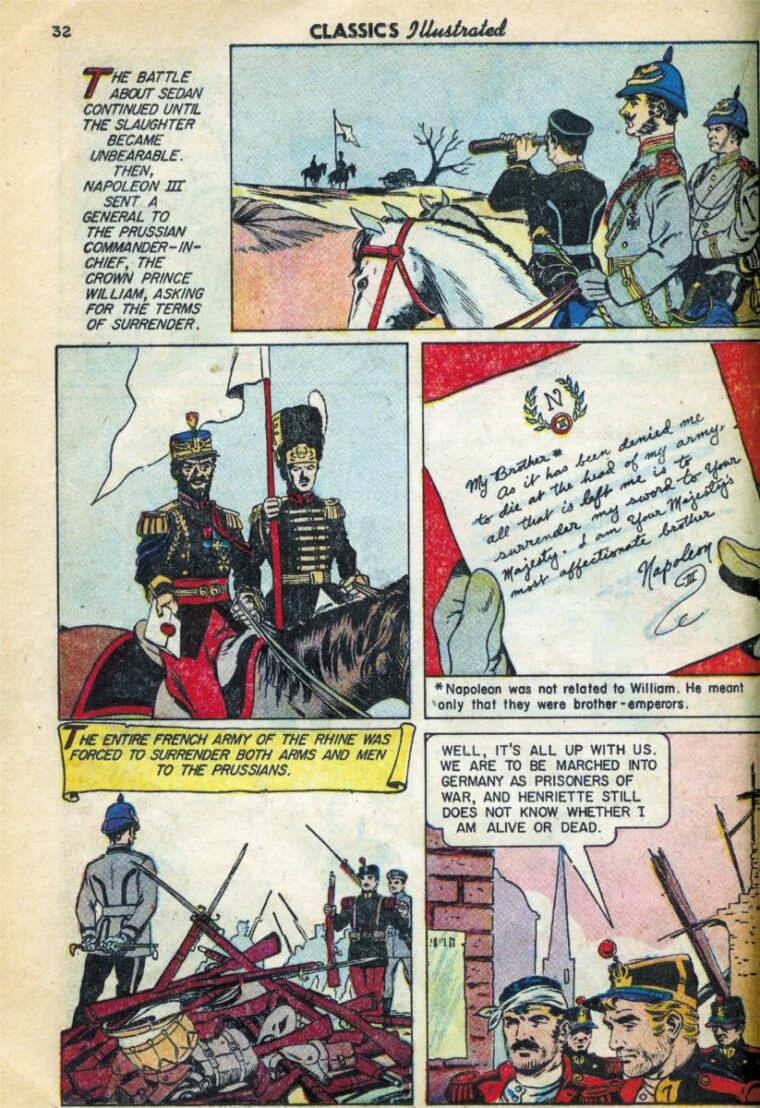

The Golden Age also saw the arrival of what is perhaps the first true war comic: Classics Illustrated. Based on adaptations from classic literature, the series of comics was introduced by Albert Lewis Kanter in 1941 for Elliot Publishing as Classic Comics. The original title was a 64-page adaptation of Alexandre Dumas’s The Three Musketeers. After three issues, Kanter started Gilberton Publications, and in 1947 he changed the title to Classics Illustrated. The high-quality comic book, which unlike many other titles of the day actually kept old issues in print, ran a total of 169 issues through 1962. While not all the titles were obviously war-related, Classics Illustrated introduced many young readers to such war classics as All Quiet on the Western Front, The Downfall, and The Red Badge of Courage. Over the years, the Classics Illustrated title switched hands, and various reprints have reappeared, but to a generation of schoolboys (and girls) growing up in the 1950s and 1960s, Classics Illustrated was an open window on great literature.

The birth of the true war comic can be traced to publisher Bill Gaines, who would later go on to launch the immortal Mad Magazine. Gaines’s father, Max, had been an editor at All-American Comics, which merged with DC Comics in 1944. Max went on to found Educational Comics, or EC, originally with the idea of releasing comics based on history, the Bible, and science. When Max died in 1947, Bill took the reins of the company, which changed its name from Educational to Entertaining Comics, but was still known in the trade as EC. Titles included crime fiction, science fiction, and horror, which soon attracted attention from parents’ groups and even led to congressional hearings. This eventually spawned the formation of the Comics Code Authority.

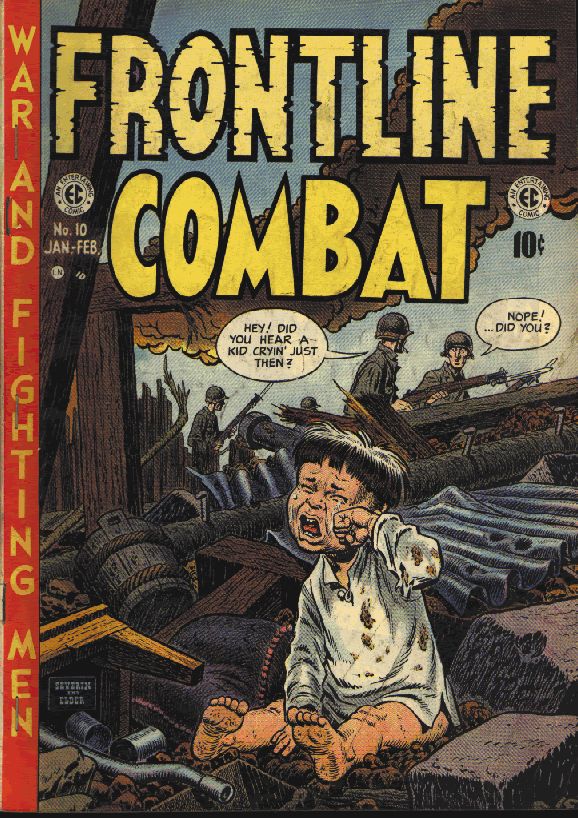

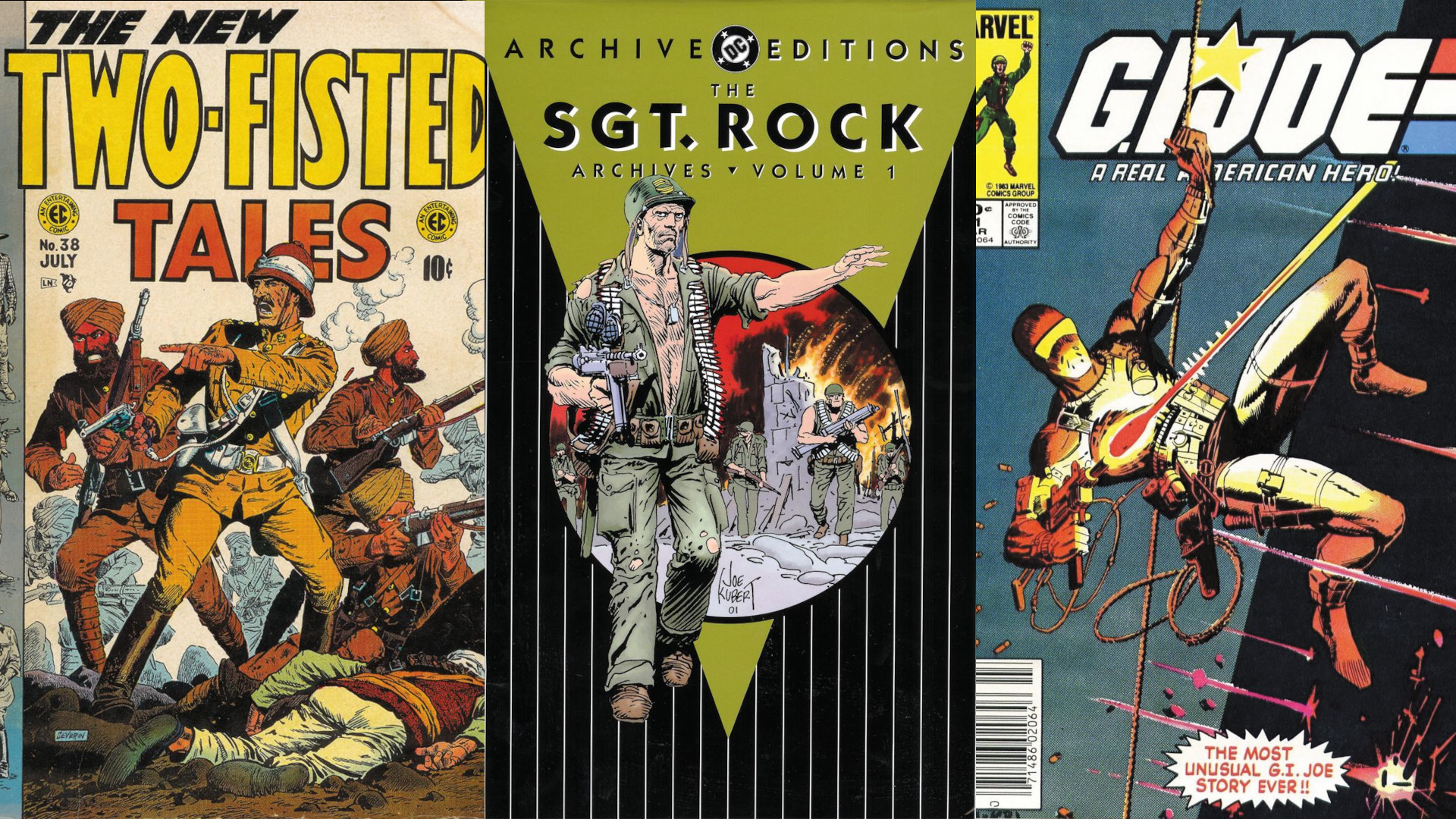

In the early 1950s, cartoonist Harvey Kurtzman suggested to Gaines that EC publish an adventure comic, and Two-Fisted Tales was born. The comic mixed Indiana Jones-style adventure stories with cowboys and Indians, as well as various military-themed accounts. The bimonthly comic was published with a companion comic called Frontline Combat, which focused on a variety of military actions—from the Napoleonic era to the then-current Korean War. It is worth noting that while Two-Fisted Tales began as a rousing adventure-oriented comic book, the war tales in both books were quite antiwar in tone, an unusual approach during the Cold War days.

“They were ahead of their time in several ways,” says Russ Cochran, publisher of EC Archives, which has rereleased many of the early EC comics in hardbound book form. “First and foremost, these comics did not glorify war and often spoke to the futility and human sacrifice involved in war. Kurtzman’s comics were concerned with human values and Kurtzman was a stickler for detail. When he did a story about men in uniform, he made sure the uniforms were correct, including the helmets. This degree of accuracy in historical detail is unique to EC.”

“They were ahead of their time in several ways,” says Russ Cochran, publisher of EC Archives, which has rereleased many of the early EC comics in hardbound book form. “First and foremost, these comics did not glorify war and often spoke to the futility and human sacrifice involved in war. Kurtzman’s comics were concerned with human values and Kurtzman was a stickler for detail. When he did a story about men in uniform, he made sure the uniforms were correct, including the helmets. This degree of accuracy in historical detail is unique to EC.”

Despite such attention to detail, neither magazine lasted long beyond its debut. Frontline Combat ran for 15 issues until it was dropped in 1954, when Two-Fisted Tales was changed from a bimonthly publication to a quarterly release. The comic ran a total of 24 issues, ending rather confusingly with issue No. 41. This came about because of the unique numbering system of comics in those days. Two-Fisted Tales had picked up the numbering of a horror comic named The Haunt of Fear, which in turn had picked up the numbering from The Gunfighter. No doubt many a collector has searched in vain for that elusive issue number one, only to learn that it doesn’t exist. But while neither of the comics lasted very long, they would serve as important springboards for artists who would return to the front lines with characters who would become household names for American youths a decade later.

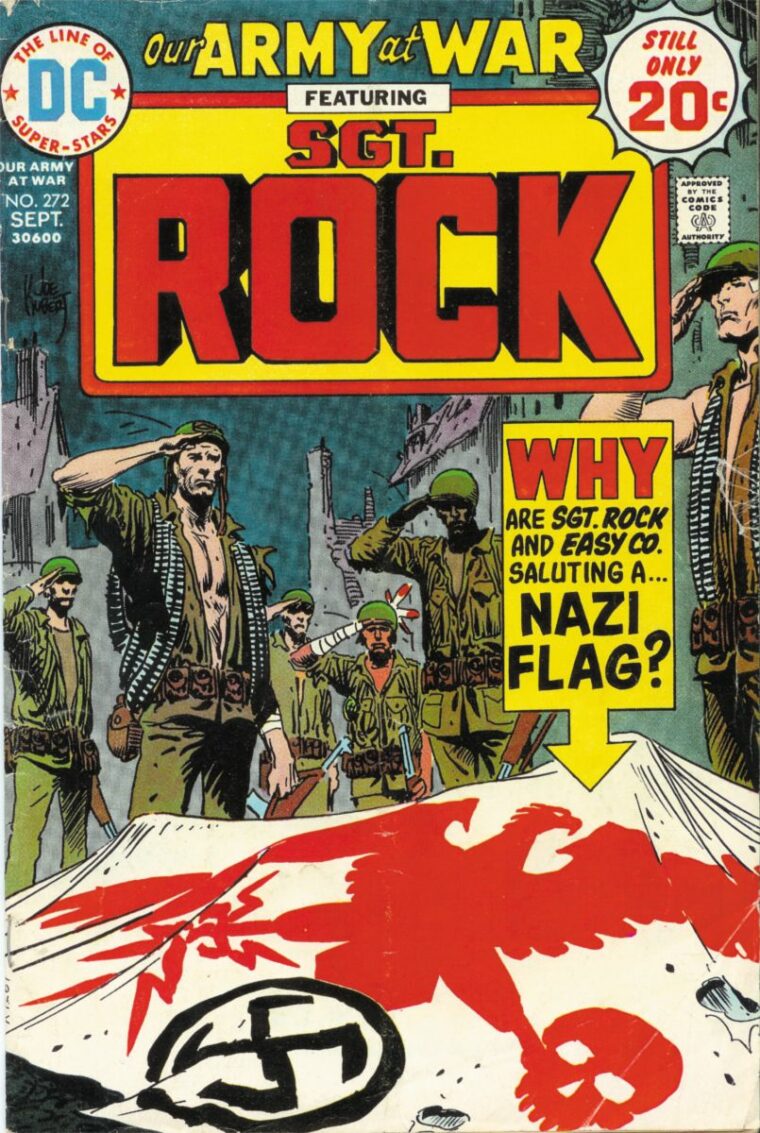

The best-known comic-book hero in the war genre reported for duty in 1959. His name was Sgt. Rock—his rarely used first name was Frank—and he first appeared simply as “The Rock” in issue No. 28 of the comic book, All American Men of War. The character returned in a story called “The Rock” in issue No. 68 of G.I. Combat in 1959. While originally not as popular as Two-Fisted Tales, G.I. Combat began to slowly develop a rabid following with its innovative anthology format of recurring characters.

Sgt. Rock proved such a hit that writer-editor Robert Kanigher and artist Joe Kubert fleshed out the character. He returned in issue No. 81 of Our Army at War in April 1959, and he would go on to become a signature character of the comic-book community for the next 30 years. In 1977 the name of the comic book was changed to Sgt. Rock, and it was published until issue No. 422 in July 1988. For Sgt. Rock and the boys of Easy Company, World War II lasted quite some time.

Through the Silver Age and the later Bronze Age of Comics, G.I Combat and Our Army at War were two of the most popular war titles. The books actually began as rivals until DC Comics, the home of Superman and Batman, merged with rival NCC. Throughout the Silver Age, which lasted until the end of the 1960s, the war comic was in its heyday. Other recurring characters and plots included The Haunted Tank, which involved a WWII Stuart tank that was protected by the ghost of General “Jeb” Stuart, and Johnny Cloud, a Navajo fighter pilot. While both were popular, they failed to capture the two-fisted spirit of Sgt. Rock.

For collectors of militaria today, it is easy to look back on the early comics as part of what sparked their initial interest in collecting. “I still have some of the comic books that I had when I was a child,” says North Carolina-based collector Bill Grist. “I am now 60 and they were at my parents’ house. I rediscovered them several years ago in a closet. And I would say that in my youth the comic books pertaining to World War II had a great effect on my lifelong hobby of collecting militaria, along with stories from my father and uncles, who served [in the war].”

For collectors of militaria today, it is easy to look back on the early comics as part of what sparked their initial interest in collecting. “I still have some of the comic books that I had when I was a child,” says North Carolina-based collector Bill Grist. “I am now 60 and they were at my parents’ house. I rediscovered them several years ago in a closet. And I would say that in my youth the comic books pertaining to World War II had a great effect on my lifelong hobby of collecting militaria, along with stories from my father and uncles, who served [in the war].”

Unlike the earlier works in Classics Illustrated or Frontline Comics, the tales in DC’s comics were far from historically accurate, did not follow actual events, and featured caricature villains. Today, many collectors laugh at the poor renderings of German uniforms with massive red swastikas on the side, but no doubt this artistic license made Sgt. Rock appear all the more heroic.

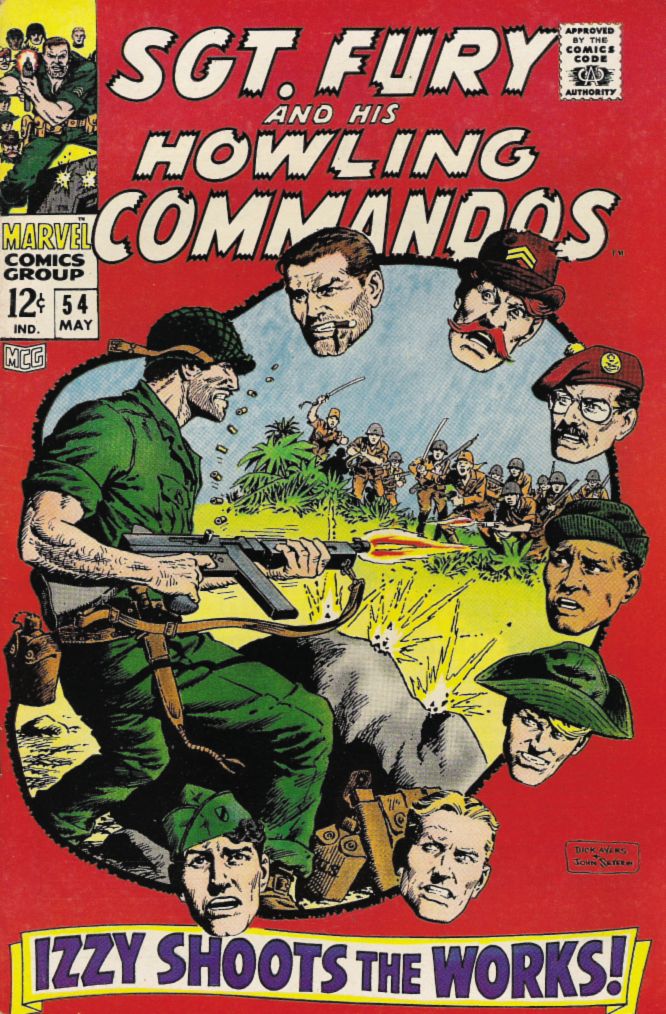

During the 1960s, even with an unpopular war taking place in Vietnam, the military-themed comics continued to be popular. And much like the jam-packed superhero arena, no one player would dominate the space. In 1963 another sergeant joined the fight against the Nazis—Sgt. Fury and his Howling Commandos. Published by Marvel Comics, which had begun in 1939 as Timely Comics, Sgt. Fury and his commandos were a bit more colorful and multinational than the men in Easy Company. Legendary artist-writer Stan Lee, who would later create the Fantastic Four, Spiderman, and the Hulk, was one of the creators behind Sgt. Fury.

Throughout the Silver Age of comics, the war theme would see the arrival of The Unknown Soldier and even enter the surreal world with Weird War Tales and Star Spangled War Stories. The Unknown Soldier was essentially the tale of a top-secret agent who was a master of disguise, and the stories were filled with as much science fiction as history. It was usually up to this nameless hero to stop the development of some nefarious Nazi secret weapon. Weird War Tales was the “Twilight Zone” of war comics, and usually featured a strange twist of fate, adding fantasy to the military setting. Today, Star Spangled War Stories is fondly remembered as “the dinosaur war book,” since it featured a recurring plot called “The War That Time Forgot” in which American soldiers found themselves battling dinosaurs and other monsters as often as they fought the Japanese.

Comic-book historians generally agree that 1970 was the year when there was a shift to darker themes, including the increased use of drugs and alcohol in many of the comics. It was also the twilight of the war comics, although many of the leading titles would continue until the middle of the 1980s. For such staple characters as Sgt. Rock and Sgt. Fury, the eternal struggle against the Nazis in Europe continued, but more momentous events were taking place behind the scenes. During the late 1970s, many of the veteran comic-book writers and artists began to retire, and a new generation of artists began to make names for themselves. This was evident in the style of art that emerged.

Much like the superhero comics, the war genre also took on a darker tone. This was most notable with the increasingly antiwar themes of the comics. The traditional heroes now were portrayed as antiheroes, and instead of patriotic themes, the comics stressed the overall futility of war. This was to be expected, as the United States was in the process of exiting the unpopular war in Vietnam. By the early 1980s, Sgt. Rock’s glory days were very much in the past.

Much like the superhero comics, the war genre also took on a darker tone. This was most notable with the increasingly antiwar themes of the comics. The traditional heroes now were portrayed as antiheroes, and instead of patriotic themes, the comics stressed the overall futility of war. This was to be expected, as the United States was in the process of exiting the unpopular war in Vietnam. By the early 1980s, Sgt. Rock’s glory days were very much in the past.

“The eventual ill fate of war comics was not from a lack of propaganda; it was from a lack of artistic grace and traditional idealism,” explains Robert Lynch of Gary Dolgoff Comics. A longtime reader of comics, Lynch notes the changes in artwork and stories. “Compare Joe Kubert’s brilliant Silver Age art in All American Men of War with his mostly mediocre art in Sgt. Rock from the late Bronze Age,” he says. “Whereas his earlier work was bold and creative, his later work was hardly frame-worthy.”

Lynch says that some artists stopped caring about the integrity of their work and focused more on the sheer volume of it. “Another reason for the death of war comics was due to a large change in our combined idealism,” he says. “War comics lean partly on the archetype of the independent man that we find in Western comics, and combine this with a band or small-group structure that we find in primates.”

By 1981, however, with the arrival of President Ronald Reagan in the White House, the nation’s mood began to change, and the view of the military improved accordingly. A new war comic emerged in the form of G.I. Joe. Based on the popular 12-inch action figure, the comic book was a relaunch for the toy line, one of the first toy-based comics and animated TV series that was directly related to a line of toy products. The first issue arrived in February 1982, and it ran until October 1994. At the same time, a line of Sgt. Rock action figures also appeared, in part to jump on the bandwagon of comic-based toys. And in 2002 a limited-edition 12-inch G.I. Joe version of Sgt. Rock was introduced, along with four of characters from Easy Company.

While the previous war comics focused on past conflicts, G.I. Joe was set in the modern day and relied on a James Bond-style battle between a secret special-ops force battling a sinister enemy bent on world destruction. Originally, G.I. Joe was to have faced a variety of enemies, with the “Joe Team” taking on various threats, including the equally powerful Soviet forces. But most important was their battle with the nefarious organization known as Cobra, which would become the staple enemy through the rest of the comic’s run.

By the end of the Bronze Age and arrival of the Modern Age of comics, it was apparent that the war genre was a relic of the past. Readership was down, and as a result the war that had lasted for decades on the pages of these comics finally came to an end. Sgt. Fury ended its run in March 1987, and Sgt. Rock’s final issue was a year later, in July 1988. The new theme of comics—or graphic novels as they were increasingly called—focused on superheroes once again. These weren’t the campy heroes of the Silver Age. A new crop of artists took pains to show such familiar heroes as Batman and Spiderman with recognizable human flaws.

This past year saw the welcome arrival of an original Sgt. Rock tale from Joe Kubert, entitled Sgt. Rock: The Prophecy. Following the larger graphic novel layout, the new book featured artwork superior to the Rock of the 1960s. If successful, it is possible that Easy Company could be back in business, returning to fight a new generation of evildoers.

This past year saw the welcome arrival of an original Sgt. Rock tale from Joe Kubert, entitled Sgt. Rock: The Prophecy. Following the larger graphic novel layout, the new book featured artwork superior to the Rock of the 1960s. If successful, it is possible that Easy Company could be back in business, returning to fight a new generation of evildoers.

Because of a new wave of nostalgia by baby boomers, the popularity of the old comics has picked up in recent years. For many militaria collectors, the comics of the Silver Age are most sought after, and the era of the big swastikas and sadistic Nazis are the best remembered today. Despite those flaws, or perhaps as much because of them, New Jersey militaria collector-dealer Kenneth Bolton says that it was there that his attraction to militaria was born. “It all began with war comics,” Bolton says. “Since I was a child in the 1960s and couldn’t afford to buy too much militaria, comics were the next best thing at 10-25 cents each. These depicted stories of heroes with great action flair and artistic scenes, which was a great appeal to preteens. War comics may still interest other militaria collectors, just because it reminds them of boyhood days. Now that we have grown to adulthood, we can afford the various militaria items that we always wanted.”

Likewise, the Bronze Age comics are also gaining in popularity with collectors, says Brian Cunningham, editor of Wizard, a monthly magazine devoted to comic collecting. “Nostalgia mania, especially 1980s material, is in vogue right now,” he notes. “With the war on terror and the situation in Iraq currently dominating headlines, war comics have become very popular and relevant again, both to old and new readers and collectors. Most of these titles ceased publication in the mid-1980s, and I don’t see it as a coincidence or a surprise that more war comics have been produced since these events began.”

Even if your mother tossed out those old comics years ago, there is still hope. Unlike the early Batman or Spiderman comics, which would require a second (and possibly third) mortgage on the house to buy, the early war comics are actually fairly affordable. Late Golden Age comics such as Two-Fisted Tales can be found online and from comics dealers for reasonable prices today, often below $100.

And even if you can’t find the original, there is a good chance of finding a long-remembered tale in one of the recent anthologies. EC Archives has begun to release compilations of its early titles, while DC has rolled out multiple volumes of The Haunted Tank and Sgt. Rock. They may not be the originals, but they are the next best thing to a stack of old comics—a surefire invitation to vicarious time traveling back to your youth.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments