By Peter Harrington

War produces casualties … and captives. Much “war art” concerns itself with the heroics and clash of battle, the sway of forces, and the turns of history. Little depicts the despair and degradation of prisoners. Nevertheless, these are haunting and instructive.

In some cases, POW images create an artificial view of life as a prisoner. Others capture the true horror of captivity. We see the relative comfort of Crimean War Russian prisoners, and also the harsh conditions of Union prisoners in Andersonville. From the relative tranquility of a game of baseball at Salisbury Camp, NC, to the brutal execution of Indians in the Mutiny of 1857, POW art presents the full range of the war captive experience.

Images of prisoners captured in wartime appear as far back as ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia; they are on bas-reliefs carved to commemorate kings and leaders. Trajan’s Column in Rome portrays prisoners captured during the Dacian wars.

The Napoleonic wars created vast numbers of captured soldiers. German artist Johann Michael Volz portrayed some of them in aquatints. Volz was an eyewitness to the forced march of Russian prisoners captured by the French after the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805. Several months later, he recorded some of the 30,000 Austrian prisoners captured at Ulm.

After the end of the Napoleonic wars, French artist Nicholas-Toussaint Charlet created a pair of prisoner lithographs. In the first, entitled Défile de Prisonniers Autrichiens, the artist shows a French soldier with a captured flag leading Austrian captives to the rear while other French troops advance to battle. In Deux Prisonniers Russes, two French soldiers escort two Russian prisoners.

Suspected Mutineers Were Hung or Attached to Cannons and Blown Apart

Russian POWs were the subject again of pictures half a century later, when the first captured soldiers arrived in Britain during the early months of the Crimean War. English artist Alfred Crowquill recorded a scene at the southern English town of Lewes where Russian prisoners were housed. In a moving scene, a little English girl is giving a gift to a prisoner. While en route to Scotland, French painter Denis-Auguste-Marie Raffet depicted other Russians—captured in the Baltic—imprisoned at Sheerness in southeast England.

Less fortunate were captured mutineers taken in India during the rebellion against the British in 1857-1858. The British retaliated for atrocities committed against European civilians. Suspected mutineers were either summarily hung or fastened to the mouths of cannon and literally blown apart, as shown in an image by the Victorian artist Orlando Norie.

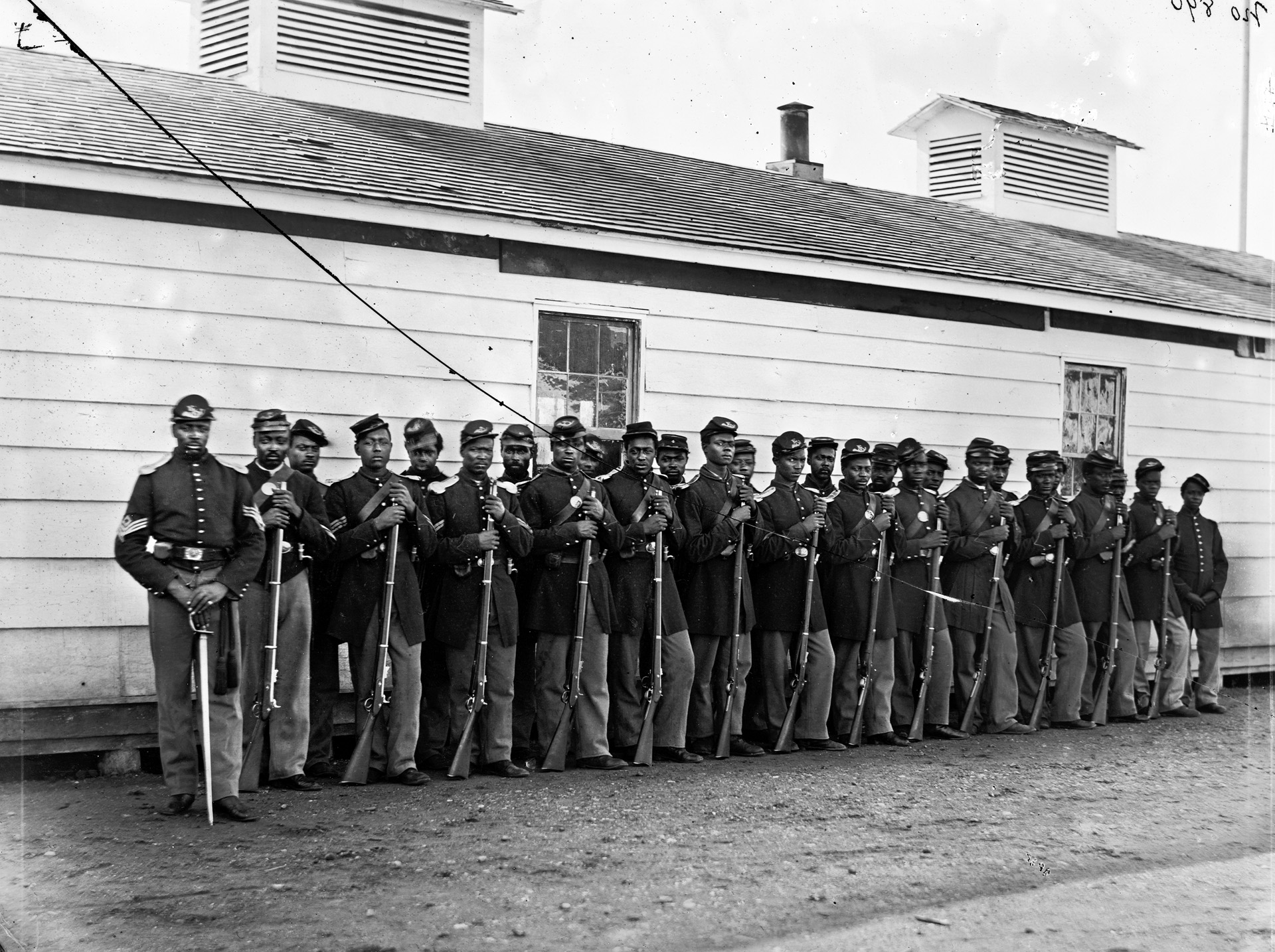

Less than a decade after the war in the Crimea and Baltic, the American Civil War produced many stories of prisoners of war. Otto Boetticher, a Prussian-born Union soldier who served with the 68th New York Volunteers, recorded scenes at two prison camps following his capture by the Confederates. He was incarcerated in various prison camps including Salisbury in North Carolina and Libby Prison in Richmond. His portrayal of a game of baseball at Salisbury Camp in 1864 is one of the first recorded images of the sport.

The conditions depicted by Boetticher suggest moderate comfort and civility. This stands in stark contrast to the situation at Andersonville, which was captured in a graphic painting by Al. Jer Klapp in 1884. Of all the prison camps of the American Civil War, Andersonville was the most notorious. Union prisoners were brutalized and lived in deplorable conditions with barely any shelter from the heat and humidity. Disease and starvation were rife and many hundreds succumbed. At the end of the war, the camp commandant, Captain Henri Wirz, was tried and executed for crimes against the prisoners. In Klapp’s picture, a guard has just shot a prisoner for crossing the Dead Line.

Many POWs Died From Disease and Poor Conditions

After 1865, the U.S. Army turned to pacifying the West. The destruction of the Native American tribes there was a dark period in American history, and thousands were killed or forcibly transferred to reservations. Old Fort San Marcos in St. Augustine, Fla., was turned into a prison for captured Plains Indians. Renamed Fort Marion, it housed 72 Southern Plains warriors and chiefs, including Chief Killer. He had fought during the late pre-reservation years and was a POW from the spring of 1875 until his release in April 1878. Given a sketchbook by his jailers, he created 15 original drawings of his life as a warrior as well as scenes of his prison.

The subject of POWs was a sensitive issue during the war in South Africa between the British and the Boers in 1899-1902. Both sides in the conflict respected prisoners’ rights, but in the latter stages of the campaign the British rounded up men, women, and children and placed them in “concentration camps,” where many died from disease and poor sanitary conditions. The concentration camp effort was an attempt to force the Boer guerrillas into surrendering, but it had quite the opposite effect.

In a scene drawn for Collier’s Weekly in 1900 by Swedish-American illustrator Thure de Thulstrup, soldiers of the Royal Irish Fusiliers captured near Ladysmith are being marched into Pretoria. The most famous British POW of the war was Winston Churchill, who was acting as a war correspondent. He later escaped from the camp.

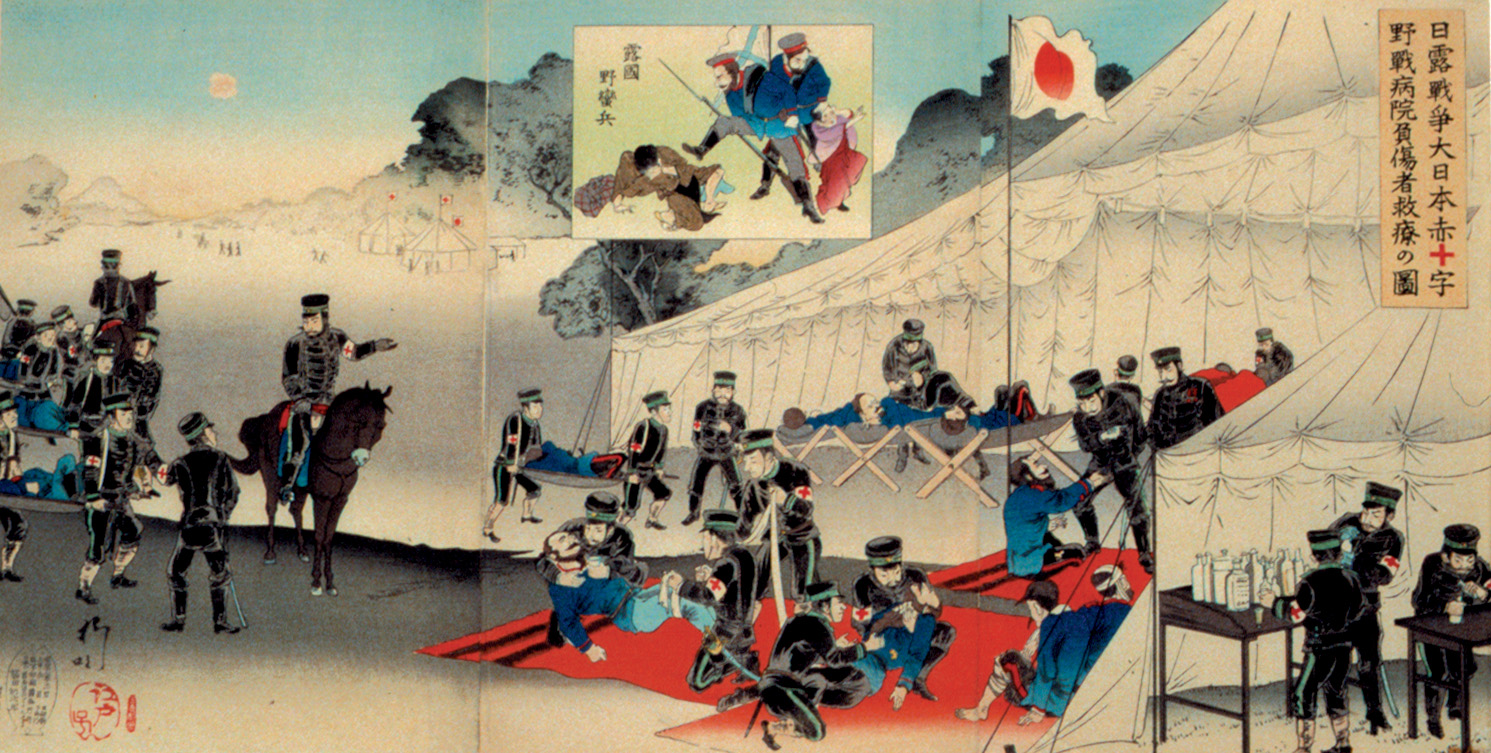

An interesting use of POWs for propaganda purposes appears in a colored woodblock print published in Tokyo in March 1904. Artist Ryüa (Takeuchi Kokunimasa) depicted a Japanese Red Cross field hospital during the Russo-Japanese War. The picture was designed to give the impression of Japanese humanity compared with Russian aggression. The Japanese hospital staff is giving medical assistance to captured and wounded Russians, while an inset shows Russian brutality against Korean civilians.

Although tens of thousands of soldiers became prisoners in the Great War, accounts of their experiences are not as extensive as are those from World War II. In fact, only the German prison camp at Rehldbren attracted anything approaching notoriety. Few pictures exist of captured soldiers, but the well-known British soldier-caricaturist Bruce Bairnsfather portrayed one group of captured Germans in a wash drawing entitled WHY M.C.A.? Bairnsfather was best known for his comical scenes of British soldiers during the Great War, in particular his “Ole Bill” series. In this picture, the artist has depicted five German prisoners lounging before a hut.

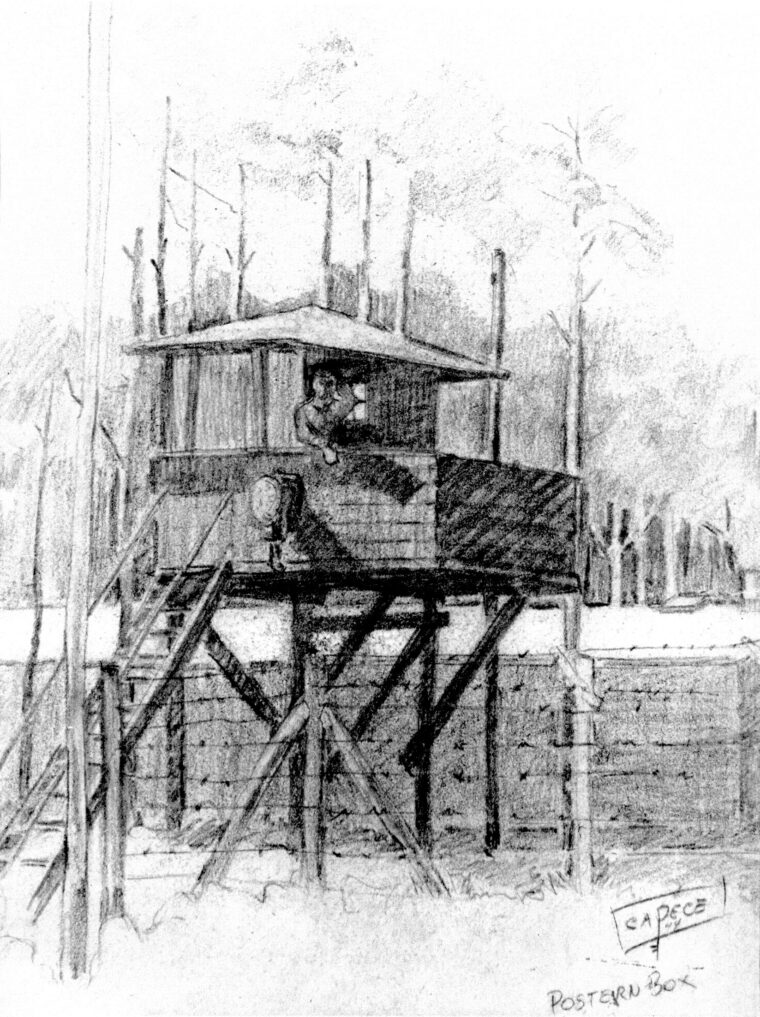

By contrast, World War II abounds with accounts of POW stories. Firsthand sketches are not so common, understandable considering the conditions many POWs had to endure and the difficulty in procuring art materials. One artist who managed to overcome these difficulties was William Capece. Serving with the U.S. Army Air Force, Capece’s B-17 was shot down over Germany on June 13, 1944. He bailed out at 20,000 feet and had to claw open his chute. He landed in a forest, injuring his knee. Luftwaffe officers drove him to Ingolstat Hospital where he met two of his crewmen. At Nuremburg station he was protected from angry Germans by his guards. Interned in Stalag Luft III in 1944, Capece drew many scenes of life in the camp. His effort to get drawing materials was unique; he drew “saucy” pictures of ladies for the German camp guards.

“It was a Nightmare to See and Read the Faces of These Men”

In the same month, the official war artist Manual Bromberg observed the temporary burial of American soldiers killed on Omaha Beach during the Normandy invasion. In this case, captured German prisoners were forced to act as pallbearers.

Conditions for German, Japanese, and Italian soldiers captured by the Allies were considered remarkably civil. Unfortunately, the case could not always be made for Allied POWs who fell into Axis hands, particularly those captured by the Japanese. Marine Corps artist Harry Reeks made a series of drawings of former Marine POWs on a ship he boarded at Honolulu in September 1945 bound for the United States. “It was a nightmare to see and read the faces of these men,” said Reeks. Earlier, Reeks had spent several weeks on Iwo Jima in February and March 1945 covering the campaign for the Marine Corps public relations department. One of his sketches depicted one of the few Japanese soldiers to surrender on the island, the rest choosing death over capture.

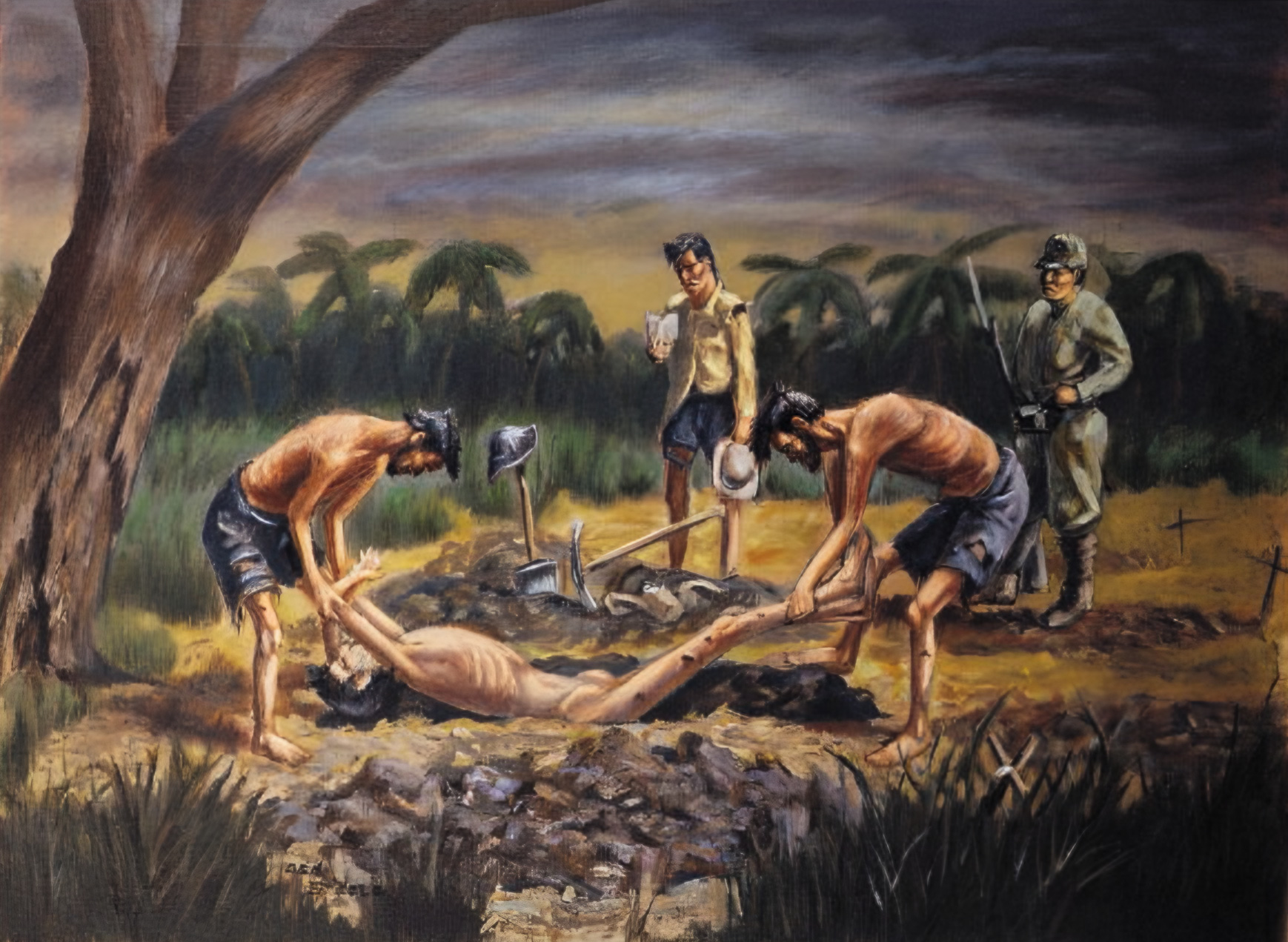

An American captive of the Japanese was Ben Steele. Enlisted in the Army Air Corps at Fort Missoula in 1940, Steele was at Clark Field, Philippines, in December 1941. He was captured on Bataan in April 1942 and forced into the Bataan “Death March.” Following internment in several camps, he was shipped to Japan where he was forced to work in a coal mine until he was liberated in September 1945. Steele’s paintings were based on memory because his original sketches were lost during the war. Two scenes relate to the Tayabas Road work detail in the Philippines, which created countless “unknown soldiers.” The dead were placed in individual graves with their dog tags tied to crossed sticks used as markers. Because the graves were on a flood plain, many bodies were washed away or covered with jungle. Conditions were so bad in the camp that prisoners volunteered for out-of-camp work details. For the Tayabas Road detail, men first walked 26 miles in from the railroad. Of the 325 men assigned to the road-building project, only 50 survived, making Tayabas Road the worst work detail in the Philippines.

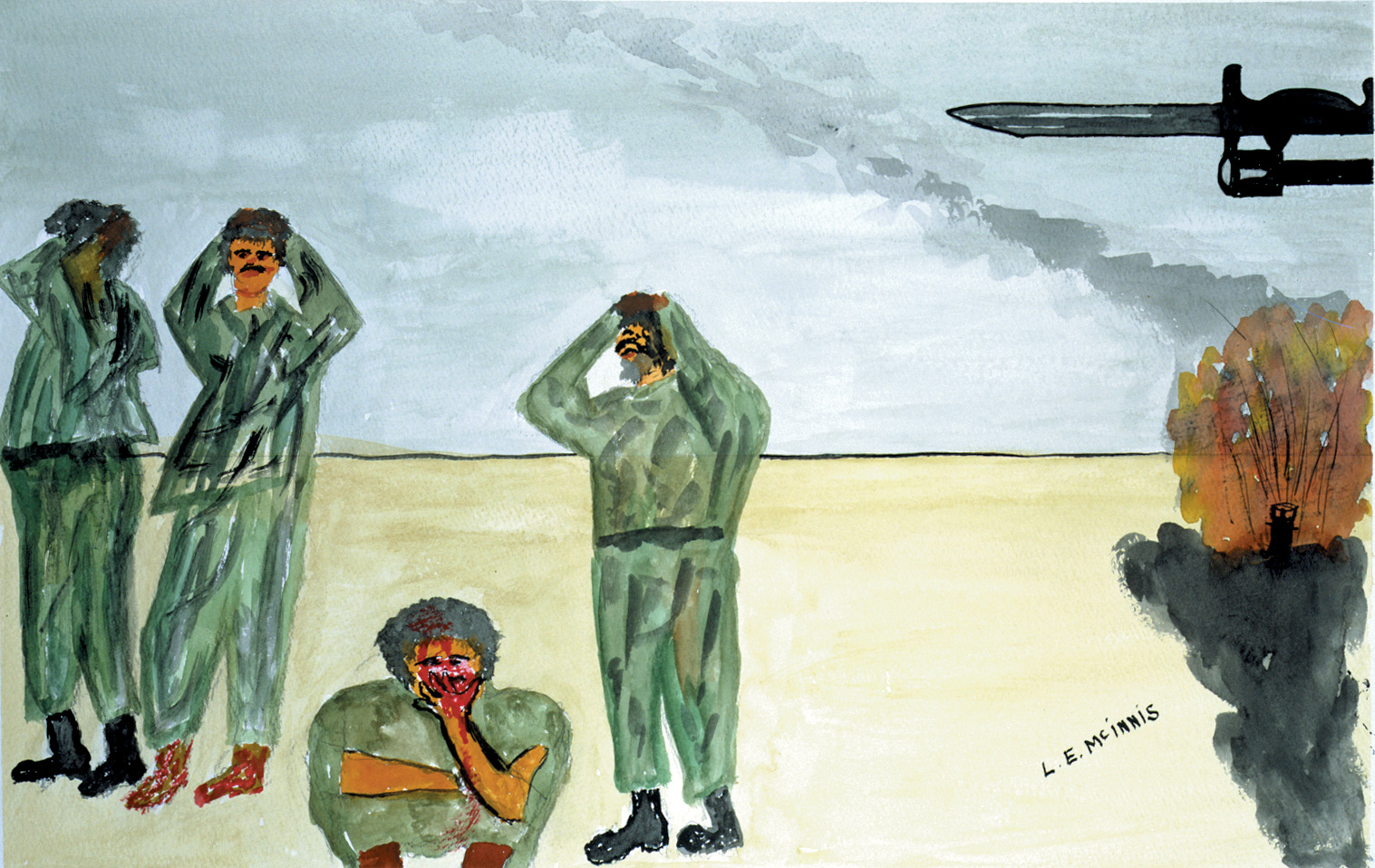

In more recent times, wars have produced their own fair share of POWs. Images of captured Egyptian tank crews during the 1973 war with Israel are haunting, as are those of Iraqis surrendering to Allied troops during Operation Desert Storm in 1991. These scenes of dejection and misery have been rendered countless times before, and will no doubt be duplicated again as long as man thinks of war as a legitimate course of action and chooses to fight his fellow man.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments