By Mason B. Webb

The U.S. 3rd Infantry Division has one of the longest legacies in the United States Army. Originally formed in November 1917 at Camp Greene, North Carolina, it gained a reputation for toughness. Because of its heroic stand in July 1918 along the Marne River in France, where a massive German attack was threatening to break through the Allied line, it fought back fiercely, earning its motto, “The Rock of the Marne.”

To the casual observer, it might seem that the men of the 3rd Infantry Division accomplished little of importance during WWII. They did not storm the beaches of Normandy. They did not capture a bridge across the Rhine. They did not liberate a Nazi concentration camp. They did not shake hands with the Russians at the Elbe.

What they did accomplish, however, has put the 3rd Infantry Division on a pedestal as one of the greatest combat divisions of the war. They had 531 days in combat—from North Africa to Czechoslovakia.

They blazed a trail of victories from Morocco to Sicily to Italy to southern France, and across southern Germany. And, along the way, 40 men of the 3rd earned the Medal of Honor—America’s highest award for valor in combat. Seventeen of the men did not live to receive their medals and the homage of a grateful nation.

After landing in French Morocco in November 1942 as part of Operation Torch, the 3rd Division quickly overran half that country. A sterner test awaited them during Operation Husky—the invasion of Sicily on July 10, 1943. A change of command brought them under Maj. Gen. Lucian K. Truscott, Jr., who would prove to be one of the great commanders of the war.

Sicily

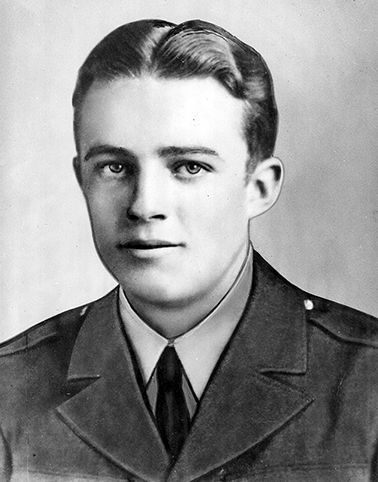

It did not take long for the first acts of extraordinary bravery to be recognized. On July 11, Scottish-born 2nd Lt. Robert Craig (15th Infantry Regiment), who had been living in Toledo, Ohio, was scouting for an enemy machine gun near Campobello, Sicily, that had halted his company’s advance about nine miles north of the division’s landing beach at Licata. Two other officers had already tried and had been wounded. Crawling to within 35 yards of the machine-gun nest, Craig charged the position and, with his carbine, killed the three crewmen.

With the obstacle eliminated, the company continued advancing and was moving down the forward slope of a hill when it came under fire by about 100 of the enemy. As his Medal of Honor citation says, “Electing to sacrifice himself so that his platoon might carry on the battle, he ordered his men to withdraw to the cover of the crest while he drew the enemy fire to himself.

“With no hope of survival, he charged toward the enemy…. He killed five and wounded three. While the hostile force concentrated fire on him, his platoon reached the cover of the crest. 2nd Lt. Craig was killed by enemy fire, but his intrepid action so inspired his men that they drove the enemy from the area, inflicting heavy casualties on the hostile force.”

Italy

Once Sicily fell to the Allies in July, the 3rd next took part in Operation Avalanche—the Fifth Army’s invasion of Italy at Salerno. After fighting its way ashore and moving northward up the mountainous spine of Italy, the Allied advance bogged down.

In order to breach the Germans’ Gustav Line that ran the width of Italy, the Allies had to cross the swift Volturno River. On October 13, 1943, Captain Arlo L. Olson of South Dakota was spearheading the 15th Regiment’s drive across the river. Leading his company, Olson waded across the Volturno’s chest-deep water, survived volleys of machine-gun fire, climbed the opposite bank, and killed the gun crew with grenades.

When another gun 150 yards away opened fire, Olson advanced upon the position. Although five Germans threw grenades at him at close range, Olson killed them all and continued forward. Closing on another position, he killed nine and seized the position.

Throughout the next 13 days, Olson led combat patrols, acted as company scout, and maintained unbroken contact with the enemy. On October 27, Olson led a platoon attack on a strongpoint, crawling to within 25 yards of the enemy, and then charging the position. Despite continuous machine-gun fire, Olson killed the crew with his pistol. When his men saw their leader’s courageous attack, they followed and overran the position.

Continuing the advance, Olson led his company to the next objective: a mountain summit. Furious automatic and small-arms fire was poured down on Olson’s company, but he ignored it and led his men charging into the enemy, driving them off.

Later, while making a reconnaissance to find defensive positions, Olson was badly wounded. Ignoring the pain, he refused medical aid but died as he was being carried down the mountain.

The autumn weather in the mountains of Italy turned wet and cold—conditions that did not seem to bother Pfc. Floyd K. Lindstrom of Colorado. On November 11, 1943, he was part of a platoon providing machine-gun support for a rifle company attacking a hill near Mignano when the Germans counterattacked, forcing the riflemen and half the machine-gun platoon to pull back.

Seeing that his small section was alone and outnumbered five-to-one, Lindstrom immediately deployed the few remaining men into position and opened fire with his single gun, which drew a heavy response. Unable to knock out the enemy position from his original location, Lindstrom lugged his own machine gun up the barren, rocky hillside to a new position, completely ignoring enemy small-arms fire that was kicking up dirt all around him.

From this new site, Lindstrom engaged the enemy gun in an intense duel. Realizing that he could not hit the Germans who had taken cover behind a large rock, he charged them under a steady stream of fire, killed both gunners with his pistol, and dragged their gun down to his own men, directing them to employ it against the enemy.

His citation reads, “Pfc. Lindstrom demonstrated aggressive spirit and complete fearlessness in the face of almost certain death.”

With the fighting stalled along the Gustav Line, anchored by the imposing, German-held Monte Cassino, the Allies looked for a way to skirt the German defenses and came up with Operation Shingle—an end run around the line that brought them ashore at the twin resort towns of Anzio and Nettuno. Truscott’s division comprised part of the invasion force.

Shortly after landing, the 3rd moved northward in an attempt to take the key town of Cisterna that controlled a network of roads that would be needed for further operations in the advance on Rome. On January 28, a remarkable soldier performed a remarkable deed. Tech. 5 Eric Gunnar Gibson, a Sweden-born, Chicago-raised cook (Company I, 30th Infantry Regiment) was part of the advance on Cisterna.

A few miles from Cisterna, German troops launched an attack against Gibson’s company. Although not an infantryman, Gibson saw the danger that the assault posed to his unit’s right flank, swiftly organized a small group of green replacements who had not been in combat before, grabbed a Thompson submachine gun, and rushed toward the danger.

During his ad hoc squad’s assault, Gibson personally killed five Germans and took two others prisoner. Not yet finished, he then went running, leaping, and dodging through machine-gun fire to single-handedly wipe out another position.

The cook continued his assault, moving down a ditch and keeping pace with his company’s advance toward other German positions even though enemy shells and bullets were falling all about him.

Gibson killed one German before an explosion knocked him flat. He continued on—firing, advancing, firing again, reloading, and firing some more. Halting his men before going around a bend in a ditch, Gibson went forward alone to reconnoiter. There he was hit and killed.

Two days after Gibson’s heroics, Medic Pfc. Lloyd C. Hawks, from Minnesota, was trying to rescue two wounded men when the Germans counterattacked. Hawks crawled 50 yards through a veritable hail of machine-gun bullets and flying mortar fragments into a small ditch, administered first aid to a fellow medic who had sought cover there, and continued toward the two wounded men.

A bullet knocked Hawks’ helmet off, momentarily stunning him; 13 bullets punctured his helmet as it lay on the ground next to him. Undeterred, Hawks crawled to the casualties, administered first aid to the more seriously wounded man, and dragged him to a covered position 25 yards distant.

Braving continuous fire from nearby positions, and shells that exploded around him, Hawks returned to the second man and administered first aid. As he raised himself to obtain bandages from his medical kit, a burst of machine-gun fire tore into his right hip; a second burst splintered his left forearm.

Despite severe pain and his bloody, dangling left arm, Hawks completed bandaging the casualty and, with superhuman effort, dragged him to the same ditch to which he had brought the first man. He then crawled back 75 yards to reach his company and get more aid for the wounded men.

While Hawks survived his wounds, another 3rd Division soldier, Sergeant Truman O. Olson, did not. On the night of January 30, 1944, during the continued fighting for Cisterna, Olson, a machine gunner with Company B, 7th Infantry Regiment, saw his unit being decimated.

After a 16-hour assault on enemy positions, in the course of which over one-third of Company B became casualties, the survivors dug in behind a small hill. Olson and his crew, with the one available machine gun, were placed forward of their lines and in an exposed position to bear the brunt of the expected German counterattack.

Although exhausted, Olson stuck grimly to his post all night while his gun crew was picked off one by one by accurate enemy fire. At daybreak, weary from over 24 hours of continuous battle and suffering from an arm wound, Olson manned his gun alone, meeting the full force of an all-out enemy assault by approximately 200 men supported by mortars and machine-guns.

Olson knew that only his weapon stood between his company and complete destruction; he refused evacuation. For 90 minutes after receiving a second and fatal wound, he remained at his gun, killing at least 20 of the enemy, wounding many more, and stopping the enemy assault. By sacrificing his life, Olson saved his company from certain annihilation.

Pfc. John C. Squires, of Company A, 30th Infantry, was serving as his platoon’s messenger when, at the start of his company’s attack on strongly held enemy positions in and around Spaccasassi Creek, near Padiglione, Italy, on the night of April 23-24, 1944, he braved intense artillery, mortar, and antitank fire on a reconnaissance mission.

Squires reconnoitered a new route of advance and informed his platoon leader of the alternate route. On his own initiative, he then rounded up stragglers, organized a group of lost men into a squad, and led them forward. When the platoon reached Spaccasassi Creek and established an outpost, Squires placed the men in position.

After his platoon had been reduced to 14 men, Squires twice brought up reinforcements. On each trip he went through barbed wire and across an enemy minefield while under intense German fire.

Squires’s outpost was attacked three times the next morning. Each time, Squires ignored the enemy’s attempts to kill him, and fired hundreds of rounds of rifle, BAR, and captured German machine guns at the enemy, inflicting numerous casualties and materially aiding in repulsing the attacks.

Later, Squires moved 50 yards south of the outpost and engaged 21 Germans in individual machine-gun duels at point-blank range, forcing the enemy to surrender and capturing 13 more machine guns. He then placed the captured guns in position and instructed other members of his platoon in their operation.

The next night, during another attack, he killed three and wounded several more with captured grenades and fire from his captured gun. Squires was killed a month later during the breakout from the beachhead that took place on May 23, 1944. The Allies, who had been stuck at Anzio since January, combined with the other Allied forces along the Gustav Line in one overwhelming, violent push toward Rome.

Also on that same first day of the breakout, near Ponte Rotto, Pfc. Patrick L. Kessler and his Company K, 30th Infantry, came under intense German fire. Acting without orders, Kessler formed an assault group to destroy a machine gun that had killed five of his comrades and halted the advance of his company.

With three men laying down fire, Kessler crawled to within 50 yards of the enemy machine gun before he was discovered, whereupon he plunged headlong into the furious German automatic fire.

Reaching the emplacement, he stood over it and killed two men and captured a third. After taking his prisoner to the rear, Kessler saw others in his company being killed and wounded while assaulting an enemy strongpoint.

Kessler grabbed a wounded man’s BAR and rushed toward the strongpoint, 100 yards away. Although two machine guns concentrated their fire directly at him and exploding shells knocked him down, Kessler crawled through a minefield to a point within 50 yards of the enemy and engaged the machine gunners in a duel.

When an artillery shell burst close to him, Kessler advanced upon the position in a slow walk, firing his BAR from the hip. Although the enemy fired at him, he continued his advance, killing the gunners and capturing 13 others.

While taking his prisoners to the rear, two snipers fired on him. Several of his prisoners attempted to escape, but Kessler fired on either flank of them, forcing them to ground, and then engaged the snipers in a firefight, and captured them. With this last threat removed, Company K continued its advance, capturing its objective without further opposition. Pfc. Kessler was killed two days later.

The division’s 15th Medal of Honor went posthumously to Sergeant Sylvester Antolak, from St. Clairsville, Ohio. On May 24, near Cisterna, he single-handedly engaged a German machine-gun nest by running 30 yards ahead of his squad from Company B, 15th Infantry. As he ran, bullets struck him three times, knocking him to the ground, but each time he got up and staggered forward.

With his right arm shattered, he switched his Thompson sub-machine gun to his left hand and continued his attack. He closed within 15 yards of the enemy strongpoint, where he opened fire, killing two Germans and capturing the remaining ten.

Antolak reorganized his men and, refusing to seek the medical attention he so badly needed, led the way toward another strongpoint 100 yards distant. Completely disregarding the bullets aimed at him, he stormed ahead toward the strongpoint when he was instantly killed by enemy fire.

Inspired by his example, his squad went on to overwhelm the enemy troops. By his supreme sacrifice, superb fighting courage, and heroic devotion to the attack, Antolak was directly responsible for eliminating 20 Germans and clearing the way for his company’s advance.

On to Rome

In early June, the Allied forces at Anzio had broken through the German encirclement and were on their way to Rome, which the Germans had declared to be an “open city.” But some German units were loath to give it up without a fight. Two 3rd Division men from the same unit would both earn the Medal of Honor during the same action, but both would lose their lives in the process.

At 1 a.m. on June 3, Privates Herbert F. Christian and Elden H. Johnson, Company E, 15th Infantry, were part of a night patrol near the mountain town of Valmontone, southeast of Rome, when the patrol was ambushed by an overwhelming force of approximately 60 riflemen, three machine guns, and three tanks from positions only 30 yards away.

Flares illuminated the scene, and Christian, from Steubensville, Ohio, signaled for the patrol to withdraw while he remained to fight. A 20mm shell then blew off his right leg but Christian advanced on his left knee and the bloody stump of his right thigh, firing his Thompson and killing three enemy soldiers. Despite excruciating pain, Christian continued on his self-assigned mission, leaving a bloody trail behind him. He made his way forward into intense fire and killed another German.

Nearby, his buddy Johnson, from New Jersey, was hit in the stomach by machine-gun bullets, but he and Christian kept up a brave fusillade that enabled the rest of the patrol to escape.

Reloading his weapon, Christian fired directly into the enemy, who seemed to be enraged at his audacity and concentrated all their weapons at him. Still on his knee and stump, Christian fired his weapon to the very last. Just as he emptied his Thompson, enemy bullets found their mark and Christian fell dead, beside Johnson.

Operation Dragoon

Two days after the Allies took Rome, Operation Overlord, the Normandy invasion, was launched. A second invasion of France, named Operation Dragoon, took place on August 15—and the 3rd Infantry Division was transferred from Fifth Army command to Seventh Army for the initial landing.

Two days after the landings, S/Sgt. Stanley Bender, of Company E, 7th Infantry, climbed atop a knocked-out tank near La Londe-les-Maures, France, in the face of heavy machine-gun fire that had halted the advance of his company, in an effort to locate the source of this fire. Although bullets ricocheted off the tank, Bender nevertheless remained standing upright in full view of the enemy for over two minutes.

Spotting muzzle flashes from the enemy machine guns 200 yards away, he ordered two squads to cover him while he led his men down a ditch, and ran a gantlet of intense machine-gun fire that completely blanketed 50 yards of his advance and wounded four of his men.

While the Germans hurled grenades into the ditch, Bender stood his ground until his squad caught up with him, then advanced alone, in a wide flanking approach, to the rear of the knoll. Walking 40 yards without cover, he reached the first machine gun and knocked it out with a single short burst.

He then ignored bursting hand grenades and made his way toward the second machine gun, 25 yards away. Miraculously, he was not hit; reaching the edge of the emplacement, the Chicagoan dispatched the crew. Signaling his men to rush the rifle pits, he then continued on to kill another enemy rifleman and returned to lead his squad in the destruction of the eight remaining Germans in the strong point.

His display of courage so inspired the remainder of the assault company that the men charged out of their positions, shouting and yelling, to overpower the enemy roadblock and sweep into town, knocking out two antitank guns, killing 37 Germans, and capturing 26 others. The attack also resulted in the capture of three bridges over the Maravenne River and command of key terrain in southern France.

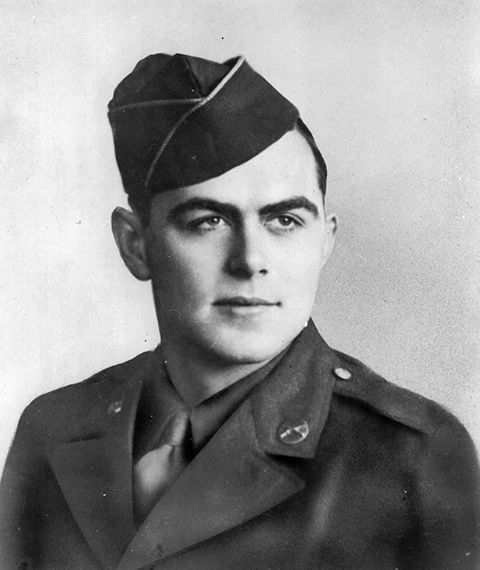

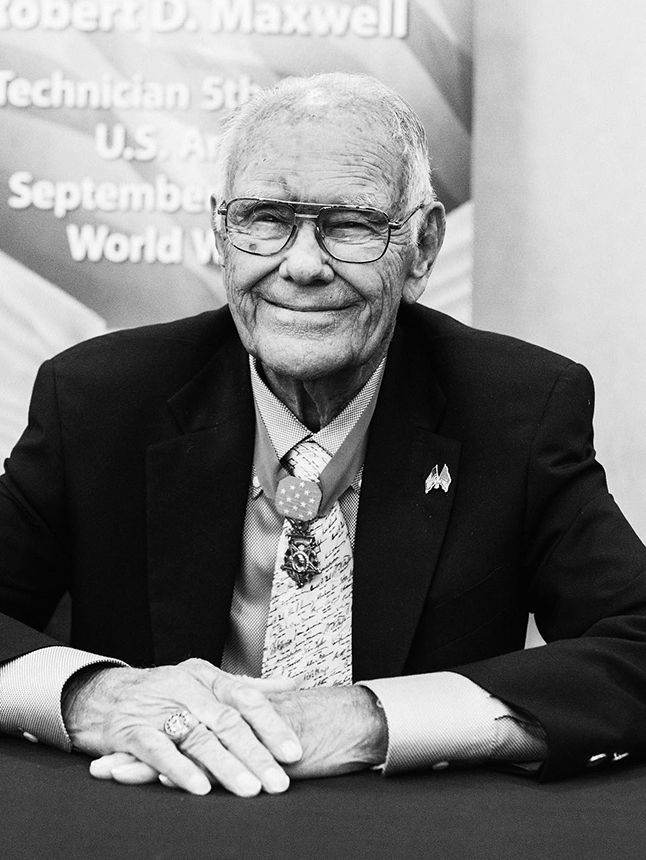

By early September 1944, Seventh Army drive had advanced up the French-Swiss border to Alsace-Lorraine, where the 3rd met ever-increasing resistance by Germans determined to prevent an invasion of the Nazi homeland. At Besançon on September 7, Tech. 5 Robert D. Maxwell, HQ Company, 7th Infantry, and three other soldiers, armed only with .45-caliber pistols, defended the battalion observation post against a platoon of heavily armed Germans.

Maxwell aggressively fought off advancing enemy elements and, by his calmness, tenacity, and fortitude, inspired his comrades to continue the unequal struggle. When an enemy grenade was tossed in the midst of his squad, Maxwell unhesitatingly threw himself on it, using his body to absorb the explosion. This heroic act permanently maimed Maxwell, but saved the lives of his comrades and allowed for the temporary withdrawal of the battalion’s forward headquarters.

On September 12, 1944, 1st Lt. John J. Tominac, from Conemaugh, Pennsylvania, a platoon leader in Company I, 15th Infantry, was engaged in a battle near Saulx de Vesoul, France, north-northeast of Besançon. Tominac seized the initiative to take out a German roadblock; he ran alone across 50 yards of open ground while being targeted by a machine-gun crew.

Killing the crew with a burst from his Thompson, he then led one of his squads to wipe out another strongpoint, killing about 30 of the enemy. Reaching the outskirts of the small village, he and a Sherman tank proceeded to attack a 77mm self-propelled gun, but the SP gun knocked out the tank and a fragment from the blast wounded Tominac.

Shaking off the wound, he climbed onto the burning tank and used its .50-caliber machine gun to neutralize the German position. Although painfully wounded, he allowed a sergeant to dig shrapnel out of his shoulder but refused further medical attention. He then led his unit in a grenade attack against a fortified position occupied by 32 Germans and compelled them to surrender.

His display of courage and leadership resulted in the destruction of four successive enemy defensive positions, the surrender of a vital sector of Saulx de Vesoul, and the deaths or capture of at least 60 of the enemy. Tominac survived his wounds and went on the serve in Korea and Vietnam.

On September 17, 1944, at Raddon-et-Chapendu, France, (not far from Besançon), a determined German assault on 3rd Division forces took place. Squad leader Sergeant Harold O. Messerschmidt, Company L, 30th Infantry, was with his men holding the high ground when the Germans attacked.

Seriously wounded during the firefight, Messerschmidt, from Chester, Pennsylvania, killed five attackers and wounded several others with his Thompson. With the rest of his squad dead or wounded, Messerschmidt held off the enemy by using his sub-machine gun as a club until he was overwhelmed and killed.

S/Sgt. Clyde M. Choate, Company C, 601st Tank Destroyer Battalion, was commanding an M-10 tank destroyer in the Vosges Mountains near Bruyères, France, on October 25, 1944. With 3rd Division infantrymen occupying a hilltop position, a panzer and an infantry company attacked, threatening to overrun the Americans and capture a command post.

Choate’s TD was set afire by two hits. After he and his crew abandoned it and reached comparative safety, Choate returned to rescue comrades trapped inside, braving enemy fire which ripped his jacket and tore the helmet from his head.

Completing the search, and seeing the panzer and its supporting infantry overrunning GIs in their shallow foxholes, he grabbed a bazooka and ran after the panzer, firing a rocket from a distance of 20 yards, immobilizing it but leaving it still able to fire its cannon and machine-gun.

Obtaining another bazooka, he reached a position 10 yards from the tank. His shot shattered the turret; with his pistol he killed two of the crew as they emerged. Then, charging the crippled tank while enemy infantry sniped at him, he dropped a grenade inside to complete its destruction.

With their armor gone, the enemy infantry fled. Choate’s great daring in assaulting an enemy tank single-handed, his determination to follow the vehicle after it had passed his position, and his skill and thoroughness in the attack prevented the enemy from capturing the battalion CP and turned a probable defeat into a tactical success.

Fighting was still raging near St. Die on November 7 when Pfc. William F. Leonard, a squad leader in Company C, 30th Infantry, faced the test of his life. Although his platoon was reduced to eight men, Leonard was leading the survivors in an assault over a wooded hill that the Germans blanketed with automatic-weapons fire.

Ignoring bullets that pierced his pack, Leonard killed two snipers and destroyed a machine-gun nest with grenades. Though momentarily stunned by an exploding shell, Leonard relentlessly advanced, knocking out a second machine-gun nest and capturing the roadblock objective.

Leonard, from Lockport, Washington, did not receive the medal until 28 years after his death, when President Barack Obama presented it to his three daughters in 2014.

On December 23, S/Sgt. Gus Kefurt and his Company K, 15th Infantry, were attacking near Bennwihr, France. Kefurt jumped through an opening in a wall—only to be confronted by 15 Germans. Although outnumbered, he opened fire, killing 10 and capturing the others.

A panzer soon rolled up, but Kefurt destroyed it by calling for an artillery strike. When night fell, he maintained a three-man outpost in Bennwihr in the middle of the German positions, and successfully fought off several German attempts to eliminate his position.

Assuming command of his platoon the following morning, he led it in hand-to-hand fighting through Bennwihr until blocked by a panzer. Using rifle grenades, he forced the surrender of its crew. He then continued his attack from house to house against heavy enemy fire.

Advancing against a strongpoint that was holding up the company, his platoon was subjected to a counterattack and infiltration to its rear. During this time he killed approximately 15 of the enemy at close range. Although severely wounded in the leg, he refused treatment. Although suffering heavy casualties in their exposed position, the men remained steadfast due to Kefurt’s personal example of bravery, determination, and leadership.

When the forces to his rear were pushed back three hours later, he refused to be evacuated but, instead, during several more counterattacks, moved painfully about under intense small-arms and mortar fire, stiffening the resistance of his platoon by encouraging individual men and by his own fire until he was killed. As a result of S/Sgt. Kefurt’s gallantry, the position was maintained.

On December 27, 1st Lt. Eli Whitely and his platoon from Company L, 15th Infantry, were engaged in savage house-to-house fighting through Sigolsheim. While attacking a German-held house, his unit came under heavy machine-gun and mortar fire and he was wounded in the left arm and shoulder.

Despite his wounds, he charged alone into the house and killed its defenders. Hurling smoke and fragmentation grenades, Whitely reached the next house and stormed inside, killing two and capturing eleven. He continued leading his platoon in the extremely dangerous task of clearing hostile troops from strongpoints along the street.

Despite the fact that his left arm was useless, the bespectacled Texan led his men in assaulting the buildings and rooting out the defenders. Armed with a bazooka, he blew a hole in one house and, after trading the bazooka for a Thompson, charged inside through a curtain of bullets.

With the Thompson, he killed five Germans and forced another 12 to surrender. As he emerged to continue his attack, he was again hit. In agony and with his right eye pierced by a shell fragment, he shouted for his men to follow him to the next house. He remained in command of his platoon until forcibly evacuated.

By disregarding his personal safety, his aggressiveness while suffering from severe wounds, his determined leadership, and superb courage, 1st Lt. Whiteley spearheaded an attack that cracked the core of enemy resistance in a vital area.

Whitely survived the war and went on to teach at Texas A&M University.

The new year saw no let-up in the fighting for the 3rd Division, and deadly combat was still continuing in the snow-covered Colmar suburb of Kaysersberg. On January 8, T/Sgt. Russell E. Dunham, Company I, 30th Infantry, was taking part in an attack on Hill 616. Carrying a carbine, 12 carbine magazines, and a dozen grenades, he set off to eliminate three machine-gun nests that were keeping his company pinned down.

Supported by two machine guns and, with the rest of his platoon behind him, the sergeant from Illinois crawled 75 yards under heavy fire toward the timbered emplacement shielding the machine gun on the left. As he jumped to his feet 10 yards from the gun and charged forward, bullets slashed a 10-inch gash across his back, sending him spinning 15 yards downhill into the snow.

When Dunham renewed his one-man assault, a grenade landed beside him. He kicked it aside and, as it exploded five yards away, shot and killed the German machine gunner and assistant gunner.

Dunham jumped into the emplacement and captured the third member of the gun crew. Although his back wound was intensely painful, Dunham ran 50 yards through a storm of enemy fire to attack the second machine gun.

He resumed his attack, throwing two grenades and destroying another gun and its crew; he then fired down into the supporting foxholes, dispatching and dispersing the enemy riflemen. Not yet finished, Dunham continued toward enemy positions farther up the hill. With grenades exploding around him, and coming under machine-gun fire to his front, he hit the ground and crawled forward. At 15 yards range, he jumped up, staggered a few paces toward the timbered machine-gun emplacement and killed the crew with grenades.

An enemy rifleman fired at point-blank range, but missed him. After killing the rifleman, Dunham drove others from their foxholes with grenades and carbine fire. By killing nine Germans, wounding seven, and capturing two, T/Sgt. Dunham, despite his painful wound, spearheaded a spectacular and successful diversionary attack.

On January 25, 1945, Pfc. Jose F. Valdez, from Pleasant Grove, Utah, and a BAR man with Company B, 7th Infantry, was on a patrol with five others near Rosenkrantz, France, when the enemy counterattacked with overwhelming strength. From his position near some woods 500 yards beyond the American lines, he saw an approaching panzer and raked it with automatic rifle fire until it withdrew.

Soon afterward, he saw three Germans stealthily approaching through the woods. Scorning cover as the enemy soldiers opened up with machine-gun fire from a range of 30 yards, he engaged in a firefight with the attackers until he had killed all three.

The enemy then launched an attack with two full infantry companies, blasting Valdez’s position with concentrations of automatic and rifle fire and beginning an encircling movement that forced the patrol leader to order a withdrawal.

Despite the terrible odds, Valdez immediately volunteered to cover the maneuver, and, as the patrol withdrew under fire American lines, he fired burst after burst into the swarming enemy.

Three of his companions were wounded in their dash for safety and Valdez was hit by a bullet that severed his spinal cord. Paralyzed from the waist down, Valdez fell into a firing position and delivered a protective screen of fire until all others of the patrol were safe.

By field telephone he called for artillery and mortar fire, correcting the range until shells were falling within 50 yards of his position. For 15 minutes he refused to be dislodged by more than 200 of the enemy. Then, seeing that the barrage had broken the counterattack, he dragged himself back to his own lines. He died of his wounds three weeks later.

Through his valiant stand that cost him his life, Pfc. Valdez was directly responsible for repulsing an attack by vastly superior enemy forces and made it possible for his comrades to escape.

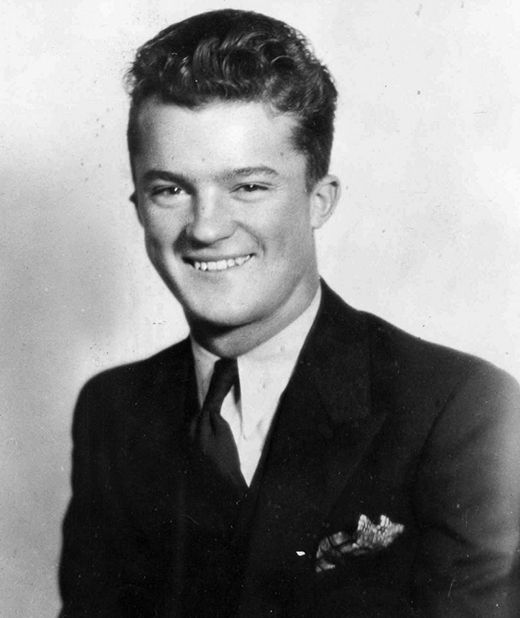

The 36th member of the 3rd Division to earn the Medal of Honor is undoubtedly the division’s most famous. 2nd Lt. Audie L. Murphy, of Kingston, Texas, was commanding Company B, 15th Infantry, near Holtzwihr, France, on January 26, 1945, when the unit was attacked by six tanks and waves of infantry.

Murphy ordered his men to withdraw to prepared positions in a forest while he remained forward at his CP and continued to give fire directions to the artillery by telephone. Behind him, to his right, a U.S. tank destroyer received a direct hit and began to burn; its crew escaped.

With enemy panzers closing in, Murphy climbed onto the burning TD, which was in danger of exploding at any moment, and employed its .50-caliber machine gun against the enemy. With Germans attacking from three sides, Murphy continued firing, killing dozens of Germans and causing their infantry attack to waver. The enemy tanks, losing infantry support, began to fall back.

For an hour the Germans tried eliminating Murphy, but he stayed at his gun, wiping out a squad creeping up on his right flank. Overall, his directing of artillery fire, and action on the machine gun, killed or wounded at least 50 Germans.

Wounded in the leg, Murphy continued firing until his ammunition was exhausted. Making his way back to his company, he refused medical attention and organized a counterattack that forced the German withdrawal.

Murphy’s courage and his refusal to give ground saved his company from possible encirclement and destruction, and enabled it to hold the woods which had been the enemy’s objective.

Audie Murphy became the most-decorated American soldier of World War II. After the war, his wartime exploits and boyish good looks brought him fame as a Hollywood movie star.

Into Germany

German resistance in Alsace-Lorraine finally ended, and the U.S. Seventh Army, including the 3rd Infantry Division, crossed the border into Nazi Germany. After fighting its way through towns, villages, forests, and across rivers, it reached Nuremberg in mid-April 1945.

The scene of Hitler’s huge and dramatic Nazi Party rallies in the 1930s, Nuremberg was considered the citadel of Third Reich fanaticism and was stubbornly defended by some of the most hard-core troops that Germany had left.

1st Lt. Frank Burke, the 1st Battalion, 15th Infantry’s transportation officer, was looking for a place for the battalion motor pool when he decided to perform more than his assigned duties and participate in the fight.

Advancing beyond the front lines and, detecting Germans preparing for an attack, he rushed back to a nearby American unit, secured a machine gun and ammunition, and daringly opened fire on this superior force, which deployed and returned his fire with machine pistols, rifles, and rocket launchers.

A German machine gun fired on him but the lieutenant from New Jersey killed this gun crew and drove off the survivors of the unit he had originally attacked. Out of ammunition, he picked up a rifle, and dashed more than 100 yards through enemy fire when a sniper in a cellar only 20 yards away nearly hit him, but Burke ran to the basement window and fired a full clip into his would-be killer. Burke then secured grenades and continued to hunt Germans.

At one point, he pulled the pins from two grenades and, holding one in each hand, rushed toward an enemy-held building, tossing his explosives just as the enemy threw a grenade at him.

In the simultaneous triple explosion, the Germans were wiped out and Burke was dazed. His citation reads, “He emerged from the shower of debris that engulfed him, recovered his rifle, and went on to kill three more Germans and meet the charge of a machine-pistolman, whom he cut down with three calmly delivered shots. He then retired toward American lines and there assisted a platoon in a raging,

30-minute fight against formidable armed hostile forces.

“In four hours of heroic action, 1st Lt. Burke single-handedly killed 11 and wounded three enemy soldiers, and took a leading role in engagements in which an additional 29 enemy were killed or wounded. His extraordinary bravery and superb fighting skill were an inspiration to his comrades, and his entirely voluntary mission into extremely dangerous territory hastened the fall of Nuremberg in his battalion’s sector.”

In a wooded area a few miles north of Nuremberg, on April 18, Private Joseph F. Merrell, from Staten Island, New York, was involved with his unit’s (Company I, 15th Infantry) attempt to take a German-occupied hill. The company was pinned down by brutal fire.

Entirely on his own initiative, Merrell began a single-handed assault. He ran 100 yards through concentrated fire, somehow barely escaping death at each stride, and at point-blank range engaged four Germans, killing them all while bullets ripped through his uniform.

Continuing on, a sniper’s bullet smashed his rifle, leaving him armed only with three grenades. Without hesitation, he zigzagged another 200 yards through heavy fire. Reaching a machine-gun nest, he hurled two grenades and then jumped into the gun emplacement, where he grabbed a Luger pistol and killed several Germans that had survived the grenade blast.

Rearmed, he crawled toward the second machine gun 30 yards away, killing four men in foxholes on the way, but himself receiving a critical wound in the abdomen.

And yet on he went, staggering, bleeding, disregarding bullets that ripped through his clothing and glanced off his helmet. He threw his last grenade into the second machine-gun nest and stumbled on to wipe out the crew just as an enemy bullet killed him.

His citation says, “In his spectacular, one-man attack, Pvt. Merrell killed six Germans in the first machine-gun emplacement, seven in the next, and an additional 10 infantrymen who were astride his path to the weapons which would have decimated his unit had he not assumed the burden of the assault and stormed the enemy positions with utter fearlessness, intrepidity of the highest order, and a willingness to sacrifice his own life so that his comrades could go on to victory.”

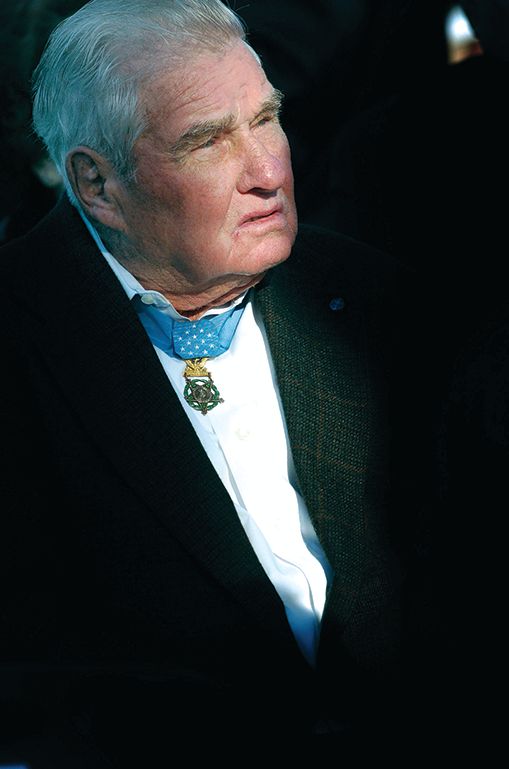

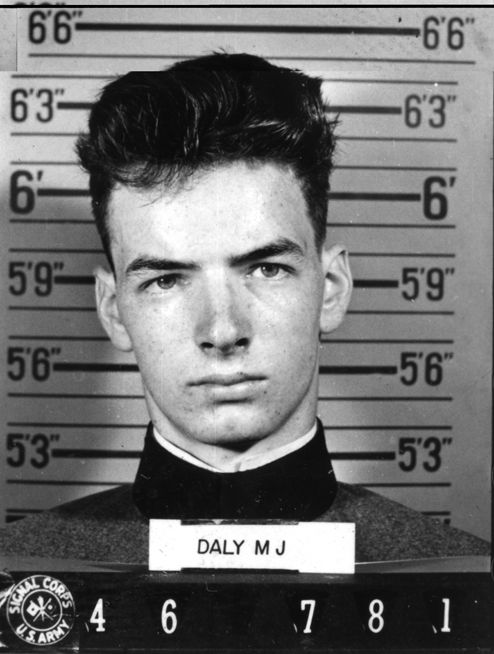

The 3rd Division’s 40th and final Medal of Honor was earned by 19-year-old 1st Lt. Michael J. Daly of Southport, Connecticut. Commanding Company A, 15th Infantry, Daly was leading his men through the shell-battered, sniper-infested wreckage of Nuremberg when a sudden burst of machine-gun fire caught his unit in an exposed position.

Ordering his men to take cover, Daly dashed forward alone, and, as bullets struck about him, shot the gun crew. Resuming the advance, he located a six-man enemy patrol armed with rocket launchers, which threatened friendly armor.

He again went forward alone to engage the patrol but became the target for their concentrated fire. Despite the danger, he calmly fired at the patrol until he had eliminated them all.

With his company struggling to keep up, Daly entered a park where a machine-gun crew, lying in wait, opened fire. Daly shot the gunner, then directed his men to take out the rest of the crew; they did.

In a final duel, Daly wiped out a third machine-gun emplacement with rifle fire at close range. By fearlessly engaging in four single-handed firefights, Lieutenant Daly, voluntarily taking all major risks himself and protecting his men at every opportunity, killed 15 Germans, silenced three enemy machine-guns, and wiped out an entire rocket-armed enemy patrol. His heroism during the lone bitter struggle with fanatical enemy forces was an inspiration to the valiant Americans who took Nuremberg.

These 17 Additional MoH Recipients Inspired Their Comrades

In addition to the heroic deeds described in this article, 17 other men of the 3rd Infantry Division performed equally courageous acts that earned for them their nation’s highest award for valor:

SICILY:

Waybur, 1st. Lt. David C.; 15th Infantry Regiment; July 17, 1943, near Agrigento

ITALY:

Britt, 1st Lt. Maurice L.; 30th Infantry Regiment; November 10, 1943, north of Mignano

Knappenberger, Pfc. Alton W.; 30th Infantry Regiment; February 1, 1944; near Cisterna di Littoria

Dutko, Pfc. John W.; 30th Infantry Regiment; May 23, 1944, near Ponte Rotto

Schauer, Pfc. Henry; 15th Infantry Regiment; May 23, 1944, near Cisterna di Littoria

Mills, Private James H. Mills; 15th Infantry Regiment; May 24, 1944, near Cisterna di Littoria

Davila, S/Sgt. Rudolph B.; 7th Infantry Regiment; May 28, 1944, Artena

FRANCE:

Connor, Sergeant James P.; 7th Infantry Regiment; August 15, 1944, Cape Cavalaire

Zussman, 2nd Lt. Raymond; 756th Tank Battalion; Sept. 12, 1944, Noroy le Bourg

Schwab, 1st. Lt. Donald K.; 15th Infantry Regiment; September 17, 1944, Lure

2nd. Lt. James L. Harris; 756th Tank Battalion; October 7, 1944, Vagney

Kandle, 1st Lt. Victor L.; 15th Infantry Regiment; October 9, 1944, near La Forge

Adams, S/Sgt. Lucian; 30th Infantry Regiment; October 28, 1944, near St. Die

Private Wilburn K. Ross; 30th Infantry Regiment; October 30, 1944, near St. Jacques

Murray, Jr., 1st. Lt. Charles P.; 30th Infantry Regiment; December 16, 1944, near Kaysersberg

Ware, Lt. Col. Keith; 15th Infantry Regiment; December 26, 1944, near Sigolsheim

Peden, Tech.5 Forrest E.; 10th Field Artillery Battalion; February 3, 1945, near Biesheim

Such was the heroism of the men of the 3rd Infantry Division, who performed their missions above and beyond the call of duty—often at the cost of their lives.

I always appreciate articles related to the Medal of Honor in WWII; well done. I would point out one factual error however, you correctly name all 42 members of the 3rd Division to earn the Medal of Honor, but in the introduction you state that 40 men received it.

Amazing leadership, astounding bravery. Why aren’t the names of heros like these men on our streets, schools, and public buildings?

in 1972 I was stationed in Nuremberg Germany at Merrell barracks which was named after Joseph Merrell Medal of Honor recipient.