By Robert L. Durham

Confederate infantry on the northeastern outskirts of Port Republic in the Shenandoah Valley charged up the slopes of a ravine on June 9, 1862, against Union artillery that had been ravaging their ranks all morning. The Union cannoneers fired canister at the advancing Confederates, but they kept coming.

Federal infantry protecting the battery fought back desperately. With no time to reload, the opposing infantry fought with bayonets, clubbed muskets, and fists. The Union artillerists used their rammers and extractors as bludgeons. Not even the horses escaped the bloodbath as the Confederates shot them to prevent the Union artillery from limbering their guns. The action was the turning point in two days of hard fighting in the broad expanse of the valley south of the southern terminus of the Massanutten Mountain.

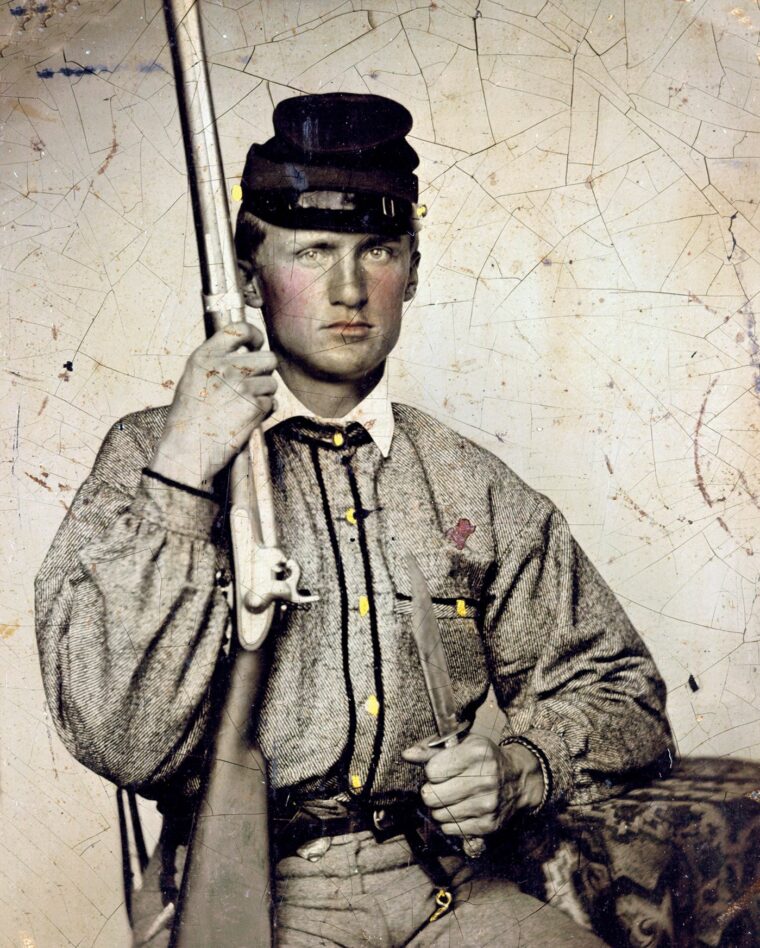

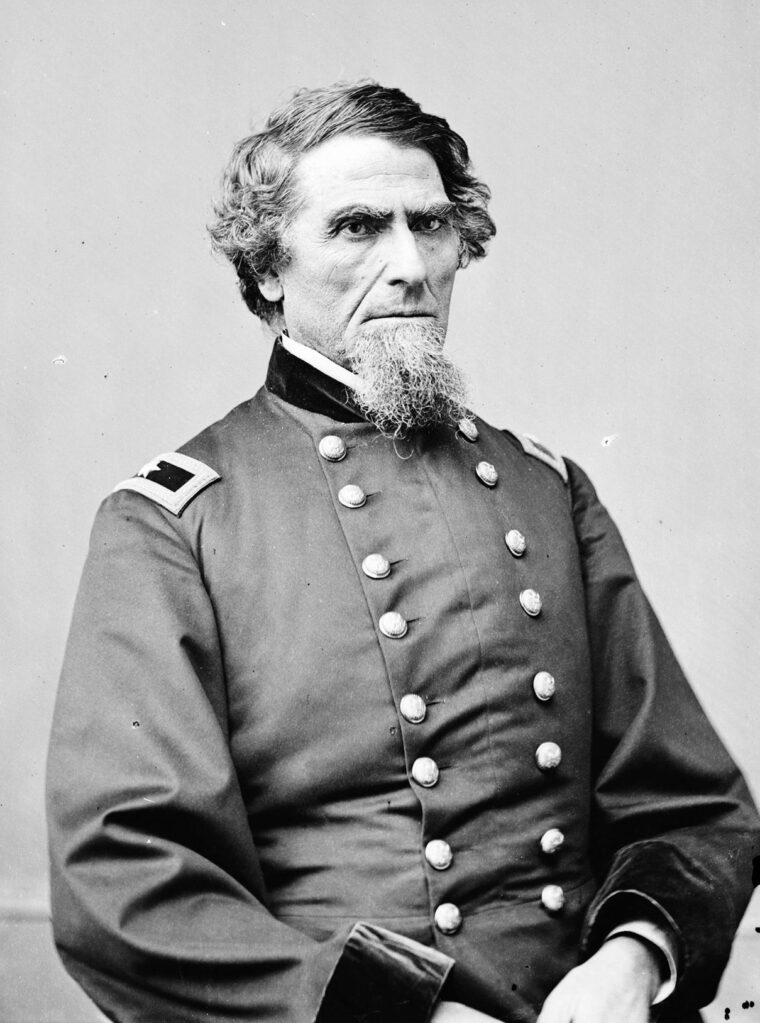

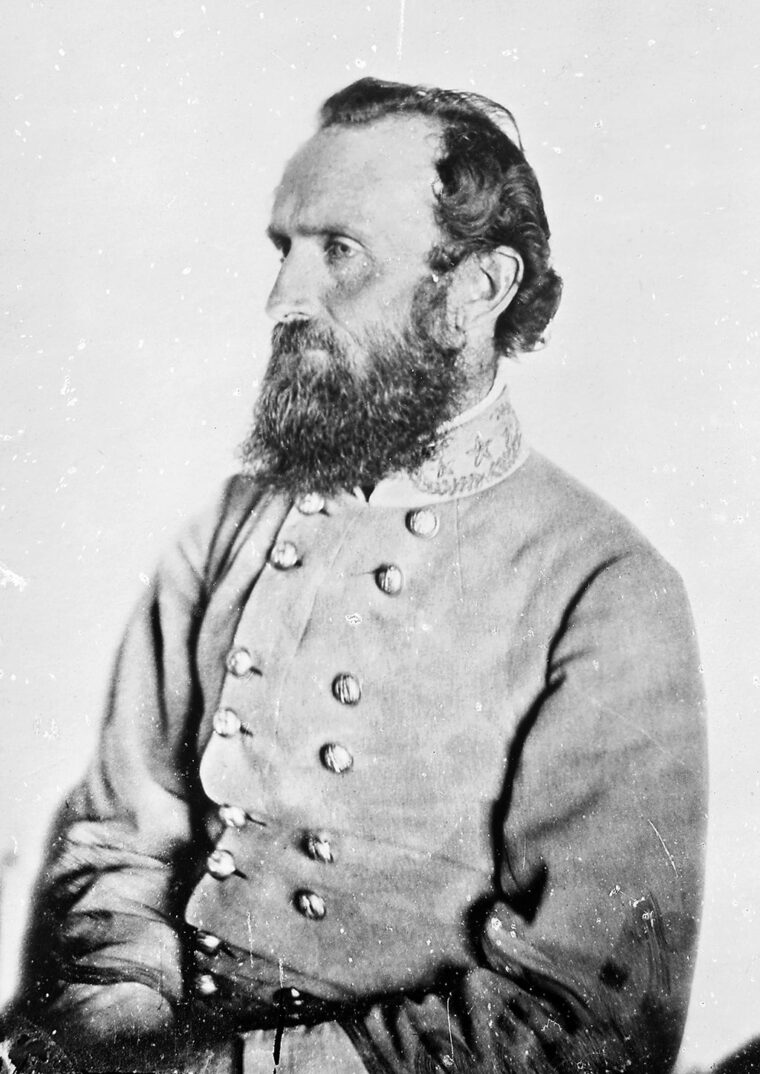

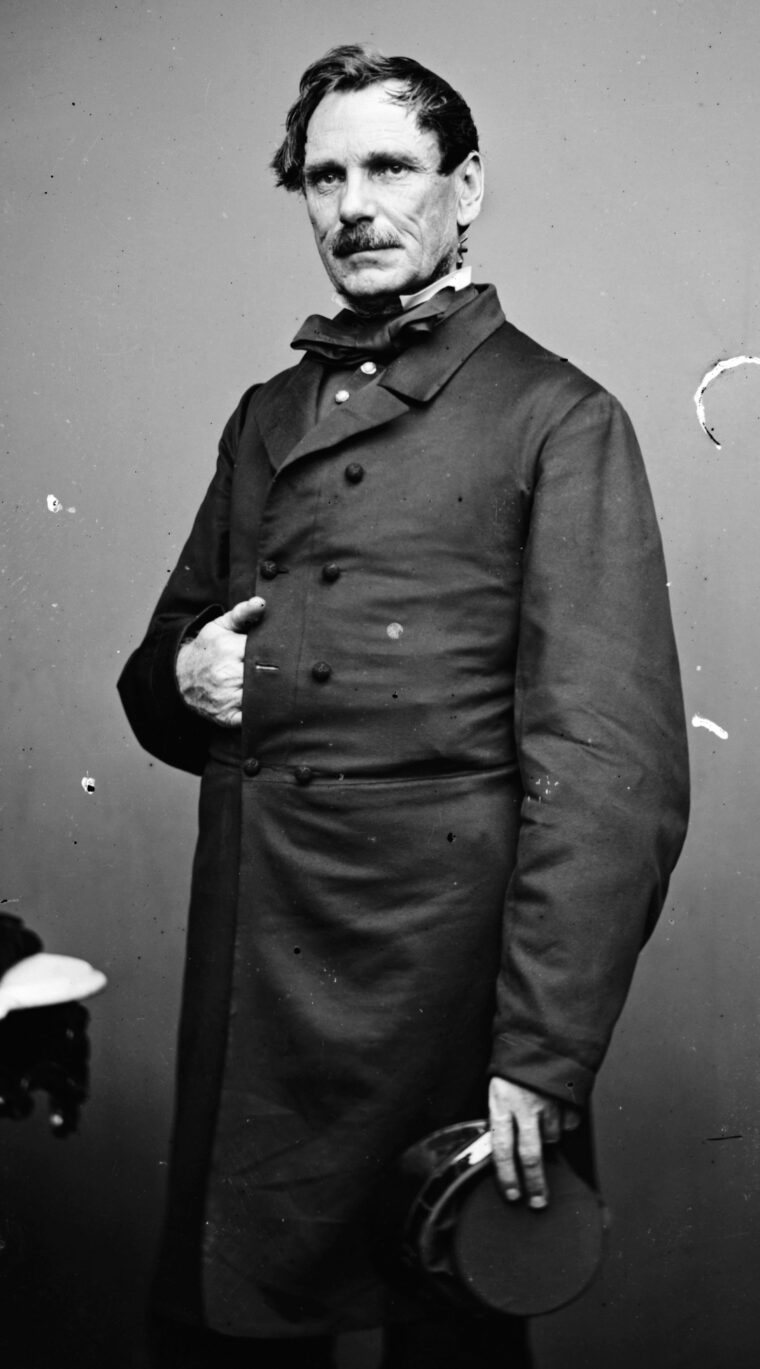

In spring 1862 Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, who had won fame for his determined stand with his brigade of Virginians atop Henry Hill at First Manassas in July 1861, had returned after the battle to the Union section of the Shenandoah Valley. Jackson suffered a tactical defeat at Kernstown on March 23 against Brig. Gen. James Shields’ Division, which at the time was part of Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks’ army of the Union Department of the Shenandoah. Shields had been wounded in the arm by an artillery fragment the previous day, and had turned over command of his division to Colonel Nathan Kimball, who had led his troops in a well-executed assault against Jackson’s line.

Kernstown, however, proved to be the only Union victory over Jackson over the course of the next six weeks. With his intimate knowledge of the geography and terrain in the Shenandoah Valley, Jackson marched his “foot cavalry,” as his fast-moving infantry was known, up and down the Valley fighting off three different Union commands.

Just two weeks after Kernstown, Jackson joined forces on May 8 with Maj. Gen. Edward “Allegheny” Johnson’s division and repulsed two Federal brigades of Maj. Gen. John C. Fremont’s forces of the Union Army’s Mountain Department at McDowell, Virginia. Fremont’s vanguard, which had been trying to invade the Shenandoah Valley by way of the Staunton Turnpike, retreated north in search of another way into the Shenandoah Valley.

After his victory at McDowell, Jackson countermarched north to strike on May 23 Colonel John Kenly’s brigade of Banks’ army defending Front Royal, Virginia. Banks, who was with the rest of his troops at Strasburg, retreated north. Jackson routed Banks’ troops two days later at Winchester. Banks, completely unnerved by the ordeal, withdrew 30 miles north across the Potomac River.

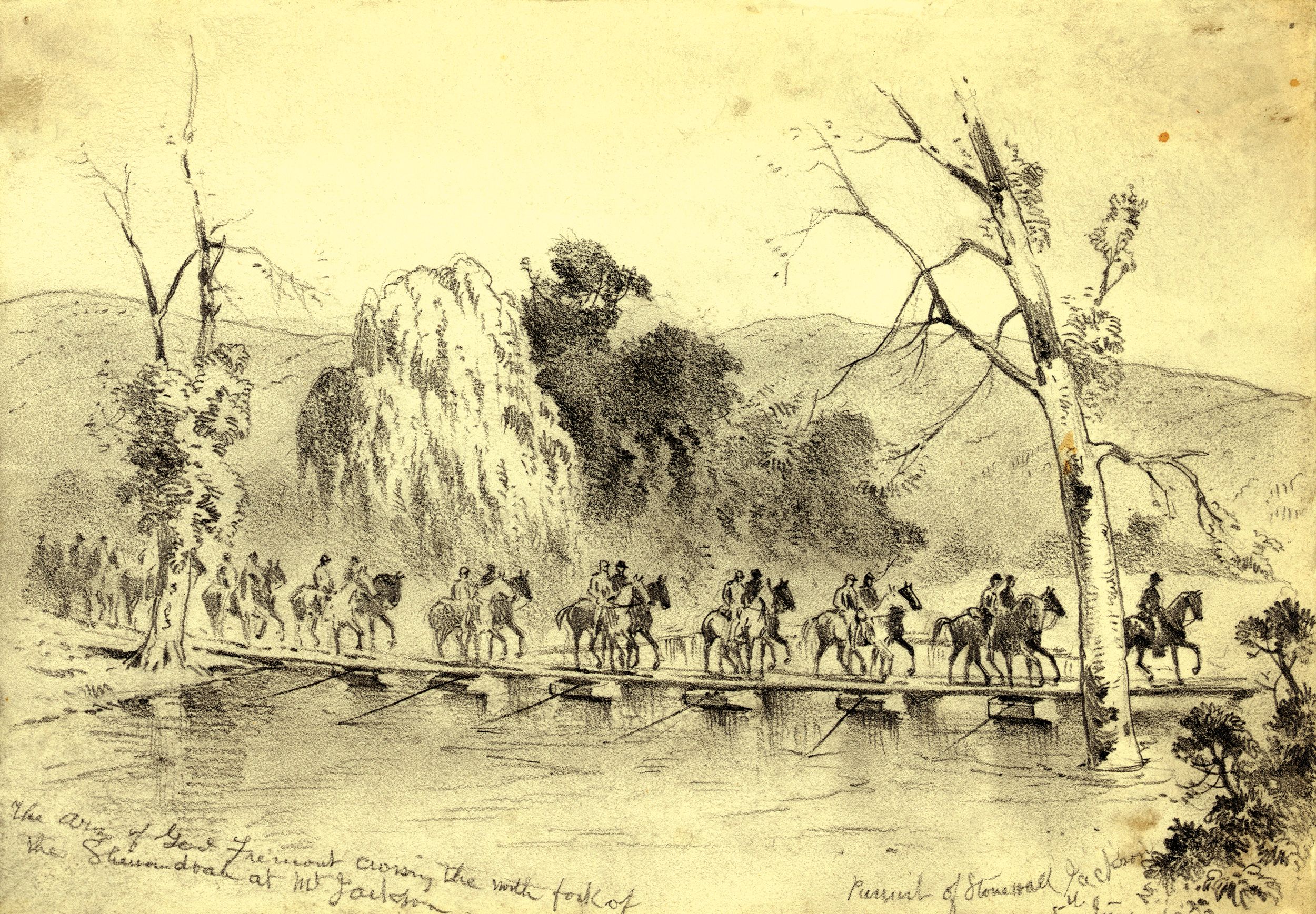

In the days that followed, Jackson withdrew south along the Valley Pike to Harrisonburg. Passing through the town on June 5 he led his army southeast to high ground north of Port Republic. By that time, Fremont had entered the main part of the Shenandoah Valley. He pursued Jackson on the west side of Massanutten Mountain, while Shields’ division advanced south on the east side through the narrower Page Valley.

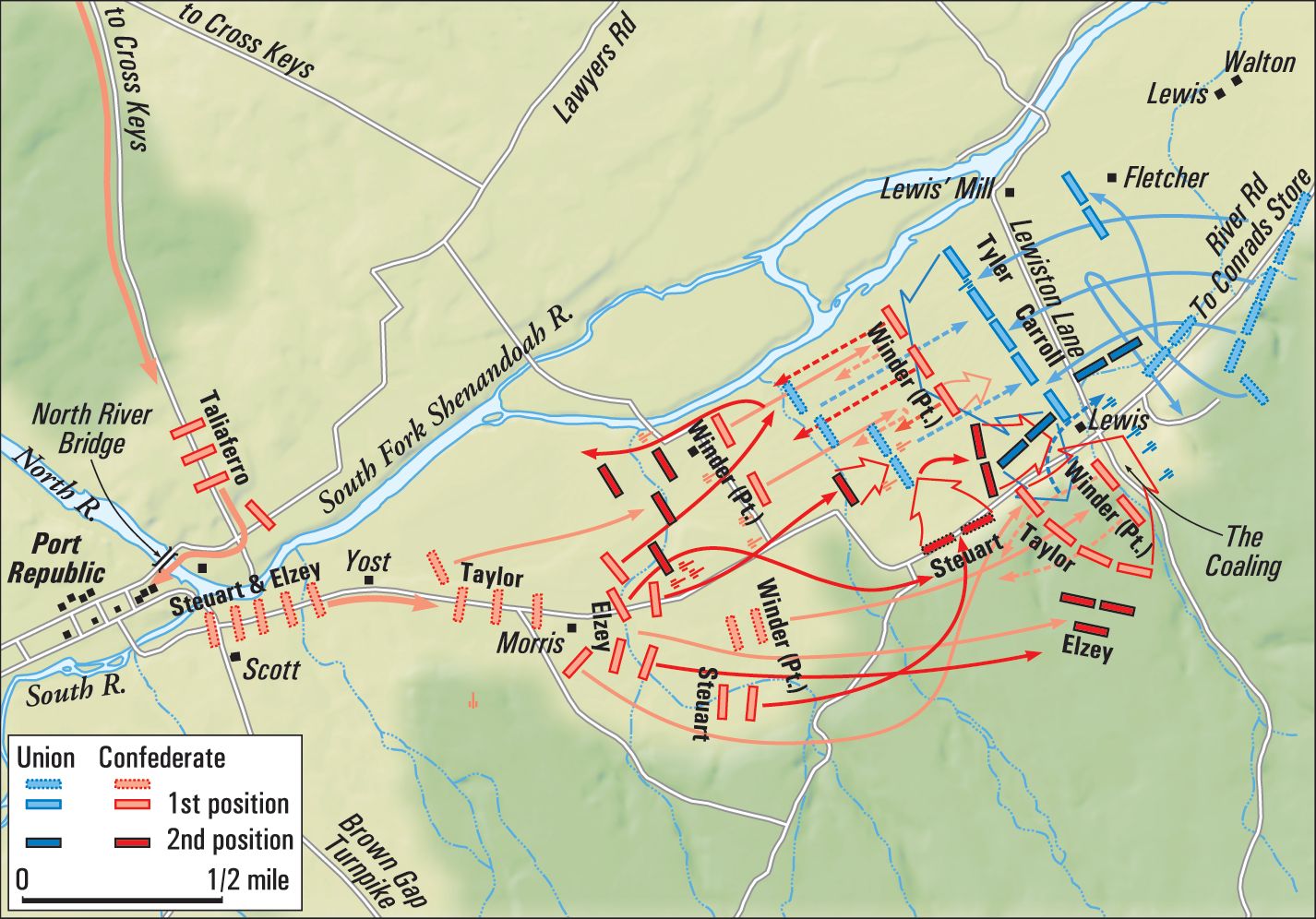

The town of Port Republic lay on the east side of the South Fork of the Shenandoah River. Port Republic was situated at the confluence of the North River and South River, which were tributaries of the South Fork. A long covered bridge spanned the North River on the west side of the town, but there was no bridge over the South River on the east side of town. There were, however, two fords that ran high from late spring rains.

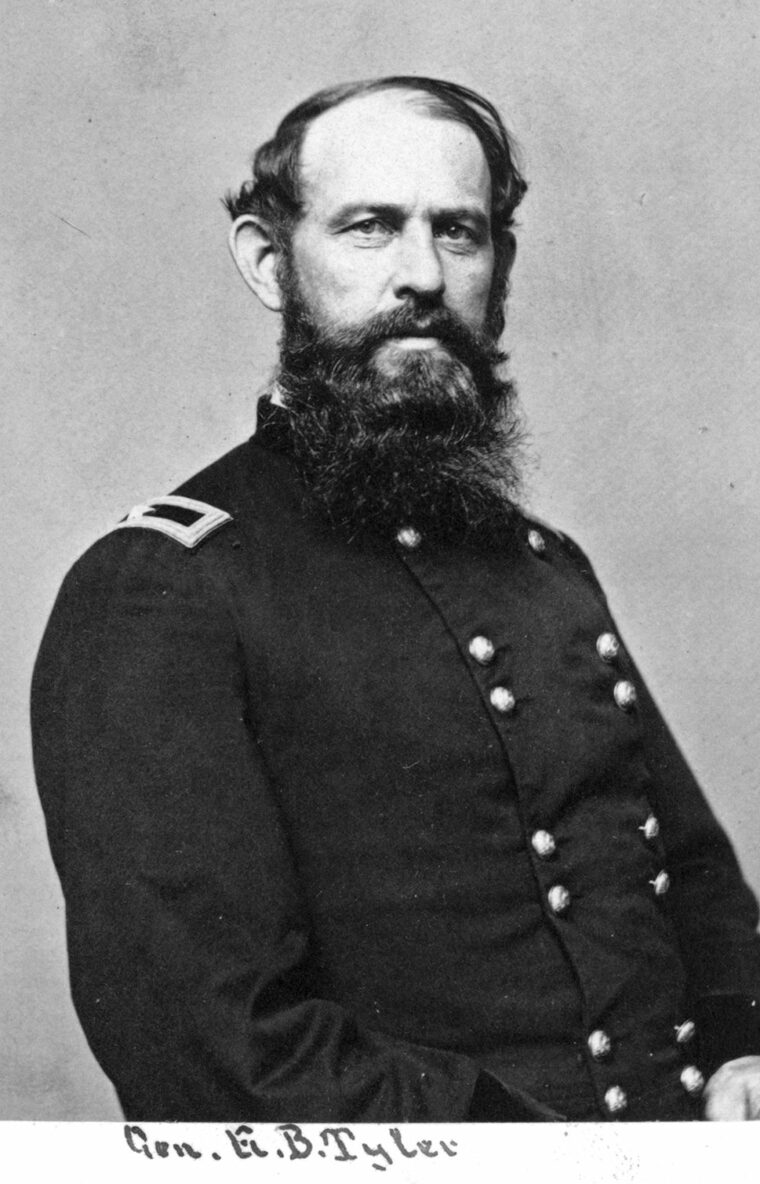

Fremont’s army, which comprised Brig. Gen. Louis Blenker’s Division and three independent brigades, reached Harrisonburg on June 6. Meanwhile, the lead elements of Shields’ division, which were commanded by Brig. Gen. Erastus Tyler, pushed south through Conrad’s Store bound for Port Republic.

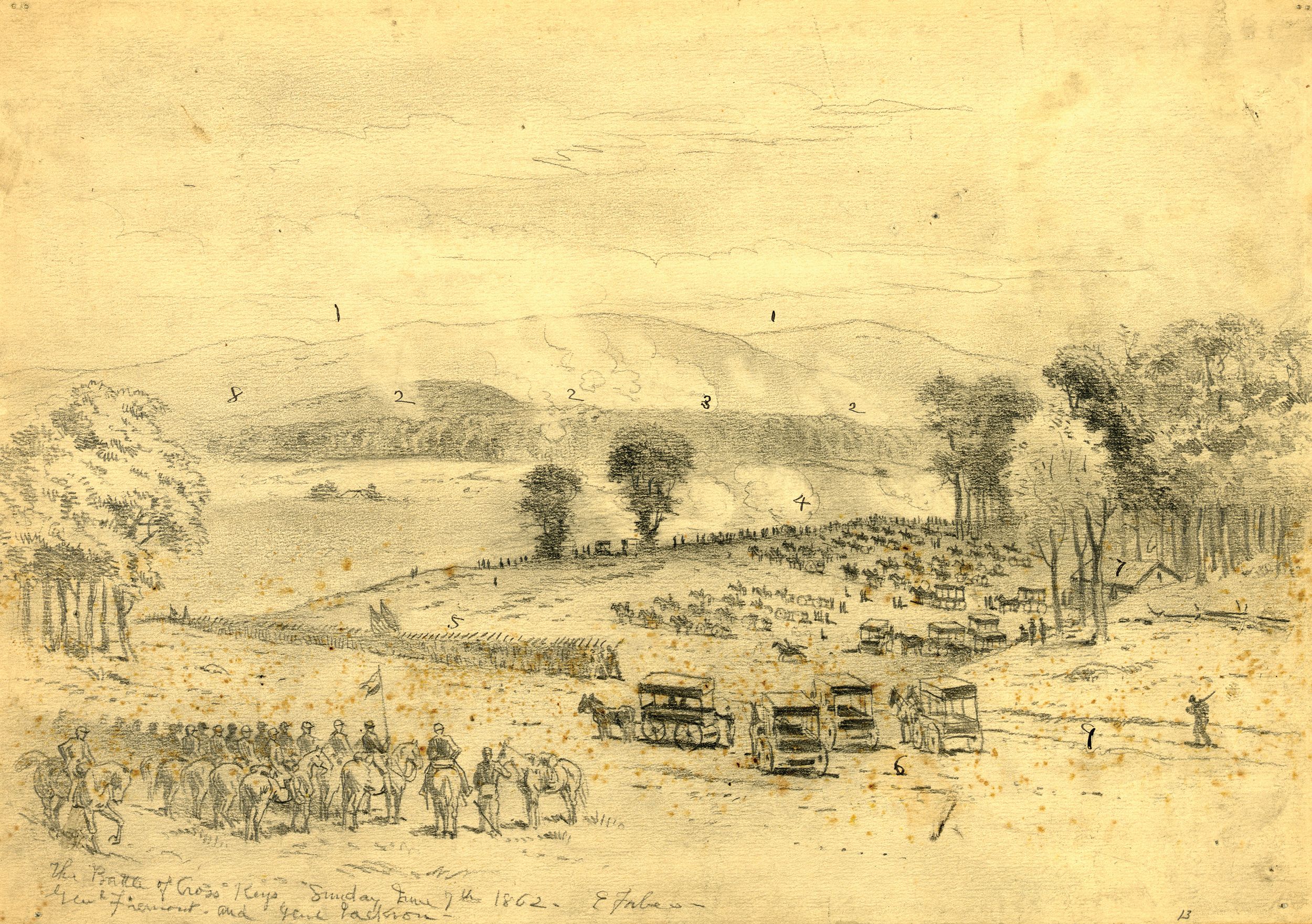

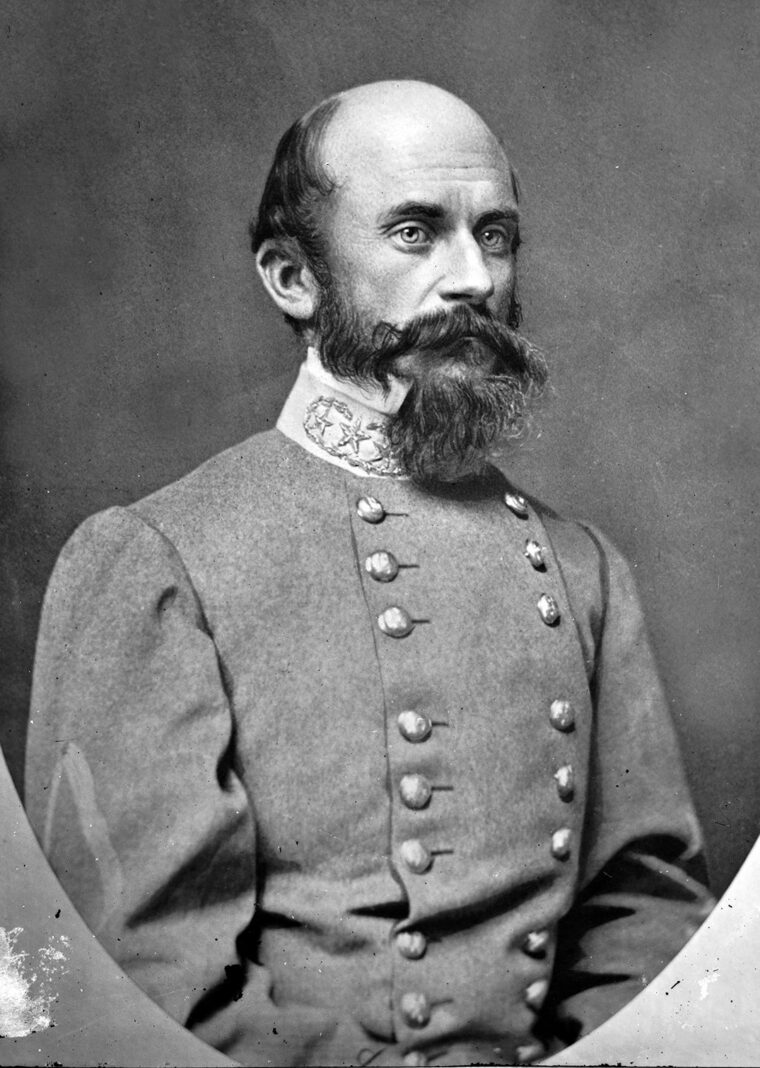

The two divisions of Jackson’s Army, his own division and one commanded by Maj. Gen. Richard S. Ewell, had bivouacked on commanding heights between Cross Keys and Port Republic. The Federal plan called for the two Union columns, Fremont’s command approaching Jackson’s position from the northwest and Shields’ command moving in from the northeast, to overwhelm Jackson’s much smaller force. Jackson ordered Ewell on June 7 to position his 5,000 troops organized into four brigades to contest Fremont’s advance. Fremont’s command, which numbered 10,500 troops, seemed to have a considerable advantage over Ewell, but the veteran Confederate division commander had the advantage of fighting on the defensive ground of his choosing.

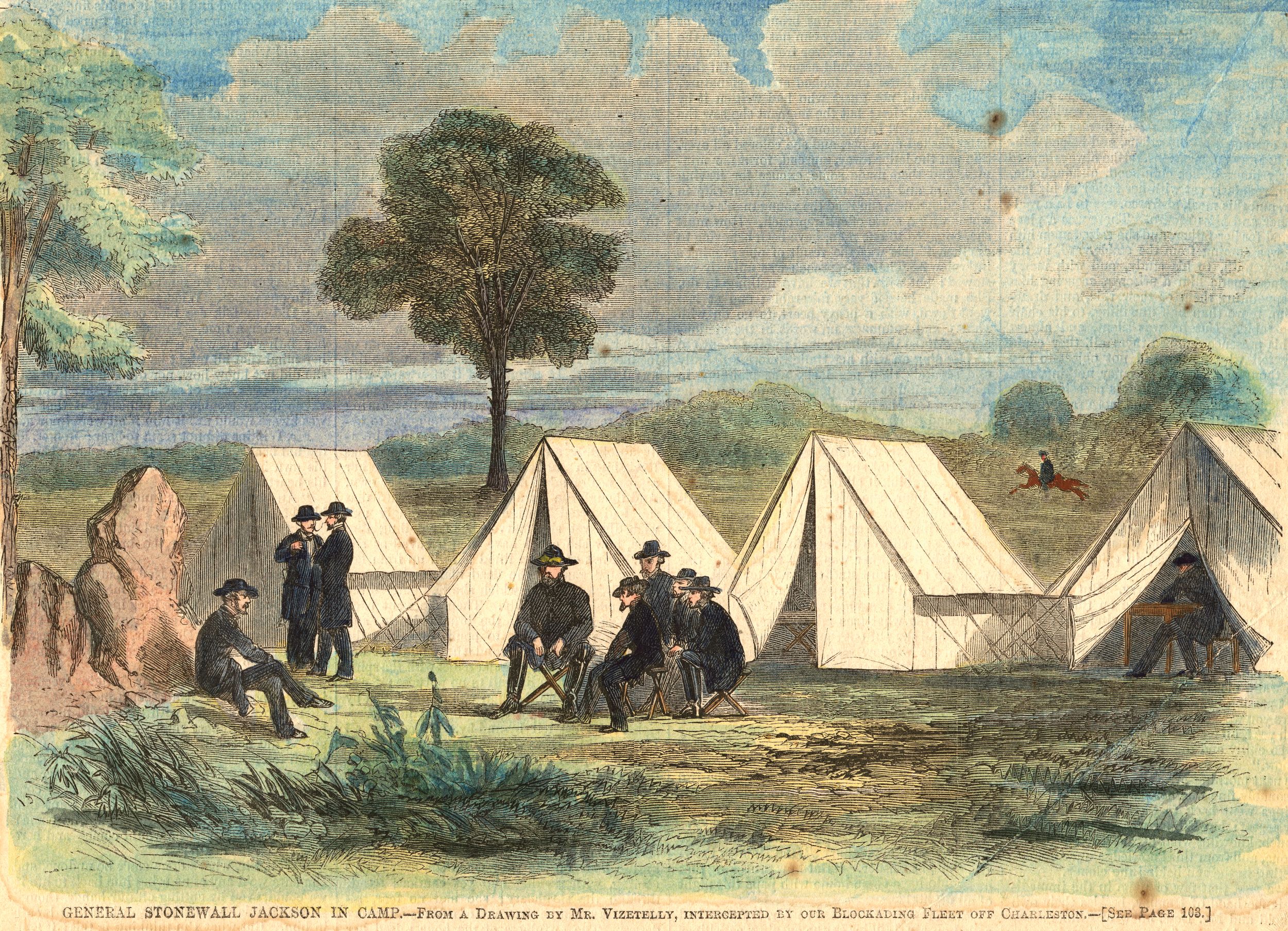

Exhausted from the rigors of the campaign, Jackson and his soldiers had an unpleasant surprise on the morning of Sunday, June 8. Old Jack anticipated a peaceful Sabbath that day. He planned to tour the army’s position on the bluffs on the north bank of the South Fork of the Shenandoah, and afterwards attend a sermon by Major Robert Dabney, who was his chief of staff and also a Presbyterian minister. Dabney asked Jackson after dawn whether he should proceed with a sermon in light of the possibility of a battle that day. “I hope you will preach to the Stonewall Brigade, and I shall attend myself; that is, if we are not disturbed by the enemy,” Jackson replied.

Six days earlier, Shields had established a strike force under Colonel Samuel S. Carroll that consisted of 150 mounted troopers, Battery L of the 1st Ohio Light Artillery, and some infantry. Shields instructed Carroll to burn the South Fork bridge at Conrad’s Store to deny its use to Jackson should he try to exit the valley by marching east to cross the Blue Ridge Mountains via Brown’s Gap or Swift Run Gap to rejoin Lee’s army.

Finding the bridge at Conrad’s Store already burned, Carroll decided to continue to Port Republic to burn the long covered bridge over the North River tributary of the South Fork. At mid-morning on June 8 Carroll’s cavalry splashed through the lower ford of the South River tributary of the South Fork of the Shenandoah River, accompanied by a section of artillery, which unlimbered and began firing at the Confederates.

Jackson, who had established his headquarters at the house of Dr. George W. Kemper in Port Republic, and the members of his staff with him scrambled to avoid capture. Jackson mounted his horse, Little Sorrel, and galloped across the covered bridge to safety. Reaching his troops on the north bank of the North Fork, he not only ordered Captain William T. Poague’s Rockbridge Artillery to fire on the Federals in the north section of Port Republic, but also grabbed the nearest regiment, which was Colonel Samuel Fulkerson’s 37th Virginia, and ordered it at the double-quick into Port Republic. “Charge right through, colonel, charge right through,” Jackson said, waving his cap above his head. He then issued orders for three of his brigades to march south to expel the Union troops from the town.

Meanwhile, Confederate pickets in Port Republic, with the support of some Confederate artillery, made a stand in the southern half of Port Republic. Caught in converging fire, the Union troops in Port Republic withdrew from the town. Almost as soon as the skirmishing in Port Republic was over, Fremont’s artillery to the northwest opened fire on Ewell’s Division deployed on a ridgeline south of the crossroads of Cross Keys.

Fremont began his attack on June 8 with a heavy artillery bombardment that wounded two of Ewell’s brigade commanders. Fremont’s infantry assault consisted of sending Brig. Gen. Louis Blenker’s brigade of German immigrants forward against the Confederate line. Brig. Gen. Isaac Trimble’s Confederate Brigade, positioned to the east, fired into Blenker’s flank, which unnerved the inexperienced Union troops. Jackson reinforced Ewell with two brigades, which was sufficient to contain another advance by the Union infantry against the Confederate left. In the halfhearted Union attack, the Union lost 684 troops compared to the Confederate loss of 288 men.

At Port Republic, on the night of June 8-9, Jackson held conferences with his subordinates. He also ordered the construction of a foot bridge over the South River because high water from recent rains precluded the crossing of infantry through the upper and lower fords on the east side of Port Republic. Jackson’s troops positioned wagons, turned upside down, in the river and placed boards across their running gear. During the crossing of the river the next day, however, the boards slipped out of position. Despite their best efforts, the Confederates moving into position to contest Shields’ advance would have to cross single file.

As Jackson prepared for the pending battle against Shields at Port Republic, he ordered Ewell to march all of his troops, except for Colonel John Patton’s brigade, to reinforce Jackson’s division. Patton would serve as the Confederate rearguard at Cross Keys.

Tyler ordered his troops to bivouac that night on the grounds of Lewiston, the Lewis family farm two miles northeast of Port Republic. For the coming battle, Tyler would have two infantry brigades, a cavalry regiment, and three artillery batteries.

The morning of June 9 dawned cool with clear skies. Jackson ordered Brig. Gen. William B. Taliaferro, the commander of the Third Brigade in his division, to recross the covered bridge over the North Fork and take up a position on the bluffs on the west bank. Jackson decided to use his First Brigade, also known as the Stonewall Brigade, to open the attack on Shields’ infantry. It took them considerable time, however, to cross the makeshift bridge over the South River.

Tyler had 3,000 infantrymen under his command that day. He began by deploying the 1,600 troops, most of whom were from his brigade, in a battle line on the open ground on the east side of the South Fork of the Shenandoah River that ran from the Lewis Mill on the South Fork to Lewiston situated alongside the main road into Port Republic.

From left to right (main road to river) the Union infantry regiments were the 1st (West) Virginia, 5th Ohio, 7th Ohio, 29th Ohio, and 7th Indiana. To the left of the Union line, on a prominent knoll where the Lewis family made charcoal, which was aptly named “the Coaling,” the Federal artillery unlimbered. Three batteries took up a position at the Coaling, which was on a western spur of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Tyler’s three artillery batteries were deployed side by side on the Coaling. Captain Joseph Clark’s Battery E of the 4th U.S. Artillery held a position on the extreme left of the Union army, Captain Lucius Robinson’s Battery L of the 1st Ohio Artillery was in the center, and Captain James Huntington’s Battery H of the 1st Ohio Artillery on the right side.

Because of a bottleneck in crossing the footbridge, the five regiments of the Stonewall Brigade did not arrive on the open ground on the east side of the South Fork at the same time. The 5th Virginia and the 27th Virginia regiments were the first to arrive. They advanced past the Baugher farm lane and went into line of battle in a field of mature wheat. The Rockbridge Artillery, led by Captain William T. Poague, moved into position to support the two infantry regiments. Poague had two rifled cannon and four smoothbore cannon. He placed his Parrott rifles between the two infantry regiments and stationed the smoothbores, which had too short a range to reach the Coaling, in a depression in the ground in the rear where they would remain until they were needed.

Union artillery at the Coaling thundered away at the Virginia infantry and artillery, hitting with lethal precision. Poague found counter battery fire to be ineffective as the smoke from the Union guns obscured their elevation and most of the Confederate artillery passed overhead.

Private Ned Moore of the Rockbridge Artillery served on the artillery crew of one of the 10-pounder Parrott guns. “We were hotly engaged [with] shells bursting around and pelting us with soft dirt as they struck the ground,” wrote Moore. Captain Joseph Carpenter, commanding the Allegheny Artillery, had four guns in his battery. He placed a two-gun section to the right of the 27th Virginia.

The Union artillery ignored the Confederate guns. The Union gunners maintained a punishing and relentless fire against the Confederate infantry. For nearly an hour, the Southern foot soldiers clung to the ground in the wheatfield, a helpless target for the Union guns. Brig. Gen. Charles S. Winder, commanding the Stonewall Brigade, ordered his two lead regiments, the 5th Virginia and 27th Virginia, to advance to a fence halfway between the opposing lines where they could exchange fire with the Union infantry arrayed against them.

When the 2nd Virginia and 4th Virginia regiments of the Stonewall Brigade arrived from Port Republic, Winder ordered these two regiments, together with another two-gun section of Carpenter’s Battery, to move through the thick woods to outflank the Federal artillery at the Coaling.

The men handling the section of artillery, however, could not force their way through the thick underbrush. They returned to the flat ground and joined the other guns of the Alleghany and Rockbridge artillery batteries in the center of the Confederate line. As the two companies of Virginia infantry drew close to their objective, Colonel James W. Allen of the 2nd Virginia ordered his two left companies, as they approached a ravine, to fire on the Union gunners. He intended the close-range fire to drive them away from their guns. The tactic failed, though, because the Union infantry guarding the guns returned the fire. The covering fire enabled the cannoneers to continue working their rifled guns.

Some of the Union gunners turned their artillery pieces towards the flanking force and fired canister at them. The deadly canister fire routed the 2nd Virginia, which fled into the woods. Allen ordered both regiments to remain in the dense thickets for the time being.

Meanwhile, the Rockbridge Artillery and the Allegheny Artillery continued to oppose courageously but fruitlessly against the Federal artillery at the Coaling. Several times enemy shells “passed between the wheels and under the axle of our gun, bursting at the trail,” wrote Moore. Carpenter’s battery had much the same experience. The crew of one of its guns eventually stopped firing altogether because they ran out of ammunition. In the face of the considerable strength of the Federal infantry, Winder ordered the 5th Virginia and 27th Virginia Infantry to fall back to Baugher lane to regroup.

In the first hour of the battle, Jackson had not gained any tactical advantage over Tyler. He knew that he must silence the Union guns on the Coaling to prevent them from shattering his line of battle. About that time, Brig. Gen. Richard Taylor’s Louisiana Tiger Brigade had arrived at the battlefront. Jackson ordered Taylor to resume the effort to outflank the Union guns at the Coaling. Jackson instructed Taylor to approach the guns on a wider arc. In this way, the Confederates just might be able to conceal their movement until they reached the ravine on the south side of the Coaling.

Because Taylor did not know the route, Jackson assigned Jedediah Hotchkiss, his topographical engineer, to serve as guide. “Jackson promptly ordered Hotchkiss to lead that command around through the forest, turn the Federal left and capture the battery on the coal hearth,” recalled Hotchkiss.

Jackson detached Colonel Harry Hays’ 7th Louisiana Infantry from Taylor’s brigade and ordered Hays to reinforce the Virginia regiments engaged against Tyler’s Union troops. Hays inserted his Louisianans between the two Virginia regiments. Another regiment, Lt. Col. Thomas S. Garnett’s 48th Virginia of Patton’s Brigade arrived on the field and Jackson placed it in reserve on the Baugher farm lane.

Union soldiers observed Taylor’s Louisianans enter the dense woods at the base of the Blue Ridge Mountains to try again to capture the guns at the Coaling. Although the gunners fired their rifled artillery at the Louisianans, the shells could not penetrate the woods

To cover Taylor’s flanking maneuver, Winder decided to charge the Union infantry, even though he was greatly outnumbered. The Confederates “moved forward with a cheer,” recalled Winder. As they advanced, though, they came under heavy fire not only from the Union infantry to their front, but also from the Union artillery firing obliquely from the Coaling.

The Confederates halted at the same post and rail fence where they had sheltered before. “The enemy opened a terrific fire upon us,” wrote Lt. Col. John Funk of the 5th Virginia, “We returned it and were exposed to a murderous cross-fire.” This crossfire came from the 7th Indiana, to their immediate front, as well as the 29th Ohio deployed in the wheatfield to their right. “My men stood firmly and poured death into their ranks with all the rapidity and good will that the position would admit,” Funk wrote.

The volleys from the 5th Virginia took a toll on the Federal troops, who soon ran out of ammunition but remained staunchly in their ranks. The 29th Ohio to the left of the 7th Indiana also suffered severely. Meanwhile, the 7th Ohio received fire from the right companies of the 7th Louisiana and the left companies of the 27th Virginia.

Hays’ 7th Louisiana moved forward on the right of the 5th Virginia. They advanced to the fence in the middle of the wheatfield. Some of the more aggressive soldiers climbed over the fence. They were met every step of the way by stinging volleys from the Union infantry. The Louisianians also suffered from the artillery at the Coaling.

Colonel Andrew J. Grigsby’s 27th Virginia aimed for the same fence as the other two regiments, closing on the right of the 7th Louisiana. Shells from the Coaling immediately found their marks in the regiment. “The ranks were considerably thinned,” wrote Grigsby. The Virginians advanced past the fence with little opposition from the Union infantry, which concentrated most of its fire on the two left regiments of the Confederate battle line.

Some of the 27th’s men took up positions behind the outbuildings and in the orchard at Lewiston. Grigsby ordered the rest to drop back on a line with the 7th Louisiana along the fence. They remained at that location for a while where they came “under a perfect shower of balls,” wrote Grigsby.

Winder pushed Confederate artillery forward to support the three Confederate regiments behind the fence that were hotly engaged with the Union forces in front of them. A section of Carpenter’s Battery unlimbered 30 yards behind the 27th Virginia, on a small knoll. In addition, a section of guns from Captain Charles Raines’ Lee Battery of Ewell’s Division arrived on the field and Winder integrated the guns into his line.

At the same time, Winder instructed Poague to advance one of his rifled guns and put it into action near Carpenter’s guns. Poague directed his fire at the Union artillery at the Coaling. Meanwhile, Winder brought up Poague’s four smoothbore guns, but they soon had to retire when they ran out of ammunition.

The three Confederate infantry regiments held their advanced position at the midfield fence for as long as they could. Though some of the men, having had enough of the fight against superior numbers of Union infantry, began to creep towards the rear. Soon after, the entire line gave way. It had become demoralized and would have to be rallied before it could return to the fight. Of the 400 men of the 7th Louisiana that entered the battle, 162 were either killed or wounded. The 5th Virginia on the left of the line retired next, but Funk rallied his men behind the Baugher farm lane.

The 27th Virginia was the last to abandon its forward position. When the Union infantry saw the Confederates abandoning the fence, they counterattacked. “The order was given, and with a yell the entire line poured its leaden hail into the gray-clad columns,” wrote Private Secheverell of the 29th Ohio Infantry, “producing fearful slaughter, and following with a charge so impetuous that they were forced to retire from their secure position behind the fence.”

When the Federals reached the midfield fence, their officers told them to lie down behind it and await the replenishment of their ammunition. The regimental commanders dispatched details of soldiers to go to the rear and find additional cartridges. Most of the 29th Ohio also stopped at the fence, though a few of its soldiers went a short distance past it. Private Allen Mason of Company C of the 29th Ohio captured the 7th Louisiana’s flag.

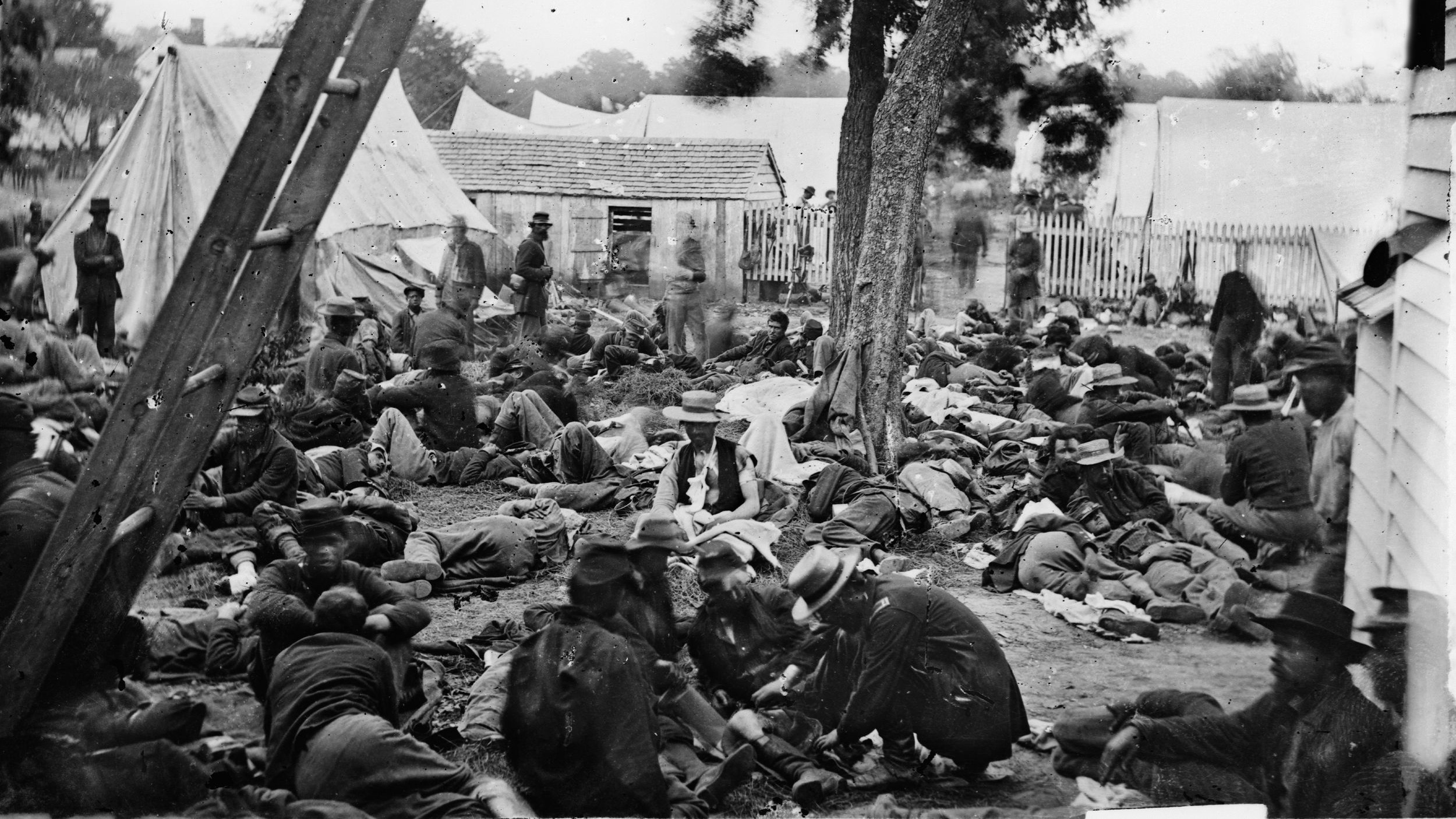

The 5th Ohio and 7th Ohio charged beyond the fence into the wheatfield. The 1st (West) Virginia advanced from Lewiston, leaving the Confederates holding the outbuildings and orchard behind them. The advancing Union troops followed on the left of the 5th Ohio taking full advantage of its success against the Confederates. Casualties on both sides grew as the Union soldiers fired on the retreating Confederates who paused in their withdrawal to fire back. Tyler noted in his battle report that the Confederates “suffered severely.” They were not alone, though, for the Federal soldiers also endured their fair share of casualties. A steady stream of wounded Union troops shuffled to the rear as the battle wore on.

Six fresh Confederate regiments, the equivalent of more than a brigade, arrived at this stage of the battle. Ewell led them forward with the confidence of a seasoned commander. The 44th, 52nd, and 58th Virginia of Brig. Gen. George H. Steuart’s Second Brigade of Ewell’s Division came up first. They were commanded by Colonel William C. Scott since Steuart had been severely wounded in the shoulder by an artillery fragment at Cross Keys.

Brigadier General Arnold Elzey, commander of the Fourth brigade of Ewell’s Division, had also been wounded at Cross Keys, so Colonel James Walker of the 13th Virginia Infantry had taken over command of the brigade. Walker led the 13th Virginia, 25th Virginia, and 31st Virginia forward into the action.

The soldiers of the 52nd Virginia arrived first. When they reached the Baugher farm lane they encountered the frontline units, consisting of the two regiments of Winder’s Stonewall Brigade and the 7th Louisiana, retiring in confusion. Skinner took his men into action on the Confederate left flank. The 52nd surged forward through the field where the Union fire was “cutting off the heads of the wheat,” Skinner recalled.

A group of Union troops had taken cover in a thicket along the banks of a stream known as Little Deep Run that crossed the Baugher farm to empty into the South Fork of the Shenandoah River. The unexpected enemy fire from a concealed position disrupted the advance of the 52nd Virginia, and they fell back to the Baugher lane to regroup having suffered 84 casualties. Ewell personally led the rest of Steuart’s Brigade, the 44th and 58th Virginia, into the woods south of the Coaling.

Walker sent the 31st Virginia into action against the Union infantry on the plain, and then led the 13th Virginia and 25th Virginia off to the right in an effort to reinforce Taylor in his attack on the Coaling. His Virginians, however, got bogged down in the tangled underbrush of the woods south of the Coaling and never went into action against the Union guns.

The 25th and 31st Virginia advanced to aid Winder. Colonel John S. Hoffman, who commanded the 31st regiment, led his men into position on Winder’s right. At the time, Winder was trying desperately to rally his troops. As they came on line, the soldiers of the 31st Virginia had to endure the same blistering enemy fire that had dislodged the Stonewall Brigade.

When Hoffman’s men entered the wheatfield, they found themselves alone. They wriggled forward on their stomachs, rising to shoot, and then dropping again to load and continue to move forward. Five color bearers went down, and their lieutenant told his men to let the colors lie.

Their advance bogged down under a Union counterattack. They suffered a destructive fire both from the front and from the side. They sprawled on the ground in the wheatfield as the minie balls sliced through the grain. The 31st Virginia suffered 34 killed and 83 wounded in the battle. The number of killed was more than any other Confederate regiment at Port Republic.

The storm of Union musket fire drove them all of the way back to the Baugher farm lane.

The short-lived stand by the soldiers of the 31st Virginia, which was aided by the advance of the 25th and 52nd Virginia regiments, gave time for Winder to rally his regiments. It also bought more time for Taylor’s Louisianans to reach the Coaling.

Ewell watched as Federal forces pursued the Confederates across the flatland. He decided to strike the Union troops in their exposed left flank, which he hoped would stop their advance. His troops followed a road into a wood on the Union left that would put them in position to strike the Coaling. He formed the two regiments into a line of battle perpendicular to the Union line with the 58th Virginia on the left and the 44th Virginia on the right.

Ewell ordered the fences on both sides of the road torn down, but he purposely left a third fence nearby in the cultivated fields standing in order that his men could take shelter behind it. He then ordered his troops forward. They advanced screaming the ear-splitting Rebel Yell. “[Our men were] yelling more to keep our courage up than to frighten the enemy,” wrote Adjutant C.C. Wight of the 58th Virginia.

When the Union gunners atop the Coaling observed the new threat, they turned their guns on Ewell’s soldiers. When the Confederates reached the fence they were intended to take up a position behind, they kept on going in the direction of the left flank of the 5th Ohio and 7th Ohio. When they drew close to the enemy, the 48th Virginia and 58th Virginia fired a crashing volley at the Buckeyes. The Buckeyes recoiled from the heavy fire.

The Virginians’ ranks had become disordered from crossing the fence. When the momentum of their charge dissipated, they halted in the field under a murderous hail of return fire from the Federal infantry, as well as artillery fire from Union guns in the Coaling. The Virginians could not withstand the punishment, however, and eventually returned to the shelter of the woods.

Confederate artillery aided greatly in Winder’s defense at the plain. Most of the artillery directed their fire at the Federal infantry because it was useless to fire at the Coaling. They had been fighting since the beginning of the battle and one of the pieces of the Rockbridge Artillery ran out of ammunition. All four of Captain Poague’s smoothbores went into action on Winder’s orders. When the Southern line collapsed, three of the smoothbores withdrew. The other smoothbore, which was commanded by Lieutenant James Cole Davis, was being swept back with the rest when Winder ordered him to halt and fire on an advancing Union column.

At that very moment, Ewell led his attack from the woods. Davis stopped his retreat and turned his gun on the enemy and fired on them. The artillery fire, coupled with the simultaneous attack of Ewell’s Virginians on the Federal flank, temporarily stopped the Union advance. “No act of a subordinate that I have seen during the Valley campaign has so excited my admiration for its coolness, judgment and bravery.” Ewell wrote in his battle report. Even though he could not identify the artillery lieutenant by name, he nevertheless acknowledged his courage on the field of battle.

Davis suffered for his bravery, however, as he was severely wounded in his side. The 5th Ohio, which was the regiment whose advance was checked by Davis, captured the piece. The Confederate gun crew had to abandon their piece when Union infantry swarmed around it. Private John Gray of the 5th Ohio quickly gathered a team of unwounded horses and dragged the cannon to the rear.

Ewell’s charge and the Confederate artillery fire had curbed the Union advance. Their valorous action gave Winder time to stitch together a new line anchored on the 7th Louisiana and 5th Virginia. The 27th Virginia had become too disrupted to rally.

The Federal infantry advance never resumed. The Confederates battling on the flatland believed at that point that the battle was lost. The men of the 4th Virginia, peering out of the densely wooded ground on the hillside, shared this feeling. Some even believed that their beloved commander Jackson had once again met his match against Shields’ command, as it had at Kernstown.

The best chance for a Confederate victory lay in silencing the Union guns at the Coaling. The 1,700 troops of Taylor’s Louisiana Tiger Brigade had reached the Deep Run ravine that separated the Coaling from the woods to the south. He planned a flanking movement on the Coaling, but had to change his plans when a dispatch arrived from Winder requesting an immediate attack to relieve pressure on the Virginians engaged against Tyler’s Midwesterners. Winder sent Taylor a message urging him to make an immediate attack upon the Federal position and the battery across the ravine.

The Louisianans knew the outcome of the battle lay in their hands. They greatly outnumbered the defenders at the Coaling, but they would have to endure canister fire at close range to capture the commanding ground. Through much difficulty, the Tigers formed a line of battle in the woods. From left to right Taylor’s line of battle was the 6th Louisiana, Major Chatham Roberdeau Wheat’s Battalion, the 9th Louisiana, and the 8th Louisiana.

The Louisianans plunged down the steep slope into the ravine and up the other side. They swarmed over the Union guns. The Union artillerists milled around their guns in a disorganized fashion. Some of the cannoneers got off a final round of canister at point-blank range, and the Union infantry supporting the guns fired a final volley. The fighting then became hand-to-hand. The Union gunners no longer had any opportunity to load and fire their smoking guns. While bayonets were rarely used in battle during the conflict, witnesses recalled bayonet fighting. “Many fell from bayonet wounds,” wrote Taylor.

Artillerists used their rammers and extractors as clubs. Even Union musicians joined the fray using their instruments to bash Confederates. The men of the 66th Ohio, who were supporting the Union artillery, fell back under the vicious Confederate assault. Taylor’s Louisianans overlapped the Unions on both flanks. Unless Tyler rushed reinforcements to the position immediately, it was unlikely that it could be held.

Confederate officers ordered their men to kill the horses of the artillery battery so that the guns could not be limbered or dragged from the field. Major Chatham Roberdeau Wheat, the commander of Wheat’s Battalion of Louisiana Tigers, fired his pistol at some of the horses. After he had exhausted his ammunition, he drew his Bowie knife and began slashing the throats of some of the horses. The Confederates emerged victorious from the seesaw fighting for the Federal guns atop the Coaling. Their victory turned the tide of battle in favor of Jackson’s army.

The broken Federal infantry reformed and countercharged the Confederates in a bid to retake the Coaling. The 5th and 7th Ohio advanced across the flatland meeting resistance on the way from Confederates in protected positions on the grounds of Lewiston. When the Union reinforcements arrived, some of the Louisianans tried to fight back, but the majority retreated across the ravine to the edge of the woods. Union artilleryman Captain James Huntington of Battery H, 1st Ohio Artillery, saved his right gun, leaving the limber and caisson behind.

Taylor’s Louisianans were not idle. They laid down a blistering fire with their rifled-muskets to prevent the Union army from strengthening its hold on the key position. The fighting on the flatland along the river paused as every eye on both sides of the field turned toward the Coaling to observe the struggle for the guns. Winder directed his troops to direct volleys of fire uphill towards the Federals struggling to defend the Coaling.

Taylor rallied his Louisianans once again. They swept down into the ravine and uphill towards the Coaling yet again. When some Union infantry poured a fire into their right flank, Taylor directed two of his right companies to eliminate the threat. They climbed up to a higher elevation and poured a hot fire into the Union infantry forcing them to withdraw.

The Louisianans returned with their usual fury. “They reach the guns again, and again men shoot, stab, cut, hack,” Taylor wrote. The Louisianans forced the Union soldiers back a second time and retook the Coaling. This second attack cost the Tigers as many men as the first. The slow destruction of Taylor’s officer corps brought down the cohesion and combat effectiveness of the enlisted men. The men fought individually, and some turned the captured guns against the Union soldiers.

The Union troops guarding the guns were not finished yet, though. They reformed in the woods north of the Coaling and in the plains below to launch another counterattack. The Federals drove the Confederates from the Coaling a second time after which point there was brief lull in the struggle for the guns.

Jackson ordered Taylor to assault the guns a third time. At that point, Ewell arrived on the field with reinforcements just in time to lend much needed strength to the Confederates’ fresh attack on the Union guns at the Coaling. The Louisianans once again came on screeching the Rebel Yell. They surged across the ravine and captured the guns for good.

The third assault “was a desperate rally,” wrote Taylor, against what he described as an overwhelming enemy force. Even the Southern drummer boys took part in the attack. The Confederates took possession of a field of carnage with dead and dying horses and soldiers, as well as many badly wounded soldiers. Federals and Confederates alike lay piled in heaps with the blood of men and horses covering the ground, recalled Private Sam Buck of the 15th Virginia.

The Federals on the flat land along the river knew that to continue the fight was useless since the Confederates had captured the commanding ground. They slowly retreated north. A short time earlier, Jackson had sent orders to Brig. Gen. Isaac Trimble to bring the rest of the Confederate troops across the covered bridge over the North River and burn it in order to prevent Fremont’s troops from using it.

Trimble marched all of the troops across the bridge, but he waited until the Confederates had driven Tyler’s force from the battlefield at Port Republic before torching the bridge. Jackson sent some of his troops in pursuit of Tyler, who withdrew north to reunite with the rest of Shields’ command. The Confederates pursued the retreating Union troops for four miles and then returned to Port Republic. Confederate losses at Port Republic totaled 816 men, while the Union suffered 1,002 casualties.

Although the battle was a close fought one, Jackson prevailed over Tyler; in so doing, he avenged the tactical defeat by the forces of Shield’s command at Kernstown 11 weeks earlier. Jackson led his two divisions out of the Shenandoah Valley on June 17. They were bound for Richmond where Jackson reinforced General Robert E. Lee, the newly appointed commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, in the Peninsula Campaign against Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. Confederate President Jefferson Davis had given Lee command of the army on June 1 following the wounding of General Joseph Johnston the previous day in the clash at Seven Pines.

The victory at Port Republic capped a magnificent campaign in which Jackson had disrupted the Union military effort in the East and forced Washington to funnel troops from various commands into the Shenandoah Valley to contain Jackson. As an integral part of that victorious campaign, the fighting at Port Republic continues to fascinate students of the Valley Campaign of 1862.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments