By Robert F. Dorr and Fred L. Borch

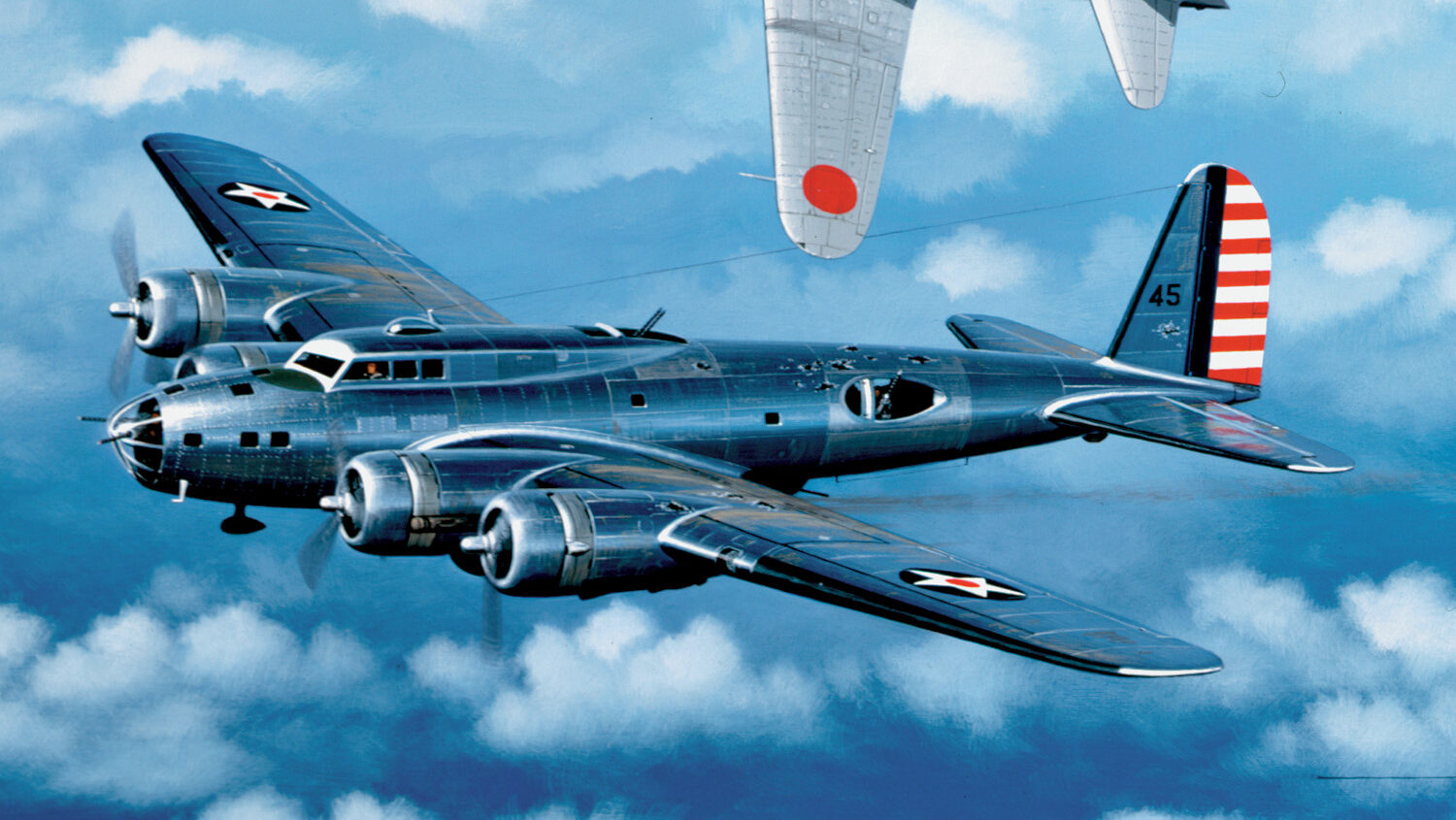

Marine aviators of Fighter Squadron 211, or VMF-211, looked up in frustration as Japanese war planes thronged over Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The attack took them completely by surprise. Not one of their portly Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat fighters was able to get into the air to battle Japan’s vaunted Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters.

Captain Robert E. Galer, at Ewa Air Station that morning, looked up and shook his head vigorously at the sight of the red “meatballs” painted on the wings of the Japanese planes. At Ewa, four Marines were killed and 33 aircraft were torched. The contingent of squadron VMF-211 that was not at sea aboard the aircraft carrier USS Lexington (CV 2) that day lost nine Wildcats on the ground. It was the last time Marine Wildcat pilots were caught flat-footed.

The Wildcat had become the standard Navy and Marine fighter soon after Grumman engineer and pilot Robert L. Hall took the F4F-2 prototype aloft for its first flight on September 2, 1937. The F4F-2 was not really the second version of Grumman’s fourth fighter, as its designation suggested. It was a new aircraft, powered by a 1,050-horsepower Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp radial engine, with a maximum speed of 385 miles per hour, and armed with six .50-caliber machine guns.

The Wildcat’s Navy service has become better known than its Marine Corps duty. The Wildcat was the fighter piloted by Lieutenant Edward “Butch” O’Hare, of Navy Squadron VF-42 aboard the USS Lexington, who was credited with shooting down five Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bombers in five minutes near Rabaul in a furious dogfight on February 20, 1942. O’Hare was awarded the Medal of Honor.

But long before that happened, Marines were wringing out the Wildcat when the Japanese attacked the American outpost at Wake Island. VMF-211 followed up its Pearl Harbor losses by losing seven more Wildcats on the ground at Wake on December 8, 1941, but the squadron’s pilots also scored victories. First Lieutenant David S. Kliever and Technical Sergeant William Hamilton of VMF-211, flying from Wake, shot down a pair of twin-engine Mitsubishi G3M2 Type 96 “Nell” bombers on December 9. Captain Henry T. “Hammerin’ Hank” Elrod, also of VMF-211 and soon to be briefly the most famous Marine pilot in the world, also shot down a Japanese aircraft that day.

During the heated defense of Wake, Marines kept their Wildcats flying by cannibalizing wrecked aircraft, improvising tools, and hand making some parts. When the Japanese attempted their first landings on the morning of December 11, 1941, four Wildcats attacked the invasion force with 100-pound bombs and .50-caliber machine-gun fire. That was when Elrod achieved a direct hit on the Japanese destroyer Kisaragi, apparently sinking the ship and forcing the Japanese invasion fleet to retire temporarily.

On December 21, 1941, the Japanese returned, reinforced by carrier aircraft. Just two Wildcats survived to attack a 39-plane raid from the Japanese carriers Soryu and Hiryu. Zeros quickly shot down one Wildcat, but the second shot down two of the raiders before its pilot, Captain Herb Frueler, was wounded. Frueler struggled home and crash-landed, wrecking Wake’s last Wildcat.

When “Hammerin’ Hank” Elrod no longer had a Wildcat to fly, the 36-year-old captain demonstrated that Marines are, first and foremost, riflemen. Elrod assumed command of a flank of the line set up to make a last stand against the Japanese landing. He conducted a spirited defense, enabling his fellow Marines to repulse waves of attacking Japanese and to provide covering fire for unarmed ammunition carriers. Elrod seized a discarded automatic weapon, gave his own firearm to one of his men, and fought on—losing his life. He received a posthumous Medal of Honor.

In the air battles of the early Pacific War, Marines found themselves equally outfought. The Wildcat was simply outperformed in aerial duels with the vaunted Zero at Wake, Coral Sea, and Midway. The Wildcat was the Marines’ standard fighter amid the heat, stench, and muck at Henderson Field on Guadalcanal.

The 1st Marine Division captured the nearly completed airfield on August 7, 1942. From its unpaved strip, Marine aviators did some of the toughest flying of the war. To the pilot of an F4F Wildcat taxiing at Henderson in a torrential downpour, struggling through geysers of water and mud, the list of enemies included bad weather, corrosion, primitive conditions, and even tropical disease. It was hard to stay ready to repel the next wave of Japanese bombers when you had to pluck leeches from your skin with a bayonet, or run to the head to disgorge the foul water and poor food.

On August 20, 1942, Major John L. Smith’s VMF-223, the “Rainbow” Squadron, launched from the escort carrier USS Long Island (CVE 1), and landed at Henderson to set up shop. On August 24, accompanied by five Army Bell

P-400 Airacobras, Smith intercepted a Japanese flight of 15 bombers and 12 fighters. VMF-223 pilots shot down 10 bombers and six fighters, with Captain Marion Carl scoring three of the kills. Carl became the first Marine air ace of the war, Smith the second Marine Wildcat pilot to rate the Medal of Honor. Another Marine, Captain Joe Foss, racked up 26 aerial victories and also received the nation’s highest award.

So did Major (later Brig. Gen.) Robert E. Galer, the Pearl Harbor survivor who now commanded squadron VMF-224. Galer scored 13 aerial victories and waged a point-blank campaign against the Japanese for 29 days.

At Guadalcanal, Japanese bombers typically approached 26 at a time in V formation. Wildcat pilots sought to avoid Zeros and get at the bombers. Their hit-and-run tactics forced the Zero pilots to use precious fuel. After dogfighting began, the Americans learned the importance of teamwork, finding that reliance on one’s wingman was crucial and that no lone wolf survived for long.

The Wildcat was no Zero. The Japanese fighter was light and fast and had cannon as well as machine guns. The American fighter was sturdier and gave the pilot a much better chance of surviving if he was hit. As they gained experience, Marines learned how to coax greater maneuverability from their Wildcats. They learned how to make better gunnery compensate for the lesser killing power of their guns.

In the same class as Carl, Smith, Foss, and Galer, one of the great Wildcat pilots at Guadalcanal was Lt. Col. Harold W. “Indian Joe” Bauer. Bauer was a U.S. Naval Academy graduate who commanded Marine Fighter Squadron VMF-212, the “Devil Cats.” He shot down 11 Japanese aircraft and paid the highest price to win the nation’s highest award.

When Marines landed on Guadalcanal and seized Henderson Field in the first U.S. offensive action of the war, Bauer’s squadron was at Efate, New Hebrides, preparing to enter the fray. Bauer left them there and flew down to Guadalcanal to inspect the airfield, which was under constant Japanese air attack. On September 27, 1942, he borrowed a Wildcat from friend and rival Carl, took off to intercept approaching Japanese bombers, and shot one down.

Also during his so-called inspection visit, Bauer shot down four Japanese Zero fighters on October 3, 1942. His squadron had not reached the combat zone yet, and he was already an ace.

The Japanese mounted a major effort to dislodge the Marines in a furious counterattack. It happened just when Bauer was bringing his “Devil Cats” to Guadalcanal on October 8, 1942. Bauer found a Japanese air raid under way. In the waters off the great island, Japanese Aichi D3A “Val” dive-bombers were swarming down on the USS McFarland (AVD 14), an ex-destroyer, now a freighter, carrying aviation fuel and ammunition that were desperately needed on Guadalcanal.

Bauer pounced on the dive-bombers as they withdrew. Although low on fuel, he gave chase. A 55-gallon external fuel tank was stuck beneath the right wing of his Wildcat, reducing his airspeed and maneuverability. Still, Bauer dived from 3,000 to 200 feet and closed on the Japanese warplanes. He had superb targets and a full load of ammunition. Bauer shoved throttle, mixture, and prop controls to the firewall, overtook the dive-bombers from behind, and began squeezing off bursts. In a matter of minutes, he sent three Vals falling in flames into the sea near Savo Island.

On the day of that fight, Bauer was placed in charge of all fighter operations on Guadalcanal. On November 14, 1942, he took off to investigate a Japanese convoy of 11 troop transports escorted by 11 destroyers bearing down on Guadalcanal—the big heft behind the enemy’s planned counteroffensive.

Bauer attacked the ships and was met by Japanese fighters. He battled Zeros and shot two down. But bullets ripped into his Wildcat. Unable to maintain control of the F4F, he parachuted into the sea.

Aloft with Bauer in the midst of that slugfest were Foss and Major Joe Renner. Foss and Renner raced back to Guadalcanal, traded their Wildcats for a J2F Duck amphibian, and took off to attempt to locate Bauer at sea. Darkness closed in before they could complete the search. No one ever saw Bauer again. A recommendation for a Medal of Honor for him was approved in May 1943.

Wildcat pilots fought on, often caught up in a love-hate relationship with an aircraft that was a kind of ongoing good news, bad news story. “A fire hydrant with wings,” said former Captain Thomas M. “Tommy” Tomlinson. “The barrel-like, mid-wing configuration of the Wildcat gave it a certain raffish appearance.”

Said Tomlinson: “It was anything but a beauty, and it didn’t handle well in the wrong hands. For takeoff, the Wildcat required especially careful handling, because the fuselage blanked the rudder, and it had a nasty tendency to veer to port. The tail wheel had to be locked and checked and it didn’t perform well in a crosswind. Until you got the tail off the ground, you had to concentrate on stick and throttle every second. In short, being a pilot of the F4F Wildcat was a full-time job.”

Tomlinson said that in a dogfight with a Zero, the Wildcat could not maneuver the way the Zero could. But, he added, “The Wildcat was a solid, stable gun platform. Once you got past the awkward arrangement of some of the instruments and controls, the Wildcat was probably about as good an airplane as you were going to get in the early days of the war. If you mastered it, you could probably stand a chance of beating that Zero, but the real answer was a newer and better fighting machine.”

Tomlinson was at Ewa and Guadalcanal as a member of Fighter Squadron VMF-214, the “Swashbucklers.” He is quick to take affront at anyone who thinks the VMF-214 terminology belongs to the “Black Sheep,” the famous Vought F4U Corsair squadron later in the war that was led by the ambitious Gregory “Pappy” Boyington. “I was in VMF-214 when it began, at Henderson Field on Guadalcanal, living in a coconut grove, with an outdoor head and not much in the way of amenities,” Tomlinson said.

As Tomlinson sees it, Boyington “heisted” the identity of his squadron. “Those of us who were in the squadron at the beginning saw more fighting and shot down more Japanese airplanes than the squadron did later when its identity was swapped and it became Boyington’s outfit.” Long before Boyington came along, the commander of the VMF-214 “Swashbucklers” was Major George Britt.

Said Tomlinson: “After the Japanese no longer had any hope of taking back Guadalcanal, on April 7, 1943, they launched the biggest raid they ever sent against the island—67 Val dive-bombers escorted by 110 Zeros. We intercepted them with portions of three Army and four Marine squadrons flying Wildcats, F4U Corsairs, P-38 Lightnings, P-39 Airacobras, and P-40 Warhawks. Our ‘Swashbucklers’ squadron was credited with shooting down four Vals and six Zeros over Cape Esperance.

“I found myself going after one of those Val dive-bombers,” Tomlinson continued. “The six .50-caliber guns in the F4F-4 Wildcat were lubricated with cosmoline, which thickened in the extreme cold at high altitude and could prevent the guns from working. When I locked onto the last Val in the Japanese formation, five of my six guns froze and refused to fire. I gave it some throttle and got up right behind him, which gave me a close-up look at the two men in the Val. I could see the disturbed reaction of the gunner in the rear cockpit of the Val. He was shooting at me when my bullets hit him and chewed him up. This was not pretty at all. I knocked off pieces of the Val and got it smoking, then banked near Lunga Point just in time to get away from a brace of Zeros.”

That battle over Guadalcanal was one of the last in the Pacific for the Wildcat. Thereafter, only two squadrons in the Ellice Islands continued to fly the F4F. In June 1943, Tomlinson’s squadron converted to the F4U Corsair.

William P. Boland’s squadron did not. “Ours was the last squadron to fly the Wildcat fighter in combat,” said Boland. “We were still flying Wildcats when other Marines were defeating the Japanese in air battles while flying Corsairs and Hellcats.

“My squadron was VMF-441. It was one of the very few Marine squadrons to actually be commissioned in the combat zone, organized on October 1, 1942, at Tafuna airdrome, Tutuila Island, American Samoa, with Major Daniel W. Torrey as our first commander. Torrey was due for assignment elsewhere, so, on December 4, Captain Walter J. Meyer became our commander. Torrey, Meyer, and most of the Marines in Samoa had been fighting on Guadalcanal, and to them Samoa was a pleasant backwater after months of harsh fighting—a place of respite and refuge. The war was a lot less active there.”

Boland said that by this late juncture in the war Marines knew a lot about how to use the Wildcat effectively against the Zero. “The cockpit was spacious and comfortable,” he recalled. “You just had to get used to the plane’s annoying features, like the hand crank to put down the landing gear, but every airplane had its idiosyncrasies.

“From Samoa, we flew missions against bypassed Japanese outposts like Wotje and Maloelap. Later in the war, of course, VMF-441 flew a lot of combat in Corsairs—the squadron produced seven aces—but the Wildcat period was mostly unremarkable. At least, it was unremarkable until they decided to send a bunch of us to Funafuti. That island was only beginning to have an American presence but it would eventually become a staging base for the invasion of Tarawa.”

First Lieutenant (later Maj. Gen.) Ralph H. “Smoke” Spanjer was one of Boland’s fellow Wildcat pilots at Funafuti. “I was part of a four-plane advanced echelon to fly north from Samoa to the Ellice Islands,” said Spanjer, recalling Squadron 441’s initial move to Funafuti. “With external tanks we flew 700 miles with only one stop at the French island of Wallis and arrived over Funafuti. A PBY Catalina escorted us during the flight.

“To our dismay, the Navy Seabees’ desire for our protection exceeded their constructive efforts and we were forced to land on barely 1,500 feet of unprepared coral surface. The next day, we were alerted for our first business and did, in fact, chase a Japanese ‘Emily’ flying boat but lost it in some rather severe weather.”

On March 27, 1943, the SCR 270 ground radar operated on Funafuti by the Army’s 5th Defense Battalion detected the approach of unknown aircraft. Boland and Spanjer were launched against a possible radar target. They were soon in hot pursuit of four, twin-engine Mitsubishi G4M Type 1 “Betty” bombers.

“This was the latest in high-speed Japanese bombers,” Spanjer said. “Our tired F4Fs were straining to get in position for an attack. On the first pass, Captain Boland shot down the lead bomber, which exploded under fire of his six .50-calibers. Contrary to the official squadron history, my guns did not jam immediately. I maneuvered behind the number four ‘Betty,’ got off several bursts, and was able to inflict some damage before my guns froze. Captain Boland and I made one additional flat pass but the bombers outdistanced us.”

Boland, Spanjer, and other Marine Wildcat pilots spent the next four months hunting in vain for Japanese warplanes during daylight hours. During the dark, they caught accurate strings of Japanese bombs on the installations on Funafuti. The night bombing raids inflicted severe damage to an Army Air Corps squadron operating Consolidated B-24 Liberators from the island. It soon became apparent to the Marines that their problems were being caused by a lone Japanese “Nell” bomber that scouted out the island daily from high altitude. Even after regular night bombing attacks by the Japanese became few and far between, the lone “Nell” kept flying reconnaissance missions high over their heads, as if the Japanese were thumbing their noses at the Marines. According to Spanjer, Boland began to regard that Nell in very personal terms.

“No one wanted to get that Nell more than Boland,” said Spanjer. “He began what some later interpreted as a one-man campaign to defeat that solitary Japanese bomber.”

Another member of Squadron 441, Captain Norman Mitchell, had similar recollections. “The Japanese were scouting down through Nanomea and sometimes as far as Nukufetau,” said Mitchell, referring to other islands near Funafuti in the Ellice chain. “We saw that Nell bomber almost daily. William P. Boland got aboard a PT boat and had the PT boat drop him off with a New Zealand coast watcher on the island of Nanomea, where he observed the Nell’s operation for about a week. During that time, we sent up a section of two F4F Wildcats from Funafuti every day to attempt an intercept over Nanomea. Boland tried from his position on the ground to vector the Wildcats up to attack the Nell. The Wildcats carried extra fuel tanks under the wings to give them loiter time and ‘reach’ to catch the bomber. The Nell eluded us every time

“We just couldn’t get him,” Mitchell said. “Our communication seemed to be working. Our radar seemed to be working. We seemed to know where the Nell was, and Boland was giving us excellent guidance over the radio. But somehow, that Japanese heckler managed to escape from us every time. Every one of us wanted to get the Nell and we began to think it was not going to happen.”

The Marines learned after the war that the Nell was from a Japanese unit called the 755 Kokutai, operating out of Tarawa. While the war was going on, they did not know the Japanese names of their units or airplanes.

Spanjer shared Boland’s frustration. “For weeks, our Wildcats had been trying to catch up with that Nell,” said Spanjer. “Some of the missions were flown from Funafuti to Nui— where the Nell spent a lot of time. That was a round-trip of 280 miles, which meant that even with wing tanks the Wildcats wouldn’t have time to spend more that a few minutes attempting the kill. We tried for weeks to meet the enemy plane, sometimes missing only by minutes. On July 17, 1943, we believed we came within a minute or two of nailing the Nell.”

On August 8, 1944, Boland took off in a two-plane section with 1st Lt. Samuel G. Middleman on his wing. Soon afterward, the Army radar people told them there was an apparent Japanese aircraft over Nui, another island in the Ellice group. That meant a marathon flight of 140 miles each way, from Funafuti to Nui.

“It was a good thing the F4F Wildcat was so comfortable,” Boland said.

On that mission, everything broke right. “Once again, our communications worked. Once again, our ground-radar worked,” said Boland. “This time, we really knew where the Nell was. We had wanted to get that Nell for a long time. We managed to come up behind the Japanese bomber. I made a firing pass from the left rear quadrant and sent some .50-caliber into him. The Nell started to disintegrate and sent back pieces of debris that narrowly missed me. The pilot somehow had enough control to get the bomber down to very low altitude before he lost it. The Nell went down in Nui atoll, in water so shallow it didn’t sink. People told me the wreckage of that Nell was still readily visible in Nui lagoon 30 years later in 1974.”

Boland later commanded fighter squadrons VMF-215 from November 1944 to February 1945 and VMF-321 from March to August 1945. “I flew other fighters,” he said, “but the Wildcat enabled me to bag that bomber after weeks of trying.”

The American industrial heartland turned out 7,825 Wildcats during World War II, including 1,988 F4F models built by Grumman and 5,837 FM versions from General Motors. Foster Hailey, correspondent for the New York Times, summed up the Wildcat’s impact on history in 1943: “The Grumman Wildcat, it is no exaggeration to say, did more than any single instrument of war to save the day for the United States in the Pacific.”

Marine pilots agreed.

Robert F. Dorr is a U.S. Air Force veteran, retired diplomat, and author of the book Air Force One, a look at presidential aircraft and air travel. Fred L. Borch is a retired U.S. Army officer and currently serves as historian of the Judge Advocate School in Charlottesville, Virginia. He is the author of the book Kimmel, Short and Pearl Harbor.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments