By Peter Suciu

It has long been said that there is a right way to do things, a wrong way to do things—and the military way to do things. With the United States military, that way has included putting it all down on paper. Military manuals, while not exactly page-turners, have become much sought after by collectors, sometimes because these handy books are the only available sources of information on equipment that as been phased out of the American arsenal.

From the days of the American Revolution, U.S. armed forces looked to various European nations for inspiration on how to prepare for and conduct war. Various foreign advisers and observers assisted the newly founded nation in its early years, usually through oral teachings. Little was written down, and for much of the 18th and 19th centuries there were few formal guides or manuals for even the simplest military tasks.

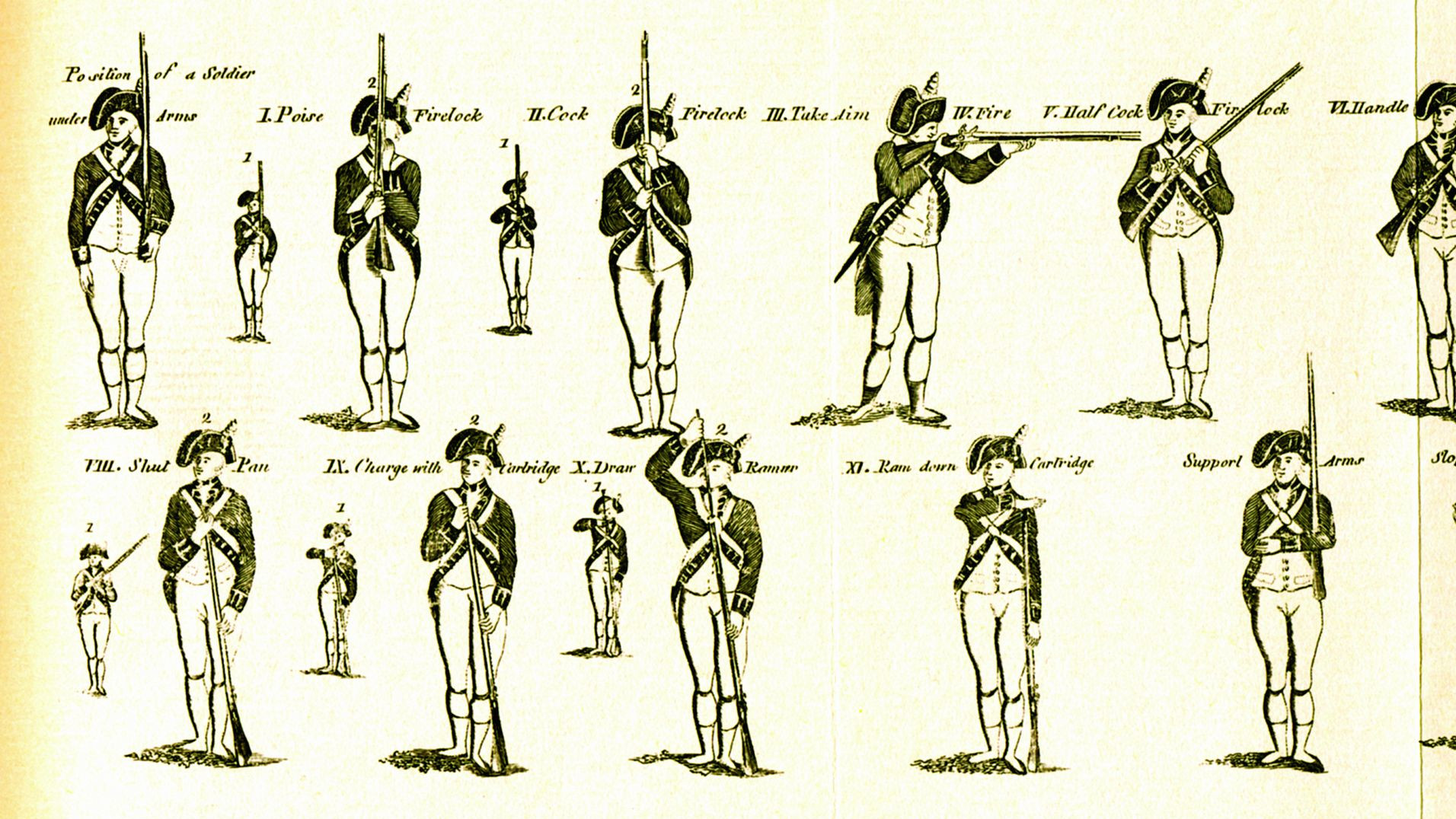

A major example of the foreign influence on American military practice was the manual of arms written and used by Baron Friedrich von Steuben to train Continental soldiers in General George Washington’s army during the terrible winter at Valley Forge. Steuben, who had served in the Prussian Army during the Seven Years’ War, volunteered his services to Washington and joined the army at Valley Forge in February 1778. Once there, he assembled a model company of 120 men to learn his European precepts of drilling and pass them along to other American soldiers. With the help of his French-speaking aide, Captain Benjamin Walker, Steuben instilled much-needed discipline and professionalism within the ranks. The next year he codified his training methods in Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States, commonly known as the “Blue Book.”

Steuben’s work remained the official drill manual for the U.S. Army through the War of 1812, when General Winfield Scott headed a board to draft a new manual based on the tactics used by Napoleon Bonaparte’s Grande Armée. The French-influenced manual was used through the Mexican War before being supplanted by Major William Hardee’s Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics in 1855 as the standard U.S. drill manual. Hardee’s revised 1861 manual was also used as the standard manual for the Confederate Army in the Civil War.

Following the Civil War, former Union Army general Emory Upton prepared a new book on infantry tactics, artillery, and cavalry drill. Upton revised his manual in 1873, and it was updated again following his death in 1881. The 1891 Infantry Drill Regulations remained in standard use through the Spanish-American War.

With the exception of the drill manuals, there were no actual domestic military field manuals available to the troops and their commanders, and those that were used were either imported from abroad or privately published by a few forward-thinking old soldiers. As a result, these early manuals are extremely rare today and are highly prized by collectors.

The first formal American field manuals were written in the 1880s. These were usually known as War Department Documents or Ordnance Department Documents. They were numbered consecutively and featured a branch numbering system as well. The early War Department Documents were akin to modern field manuals and were usually hardcover books, while Ordnance Department Documents were more like modern technical manuals and could be either hardcover or softcover.

One aspect of the manuals has remained consistent, regardless of whether it is an old pre-World War I document or a modern field manual. These are hardly the sorts of book one would read for casual relaxation. The information contained in them is often precise and useful, but these are not tomes that anyone would want to read from cover to cover in a single sitting.

There is some confusion about the differences between the types of manuals. Typical field manuals provided guidelines on how to perform a task, but were not intended as a step-by-step task guide. Technical manuals, on the other hand, were meant to be specific instructions that should be followed as closely to the letter as possible. The problem was that the instructions often were written by people who did not always understand what actual situations could be like in the field.

Following World War I, American manuals underwent a change. The most notable was that many manuals appeared in a format that would be familiar today, designed to be placed in binders and broken down into categories including those designated TR (Training Regulations), TM (Training Manuals), and TC (Training Circulars). As would be expected, the TR types were among the most common. The numbering system contained a prefix that would make sense to military professionals, and included multiple digits separated by a dash, such as TR 425-30. The first set of numbers was meant to denote the subject, while the second set of numbers denoted the number of books on the subject. Thus, the 425 category must contain at least 30 titles. This could make for a complex and confusing system.

By the late 1930s, the manuals system was updated, and the Training Regulations were merged into a series of branch Field Manuals. The results included a Basic Field Manual, Cavalry Field Manual, and other appropriate subjects. However, in the 1930s the manuals still did not use a numbering system, and were instead titled by subject. Because most of these manuals were destroyed when new ones were produced, they have become extremely hard to find.

During World War II, the manuals underwent the biggest change, and anyone who has served in the military since that time will be familiar with the filing system, which remains in place today. The primary types of manuals were reduced to the main categories of FM (Field Manuals) and TM (Technical Manuals), but to complicate matters there were additional categories, including TC (Training Circulars), ST (Special Texts), and FC (Field Circulars), among others.

The numbering system of Field Manuals included a one- or two-digit number followed by a dash, which was then followed by a one- or two-digit number. Thus, FM 9-50 was the number of the Department of the Army Field Manual for Bandaging and Splinting. The first number was for the subject classification, while the second number referred to the particular manual.

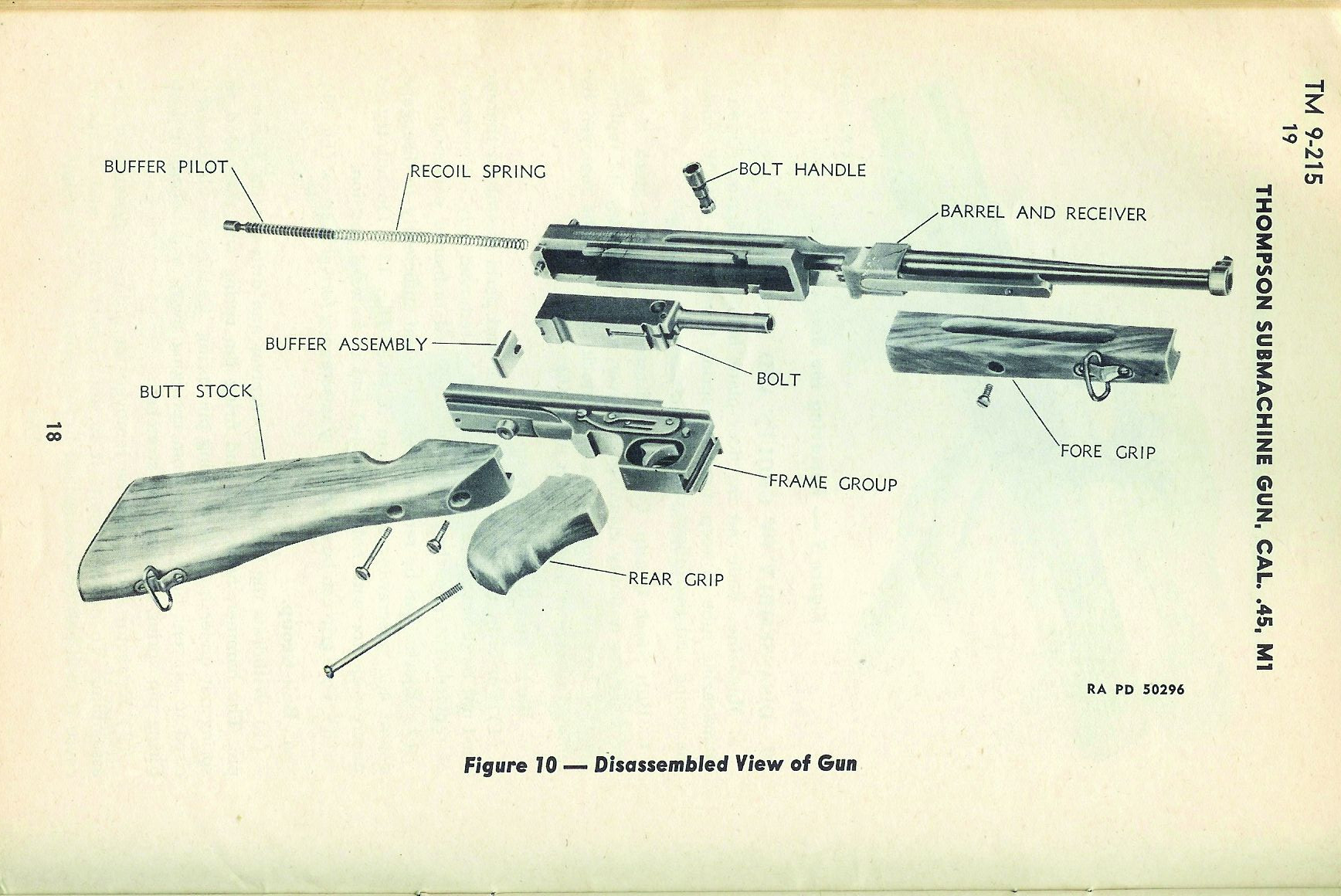

Originally, the Technical Manuals were numbered with a similar system, so that a TM 9-215 was the designation for the Thompson submachine gun, .45-caliber M1. In this case, the first number stood for the subject or branch of the Army. The “9” refers to an Ordnance Branch, and the second number refers to the particular manual.

The system became further complicated in the 1960s, especially in the case of ordnance equipment, when numbers began to resemble federal tax code numbers. There, one could find numbers such as TM 9-1005-211-34. The first set was for the branch, the second was the subject type, the third number represented the piece of equipment, and the fourth and final set of numbers referred to the level of maintenance the subject might require.

Among the most sought after manuals today are those that at one time may have been classified. The reasons for the level of secrecy, of course, depended on what was within the manuals. Most World War II-era ordnance manuals, for example, are listed as being for “Ordnance Personnel Only.” The 1946 edition of the U.S. Navy’s Bluejackets Manual, for example, breaks down the level of restrictions from the era: “Any information or material which must be circulated among naval and military personnel, but which must also be safeguarded against leakage to the enemy, is classified and marked in one of three ways. The classification of documents determines how many people will see them.

There were multiple levels of restrictions, according to the Bluejackets Manual. These included specific definitions:

“Secret. Secret matter is the most closely guarded and is considered to be of such importance that disclosure might endanger the national security. One subdivision of secret is top secret. Documents so classified are seen by very few people indeed. Any knowledge of secret matter which comes to a man outside of his assigned duties should be reported immediately to his superiors so that the leak may be found and plugged.

“Confidential. Confidential matter is second in importance and is of such a nature that disclosure would be harmful to the interests or prestige of the nation. Confidential material is never left unguarded. Any breaks in the security of confidential matter should be reported immediately.

“Restricted. This is the lowest classification. Restricted matter is limited in circulation to government or military personnel who are properly concerned with the information. Often matter which would normally be classified as confidential is classified restricted because the wider circulation is of more benefit than the additional security.”

After the war, most of the restricted manuals were declassified entirely, while most confidential material was downgraded to restricted. One decade after the end of the war, the remaining restricted material was also declassified. Declassification of secret material was handled on a case-by-case basis, however, with many items still classified more than 60 years later.

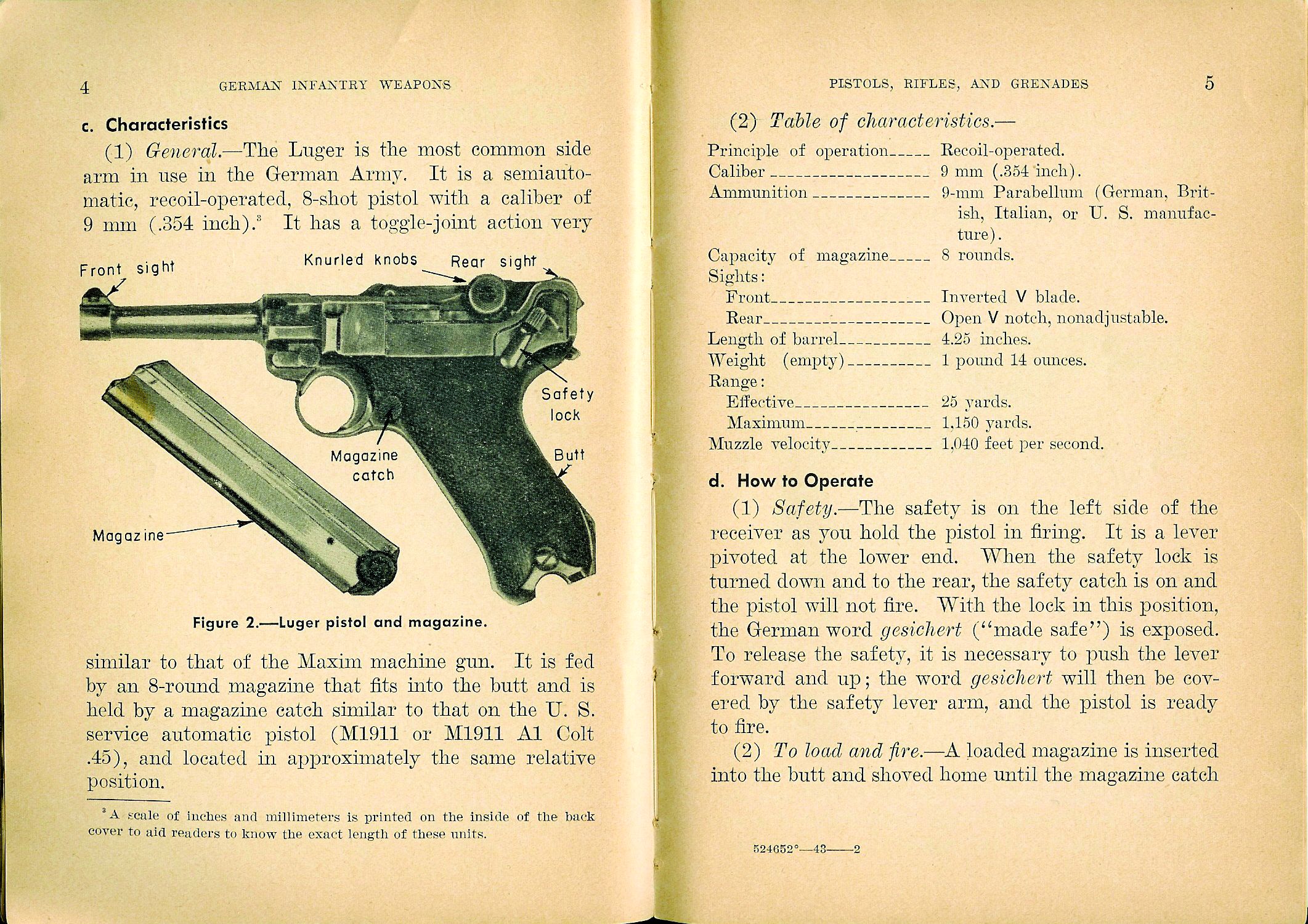

While the numbering system is enough to make one’s head spin, the most important thing to remember is that manuals used in World War II essentially fell into three broad categories. Shelley Shelstad, collector of declassified WWII recognition documents and owner of History-on-CDROM.com, explains: “There are those that cover recognition/capabilities of allied and enemy ships, aircraft, tanks, and equipment; those that cover training in use and repair of allied ships, aircraft, tanks, and equipment; and those that cover operations, both historical data on past operations and estimates of future operational capabilities.”

While many manuals are easy enough to find at local militaria shows, flea markets, and on the Internet, many are a bit harder to find. For those that aren’t available in print, Shelstad has produced digital reproductions. Shelstad adds that both the War Department, which included Military Intelligence, and the Navy Department, with its Office of Naval Intelligence, produced separate manuals covering the same ships and aircraft. “As might be expected, Military Intelligence tended to put its emphasis on tanks and land-based aircraft,” says Shelstad, “while Naval Intelligence tended to put its emphasis on ships and sea-based aircraft. In the last half of the war, they started producing joint recognition manuals that could be used by both the Army and the Navy. In general, these joint manuals were broader in scope, but skinnier on details than the single-service manuals.”

Today, most the manuals are still an affordable collectible, but a few from the late 1930s and early 1940s before the United States entered the war have become much harder to find, even for longtime document collectors such as Shelstad. The Holy Grail for collectors is those manuals in the ONI 41-42 Series, issued in December1944 covering the Japanese Navy. Although an index was released, one theory maintains that with much of the Imperial Japanese Navy safely at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean, it was decided that a follow-up series never needed to be published.

Again, it should be stressed that even the period manuals deemed “secret” probably are not going to be potboilers. For general reference regarding appearance and capabilities, modern sourcebooks probably have better, more accurate information, and they include information about equipment manufacturers and exact production dates.

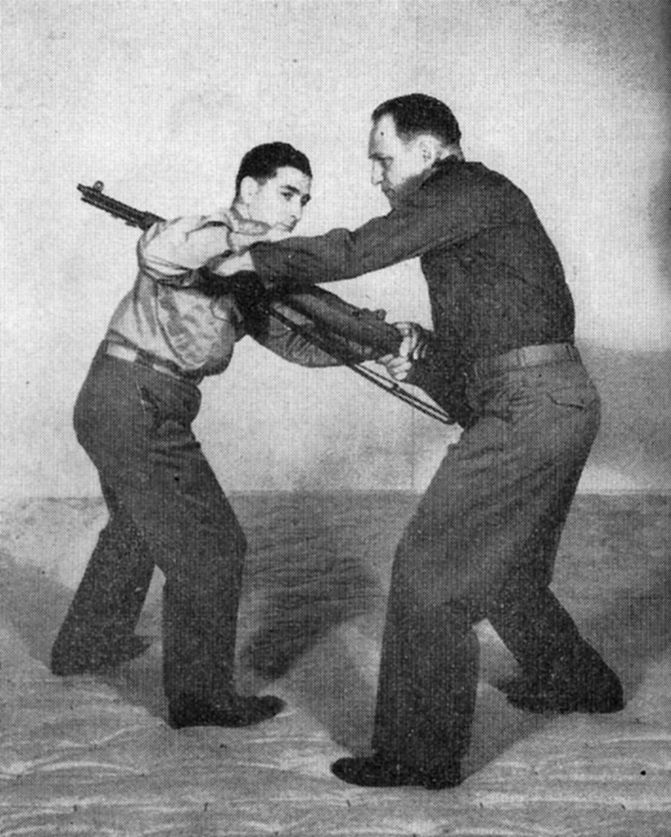

Although document collectors may be interested in the information, those interested in the related subject are more likely to seek out the corresponding manuals. This is why the various firearms manuals, including those in the American arsenal as well as the restricted manuals that were prepared on enemy weapons, have become the most sought after. There are numerous books on the M1 carbine. Manual TM 9-1276—Technical Manual and Ordnance Maintenance for Carbines Cal. 30, M1 and M1A1— provides the reader with a very detailed guide to stripping the weapon and even ways to do field repairs. Where the confusion arises is that this manual was published and updated numerous times, sometimes correcting information that was either not practical or was just wrong.

With improvements to equipment over time, the actual item and the manual might not be entirely in sync. On the topic of operations or tactics, things have changed many times as well. Some manuals, such as FM 21-75, have five editions covering 45 years of changes in doctrine. “The validity of these WWII manuals is largely dependent on the intended use,” emphasizes Shelstad, adding that for some items the manual might not be all that helpful.

On the topics of larger equipment, most modern source books are limited to one or two line drawings and three or four photos. There is a notable difference in the older manuals especially for larger vehicles. This is especially true for noncapital warships such as cruisers and destroyers. The WWII warship recognition manuals may include over 40 images showing how the ship would appear from different targeting angles and elevations.

Such detailed information can be important to those wanting to build models or for authors needing to confirm information on a subject, but for the casual reader it may prove less than interesting to read. Shelstad stresses that the WWII manuals on ships and aircraft typically include combat information such as firing arcs of weapons, something that seldom appears in modern source books. Conversely, WWII manuals almost never include information on the manufacture of the equipment and tend to merely approximate information that was not needed for the intended mission. This can be useful, but as Shelstad notes: “If you want to know who built a specific ship, how long it was to the nearest half-inch, and what kind of power-plant it had, the modern source book is the place to go. If you want to know if a Japanese ‘Betty’ bomber could defend itself from an attack from below and directly behind, see a WWII manual with targeting information.”

Many of the manuals remain of interest, especially those from World War II and immediately beforehand, because they often are the only sources of information written at the time. While some of the information may seem dated and even contain an error or two, particularly when enemy combatants’ equipment is mentioned, the manuals remain a virtual window on the past. Because much of the equipment has been lost over the years, having such information still available is a good reminder. And for those who own particular weapons, vehicles, or gear, nothing beats having a specific manual from the past at one’s fingertips

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments