By Al Hemingway

In 1958, Royal Marine General Sir Leslie Hollis visited the old Central War Room in London where he had spent numerous hours during World War II. Situated 50 feet beneath Whitehall, the sprawling six-acre command post consisted of a maze of rooms and hallways where Britain’s ground, air, and sea commanders made momentous decisions regarding their nation’s strategy during the life-and-death struggle.

As he scanned the room where the country’s leaders convened, Hollis’s eyes fixed on the chair where the wartime prime minister, Winston Spencer Churchill, would sit and hold court. Blank papers were scattered about and there sat the bucket where Churchill would toss his habitually half-smoked cigars. Here the prime minister would cajole, yell, and prod his military commanders to achieve victory over German dictator Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime. If this could not be accomplished, Churchill knew better—and sooner—than anyone, it would mean the end of the island nation.

As he scanned the room where the country’s leaders convened, Hollis’s eyes fixed on the chair where the wartime prime minister, Winston Spencer Churchill, would sit and hold court. Blank papers were scattered about and there sat the bucket where Churchill would toss his habitually half-smoked cigars. Here the prime minister would cajole, yell, and prod his military commanders to achieve victory over German dictator Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime. If this could not be accomplished, Churchill knew better—and sooner—than anyone, it would mean the end of the island nation.

Although there has been a plethora of biographies about Churchill, in his new offering, Warlord: A Life of Winston Churchill at War, 1874-1945 (HarperCollins, New York, 2008, 864 pp., photos, maps, index, notes, $39.95, hardcover), retired U.S. Army Lt. Col. Carlo D’Este focuses on Churchill’s military background and how it shaped his thinking—for both good and ill—during England’s greatest wartime challenge.

Born amid great family wealth in 1874, Churchill was a rambunctious and often undisciplined child. He had a deep love for his mother and father, despite their cold and distant relationship to each other and their eldest child. He spent countless hours playing with his toy soldiers and envisioning himself leading a great army one day.

Although brilliant intellectually, Churchill’s poor grades kept him out of Oxford or Cambridge. Instead, he graduated from Sandhurst, England’s royal military academy, in 1894. He saw service in the cavalry in India, Egypt, and the Sudan, where he participated in the last cavalry charge in British history in 1898 at Omdurman. He also served a brief stint as a newspaper correspondent during the Boer War and was briefly held as a prisoner of war before escaping amid great hoopla and international publicity. During World War I, he served as First Lord of the Admiralty and helped plan the disastrous campaign at Gallipoli, for which he took more than his fair share of responsibility and blame. At his insistence, he commanded a battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers on the Western Front

During the years preceding World War II, Churchill was in political hibernation. The dark cloud of Gallipoli hung over him, squashing any chance for a successful political career. He often went into deep depression, which he referred to as his “black dog.” He spent many hours painting in an attempt to overcome his deepening malaise.

Despite being a self-inflicted recluse, he remained outspoken when war clouds loomed in Europe. He constantly criticized the government’s appeasement policy toward the fascist regimes of Hitler in Germany and Benito Mussolini in Italy.

When war was declared in September 1939, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, who had attempted to placate the Nazis, came under attack in both houses of Parliament. Churchill seized his opportunity and was selected as prime minister on May 10, 1940, when Chamberlain resigned. Although condescending, cantankerous, and moody, Churchill’s sheer audacity and inspiring words uplifted the spirits of the British people. His speeches instilled a sense of renewed pride and a willingness to fight to the death to defend the home island.

His extensive military training, Churchill believed, made him an expert on strategy—much to the chagrin of his commanders. His constant meddling was a source of irritation and, at times, proved detrimental to the war effort. He relieved generals and admirals at will, some of whom were exceptional field commanders, while ignoring others, including Sir William Slim, whose outstanding performance in the Far East went largely unnoticed. Churchill concentrated on winning the war in Europe, but argued vehemently with American generals Dwight D. Eisenhower and George C. Marshall about how it should be done. Churchill was a proponent of the Mediterranean approach, through Sicily and Italy, which he called “the soft underbelly,” to draw German troops away from France. The Americans, by contrast, were strong advocates of the cross-Channel invasion. He was lukewarm to the idea, visualizing the sort of trench-style warfare that remained indelibly etched in his mind after his service on the Western Front in 1916.

In spite of all his shortcomings, the charismatic Churchill was the linchpin for the war effort during the turbulent years of 1940-1945 in Great Britain. A lesser man would have buckled under the extreme hardships of the job. Not Churchill—he thrived on it. The strain of leadership eventually took its toll, as he suffered several heart attacks, pneumonia, and fatigue, as the conflict slowly grinded on. Still, he was seemingly everywhere, mingling with the populace, facing down German bombers during the Blitz, chomping on his ever-present cigar and flashing his famous V-for-victory sign.

“While opinions and assessments of Churchill will continue endlessly, one conclusion is beyond dispute,” writes D’ Este. “It is this: His romantic view of war and his inability to understand various aspects of its prosecution notwithstanding, Churchill nevertheless was the only man in Britain who could have led his nation from the dark hours of defeat with unwavering vision and bulldog tenacity.” It is an achievement that cannot be overvalued, by Great Britain or the rest of the free world.

The Last Lincoln Conspirator: John Surratt’s Flight from the Gallows by Andrew C.A. Jampoler, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2008, 312 pp., photos, maps, index, notes, $29.95, hardcover.

The Last Lincoln Conspirator: John Surratt’s Flight from the Gallows by Andrew C.A. Jampoler, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2008, 312 pp., photos, maps, index, notes, $29.95, hardcover.

On Good Friday, April 14, 1865, while watching the play Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C., President Abraham Lincoln was shot and killed by noted stage actor John Wilkes Booth. After a night-long struggle, the president died early the next morning at the Peterson House, a boardinghouse located across the street from the theater. Lincoln’s death sent shock waves throughout the nation and the world.

A huge manhunt quickly snared the individuals believed to be involved in the conspiracy to murder Lincoln. Booth, the ringleader, was cornered some days later in a tobacco barn in Maryland and killed by Sergeant Boston Corbett, who fired without orders through a slat in the barn’s wall. Within weeks, four of the alleged perpetrators were hanged and several others were sent to the American version of Devil’s Island, the Dry Tortugas in the Florida Keys.

However, one man managed to elude the dragnet—John Harrison Surratt, son of Mary Surratt, one of the four accused conspirators (and the only woman) hanged for the crime. Surratt’s flight from capture, from upstate New York, to Canada, England, Italy, and eventually Egypt, where he was finally captured, is the stuff of dime store novels.

Surratt was slapped into irons and transported back to Washington to stand trial for conspiracy in the killing of the president. Eyewitnesses claimed that they saw him with Booth on the day of the shooting. But was it Surratt? Or was it Ed Spangler, one of the alleged conspirators, who tended to Booth’s horse that fateful night? Surratt was a Confederate courier who frequently carried dispatches across Union lines. He was sent to Canada to deliver messages to General Edwin Lee of the Confederacy Secret Service during that time frame. He then said Lee had instructed him to go to Elmira, New York, to gather intelligence about the notorious Federal prison camp there. Lee was hoping he could free the prisoners and have them join the ranks of the Confederate Army.

Surratt’s lawyers argued that it was humanly impossible for him to have gone to Canada, then to New York, then to Washington to assassinate Lincoln, and then back to New York. After a lengthy trial that saw the senior defense attorney, Joseph Bradley, and Judge George Fisher, almost come to blows (Bradley would later be disbarred by Fisher at trial’s end), Surratt was acquitted.

Attempting to pick up the pieces of his life, Surratt was a failure at business. The Maryland native then tried his hand at the lecture circuit to tell his side of the Lincoln story. After a successful engagement in Rockville, Maryland, he took his show on the road to New York, where he received a cool reception from the audience and the press, who wrote that Surratt was “hawking his mother’s corpse.” He was forced to cancel his Washington engagement when an uproar ensued that threatened to turn into a street riot. He eventually was employed by the Baltimore Steam Packet Company, which he served faithfully for more than 40 years prior to his death in 1916.

Last Man Standing: The 1st Marine Regiment on Peleliu, September 15-21, 1944 by Dick Camp, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2008, 308 pp., photos, maps, notes, index, $28.00, hardcover.

Last Man Standing: The 1st Marine Regiment on Peleliu, September 15-21, 1944 by Dick Camp, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2008, 308 pp., photos, maps, notes, index, $28.00, hardcover.

On September 15, 1944, leathernecks of the 1st Marine Division landed on Peleliu, an island in the Palau group that was shaped like a lobster’s claw. Ostensibly, Operation Stalemate, the official name of the campaign, was devised to remove a air-based Japanese threat from General Douglas MacArthur’s right flank and secure a base to support his operation into the southern Philippines. But with the once-mighty Japanese air force notably absent from the area, many felt that the campaign should be scrapped. Admiral Chester A. Nimitz, commander in the central Pacific, overruled them and the operation went on as planned.

The battle-hardened Marines of the 1st Division were given the unenviable assignment of securing the island, seven miles of unforgiving coral and mountains where the Japanese had ample time to build formidable defense works. By mid-October, the Marines had taken most of the island, but at a terrible cost. The 1st Regiment, under Colonel Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller, had the worst job of all. It was assigned to drive the enemy from the Umurbrogol Mountain range. Their combat report later stated: “Along its center, its rocky spine was heaved up in a contorted mass of decayed coral, strewn with rubble, crags, ridges and gulches thrown in a confusing maze.”

Infantrymen could not dig into the solid coral and were thus exposed to withering Japanese fire. When shells landed, bits of coral acted like shrapnel, inflicting additional wounds. The enemy had buried themselves like moles into the side of the ridge and fought to the death. When it was finally over, the Marines suffered more than 6,500 casualties, with Puller’s men taking the brunt of the suffering. Two of his battalions lost half of their compliment and a third an incredible 70 percent—the worst losses by a single unit in the history of the Marine Corps.

Camp’s book goes into great detail about the battle and the various personalities on both sides. It would leave a blemish on the career of Puller and destroy that of Maj. Gen. William H. Rupertus, the crusty division commander, who continually ordered his men into futile frontal assaults. As the author states succinctly: “Peleliu was a battle that should not have happened.”

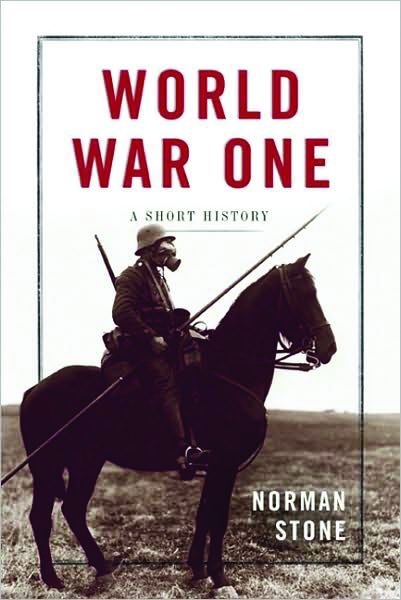

World War One: A Short History by Norman Stone, Basic Books, New York, 2009, 240 pp., photos, maps, index, notes, $25, hardcover.

World War One: A Short History by Norman Stone, Basic Books, New York, 2009, 240 pp., photos, maps, index, notes, $25, hardcover.

The striking image of a World War I German soldier atop a horse, wearing a gas mask and carrying a lance, is an excellent choice for the cover of this book. The photograph depicts the evolution of the war, from its romanticized beginnings in 1914 to the grueling four years of senseless bayonet charges and miserable trench warfare that left millions dead or wounded on the battlefield.

Europe had never seen warfare on such a scale until the outbreak of the conflict after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in June 1914. From Europe to the Middle East, countries took sides and slugged it out until they had almost depleted themselves. In 1917, the United States became actively involved after several years of neutrality, and the bloodshed was over in November 1918.

Stone, a professor at Oxford University, gives an insightful synopsis of the causes, fighting, and treaty that ended the hostilities. When the church bells rang on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month in 1918, the world was once again at peace. Within a few short years, however, political unrest would take hold in Germany and a new fanatical despot would rise to power, plunging the world into yet another global conflict, one that would overshadow the previous war in both numbers and sheer inhuman hellishness.

Three Days in the Shenandoah: Stonewall Jackson at Front Royal and Winchester by Gary Ecelbarger, University of Oklahoma press, Norman, OK, 2008, 273 pp., photos, maps, index, notes, $29.95, hardcover.

Three Days in the Shenandoah: Stonewall Jackson at Front Royal and Winchester by Gary Ecelbarger, University of Oklahoma press, Norman, OK, 2008, 273 pp., photos, maps, index, notes, $29.95, hardcover.

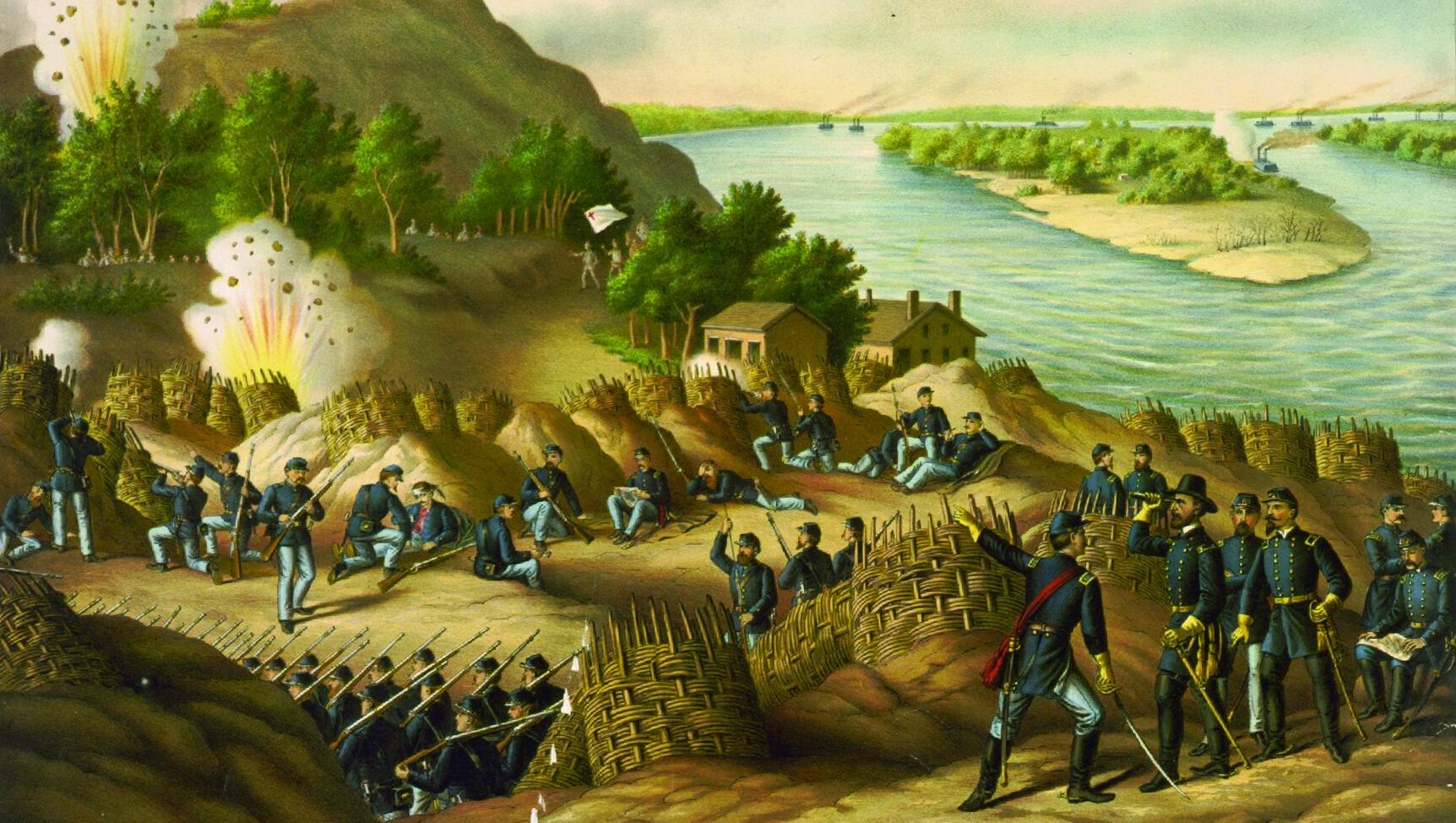

After their initial victory at First Manassas, the Confederacy’s prospects for a quick victory were dashed. In the western theater, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant seized Fort Donelson, Tennessee, in February 1862 and, after being surprised, regrouped and defeated the Rebel army at the bloody Battle of Shiloh two months later. In the east, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan was poised to strike at Richmond, the southern capital, where his massive army was fast approaching from the southeast in the ongoing Peninsula campaign.

Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy, desperately needed a miracle. He would soon get one in the person of the eccentric Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, commanding a polyglot force of 17,000 troops in the Shenandoah Valley.

Jackson’s lightning movements were bold and caught the Federals off guard. Although commanding a relatively small force, Jackson’s threatening actions worried President Abraham Lincoln so much that he dispatched additional men to quell the threat aimed directly at Washington, D.C. By doing so, Lincoln and his cabinet played right into Jackson’s hands, preventing reinforcements from being sent to McClellan’s army.

The author carefully points out Jackson’s weaknesses, noting that he would send his units into battle in a piecemeal fashion. His artillery was no match for the Federals and even his cavalry, normally superior to the North’s at this stage of the war, performed poorly. Despite this, Jackson overcame his setbacks and managed to elude and outmaneuver a 60,000-man army. He capitalized on Union Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks’s tactical errors and forced him to withdraw across the Potomac River. Jackson’s exploits earned him celebrity status in the South—only to be snuffed out one year later at Chancellorsville, where he was fatally wounded by friendly fire.

The Spartacus War by Barry Strauss, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2009, 288 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $26.00, hardcover.

The Spartacus War by Barry Strauss, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2009, 288 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $26.00, hardcover.

Not much is known about the early life of the Roman slave Spartacus. He was born in Thrace, in present-day Bulgaria, and served as a soldier in the Roman Army. For reasons still not clear, he and his wife were both sold into slavery. Spartacus was sent to gladiator school and escaped with 70 others, making his way to Naples with a large cache of weapons. There, he plotted revenge on his enslavers.

Because of his military training, Spartacus was a formidable foe. He began to train other slaves and soon had a force of 60,000 rebels that soundly defeated the Roman Army and for a time controlled southern Italy. While attempting to escape across the Strait of Messina to Sicily, Spartacus was betrayed by pirates and his ragtag band was surrounded and captured by eight Roman legions.

Even his death is shrouded in mystery. Some reports had Spartacus wounded in the thigh and fighting to the death. Another states that his friends ran and left him to fend on his own. According to the author, Spartacus was not crucified, as the famous 1960 movie suggests, but probably buried in an unmarked grave with countless others.

“Spartacus was a failure against Rome but a success as a mythmaker,” writes Strauss. “No doubt he would have preferred the opposite, but history has its way with us all. Who, today, remembers Crassus? Pompey? Even Cicero is not so well remembered. Everyone has heard of Spartacus.”

Maverick Military Leaders: The Extraordinary Battles of Washington, Nelson, Patton, Rommel, and Others by Robert Harvey, Skyhorse Publishing, New York, 2009, 442 pp., photos, index, $27.95, hardcover.

Maverick Military Leaders: The Extraordinary Battles of Washington, Nelson, Patton, Rommel, and Others by Robert Harvey, Skyhorse Publishing, New York, 2009, 442 pp., photos, index, $27.95, hardcover.

Writer Robert Harvey has assembled stories about a collection of military leaders whose fearlessness and maverick style of command set them apart from other generals—everyone from Englishman Robert Clive, whose exploits in India became legendary in spite of his often cruel nature, to American general Douglas MacArthur who, although a great tactician in World War II, failed miserably in the Korean conflict when he did not heed his own intelligence reports.

One of the most intriguing characters in the book is James Wolfe, the British officer who seized Quebec in 1759 and ended French rule in North America. By the age of 21, Wolfe had already participated in numerous military campaigns, from the Battle of Dettingen in 1743 to Falkirk and Culloden in 1746 and Lauffeld in 1748. He was promoted to colonel before his 30th birthday. Wolfe was given the rank of major general by William Pitt the Elder and ordered to head the attack on Quebec City. After a previous defeat, he changed his strategy and led 200 warships and 9,000 troops up the St. Lawrence River to perform an audacious amphibious landing. His men scaled the precipitous cliffs and, in a brief but bloody battle, defeated French on the Plains of Abraham.

No mere hagiography, Harvey’s book goes into detail on each leader’s flaws, as well as their astute leadership qualities. Each individual, despite his idiosyncrasies, was undoubtedly brave and, more importantly, knew how to bounce back from defeat—whether on the battlefield or in their personal lives.

Crusader Castles in the Holy Land: An Illustrated History of the Crusader Fortifications of the Middle East and Mediterranean by David Nicolle, Osprey Publishing, New York, 2008, 240 pp., photos, illustrations, maps, index, $25.95, hardcover.

Crusader Castles in the Holy Land: An Illustrated History of the Crusader Fortifications of the Middle East and Mediterranean by David Nicolle, Osprey Publishing, New York, 2008, 240 pp., photos, illustrations, maps, index, $25.95, hardcover.

Once again, Osprey Publishing has produced a book filled with magnificent photographs, meticulous artwork, and detailed maps that focus on the beautiful castles constructed by the Crusaders as they marched across the Holy Land in their ultimately foiled attempt to spread Christianity through the Middle East.

Myriad stone and masonry fortresses of various shapes and sizes dotted the landscape from Palestine to Syria. These symbols of Christianity were used as both defensive and offensive bases of operations. Beginning with the First Crusade in 1096, the author traces the fortifications up to the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century.

Nicole’s book could serve as a useful guide to anyone planning a trip to the region. The social, religious, and military aspects of the particular area are discussed in detail, along with the history of each castle. The author notes that many of them are now shattered ruins, although some of the lesser-known citadels can still be viewed. Because they were called by different names by the various people who resided in the region, a list is helpfully provided with the corresponding names in French, Latin, Arabic, Turkish, and Hebrew.

Soldiers Once: My Brother and the Lost Dreams of America’s Veterans by Catherine Whitney, Da Capo Press, New York, 2009, 224 pp., photos, $25.00, hardcover.

Soldiers Once: My Brother and the Lost Dreams of America’s Veterans by Catherine Whitney, Da Capo Press, New York, 2009, 224 pp., photos, $25.00, hardcover.

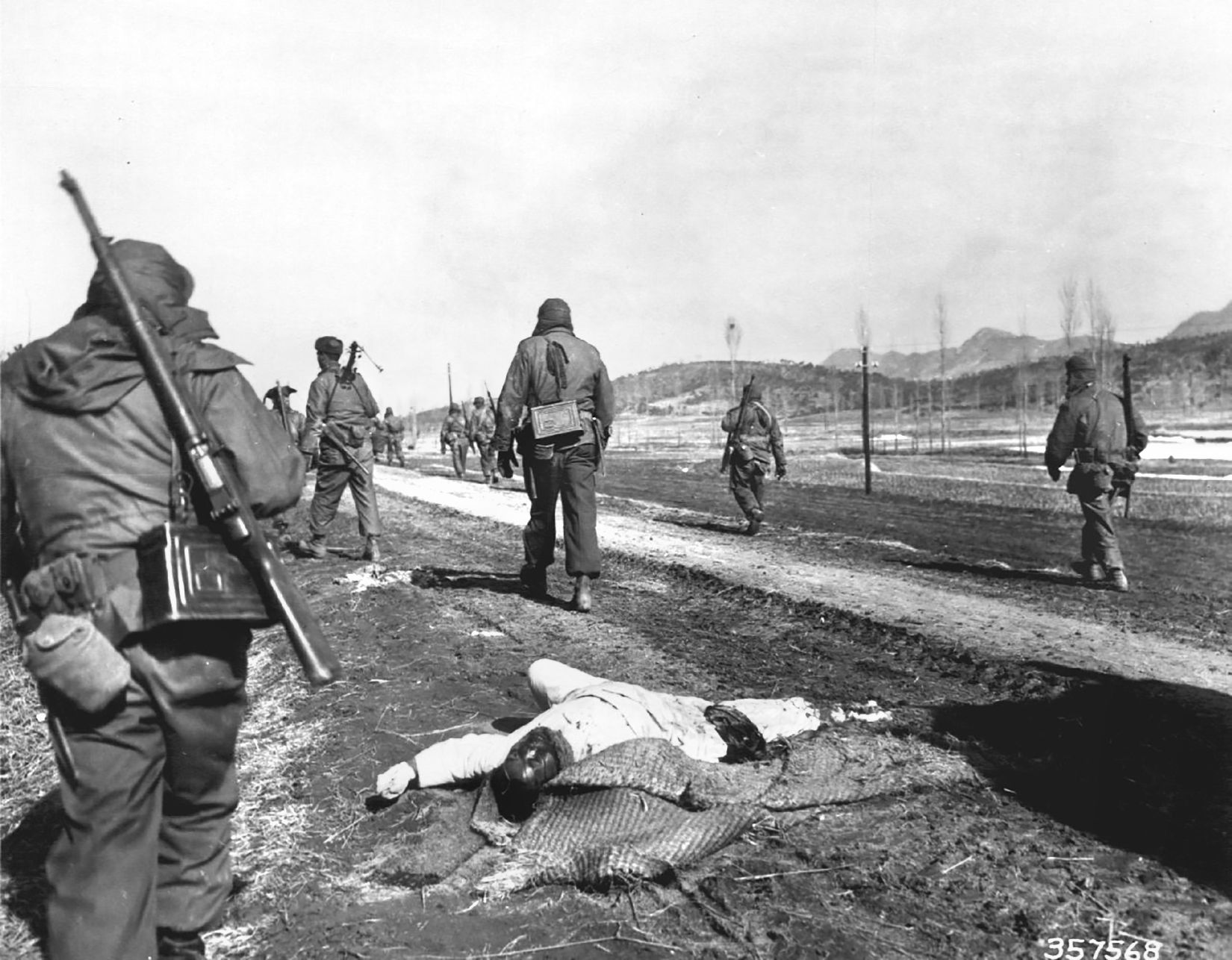

Military historians and history buffs enjoy dissecting battles, arguing strategy, and discussing tactics employed by leaders in mankind’s various conflicts. Although this is frequently enlightening, one should never forget that there is a human side of war, and that it is the humble foot soldier that usually bears the brunt of the fighting and dying.

Although at first discouraged by her family, Catherine Whitney finally convinced them that a book about their deceased brother, SSgt. James Whitney, USA (Ret.), was valuable, not only to enable them to have closure, but also to help other veterans suffering from the psychological effects of war.

Whitney served 20 years in the Army, including three tours of duty in Vietnam, where he earned the Purple Heart. He retired from the military, only to find himself isolated and unable to cope with the rigors of civilian life. He became an alcoholic and was prone to violent behavior on occasion. Alone and destitute, he died in 2001.

Although the book is a poignant memoir of her deceased brother, the author also had other motives in writing it. With the present war on terror being waged in Iraq and Afghanistan, she is worried that same fate might await American soldiers when they return to civilian life after witnessing the horrors of war.

“As I watched a fresh crop of soldiers go off to war, I wondered how we would prevent them from suffering Jim’s fate,” Whitney writes. “I saw a significant disconnect between what we say about supporting our troops and what we actually do to support them—not just when they’re at war, but when they return home.” It is an ongoing concern for all Americans.

The Illustrious Dead: The Terrifying Story of How Typhus Killed Napoleon’s Greatest Army by Stephan Talty, Crown Publishing, New York, 2009, 336 pp., illustrations, maps, $25.95, hardcover.

The Illustrious Dead: The Terrifying Story of How Typhus Killed Napoleon’s Greatest Army by Stephan Talty, Crown Publishing, New York, 2009, 336 pp., illustrations, maps, $25.95, hardcover.

When Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Russia in the spring of 1812, many believed his 600,000-man army was unstoppable. The “Little Corporal” now controlled most of Western Europe and was moving to subjugate the remainder of the Continent. By the end of the year, however, the magnificent Grande Armée had suffered a humiliating defeat. Stubborn Russian resistance, starvation, and harsh winter conditions eventually drove the decimated force back to France. Napoleon’s harrowing ordeal in Russia would seal his fate, and he would be exiled to the island of Elba shortly thereafter.

Journalist Stephan Talty offers another reason for the retreat and horrendous casualties of the campaign. Typhus (or rickettsia), he notes, left thousands of French soldiers buried in graves along the campaign route. In the town of Vilna, Lithuania, in 2001, workers uncovered mass graves that were first believed to be remains of victims tortured and killed by the Russian KGB. Upon closer examination by archeologists, they were revealed to be the skeletons of soldiers who had served with Napoleon. Using modern forensic science, the DNA of the dead confirmed that many had succumbed from the dreaded disease.

An epidemic had swept the countryside and managed to do what no general or army could accomplish—decimate Napoleon and his invaders. Talty estimates that 400,000 of Napoleon’s men died in the campaign, less then 25 percent as a result of combat. The remainder of the deaths was the result of starvation, cold, and disease, with typhus “the lead killer on the campaign.” As Talty states: “Rickettsia, not [Gen. Mikhail] Kutuzov and not ‘General Winter,’ had tripped the Great Army into its Russian grave.”

At War with the Wind: The Epic Struggle with Japan’s World War II Suicide Bombers by David Sears, Citadel Press, New York, 2008, 400 pp., photos, index, $24.95, hardcover.

At War with the Wind: The Epic Struggle with Japan’s World War II Suicide Bombers by David Sears, Citadel Press, New York, 2008, 400 pp., photos, index, $24.95, hardcover.

Ask any World War II U.S. Navy veteran who experienced a kamikaze attack, and he will tell you how horrifying it could be. The bulk of the suicide bombers appeared later in the war, especially during the battle for Okinawa, when most Japanese leaders realized that the Allies were inching ever closer to their homeland.

A U.S. Navy veteran of the Vietnam conflict, author David Sears has compiled a compelling account of the dreaded kamikazes. He interviewed hundreds of survivors and gleaned countless documents to tell their often heart-wrenching stories. He also included a section entitled “Roll Call.” Among the information listed there are the Purple Heart recipients, the names of their ships, how many battle stars they were awarded, unit citations, and those killed in action or lost at sea.

Many Americans cannot fathom a nation sending their young people to certain deaths in such a ghastly manner. The Japanese, however, were willing to attempt anything to halt the Allied juggernaut. Today, American forces are still encountering suicide bombers, albeit not as sophisticated as those piloting a dive-bombing airplane, but unfortunately just as deadly.

F6F Hellcat at War by Cory Graff, Quayside Publishing, Minneapolis, MN, 2009, 160 pp., photos, index, $24.99, softcover.

F6F Hellcat at War by Cory Graff, Quayside Publishing, Minneapolis, MN, 2009, 160 pp., photos, index, $24.99, softcover.

Although not the quickest or most maneuverable airplane in World War II, the Grumman F6F “Hellcat” was pilot’s dream. It could accelerate, move beautifully in a spin, and land on an aircraft carrier with ease. Company engineers even dropped one from a height of 10 feet to reproduce a free-fall drop. The plane did not suffer any damage. Then they repeated the same process, this time at 21 feet, and once again the Hellcat’s gear remained intact.

Graff has compiled numerous photographs, many of them in color, along with other data on the celebrated fighter. More than 5,000 enemy aircraft were shot down by the 12,275 Hellcats manufactured by war’s end. In contrast, the seemingly indestructible fighter suffered only 270 losses of its own—a kill ratio of 19-to-1. Approximately 93 American pilots became aces while flying the plane.

Ask any Hellcat pilot still around today about the airplane and he will likely attest to its durability and stellar combat performance. One carrier pilot even remarked: “If this plane could cook, I’d marry it!”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments