By Allyn R. Vannoy

While supply and logistics may seem like dull, dry topics, they are absolutely essential to military operations, for no victory can be achieved without a steady, uninterrupted flow of food, fuel, ammunition, clothing, medical supplies, and other key matériel.

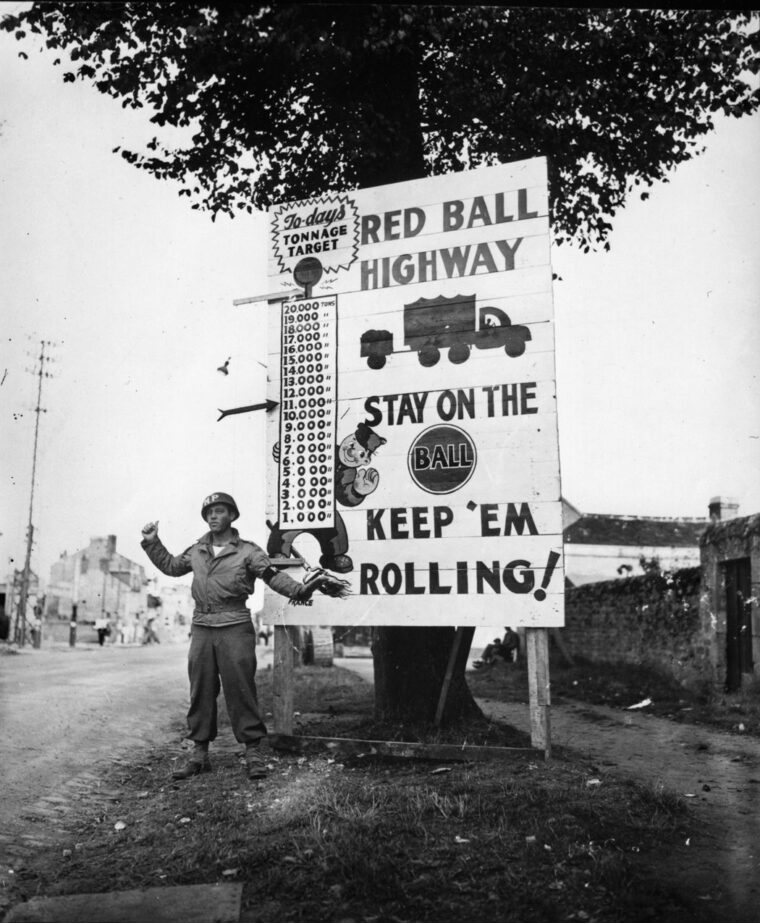

Never was this so clearly the case than when millions of men crossed from southern England to northern France in June 1944. To get the supplies to an army on the move became the role of the U.S. Army’s “Red Ball Express.” Far from being dull, the story of this vital operation was filled with action, adventure, and danger.

The Red Ball Express was the result of a sudden and unplanned situation that the U.S. Army recognized and responded to quickly as it advanced across northern France in the summer of 1944. The operation––born out of necessity––lasted only three months, from August 25 to November 16, 1944, and involved thousands of men and thousands of vehicles.

Adding to the logistics crisis that necessitated the operation were continually changing requirements and the activities of Paris gasoline gangs. The Express also presented an opportunity for African-Americans to prove themselves and contribute to the campaign in Europe.

Operation Overlord, the invasion of Normandy, followed months of intensive preparation. An absolutely critical part of the overall plan was making sure that the million-man-plus U.S. Army had all the essential supplies it would need once it reached the Continent.

To ensure this, the War Department early on established the Services of Supply, ETO, in England on May 24, 1942, to take charge of the growing mountains of supplies and to prepare to move these mountains across the English Channel. (After D-Day, the organization’s name was changed to Communications Zone, or COMZ; today it is known as the Army’s Quartermaster Corps.)

Commanding this massive organization was the egotistical, hard-driving, and ultra-religious Maj. Gen. John Clifford Hodges Lee. (Behind his back, some of those who dealt with him called him “Jesus Christ Himself,” based on his initials.)

Of Lee, Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower wrote in Crusade in Europe, “Because of his mannerisms and his stern insistence upon the outward forms of discipline, which he himself meticulously observed, he was considered a martinet by most of his acquaintances. He was determined, correct, and devoted to duty; he had long been known as an effective administrator and as a man of the highest character and religious fervor. I sometimes felt that he was a modern Cromwell, but I was ready to waive the rigidity of his mannerisms in favor of his constructive qualities. Indeed, I felt it possible that his unyielding methods might be vital to success in an activity where an iron hand is always mandatory.”

Ike also noted the indispensable nature of an efficient logistics system: “The work accomplished under [Lee’s] direction was so vital to success and so vast in proportion that its description would require a book in itself.”

Critical to ground operations was having a sufficient supply of POL (Petroleum-Oils-Lubricants). Allied logisticians in England worked out a detailed plan for POL support on the Continent. All vehicles used in the assault were to arrive on the beachhead with full fuel tanks and carrying extra gasoline in five-gallon jerrycans, otherwise known as “packaged distribution.” This was to continue throughout the invasion’s initial phase, D-Day to D+41. Planners had predicted a fairly slow-paced offensive, allowing for systematic construction of base, intermediate, and forward-area supply depots. In the meantime, it was hoped that the early capture and development of the Cherbourg port facilities on the northern tip of the Cotentin Peninsula, by around D+15, would enable combat engineers to begin laying three six-inch fuel pipelines toward Paris.

Pipelines were expected to eventually move about 90 percent of all POL entering the European Theater to forward area terminals or transfer points. By D+90, it was planned that the front line would be anchored on the banks of the Seine. The post-Overlord period, D+91 to D+360, would have the Army pushing steadily eastward to the Rhine, where it was assumed the war’s final showdown would occur.

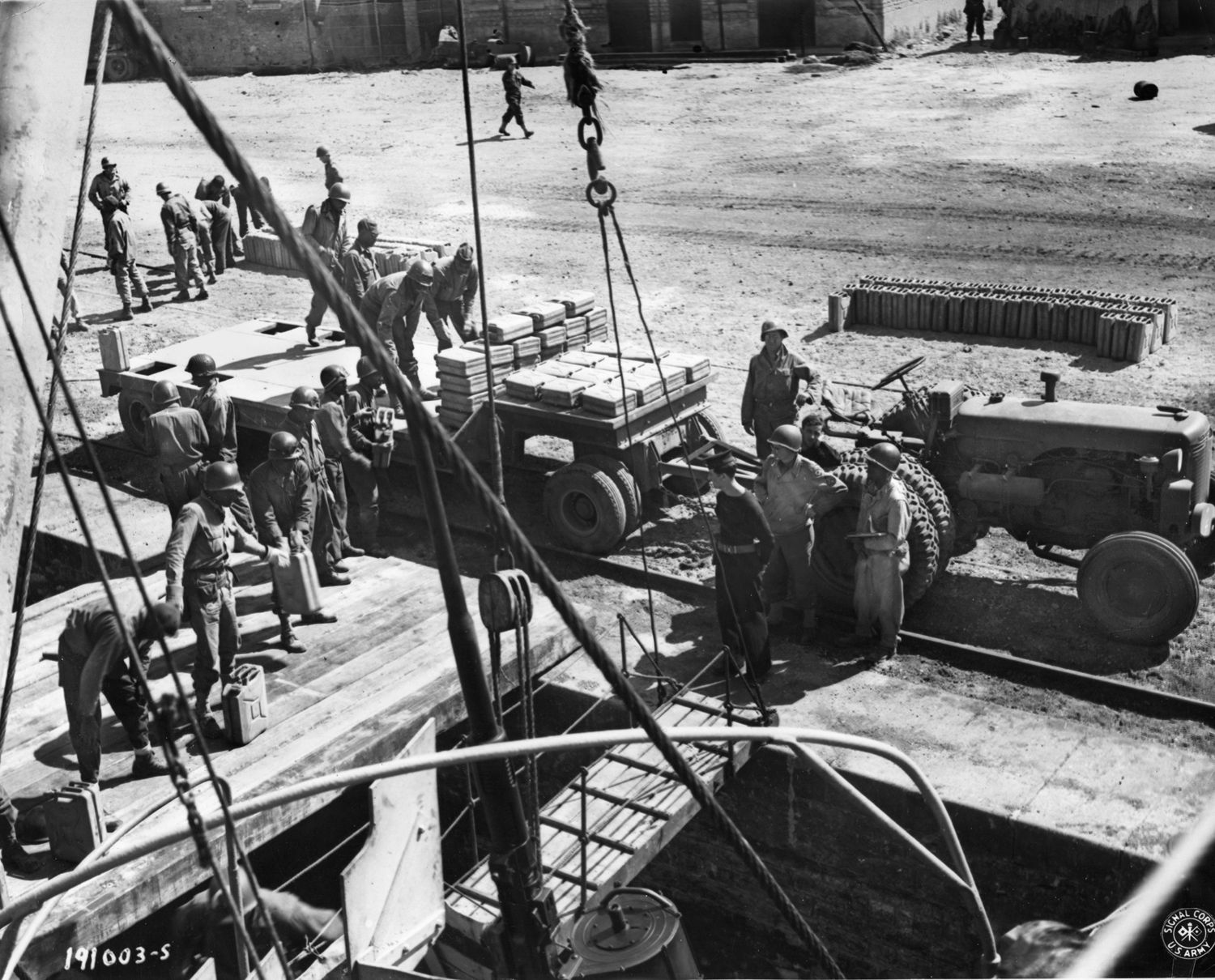

On D-Day, events occurred much as planned in terms of getting POL supplies ashore. Right behind the fighting men came the fuel and ammo. As the trucks and amphibious vehicles (DUKWs) rolled ashore, the supplymen began stacking their cargoes of five-gallon cans. They were placed in small, widely scattered dumpsites throughout the lodgment. This simple method of open storage made fuel supplies easily accessible. At the same time, this storage method rendered supplies less vulnerable to enemy attack. By the end of the first week, D+6, petroleum-supply companies were on hand to begin moving stores away from the beach as the troop buildup continued and the front line moved slowly inland.

By the end of June, the Normandy beachhead had expanded considerably, but Allied combat units were only advancing slowly through the hedgerow country in a bloody slugfest that would last several weeks. The Allies’ inability to score a quick breakthrough greatly impacted the supply situation. Since there was so little forward movement, stockpiles grew. Approximately 177,000 vehicles and more than a half million tons of supplies, had come ashore by D+21. At the same time, failure to capture Cherbourg as planned––and the enemy’s almost total destruction of the port’s facilities––meant that the proposed pipeline schedule had to be delayed. For the next few weeks, all POL requirements had to be met solely by packaged distribution, i.e., the five-gallon jerrycans.

The breakout from the Normandy beachhead finally occurred in the last week of July. Following a massive aerial bombardment on the 25th, General Omar N. Bradley’s First Army ruptured German lines near the town of St. Lô in an operation code-named Cobra. The next day, three armored divisions poured through the gap.

As the Allies broke out from the coast in late July, Lt. Gen. George S. Patton took command of the newly activated Third Army. By August 13, American spearheads had reached Le Mans, 90 miles from Paris (the French capital itself would be liberated on August 25).

After smashing German forces in the Falaise Pocket (August 12-21), Eisenhower authorized Bradley and Patton and British General Bernard L. Montgomery to cross the Seine in pursuit of the fleeing German Army. Eisenhower knew that this decision would impose a heavy burden on the Allied logistics system—that the task of keeping the troops supplied might exceed its capabilities. Logistic requirements were already strained by the speed with which the last 200 miles of advance had been covered.

Patton summed up the situation facing his army: “At the present time our chief difficulty is not the Germans, but gasoline. If they would give me enough gas, I could go all the way to Berlin!” As Patton was racing across France, Third Army was consuming an average of 350,000 gallons of gasoline a day.

Suddenly, the Allies faced a new set of problems.

Supply difficulties were complicated by the fact that the U.S. Army was supporting more troops than had originally been anticipated. The Communications Zone (COMZ) had expected to supply 12 divisions––a division in combat requiring 500 to 750 tons or more a day––in the first 90 days following the invasion and then only in the area west of the Seine. COMZ did not expect to support these forces beyond the Seine until after September; however, by late August, COMZ was supporting 28 divisions operating in France and Belgium, 16 of which were some 150 miles east of the Seine.

There was no shortage of supplies; they were just in the wrong places. Planners had also not foreseen Third Army’s penetrating into Lorraine and growing into a “large” force. It had been thought that Patton’s push would be a small, secondary effort south of the Ardennes to divert enemy resistance from the main Allied drive by Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges’s First Army, in the north. The situation was further complicated as large numbers of trucks were being used to haul equipment for the construction of fuel pipelines and to build depots.

Because of the rapidity and success of the American advance, the original logistics plan was modified to support Patton’s major thrust south of the Ardennes.

The invasion beaches had been expected to serve as the main point of entry to Europe for men and matériel for only about a month. By D+30, Allied planners expected to occupy and be operating the port of Cherbourg along with five smaller Normandy ports. But, by late July, nearly 90 percent of matériel was still arriving over the beaches and would continue to enter the ETO via those same beaches well into the fall when Antwerp was finally opened.

Although trucks were considered to be crucial to delivering supplies to the front, the logistics planners had assumed that trucks would not be used for hauling supplies over distances greater than 150 miles. They had not accounted for how long the French railway system would be out of action because of the success of the Allies’ pre-invasion air bombardment and the French Resistance’s sabotage efforts.

Supply requirements had been projected on the basis of anticipated troop strengths. The Army’s Motor Transportation Division assumed the use of standard truck companies, each operating a nominal 40 of 48 authorized 21/2-ton, six-by-six trucks (known as “Deuce-and-a-halves”). Calculations were made using 100 percent overloading to five tons, a single driver, and a maximum average daily range of 50 miles, thus giving a truck company a capacity of 10,000 ton-miles per day. Based on these calculations, it was proposed that 240 truck companies would be needed to support operations, but the War Department had allocated only 160.

The decision to cross the Seine and continue eastward without waiting to fully develop lines of communication and supply also constituted a major departure from previous plans. While the decision posed difficulties for logisticians, it presented a gamble senior commanders were willing to risk. Once across the Seine, the Allied forces fanned out, doubling the length of their front. With 90 to 95 percent of Allied supplies on the Continent still in base depots, the situation grew more critical with each passing day.

In late August, Eisenhower directed that most petroleum supplies go to Hodge’s First Army and Montgomery’s 21st Army Group. This action was to come at the expense of Patton’s Third Army.

When American forces reached Sens, southeast of Paris, on August 22, it became clear that additional road transport would be needed to stock the road-heads of the advancing forces.

The urgency of the situation called for drastic measures, but there was little time for thoughtful planning. An attempt was made to offset the shortage of trucks by pooling 90 Advance Section (ADSEC) quartermaster truck companies into a single organization—the Advance Section Motor Transport Brigade or ASMTB, under Colonel Clarence W. Richmond.

Allied planners met in a “brainstorming” session on August 23 to come up with a solution to the burgeoning supply crisis. Two of the principal planners were Lt. Col. Loren A. Ayers, chief of MTB (Motor Transport Brigade), who was in charge of gathering and training drivers and obtaining equipment, and Major Gordon K. Gravelle, of COMZ headquarters. The plan conceived of by Ayers and Gravelle called for pooling truck assets and facilities of COMZ and MTB. They also called for requisitioning trucks from other Army units. Vehicles were to be taken from anti-aircraft and artillery battalions, engineer companies, and infantry units awaiting transfer to the front. The decision to establish the operation was made by Brig. Gen. Ewart G. Plank, ADSEC, on the night of August 23. The Red Ball was established 36 hours later—the name “Red Ball” borrowed from a railroad term indicating a freight train that was to be given the right-of-way.

The first phase of the Red Ball Express began on August 25, initially running for five days with 76 truck companies using 3,358 trucks, mostly deuce-and-a-halves. The prime aim was to deliver 75,000 tons of supplies, plus quantities of gasoline, to the Chartres-La Loupe-Dreux area, a distance of 125 miles from St. Lô, by the beginning of September. The complete truck route was not determined in detail until the afternoon of August 27. The limited width of the roads in Normandy caused Richmond and Ayers to demand that a one-way system be implemented.

There was little precedent for a large-scale motorized supply operation such as the Red Ball Express. The Transportation Corps had used a somewhat similar, but limited, effort as it moved supplies from dumps in Britain to Channel ports prior to D-Day. Before the invasion, the Army had considered but never tested a long-haul supply operation.

By the planned end of the first phase of the Express, 132 Army truck companies with 5,958 trucks had been employed. By September 1, when the first phase of the operation was supposed to have been completed, the French railway system was still not ready to meet the needed volume, so the target for road deliveries was increased accordingly. The operation was extended until September 4, delivering 89,939 tons of supplies to depots in the Chartres-La Loupe-Dreux triangle.

To facilitate operations, MTB officers established traffic-control points (TCPs) that operated around the clock at principal intersections and in cities, towns, and villages. TCP personnel regulated convoys, or any other vehicles, to ensure that Red Ball convoys had the right-of-way. TCP troops recorded passing convoys, logged their destinations and weights. TCPs also provided rest areas where trucks refueled, made minor repairs, and drivers received hot coffee and meals. TCPs were established at St. Lô, Vire, Domfront, Alençon, Montagne-au-Perche, La Loupe, Chartres, Nogent-le-Rotrou, Bellême, Mamers, Villaines-la-Juhel, Mayenne, and Mortain.

Some trucks were also required to travel north to the Normandy Base Section depot in the beachhead area, and even as far as Cherbourg, to collect cargo. But the control point was established back at St. Lô, where the convoys were to be assembled and dispatched.

Traffic control was a major challenge as MPs did their best to ride herd on the convoys. There were hundreds of miles of highway to patrol, intersections to manage, and bridges to guard. Despite their efforts, entire loads of material went missing. In all, about 2,000 trucks were reported stolen.

The strain on personnel and equipment quickly became apparent. As the word spread among combat units and in news stories, the drivers attempted to live up to the growing reputation of the operation as they regularly began to ignore speed and weight limits, and their own fatigue. No trucks were to be idle due to the lack of drivers. Besides a driver shortage, the Express also faced problems of vehicle maintenance and increasing truck mishaps. As the number of single-vehicle accidents climbed, the Army began assigning relief drivers. Some 5,600 men were transferred to the 140 truck companies involved in the operation. Unfortunately, many of them had never driven a truck before.

In early September, General Bradley believed that an all-out effort would smash the Siegfried Line defenses and reach across the Rhine within a week, and he urged his commanders to pursue the enemy relentlessly.

Bradley’s plan was a two-pronged thrust north and south of the Ardennes. The northern thrust, using First Army, would drive east from Brussels through Liège and Aachen to Cologne. The southern thrust, with Third Army, would jump off from the Meuse River bridgeheads and move east to the Rhine through the Saar toward Frankfurt. Augmenting both thrusts would be V Corps, which would fill the gap between the two armies.

However, Eisenhower was concerned that Bradley might be trying to do too much too soon given the logistics situation. But offensive operations could not be denied in the face of the pressure to defeat the Germans as quickly as possible.

As a result of Eisenhower’s decision to permit Patton to aggressively pursue the retreating German forces, it was decided to expand logistic operations. The new operation, phase two of the Red Ball Express, was extended eastward to Soissons and Sommesous.

It was hoped that Patton’s forces could achieve a quick victory and that the Red Ball operation would be successfully completed. But fuel consumption for Third Army was now reaching close to a million gallons a day.

As the Red Ball was extended beyond Paris into eastern France in the second and longest phase of the operation, two new truck routes that looked on a map like a giant race track were created. They branched north and south to serve an ever-expanding front stretching from Belgium to Alsace.

The northern leg skirted Paris, passed through the suburb of St. Denis, and terminated at Soissons, 30 miles northeast of Paris. On the return leg it ran south to Château Thierry, Coulommiers to Fontainebleau, and back to Chartres. The southern leg of the extended Red Ball ran southeast to Melun, Fontenay-Trésigny, and Rozay-en-Brie, then east to Esternay and Sommesons. The return route ran through Arcissur-Anbe and Nogent-sur-Seine and back to Fontainebleau and Chartres. The northern route was later extended to Hirson, France, the southern to Metz and Verdun.

With the extension of the Red Ball, its length was nearly tripled. The round-trip length from Normandy to Hirson was 686 miles, the southern route 590 miles.

By early September 1944, with the First Army’s advance into Belgium, and as Hodges prepared to move into Germany, Red Ball trucks were driving as far as Liège, where a massive supply depot was being prepared. Logistics units were put to the test as Montgomery’s 21st Army Group faced a crisis. Some 1,400 British trucks were out of service due to faulty engines, and replacement engine parts were found to be defective. At the same time, Montgomery believed that if his bold new operation, Market-Garden, could create a bridgehead over the Rhine, his armies could make a dash for Berlin and end the war in 1944. The logistics support operation for this was code-named the “Red Lion Express.”

The task of supporting the operation fell to the U.S. Army. Acceding to Montgomery’s requirements, Eisenhower ordered the daily transport of some 500 tons of supplies 300 miles from Bayeux, in the Normandy base area, to Brussels—17,000 tons in all. This placed an additional burden on the Red Ball’s resources at a time when there was a critical shortage of trucks.

COMZ began scouring units for nonessential vehicles. Trucks and drivers were requisitioned from evacuation hospitals, salvage and repair companies, engineering units, signal companies, and maintenance units. Ten trucking companies with some 340 vehicles came from antiaircraft units. Two engineer general-service regiments were reorganized into seven truck companies and a chemical smoke-generating battalion was organized into four truck companies. The largest number of trucks and drivers came from idled infantry divisions awaiting transfer to the front. Forty companies with 1,500 trucks were pulled from three divisions bivouacked in Normandy—the 26th, 95th, and 104th Divisions initially, and later from elements of the 84th, 94th, and 104th Divisions. In all, 61 provisional truck companies were created.

On any given day, 899 trucks were operating on the Express, driving an average 54-hour roundtrips. The round-the-clock movement of thousands of trucks necessitated a strict set of rules. The trucks were to move in complete company-unit convoys. A company’s full strength was 48 vehicles, but 40 was used for planning purposes, allowing for maintenance and breakdowns. Convoys of no fewer than five trucks were allowed.

Vehicles in a convoy were to maintain 60-yard intervals. The convoys were divided into “serials,” each with a minimum of five trucks. The trucks were numbered to indicate position in the convoy. A one-minute interval was to be kept between serials, and two minutes between convoys. A jeep generally ran at the head and rear of each convoy.

The maximum speed limit, although widely disregarded, was set at 25 miles per hour. Drivers were not permitted to overtake or make unauthorized stops. A 10-minute break was scheduled every two hours at 10 minutes before each “even” hour to allow loads to be checked and readjusted, for minor repairs, and to allow drivers a break.

Operations continued through the night, and, in the absence of enemy air activity, the crews were permitted to use full headlights.

For defense against possible air or ground attacks, some of the trucks were outfitted with .50-caliber machine guns, but generally the drivers carried only carbines for personal defense.

As part of the operation, eight sites, or towns, were designated as repair facilities and for staging replacement vehicles along the Red Ball Express routes. These included St. Lô, Vire, Alençon, Montagne, Chartres, Nogent-le-Rotrou, Mayenne, and Mortain. The routes were also regularly patrolled by service and recovery units operating out of these facilities. Disabled vehicles were to be moved to the side of the road where they were either repaired by roving maintenance units or removed to rear-area depots for repair.

The transport effort required the coordination of various service support branches. Engineers maintained roads and bridges, Military Police (MPs) ran checkpoints directing traffic, and matériel handlers and petroleum specialists were ever present along the route and at forward-area truck-heads.

The trucks were not empty on the return leg of their trips. Salvaged shell casings, war debris of various kinds, wounded soldiers, POWs, and the remains of the dead were all carried back from the front for processing.

Routes were marked with red circle signs, the “red ball.” Only trucks with a matching red ball insignia were permitted to use them. The special road markers and MPs were intended to keep the trucks on the correct roads.

Bivouac areas were set up along the Express roadways. One was at Alençon and another near Chartres. The transportation hub and rest areas around Alençon were the home base for some 100 truck companies and 22,000 service personnel. The area provided quarters, mess facilities, and medical care for the men along with vehicle-maintenance operations.

Much of the fuel transported was still in five-gallon containers––jerrycans. However, at the very height of Red Ball activities, a severe shortage of jerrycans threatened fuel deliveries. The cans had been carelessly discarded and littered roads from the beachhead to the front. The Army’s Chief Quartermaster offered a reward to French civilians to help round up the containers, but a shortage remained until more cans could be manufactured and delivered.

The Red Ball Express also faced an inherent problem in terms of diminishing returns. As supply routes lengthened, the Red Ball required increasing amounts of gasoline to run its own trucks, reaching 300,000 gallons per day.

Beside the long hours and distance covered, there was also the threat of hijacking and theft. A jerrycan of gas could fetch $100 on the Black Market.

Once Paris was liberated the demand for gasoline became astronomical. Millions of gallons of U.S. Army gasoline disappeared into Paris, a good deal of it taken by AWOL soldiers who also disappeared into the city as the Americans advanced beyond the Seine. In the fall of 1944, an estimated 20,000 American soldiers were reported to be AWOL in France. AWOL soldiers needed cash to survive and found easy money in the Black Market. Many of these soldiers either joined existing underworld gangsters or formed their own gangs.

The most common method of acquiring gas was petty theft, where gang members cruised Paris streets and stole jerrycans off unattended vehicles. The more brazen of the gangs simply drove up to fuel dumps with dozens or even hundreds of empty jerrycans and asked for gas. Because of the speed of the Allied advance, gas dumps got in the habit of servicing GIs without question. There was no time to determine if a soldier was telling the truth, plus there was no proper system of acquisition in place. The situation was ripe for theft and abuse.

The gasoline gangs were highly organized, some along the same lines as military units with promotions, passes, and duty rosters. The boss of one gang was an AWOL medic who dressed as an MP lieutenant and rounded up other AWOL soldiers. He induced, threatened, or blackmailed soldiers to become part of his gang.

The AWOL soldiers made so much money so fast that it eventually became the undoing of many of them. Criminal Investigation Division (CID) agents assigned to break up the gangs caught many of them when they tried to send home thousands of dollars in War Bonds or postal money orders. Others were arrested when they flashed large wads of bills in cafés or were caught driving expensive cars. Many were caught in AWOL roundups. Some were given up by the French—jilted girlfriends, jealous boyfriends, and Parisians who hated seeing the Americans exploiting the city’s needs.

As with any and all armies, there were the normal weaknesses and temptations. Transportation operations had to deal with drunkenness and unauthorized absences in truck units. There was also the distraction of women. And there were reports of drivers dropping out of convoys and loads being sold.

Despite the many problematic issues, in a message to the members of the Red Ball Express on October 1, 1944, General Eisenhower stated, “To you, the drivers and the mechanics and your officers, who keep the Red Ball vehicles constantly moving, I wish to express my deep appreciation. You are doing an excellent job.”

Of the more than 50,000 men who were employed on the Red Ball Express, some 40,000 were African Americans. All of these men were initially drawn from Quartermaster truck companies.

African Americans made up just over 10 percent of the U.S. Army during World War II, but almost 21 percent of service units. Approximately 73 percent of the transport companies of the Motor Transport Service in the ETO were made up of black soldiers.

In addition to driving trucks, African American soldiers made up engineering units that kept open the supply routes, maintenance companies looking after vehicles and depots, and three-quarters of the stevedores in port battalions unloading ships delivering supplies at French ports.

[It should be noted that other African Americans served in the few segregated ground-combat units in Europe such as the 92nd Infantry Division, which fought in Italy. They also saw combat in segregated artillery battalions, as well as segregated armored units, including the 84th, 827th, and 761st Tank Battalions, the latter distinguishing itself during 183 days in combat.]

By early 1945, increasing losses in American infantry regiments had reached crisis proportions. Thirty thousand white soldiers were hurried to Europe. Fresh from training, they were rushed into combat units only to add to the casualty lists. The shortage of riflemen worsened. Eisenhower offered amnesty to men in the stockade if they would serve, but there was little response. Finally, Ike looked to the black service units, offering them the chance to fight. They were to be integrated into infantry divisions, but only by platoons. Twenty-five hundred blacks volunteered immediately. Because of the prohibition of blacks being in charge of white soldiers, only privates and PFCs were accepted. As a result, many black soldiers took a reduction in rank to be included. The platoons were distributed among the Sixth and Twelfth Army Groups, though not to Third Army.

In reviewing the logistic transport operations, ADSEC identified deficiencies in road maintenance, handling supplies, traffic control, communications along the extended routes, and vehicle maintenance. Driving was often extremely reckless and accidents were common. ADSEC concluded that convoys should have been smaller than company size—reduced to 13 to 16 vehicles. But the Red Ball had been initiated with minimal training and little preparation. As a result, there were delays in loading and unloading supplies, extending convoy turn-around times.

Fortunately, during the first week of September 1944, the port of Antwerp finally fell into Allied hands and, as soon as repairs could be made, would become the principal port for bringing supplies into the ETO. It would also put the Red Ball Express out of business.

When the Red Ball program finally ended in mid-November 1944, Express truckers had delivered 412,193 tons of food, gasoline, oil, lubricants, ammunition, and other essential supplies, moving an average of 5,000 tons a day.

While the Red Ball Express may have been the most famous, it was only the first of a number of logistic operations that occurred during 1944-45 in Western Europe. Besides the Red Lion Express, September 13 to October 12, other operations followed in various sizes and scope, including the Little Red Ball Express, which operated for only a month beginning December 15, transferring 100 tons of cargo a day from Cherbourg to Paris.

Another operation of short duration was the Green Diamond Express, running from October 10 to November 1, using approximately 600 trucks to move supplies from Normandy depots to railheads at Avranches and Dol-de-Bretagne. The White Ball Express, from October 6, 1944, to January 6, 1945, cleared the ports of Le Havre and Rouen by transferring supplies to railheads at Paris, Beauvais, and Compiegne.

Two larger supply-transport operations of longer duration included the ABC Express, which moved over 244,000 tons from Antwerp to Brussels, Liêge, Charleroi, and Mons, from November 30, 1944, to March 26, 1945, providing supplies to the U.S. First and Ninth Armies and to the British-Canadian 21st Army Group. The second and largest of all operations was the XYZ Express, which ran during the last days of the war in Europe, from March 25 to May 31, 1945, delivering nearly 872,000 tons of supplies from Liêge, Duren, Luxembourg, and Nancy into Germany, as it supported the U.S. First, Third, Seventh, and Ninth Armies during the final drive into Germany.

The Red Ball had achieved its greatest success during the first chaotic weeks of operation. The Transportation Corps’ original plans were to transport 75,000 tons of supplies, excluding bulk POL, to the Chartres-La Loupe-Dreux area by September 1. By September 5, it had delivered 88,939 tons.

For over two months, the Red Ball Express transported petroleum and other supplies up to 400 miles. But success came at a price. Round-the-clock driving put a strain on personnel and equipment. Continuous use of vehicles led to their rapid deterioration and resulted in a drain on parts and labor. The situation was aggravated by driver abuse, including speeding and overloading. Fatigue also led to an increased number of accidents, and even instances of sabotage where drivers disabled their vehicles in order to get some additional rest.

The Red Ball Express involved endless hours of dull, hard, and many times dangerous work. Nonetheless, it captured the media’s attention, and had the effect of placing supply and service personnel in the spotlight.

The need for the Red Ball Express arose from the mismatch between the supplies piling up at the beachheads and the needs of the unexpectedly rapidly advancing Allied armies. The situation allowed little time for advance planning or preparation. The Express was, as one observer noted, “largely an impromptu affair.” Yet, it proved to be an outstanding success to the Allied victory in Europe.

As General Omar Bradley put it, “Logistics, this was the dullest subject in the world. But logistics were the lifeblood of the Allied armies in France.”

There is a Signal Corps 1944 Film about the RBE. It’s not very well known because of the title they chose in 1944: Rolling to the Rhine. Most of the photos published in the article are cuts from that movie.

Doc Snafu

eucmh.com