By John Protasio

World War I was a total war; Nearly every person and resource was caught up in the conflict. The war at sea would be crucial— the British were not self-sufficient in food and resources. Much of their food and matériel came overseas from the United States and Latin America. Manpower from Canada and later the United States had to cross the ocean as well.

The British merchant marine would play a critical role in the war. Among the ships that would take part in the war were passenger liners. In the years immediately before the war, the Atlantic passenger trade had skyrocketed and by 1905, the immigration tide to the United States exceeded one million a year. To handle these trends, numerous passenger liners were constructed, some of exceeding 30,000 tons in weight.

Some liners were pulled out of civilian service almost immediately after the war began. One of the first was the Cunard liner, Carmania, which left New York City with a load of passengers shortly after

hostilities got under way. When she arrived in Liverpool, the British government took her into service. Armored plates were riveted onto the ship, sand and coal bags were placed strategically for protection, and her hull was painted a military gray. Eight 4.7-inch guns were placed on deck. She was ready for war.

Carmania was sent to Halifax for patrol duty, but one day out she was reassigned to Admiral Christopher Craddock’s fleet in the South Atlantic. She arrived in Bermuda on August 23, 1914, and took on coal. Shortly after joining Craddock’s squadron, the liner was sent to search out secret depots the Germans established in the South Atlantic. Three weeks later, Carmania came upon Trinidad Island, 700 miles east of Brazil, where her officers and lookouts spotted Cap Trafalgar of Germany’s Hamburg-Amerika Line. She had been armed with two 4-inch guns and six pom-poms, as well as machine guns. The liner was disguised as a Castle Line ship.

The crew of the German liner saw the British at about the same time as the Britons saw Cap Trafalgar. The German ship began to pick up speed in an effort to engage the enemy. The British liner raced to the Teutonic vessel at 16 knots. The battle began at 12:10 and lasted about 80 minutes, with Cap Trafalgar getting the worst of it. The German liner began to list and burn out of control. Her captain headed for land in hopes of beaching his command, but it was too late. The ship sank before she could reach the shallow waters. According to one of the crew of Carmania, the British sailors cheered.

The liners that were allowed to continue serving as passenger-carrying vessels were sometimes caught up in the war. On March 28, 1915, the British steamer Falaba was en route to West Africa from Liverpool. One day out, she encountered the German submarine U-28, commanded by Baron von Forstner. The sub signaled Falaba to “stop and abandon ship.” Falaba attempted to flee, but the faster U-boat caught up with her. There is some conflict as to what happened next. The Germans claimed the British crew began transmitting wireless distress calls and shooting up rockets. Von Forstner decided that he could wait no longer and fired a torpedo. Falaba sank and 104 people, including an American, Leon Thrasher, perished.

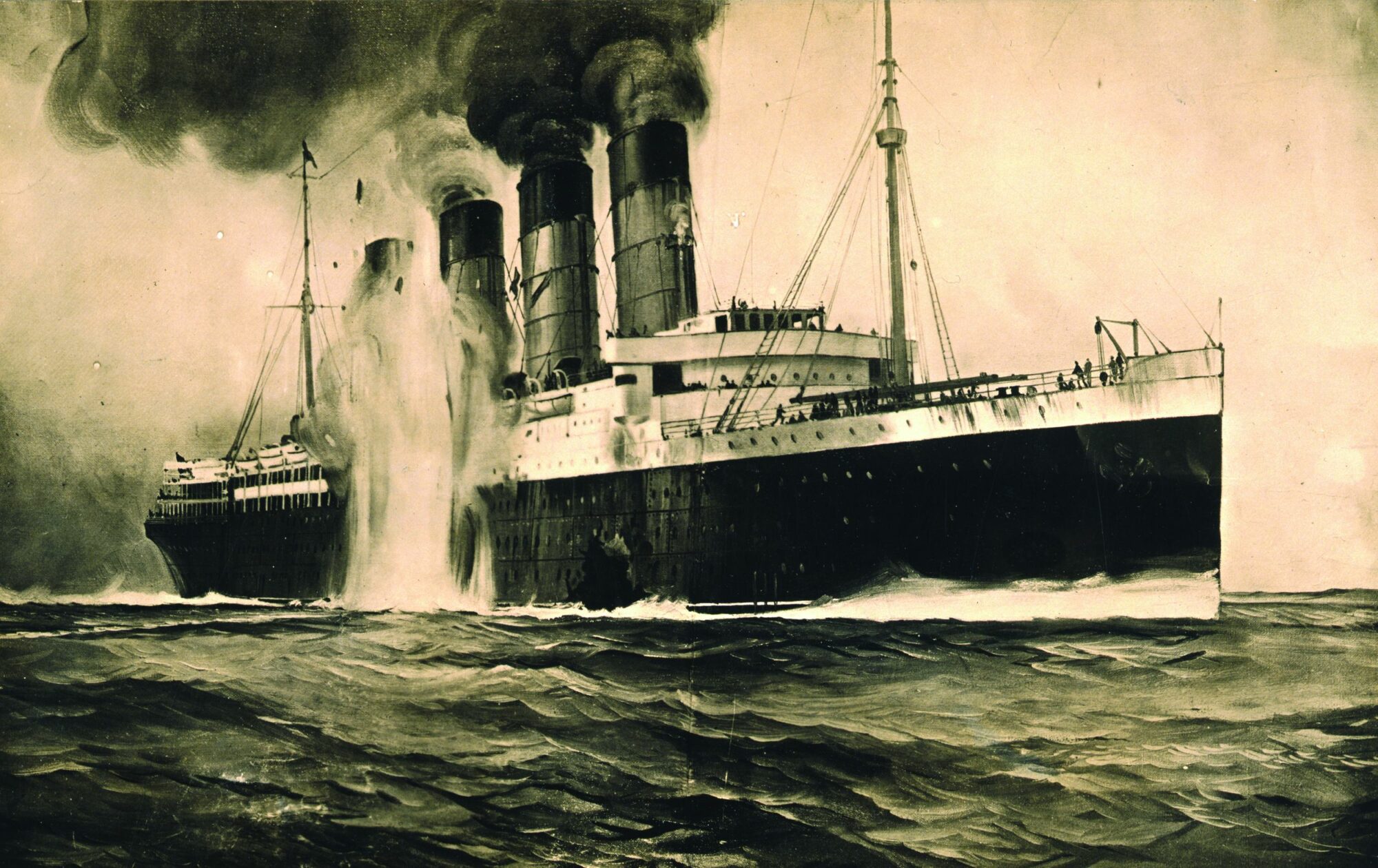

The Germans publicly warned that they would sink passenger ships they suspected of carrying arms and supplies to Great Britain. They even published a newspaper advertisement insisting that passengers using British ships “do so at their own risk.” On May 1, 1915, the Cunard liner Lusitania departed from New York City, bound for Liverpool with 1,257 passengers (197 Americans) and a crew of 702. Among the items stored in her cargo were cheese, lard, bacon, oysters, and sheet metal as well as 42,000 cases of rifle ammunition and 100 cases of empty shrapnel shells.

By May 7, Lusitania was a few hours from Liverpool. She received numerous wireless reports of enemy submarines in the area, including one that read, “Make sure Lusitania gets this.” Later that day, the liner was off Old Head of Kinsale. To be certain of his navigation, the ship’s captain, William Turner, began to conduct a four-point bearing. Not far away, Captain-Lieutenant Walther Schwieger, the commanding officer of U-20, was scanning the horizon for prey. He spotted the Cunarder, dived, and came within 700 meters of the luxury liner. At 2:10 pm, Schwieger gave the fateful order to fire.

The torpedo struck Lusitania on the starboard side and exploded. A split second later, a second explosion rocked the liner and she immediately developed an ominous list to the starboard. Passenger Oliver P. Bernard saw it coming. He was seated in a deck chair when he noticed the sub’s periscope, then he observed a long, white streak of foam making its way to the ship. Realizing that it was a torpedo, Bernard covered his eyes.

Dr. Ralph McCready was on deck when he heard “a terrific explosion.” He hurried to his cabin and put on his life belt, then returned to the boat deck. Two sisters, Agnes and Evelyn Wild, who were eating in the dining room when they heard the explosion, rushed outside and clung to each other, “determined not to be separated,” Agnes recalled. Members of the crew assisted the passengers. Eighteen minutes after the torpedo struck, Lusitania sank. Of the 1,959 people on board, 1,201 were lost, including 124 Americans.

There was an immediate worldwide uproar over the incident. Many people in both Britain and the United States blasted Germany. “It is a deed for which a Hun would blush, a Turk be ashamed, and a Barbary pirate apologize.” editorialized one newspaper. American President Woodrow Wilson was also outraged. He dispatched no fewer than three notes over the incident, warning that future attacks on passenger ships would be viewed as a “deliberately unfriendly act.”

The German government responded by claiming that Lusitania was armed and carrying munitions on her final voyage. Oceanic explorer Robert Ballard, who examined the wreck in the mid-1990s, found no guns on board Lusitania. The vessel was, however, carrying 42,000 cases of rifle ammunition, which could be considered military cargo. Ballard concluded that the second explosion was the result of coal dust igniting after the first blast.

As for the charge that the British deliberately allowed the ship to be torpedoed in order to embroil the United States in the war, the absence of armed escorts is cited by German apologists as part of the evidence. However, there were only so many warships in the British Navy, so some ships had to be left on their own. Lustiania, with her superior speed, was viewed as being immune from submarine attack. Furthermore, the British Admiralty had gone out of its way to warn the liner before her demise.

On August 19, 1915, another passenger ship, the White Star liner Arabic, was torpedoed and sunk several hours out from Liverpool. Her captain, William Finch, had been concerned for his command in the wake of the discovery of two sticks of dynamite in one of the staterooms during a previous voyage. The culprit was not found, but German saboteurs could not be ruled out.

Unlike Captain Turner of Lusitania, Finch took the U-boat menace seriously. He avoided headlands and steered a mid-Channel course. The captain traveled at top speed (16 knots) and zigzagged. Then, at 9:15 on the morning of August 9, Finch and his men saw the British steamer Dunsley. Finch could tell that something was amiss—two of Dunsley’s lifeboats were waterborne. She was under attack by German submarine U-24.

Suddenly, Finch saw an object underwater coming straight for his command. There was no doubt in his mind that it was a torpedo. The captain ordered the engines stopped and put astern, but it was too late. The torpedo struck the liner. In the next instant, Finch heard a “terrible explosion, so loud I never heard anything like it.” Immediately, the ship developed a frightening list.

Arabic’s crew sprang into action, filling and lowering lifeboats. Finch was determined to go down with his ship. From a lifeboat, passenger J. Edward Usher noticed the captain: “His face was calm and pale as if he was facing death with the grim resolve not to desert his post.” As Arabic began to sink, lifeboats tore from their fastening and floated away. Usher heard “a sizzing roar.” Nine minutes after the torpedo struck, the liner sank. Rescuers picked up 379 survivors, including the captain. Forty-four people were lost in the attack, two of them Americans.

Some British liners were converted into hospital ships. The war effort in the Mediterranean was resulting in thousands of men being wounded. The Admiralty employed passenger ships from the Union Castle Line. Typical ships were 6,000 to 8,000 tons, however, and could not carry many wounded. Consequently, the Admiralty took over the larger passenger ships Aquatania, Mauretania, and Britannic.

Mauretania was under the command of Arthur Rostron, who in 1912 had become famous for rescuing the survivors of Titanic. Mauretania, sister ship of the ill-fated Lusitania, was painted with red crosses. Unlike other ships, which traveled at night with few lights, the ship would be ablaze with lights at night so that her red crosses could be seen. The hospital ship carried 40 medical officers, 72 nurses, and 120 orderlies. There was an X-ray room and an operating theater.

On the way to war, Mauretania stopped off at then-neutral Italy. While there, Rostron invited Germans and neutrals aboard to inspect the ship to make certain that his command was a bona fide hospital ship. Every crew member aboard was called forth for inspection and packages were opened. Rostron went as far as to allow his guests free access to visit any part of his ship and to ask any questions. It worked. Mauretania was not attacked.

By far the most famous hospital ship in this war was the White Star liner Britannic. Launched in February 1914, she was also a sister ship of Titanic. Britannic had accommodations for 3,000 patients. The liner had made five complete voyages as a hospital ship, then, in November 1916, she began her sixth voyage. She had on board 22 surgeons, 77 nurses, and 290 orderlies, along with 1,065 passengers.

Her captain, Charles Bartlett, could not be certain if the Germans would respect the Britannic’s status as a hospital ship. His fears proved well founded. At 8:12 on the morning of November 21, there was a great explosion. Britannic shook and began to list dangerously. Bartlett tried to beach the ship, but the steering gear failed. The crew directed their efforts to abandoning ship. Lifeboats were lowered, but unfortunately the ship’s propellers were still turning. Three boats came too close to the rotating screws and were smashed.

For 55 minutes after the explosion, the liner remained afloat while listing badly. Then, at 9:07, the great hospital ship foundered, taking 21 people down with her. At 48,158 tons, she had the dubious distinction of being the largest ship lost during the war.

Britannic may have been the victim of a mine instead of a German U-boat. A search of German archives reveals no record of a submarine attack in the area, but several mines had been set in the vicinity.

Some British liners were converted to troop transports. After her service as a hospital ship, Mauretania was made into a troop transport in 1918. Once again, Rostron stood on her bridge. The liner carried about 5,000 troops per voyage—in total about 35,000 American troops to France. By far the most famous troop transport was Olympic, which participated in the Dardanelles campaign. During that time, she rescued 34 survivors of Provincia, a French ship that had been torpedoed by an Austrian submarine.

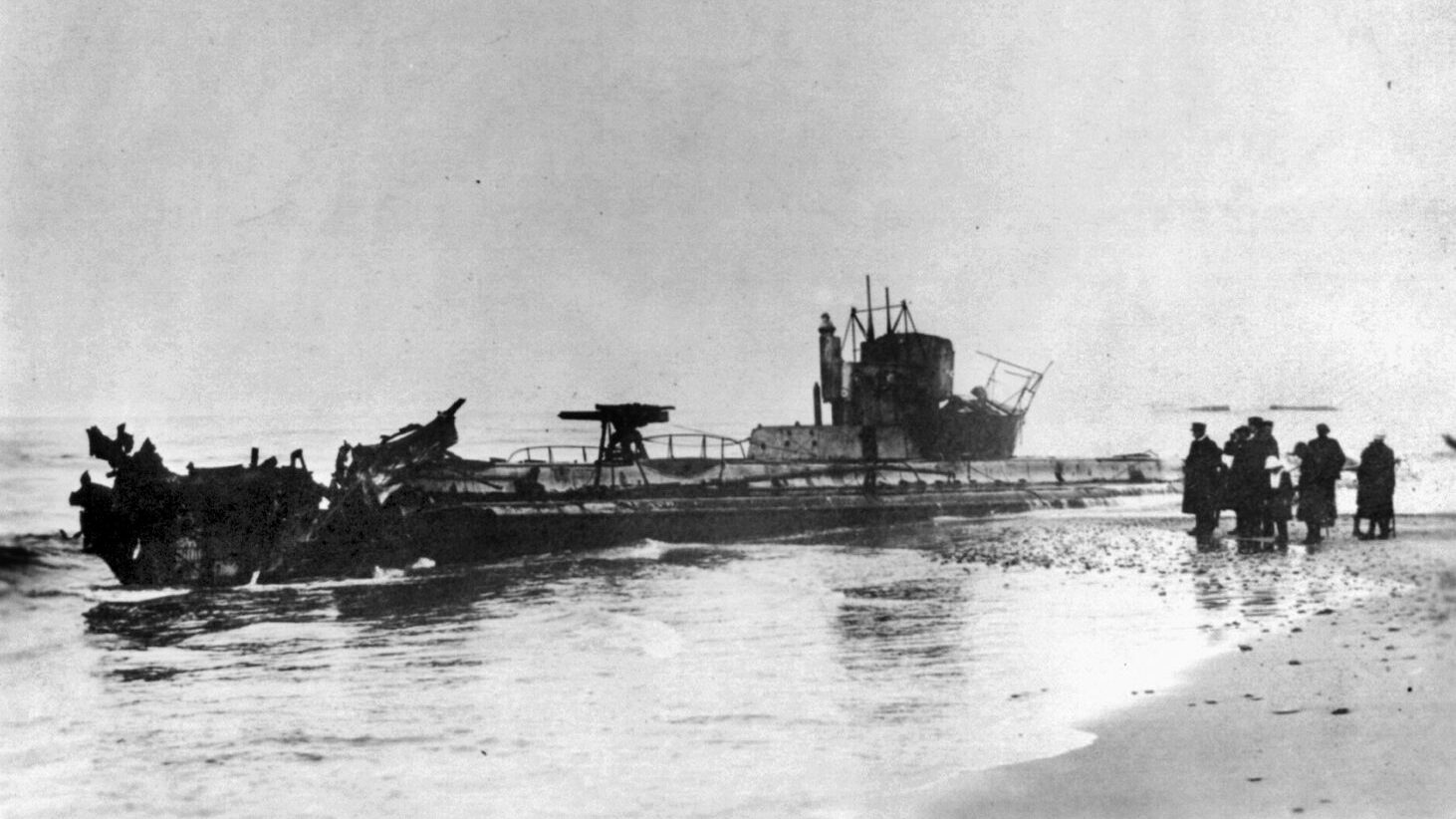

During the war, Olympic sailed 184,000 miles as a troop transport and carried more than 120,000 troops. She successfully evaded three submarine attacks. Then on May 12, 1918, came her fourth encounter. Olympic was in the English Channel to rendezvous with four British destroyers. At 3:55 am, lookouts spotted a submarine surfacing about a half mile away. The liner, which was armed with two guns, opened fire while ship’s captain Bertram Hayes turned toward the U-boat to ram it. There was a thud, and the liner vibrated slightly as she collided with the hapless U-boat. “Well, Thompson,” Hayes said to his assistant, “there’s forty of the brutes gone to hell.” Miraculously, there were survivors, but the submarine, U-103, was totally lost.

A few months later the armistice took place. Defeated Germany was handed harsh terms in the settlement on May 7, 1919, ironically the fourth anniversary of Lusitania’s sinking. Germany’s luxury liners were taken over by the British and Americans. Imperator was renamed Berengaria and given to the Cunard Line. Bismarck was handed over to the White Star Line, where she was renamed Majestic. Vaterland was given to the Americans and called Leviathan.

During World War II, Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth would transport thousands of British troops. As late as 1982, Queen Elizabeth II would carry troops to the Falklands, continuing to demonstrate the importance of merchant ships, including passenger liners, in time of war.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments