By Al Hemingway

They called him “Beetle.” He could be gruff and downright insulting at times to his subordinates. New officers joining his staff cringed when they had to go in and “meet the old man.” Despite his shortcomings, Walter Bedell Smith was just the kind of officer General Dwight David Eisenhower sorely needed to run his command staff. Smith was also the perfect choice to run interference between Ike and the British, who did not always see eye to eye on the numerous issues during the conflict. Eisenhower could be indecisive at times. But Smith was his voice of confidence in dealing with the seemingly endless matters that confronted him from their association in the Mediterranean Theater in 1942 until war’s end in 1945.

In his new book, Beetle: The Life of General Walter Bedell Smith (University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2010, 1,070 pp., photos, maps, notes, index, $39.95. hardcover), author D.K.R. Cresswell leaves no stone unturned in recapturing the spirit of the man who stood behind Eisenhower to offer him hope and encouragement during his darkest hours in the war.

In his new book, Beetle: The Life of General Walter Bedell Smith (University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2010, 1,070 pp., photos, maps, notes, index, $39.95. hardcover), author D.K.R. Cresswell leaves no stone unturned in recapturing the spirit of the man who stood behind Eisenhower to offer him hope and encouragement during his darkest hours in the war.

Born in Indiana in 1895, Smith wanted to be a professional soldier from an early age. He joined the Indiana National Guard in 1911. Little did he realize that he would not hang up his uniform until 42 years later. He received his commission in 1917, departed for France with Company A, 1st Battalion, 39th Infantry Regiment, where he saw action in the Aisne-Marne Offensive, and was wounded.

While Smith recuperated in the hospital, a decision was rendered by the senior staff that would alter his career in a positive manner. The high command ordered General John J. Pershing to send 30 officers for staff duty in Washington, D.C. Infuriated because he did not want to break up his inner circle, he ordered that a records search be made of any junior officer with staff duty experience and that they be sent instead. Smith’s name came up because he had done some staff work with the National Guard. Before long, the newly promoted 1st lieutenant was U.S. bound.

From there, Smith was transferred to the 2nd Infantry Regiment, which relocated to Fort Sheridan, Illinois, in 1921. The following year was a turning point for Smith. He became aide-de-camp to Brig. Gen. George Van Horn Moseley, the commander of the 12th Infantry Brigade. Moseley was impressed with the young officer and gave him excellent fitness reports. He saw firsthand Smith’s unique style of operating a staff and having it run smoothly. “They don’t make ‘em any better than Smith,” Moseley said.

During the Depression years, Smith was an instructor at the U.S. Army Infantry School and then attended the Command and General Staff School. After nine years as a lieutenant and several more as a captain and a major, Smith received his silver oak leaves in 1939. As lieutenant colonel, he returned to Washington to be Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall’s assistant to the secretary of the general staff. Marshall and Smith had also become friends while at the Infantry School and, like the others, Marshall was impressed with Smith’s abilities as a chief of staff.

Smith was on the fast track, and, by February 1942, he had earned his first star and set out to organize a combined chiefs of staff group. Not long afterward, Smith was promoted to major general, and in September 1942, he took charge of the Allied Forces Headquarters, as its chief of staff.

From 1942-1945, Smith work tirelessly for Eisenhower. He represented Ike on many diplomatic missions, one which included meetings with Italian officials to draw up an armistice between the two countries. Smith traveled to America and represented Eisenhower in conferences with President Franklin Roosevelt as well.

Smith also was the go-between, smoothing the waters of controversy that continually arose in Allied headquarters. Disagreements surrounding the invasion of Sicily, the Normandy invasion with its myriad of problems from supply to manpower, and the landings in southern France several months after D-Day were just a few of the quarrels Smith diffused.

Smith’s penchant for hard work and driving himself past his physical limits took its toll. He constantly suffered with bleeding ulcers and once even disobeyed Ike and left the hospital before being properly discharged.

When Germany surrendered, it was Walter Bedell Smith, representing the United States, who signed the surrender document. After the war, Smith held a variety of posts in the Truman administration, including Ambassador to the Soviet Union and Director of Central Intelligence. He was also the Undersecretary of State when his former boss, Eisenhower, was elected president in 1952.

When Smith passed away in 1961, Eisenhower said this: “A very good soldier of France [de Lattre de Tassigny] once assured me that my place in military history was secure since the only requisite for an enduring spot in the history of battles was wisdom in selecting a Chief of Staff. He went on to say that no one in World War II was quite as wise, or at least as fortunate, as I in this regard. And of this circumstance I would of course be forever the beneficiary.”

Orde Wingate: A Man of Genius 1903-1944 by Trevor Royle, Frontline Books, London, UK, 2010, 384 pp., photos, notes, index, $32.95, paperback.

Orde Wingate: A Man of Genius 1903-1944 by Trevor Royle, Frontline Books, London, UK, 2010, 384 pp., photos, notes, index, $32.95, paperback.

To say Orde Charles Wingate was a unique individual is an understatement. Lauded by some, such as Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who called him a “man of genius,” and despised by others, such as Lt. Gen. Joseph “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell, the American commander in the China-Burma-India Theater, Wingate had unorthodox ideas.

Wingate was born to be a soldier. He spent his early years in India until his father retired from the British Army, when he was just two years old. The family relocated to Great Britain and the children were raised in an extremely regimented lifestyle that included long hours of studying the Bible. As a child, Wingate did not play with other children, which may account for his antisocial behavior and odd manners when dealing with subordinates and superiors throughout his military career.

In 1923, Wingate graduated from the Royal Military Academy, where he was trained as an artillery officer. Because of his horsemanship skills, he was then sent to the Military School of Equitation. Although he excelled in riding, his rebellious nature did not make him a favorite with his fellow officers. His combative style of conversation and incessant arguing infuriated many.

Wingate did have help. His uncle, General Sir Reginald Wingate, had been Governor General of Sudan and assisted the young Wingate in his career. His Uncle Rex’s duty in the Sudan intrigued him, and soon he mastered the Arabic language. He was granted a leave of absence from the British Army and served with the Sudan Defence Force. He served in the East Arab Corps and patrolled with the SDF in an attempt to snag slave traders and ivory poachers. It was here that the young officer learned to set up ambushes, endure the harsh climates, and go behind the lines to seek out and kill the enemy, traits he would bring with him to Burma.

During his time in the Sudan, Wingate also experienced his first bouts with severe depression. He met Lorna Patterson on his voyage home in 1933 and immediately fell in love with her. He broke off his five-year engagement to Enid Margaret Jelley to marry Patterson in 1935. Jelley was heartbroken and carried a torch for Wingate the rest of her life, never marrying.

In 1936, Wingate was ordered to Palestine. Here he was transformed into a staunch Zionist and saw the importance of creating a Jewish state in the Middle East. When Arab guerrillas began attacking Jewish settlements, Wingate was granted permission to create the Special Night Squads. Once again, Wingate was happiest when in the field with his men. Unfortunately, his outspoken criticism for not creating a Jewish state did not bode well with his superior officers, who relieved him of command.

With the outbreak of World War II, Wingate found himself in command of guerrilla-type units in Ethiopia. He created the Gideon Force, which harassed the Italian supply lines. With less than 2,000 men, he defeated a 20,000-man army and helped put Ethiopian leader Haile Selassie back on the throne.

After contracting malaria, Wingate was given heavy doses of atabrine, which can produce severe depression, and he attempted suicide. After his recovery, he was dispatched to the Far East where he was once again reunited with General Archibald Wavell, who liked the unconventional commander. Soon, Wingate was doing what he did best—leading a guerrrilla force, the famed Chindits, against the Japanese.

Wingate saw the importance of radio communications and air power to destroy enemy positions. He proved that through the proper leadership and training the Japanese soldier, viewed by many as invincible, could be beaten at his own game. His prior service in the Sudan and Palestine had certainly reaped benefits.

Unfortunately, there was a dark side to Wingate. His ability to make enemies by his constant arguing with superior officers, eating raw onions, holding press conferences in the nude, his violent outbursts at junior officers, and his bouts with depression did not endear him to many.

But, as Royle writes, “For him there could be no middle way and no compromise and throughout his brief life he was always found at the place where the extremes met.”

Axis Sally: The American Voice of Nazi Germany by Richard Lucas, Casemate, Havertown, PA, 2010, 322 pp., notes, index, photos, $29.95, hardcover.

Axis Sally: The American Voice of Nazi Germany by Richard Lucas, Casemate, Havertown, PA, 2010, 322 pp., notes, index, photos, $29.95, hardcover.

There is no doubt that propaganda plays a pivotal role in wartime. Leaflets, rumors, and false intelligence reports have influenced the outcomes of numerous conflicts. However, with the advent of film and radio, propagandists discovered a whole new world in which to disseminate information, accurate or not, preying on the psyches of enemy soldiers.

During World War II, two infamous names emerged. “Tokyo Rose,” who spoke to U.S. troops in the Pacific, and “Axis Sally,” who did the same in the European Theater. Sally, however, was no German national. In reality, she was American-born Mildred Gillars, an out-of-work actress who was swept up in the Nazi movement in Germany prior to the U.S. entry into the war.

Gillars’s broadcasts were full of anti-American, anti-British, and anti-Semitic remarks. Her upbringing may be the reason she despised the English. Her Irish Nationalist father disliked the British rule and there is no doubt she adopted his views.

After her parents’ divorce, Gillars did not see her natural father again. She became an actress but did not achieve the stardom she eagerly sought. Once she went to a newspaper posing as a pregnant woman who was searching for her lover. The ruse was concocted by producers of a silent film she and her “lover” were starring in. When it was discovered that it was all false, she and her male co-star were arrested and brought to court. Fortunately, she was released.

During the early 1930s, Gillars went to Berlin with her mother. She taught English to support herself. After Hitler’s rise to power, Gillars’s mother left Germany, but she remained and her career in radio soon began. At war’s end, Gillars attempted to flee the country as a refugee but was caught and repatriated to the United States. She stood trial and was found guilty of treason. She served 12 years in prison and another 30 on parole. She died in 1988 asking, “Am I a citizen again?”

Whether she was naive or just an attention-starved actress, Mildred Gillars will always be remembered as the infamous “Axis Sally.” She began to believe the Nazi propaganda she was spewing over the radio and, as the author states, “paid a heavy price for that delusion.”

Guests of the Emperor: The Secret History of Japan’s Mukden POW Camp by Linda Goetz Holmes, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2010, 148 pp., index, notes, photos, $29.95, hardcover.

Guests of the Emperor: The Secret History of Japan’s Mukden POW Camp by Linda Goetz Holmes, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2010, 148 pp., index, notes, photos, $29.95, hardcover.

It is common knowledge that being held as a prisoner of war by the Japanese during World War II was, by most accounts, a horrific ordeal. There have been numerous books that have described the Spartan conditions that these POWs had to endure. The inmates at Mukden in Manchuria were not only subjected to long hours of forced labor at Mitsubishi’s huge factory complex located nearby. The author has uncovered undeniable proof that as many as 300 POWs became guinea pigs in medical experiments.

This evidence was discovered by Shoji Kondo, a Japanese television producer who was doing extensive research on the camp for a documentary. Kondo found an order issued in 1943 by General Yoshijiro Umezu to send physicians, medical orderlies, and other key personnel to Mukden. These contingents were from Ping Fan, home of the infamous Unit 731, created under the pretext of caring for the prisoners. In reality, the medical teams were exposing the men to various contagious diseases by injection or inhalation, and watching their progress. Many knew that an invasion of Japan was imminent. If the invading troops could be exposed to these ailments, it could cause numerous casualties among the invaders.

Holmes’s book reveals the horrendous living conditions, meager diet, and brutal torture that the POWs at Mukden were forced to bear. She interviewed survivors of the infamous death camp and scoured official documents to tell their unbelievable story.

Every Day a Nightmare: American Pursuit Pilots in the Defense of Java, 1941-1942 by William H. Bartsch, Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 2010, 506 pp., notes, index, photos, $40.00, hardcover.

Every Day a Nightmare: American Pursuit Pilots in the Defense of Java, 1941-1942 by William H. Bartsch, Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 2010, 506 pp., notes, index, photos, $40.00, hardcover.

At the outset of World War II, events in the Pacific Theater looked bleak. The Japanese were succeeding in completing their Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. One such country high on their list for invasion was Java—a Dutch territory—rich with oil that Japan so desperately needed to fuel its war machine.

After the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor, a pair of transports and a freighter set sail from San Francisco en route to the Philippines to reinforce General Douglas MacArthur’s troops defending that country. Instead, the convoy was diverted from its original destination and dispatched to Australia. Aboard the vessels were 73 Curtiss P-40 Warhawks, single-engine fighter planes, destined to assist the Dutch in the Battle of Java.

Although there was a small core of experienced pilots, 14 of the designated fliers had very little flying in the P-40. Of the 101 pilots, only 43 arrived safely on Java to take the fight to the Japanese in the air. With the Allied loss at the Battle of the Java Sea, the country was doomed and plans were made to evacuate the men and planes from the island.

Bartsch spent 16 years researching his account of the 17th Pursuit Squadron (Provisional). He was able to track down many of the unit’s members or their families and gained access to many of the diaries and journals they kept during the war. Very little had been written about these airmen who entered the conflict at such an early date in an attempt to stem the Japanese tide.

The author was indeed fortunate to make the acquaintance of Pulitzer Prize-winning war correspondent George Weller, who spent the entire month of February 1942 in Java. Writing for the Chicago Daily News, Weller described the valiant but hopeless efforts of these brave Americans. Sadly, Weller passed away before the book was published. He had said, “Someone must speak for them.” Bartsch certainly has.

Hitler’s Master of the Dark Arts: Heinrich Himmler and the Black Knights of the SS by Bill Yenne, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2010, 320 pp., bibliography, index, $33.00, hardcover.

Hitler’s Master of the Dark Arts: Heinrich Himmler and the Black Knights of the SS by Bill Yenne, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2010, 320 pp., bibliography, index, $33.00, hardcover.

Heinrich Himmler, the leader of the dreaded SS, grew up fantasizing about a world of knights, warriors, and nobility that had stretched back for centuries in Germany. Although embarrassed about his slight stature and poor eyesight, the meek little son of a schoolteacher would eventually become involved with Nazism, fall under the hypnotic spell of Adolf Hitler, and develop into a shadowy, evil figure within the Nazi leadership.

Himmler founded his infamous group with a mere 200 members. However, by the mid-1930s there were more than 50,000 within its ranks. He was obsessed with producing a master race and sent parties around the world to unearth ancient religious artifacts that, he believed, rightfully belonged to Germany. As the “top cop” of the Third Reich, he envisioned a world ruled by the SS, his personal band of Black Knights.

Himmler engaged in bizarre scientific pursuits and ascribed to strange theories regarding the Earth, its atmosphere and even the possibility of subterranean-dwelling humans.

The evil head of the Gestapo and SS unceremoniously met his end on May 23, 1945, by biting down on a cyanide capsule he had hidden in his mouth in a British interrogation room. The maniacal Nazi leader’s dreams of world conquest, Black Knights, and Aryan superiority, were gone forever.

The Envoy: The Epic Rescue of the Last Jews of Europe in the Desperate Closing Months of World War II by Alex Kershaw, Da Capo Press, Cambridge, MA, 2010, 294 pp., notes, index, photos, $26.00, hardcover.

The Envoy: The Epic Rescue of the Last Jews of Europe in the Desperate Closing Months of World War II by Alex Kershaw, Da Capo Press, Cambridge, MA, 2010, 294 pp., notes, index, photos, $26.00, hardcover.

To many Jews during World War II, Swedish statesman Raoul Wallenberg is an angel. On numerous occasions, the 32-year-old diplomat risked his own life to rescue thousands of Jewish refugees from the clutches of the SS and Lt. Col. Adolf Eichmann, who assisted in devising and later sending thousands of them to the Nazi death camps. Noted author Alex Kershaw has penned a fascinating book focusing on the heroic exploits of Wallenberg and the escape and eventual capture of Eichmann years later when he was hiding in South America.

From July to December 1944, Wallenberg traveled to Budapest, Hungary, and provided passports and safe houses for Jews to help them escape the Nazis. He continually ignored the threats of the SS and the Arrow Cross Party, pro-Nazi Hungarians, and handed out passports to Jews, even while they were boarding trains to Auschwitz, and procured their freedom. Sadly, when the Soviets entered Budapest at the end of the war, Wallenberg was taken into custody and, despite repeated efforts to discover his whereabouts, he was never heard from again.

Kershaw has found survivors who knew Wallenberg and interviewed them at length for his book. As one told him, “He is with me all the time.”

Short Bursts

My New Guinea Diary by Staff Sergeant Ernest C. Ford, White Stag Press, Roseville, CA, 2010, 364 pp., photos, $17.95, softcover.

My New Guinea Diary by Staff Sergeant Ernest C. Ford, White Stag Press, Roseville, CA, 2010, 364 pp., photos, $17.95, softcover.

Ernest C. Ford’s life reads like a slice of the American dream. After running away from his home in New Mexico, he enlisted in the Army because he had always wanted to learn to fly.

And fly he did. When World War II broke out, he was assigned to the 6th Troop Carrier Squadron in New Guinea in the fall of 1942. By conflict’s end, it would be the most highly decorated unit in the Army Air Corps. Armed with no technological tools such as maps or radios, the 6th TCS proved invaluable in defeating the enemy.

Ford remained in the military and flew 385 combat missions in World War II and Korea, earning six Distinguished Flying Crosses and the Air Medal. His diary served as the material for this book. Ford died in March 2010. He was indeed an American hero.

Best Little Stories from World War II by C. Brian Kelly with Ingrid Smyer, Cumberland House, Naperville, IL, 2010, 448 pp., photos, $18.99, softcover.

Best Little Stories from World War II by C. Brian Kelly with Ingrid Smyer, Cumberland House, Naperville, IL, 2010, 448 pp., photos, $18.99, softcover.

Literally a million stories have come out of World War II, from the infantryman in the field to the diplomatic scene, to espionage, in every theater of operation. Award-winning journalist C. Brian Kelly and his wife and co-author, Ingrid Smyer, who was also a journalist, have served on several historical commissions in Virginia, where they reside.

The two have collected numerous anecdotes from a multitude of sources and assembled them into another book of their Best Little Stories collection. These vignettes relate powerful tales of heroism, nostalgia, escape from captivity, tragedy, and even accounts of cowardice during the conflict.

One such fascinating story tells of destroyer exercises simulating an attack on the battleship USS Iowa. However, one such destroyer, the William D. Porter, accidentally let loose a live torpedo, which headed straight for the Iowa. After evading the “fish” and watching it discharge harmlessly a half mile away, much radio communication was exchanged between the parties involved because of the very important person on board—President Franklin D. Roosevelt—en route to Tehran, Iran, for his conference with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soviet Premier Josef Stalin in 1943.

Cobbers in WWII: Memoirs from the Greatest Generation edited by James B. Hofrenning, Lutheran University Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2010, 238 pp., photos, $28.00, softcover.

Cobbers in WWII: Memoirs from the Greatest Generation edited by James B. Hofrenning, Lutheran University Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2010, 238 pp., photos, $28.00, softcover.

Of the soldiers, sailors, airmen, Marines, and Coast Guardsmen, who saw duty during World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt said, “This generation has a rendezvous with history.” FDR was certainly correct. These men and women went on to perform various tasks, some involving risk to their lives, to prevent the spread of Japanese and German aggression.

Author James B. Hofrenning, himself a veteran of the conflict, has written a book to honor those individuals who attended Moorhead College in Concordia, Minnesota, also known as the Cobbers. He has collected short stories from 17 individuals dealing with their wartime experiences in Europe and the Pacific.

In the back of the book the names of 32 Cobbers that were killed in the war or served and returned are listed. Today, more than ever, it is so important that those remaining veterans of World War II relate their stories for their families and future generations. This book is a fitting tribute to them all.

Lost at Guadalcanal: The Final Battles of the Astoria and Chicago as Described by Survivors and in Official Reports by John J. Domagalski, McFarland Publishers, 2010, 224 pp., notes, index, photos, $38.00, softcover.

Lost at Guadalcanal: The Final Battles of the Astoria and Chicago as Described by Survivors and in Official Reports by John J. Domagalski, McFarland Publishers, 2010, 224 pp., notes, index, photos, $38.00, softcover.

The majority of the crews who served aboard the U.S. naval armada that sailed to Guadalcanal during the early days of the war had never even heard of the Solomon Islands. However, after becoming involved in the many sea battles in and around the island they would surely never forget them.

This book deals with the fate of two of the ships, the American heavy cruisers Astoria and Chicago, constructed more than 10 years prior to the war. Unfortunately, neither vessel would survive the six months of fighting in the waters off Guadalcanal. The author has combined tales from survivors, official reports, and other historical accounts to tell the story of the last days of each vessel.

Hitler’s Engineers: Fritz Todt and Albert Speer, Master Builders of the Third Reich by Blaine Taylor, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2010, 272 pp., bibliography, notes, $39.95, hardcover.

Hitler’s Engineers: Fritz Todt and Albert Speer, Master Builders of the Third Reich by Blaine Taylor, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2010, 272 pp., bibliography, notes, $39.95, hardcover.

Here is an intriguing account of two of Nazi Germany’s top architects—Fritz Todt and Albert Speer—who designed many of the buildings and roadways in the country during the reign of Adolf Hitler. Both men’s invaluable contributions to the German war machine prolonged the war by at least a year, according to military historians.

Todt, who was the mastermind behind the Autobahn and the West Wall, commonly referred to as the Siegfried Line, was killed in an unexplained airplane crash, which may have been engineered by his adversaries. Nonetheless, his successor, Albert Speer, continued designing structures such as the Nuremberg Nazi Party Congress buildings. Many of his other works withstood the constant Allied aerial bombardment. Speer also served as Hitler’s Minister of Armaments. He died in 1981 after serving 20 years in Spandau Prison.

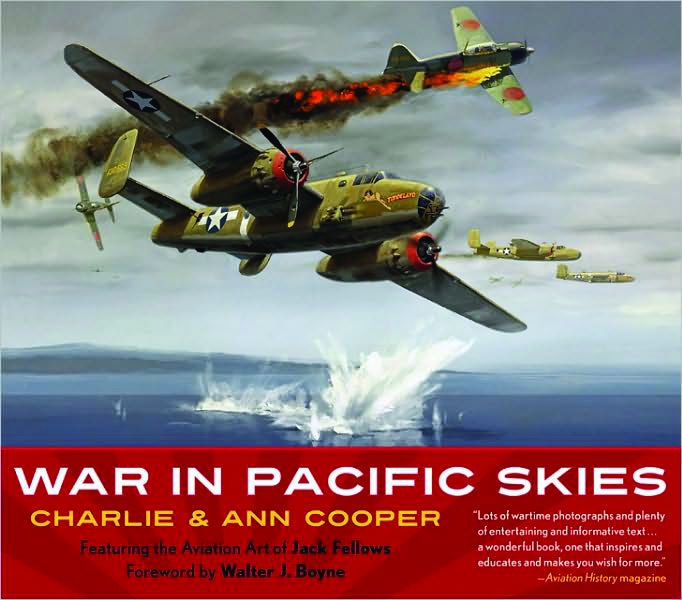

War in Pacific Skies by Charlie and Ann Cooper, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2010, 192 pp., notes, index, photos, $27.99, softcover.

War in Pacific Skies by Charlie and Ann Cooper, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2010, 192 pp., notes, index, photos, $27.99, softcover.

This coffee table book skillfully blends photography and military history to illustrate the war in the Pacific from 1941-1945. Noted aviation artist Jack Fellows has contributed many historical paintings depicting aerial combat that complement the accompanying text of this book. The authors begin by describing the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor and trace the numerous campaigns, culminating in the battle of Okinawa and the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The final two Fellows paintings are particularly poignant. Fellows portrays a U.S. Navy Blue Angels F-18 Hornet fighter bomber flying over the USS Arizona Memorial at Pearl Harbor to honor the memory of the nearly 1,200 men who perished when she sank on that fateful morning of December 7, 1941. The final illustration depicts an F-14 Tomcat fighter of VF-84, or the Jolly Roger squadron, to commemorate the service of Lt. Cmdr. John T. Blackburn of the original Jolly Rogers in World War II, whose groundbreaking air tactics are still in use today. n

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments