By A.B. Feuer

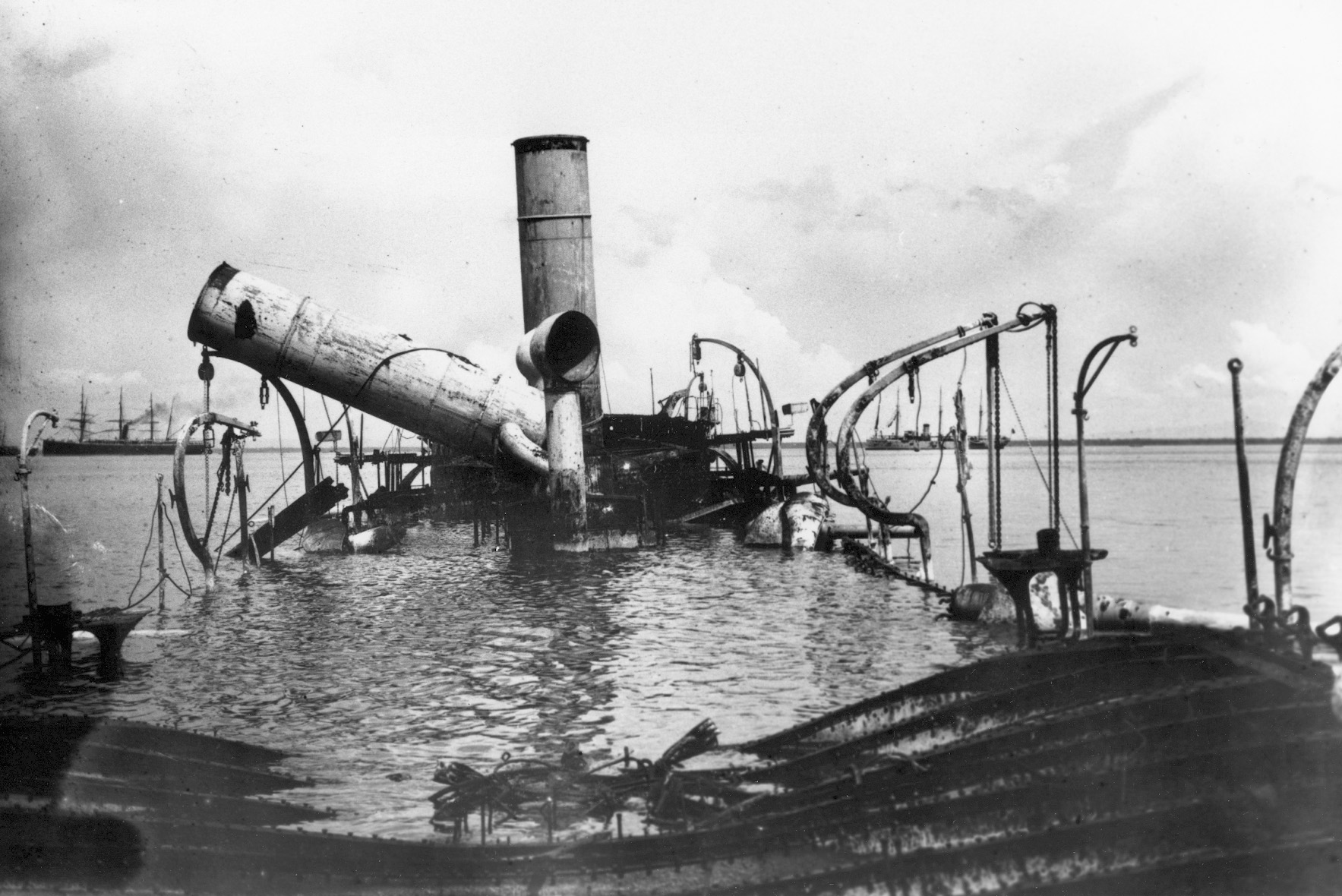

The United States Navy investigation into the February 15, 1898, sinking of the battleship Maine was a difficult undertaking. The nation’s press had been inciting the American people with war hysteria headlines. It was almost impossible for the naval officers conducting the inquiry not to be influenced by public opinion, the enormity of the tragedy, and a thirst for revenge.

There were only two possibilities for the loss of the Maine. Either the ship had been destroyed by an accidental internal explosion or by a deliberate act of sabotage. If it was an accident, then the commanding officer, Captain Charles Sigsbee, was required to explain how it occurred on a ship for which he was responsible. But if the act had been carried out by Spanish authorities, dissident Spaniards, or Cuban insurgents, then Spain was to blame.

The assistant secretary of the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt, was convinced that the fault lay with the Spanish. He was positive that the explosion was no accident, and that the Maine was a victim of “dirty treachery.” Thus, comments supporting the accident theory were a particular worry to Roosevelt; he was a constant advocate of a strong Navy, and Republican congressional leaders had stated that “the [Maine] disaster proved the United States must stop building battleships.”

Teddy Roosevelt countered by saying that this reaction was weak and cowardly. He argued that “battleships were delicate instruments, and even the most advanced naval powers had accidents—they were as inevitable as losses in war. The men who live aboard these ships recognize and accept the hazard. The nation which they defend cannot do less. The loss of the Maine was the price the country must pay to assume its role as a great power.”

Unleashing the Fox in the Chicken House

On the afternoon of February 25, Secretary of the Navy John Long departed his office early, thereby leaving Roosevelt “in charge”—the fox was loose in the chicken house. The assistant secretary began to issue fleet orders as fast as the telegrapher could handle them. A general alert was sent to all ships, stations, and fleet commanders throughout the world ordering them to have their ships fueled and ready to leave port immediately.

Even before the Maine disaster, Commodore George Dewey had sailed with his flagship, the cruiser Olympia, from Nagasaki, Japan, to Hong Kong, closer to the Spanish-held Philippines. But the rest of Dewey’s squadron was still at Nagasaki.

Roosevelt changed that in a hurry. He telegraphed Dewey: “Order your squadron, except the Monocacy, to join you at Hong Kong. In event of declaration of war against Spain, your duty will be to see that Spanish ships do not leave the Asiatic coast, and then begin offensive operations in the Philippine Islands.” When Secretary Long returned to his office, he was surprised and upset at the actions Roosevelt had taken. But the orders to Commodore Dewey were not rescinded.

On Friday, March 25, the final report on the cause of the Maine disaster was delivered to the White House. The following Monday, President McKinley announced to the world that the Maine had been destroyed by a mine. This was the news that the American public had been waiting to hear. The nation’s press called for war, and the cry, “Remember the Maine” quickly healed the festering wounds of the recent Civil War.

The American people became united in a common cause. Only “war” could satisfy their hunger for revenge—the flames of which were fanned by the rival newspapers of Hearst and Pulitzer. Brewing in the wind was a newspaper circulation war in the States, and a shooting war on the high seas.

The loss of the Maine was not the only issue provoking a nationalistic spirit in the United States. The issue of Spanish misrule in Cuba had acquired an importance equal to that of who was to blame for the destruction of the battleship.

President McKinley’s Secretary of State, William R. Day, declared that Spain must accept responsibility for the loss of the Maine. This was not all; Spain should make reparations to the United States, and also grant Cuba her independence. The president, on the other hand, strove for neutrality and sought concessions from Spain in order to satisfy America’s lust for war. But “flag-waving” Congressmen demanded retribution, and continually exerted pressure on McKinley to act militarily against the Spanish.

Declaring War with Spain

Secretary of War Russell A. Alger told the president that Congress was hell-bent for revenge and would declare war in spite of McKinley’s pleas for calmness and cool heads. The war hawks finally prevailed. On April 19, Congress passed a resolution demanding that Spain relinquish her authority and government in Cuba—and McKinley was authorized to use the armed forces to effectuate the decree. Except for a formal declaration, the United States was at war with Spain.

Within a few days, President McKinley ordered a naval blockade of Cuban ports, and a call went out for 125,000 Army volunteers. Then, on April 25, Congress passed a joint resolution that a state of war existed between the two countries.

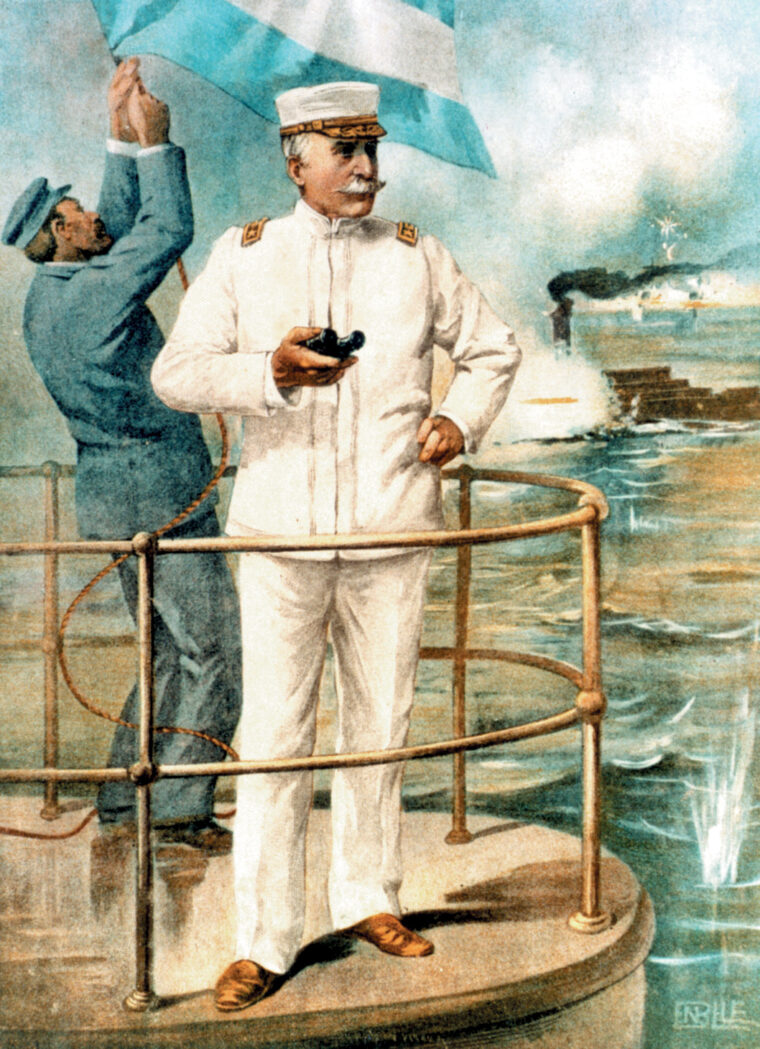

George Dewey had entered the U.S. Naval Academy in 1854, aged 17. He was just beginning his Navy career at the time of the Civil War, and participated in the capture of New Orleans—serving as a lieutenant aboard the USS Mississippi. When Commodore Dewey was assigned to the Asiatic Squadron in January 1898, he was already 60 years old and looking forward to retirement.

On Friday, April 22, Dewey’s fleet was riding at anchor in the British port of Hong Kong. Navy Secretary Long cabled the commodore that the United States had begun a blockade of Cuban ports, but that war had not yet been officially announced. Later that afternoon, the cruiser Baltimore (dispatched by Roosevelt) arrived from Honolulu loaded with powder and ammunition for Dewey’s flotilla. On April 24, because of British neutrality regulations, the American Asiatic Squadron was ordered to leave Hong Kong. While Dewey’s ships steamed out from the British port, military bands on English vessels played the “Star Spangled Banner,” their crews cheering the American sailors.

Commodore Dewey anchored his fleet about 30 miles down the Chinese coast at Mirs Bay and awaited further instructions. During the weeks that Dewey was in Hong Kong, his days were spent in consultation with the various ship captains under his command. All possibilities and eventualities of conflict with the enemy were discussed. He called upon his men to express their opinions freely, and all ideas were given careful consideration. Also while the American squadron was anchored at Hong Kong, Spanish agents played a cat-and-mouse game with Dewey. The Spaniards continually spread rumors concerning the mining of channels surrounding the island of Corregidor and portions of Manila.

America’s Uncomfortable Analysis

Because of all the misinformation he was receiving, Dewey had established his own spy network. He had assigned his aide, Ensign F.B. Upham, to pose as a civilian interested in the sea and ships. Upham would interview crews attached to vessels arriving from Manila. Additional important data was obtained from an American businessman living in Hong Kong who made frequent trips to the Philippines and reported his observations to the commodore. Surprisingly, actual U.S. Naval intelligence was so lacking that Dewey was forced to buy charts of the Philippine Islands at a Hong Kong store.

After as many facts as they could gather were in and sorted out, the final picture they pieced together was not comforting. Approximately 20 Spanish naval vessels were in the Manila area, though most of these were gunboats and small torpedo craft. The largest ships were two cruisers, the Reina Cristina and Castilla.

Actually, it was the Spanish coastal defenses that worried Dewey the most. The island of Corregidor divided the entrance of Manila Bay into two channels. The north passage, between Corregidor and the Bataan peninsula was called Boca Chica and was only two miles wide. The southern channel, Boca Grande, was five miles wide. Strong fortifications mounting high- power German-made Krupp guns had been constructed on the island and mainland. Both channels had been mined by the Spanish. The narrow passage was the shallower of the two, and potentially more dangerous. Dewey was of the opinion that mining the deep channel at Boca Grande would be a much more difficult undertaking, and he doubted the Spanish could have accomplished the feat successfully. Other information relayed to the American fleet reported heavily armed fortresses at Cavite and Manila itself.

Another disturbing problem confronting Dewey was the knowledge that no reinforcements, nor assistance of any kind, had been dispatched by Navy Secretary Long to support the Asiatic Squadron. There was also the realization that in case the battle was not decisive and his fleet was forced to retire from the action, there was no place to go if any of his ships needed repair. Neutrality laws worked against the Americans in all Asian ports—and the United States was 8,000 miles away. Thus, by steaming to Manila, Dewey was burning all his bridges behind him. He had to be victorious. If the mission failed, the likely result was hopeless retreat and eventual annihilation of his squadron.

“You Must Capture Vessels or Destroy”

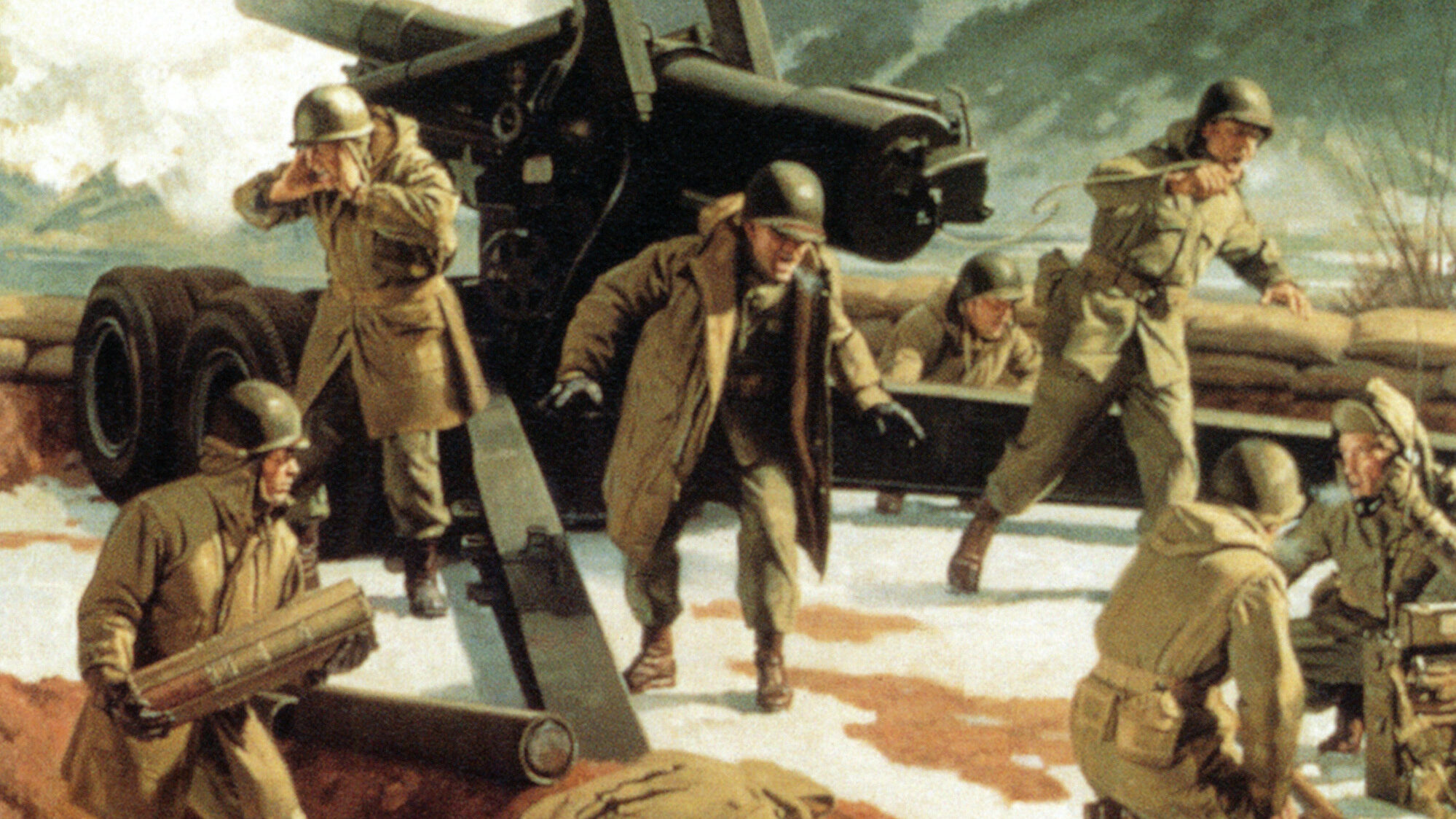

While battle plans were being formulated, crew members of the American flotilla were not taking life easy. The sailors trained continually in target practice, fire drills, and all possible conditions of actual combat. On Tuesday, April 26, Dewey was notified that war had begun and received his sailing orders: “War has commenced between the United States and Spain. Proceed at once to the Philippine Islands, and initiate operations against the Spanish fleet. You must capture vessels or destroy. Use utmost endeavors.”

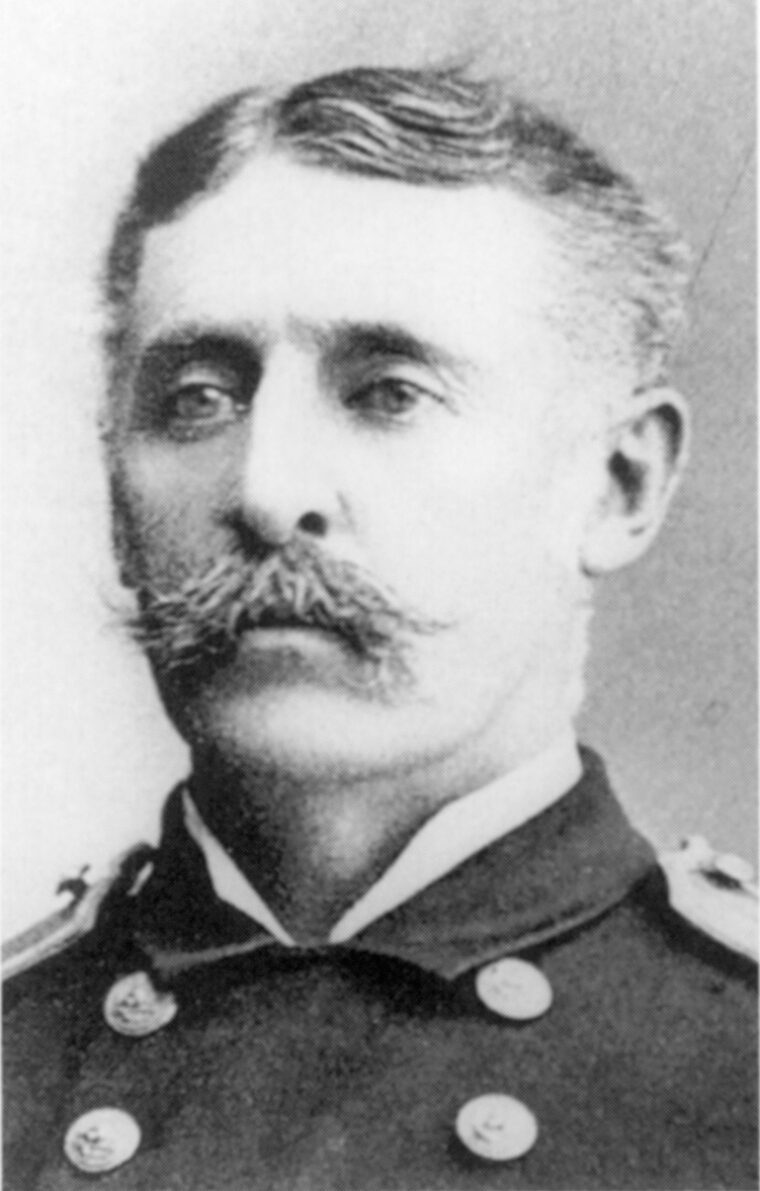

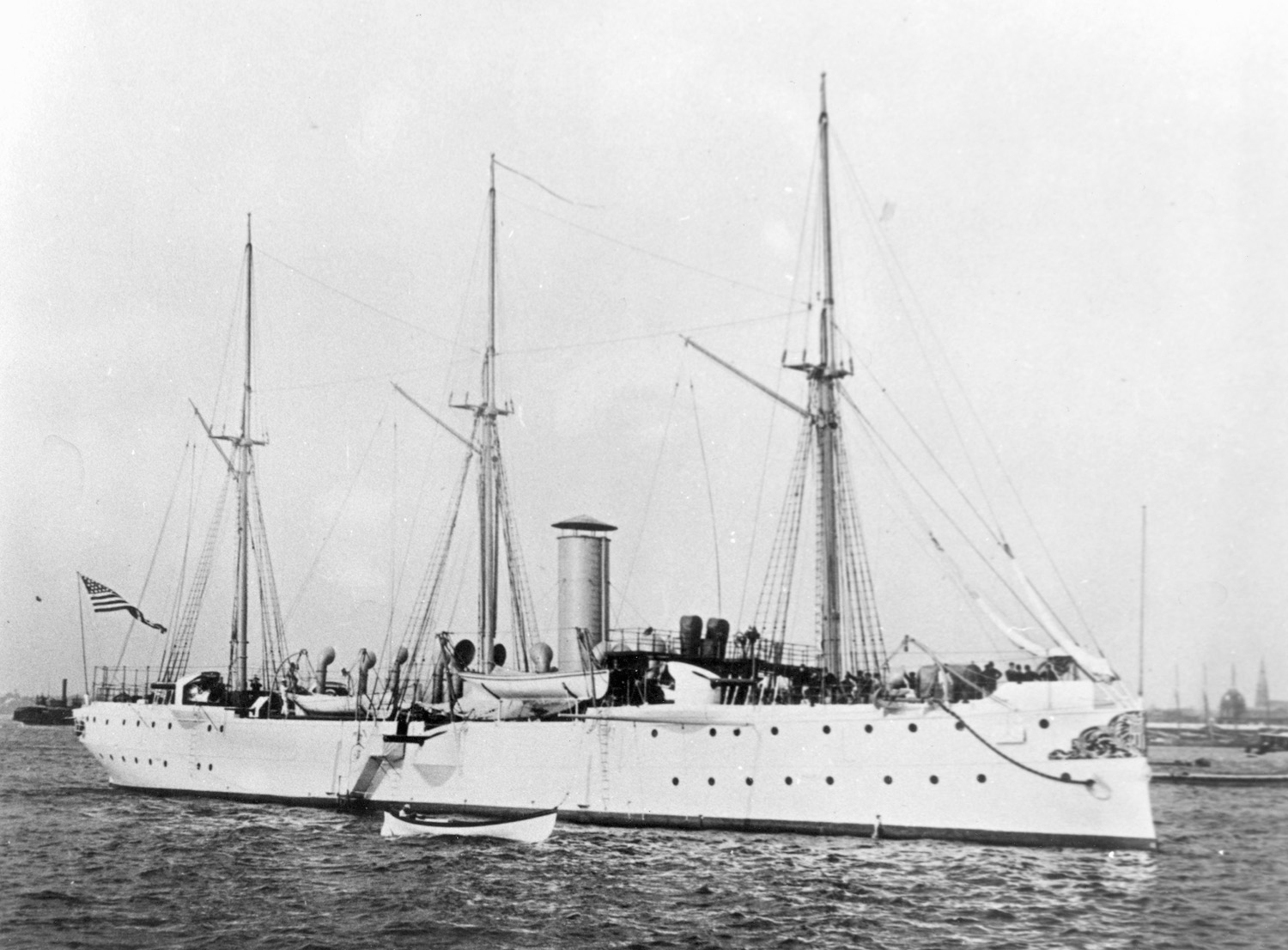

A reporter for the New York Journal, John Barrett, witnessed the American ships leaving the Chinese coast. He wrote: “When Dewey’s squad- ron sailed out from Mirs Bay, it reminded me of thoroughbred race horses, trained to the minute by an expert, who not only knew his animals, but also his competition, and the conditions of the race.” Nevertheless the United States Asiatic Fleet did not include a single battleship. The flotilla was composed of four cruisers, the Olympia, Baltimore, Boston, , and Raleigh; two gunboats, the Concord and Petrel; and the revenue cutter McCulloch. Dewey’s flagship, the Olympia, was commanded by Captain Charles V. Gridley.

The armament of the American vessels ranged from 8-inch to 5-inch guns, plus many smaller caliber weapons. The combined tonnage of the cruisers was only slightly more than that of the battleship Iowa.

Before leaving Hong Kong, Dewey had asked for and received permission to purchase two British cargo ships—the Nanshan and the Zafiro. The merchantmen were loaded with 10,000 tons of coal for the task force and manned by English crews. Three newspaper correspondents sailed with the American fleet. Aboard the McCulloch were Edwin Harden of the New York World and John McCutch- eon of the Chicago Record. Joseph Stickney of the New York Herald had a ringside seat on the bridge of the Olympia,.

Hong Kong was 600 miles from Manila, and there was plenty of time for the men in Dewey’s squadron to worry and wonder what was in store for them. Moreover, they could be anxious about an ambush; more than a thousand islands were scattered throughout the Philippine archipelago, and Spanish warships could be hiding anywhere

During the voyage, individual ship captains kept their men razor-sharp, with constant gun drills and signal exercises. General quarters was called at any hour of the day or night. On Friday evening, April 29, the fleet was ordered darkened, except for small stern lights that were barely visible. On Saturday morning, the island of Luzon was sighted. Fires were kindled under each boiler, and black smoke poured from every stack. The vessels were a bedlam of activity. Splinter nettings were spread and hoses run between decks—ready to instantly drown any fires caused by bursting shells. Ammunition hoists were checked, magazines opened, and every strip of bunting except the signal flags was packed away. Wooden stanchions, rails, and other movable items were stowed below to prevent shrapnel fragments from slashing the men topside in case of an enemy hit.

The Spanish Fleet Possessed a Distinct Numerical Advantage

Wooden lifeboats were lowered and towed behind the McCulloch. All spars and ladders that could not be stowed below decks were swung over the sides of the ships. Unnecessary rigging was taken down, and wire stays attached to the masts were firmly lashed with ropes, so that if shot away, the masts would not crash to the deck and interfere with the operation of the guns. The captain of every ship in Dewey’s squadron informed his crew that the Spanish fleet was larger than the American squadron, and that considering the mined channels and forts that had to be traversed, the enemy had a distinct advantage.

Before he sailed from Mirs Bay, Dewey learned that Spanish Admiral Patricio Montojo had ordered his warships to Subic Bay, about 30 miles north of Corregidor, and was prepared to battle the Americans from an excellent defensive position. The vessels under Montojo’s command were the cruisers Reina Cristina and Castilla and the gunboats Isla de Cuba, Isla de Luzon, Don Juan de Austria, and the Don Antonio de Ulloa. Several smaller ships included four torpedo boats.

Subic Bay was an ideal defensive setup. The entrance was about two miles wide, and halfway up the bay was Grande Island, commanding both sides of the passage. But unknown to Dewey, when Admiral Montojo’s fleet reached Subic Bay, he discovered that only five mines had been placed and that four cannon, supposedly mounted on the island, were instead lying on the beach. Visibly upset, Montojo turned his fleet around and headed for Manila. The Spanish admiral anchored his warships on both sides of the Cavite fortress, where the vessels could be protected by large land-based guns. Montojo was familiar with the harbor area, and was aware that the Americans would be compelled to maneuver in strange waters—and with inaccurate Spanish charts.

Dewey halted his squadron outside Subic Bay and sent the Boston, Baltimore, and Concord ahead as pickets to scout the inlet. The vessels returned in the afternoon and reported they found only a few small sloops and schooners. Dewey also received news that Montojo had left Subic Bay earlier that morning.

All ship captains were immediately summoned to the Olympia, for a conference. Dewey told the officers he intended to enter Manila Bay that evening—regardless of the mines and forts. The Commodore felt confident the Spaniards would not expect such a move, and that they could be taken by surprise. Then the American squadron sneaked along the Philippine coast at four knots so as not to reach the Manila Bay entrance before nightfall.

Battle Stations!

The ships’ crews went to their battle-eve supper at 7 o’clock, and about two hours later, battle ports were closed. A spirit of tense excitement permeated the hot, muggy night. The only light visible was a tiny stern signal, enclosed in a box so it could only be seen by ships directly in the wake of the slow-moving vessels.

The Olympia, led the column, followed by the Baltimore, Boston, Raleigh, Concord, and Petrel. The McCulloch and the coal ships were stationed a mile astern. The sky was overcast but the moon occasionally peeked between the clouds, silhouetting the invading fleet. Off to port, the coast of Bataan could be seen in the distance. Dewey realized that the enemy could be watching their approach and preparing their fortress guns for a heavy barrage. At 10 o’clock, the men were sent to their battle stations—not by the usual bugle call, but by word of mouth. Dewey timed his arrival with precision. It was almost midnight when the Corregidor Island foglight flashed ahead. The American squadron passed into the Boca Grande channel and approached Corregidor abeam to port. Every binocular and gun was trained on the fortress as Dewey’s fleet turned north into Manila Bay.

Suddenly the McCulloch’s smokestack belched a bright flash of flame. Soot from the soft coal she was burning had ignited inside the stack owing to the intense heat of her furnace. The fire glowed for a few minutes, leaving the cutter a perfect target for the enemy’s big guns. But the Spaniards had evidently been taken by surprise. Their weapons were not fully manned, and it took time to ready the batteries for action.

It was not until Dewey’s fleet cleared Corregidor that the Spanish opened fire. The flash from a cannon erupted on the mainland, and a shell ripped across the water, splashing in front of the Olympia,. The Raleigh answered the challenge, followed by 8-inch salvos from the Boston. Direct hits were scored on the enemy’s position, silencing their guns.

Even though the American squadron had been discovered, Spaniards in the forts at the bay’s entrance could not directly tell their comrades farther up the bay what was happening; there was no telegraphic communication between them and the city of Manila. Dewey was only 20 miles from Manila, but decided not to arrive until daylight. He signaled his ships to proceed in double column at a speed of four knots. He also ordered the McCulloch to lead the cargo vessels up to a position where they would be protected by the cruisers and less exposed to a sudden attack. All gun crews were directed to try to get some sleep. The men lay down on the decks near their battle stations. Each ship was in a state of readiness. Every gun was loaded, and ammunition hoists were filled with shells. Officers on watch continually moved about, inspecting every station over and over again. Conversations were conducted in whispers so as not to disturb the sleeping men.

At 5 o’clock Sunday morning, May 1, the dim outline of Manila loomed through the haze on the horizon. A few minutes later, the city’s waterfront could be seen. In a moment, a lookout aboard the Olympia, sighted the outline of ships about five miles south. Lieutenant C.G. Calkins, using his binoculars, brought Sangley Point and Cavite into sharp focus. He could see a line of gray and white vessels stretching eastward from the point, the flame-colored flags of Spain hanging listlessly from their masts. Dewey’s squadron, with bright-hued signal flags whipping in the air, looked every bit like ships on parade as they headed for their date with destiny.

Battle Commences

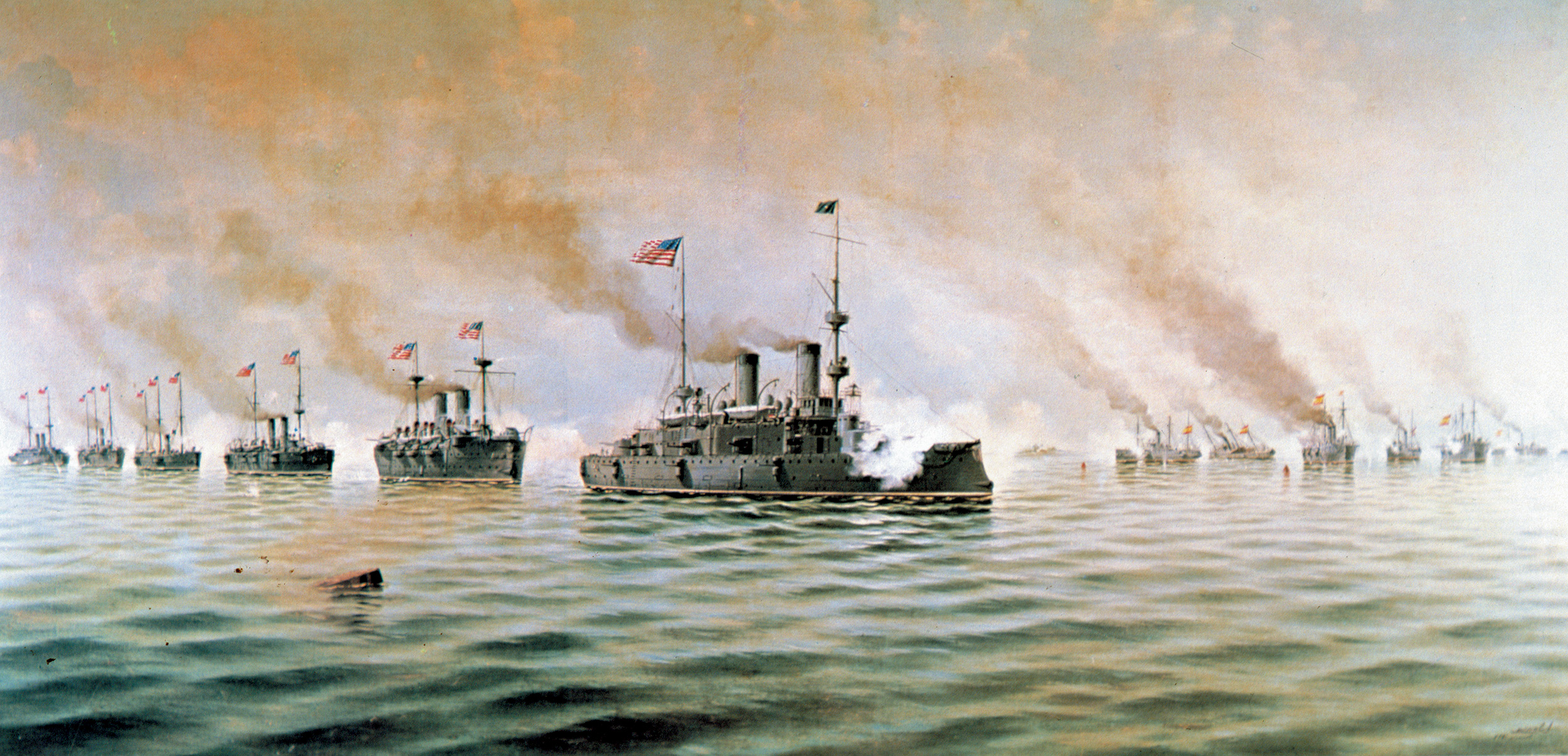

John McCutcheon described the opening of the battle: “At ten minutes after five, the American fleet was off Cavite, and the brightness of the day revealed the enemy’s position. Spanish began firing immediately at a range of four miles. At the sound of the first shot, the Olympia, swung to starboard, and headed straight for the Spaniards. The flagship was followed by the Baltimore, Raleigh, Petrel, Concord, and Boston.”

Aboard the advancing American vessels, gunners, stripped of all clothing except their trousers, waited impatiently for the order to commence firing. Dewey had given strict instructions for his ships to hold their fire until an effective range had been reached—he could not afford to waste powder and shells. The McCulloch and coal ships remained back in the bay, their crews lining the decks to watch the spectacle. Commodore Dewey and Lieutenant Calkins stood on the forward bridge of the Olympia, while Captain Gridley’s post was in the conning tower.

With Dewey’s flagship in the lead, the silent fleet steamed steadily forward. Enemy shells kicked up the water around the squadron, but each vessel maneuvered directly behind the Olympia, with absolute precision and in perfect order.

As the American flotilla drew closer to Cavite, shells from the Spanish fort and anchored warships churned the bay into a frothy foam. Suddenly two large geysers of water shot into the air as the Spaniards exploded a couple of mines in front of Dewey’s advancing column. But the American ships stayed on course, closing the distance between themselves and the smoking Spanish cannon. When each range was called, the gunners aboard the Olympia, lowered their sight-bars.

The flagship continued for another mile, with shots splashing on all sides. The tension among the crew was almost unbearable. As soon as the Olympia, was three miles from Cavite, Dewey ordered the cruiser’s port 5-inch battery turned toward the enemy. Seconds later, a shell burst above the flagship. A boatswain’s mate at one of the aft guns shouted “Remember the Maine!” and every man on deck echoed the cry.

“You may fire when ready, Gridley!”

Dewey checked with his gunnery officer. The range was perfect. The commodore then glanced at his watch. It was exactly 5:40. He looked up at the conning tower and called out, “You may fire when ready, Gridley!”

Dewey had barely finished giving the order when the Olympia, sent a broadside of shells crashing into Fort Cavite. The signal for attack brought every squadron gun into action. A hailstorm of steel from rapid-fire weapons pounded the Spanish fleet, while large-caliber shells concentrated on the fortress. The enemy’s return fire increased. Splashing projectiles hurled a deluge of water across the Olympia,’s deck, thoroughly dowsing the gun crews. Clouds of dense smoke enveloped the Spanish and American vessels. The terrific onslaught by Dewey’s fleet continued as it steamed past the enemy fortifications.

When the port batteries of the American ships would no longer bear on the Spaniards, Dewey’s column swung about and cut loose with their starboard guns. One sailor remarked, “It was a tremendous, roaring procession—a scene of awful magnificence!” Two enemy shells ripped the Baltimore. One missile passed clear through the cruiser without exploding. The other tore across the main deck, wrecking a 6-inch gun and wounding eight men.

The Boston was also blasted. A projectile struck her port quarter. A fire broke out, but it was quickly extinguished. Time-fuse shells continually exploded above the American fleet, scattering steel fragments in all directions. Joseph Stickney was on the Olympia,’s bridge during the conflict and described the battle: “One projectile headed straight for the forward bridge, but exploded less than a hundred feet away. Shrapnel sliced the rigging over the heads of Commander Lamberton and myself. Another shell, about as large as a flatiron, gouged a hole in the deck a few feet below the Commodore.”

Tons of Spanish shells fell about the American squadron, whose salvation was the poor marksmanship of the enemy. Most of their shots were too high and roared into the bay beyond. After passing the enemy’s line for the second time, the Olympia,’s column swung around again on a closer tack, giving the port guns a second chance at the Spaniards. The Cavite shoreline was a veritable inferno of flames and the pandemonium was indescribable. Suddenly the Americans spotted the Reina Cristina steaming out to meet the Olympia,. Dewey ordered his ships to concentrate their fire on the reckless enemy vessel. Rapid-fire shells riddled the side of the Spaniard, and gunfire swept her decks. An 8-inch projectile struck the enemy cruiser in the stern, plowing completely through the ship and blowing up its forward magazine.

Dewey’s fleet had just finished its fifth circle of the enemy’s position, when Gridley reported that there were only 15 rounds per gun for the Olympia,’s 5-inch battery. Not wishing to alarm the crew, the commodore ordered his squadron to withdraw for “breakfast.” While the battle-weary fleet steamed north, beyond the range of Spanish guns, clearing smoke near Cavite revealed the wreckage of the fort and fires burning on several enemy vessels.

How Morale on the Olympia Plummeted

Once safely out in the bay, Dewey summoned his ship captains to the Olympia,. Remaining ammunition was checked and powder and shells redistributed where necessary. During this unorthodox pause in the action, Stickney wrote the following: “We had been fighting a determined and courageous enemy for almost three hours, without noticeably diminishing their volume of fire. So far as we could see, there was no indication that the Spaniards were less able to defend themselves than they had been at the beginning of the engagement.

“We knew the Spanish had an ample supply of ammunition, so there was no hope of exhausting their fighting power by a battle lasting twice as long. If we should run short of powder and shell, we might possibly become the hunted instead of the hunter. The gloom on the bridge of the Olympia, was thicker than a London fog in November. We had all been disappointed by results of our gunfire. For some reason, the shells seemed to go too high or too low. The same had been the case with the Spaniards. On our final circle, we were within 2,500 yards of the enemy. At that distance, and in a smooth sea, we should have had a large percentage of hits. However, as near as we could judge, we had not crippled the foe to any great extent.”

While his ravenous sailors ate a hearty meal, Commodore Dewey scouted the enemy position with his binoculars. Heavy smoke obscured Cavite, but he still could make out the tall masts and flags of Spanish ships. Occasionally the sound of exploding ammunition could also be heard in the distance. After a three-hour respite, Dewey again formed his battle line for attack. This time the Baltimore was in the lead.

As the American fleet approached Cavite, the sound of church bells in downtown Manila floated peacefully across the bay. Curious spectators could be seen crowding the rooftops of the city. They appeared to be preparing to watch a pageant or play.

Dewey’s squadron and the big guns of Cavite opened fire at the same time. Only one Spanish vessel slipped her moorings and came out fighting. The captain of the Antonio de Ulloa nailed her flag to the mast and engaged the American cruisers in a one-sided firefight. Within a few minutes, the Spanish vessel went down with all hands.

Spotting the White Flag of Surrender

Recognizing the futility of continuing the conflict, Admiral Montojo issued his last order to his fleet officers: “Scuttle and abandon your ships!” The admiral then escaped to Manila in a small boat.

About 12:30, a white flag of surrender was seen flying over Fort Cavite, and Dewey anchored his squadron near Manila.

Three enemy ships had been sunk by Dewey’s squadron. Eight Spanish vessels had been set afire and scuttled by their crews. A total of 381 Spaniards were killed during the fierce battle. While aboard the American fleet, only eight men were wounded. Amazingly, not one member of Dewey’s squadron was killed in action.

After the conflict, Commodore Dewey declared: “This battle was won in Hong Kong Harbor. My captains and staff officers working with me, planned out the fight with reference to all contingencies, and we were fully prepared for exactly what happened. Although I recognized the alternatives from reports that reached me—that the Spanish might meet me at Subic Bay, or possibly near Corregidor, I made up my mind that the battle would be fought right here that very morning, at the same hour, and with nearly the same position of opposing ships. That is why and how, at break of day, we formed in perfect line, opened fire, and kept our position without mistake or interruption until the enemy ships were destroyed.”

Dewey’s engagement was unsurpassed in the naval history of that time. Never before had an entire fleet been wiped out without the loss of a ship—or a single man—on the part of an attacking force. Commodore Dewey’s victory at Manila Bay is still one of the most romantic and decisive in world history.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments