By Al Hemingway

It has been said that when Dwight David Eisenhower was president of the United States from 1952-1961, he was not a hands-on chief executive. Because of his inexperience in legislative and judicial matters—Eisenhower had come from a military background—it was his cabinet members who made all the hard decisions. Today, we know this is the farthest thing from the truth. As declassified documents show, Eisenhower was anything but a laid-back president. His energy and leadership, even with medical setbacks during his second term, were evident.

In his new biography, Eisenhower: In War and Peace (Random House, New York, 2012, 950 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $40.00, hardcover), historian Jean Edward Smith lays bare the life of the 34th president of the nation, including his greatest achievements and his failures.

Dwight was born in Texas in 1890. The Eisenhowers relocated to Abilene, Kansas, when he was two years old. “Ike,” as he was called by his family and closest friends, was a good student with a “retentive memory” and a “natural gift for clear writing, effective prose.” He took the test for West Point and passed, graduating in 1915 with the “Class the Stars Fell On.” Out of the 164 newly commissioned second lieutenants in the class, 59 attained the rank of brigadier general or higher, with Eisenhower and Omar Bradley reaching the five-star plateau.

Life in the peacetime Army was difficult. Promotions were slow and plumb assignments were rare. Eisenhower, however, had an edge. Generals like John J. Pershing, Fox Conner, George Moseley, and Walter Krueger took a liking to the young officer and each in his own way guided his career with invaluable advice.

In 1915, Eisenhower met and fell in love with Mary Geneva Dowd, called Mamie, and the two married in 1916. The Dowds were a well-to-do family from Denver, Colorado, and Mamie’s father assisted the newlyweds with a monthly stipend to ease the burden of a second lieutenant’s pay.

In September 1917, Mamie gave birth to a son whom she called “Little Ickey.” Tragically, in 1921, “Ickey” died from scarlet fever that had been passed on to him by a woman hired to do household chores. Unknown to them, she had just recovered from the disease but was still a carrier. Eisenhower was devastated. Each blamed the other and they grew increasingly distant. It would be a breach that would never heal in their nearly 53 years of marriage.

Meanwhile, Ike worked closely with Douglas MacArthur, spending several years with him in the Philippines. At first, they got along well together, but toward the end of his tenure in the Far East, MacArthur’s super ego and ranting were too much for Eisenhower.

It was during his Washington, D.C., assignment working for General George C. Marshall that Eisenhower’s talents as a staff officer and planner really began to shine. Working long hours, Ike devised the strategy of the crossChannel invasion from England to France that would ultimately come to fruition on June 6, 1944.

Although junior to many, Marshall chose Eisenhower to be the supreme commander of the Allied Forces. He matured as a tactical commander and was often the sounding board between the American and British leaders. It was here he got his first taste of politics dealing with President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill. It would serve him well during his eight years as president.

When he retired from the Army, Ike took the job as president of Columbia University, but it was the world of politics that he yearned for. When approached to run on the Republican ticket in 1948, he declined. It was a wise choice; he sensed that President Harry Truman would probably win reelection. As Smith points out, Eisenhower “knew the pulse of the American electorate better than anyone.”

Smith does a superlative job of bringing to light Ike’s achievements during his two terms as president, narrowly averting a world war in the Middle East during the Suez incident, ending the Korean War, and keeping the United States out of the Vietnam debacle in 1954. Despite these successes, it was the St. Lawrence Seaway project, opening traffic to the Great Lakes, and the interstate highway system that he was most proud of during his terms in office.

As president, Eisenhower kept the United States from being involved in war, built a highway system that remains in use today, and began the space program after the Russians launched Sputnik in 1957. That program would eventually land a man on the moon a little over a decade later.

When he left office in 1961, Eisenhower wanted his five-star rank restored. This would require an act of Congress and left incoming President John F. Kennedy baffled. When he asked his military assistant, Brig. Gen. Ted Clifton, why the former president wanted to be known as general instead of Mr. President, Clifton replied that attaining that rank was “something Ike had worked for all his life.”

“Besides,” Clifton said, “if he is a five-star general, he needs no favors from you or the White House.” The bill was passed with no dissenting votes.

Despite rising to the highest office in the land, the man from middle America, who once said that he came from the “ordinary people,” wanted to be remembered as an old soldier who had faithfully done his duty.

Japan’s Last Bid for Victory: The Invasion of India, 1944 by Robert Lyman, The Praetorian Press, South Yorkshire, England, 2011, 297 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $50.00, hardcover.

Japan’s Last Bid for Victory: The Invasion of India, 1944 by Robert Lyman, The Praetorian Press, South Yorkshire, England, 2011, 297 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $50.00, hardcover.

Hailed as the “Stalingrad of the East,” the Battles of Kohima and Imphal were the culmination of Japan’s last-ditch attempt at invading India. Conceived as a spoiling attack to disrupt Allied offensive plans, they were also an effort by the Japanese to seize additional territory for its empire. The Japanese 15th Army, commanded by Lt. Gen. Mutaguchi Renya, laid siege to Kohima in early April 1944. Although lightly defended by the Assam Regiment and Assam Rifles, the mixed British and Indian troops put up a spirited defense. There was hard fighting around the tennis courts and the field supply depot located on Kohima Ridge. Positions were mere yards from each other as the two sides engaged in bloody hand-to-hand combat during the fighting.

“Kohima was a battle that we could see plainly from the sky,” said Flight Sergeant Jim Bell of Royal Air Force No. 31 Squadron. “It was pitiful—like World War One—slit trenches, no-man’s land etc.”

On April 18, soldiers from the 1st Battalion, 1st Punjab Regiment fought their way through to relieve their besieged comrades. Despite horrendous casualties, they had held. Japanese troops were also repulsed and driven back into Burma after an unsuccessful try at defeating British forces there.

Lyman, a retired British Army officer, has written a wonderful narrative describing in rich detail not only the bitter no-quarter combat between the adversaries, but also the terrible weather conditions that impeded both sides during the campaign. Lyman is well qualified to tell the story of the British victories at Kohima and Imphal. His biography of Lt. Gen. William Slim, the Allied 14th Army commander whose strategy paved the way for victory, was the groundwork for this book.

This is a well-written story dealing with a slice of World War II history that is sadly neglected but was nonetheless an important part of the Allied victory in the Southeast Asian Theater of Operations.

General Albert C. Wedemeyer: America’s Unsung Strategist in World War II by John J. McLaughlin, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2012, 336 pp., photographs, bibliography, notes, $32.95, hardcover.

General Albert C. Wedemeyer: America’s Unsung Strategist in World War II by John J. McLaughlin, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2012, 336 pp., photographs, bibliography, notes, $32.95, hardcover.

In the late fall of 1944, a single transport plane circled the airfield at Kunming, China, and landed unceremoniously at the far end of the field. In another area, a large group of American and Chinese officials was anxiously awaiting the arrival of the new commanding general of U.S. forces in China and the China-Burma-India Theater. As the entourage stood there, one tall, slightly built officer stepped from the plane at the other end of the airstrip and commandeered a ride on a truck to introduce himself to the party. “My name’s Wedemeyer,” the man said, shaking hands with everyone. “Glad to be here.”

The unflappable command style of Lt. Gen. Albert Coady Wedemeyer was a far cry from his predecessor, Joseph “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell, who, although a dynamic combat leader, did not have the tact to deal with the Chinese, especially Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, the leader of the Nationalist forces.

Wedemeyer was relieving a man who was immensely popular in the American press but not among the Chinese. The Nebraska native, however, was used to dealing with temperamental political figures, as with the case of Prime Minister Winston Churchill when Wedemeyer, then a lieutenant colonel, had to brief him, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and General George C. Marshall on his paper outlining a cross-Channel invasion of mainland Europe in 1943, a full year before D-Day actually occurred. Churchill never forgave or forgot Wedemeyer’s careful and accurate analysis that opposed his North Africa, Mediterranean, and Balkans approach to defeating Nazi Germany.

McLaughlin has given us a fresh, new account of the life of a man who embodied the West Point motto of “Duty, Honor, Country.” He also disputes others, especially noted historian Barbara Tuchman and her negative assessment of Wedemeyer.

Here is a long overdue book about a true American hero, unpretentious but brutally efficient, clever, and a top-notch strategist who accurately predicted world events.

Albert Coady Wedemeyer deserves no less.

December 1941: 31 Days That Changed America and Saved the World by Craig Shirley, Thomas Nelson, Nashville, TN, 2011, 646 pp., bibliography, notes, $24.99, hardcover.

December 1941: 31 Days That Changed America and Saved the World by Craig Shirley, Thomas Nelson, Nashville, TN, 2011, 646 pp., bibliography, notes, $24.99, hardcover.

Here is a colorful and descriptive account of the days prior to December 7, 1941, when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, and the days immediately following it until December 31. The author has taken the entire month and has literally painted a picture of what life was like for Americans during that period.

Until that time, the wars in Europe and Asia were not in the forefront of the American psyche. The country was beginning to emerge from the depths of the Great Depression that had gripped her for the past decade. Most of the population was steeped in isolationism. Americans remembered all too well the “war to end all wars” just a quarter century before and wanted no part in another land war in Europe, much less Asia.

Sadly, the United States was woefully unprepared for war. President Roosevelt had implemented the Lend Lease Act to assist Great Britain, which was standing alone against the might of Nazi Germany.

Shirley’s book is an excellent snapshot of that one crucial month in 1941 that dramatically altered world events and swept America into the maelstrom of yet another world war—a war that would change the way we think and live forever.

Twelve Desperate Miles: The Epic World War II Voyage of the SS Contessa by Tim Brady, Crown Publishers, New York, 2012, 304 pp., photographs, notes, $26.00, hardcover.

This is a superb account of the Battle for Lyautey in French Morocco in November 1942 and the important role that the SS Contessa played during the fight. The Contessa was an old freighter owned by the Standard Fruit Company that had been used prior to the war for hauling bananas and coconuts from the Caribbean. It was selected because its design allowed it to navigate extremely shallow waters, a task that had to be performed to supply U.S. troops via the Sebou River to the airfield—a distance of 12 miles.

To accomplish this task, Welsh-born William Henry John would remain in command of the ship with a mishmash of a crew that included released inmates from prisons in the area.

Also, a Frenchman, Rene Malevergne, known as “The Shark,” was smuggled out of Morocco to participate in the operation. Malevergne was a river pilot and was intimately familiar with the Sebou River. In the end, he would be the first Frenchman to be awarded the U.S. Navy Cross and the Silver Star Medal for heroism.

Twelve Desperate Miles is a topnotch thriller, full of suspense and intrigue, about the daring exploits of a small vessel’s crew in achieving victory in Morocco during the early days of the North African Campaign.

Five Days That Shocked the World: Eyewitness Accounts from Europe at the End of World War II by Nicholas Best, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 2011, 369 pp., photographs, bibliography, notes, index, $27.99, hardcover.

Five Days That Shocked the World: Eyewitness Accounts from Europe at the End of World War II by Nicholas Best, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 2011, 369 pp., photographs, bibliography, notes, index, $27.99, hardcover.

This story centers on the final days of World War II, from Mussolini’s execution to the Nuremberg trials, told by people who witnessed the historic events. The author has selected well-known leaders and commanders from all sides to explain their actions and motives during the remaining days of the fighting.

Best delivers a detailed and exciting narrative dealing with the deaths of Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler. He is quick to point out that accounts of the Führer’s last days in the bunker in Berlin greatly differ and allows readers to draw their own conclusions.

Other lesser-known personalities, destined for notoriety years after the conflict ended, are Henry Kissinger, John F. Kennedy, Robert Dole and, interestingly enough, Private Josef Ratzinger, a reluctant conscript in the SS. He would finish his time in seminary after the war, becoming a Catholic priest in 1951 and ordained as Pope Benedict XVI in 2005.

This is a captivating book that flawlessly intertwines the stories of the individuals who played a part, large or small, in the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945.

Short Bursts

Shattered Genius: The Decline and Fall of the German General Staff in World War II by David Stone, Casemate Publishers, 2011, 424 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $34.95, hardcover.

Shattered Genius: The Decline and Fall of the German General Staff in World War II by David Stone, Casemate Publishers, 2011, 424 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $34.95, hardcover.

How could a group of professional senior officers fall to the whims of the Nazi Party during their tenure as rulers of Germany? That is a question that author David Stone answers in this fascinating book about the creation and complacency of the German General Staff, a highly motivated group whose strong sense of duty and honor was compromised when they formed, as he refers to it, an “unholy alliance” with Adolf Hitler.

The wily Hitler realized that he could not undermine his regular army senior officers. Behind the scenes he, together with SS chielf Heinrich Himmler, Luftwaffe leader Hermann Göring, and Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels, orchestrated the 1934 Night of the Long Knives, eliminating the leadership of the rival SA and numerous members of Hitler’s political opposition.

Many in Hitler’s staff argued against war, but the sly former paper hanger maneuvered his options like chess pieces to gain the favor of the German people and the junior officers to forge ahead with his plan to conquer Europe. In fact, it was not until July 1944, after the botched plot to assassinate Hitler failed, that he assumed complete control of the general staff.

This is a fascinating account of the inner workings of the German Army during the 1933-1945 period and their continuous struggle to perform their duty in an honorable fashion, only to fall prey to the madness of one man’s dream of world conquest that would ultimately destroy the country.

Hobart’s 79th Armoured Division at War: Invention, Innovation & Inspiration by Richard Doherty, Pen & Sword Books, South Yorkshire, England, 2011, 240 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $39.95, hardcover.

Hobart’s 79th Armoured Division at War: Invention, Innovation & Inspiration by Richard Doherty, Pen & Sword Books, South Yorkshire, England, 2011, 240 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $39.95, hardcover.

Although he never led men in battle, Maj. Gen. Percy Cleghorn Stanley Hobart was a visionary when it came to the subject of armored vehicles. When he joined the tank corps in 1923, he soon realized that the tank was the wave of the future. His innovative thinking was ahead of its time. Because of his ideas, however, he was forced into retirement and became a member of the Home Guards as a lance corporal. When Prime Minister Winston Churchill learned of this, Hobart was immediately reinstated and given command of the 11th Armored Division. Because of health reasons, he was transferred to the 79th Armored Division, a specialized unit of modified tanks that could help Allied soldiers get ashore in the upcoming invasion of France.

Together with the Royal Engineers, Hobart’s tankers were driving a wide variety of unusual vehicles such as the Crocodile, fitted with a flamethrower instead of a gun. Another carried a temporary bridge that could drop a 30-foot span in seconds. The Crab, a tank equipped with rotating chains, was used to clear the beaches of any land mines. Collectively, the innovative armored vehicles were called Hobart’s Funnies.

After the war, Hobart continued his endeavors with the same high level of energy that he had during his time in the Army. He died of cancer in 1957 and, as the author writes, “He left a legacy that would benefit many.”

Riders of the Apocalypse: German Cavalry and Modern Warfare, 1870-1945 by David R. Dorondo, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2012, 336 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $36.95, hardcover.

Riders of the Apocalypse: German Cavalry and Modern Warfare, 1870-1945 by David R. Dorondo, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2012, 336 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $36.95, hardcover.

Despite the armored blitzkrieg into Poland in 1939 that started World War II, the German Army still possessed mounted cavalry in an age of mechanized warfare. In fact, seven million horses were in service in all the European armies at the outset of the conflict, with Germany possessing nearly three million of that number.

For the most part, the author states that the German cavalry units, excluding the dreaded horsemen of the Waffen SS, performed their duties honorably during the war. They were imbued with a strong character and professionalism because of their lineage dating back centuries. Sadly, this noble spirit was wasted upon an evil totalitarian dictatorship that sent their country into ruins.

With the exception of ceremonial units, the mounted horse units are not a part of today’s military in most countries. The day of the glorious charges into the teeth of the enemy’s defenses has long vanished.

“He risked his own life and paid in full,” the author writes, “more frequently than his rider. The horse should be remembered.”

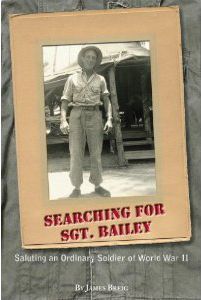

Searching for Sergeant Bailey: Saluting an Ordinary Soldier of World War II by James Breig, Park Chase Press, Baltimore, MD, 2011, 303 pp., photographs, bibliography, $24.95, softcover.

Searching for Sergeant Bailey: Saluting an Ordinary Soldier of World War II by James Breig, Park Chase Press, Baltimore, MD, 2011, 303 pp., photographs, bibliography, $24.95, softcover.

Approximately 16 million men and women served during World War II. The vast majority performed their duties honorably and were discharged to the civilian world to continue in their careers and professions. Not all of these individuals were able to readjust to civilian life in a smooth, orderly fashion. Many were haunted by their combat experiences and were unable to move forward in a positive manner.

Such was the case of James Boisseau Bailey—a native of a small hamlet in Virginia—who had trouble after his return from the Pacific Theater in 1945. Oddly enough, the author, James Breig, discovered the letters that Bailey had written to his mother in an antique shop near Williamsburg, Virginia. The correspondence between the two sparked an interest in Breig, who immediately began an odyssey to find out what kind of person Bailey was and how he lived after the war. It was a sad story complete with alcoholism, drifting from job to job, and the loneliness that accompanies such a life.

Here is a tribute to one ordinary man’s journey that took him halfway around the globe to participate in historical events that helped shape the future of the world—even in a small way. It is also an honor to all the Sergeant Baileys who served during that period of American history and earned the title of the “greatest generation.”

Images of War: Armoured Warfare in the North African Campaign by Anthony Tucker-Jones, Pen & Sword Books, South Yorkshire, England, 2011, 144 pp., photographs, $24.95, softcover.

As the title implies, this book is crammed with numerous photographs, many of them rare, dealing with tank warfare in the North African campaign. As the author correctly points out, the desert terrain of North Africa was quite suitable for armored battles and catapulted General Erwin Rommel into the limelight because of his lightning-fast tactics, earning him the sobriquet “The Desert Fox” and making him a national hero back in Germany.

Tucker-Jones also has uncovered some fascinating pictures of the Italian Tank Corps when it invaded Egypt in 1940. When Benito Mussolini’s tankers were roughly handled by British forces, Hitler dispatched armored units with Rommel in command to bolster the Italian dictator’s forces.

The author covers the desert war from Italy’s invasion to the German intervention and the autumn of 1942 when Rommel’s game of cat and mouse with the Allies came to an end because of his lack of equipment and supplies.

A good book that is especially beneficial for those who are interested in this part of the conflict, its clear, concise format will enable readers to attain a better understanding of the desert campaign and also learn about its leaders and the various tanks employed during the fighting.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments