By Michael E. Haskew

Seventeen months after the juggernaut of Japanese conquest in the Pacific had come to an abrupt end with the Battle of Midway, American strategists were ready to launch their long-awaited offensive in the Central Pacific.

The road to Tokyo lay across thousands of miles through a string of fortified islands––often one or two spits of land among numerous coral shelves that peaked just above the water surrounding an extinct volcano. Known as atolls, these clusters might consist of only a few small islands or several dozen.

When Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief, United States Pacific Fleet, set Operation Galvanic in motion during the summer of 1943, its objective was the conquest of the Gilbert Islands, particularly two atolls, Tarawa and Makin, approximately halfway between Hawaii and Australia.

Control of the Gilberts was essential to the U.S. offensive in the Central Pacific, eliminating the threat of air attack or harassment from the rear as American forces reached farther across the ocean to attack the major Japanese base at Kwajalein atoll in the Marshall Islands, 500 miles northwest of the Gilberts. Operation Galvanic would also provide the U.S. Marine Corps an opportunity to hone its skills in amphibious warfare, the essence of its being, rapid landing, and movement across a contested beach.

Operation Galvanic was set for November 20, 1943, and charged with its execution were the 2nd Marine Division and the 165th Regimental Combat Team of the U.S. Army’s 27th Infantry Division. Vice Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, the victor at Midway, commanded the Central Pacific Force, while three major generals named Smith assumed vital command roles for the coming fight: Marine Holland M. “Howlin’ Mad” Smith commanded the V Amphibious Corps, Julian C. Smith the 2nd Marine Division, and Ralph C. Smith the Army’s 27th Infantry Division.

The combined strength of U.S. ground troops exceeded 35,000, and the force that set sail from several locations in early November included an array of transports protected by 17 aircraft carriers, 12 battleships, eight heavy cruisers, four light cruisers, and 66 destroyers. Altogether more than 200 ships converged on a rendezvous point near the intersection of the International Date Line and the equator. From there, the armada split into three groups. The carrier group maintained vigil against Japanese air or naval attacks, particularly from the direction of Kwajalein, while the northern force headed for Makin and the southern steamed toward Tarawa, 100 miles distant.

Three days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese had seized Tarawa and Makin without opposition. For more than 18 months, they had worked to fortify the principal islets of the atolls, Betio and Butaritari. In August 1942, the Marines’ 2nd Raider Battalion under Colonel Evans F. Carlson conducted a raid against the small garrison at Makin, awakening the Japanese to the vulnerability of island outposts along their defensive perimeter.

By the middle of 1943, the Japanese had established a “Zone of Absolute Defense” that encompassed territory from Burma in the west to the Dutch East Indies through New Guinea and the Marshalls and to the Kuriles in the northeast. Island groups outside this zone, such as the Gilberts, were to be defended to the last man, buying time to bolster inner defenses and to exact the heaviest possible toll on the Americans.

Under the command of Rear Admiral Tomanari Saichiro, 2,600 troops of the 6th Yokosuka Special Naval Landing Force bolstered the garrison on Betio. Along with 1,200 Korean forced laborers and 1,000 Japanese construction workers, they built concrete blockhouses with walls several feet thick, reinforced with steel and coconut logs and covered with tons of sand. Machine-gun nests and pillboxes were sited with interlocking fields of fire, barbed-wire entanglements were strung, and obstacles that could tear into the thin skin of a landing craft were submerged around the islet and in the 17-mile-long, nine-mile wide lagoon that fronted the beaches chosen by American planners for the coming assault. Seven tanks were also buried in sand up to their turrets in positions covering the lagoon.

More than 40 artillery emplacements studded Betio, and the islet fairly bristled with the muzzles of 13mm heavy machine guns to 120mm field pieces. Also present were four heavy 8-inch guns of British manufacture that had been purchased by the Japanese at the height of the Russo-Japanese War in 1905. Contrary to popular belief, they were not captured at Singapore and transported the great distance to the Gilberts.

Approximately two miles from end to end and 800 yards across at its widest point, the islet of Betio consists of only 291 acres, about half the size of New York City’s Central Park. Yard for yard, Betio may well have been the most fortified territory on Earth. In August, Rear Admiral Keiji Shibasaki replaced Saichiro. So impressed was the new commander with the defenses at Betio that he boasted, “A million men cannot take Tarawa in a hundred years!”

General Holland Smith and Admiral Turner chose to accompany Task Force 52, the Makin force, aboard the battleship Pennsylvania, while command of Task Force 53, headed to Tarawa, was given to Rear Admiral Harry W. Hill aboard the battleship Maryland. It had been agreed that the Makin operation should end swiftly and that Holland Smith and Turner could reach Tarawa quickly should any problems arise there.

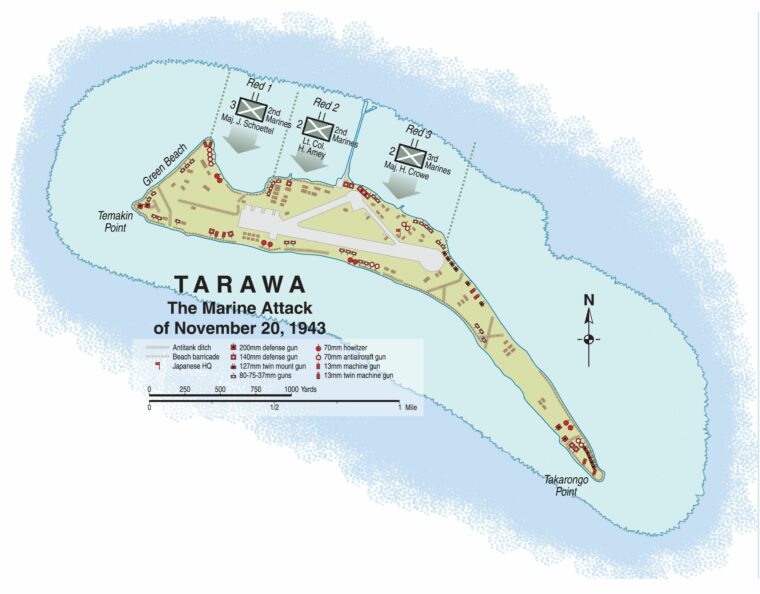

Shaped like a parrot, Betio is situated with its lagoon on the north side and the primary U.S. landing beaches, designated west to east as Red 1, 2, 3, running along the parrot’s breast. Near the junction of Red 2 and 3, a long pier jutted more than 500 yards into the lagoon, and undoubtedly the Japanese would set up machine guns and sniper positions there to harass any troops approaching land. For the most part, the primary beaches were convex, expected to ease the landings to a degree. One notable exception was a small cove on the west side of Red Beach 1 that would allow the Japanese to converge fire on the Marines from three directions.

Farther west, at a right angle to Red Beach 1, Green Beach ran the length of the parrot’s head from beak to crest. Intelligence reports suggested that the defenses along the Red beaches were not yet completed, and the waters of the lagoon would not be as rough as the open sea approaches to the ocean side of Betio.

Still, of greatest concern to the planners of the Tarawa assault was the existence of a barrier reef that ringed the islet. The most common landing craft in use with American forces at the time was the LCVP (Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel), or Higgins Boat, and these flat-bottomed transports were capable of hauling a 36-man platoon, a jeep and a squad of infantry, or the equivalent of 8,000 pounds of supplies.

Although they were shallow draft, about three feet aft fully laden, the depth of the water along the reef during tidal cycles might well be insufficient for the craft to enter the lagoon. If the LCVPs became hung up on the reef, infantrymen might be disgorged hundreds of yards from shore and required to wade some distance under enemy fire.

Lieutenant Colonel Robert Shoup, Operations Officer of the 2nd Marine Division, led the planning effort for the Tarawa assault. Choosing the primary landing beaches was simple enough, but Shoup recognized the peril the barrier reef posed to the LCVPs. He did, however, believe that a possible solution was at hand. Among the landing craft available to the Marines were a limited number of tracked amphibious vehicles originally developed for use in the swampy Everglades of Florida.

These vehicles, designated LVTs and commonly referred to as “amtracs” (and sometimes “amphtracs”) or “alligators,” were capable of powering through the water and then engaging tracks to climb across low barriers and land troops directly on the beaches.

Only 75 LVTs had been allotted to the Tarawa invasion, and Shoup requested the release of an additional 100 that were in storage on the U.S. West Coast. Holland Smith took up the cause and went toe to toe with Turner, who argued forcefully against the inclusion of more LVTs.

Turner reasoned that time was of the essence. Transporting the craft to a combat zone would require additional seaborne escort and possibly compromise the secrecy of Operation Galvanic. Smith persisted, and eventually the 100 LVTs were assigned to the deployed force. Half of these, however, would go to the Army’s landing operation at Makin. A total of 125 LVTs would be available at Tarawa. The rest of the combat transport burden would rest with the LCVPs.

During a senior-level conference at Pearl Harbor, Shoup’s original invasion plan was evaluated, and the architect was startled at the restrictions handed down by the highest echelon of Pacific command: A diversionary landing on an islet near Betio was cancelled. Although heavy bombers from the Ellice Islands had hit Tarawa repeatedly for days, the duration of pre-invasion naval and air bombardment on November 20 was restricted to preserve the element of surprise as long as possible. But perhaps the cruelest blow to Shoup was the pronouncement that the 6th Marine Regiment was to be held as V Corps reserve, lowering the Marine numerical superiority to only about two to one.

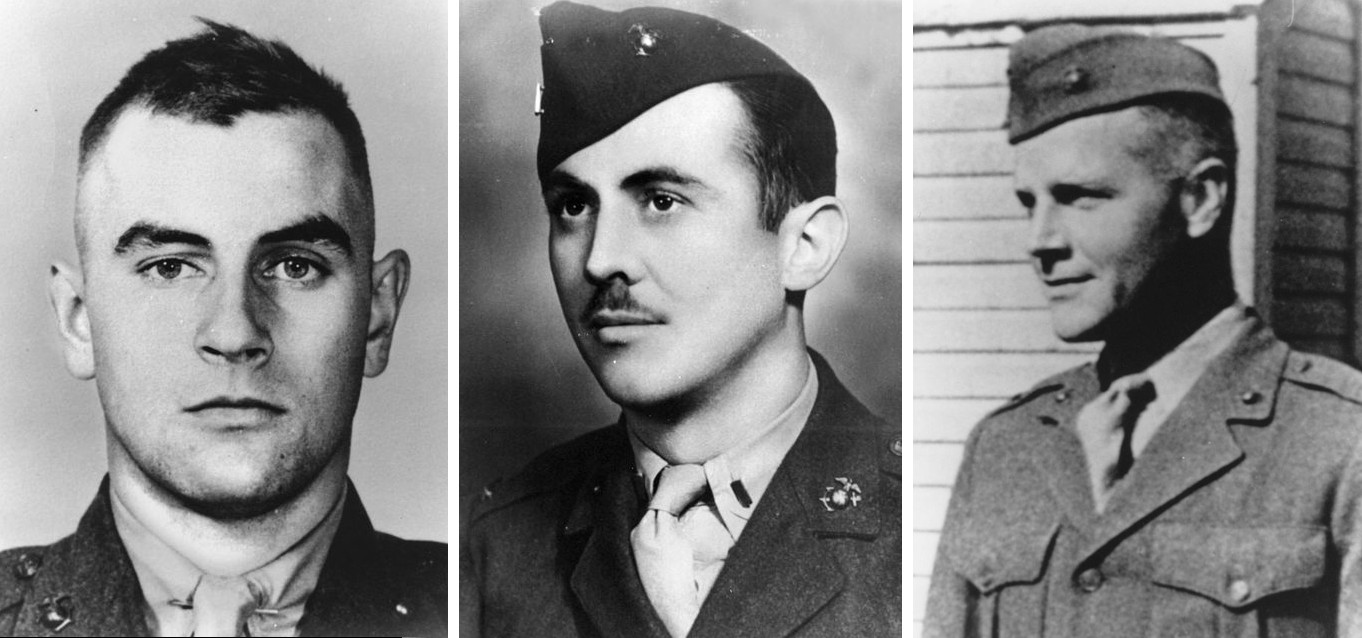

Thus, Shoup’s revised plan called for the 2nd Marine Regiment and a landing team of the 2nd Battalion, 8th Marines to hit the beaches, while the remainder of the 8th Marines served as 2nd Division reserve. On the eastern edge of the assault beaches at Red 3, the 2nd Battalion, 8th Marines (Landing Team 2/8), under Major Henry P. Crowe, would land simultaneously with the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marines (Landing Team 2/2) under Lt. Col. Herbert R. Amey, Jr., on Red 2, and the 3rd Battalion, 2nd Marines (Landing Team 3/2), under Major John F. Schoettel on Red 1. The 1st Battalion, 2nd Marines, under Major Wood B. Kyle, constituted the regimental reserve.

The first Marines to touch Tarawa would be the 34-man Scout Sniper Platoon, 2nd Marines, led by 1st Lt. William D. Hawkins, charged with seizing the long lagoon pier.

Shoup felt the considerable weight of the responsibility for planning the Tarawa landings; however, within days of the operation his burden became much heavier. Colonel William Marshall, commander of the 2nd Marines, suffered a serious heart attack just days before the assault. Shoup then became the logical choice to take field command and execute his own plan. Julian Smith promoted him to colonel and made it official.

Still agonizing over the challenge presented by the barrier reef, the new commander of the 2nd Marines told Time-Life Correspondent Robert Sherrod that the earliest of his assault troops would reach the beaches in amtracs but follow-up waves might run into trouble. “We’ll either have to wade in with machine guns maybe shooting at us, or the amtracs will have to run a shuttle service between the beach and the end of the shelf.”

In the predawn hours of November 20, steak, eggs, fried potatoes, and coffee were served up in the galleys of the transports carrying the Marines who would make the first major contested beach assault against entrenched Japanese defenders during the Pacific War. From the galleys, the Marines proceeded topside, then down cargo nets and into landing craft that bobbed below.

From the beginning, what had been conceived as a well-choreographed series of shelling, bombing, and strafing prior to the landings began to go awry. Admiral Hill became aware that some of the transport ships were actually in the wrong place and obscured the view of the gunners aboard the battleships and cruisers of the support force. He ordered them to relocate to the proper position while some Marines were still scrambling down the nets, and confusion ensued as transports and landing craft were separated.

A red star shell arced above Betio at 4:41 am, and at 5:07 the heavy Japanese shore batteries fired the first shots of the day. Minutes later, the big guns of the battleships Maryland, Colorado, and Tennessee opened fire. Some of the transports found themselves in range of the Japanese batteries and scurried to safer locations.

With H-hour set for 8:30 am, pre-invasion fire support was to begin with air strikes by planes from the carriers Bunker Hill, Essex, and Independence. Naval gunfire was to follow for just over two hours, and then a second wave of aircraft would strafe and bomb to keep Japanese heads low right up to five minutes before the first Marines landed. Actually, when Admiral Hill ordered his ships to cease firing at 5:42, he anticipated the appearance of aircraft. None came. For some unexplained reason, the strike was delayed half an hour.

After the Japanese received a reprieve of more than 20 minutes, Hill ordered his bombardment force to commence firing again. Five minutes later, at 6:10 am, the planes appeared overhead. The warships also took up their task once more and seemed to give credence to the boast of Rear Admiral Howard F. Kingman, who said, “Gentlemen, we will not neutralize Betio. We will not destroy it. We will obliterate it!”

The Marines in the landing craft were awed by the spectacular bombardment. A volcano of flame erupted on Betio when a shell from Maryland detonated the ammunition bunker of one of the heavy Japanese guns.

It looked as if no living creature could survive such a sustained rain of large-caliber shells. Looks, however, were to prove quite deceiving. Many of the naval rounds failed to penetrate the thick, reinforced walls of the Japanese bunkers, and these would have to be destroyed by Marines on the ground.

Due to strong currents in the lagoon and the general confusion, H-hour was postponed to 8:45 and then again to 9 am. Hill ordered his ships to continue their bombardment beyond the scheduled time, while aircraft were to maintain their support, striking targets inland from the beaches. However, the concussion of the first salvo from Maryland’s 16-inch guns caused a disruption in communications, and Hill’s order was in vain. Air support and naval fire were reported to have ceased 18 minutes before the Marines landed. Some accounts offer that Hill ordered a cease-fire at 8:54, fearing possible incidents of friendly fire. Aircraft remained in the vicinity and resumed their strafing attacks moments later.

The first amtracs began crossing the line of departure, 6,000 yards from the beaches, at 8:24 am, and one certainty during the tangle of confusion that preceded the assault was the gallant performance of the destroyers Ringgold and Dashiell, gliding into the lagoon as close as they dared without running aground and firing ahead of the Marines as long as they could without endangering their own men.

Three waves of amtracs churned toward the barrier reef followed by two waves of LCVPs. Japanese defenders on the ocean side began rushing toward the lagoon positions as reinforcements and, when the amtracs were within 3,000 yards, the defenders’ guns began to bark and chatter.

Lieutenant Hawkins and the intrepid Scout Sniper Platoon were five minutes ahead of the first line of amtracs. Unflinching in the face of heavy fire, Hawkins led the assault on the pier. His Marines followed, routing the Japanese with rifle, bayonet, grenade, and flamethrower. With his primary task completed, Hawkins was seen standing in an amtrac as it crushed barbed wire and beach obstacles and climbed the five-foot seawall near the water’s edge. From there he began to engage Japanese strongpoints.

As the first-wave amtracs reached the reef and ponderously climbed across, they were met by a torrent of deadly accurate Japanese fire. Private Newman M. Baird, a machine gunner aboard one of the craft and a Native American of the Oneida tribe, remembered the harrowing ordeal.

“We were 100 yards in now, and the enemy fire was awful damn intense and getting worse. They were knocking boats out right and left,” Baird recalled. “A tractor’d get hit, stop, and burst into flames, with men jumping out like torches…. Bullets ricocheted off the coral and up under the tractor. It must’ve been one of those bullets that got the driver. The lieutenant jumped in and pulled the driver out and drove himself ‘til he got hit. Our boat was stopped, and they were laying lead to us from a pillbox like holy hell…. I grabbed my carbine and an ammunition box and stepped over a couple of fellas laying there and put my hand on the side so’s to roll over into the water. I didn’t want to put my head up. The bullets were pouring at us like a sheet of rain. Only about a dozen of the 25 went over the side with me.”

Major Henry Drewes, commander of the 2nd Amphibious Tractor Battalion, climbed up to an LVT machine-gun position when the crewman manning it was killed. Within seconds, Drewes was dead from a bullet to the head. A sergeant stood up in an LVT on Red Beach 1, and his men watched as machine-gun bullets appeared to “rip his head off.”

The men of Major John F. Schoettel’s 3rd Battalion, 2nd Marines were being chewed up on Red Beach 1; several of their landing craft were hung up on the reef, forcing them to wade ashore in the face of intense Japanese fire. Schoettel believed his battalion had been decimated and was unable himself to get ashore for several hours.

Although his own Company L had taken 35 percent casualties while slogging toward Red 1 from the reef, Major Michael Ryan adapted to the situation and began to gather survivors of his command along with others he could assemble in a relatively quiet area that was actually on Green Beach.

At Red Beach 2, Corporal John Joseph Spillane was the crew chief of an LVT named The Old Lady, which reached the seawall and came under heavy fire. The Japanese tossed grenades at the amtrac, and Spillane, a baseball prospect that had brought scouts from the St. Louis Cardinals and the New York Yankees to his home, reacted instinctively. Accounts vary as to how many hand grenades he “fielded,” spearing, trapping, and throwing them back like a shortstop. There were at least three and as many as six that hissed his way.

“I didn’t have time to think. I just kept throwing them back,” Spillane remembered sometime later. “Finally, one came over with a lot of blue smoke coming out of it. I picked it up anyway, and just as I pushed back my hand to throw it went off. I was stunned for a minute. There wasn’t much left of my hand, but I felt no pain.”

Spillane’s baseball career was over. He held his bloody stump and yelled, “Let’s get out of here!” After recovering from his grievous wound, Spillane received the Navy Cross and Purple Heart and returned home to Waterbury, Connecticut. He worked for the Mattatuck Manufacturing Company and died at the age of 77 in 1996.

On the west side of the pier at Red Beach 2, Lt. Col. Herbert R. Amey, 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marines, attempted to rally his beleaguered men, raising his pistol and shouting, “Come on! These bastards can’t stop us!” In seconds, he was riddled with machine-gun bullets and killed. Lt. Col. Walter Jordan, an officer of the 4th Marine Division who had come along as an observer, took command of Amey’s battalion and quickly learned that one company was pinned down while another had lost five of six officers.

The only battalion to land relatively intact on the bloody morning of November 20 was Major Crowe’s 2nd Battalion, 8th Marines at Red Beach 3, east of the pier where Ringgold and Dashiell had covered their approach. Although much of Crowe’s complement was held up by a group of pillboxes and bunkers that included Shibasaki’s command post, two amtracs began pushing through to the edge of the 4,000-foot airstrip that crisscrossed the islet.

Meanwhile, Colonel Shoup was frustrated in his attempts to get ashore. Finally, sometime around 10:30 he transferred from an LCVP to an LVT and headed for Red Beach 2 near the pier. On its third attempt to land, the LVT was shot up and Shoup sustained a leg wound from a shell fragment. He limped shoreward, stood in water up to his waist, and began to piece the situation together. Communications were difficult at best as most radios were lost or waterlogged. Around noon, Shoup set up a command post about 50 yards inland from the pier and only three feet from a log bunker still occupied by Japanese troops. Neither could fire on the other.

Shoup received desperate reports on the situation from just about everywhere. “Have landed. Unusually heavy opposition. Casualties 70 percent. Can’t hold,” said one. He committed the regimental reserve, Major Kyle’s 1st Battalion, 2nd Marines, to land on Red Beach 2 and fight westward to Red 1.

General Julian Smith had already released Major Robert H. Ruud’s 3rd Battalion, 8th Marines from the division reserve after reporting to Holland Smith, “Successful landings on Beaches Red 2 and 3. Toehold on Red 1. Am committing one LT (Ruud) from Division Reserve. Still encountering strong resistance throughout.”

Kyle’s assault lost cohesion rapidly as LVTs were hit with accurate Japanese fire, several bursting into flames and sinking. Two companies were aboard these LVTs, but the weapons company was required to wade in. Five boats were pushed away from Red 2 by a hail of shells and wound up landing their troops at Ryan’s position on Green Beach. Kyle reached the pier and caught a lift from an LVT for the run-in. A relative few of his men succeeded in extending the tenuous American penetration a few yards inland.

Ruud’s command was cut to pieces when no LVTs were available to shuttle the Marines from the reef to the beach. The 3rd Battalion suffered 70 percent casualties wading through water that was chest deep. Two Higgins boats were obliterated on the reef by direct hits, and the coxswain of another was so terrified by the sight that he lowered his ramp shouting, “This is as far as I go!” Marines jumping off with full combat gear sank like stones and drowned.

The last of the division reserve, the 1st Battalion, 8th Marines, under Major Hays, was committed by Julian Smith sometime around midday after Holland Smith confirmed that the 6th Marines had been released from Makin and were heading toward Tarawa. A colossal communications failure resulted in Hays’s command remaining aboard landing craft all night long rather than coming ashore near Red 3 and working to the west as Julian Smith intended.

As casualties mounted and Japanese fire slackened only slightly, it became clear to the Marines pinned down at the seawall, in the shadow of the pier, or dug in along a narrow strip of sand that Japanese strongpoints would have to be cleared the toughest way possible––with demolition charges, grenades, and flamethrowers. Their dead comrades bobbed in the lagoon, burned out LVTs littered the shoreline, and the wounded lay about by the score. Those junior and noncommissioned officers that were left had to act.

Among the first of these to rise to the occasion was Staff Sergeant William Bordelon of San Antonio, Texas. A combat engineer coming ashore with Lt. Col. Amey’s 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marines, Bordelon reached Red Beach 2 after his LVT was hit, killing all but four of the men aboard. Bordelon prepared demolition charges and destroyed two Japanese pillboxes. As he took on a third position, he was wounded by machine-gun fire but emptied a rifle in support of Marines crossing the sea wall.

Bordelon then rescued two wounded men from the water. As he charged a fourth machine-gun position, he was cut down and died instantly. Bordelon received a posthumous Medal of Honor, the first of four Marines so recognized for valor during the fight for Betio.

The bodies of dead Marines floated in the lagoon and along the shoreline, while corpsmen and heroic Navy and Marine personnel risked their own lives to treat and evacuate the wounded. Among these was a Naval Reserve lieutenant from Minneapolis, Minnesota, named Edward Albert Heimberger, who pulled 47 severely wounded Marines from the water and helped 30 more get back to the ships for treatment. He received the Bronze Star with Combat “V” for heroism. Later, Heimberger went on to a notable acting career under the stage name Eddie Albert.

Although their combat training with armor had been virtually nil, the Marines knew that tanks could be valuable assets in reducing Japanese strongpoints on Betio. A company of 14 medium M4 Sherman tanks and a few light M2s of the 2nd Tank Battalion had been attached to the 2nd Marine Division for Operation Galvanic. The tanks headed for the invasion beaches at Betio aboard LCMs (Landing Craft, Mechanized) and ran into trouble just as the infantry units had.

Several LCMs were hit and destroyed by Japanese guns, taking their tanks to the bottom of the lagoon; none of the light tanks reached the shore. Shermans, too, fell into deep holes off the beaches and were lost, while several were thrown into the fight piecemeal with orders to simply engage any enemy position encountered. At least two were mistakenly put out of action by American dive bombers.

As the day wore on, only two Shermans remained in action. On Red Beach 3, a tank christened Colorado, under the command of Lieutenant Louis Largey, supported Major Crowe’s thrust toward the airstrip, taking punishment from Japanese antitank guns and even detonating a mine. Still, Colorado came on, blasting bunkers and pillboxes with its 75mm gun until its crew was at the point of exhaustion.

With Major Ryan at the extended position on Green Beach, a Sherman dubbed China Gal, commanded by Lieutenant Ed Bale, destroyed a Japanese tank after a hit from the enemy vehicle had turned the inside of China Gal’s turret lemon yellow but failed to penetrate the armor.

Japanese light tanks were no match for the American Shermans, but a pair of them rumbled toward Crowe’s embattled Marines. Two 37mm antitank guns had been wrestled to shore by their crews when the landing craft carrying them were sunk; the seawall blocked any further movement forward. Word was passed, and the shout, “Lift ’em over!” was heard. In seconds, the 900-pound guns were manhandled into position and fired. One of the Japanese tanks lurched sideways and belched smoke and flame––a direct hit. The other turned and fled.

Ryan realized that he was out of position, but as the number of men in his composite command grew, he sensed an opportunity. The Japanese defenses on Green Beach were sited to fire out to sea and vulnerable to flank attack. Marines moved from blockhouse to pillbox, from machine-gun nest to trench, and cleared a portion of Green Beach that might have been used to land reinforcements. However, there were no communications with Shoup to exploit the gains.

Ryan had little in the way of substantial weapons, no flamethrowers, and many of his demolition charges were expended in the fighting. Only the 75mm gun aboard the blackened hulk of China Gal provided anything heavier than standard infantry weapons. In danger of being cut off, he pulled back to a perimeter 200 yards deep and about 100 yards wide, an area he felt his makeshift command could hold against counterattack. His position was separated from Shoup’s command post by a 600-yard stretch of sand literally crawling with Japanese. Runners attempted to reach Shoup but failed.

To the east, the deepest penetration from Red Beaches 2 and 3 was 250 yards, about halfway across the airstrip. Elements of four Marine battalions stretched from left to right: Major Crowe’s 2nd Battalion, 8th Regiment; Major Ruud’s 3rd Battalion, 8th Regiment; Major Kyle’s 1st Battalion, 2nd Regiment; and the 2nd Battalion, 2nd Regiment under Lt. Col. Jordan after the death of Lt. Col. Amey.

As the end of that first bloody day approached, about 5,000 Marines had come ashore on Betio, and 30 percent of these were dead or wounded. The front line was not continuous. Pockets of Marines held positions that were often a significant distance away from the nearest supporting troops. They were well aware of the Japanese penchant for nighttime suicide charges, and the Marines knew they were vulnerable to such attacks. Sporadic gunfire pierced the darkness, but no attack came. Shibasaki’s communications had been severed, and he had lost contact with his subordinate commanders. Attempts to organize an attack that might drive the Americans into the sea proved hopeless.

During the night the Marines braced for the banzai charge that did not materialize. Some Japanese soldiers managed to reach the lagoon and swim to disabled LVTs and the hulk of a half-sunken freighter, Saida Maru, hit by American dive bombers earlier and capsized in the shallow water. From these positions, they waited to rake any reinforcements that ventured toward the Red beaches as dawn streaked the sky.

Aboard Maryland, Julian Smith was worried. “This was the crisis of the battle,” he remembered later. “Three-fourths of the island was in the enemy’s hands, and even allowing for his losses he should have had as many troops left as we had ashore.” Smith advised his superiors, Spruance and Nimitz at Pearl Harbor, in succinct, unvarnished fashion: “Issue in doubt.”

Hays and the 1st Battalion, 8th Marines were still aboard their landing craft almost a full day after initially boarding. Waiting at the line of departure, Hays had never received orders to land, and Julian Smith was shocked to learn later that the battalion had not come ashore. Through his assistant division commander, Brig. Gen. Leo Hermle, who had spent much of the day at the embattled pier, Smith learned that Shoup wanted Hays to land at Red Beach 2. Initial orders to go in on Red 3 were altered, and at 6:15 am, Hays’s men began the agonizing slog of 500 yards or more from the reef to Red 2.

The early hours of the second day were as costly as the first. The 800 men under Hays lost 350 of their number to murderous fire that poured from Japanese emplacements ashore and from the hulk of Saida Maru, even through repeated dive bombing and strafing by American planes. Shoup, weak from blood loss and exhausted from 30 hours without sleep, realized that Hays needed help and ordered a general attack along the intermittent Marine line. Two 75mm pack howitzers of Lt. Col. Presley Rixey’s 1st Battalion, 10th Artillery Regiment had been brought ashore during the night and assembled on the beaches behind a sand berm constructed by a Seabee bulldozer. They barked in support, suppressing some of the Japanese fire.

At Red Beach 3, Crowe and Ruud began to move despite the interlocking fields of fire from three Japanese bunkers on their left. Ringgold and Dashiell went to work once again, a direct hit from a five-inch gun blowing a bunker sky high. On Red 2, Jordan and Kyle directed their Marines in a push that reached the south shore of Betio, tenuously cutting the islet in two.

Though wounded on the first day, Lieutenant Hawkins, the quintessential Scout Sniper, was still full of fight. He had once pronounced that his platoon could whip any company-sized 200-man force in the field, and on the morning of November 21, few would have doubted it. Hawkins was ordered to silence a series of Japanese machine-gun nests and pillboxes that ringed a Japanese pillbox pouring deadly fire into Hays’s men near the small cove close to the junction of Red 1 and Red 2.

As his men lay down covering fire, Hawkins crawled toward a pillbox, fired through a gun slit, and tossed grenades inside. Screams were heard, and the Japanese weapons were silent––but not before Hawkins had been shot in the chest. He still refused to evacuate declaring, “I came here to kill Japs, not to be evacuated!”

Three more times, Hawkins led his men in successful attacks on Japanese positions. Then, he was caught in the explosion of an enemy mortar shell. Within minutes, he was dead. Some time later, Shoup remarked, “It is not often that you can credit a first lieutenant with winning a battle, but Hawkins came as near to it as any man could.”

The dashing Lieutenant William Deane Hawkins received a posthumous Medal of Honor for his bravery and remarkable leadership at Tarawa. He was 29 years old. Although his heroism had cost him his life, Hawkins had opened the way for Hays’s 1st Battalion, 8th Marines to seize the initiative on the right (west) flank of Red Beach 2.

Major Michael Ryan and company had been busy on Green Beach during the night gathering weapons, ammunition, and first aid kits from the dead and wounded. A second Sherman tank, Cecilia, had been repaired to join China Gal on the second day. There had been no appreciable Japanese resistance, allowing for some intermittent rest for the men who had braved the harrowing fight of November 20. Good fortune smiled on Ryan in the person of Navy Lieutenant Thomas Greene, a gunfire spotter whose radio actually worked.

At 11:20 am, Ryan moved across Green Beach with an organized and coordinated attack on the Japanese pillboxes and machine-gun nests there. Greene radioed coordinates to destroyers in the lagoon, and the 5-inch shells smashed into their targets with great accuracy. Within an hour, Green Beach was clear as Ryan’s patchwork command retraced its steps from the previous day. “Task Force Ryan” then turned toward the southwest corner of Betio to eliminate Japanese resistance there, moving into position to attack farther eastward toward the airfield.

Although communications had been sporadic, Ryan got word to Julian Smith aboard Maryland that Green Beach was open. The 6th Marines were arriving from Makin, and Smith ordered the regimental commander, Colonel Maurice Holmes, to prepare for landings. Holmes sent Major Willie K. Jones and the 1st Battalion to Green Beach and Lt. Col. Raymond L. Murray’s 2nd Battalion to the neighboring islet of Bairiki, where some Japanese had apparently fled. When Jones’s battalion reached Green Beach, it was virtually unscathed, with all its weapons and equipment intact.

By mid-afternoon, the situation had continued to improve. The Marines were gaining ground yard by yard, pillbox by pillbox. Reports began filtering into Shoup’s command post that some Japanese troops were turning their weapons on themselves. Shibasaki was desperate but resolute as the American artillery and naval gunfire crept closer. He exerted little control over his troops, and no reinforcements or relief could be expected.

About 4 pm, Shoup had gained enough confidence to send a situation report to Julian Smith. Its conclusion has become legendary: “Casualties: many. Percentage dead: unknown. Combat efficiency: we are winning.”

After dark, Colonel Merritt A. “Red Mike” Edson, already famous for his defense of Bloody Ridge at Guadalcanal, came ashore to relieve Shoup, whose stellar performance would earn him the Medal of Honor. Exhausted and in need of medical attention, Shoup, who went on to attain the rank of four-star general and serve as commandant of the Marine Corps, said to Robert Sherrod, “Well, I think we’re winning, but the bastards have got a lot of bullets left. I think we’ll clean up tomorrow.”

Edson set to work with efficiency. Orders for the third day were straightforward. The gains on Green Beach were to be exploited with renewed attacks to the east spearheaded by the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines, which was to link up with the 1st and 2nd Battalions, 2nd Marines that had fought their way southward the previous day. Hays’s 1st Battalion, 8th Marines was to thrust westward and eliminate the Japanese salient between Red Beaches 1 and 2. Crowe and Ruud, commanding the other two battalions of the 8th Marines, were to attack eastward.

With Cecilia and China Gal up front and supported by infantry, Major Jones and the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines made good progress, killing 250 Japanese troops and linking up with the 2nd Battalion Marines in about three hours. At Red Beach 2, Hays brought in half-tracks mounting 75mm guns when the light M2 tanks proved insufficient for the job of reducing some Japanese strongpoints. The 75s blasted away, and painfully slow progress against enemy positions around the cove required combat engineers with satchel charges and grenades to silence some of the persistent guns.

Crowe’s Marines faced the triple threat of a coconut-log bunker with multiple machine guns, a steel-reinforced pillbox, and a large blockhouse that was reported to have been Shibasaki’s headquarters. Their interlocking fields of fire had held the Marines at bay for two days. Finally, at 9:30 am, a mortar round scored a direct hit on the ammunition storage compartment for the coconut-log bunker, destroying the strongpoint. The Sherman Colorado, still in action, belched a 75mm round that cracked open the pillbox. The Japanese grip was loosened, but the blockhouse still spewed machine-gun and rifle fire.

Early on the morning of the third day, Shibasaki had sent a stout-hearted message to Tokyo. “Our weapons have been destroyed. From now on everyone is attempting a final charge. May Japan exist for 10,000 years.” His information was sketchy, and Shibasaki had no way of reorganizing a cohesive defense; however, the message was in keeping with the spirit of Bushido, the Japanese code of honor, and with his previous bravado. Now, if he was indeed inside the blockhouse, the Japanese commander did not have long to live.

The two-story structure was the highest point on Betio, and it had to be taken by storm. First Lieutenant Alexander Bonnyman of Knoxville, Tennessee, led five engineers forward under covering fire. Bonnyman traversed the sandy slope and reached the roof of the blockhouse only to be met by dozens of Japanese troops who had emerged to fight. Bonnyman made several of them human torches with his flamethrower and emptied his carbine into them. The Japanese pulled back in disorder, but the gallant engineer was killed.

As Bonnyman’s body tumbled down the slope, the remaining engineers planted demolition charges while Japanese troops swarmed out of the blockhouse. These hapless men were gunned down in minutes, and Colorado took out 20 of them with a single canister round. A Marine bulldozer shoved mounds of sand against stubborn firing slits. Gasoline was poured through ventilation shafts, followed by grenades. Explosives were detonated.

At last, the Marines on Red Beach 3 had silenced their greatest tormenter. More than 200 blackened Japanese corpses were later found inside the blockhouse. However, Shibasaki’s body was never positively identified. The 33-year-old Bonnyman received a posthumous Medal of Honor for his act of bravery.

Julian Smith came ashore on Green Beach about noon and quickly decided to move to the lagoon side of Betio near the pier where heavy fighting was still going on between Hays’s men and the Japanese along the edge of the small cove. Smith’s landing craft was shot up and its coxswain killed. An LVT was located for the general, and it was raked by machine-gun fire. Two hours later, Smith found Edson and Shoup. Attacks continued throughout the afternoon. Smith took formal command on the islet at 7:30 pm.

During the night at least four uncoordinated suicide charges rattled some of Major Jones’s positions, but the Marines held on in hand-to-hand combat, killing hundreds of Japanese troops. One Marine killed three Japanese soldiers with his bayonet and was stabbed with a Samurai sword by a Japanese officer whose skull was then fractured by a Marine rifle butt. The howitzers of the 1st Battalion, 10th Artillery fired more than 1,200 rounds, and gunfire from the destroyers Sigsbee and Schroeder broke the back of the Japanese, but Jones and the 1st Battalion, 6th Marines lost 40 dead and 100 wounded.

By the morning of November 23, the fresh 3rd Battalion, 6th Marines under Lt. Col. Kenneth McLeod was rolling eastward along Green Beach against diminishing resistance. Japanese combat proficiency had blown itself out with the previous night’s series of charges. At 1 pm, McLeod halted at the eastern end of Betio with nearly 500 dead or wounded Japanese in his battalion’s wake.

The Japanese strongpoints near the cove and the junction of Red Beaches 1 and 2 were still tough nuts to crack; they had played havoc with the Marines trying to come ashore on the first day. Majors Hays and Schoettel directed their 1st Battalion, 8th Marines, and 3rd Battalion, 2nd Marines, respectively, in attacks from three directions, while half-tracks provided suppressing fire from the reef, effectively encircling the troublesome pillboxes and machine-gun nests. Marine grit and Japanese suicides brought the situation under control.

Around 1 pm, a Navy Grumman F6F Hellcat fighter plane landed at the airfield on Tarawa that would bear the name of the deceased Lieutenant Hawkins. About the same time, resistance at the edge of the cove ended. Tarawa was declared secure after 76 hours of fighting the likes of which few men had ever experienced.

The veteran Lt. Col. Carlson admitted, “It was the damndest fight I’ve seen in 30 years of this business.”

Only 17 Japanese troops and 129 Korean laborers surrendered alive. A total

of 1,027 Marines and 29 U.S. Navy personnel, most of them corpsmen attached to Marine units, died in the fighting on Betio, and 2,292 Americans were wounded.

The lessons learned at Tarawa were bitter, but they actually saved lives during future amphibious operations across the Pacific. Among these were the clear implications that overwhelming numerical superiority against the defenders was a must, while the coordination of pre-invasion naval and air bombardment had to be improved. The big naval guns would only be effective against reinforced strongpoints with armor-piercing shells and plunging fire.

Solid information on the tides and depth of surrounding waters was needed for future operations. Amtracs would have to be available in quantity. Communications had to be improved, and the actual chain of command had to be clearly defined. On the ground, the Marines needed more automatic weapons and flamethrowers.

A public outcry followed Operation Galvanic. Newspaper headlines screamed of the high death toll, the cost of wresting a tiny mound of coral from its fanatical defenders. Admiral Nimitz and others were roundly criticized, but the Marines had been equal to the bloody task.

The military men had already known something the civilians had not previously reckoned. War is horrific business. They also knew that Tarawa was only the beginning.

There are a number of military historians that believe the Tarawa could have been bypassed as there was no way the Japanese could use the island for offensive operations and it was too distant from from the home islands to be resupplied. The division of the Pacific theater between MacArthur and Nimitz with their different approaches to the priority of objectives did little to help in decision making. The same situation arose on Peleliu when MacArthur insisted it be taken as a prelude to his invasion of the Philippines. The island was in even worse shape than Tarawa and was essential to neither Japan nor the US operation.