By David H. Lippman

On February 8, 1945, Lt. Gen. Sir Brian Horrocks climbed onto a platform halfway up a tree. From there, as he wrote later, “I could see in front of me a peaceful looking valley with small farms dotted here and there. On the far side lay the sinister Reichswald Forest. Over this valley 30 Corps were about to attack.” Horrocks’s men, watching one of the heaviest British artillery barrages of the war, expected a walkover. Instead, they would suffer some of the fiercest fighting of the war.

The Reichswald was the five-mile gap between the Maas and Rhine Rivers and the natural advance route from the German-Dutch border to the Ruhr. Since the British had closed on this sector in October 1944, Field Marshal Sir Bernard Law Montgomery had seen this valley of geometrically planted forests, towns, and small cities as the site for his next attack. It lay at the absolute right flank of the German West Wall defenses. Clearing it out would require a setpiece attack.

Montgomery planned the attack in two stages. First would be the British blast through the Reichswald. Next, south of the valley, the U.S. Ninth Army would strike across the Roer River a few days later, providing an anvil for the British Army’s hammer.

Monty’s plan to blast his way through the Reichswald was delayed, first by the necessity of opening Antwerp and the Scheldt Estuary to seaborne traffic, then by the Battle of the Bulge, which temporarily took 30th Corps away from the Reichs-wald to backstop the Americans on the Meuse River.

When the German offensive was defeated, Montgomery moved Horrocks’s 30th Corps back to its area in front of the Reichswald, assigning it to General Sir Harry Crerar’s 1st Canadian Army. Two Canadian divisions were added to the corps so that five divisions would make the attack. The five-mile assault area was extremely narrow. Horrocks wrote, “There was no scope for cleverness. I had to blast my way through.”

To support the offensive, the British and Canadians brought up their biggest artillery support of the war. Some 1,050 guns were to be used, including 576 field guns, 280 medium, 122 heavy and super-heavy, and 72 heavy antiaircraft guns.

The British planned a new addition to their bombardment, the Pepper Pot plan, which would feature all other division weapons that might be underemployed in the opening barrage, to maintain a volume of noise and high explosive on the German position. This barrage was made up of 188 Vickers machine guns, 80 4.2-inch mortars, 114 40mm Bofors guns, 60 Sherman tanks in a stationary role using their 75mm guns, 24 17-pounder antitank guns, 12 32-barrel rocket launchers, a grand total of 850 barrels firing in the Pepper Pot and 1,050 barrels in the “real” artillery.

This assemblage of guns was supported by more than a half million shells, a weight of some 11,000 tons. General Crerar told war correspondents that the munitions were the “equivalent to the bomb drop of 25,000 bombers.”

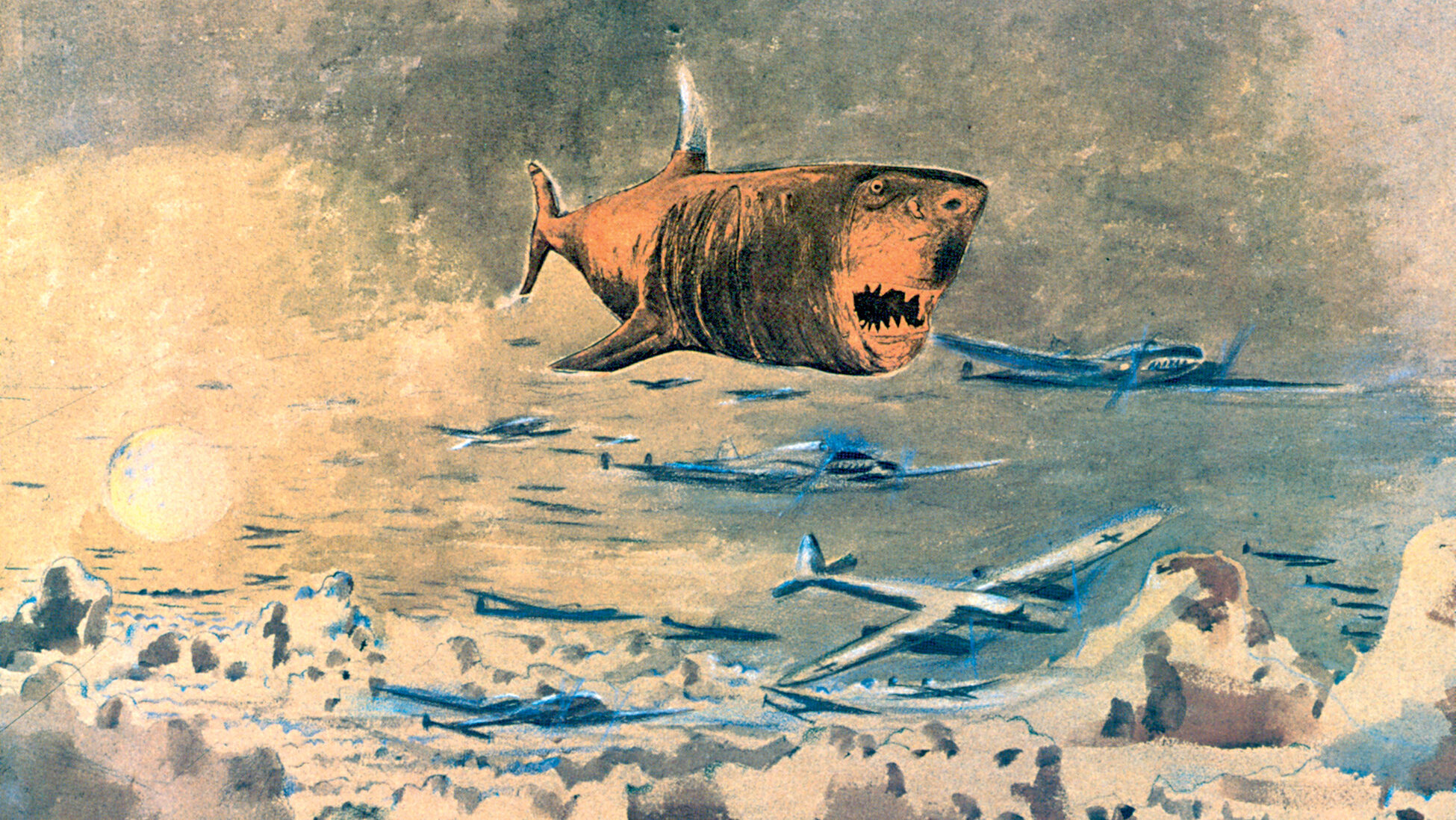

Bombers were present, too, in the form of the heavies of Royal Air Force Bomber Command and the U.S. Eighth Air Force, as well as the medium bombers of the 2nd British Tactical Air Force and the fighter bombers of RAF 83 and 84 Groups and the U.S. Ninth Air Force.

Also required for the attack were many different kinds of supplies, including 8,000 miles of four different kinds of cable, 10,000 smoke generators, a million gallons of fog oil, 750,000 maps, and 500,000 aerial photographs.

To mislead the Germans, the British and Canadians restricted movement by daylight and deployed dummy gun positions, which could be seen to be dummies. In the last 48 hours before the attack, the fake guns were replaced by real ones.

The deception measures worked. German intelligence reported, “Allied activities west of the Reichswald are intended to deceive us regarding the real center of gravity of the coming attack. It is possible a subsidiary offensive by the Canadians in the Reichswald area might be launched to draw our reserves but the appreciation that the main British attack will come from the big bend in the Maas is being maintained.”

By this point in the war, the Germans had virtually no strategy in the West—their armor had been destroyed in the Bulge—and their only plan was to hold the line.

The German Reichswald defenses were thin, consisting of the 84th Infantry Division and its two regiments and the 2nd Parachute Regiment, about 11,000 men. One of the defending battalions was a “stomach” outfit, made up of men with various stomach ailments, and another was made up of deaf men. The latter was held in reserve, as the Germans feared they might not hear British shelling and react accordingly.

Against this, some 200,000 British and Canadian troops, backed by 500 tanks and the 500 specialized vehicles of the 79th Armored Division, made up the assault force. But the Germans had several advantages despite their numerical inferiority. First, they were defending their West Wall fortifications, which provided them with plenty of defensive barriers, including the dreaded S-mines, wooden booby traps that set off an explosive charge that detonated at waist height. The Germans also had flooded the area north and south of the Reichswald, forcing the British into a narrow advance area.

The Germans could also call upon reserves that included veteran panzer and parachute divisions skilled in close combat and executing last-ditch stands. And the Germans were fighting for the first time on their home soil against a foreign invader, which was an additional motivating factor.

“It’s a typical Monty set-up,” wrote Canadian war correspondent Alexander McKee. “Bags of guns crammed on a narrow front, all your force at one point and bash in. Unsubtle but usually successful. Jerry knows you’re coming, but he can’t do very much because the gigantic bomber formations we wield will sweep it like a broom.”

At 5 am on February 8, 1945, both sides’ troops were awakened from their dugouts and trenches by the heaviest barrage employed by the British during World War II. The roar was heard for miles. At the same time, the Pepper Pot opened up, drenching the German front line to prevent movement of any kind, be it reconnaissance, supply, reinforcements, or merely a runner bringing up some hot breakfast.

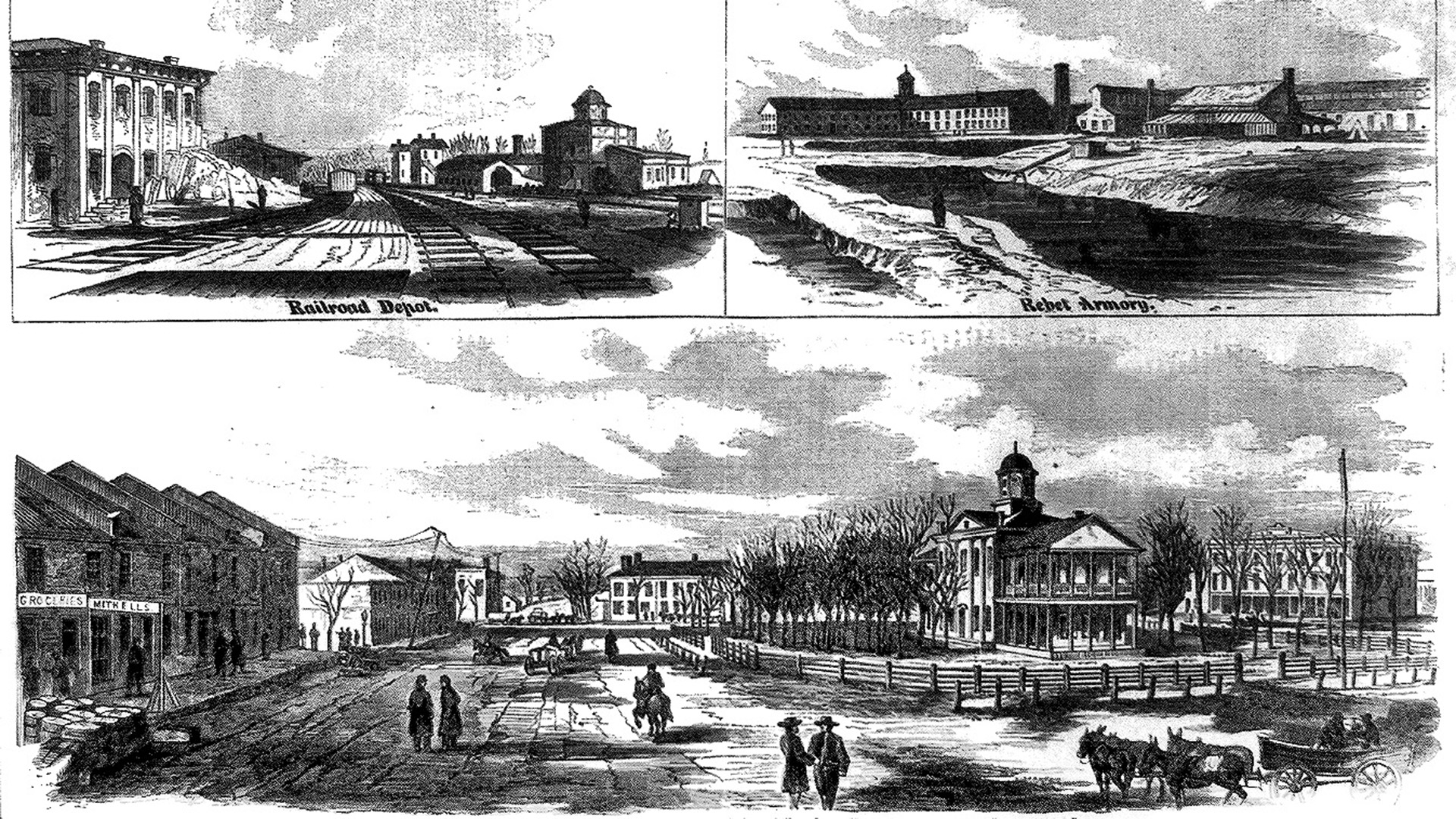

While the British artillery blasted the German defenses, Bomber Command and the U.S. Eighth Air Force hammered the towns of Cleve and Goch, dropping 1,400 tons of bombs on them, turning the towns to rubble.

The historian of the 4th/7th Royal Dragoons wrote, “It was a fantastic scene, never to be forgotten by those who were there; one moment silence and the next a terrific ear-splitting din, with every pitch imaginable, little bangs, big bangs, sharp cracks … the night was lit by flashes of every color and the tracers of the Bofors guns weaving fairy patterns in the sky as they streamed off towards the target.” Forward of the guns the ground shook continuously. Men were unable to speak and felt like they were being hammered into the ground.

The bombardment kept going for 21/2 hours and then stopped at 7:30 am. The only sound after that was the pop of smoke shells as a selected group of field guns built up a thick screen of smoke in front of the German first line, 13,500 yards long.

The Germans, seeing this screen, assumed the British were about to attack and began hurling artillery and mortar rounds back.

This was what the British were waiting for. Their artillery observers spent the next 20 minutes locating the German mortars and guns, and then the bombardment resumed at 7:50 am, blazing away at the selected targets.

At 10:30 am, the barrage switched to yellow smoke, and four British and Canadian divisions began the assault on the German defenses.

The advancing British troops expected the Germans to be pulverized but took no chances. Spearheading the advance were the specialized tanks of the 79th Armored Division, which included Crocodiles, Churchill tanks equipped with flamethrowers. Smaller Bren carriers equipped with flamethrowers were called Wasps. There were also Crabs, also known as Flails, which were Sherman tanks equipped with a device for beating the ground in front of them with whirling chains to set off antipersonnel mines, and Armored Vehicle Royal Engineers that could accomplish a variety of tasks. Some were equipped with powerful Petard mortars, which flung huge explosive charges. Others carried fascines, bundles of wood to fill in antitank ditches, or Bobbins, which were wound coil and tubular scaffolding carpets for laying a track over mud for wheeled vehicles.

The 79th had even more odd vehicles: Kangaroos, an early form of armored personnel carrier; Buffaloes, an amphibious tracked vehicle that could carry 24 infantry or an artillery piece; and Terrapins, the British version of the DUKW, a large, amphibious, wheeled vehicle for carrying men and supplies across water. It was a huge collection of specialized vehicles. The 3rd Canadian Division alone required 114 Buffaloes to cross the flooded terrain it faced.

But as the British troops went in, the first piece of bad news began to pelt the attackers in the form of a cold penetrating rain that would fall with little break for the next five to six days, turning the low and cratered ground into a quagmire and adding to the floods.

When the British attacked, they found the German defenses in disarray from the massive bombardment … dazed Germans emerging from ruined defenses, telling their captors of the complete disrupting of communications, of panic, and the breakdown of discipline as they thought they had been abandoned and were about to be overwhelmed.

In the north, the 2nd Canadian Division attacked south of its objective of Wyler and swung north to attack it from behind and the east. They found a stiff defense and suffered heavy casualties before Wyler was taken, at a cost of 15 dead to the Calgary Highlanders and two dead to the French-speaking Le Regiment de Maisonneuve. With that, the 2nd Canadian Division was squeezed out of the battle temporarily by the 3rd Canadian and 15th Scottish Divisions.

The 15th Scottish Division had a simple order “to break the Siegfried Line and take Cleve.” To do so, the 15th Scottish had considerable tank support, the whole of the 6th Guards Tank Brigade and its 178 Churchill tanks, two regiments of the 79th Armored Division’s “funnies,” two squadrons of flamethrowing Crocodiles, and the 2nd Household Cavalry Regiment. Against this were two regiments of German infantry dug deep in two lines of trenches covered by wire and mutually supporting machine-gun positions behind a wide antitank ditch.

Major General Colin Muir Barber, the seven-foot-tall commander of the 15th Scottish, had his two Highland Brigades lead the way on their narrow assault front. Two troops of Flails led the 46th Brigade on the right. The Glasgow Highlanders moved across the cleared tracks and rounded up 230 prisoners, but the Coldstream Guards lost several tanks in the deep mud while knocking out three antitank guns.

Behind them came the 9th Cameronians, which found few human defenders but plenty of mines and booby traps. They reached their first objective at 4 pm, but the supporting tanks were held up by the mud. At 5 pm, the Cameronians went in to attack their second objective, Frasselt, and the tanks finally arrived. The Crocodiles burned the houses, flushing German troops from the cellars. To Corporal Ian MacDonald of the Cameronians, “It was an awe-inspiring sight in the wintry gloom, the column of tanks grinding and rattling along and the great gush of flame belching and rumbling to incinerate its target.” In half an hour, the smoking ruins of Frasselt were in Scottish hands, along with an entire battery of 105mm guns and a tank destroyer.

The Cameronians struggled through minefields, with men getting legs and feet blown off, the wounded left in the freezing rain until stretcher bearers managed to struggle forward and get them out on small American Weasel carriers.

But the left attack, by the 227th Brigade, had more trouble. The 2nd Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders ran into heavy German fire. The left flank company lost all its officers. The company sergeant major then took command and continued the advance. The other leading Argyll company kept so close to the creeping barrage that they were able to capture Eisenhof and 80 prisoners together with a battery of 88mm guns without a shot being fired at them.

During the afternoon, the Scots Guards’ Churchills bogged down, but some were able to support the infantry. The Highland Light Infantry had the same problem with its supporting tanks—their Crab tanks bogged down in the mud. But by 6:30 pm, the 15th Scottish had achieved all its objectives, albeit two hours behind schedule.

The King’s Own Scottish Borderers’ regimental sergeant major hung out some token laundry on the West Wall fortifications, carrying out the promise of the old song of “hanging out the washing on the Siegfried Line.”

The attack went on into the gathering gloom of early evening. British searchlights bounced off low-hanging clouds to provide artificial light, and the Scottish troops could see the onion-shaped church dome of their objective, Kranenberg, ahead of them. Vicious house-to-house fighting ensued, and the Scots used grenades to clear out the defenders. By 5 pm, the garrison and 300 prisoners had been taken.

South of the 51st Division, the 53rd Welsh Division attacked into the forest against mounting German opposition. The 71st Brigade’s job was to take the Branden Berg feature, the high ground dominating the forest to the southeast. This would let 160th Brigade pass through and attack the Siegfried Line entrenchments by night with supporting Wasps—Bren carriers equipped with flamethrowers. Once through the West Wall, the Welsh would take the Stoppel Berg feature in the Reichswald’s northeast corner and secure the track along which the 43rd Wessex Division would move up.

With heavy artillery support, the 4th Royal Welch Fusiliers moved 1,000 yards ahead, turning the attack over to two supporting battalions, the 1st Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry and the 1st Highland Light Infantry. These battalions pressed on to the antitank ditch, where AVREs (Armoured Vehicle Royal Engineers) moved up and dropped bridges in two places. The infantrymen and supporting Churchill tanks charged across the two bridges and headed into the forest. The Churchill tanks kept going, even though the forest tracks were ridged with mountainous mud. The leading battalion burst into the forest to find a desolate scene of smashed trees, stinking cordite, and everything dripping wet from the pouring rain. Frightened German troops burst out of their battered trenches and foxholes, panic stricken and eager to surrender.

Horrocks, watching the attacks, marveled at the “stoicism of the youngsters,” calling them the “cutting edge of the vast military machine.”

The Welshmen continued to advance, finding the forest thicker and wooden blocks set up as tank obstacles, preventing the Churchill tanks from advancing. Private Dick Hughes recalled, “The long straight paths through the forest were death traps. The Germans had placed antitank guns and also had machine-guns sited among the fallen trees which made it near impossible to move forward.”

The determined Welshmen drove on, the Germans pulling back just as they were about to be outflanked. Private Phil Morris fought his way up the Branden Berg feature, a low hill defended by German paratroopers. “The Germans opened fire with a machine gun from a covered position that was so well concealed we hadn’t even seen it. We had no alternative but to leap into that stinking pool and it was bloody freezing. Three men tried to move to our right to outflank the machine gun, but the gunner saw them and they were raked with fire, killing one and wounding the others. While the gun was occupied with them, we threw several grenades which just exploded on the top in a cloud of earth and did no harm at all. But we immediately came under fire from another position to the left of the first one. I was sent back to our platoon commander to get a tank and scuttled back while the battle raged all around. The Captain was wounded but carrying on; he got a radio message back and a tank came up about a quarter of an hour later. It was guided to the problem machine-gun position by our sergeant and put a shell straight through the embrasure from about 70 yards away.”

By 3 pm, the Welshmen had taken the feature and found the artillery bombardment had demolished most of the German positions there.

The hardest fighting was seen by the 51st Highland Division, known as the Highway Decorators for their habit of marking everything they captured with their “HD” symbol.

They had to clear a wide sector from a narrow base, and the right flank’s assault, by the 154th Infantry Brigade, ran into trouble when snipers killed three Black Watch officers. Tanks dealt with the snipers, and the Gordons passed through, but their vehicles were held up at the antitank ditch. They only achieved their objective as night was falling.

The 153rd Brigade fought its way through minefields with the help of Crab tanks, which created a lane through the first minefield. An AVRE bridge-carrier dropped a bridge over the antitank ditch, which enabled important supplies to come up to the front, including 500 tins of self-heating soup.

The British had achieved their objectives, but the going had been slow because of the mud, and while the British took a lot of German prisoners the defenses had not cracked under the pulverizing bombardment. All night the battle continued.

That evening, the 15th Scottish sent in its reserve brigade, the 44th Lowland, ordered to attack while the other two brigades drew up more ammunition and fuel. Once the 44th Brigade had cleared up to Cleve, the British would commit the 43rd Wessex Division from corps reserve to the attack. It was an ambitious plan for one brigade, but it had plenty of artillery and tank support. However, the roads were rapidly being flooded, turning them to liquid.

The 44th Brigade loaded its men into Kangaroo APCs and trundled off behind Crabs at 9 pm. All night long the vehicles struggled through the muddy terrain, reaching the antitank ditch seven hours later. At 5 am, just before first light, the attack across the antitank ditch went in.

The Crab tanks rolled into the attack and immediately got bogged down in the mud. Three of them were completely useless. The three operable tanks struggled to beat two tracks to the antitank ditch, to enable the King’s Own Scottish Borderers (KOSB) to attack. An AVRE vehicle flung a bridge across the antitank ditch, and the British sent an antitank gun across as dawn started breaking. The antitank gun fouled itself on the bridge and blocked it completely. The attackers were now split, one company on the far side of the ditch, the rest on the near side. The British reacted by launching a sharp attack that took the two villages ahead of them and brought in a number of badly shaken POWs.

Next up for the 44th Brigade was the road leading to the important Materborn feature, and the Royal Scots Fusiliers moved through the KOSB positions to continue the advance.

Meanwhile, the battle continued to rage. The 3rd Canadian Division launched its attack over the flooded polder to clear the left flank by night. The Germans had earlier blown the main dyke at Erlekom, and the Waal River now flooded the extreme British left flank. The Canadian 8th and 7th Brigades, veterans of D-Day, advanced on Buffaloes, which “sailed” over the flooded terrain, with support from RAF and Royal Canadian Air Force Hawker Typhoons. The Canadians attacked their objective villages by night, backed by British tanks and artificial moonlight—searchlights reflected off low cloud. La Regiment de la Chaudiere, consisting of French-speaking Canadians, had to slog through waist-deep cold water, but they captured their objective, Leuth, in a dawn assault on February 9. The town of Zyfflich, surrounded by flooded water, was taken in two hours, and more than 100 Germans were flushed from cellars.

By first light on the 9th, the 3rd Canadian Division had captured all its first objectives and continued its sweep to clear the flooded Waal Flats completely, which secured the British left flank.

But Horrocks was worried. Mud and rain were putting the timetable behind. The rain was continuing to fall, and the water across the main Nijmegen-Cleve road rose by 18 inches in five hours. Unsurfaced roads and trails, damaged by shelling and heavy vehicles, turned into black porridge. Horrocks needed to get into Cleve quickly, before the Germans could rush up reserves to hold the town or counterattack. However, the supporting U.S. Ninth Army attack, Operation Grenade, was to be launched on February 10, and when it went in, it would draw off the German reserves. Determined to attack, Horrocks ordered his reserve division, the 43rd Wessex, to be ready at one hour’s notice to move from midday on February 9.

Meanwhile, the Germans assessed the British attack and its results. The 84th Infantry Division had had nearly six battalions destroyed by nightfall, and 86th Corps had suffered more than 3,000 casualties, including 1,200 POWs. British bombing had hammered the whole German defense system—even hitting the First Parachute Army’s headquarters, killing the general commanding the army’s artillery. The 84th Corps commander, General Erich Straube, had no trouble convincing General Alfred Schlemm, who headed the First Parachute Army that this was the main attack. Schlemm in turn was able to persuade the Army Group H commander, General Johannes Blaskowitz, to cut loose the 7th Parachute Division from reserves. But it was thinly spread and arrived piecemeal.

Studying his maps, Schlemm was gloomy—the only place it seemed he could stop the British offensive was at three hills just southwest of Cleve called the Materborn Feature, an obvious place to defend the Reichswald. The Germans raced to reinforce it, while the British moved to seize it.

Tasked to do so was the 44th Lowland Brigade of the 15th Scottish Division, which struggled through terrible road conditions. The 44th Brigade seized part of the Materborn Feature, the Wolfe Berg heights, by 11:15 am, taking 240 POWs and a medium battery. But by now the attack was 11 hours behind schedule. On paper, the 15th Scottish would send the two Highland brigades, rested and refreshed, back into the lead, but the jammed roads and muddy terrain meant that the 44th Brigade had to continue the attack.

Going 30 hours without sleep and 15 on the move, the 44th Brigade advanced in Kangaroos of the 1st Canadian Armored Personnel Carrier Regiment as far as the western slope of the Bresserberg Feature, seizing the high ground, taking 160 POWs and a battery of medium guns. As soon as the 44th began to consolidate its gains, the German 7th Parachute Division counterattacked from Cleve’s southwestern suburbs. All afternoon the Germans counterattacked but failed to recapture the height.

The Royal Scots Fusiliers attacked as well, into what was reported to be a formidable defense system, but the defending Germans were eager to surrender. Once again, as the British consolidated, they came under counterattack from the 7th Parachute Division.

By nightfall, the exhausted but triumphant Scots reported that they had “seized the Materborn Feature.” The 15th Scottish Division’s reconnaissance regiment probed past the heights and reported that the Germans in Cleve were still stunned and disorganized from the bombing and unlikely to offer resistance.

Horrocks, battling the terrain, the Germans, the weather, and a fever of 103 degrees, took the message and believed he could now unleash the 43rd Wessex Division to exploit the breakthrough.

But Horrocks was wrong. He committed his reserve too soon. He later said he did so because he was afraid of losing momentum. Instead of creating an offensive thrust, the 43rd Wessex Division began clogging the roads that the 15th Scottish was using to push forward. Soon both divisions were bogged down in mud and traffic jams.

Meanwhile, Horrocks’s other divisions continued their relentless advance in the quagmire. On the northeastern edge of the Reichswald, the 53rd Welsh Division’s 160th Brigade pushed on, now facing the 6th Parachute Division brought down from Arnhem. The roads behind the 53rd Division collapsed, further slowing the advance.

On the extreme right, the 51st Highland Division attacked the 2nd Parachute Regiment, which fought with the skill and determination of well-trained paratroopers. The commander of the Gordon Highlanders ordered his pipers to play the regimental march to ensure that other British troops would not fire on them in their moonlight attack. The 2nd Seaforths relied on more modern devices to overcome German defenses: the AVRE Petards and flamethrowing Crocodiles that supported their attack.

By the end of the second day, all objectives of phase one had been taken, and British POW cages were full with 2,700 captured Germans. Despite the delays due to traffic jams, weather, and mud, the British offensive was fairly successful. Now Horrocks revved up phase two, which would kick off on February 10 with the 51st Highland Division capturing Gennep and Hekkens, 53rd Welsh clearing out the Reichs- wald as far as the Cleve-Goch road, 43rd Wessex passing through the 15th Scottish to capture Goch, Udem, and Weeze, while the 15th Scottish captured Cleve. And while the British were accomplishing these hammer blows, the Germans would be tied down further by the massive American attack across the Roer River.

Except that the American attack did not happen. The Germans played their trump card on the massive Schwammenauel Dam, blasting open the inlet gate and jamming the outlet gate so that 100 million tons of water poured out of the dam and down the Roer River, creating a gradual flood. The river rose five feet. The American attack would be delayed by at least 11 days. Horrocks would have to clear the Reichswald all by himself.

To help him out, General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Allied supreme commander, committed two more divisions to Horrocks’s attack, the 52nd Lowland Division and the Guards Armored Division.

Meanwhile, the Germans were determined to hold their ground at all costs, as Blaskowitz ordered, saying that the consequences of a breakthrough to the Rhine were “incalculable.”

Blaskowitz committed his reserve, the 47th Panzer Corps, under General Heinrich Freiherr von Luttwitz. The corps had fought hard in the Bulge and was down to 50 tanks.

Now the 43rd Wessex Division’s 129th Brigade Group moved into the battle, struggling through gusting wind and icy rain. Much of the route was under water, and bogged vehicles on either side gave warnings as to the depth of the mud.

The column wound through the mud for hours, missing its turnoff in the dark and finding out where it was when German machine-gun fire ripped into it. The 4th Wiltshire leaped out of its Kangaroo APCs and with tank support cleared the roadblock. But the combination of mud, enormous bomb craters left in the initial bombing and shelling, and traffic jams held up the division’s advance, and the division’s boss, Maj. Gen. George Thomas, was laid low with a chill.

The Germans immediately counterattacked the 129th Brigade with the 16th Parachute Regiment—tough, well-trained men full of fight, backed by self-propelled guns and mortar batteries. The 4th and 5th Wiltshires fought back, defending against the Germans in mud-covered bomb craters, holding off the paratroopers.

Mud, disintegrating roads, rain, and traffic jams slowed the 43rd Division’s advance, putting the brunt of the attack back on the 15th Scottish Division, ordered to clear the bomb-cratered city of Cleve. Through hard fighting the Royal Scots Fusiliers were able to take the Cleverberg Hill, a mile and a half from the center of the city. But the British could not move any farther. They would have to wait a day to resume the attack.

On the left flank, Maj. Gen. Dan Spry’s “Water Rats,” the 3rd Canadian Division, had to delay its attack until 4:30 pm. The Stormont, Dundas, and Glengarry Highlanders sailed their Buffaloes straight to Donsbruggen and linked up with the 2nd Gordon Highlanders of the 15th Scottish and drove on to the next village, Rindern, for a five-hour battle, which lasted from midnight to dawn, with the Germans stopping the Canadians.

On the extreme right, the 51st Highland Division hit the main Siegfried Line defenses and found three large pillboxes constructed of two-foot-deep concrete reinforced with four-inch steel. The solution for all this concrete was to use smoke to isolate the pillboxes and then fire high-explosive shells directly into the embrasures. An AVRE Petard then came forward and launched its “dustbin” at the embrasure, blowing it in, opening a gap for the flamethrowing Crocodiles. Another defense line was taken by the 5th Camerons through a series of bayonet charges.

The third day of the offensive was a frustrating one for the British, with Cleve still in German hands, the German flank protected by the Roer floods, the weather still bad. But Crerar and Horrocks were determined to maintain the pace of the offensive, knowing that the Roer would drop and the weather would change. A quick victory was impossible, but a victory was inevitable.

Not if the Germans could help it, though. They committed the 116th “Greyhound” Panzer Division and the 15th Panzergrenadiers, both tough outfits, even if they were down to 50 tanks between them.

At dawn on February 11, the British resumed their attack, with the 3rd Canadian, 15th Scottish, and 43rd Wessex leading the way. The Canadians pushed up to the Spoy Canal and by midnight were along its west bank from the Alter Rhine south to the outskirts of Cleve.

The 15th Scottish, behind schedule, launched a two-pronged attack on Cleve with the 227th Highland Brigade on the left and 44th Lowland Brigade on the right. Before this could take place, the 44th Lowland had to relieve the 43rd Division’s 129th Brigade, which had been fighting all night. By 10:30 am, the Scots arrived and enabled the near exhausted 129th Brigade to get some rest. The men of the 129th staggered out of their positions, ate a hot meal, and then got their first real sleep in more than 50 hours.

Slowly and steadily, the 44th Brigade moved into Cleve backed by Grenadier Guards Churchill tanks. On their left, 227th Brigade advanced against panzerfaust antitank fire. As the day wore on, the Scots finally entered Cleve to find the venerable city an almost unrecognizable mass of ruined buildings, collapsed homes, and bomb craters. In their air raid shelters, the Germans had left behind vast stores of ham, fish, sausages, cheeses, pickles, and black bread, which the Scots found a welcome change from their own rations.

The Scots pushed through the city and found a damaged bridge over the Spoy Canal. Teams of sappers made the bridge usable for vehicles.

Meanwhile, the 43rd Wessex struggled on, launching a setpiece attack on the Materborn village with divisional artillery in support. The 7th Somerset Light Infantry took the village and kept driving east, frustrated by darkness at 5 pm, machine-gun fire, and heavy sleet. All night the Somersets continued to advance, gaining little ground. At dawn on the 12th, the 1st Worcestershires relieved the Somersets, attacked down the road to Bedburg, and overwhelmed the Germans in a series of rushes.

The 43rd had finally broken through the traffic jams and the craters of Cleve and were in a position to advance south to Goch. The immediate task was to seize ground southeast of Bedburg and use it as a start line to capture the village of Trippenburg, attacking on the 13th.

The 53rd Welsh Division resumed its advance on the 11th, moving through the Reichswald to its eastern edge. The 53rd, facing self-propelled guns firing straight down long ridges, protected themselves among closely planted trees. Despite casualties in men and tanks, the East Lancashires reached the Cleve-Asperden road by 6:30 pm. That night, the German 2nd Parachute Regiment tried a counterattack against the Welshmen, which failed.

On the right flank, the 51st Highland Division continued its advance on the 11th, pushing toward the German Siegfried Line defenses west of Goch. It took most of the 11th for the division to move up its 154th Brigade. By the time it reached the front line, there was an hour and a half of daylight left, so the Scots attacked with maximum artillery and Crocodile support. The 1st and 7th Black Watch moved from their start line so close behind the exploding shells that the stunned Germans had no time to recover before the Scots were on top of them. By 7 pm, the strongpoint had fallen and more than 200 Germans had surrendered.

The 1st Gordon Highlanders found the Germans had barricaded themselves in Gennep’s houses, so they used their distinctive street fighting technique. While mortar and machine-gun fire were directed against the front of a row of houses the infantry attacked each in turn through the back garden until the entire street had been cleared on one side. Then the opposite side was dealt with in similar fashion.

Now the Scots had to cross the Niers River, doing so with Buffaloes of the 79th Armored Division, which operated a ferry service all day long, wearing out the gearboxes of the mechanical troop carriers. The 5/7th Gordons were pushed across the river on the 11th. After a night in the workshops, the Buffaloes resumed the task, ferrying across another battalion of Gordons while Royal Engineers shoved a bridge across the Niers. The 1st Fife and Forfar Yeomanry’s Crocodiles lumbered across the Bailey Bridge into Gennep and burned out the last of the defenders.

By now the offensive was four days old and still behind schedule, but 30th Corps had reached positions from which the second phase of the battle could be mounted. The 15th Scottish were to advance from Cleve’s bombed ruins to Calcar, while the 43rd Wessex wheeled right and struck for the high ground north of Goch. Nearing the forest’s eastern edge, the 53rd would attack in an effort to grab the bridge over the Niers at Asperberg. On the southern flank the 51st Highland Division now had to cross the flooded Niers in force and clear the area to the south to mount an attack on Goch from the west.

After a morning of shelling, the British got down to business at 11 am, with the 15th Scottish’s 46th Highland Brigade leading the way backed with Canadian Kangaroos, Crocodiles, and self-propelled guns. They ran into trouble right away, losing two hours when one of the Churchills hit a mine on the muddy road, holding up the entire advance. At 1:30 pm, the attack was renewed and ran smack into panzerfaust and machine-gun fire. The British jumped out of their Kangaroos to attack just in time—four of the Kangaroos were knocked out by a self-propelled assault gun at the village of Qualberg two miles east of Cleve. The 7th Seaforths stormed the well-defended houses, killing 25 Germans and capturing 65 more, for a loss of 25 Scots.

Despite heavy German shellfire, the Scots pushed on to the next village, Hasselt, and came under more heavy fire. This time the Coldstream Guards’ armor moved in to engage German 88mm antitank guns amid the twilight gloom. As the sun set, the British commander on the scene decided to pull back his small force.

That turned out to be a wise decision because the Germans moved up a strong force. The British dug in for the night as the floodwaters reached their highest point. The 15th Scottish Division used DUKW Terrapins to establish a taxi service to haul supplies, food, fuel, and ammunition to the frontline troops.

Now Luttwitz was ready to counterattack. He had only 50 tanks, but they were Tigers and Panthers, superior to the British Sherman tanks. Luttwitz’s first plan was to counterattack and recapture Cleve, but the British were about to cut the Cleve-Goch road, so that did not seem possible. He decided to send both of his divisions into the Reichswald, where Allied numbers would be less effective in the dense terrain. The 116th Panzer Division would drive through Bedburg while the 15th Panzergrenadiers cleared the area from Cleve Forest down to the West Wall defenses in the southeastern quarter of the Reichswald.

Here stood the 53rd Welsh Division, which had continued its advance on the 11th and 12th. But that day it met violent counterattacks, which killed a 6th Royal Welsh Fusiliers company commander. The battalion’s CO raced to the spot and personally restored the situation, capturing 40 Germans and digging in east of the important Cleve-Goch road.

That afternoon the Germans counterattacked in force, preceding their infantry assault with heavy mortar fire. The 6th Royal Welsh Fusiliers and 1/5th Welch Regiment stood their ground until the panzergrenadiers were 300 yards away. Then the Welshmen opened fire and cut down the German attack.

The Welshmen held the ground but had taken heavy casualties. So had their supporting armor. The 9th Royal Tank Regiment lost 38 of 52 tanks and had to be withdrawn. Antitank guns were rushed up to hold the gains, but the Germans continued to counterattack. The only option was to maintain the pace of the offensive despite the miserable weather.

The 53rd Welsh attacked shortly after daybreak and found the Germans dug in on high ground. The 7th Royal Welsh Fusiliers took 70 casualties before it could crack the German position, and the hope of capturing the Asperberg bridge across the Niers intact was doomed when demolition charges exploded. The Welshmen had failed to achieve their final objective of the first phase, but they had done a tremendous job amid appalling weather and mud in six days and five nights of hard fighting, breaking through two lines of German defenses. In doing so, they also knocked out eight 88mm guns, large numbers of mortars and machine guns, several Mark IV tanks, and four Jagdpanther self-propelled antitank guns.

Meanwhile, the 15th Panzergrenadiers deployed tanks and self-propelled guns across the 43rd Wessex Division’s projected advance route. On the 13th, the Wessex men hit the Germans hard but took grievous casualties as it moved forward under German shellfire. Divisional artillery brought every gun to bear on the country ahead, and the 4th Wiltshires, supported by 8th Armored Brigade, advanced. One by one the tanks bogged down in the deep mud. The infantry charged on without them and seized their objective, the small village of Trippenberg, by nightfall. There, lacking armor or antitank guns, they awaited counterattack.

It took place the next morning. German panzers and panzergrenadiers stormed the village with heavy 88mm air bursts. One company of the 4th Wiltshires was overrun, but the rest held their ground.

That same day, the Allies finally caught a break. The sun shone from a brilliantly clear sky, and while the terrain was still muddy, the visibility was unlimited. In 24 hours more than 9,000 sorties were flown against the German defenses. Hawker Typhoon attack planes and Spitfires circled above the fighting troops, ready to attack targets.

The 46th Highland Brigade took advantage of the good weather to launch an all-out assault on the German blocking position three-quarters of a mile east of Hasselt. But the 7th Seaforths were “marooned” atop their heights by floodwaters that had reached to the tops of hedges. The 9th Cameronians and 2nd Glasgow Highlanders had to attack south to Bedburg to “find the enemy and destroy him.”

At 1:30 pm, backed by Coldstream Guards tanks, the Cameronians advanced against slim opposition, taking 30 POWs. The Glasgow Highlanders did less well, advancing through Moyland Wood and coming under heavy fire. The leading company was cut down to 40 men. German parachute infantry counterattacked, and the Scots had to withdraw under cover of smoke.

On the 46th Brigade’s left the Seaforths and their supporting Coldstreams set out, two companies up, along the water-covered road, at 9:30 am. The Churchills were stopped by mines, and the infantry went on, its pioneers lifting mines under fire, creating a path for the tanks, which moved in and hammered the German houses.

On the other side of the front, the 51st Highland Division drove the Germans off the high ground south of Gennep, moving into a position to attack Goch from the southwest. Straube rushed in 88mm guns to shell the British, followed by infantry counterattacks. Accurate 3-inch mortar fire stopped the German attack. On the 13th, Horrocks sent in the 32nd Guards Brigade, the infantry component of the Guards Armoured Division, to reinforce the 51st’s attack on the village of Hommersum, three miles southeast of Gennep. The 5th Coldstream Guards and 1st Welsh Guards lost a few men to mines but bagged a few dozen German POWs. The 3rd Irish Guards then passed through and seized Hommersum with little difficulty, taking 78 prisoners.

The 51st Highland Division maintained its attacks on Goch itself. The Niers bridge south of Hekkens was blown, so the Highlanders turned to their Buffaloes to ferry the infantry across, sending over two assault companies of Black Watch, swiftly reinforced by two battalions. Now, with the Niers behind them, the 51st was ready to attack Goch.

Meanwhile, the battle for Trippenberg raged on with the 5th Wiltshires resuming the advance at 11 am. The Wilts ran smack into heavy fire from machine guns, mortars, and 88s, which pinned down the left and center companies. The company on the right flank got into a hand-to-hand battle. Soon every officer of the battalion was a casualty. The wounded CO told his men to “dig in and hold,” and not until a new battalion CO arrived at 3 pm did he let himself be evacuated.

By darkness, the 5th Wilts were nearly exhausted, but the new CO decided that a night attack was needed to give the 130th Brigade a start line for the next day. The 5th Wilts fought their way through dark and heavy fire and pushed the Germans back. At dawn on February 15, the Wilts reached their objective with the loss of 200 men.

Now the 130th Brigade moved in for the next stage of the battle—and the weather went bad again, closing down British air support. The 130th attacked anyway, into heavy fighting.

On the night of February 16, the 53rd Welsh Division moved out of the southeast corner of the forest to clear the bridge area near Asperberg and the roads running east and northeast from it. The 53rd brought up four field and three medium artillery regiments to shell the Germans, some of the fire falling short. But the heavy barrage kept the Germans in their cellars and the Welshmen were on their objectives within two hours.

Some Germans hiding in their cellars burst out after the frontline troops had passed and attacked the second line of troops. One party of antitank gunners, signalers, stretcher bearers, and ammunition carriers was almost wiped out by German paratroopers, who charged firing from the hip. The British sent men back to clear the village, and it was not until 7 am on the 17th that the brigade was firmly established, at a cost of 73 casualties.

The same day the 160th Brigade cleared the whole area between the Reichswald and Cleve forests with no opposition. The next day the 71st Brigade closed up between the 43rd and 51st Divisions attacking Goch. The 53rd Welsh Division was finally done with the battle and began to pull out. It was the hardest battle of the war for the 53rd, with the division losing nearly a third of the 10,000 casualties it would suffer during the war in the hotly contested valley.

The 30 Corps as a whole had taken heavy casualties. Despite floods, rain, snow, mud, and the cancellation of Operation Grenade, the corps had achieved its objectives, admittedly behind schedule.

Horrocks himself had been a busy corps commander. With the troops following the prearranged plans, he had few decision to make—and the biggest one had gone badly. Despite his raging flu, he did the best thing a commander could do under the circumstances: made his way to brigade headquarters to give subordinates an opportunity to make requests, allow them to blow off steam, and encourage them in their efforts.

On the 14th, Crerar made a key decision. He separated the two Canadian divisions from 30 Corps and turned them back over to Lt. Gen. Guy Simonds’s 2nd Canadian Corps. Simonds was a cold, competent gunner, and by making the attack a two corps affair it would take some strain off the ailing Horrocks. The 30 Corps would attack Goch, while the 2nd Canadian Corps would attack Calcar.

On the 15th, the two Canadian divisions, along with the 46th Highland Brigade, reverted to Canadian control. Simonds sent the 3rd Canadian Division to pass through 46th Brigade’s positions in Moyland Wood to open the road to Calcar and committed the 2nd Canadian Division to take over from the 3rd Canadian at the right moment.

On Horrocks’s right flank, the 52nd Lowland Division dug in while the 51st Highland Division attacked the southern half of Goch. The 43rd Wessex would drive south-southeast to cut the Goch-Calcar road and then south to the escarpment overlooking Goch. Finally, the 15th Scottish would move through the 43rd Wessex to seize the northern half of Goch.

It looked good on paper, but the Germans had other ideas. When the 46th Brigade attacked, it was met with heavy mortar, infantry, and machine-gun fire. Despite mounting losses, the 46th drove the Germans off the westernmost knoll of Moyland Wood by 5 pm and then defeated a German counterattack shortly afterward.

The Highland Light Infantry advanced into dark and swirling mist that forced the tanks to be sent back. The accompanying guns bogged down in the mud. The leading two companies gathered up 80 POWs and reached their objectives before the Germans flung in a counterattack, which cut down the right-hand company.

On the 16th, the Highland Light Infantry tried to clear the eastern extension of the Moyland Woods, but German machine-gun fire was so intense the assault was stopped almost at its start line. The Cameronians attacked the easternmost knoll of the Moyland Wood and gained the heights just in time to take the inevitable German counterattack. The Cameronians maintained their offensive with the help of Wasp flamethrowers.

The same day saw the 7th Canadian Brigade attack east from the Bedburg area, with Scots Guards tanks, the Regina Rifle Regiment, and the Royal Winnipeg Rifles assigned the task of clearing high ground in the Louisendorf area. The German 346th Fusilier Battalion and 60th Panzergrenadier Regiment neatly fell back from the Regina Rifles, stopping them from crossing the road objective with their machine guns.

The Winnipeg Rifles, riding Kangaroos, advanced under a hail of shellfire from German reinforcements. The Kangaroos were slowed down by the shellfire, but the accompanying Scots Guards Churchill tanks reached Louisendorf alone. The Canadian infantry was reluctant to dismount until a Scots Guards captain, showing his disdain for danger, left his tank and walked from one carrier to another at the height of the shelling, encouraging the Canadians through example to get out and take their positions.

By dark, the Winnipeg Rifles were established in the town, digging slit trenches and sending back 240 POWs. Despite heavy German shelling, not one Canadian soldier was hit.

On the 17th, the Regina Rifles and Scots Guards tanks resumed their efforts to clear Moyland Wood, but German artillery fire was just too much for them. German 88mm fire detonated in the tops of trees, raining white-hot pieces of metal on troops below. At 4 pm, under cover of smoke, the infantry and tanks withdrew.

The 7th Brigade’s third battalion, the 1st Canadian Scottish, captured 150 German paratroopers but suffered heavy casualties. One Scots’ Guard tank broke down and had to be towed back. The driver was suspected of not having done his maintenance until the workshops crews opened the machine to find an unexploded 88mm shell lying amid torn-up transmission gears.

The Germans fought with skill and courage as usual, but one weapon made them break—the deadly flamethrower. However, the British and Canadians did not have enough of them. Moyland Wood refused to be cleared. By day’s end, the Regina Rifles had suffered 100 casualties, and the way to Calcar was still blocked.

The 30 Corps was also facing tough resistance. The fresh 52nd Lowland Division attacked on the extreme right, aiming to capture Afferden and cross an antitank ditch that ran east from the river and included the moated, medieval Biljenbeek Castle. The 5th Highland Light Infantry and 5th King’s Own Scottish Borderers attacked and were met with heavy mortar and machine-gun fire.

On the 17th, two battalions of the Highland Light Infantry attacked the Biljenbeek Castle with little success. The British brought up Churchill tanks, but the Germans knocked many of them out. A single company tried to rush a breach in the walls and was cut down.

Only when the weather cleared could the British break the castle. The RAF dropped nine 1,000-pound bombs on the castle and ripped it open. British troops stormed in to find its defenders numbered 15 paratroopers who had been kept supplied by rafts pushed across during the night. Their fanatical resistance, in spite of numerous surrendering Germans, showed that the Nazis were not giving up no matter how hopeless the situation.

The Guards Armored Division’s infantry resumed its advance on the 16th, but rain and mud cut the 19 supporting tanks down to two. For a week, the Guardsmen endured heavy shelling and incessant rain, which turned their section of the battlefield into something resembling Passchendaele.

After dark on February 16th, the 51st Highland Division resumed its drive eastward, relying on flamethrowers and rocket launchers to pave the way. At the same time, the last unengaged portion of the 43rd Wessex Division was finally able to pass through the mud and traffic jams. The 214th Brigade was hit by massive German gunfire as it was deploying. But the British hit back with nearly every gun in the 43rd Wessex Division’s inventory, laying a carpet for the 214th Brigade’s advance. The 214th began its attack at 4 pm and by dusk had advanced nearly 3,000 yards.

The British continued to attack with heavy artillery support as the night wore on. The 7th Somerset Light Infantry took 68 POWs and the commander of one German position. By 5:30 am on the 17th, the Somersets were consolidated on a 1,000-yard front along the escarpment overlooking Goch, having taken 180 more POWs. Six hours later the Somersets continued their advance.

At 11:30 am on the 17th, the 1st Worcestershires attacked, facing the heaviest and most accurate shelling of the war. By 6 pm, one observer remembered, “They were looking down on the chimneys of Goch along a front of 4,000 yards.” Horrocks would later call 43rd Wessex Division’s 8,000-yard continual advance the turning point of the Reichswald battle. With the 43rd Wessex Division in position, Goch would inevitably fall.

The Germans recognized this and sought permission to withdraw, but Adolf Hitler refused. The Allies had to be stopped and hurled back. Two additional battalions of the 6th Parachute Division were sent to take position between Moyland and Calcar.

On the 18th, the 1st Canadian Army prepared to attack the hinges of the German blocking line at Calcar and Goch. On the 19th, the 2nd Canadian Division rejoined the battle, sending in the 4th Canadian Infantry Brigade on Kangaroos supported by tanks. At noon, 14 field artillery regiments, seven medium regiments, and two heavy batteries opened fire. The tanks bogged down right away, and the infantry ran into 88mm antitank guns, which forced the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry to dismount from the armored personnel carriers short of its objectives. The Essex Scottish did better, taking its objective.

That night the Germans counterattacked with the Panzer Lehr Division, a crack outfit badly weakened from the Bulge. The Canadians were quickly overrun, and the 4th Brigade sent in its reserve battalion, the Royal Regiment of Canada. These troops quickly reported that the Essex Scottish headquarters was “held by enemy tanks and infantry.”

After being overrun, the Canadians regrouped and counterattacked at dawn, backed by tanks of the Fort Garry Horse. The Germans lost 11 tanks and six Jagdpanthers, forcing them to withdraw Panzer Lehr from the battle.

The relatively fresh 2nd Canadian Division attacked the eastern extension of the Moyland Wood, underestimating the defenders’ strength. A company of Canadian Scottish only 68 strong advanced against positions held by a parachute regiment. The Canadians were swept by heavy fire, and only nine men escaped.

Both sides gasped for breath on the 20th, and on the 21st the Canadians poured artillery and machine-gun fire into the Moyland Wood. The Royal Winnipeg Rifles, the Sherbrooke Fusiliers’ tanks, and three Wasp flamethrowers moved in to attack. Rocket-firing Typhoons made 17 separate low-level attacks. The paratroopers replied with heavy fire and counterattacks, which were beaten off. By the 22nd, the road to Calcar was finally open, the Moyland Wood cleared.

The Germans had lost men and terrain, but the Canadians had taken casualties: 400 men from the 4th Infantry Brigade, 485 from 7th Brigade.

Meanwhile, 30 Corps continued to attack. On the 19th, the 44th Lowland Brigade attacked toward the center of Goch with tank support. At 11 am, the British trundled off, and the point tank was just short of the inner antitank ditch when it was hit by a German antitank weapon and blown up. A second Churchill behind the lead tank was ditched, and the infantry had to clear the area for bridge-laying tanks. It took until 11:30 pm for AVRE fascines to be laid and the advance to continue.

Before dawn the 15th Scottish had a battalion well into northern Goch on the right and two small bridgeheads on the left.

On the 19th, the 5th Black Watch advanced into Goch, catching the Germans asleep in their cellars, including Colonel Matussek, the town’s garrison commander.

Fighting for Goch went on for two more days, with the 153rd Brigade taking the brunt. As the British cleared the town, the Germans could see that despite all their efforts there was no hope—the Roer flooding was receding, and soon the American offensive would be launched. The only move left was to withdraw to the Rhine.

So the Reichswald battle ended two weeks after it had started. The British had finally reached the lines they expected to take in three to four days, at a cost of 6,000 casualties, and the Germans still maintained a coherent front. The next stage of the attack would be the drive from the Reichswald to the Rhine—Operation Blockbuster.

On the 23rd, 1,000 American and British guns opened up in the U.S. 9th Army’s offensive over the Roer, and four U.S. infantry divisions stormed across the still turbulent waters, delayed more by the flooding than the Germans. It was the last stand-up fight between the Allies and Germans in Europe, and despite hard weather, soggy terrain, and German determination, the British had won their victory. Veritable had done its job. The Germans could fight for but not hold the Rhineland. The Anglo-American armies were headed for the Rhine.

That same day, Horrocks signaled his corps, “You have now successfully completed the first part of your task. You have taken approximately 12,000 prisoners and killed large numbers of Germans. You have broken through the Siegfried Line and drawn to yourselves the bulk of German reserves in the West. A strong U.S. Offensive was launched over the Roer at 0330 hours this morning against positions, which, thanks to your efforts, are lightly held by the Germans. Our offensive has made the situation more favorable for our Allies and greatly increased their prospects of success. Thank you for what you have done so well. If we continue our efforts for a few more days, the German front is bound to crack.”

David Lippman is a frequent contributor to WWII History. He also maintains a website dedicated to the daily events of World War II.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments