By Peter Kross

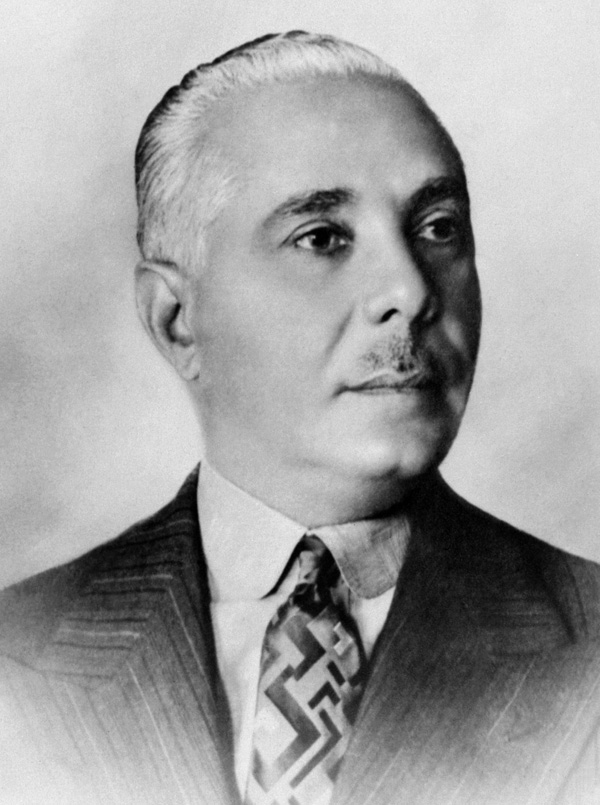

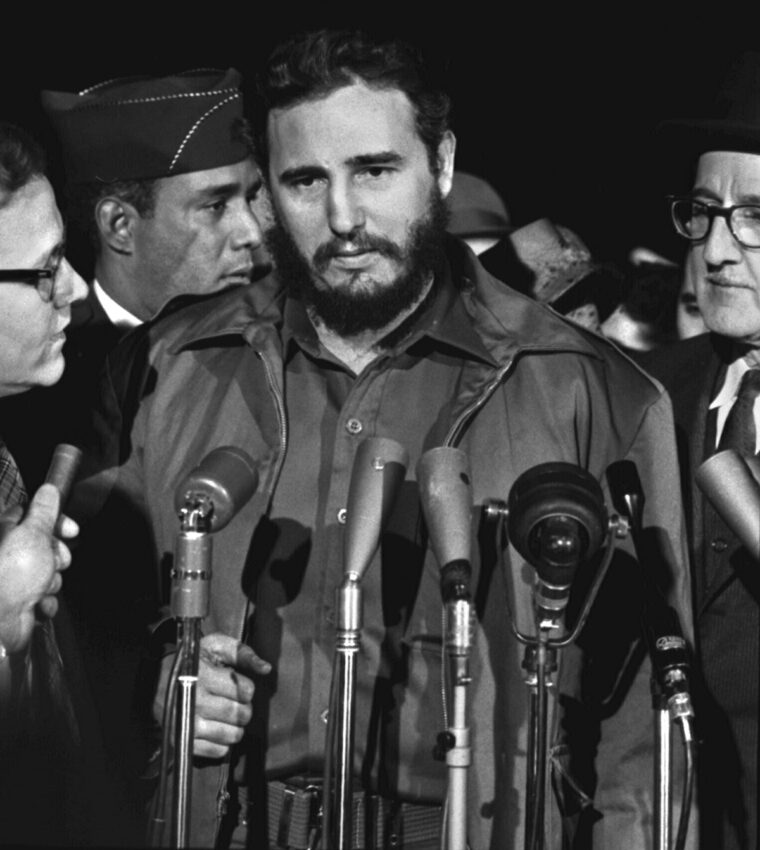

The United States from 1959 to 1961 turned its focus to two of the most charismatic, ruthless, and despotic rulers in the Caribbean region, Fidel Castro of Cuba and Rafael Trujillo of the Dominican Republic. Over the next two years, the United States government turned to the Central Intelligence Agency to devise a plan to kill both of these men, a task the agency relished. In the case of Fidel Castro, the CIA came up with hair-brained schemes to kill the Cuban leader, including using members of the American mafia to carry out the assassination. In the case of Trujillo, the CIA would ship arms and ammunition to certain anti-Trujillo elements in the Dominican Republic that were willing and able to assassinate their ruthless leader. In the end, the Castro assassination plots failed despite many attempts on his life. As far as the fate of Trujillo was concerned, the outcome was a lot different, with the conspirators having much better luck than their compatriots in Cuba.

In the years since the establishment of the Monroe Doctrine in 1823 by U.S. President James Monroe, the United States considered the Caribbean an “American lake,” an area of strategic importance to Washington. It was the policy of succeeding American presidents to prevent other powers, mostly from Europe, from gaining a foothold in Latin America. If it meant making marriages of convenience with less than stable leaders in the region to protect U.S. interests, so be it.

The United States had a longstanding political and economic relationship with the Dominican Republic going back to the early 1900s. In 1906, the Dominicans signed a 50-year treaty with the United States to give the larger country control over the republic’s customs department. U.S. Marines occupied the Dominican Republic in 1916 and stayed for four years. At the time of the American withdrawal, Trujillo was in charge of the Dominican National Guard. Only a few years before, Trujillo had been a member of group of dissidents who opposed Horacio Vasquez, the leader of the National Party. The group fomented a revolt in the country.

After the rebellion ended, the young Trujillo joined a rag-tag group of thieves and robbers called “The 44.” When the Americans landed in the Dominican Republic, Trujillo was one of hundreds of young men of military age who were given training by the United States, and he was part of the National Guard that battled the rebels in the countryside. Trujillo was a brutal soldier who took every opportunity to torture his prisoners without any retribution from his superiors. When Vasquez became president, he appointed Trujillo as a colonel in the National Guard and later chief of police, a post with unlimited power.

In 1930, a coup was initiated by the rebels whose leader, Estrella Urena, became the provisional president until elections were held. Trujillo pledged not to run for president but changed his mind. Backers of Trujillo killed opposition leaders, ransacked opponents’ homes, and kidnapped anti-Trujillo newspaper reporters. Through a campaign of widespread terror and intimidation on the part of his backers, Trujillo was now president of the Dominican Republic, a post he would hold for almost 30 more years.

In the decades to come, Trujillo ruled the country with an iron fist, taking over for his personal gain such industries as oil refining, cement manufacturing, and food production, pocketing large amounts of cash for years to come.

In 1956, Castro was planning a revolt in Cuba whose goal was the removal of the dictator Fulgencio Batista. Secretly, Trujillo offered Batista military supplies to stop Castro but there was never any lasting relationship between the two dictators. Trujillo referred to Batista as “that shitty sergeant,” and said, “I’m going to oust the bastard.” But Trujillo had no love for Castro either. Trujillo sent arms and ammunition to anti-Castro dissidents then living the Miami area. On New Year’s Eve 1959, Castro and his band of revolutionaries ousted the hated Batista, and Castro proclaimed himself the leader of Cuba.

On June 14, 1959, an abortive invasion to topple Trujillo began. On that day, a plane with Dominican markings left Cuba and landed at the Cordillera Central in the Dominican Republic. On board were 225 men led by a Dominican named Enrique Jimenez Moya and a Cuban named Delico Gomez Ochoa, both of whom were friends of Castro. The invasion force was composed of men from various Latin American countries and Spain. Some Americans also participated. As soon as the invaders landed, they were met by soldiers of the Dominican Army, and 30 to 40 men escaped.

A week later, another group of invaders boarded two yachts and was escorted by Cuban gunboats to Great Inagua, in the Bahamas, heading for the Dominican coast. Instead, the group was spotted by Dominican soldiers who blasted the yacht to pieces. Trujillo ordered his son, Ramfis, to lead the hunt for the invaders, and soon they were captured. The leaders of the invasion were taken aboard a Dominican Air Force plane and then pushed out in midair, falling to their deaths.

The plot was, in reality, tactically directed by many opposition leaders inside the country. Trujillo blamed Castro for the plot, and secretly Castro was behind the entire affair. In time, Trujillo set up a plan to invade Cuba (which never took place) and had his followers loot the Cuban embassy in the capital city of Ciudad Trujillo. Cuba subsequently severed all diplomatic relations with the Dominican Republic.

Another Caribbean leader who hated Trujillo was Romulo Betancourt, the president of Venezuela. In 1951, an attempt to kill Betancourt took place in Havana when someone tried to stab him with a poisoned syringe. The behind-the-scenes culprit was none other than Trujillo. By 1960, Betancourt was publicly criticizing Trujillo, calling him a crook and a scoundrel. In retaliation for his slurs, Trujillo planned an elaborate assassination attempt against Betancourt.

That same year, while Betancourt was driving through the streets of Caracas, Venezuela, during the annual Army Day parade, a powerful bomb exploded in his motorcade. The bomb had been placed in a green Oldsmobile parked near the parade route and contained 65 kilos of TNT. The blast exploded right under the car carrying Betancourt and his party. The car was sent flying across the street. One person in the auto was killed, and Betancourt suffered severe burns to his hands.

In Washington, the Eisenhower administration saw the assassination attempt by Trujillo against Betancourt as the last straw. President Dwight D. Eisenhower believed that Trujillo was just as bad as Castro, and if left alone he would turn the Dominican Republic into another bastion of communism in the Western Hemisphere. Eisenhower ordered the CIA to mount a covert operation to help the anti-Trujillo elements in the country to overthrow the bothersome dictator.

In February 1960, Eisenhower approved covert aid to the Dominican dissidents, which was intended to lead to the removal of Trujillo and his replacement by a regime that the United States could support. In the spring of 1960, U.S. Ambassador to the Dominican Republic Joseph Farland made initial contact with dissident elements in the country. The dissidents asked for sniper rifles, but at that time they were not delivered. Right before he left for Washington, Farland introduced his successor, Henry Dearborn, to the dissident leaders and told them that in the future they were to work with Dearborn. The new ambassador told the leaders that the United States would covertly help the rebels in their efforts to oust Trujillo but would not take any overt action.

In June 1960, a meeting took place between Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs Roy Rubottom and Colonel J.C. King, chief of the CIA’s Western Hemisphere Division. They discussed a request by a principal leader of the opposition for a limited number of arms to aid in the overthrow of the Trujillo regime. In July, their subsequent proposal was accepted, and the CIA sent 12 sterile rifles with telescopic sights along with 500 rounds of ammunition to the Dominican Republic.

In August 1960, the United States cut off diplomatic relations with Trujillo, leaving Dearborn as the sole U.S. representative in that nation. Dearborn was now the de facto head of the CIA in the Dominican Republic since all the regular CIA personnel had left the country. As Dearborn studied the political and military situation, he cabled Washington that the dissidents were “in no way ready to carry out any type of revolutionary activity in the foreseeable future, except the assassination of their principal enemy [Trujillo].”

In the meantime, the United States tried to aid in the peaceful removal of Trujillo by sending emissaries to persuade him to leave. The effort was to no avail.

Plans were now activated to effect the removal of Trujillo by any means necessary. A CIA memo concerning a limited invasion plan discusses “the delivery of approximately 300 rifles and pistols, together with ammunition and a supply of grenades, to a secure cache on the South shore of the island, about 14 miles East of Ciudad Trujillo.”

The dispatch also says that the cache would include “an electronic detonating device with remote control features, which could be planted by the dissidents in such a manner as to eliminate certain key Trujillo henchmen. This might necessitate training and introducing into the country by illegal entry, a trained technician to set the bomb and detonator.”

John F. Kennedy, who became president of the United States in January 1961, continued the CIA’s covert effort to oust Trujillo. Before the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in April 1961, the Kennedy administration covertly sent machine guns, pistols, and carbines to the dissidents in the Dominican Republic.

Three .30-caliber MI carbines had been left in the U.S. embassy before the United States broke diplomatic relations with Trujillo, and on March 31, 1961, these guns were supplied to the dissidents. These particular carbines eventually found their way into the hands of one of Trujillo’s assassins, Antonio de la Maza. On April 10, four M3 machine guns and 240 rounds of ammunition were sent via diplomatic pouch to the Dominican Republic. They were received on April 19.

On February 15, 1961, Secretary of State Dean Rusk sent a letter to President Kennedy informing him of the developments regarding the Trujillo plots. It read: “Our representatives in the Dominican Republic have, at considerable risk to those involved, established contacts with numerous leaders of the underground opposition … and the CIA has recently been authorized to arrange for delivery to them outside the Dominican Republic of small arms and sabotage equipment.”

After the Bay of Pigs disaster, the Kennedy administration tried to convince the dissidents not to kill Trujillo as the political climate was not conducive at that moment. However, the machine guns were dispatched to the U.S. consulate and were taken into possession by Dearborn. Two days before Trujillo’s murder, Kennedy sent a cable to Dearborn informing him that the United States did not condone political assassination in any form and that the United States must not be associated with the attempt on Trujillo’s life.

Dearborn’s pleas to the dissidents to call off the assassination proved, in the end, to be futile. On April 30, Dearborn told Washington via cable that the dissidents were going to kill Trujillo during the first week of May and had in their possession three carbines, four to six 12-gauge shotguns, and other small arms. The CIA, seeing the futility of further talks with de la Maza, ordered Dearborn to turn over the rest of the rifles.

On May 30, a spy who worked in the garage where Trujillo’s 1957 Chevrolet was parked, told the four main conspirators—La Maza, Salvador Estrella, Antonio Imbert, and Garcia Guerrero—that Trujillo was planning to meet his girlfriend, Mona Sanchez, that night. The men had in their possession revolvers, pistols, a sawed-off shotgun, and two semiautomatic rifles, some of which had been supplied by the CIA. The route that Trujillo was to take passed the Agua Luz Theater, on the highway that led to San Cristobal. The assassins were in position by 8 pm, waiting for Trujillo’s car to arrive.

At 10 pm, Trujillo and his chauffer got into the Chevrolet and proceeded to the girlfriend’s house. The assassins picked a section of the road that was the least traveled and when Trujillo’s car passed them, Imbert gunned his own car and took off after Trujillo. During the next few, hectic minutes, the assassins opened fire, riddling the car with almost 30 bullets. Trujillo’s chauffeur attempted to return fire with a machine gun.

Badly wounded, Trujillo scrambled out of the car, looking for the assassins. Meanwhile, De la Maza and Imbert doubled back. Trujillo had no chance. He was shot down by the two men and died on the spot. The conspirators put Trujillo’s body in the trunk of a car and parked it two blocks from the American consulate.

After killing Trujillo, the assassins fled to various parts of the country, hoping to evade the huge manhunt that was soon to descend upon them. Whatever hope the assassins had of a coup being initiated upon the death of Trujillo was for naught. His sadistic son and heir apparent, Ramfis, took over the presidency and rounded up all the conspirators. They were summarily executed, some of them being fed to sharks.

After the assassination, Dearborn sent a message to Washington saying, “We don’t care if the Dominicans assassinated Trujillo, that is all right. But we don’t want anything to pin this on us, because we aren’t doing it, it is the Dominicans who are doing it.” Shortly thereafter, Dearborn and the remaining Americans left Santo Domingo.

Ramfis Trujillo’s time as the leader of the Dominican Republic was short lived. By September 1961, he was in a power struggle with Joaquin Balaguer, another Dominican politician. A possible coalition government was proposed, but soon rioting broke out in the streets and the country seemed on the verge of collapse. In the end, Ramfis Trujillo fled his homeland with millions of dollars of looted cash, never to return.

A series of riots took place in Santo Domingo in April 1965. American embassy officials cabled Washington saying that communist elements were trying to take power in the country. President Lyndon Johnson dispatched a force of 22,000 American troops to restore order. In reality, there was no communist revolt, and the American invasion was roundly criticized throughout Latin America.

In the final analysis, the United States did not want to participate in the events leading up to the assassination of Rafael Trujillo but did so partly due to the political climate of the Cold War. The United States feared that Trujillo would turn the Dominican Republic into another Cuba and reluctantly went along with the rebels’ demands to provide them with guns and ammunition. In an ironic twist, the United States succeeded in removing one dictator, Rafael Trujillo, by basically doing very little, while desperately trying to assassinate Castro of Cuba, and failing miserably.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments