By Michael E. Haskew

The Allied planning for Operation Overlord had been ongoing for more than two years. Vast quantities of supplies and hundreds of thousands of fighting men and their machinery of war had crowded southern England. Then, on June 6, 1944, the Allied invasion of Normandy was unleashed.

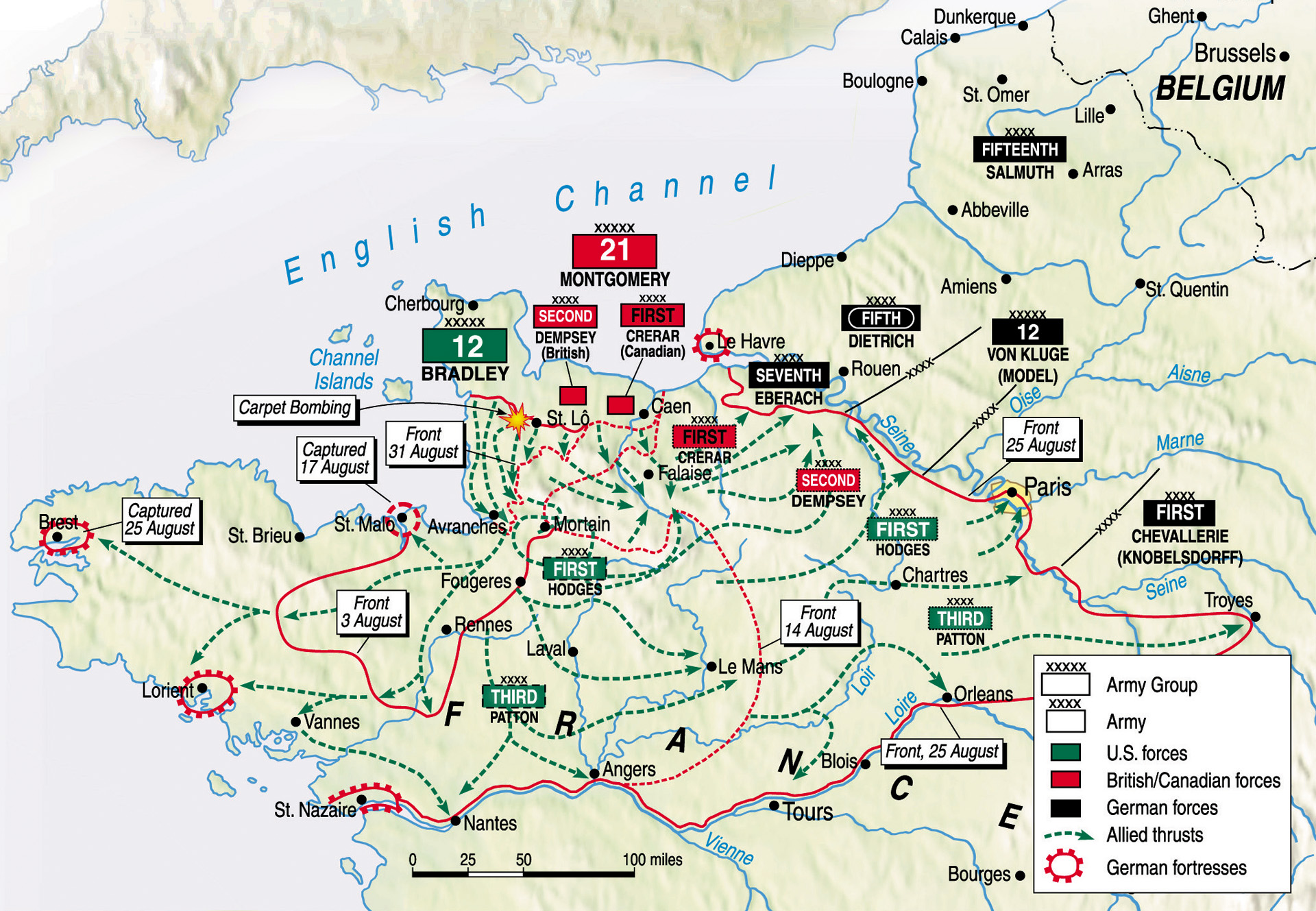

The expectations for Overlord were ambitious to say the least. Five beachheads were to be consolidated. In the east, the British were to capture the important road and communications center of Caen on D-Day, penetrating inland 20 miles. To the west, American forces were to slice across the Cotentin Peninsula and capture the major port city of Cherbourg in nine days. In less than two weeks the entire Allied penetration was to be at least 15 miles deep inside France along a line extending through Saint Lô and Caumont in the south and swinging eastward to Villers Bocage and beyond the mouth of the River Orne.

By the evening of June 6, however, it was apparent that the drive inland from the beaches would be an extremely arduous undertaking, costly in men and matériel. Tenacious German resistance and some of the most challenging terrain in the world impeded Allied progress to the extent that the specter of stalemate became quite real to senior commanders, who had pinned their hopes on a quick breakout from the extended beachhead in Normandy and rapid movement across open country, where tanks and armored vehicles could operate freely.

Cherbourg fell to troops of the U.S. VII Corps, under Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins, on June 27, two weeks behind schedule, and Caen was still in German hands at the end of the month; the British and Canadian soldiers of Lt. Gen. Miles Dempsey’s Second Army did not enter the town until the afternoon of July 9. Casualties were heavy. British losses neared 4,000 men, and the Germans lost at least 6,000 killed, wounded, or captured. Civilians died in great numbers as well.

Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, commander of all German forces in the West, and Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, commander of Army Group B, had deployed the bulk of their armored forces in the defense of Caen, realizing that the plain to the south of the town offered open country and rapid maneuver, while the terrain to the west and south was ideal for prolonged defensive operations and required fewer resources to hold the Americans at bay.

By early July, several German counterattacks had done little but to temporarily stabilize the front in Normandy. The Americans were bogged down and, although the British possessed most of ruined Caen, the Germans still held the high ground of Bourguébus ridge, where their artillery commanded the approaches and presented a significant obstacle to a breakout.

Still, both Rundstedt and Rommel realized that future offensive operations would only further deplete their limited resources. The troops of the German Seventh Army, under General Paul Hausser, and Panzer Group West, commanded by General Heinrich Eberbach, had been hammered by Allied ground forces, air power, and naval gunfire.

Hitler refused to transfer troops of the Fifteenth Army, 200,000 strong, from the Pas de Calais. The highest echelons of the German command remained convinced that Normandy was but a diversion and the main invasion effort was yet to come. Operation Fortitude, the creation of the fictitious First U.S. Army Group (FUSAG) around Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., had succeeded beyond the Allies’ wildest hopes and caused Hitler to withhold the resources that might have brought about a different outcome in Normandy.

Following a failed counterattack against the British and Canadians around Caen on July 1, Rundstedt telephoned Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, chief of the high command in Berlin. When Keitel asked what could be done to alter the deteriorating situation, Rundstedt bluntly replied, “Make peace, you fools! What else can you do?” Rundstedt was relieved the following day and replaced by Field Marshal Günther von Kluge.

Along with the stiff German defense, the land itself was a prominent adversary in the Allied effort. The hedgerows, or bocage, were mounds of earth with drainage ditches running alongside that stretched for miles between pastures and farmlands in Normandy. Centuries old, the hedgerows were often several feet thick with trees growing 15 to 20 feet high on top of them. The bocage was excellent terrain for defense.

The Germans concealed machine guns, antitank weapons, and snipers throughout the area, and the narrow country lanes became death traps to advancing GIs. Casualties were extremely high, and a day’s progress was often measured in yards. Armored vehicles were more or less restricted to the dirt roads and became easy marks for hidden enemy weapons.

General Walter Bedell Smith, chief of staff to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, remarked that in the south of Normandy “every small field was a fortress, every hedgerow a German strongpoint.” Indeed, the soldiers of the First U.S. Army, commanded by Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley, discovered just how horrific such close-quarter combat could be in early July. (Bradley led First Army in the Normandy campaign until August 1, 1944, when he became commander of Twelfth U.S. Army Group.)

After the fall of Cherbourg, Bradley reoriented the bulk of First Army southward and focused on two major objectives, the crossroads town of Saint Lô on his eastern flank and the village of Coutances about 15 miles to the west where five roads converged. Bradley amassed the strength of three corps, Collins’s VII in the center, Maj. Gen. Troy Middleton’s VIII on the right, and Maj. Gen. Charles Corlett’s XIX to the left. Eventually elements of 10 armored and infantry divisions were committed to the effort to take Coutances and Saint Lô and gain control of the highway that linked the towns.

The First Army offensive jumped off on July 3, and the going was rough from the start. Foul weather and determined German defenders ground the advance to a halt, and in 17 days of fighting the Americans suffered 40,000 casualties. The offensive faltered well short of Coutances, while Saint Lô fell to troops of the 116th Infantry Regiment, 29th Division on the afternoon of July 18. The bulk of First Army was now drawn up along the Saint Lô -Periers road, and Bradley conceded that the effort could go no farther. However, by that time he was already contemplating a renewed offensive to finally break out of the hedgerow country.

Bradley had spent hours in his headquarters tent poring over a giant map of Normandy and the surrounding countryside. He concluded that the best prospect for a breach of the German defensive positions lay in the concentrated use of air power to pulverize a rectangular area about 31/2 miles wide and 11/2 miles deep just beyond American lines along the Saint Lô-Periers road.

As soon as possible following the aerial bombardment, Collins’s VII Corps would strike. The 9th and 30th Infantry Divisions were to plunge through the weakened German lines and open the shoulders of a three-mile-wide corridor through which the 3rd and 2nd Armored Divisions and the motorized 1st Infantry Division would race. The initial objective was Coutances. German forces would be encircled and squeezed between the vise of VII and VIII Corps.

After reaching Coutances, the potency of the German resistance and momentum of the attack would be assessed, and American forces might indeed roll forward another 30 miles to Avranches, where the open country of Brittany stretched eastward.

The coordinated air-ground effort was code-named Operation Cobra. Originally set for July 18, bad weather forced several delays, and Cobra did not get under way until the morning of July 25.

Eisenhower was enthusiastic about Cobra, as was General Bernard Montgomery, commander of 21st Army Group and all Allied forces in Normandy, who had called a conference at his headquarters in Creuilly on July 10. It was there that Bradley first broached the idea of Cobra with Montgomery and Dempsey. Montgomery knew that Bradley needed time to resupply and reallocate his forces; therefore, he initially proposed that the British in the Caen sector continue to keep the vast majority of German armor and mobile reserves occupied, drawing them away from the Americans to allow the greatest potential success for Cobra.

At the conclusion of the July 10 meeting, Dempsey suggested that the British might do more than simply serve as the immovable base for the upcoming offensive. Second Army might launch another offensive of its own. Montgomery agreed and ordered Dempsey to plan for an attack, codenamed Operation Goodwood, which would involve the troops and armor of three corps.

In the center of the thrust, three armored divisions of the British VIII Corps—the Guards, 7th, and 11th—would attack toward Falaise and the open plain of Brittany. The Canadian II Corps was to secure the portion of Caen that remained in German hands near the River Orne and the surrounding high ground. Meanwhile, XII Corps was to conduct preliminary operations as a diversion. Montgomery and Dempsey concluded that if Goodwood were completely successful, the British offensive might reach beyond Falaise and as far south as Argentan.

Air power was expected to play a critical role in Goodwood, and more than 2,100 planes, heavy bombers of the U.S. Eighth Air Force and Royal Air Force Bomber Command along with the tactical fighter bombers of the U.S. Ninth Air Force, opened the offensive on the morning of July 18, dropping more than 8,000 tons of bombs on German positions. Royal Navy warships in the Bay of the Seine added their guns to the effort.

Confronting the British were the 13 divisions of Panzer Group West, organized into four corps, under Eberbach. These troops held a 70-mile line with the bulk of their strength, five divisions at the front and five in reserve, around Caen. Eberbach arranged his defenses in three lines to a depth of 1,200 yards. The 88mm guns of the III Flak Corps were positioned to deliver devastating artillery fire, and rocket launcher brigades supported each corps.

Although he expected a British attack, Eberbach was surprised that Montgomery moved with such speed on the 18th. When the VIII Corps armor rolled forward, the tanks made good progress. Only when they reached the concentrated German antitank and artillery positions along the third defensive line was their momentum slowed. British problems were compounded by the narrow field of maneuver afforded the tanks and the tenacious defense put up by German infantry and armor in small towns and villages, upsetting the offensive’s timetable.

By late morning, Eberbach had committed four infantry and four armored battalions of the 21st Panzer and the 1st SS Divisions to deal with Goodwood. The 13 PzKpfw V Panther tanks of the II Battalion, 1st SS Panzer Regiment engaged 60 British tanks southeast of the village of Soliers and destroyed 20 of them. Kluge finally received help from the Fifteenth Army, when the 116th Panzer Division was released as reinforcement.

The Germans successfully prevented a direct breakthrough but had given ground and exhausted their reserves in the effort to contain Goodwood. The British lost 270 tanks and 1,500 casualties on July 18, renewed the attack on the 19th, and lost another 131 tanks and 1,100 killed, wounded, or captured, and then ground to a halt on the 20th as heavy rains turned roads into rivers of mud. The 500 tanks lost during Goodwood amounted to 36 percent of the entire British armored force available in Europe. One armored regiment had lost 57 of its complement of 61 tanks.

In exchange for the butcher’s bill, the Canadian II Corps had cleared all of Caen and moved modestly onto the plain southeast of the town, while the VIII Corps had managed to gain control of 34 square miles of territory.

To this day, controversy surrounds the true intent of Operation Goodwood—to achieve a breakout or to erode German combat efficiency in order to aid the American Cobra offensive. Montgomery may well have attempted to hedge his bet on the outcome. Prior to July 18, he had assured Eisenhower that the eastern flank of the German line would “burst into flame.” The “whole weight of air power” might bring about “decisive results.” Then, on the evening of July 18, he raised the stakes by issuing a battlefield communiqué that asserted, “Early this morning British and Canadian troops of Second Army attacked and broke through into the area east of the Orne and southeast of Caen.”

Four days earlier, Montgomery had written to Field Marshal Alan Brooke, chief of the Imperial General Staff: “And so I have decided that the time has come to have a real ‘showdown’ on the Eastern flank … into the open country around the Caen-Falaise road.” Nevertheless, Montgomery sent an aide to the War Office to explain vaguely that the object of Goodwood was to “muck up enemy troops” and “at the same time … to take advantage of … the enemy … disintegrating.”

Despite the fact that Goodwood succeeded in rendering as many as four German divisions ineffective by the time Cobra was launched and depleted German armor substantially, Eisenhower had expected more. The furious supreme commander came close to relieving Montgomery, and there was plenty of support for such a decision from senior commanders both British and American. Among Monty’s leading detractors was Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder, the deputy supreme commander, who alleged that Montgomery had never actually intended a breakthrough and had misled Eisenhower. A group of senior British officers urged Montgomery’s removal due to a “serious lack of fighting leadership.”

In the end, Eisenhower chose to retain Montgomery, writing a letter to the 21st Army Group commander expressing his disappointment that the hoped-for breakout “did not come about.” Eisenhower further urged Montgomery to renew offensive operations in support of Bradley’s offensive. The hope for an Allied breakout in the summer of 1944 now depended substantially on the success of Operation Cobra.

On July 12, Bradley stood before his staff and corps commanders and raised the curtain on Cobra. He said bluntly of the Germans, “If they get set again, we go right back to this hedge fighting, and you can’t make any speed…. This thing must be bold.” Bradley further explained that a rapid breakout from the “slugger’s match” in Normandy was to be achieved with the aid of “three or four thousand tons of bombs.”

“Lightning Joe” Collins’s VII Corps staff went to work. Since the 9th and 30th Infantry Divisions had both been depleted by weeks of combat, Collins requested the 4th Infantry Division for added strength during the ground phase of Cobra, and under his direction the plan of attack evolved.

“The Cobra plan in final form,” wrote historian Martin Blumenson, “thus called for three infantry divisions, the 9th, 4th, and 30th, to make the initial penetration close behind the air bombardment and create a ‘defended corridor’ for exploiting forces, which were to stream westward toward the sea. The motorized 1st Infantry Division, with CCB (Combat Command B) of the 3rd Armored Division attached, was to thrust directly toward Coutances. The reduced 3rd Armored Division was to make a wider envelopment. The 2nd Armored Division, with the 22nd Infantry attached, was to establish blocking positions from Tessy-sur-Vire to the Sienne River near Cérences and, in effect, make a still wider envelopment of Coutances.”

Bradley counted on the saturation bombing to soften up the German positions considerably, and on July 19 he traveled to the headquarters of Air Chief Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory, the overall air commander, to discuss the plan. Bradley stressed the need for a “blast effect” and suggested the use of 100-pound fragmentation bombs and nothing heavier to avoid the deep cratering of roadways and routes of advance that had hindered earlier Allied offensive efforts in Normandy.

He further suggested that the bombers take a lateral approach to the designated area, flying parallel to the American line rather than over the heads of the ground troops. This would allow the bombers to operate with the sun at their backs. Finally, Bradley compromised with the air leaders, agreeing to lengthen the distance the troops would be pulled back from the bombing zone from 800 yards to 1,200. Still, this left virtually no margin for error for the bombardiers; the air commanders had originally requested a distance of 3,000 yards.

The saturation bombing was to begin 80 minutes prior to the jump-off of the ground offensive. The first to go in would be 350 fighter-bombers that would strafe and bomb the area for 20 minutes. Then, 1,800 heavy bombers of the Eighth Air Force would deliver their payloads for the next hour. Another 350 fighter-bombers were to hit the area again for 20 minutes, and the final blow was to be delivered by 396 medium bombers against the southern half of the rectangle in a 45-minute air assault. Altogether, with 500 fighters flying top cover, 2,500 planes were to attack the designated area for two hours and 25 minutes, dropping 5,000 tons of ordnance.

Stretching across the path of Operation Cobra was the German LXXXIV Corps under General Dietrich von Choltitz. The LXXXVI Corps consisted of the understrength remnants of several divisions, including the 243rd, 91st, 77th, 265th, 2nd SS Panzer, 17th SS Panzergrenadier, 5th Parachute, Panzer Lehr, and others. Along with the adjacent II Parachute Corps, the number of German defenders in the area approached 30,000.

Panzer Lehr, holding a three-mile front along the Saint Lô-Periers road, was in Cobra’s crosshairs and would receive the brunt of the Allied aerial bombardment. At full strength, Panzer Lehr was authorized to field 15,000 men and 200 tanks and armored vehicles. Battered in Normandy, the division could muster only about 2,200 fighting men and 45 armored vehicles as Cobra neared.

The Germans’ troubles in Normandy worsened on July 17 when Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel, returning to Army Group B headquarters in La Roche Guyon after a meeting with 1st SS Panzer Corps commander Sepp Dietrich in St. Pierre-sur-Dives, was seriously injured when a Spitfire from RAF 602 Squadron strafed the open Horch staff car near Livarot and caused it to crash. With Rommel hors d’combat, the German Army in the West lost one of its ablest leaders.

Since the opening act of Operation Cobra was the aerial phase, Leigh-Mallory retained the right to set the starting time. Bad weather began to clear on July 23, and the air marshal ordered the bombers to begin taking off the following morning. Soon afterward, the weather soured again as clouds obscured the target area, and Leigh-Mallory, who had flown to Normandy to observe the bombardment, cancelled the mission. The order, however, came too late for several of the leading flights to get the word. Nearly 400 planes dropped 685 tons of explosives. Tragically, a number of the bombs fell short, killing 25 and wounding 131 soldiers of the 30th Division.

Bradley was appalled when he learned that the bombs dropped were considerably heavier than the 100-pound fragmentation types he had requested. The bombers had also approached the rectangle directly over the troops rather than parallel to them. When he inquired of Leigh-Mallory as to the source of the deviations from his understanding of the plan, Bradley was told that the line of flight was changed intentionally. Approaching laterally, said Leigh-Mallory, placed the bombers on a path that was too narrow, forcing them to fly too close together while also exposing them to German antiaircraft fire for a prolonged period.

An hour before the bombers arrived, American troops had pulled out of their positions along the Saint Lô-Periers road as ordered. When the movement was observed by the Germans, Maj. Gen. Fritz Bayerlein, commanding Panzer Lehr, ordered his own troops into the vacated area. As the bombs fell, he expected an attack. However, the fighting that took place was only with Collins’s troops attempting to retake the ground they had given up as a precaution against errant bombs.

Bayerlein was satisfied that he had parried a significant thrust and moved additional troops into the positions the Americans had held, placing them directly in the path of the coming Allied air bombardment, now rescheduled for 11 am the next day, July 25.

Bradley was still stinging from the changes to the air operation that had occurred without his knowledge. Nevertheless, he agreed that the renewed bombardment would be carried out on the terms that Leigh-Mallory specified. The bombers would come in above the American ground troops and enter the rectangle through its broad side. This time, 2,350 heavy bombers, medium bombers, and fighter-bombers were to deliver more than 4,000 tons of bombs.

To minimize the risk of another “friendly-fire” incident, the bombardiers were instructed not to release any bombs until they had cleared the Saint Lô-Periers road. A weather-monitoring aircraft was to be aloft, and if possible the heavy bombers would come in low to sight their targets visually for better accuracy.

The 522 guns of the U.S. VII and VIII Corps along with the four infantry and two armored divisions involved in the ground assault were scheduled to commence a heavy artillery bombardment in support of the Cobra offensive. A total of 170,000 shells were allotted for the barrage.

Flying in groups of 12, the heavy bombers arrived over the target area on the morning of the 25th. The medium bombers then swept in with their high- explosive and fragmentation bombs. The fighter-bombers carried their bombs and a significant amount of napalm, jellied gasoline that burned furiously and clung to any surface with which it came in contact.

Cloud cover once again forced adjustments in bombing altitude. As ordnance fell, clouds of dust spewed skyward and the earth convulsed. Due to difficulties maintaining formation and because the bomber crews had been told to avoid hitting the Saint Lô-Periers road, a number of bombs missed their mark in several directions. One lead aircraft dropped its payload prematurely, and nearly 80 medium and heavy bombers followed suit.

For the second straight day, bombs fell on American soldiers, this time killing 111 and wounding 490. Among those killed was Lt. Gen. Lesley McNair, the commanding general of U.S. Army Ground Forces. McNair had come to the area as an observer and was slated to assume command of the fictitious First U.S. Army Group (FUSAG) to maintain the deception of Operation Fortitude. (General Patton was reassigned to command of the U.S. Third Army, which was to be activated on August 1.)

Bradley wrote, “The ground belched, shook and spewed dirt to the sky. Scores of our troops were hit, their bodies flung from slit trenches. Doughboys were dazed and frightened…. A bomb landed squarely on McNair in a slit trench and threw his body 60 feet and mangled it beyond recognition except for the three stars on his collar.”

The news of McNair’s tragic, unnecessary death was withheld from the media, and he was buried in secrecy to preserve the integrity of Fortitude.

Famed war correspondent Ernie Pyle was with soldiers of the 4th Division when the bombers appeared. He described the scene: “And then the bombs came. They began like the crackle of popcorn and almost instantly swelled into a monstrous fury of noise that seemed surely to destroy all the world ahead of us…. A wall of smoke and dust erected by them grew high in the sky…. The bright day grew slowly dark from it…. Many times I’ve heard bombs whistle or swish or rustle, but never before had I heard bombs rattle. I still don’t know the explanation of it. But it is an awful sound. We dived. Some got into a dugout. Others made foxholes and ditches…. There is no description of the sound and fury of those bombs except to say it was chaos, and a waiting for darkness.”

Bayerlein and Panzer Lehr were also stunned by the ferocity of the American bombardment. Bayerlein recalled, “Back and forth the bomb carpets were laid, artillery positions were wiped out, tanks overturned and buried, infantry positions flattened and all roads and tracks destroyed. By midday the entire area resembled a moon landscape, with the bomb craters touching rim to rim…. All signal communications had been cut, and no command was possible. The shock effect on the troops was indescribable. Several of my men went mad and rushed around in the open until they were cut down by splinters. Simultaneously with the storm from the air, innumerable guns of the American artillery poured drumfire into our field positions.”

Panzer Lehr sustained more than 1,000 dead, wounded, or incapacitated by the bombing, roughly one-third of the troops manning the main defense line or positioned nearby. Only about a dozen tanks and tank destroyers remained operational, and three of Bayerlein’s forward command posts were obliterated. A parachute regiment attached to the division was killed or wounded to a man.

Although a regiment of the 9th Division and a battalion of the 30th Division were still busy digging out casualties from the errant bombs, the three spearhead divisions of VII Corps moved forward promptly at 11 am and initial progress was good. An assault battalion of the 330th Infantry Regiment that had been detached from the 83rd Division for Cobra advanced 800 yards in 40 minutes. Then the Germans who survived the crippling air assault shook off their malaise and manned their weapons. The American advance was slowed by a surprising volume of enemy fire, and, just as in earlier operations, the presence of bomb craters that made the ground difficult to negotiate.

The immediate objectives of the Cobra penetration were the towns of Marigny and St. Gilles, about three miles beyond the shattered German lines. Pockets of resistance held up the Americans’ progress, and on the right of VII Corps the 330th Regiment was halted several hundred yards from its initial objective, an intersection along the Saint Lô-Periers road. Troops of the 9th Division came up short of most of their early objectives after advancing beyond the saturation bombing zone and failed to reach Marigny.

In the center, two battalions of the 8th Infantry Regiment, 4th Division drove along a 2,000-yard front. One of these advanced a mile and a half. The second ran straight into a well-defended German position in an orchard. It took two hours for 18 tanks that had temporarily lost contact with the infantry to come up and blast the Germans from among the apple trees. Seven hundred yards south of the Saint Lô-Periers road, two German tanks with infantry support had dug in along a sunken lane. The panzers were knocked out with bazooka fire, and the 8th Infantry battalion executed a double envelopment of the enemy position. Once again, however, it took tanks to blast the way clear so that the Americans could change direction and reach the edge of the village of la Chapelle-en-Juger.

The 30th Division was tasked with opening the road to St. Gilles for the armored thrust that was to come soon and to take control of crossing points along the Vire River. On the left, troops of the 30th Division jumped off but were soon forced to take cover when they were once again struck by friendly fire from the fighter-bombers. Then, as they crossed the Saint Lô-Periers road, the troops ran into a trio of Panther tanks and supporting infantry. Three Sherman tanks fell victim to the Panthers, and a double envelopment by the infantrymen uncovered more German strongpoints. Finally, a coordinated effort by the Americans succeeded in knocking out a dozen German tanks and armored vehicles.

Another 30th Division objective was the capture of the town of Hébécrevon, but the going was slow as the Americans were obliged to cross streams, and landmines prevented tanks from using the roads. It was midnight before soldiers of the 119th Infantry Regiment were guiding their supporting tanks through the town’s streets and around bomb craters in the pitch-black darkness.

Although the ground attack on July 25 had advanced beyond the Saint Lô-Periers road, there was a general mood of disappointment among American commanders. The bombing seemed at best to have disrupted the German defenses in only a portion of the target area, and the penetration of the enemy defenses had roughly been about two miles—considerably short of expectations. Eisenhower promised never to use heavy bombers again in direct support of ground troops.

In his postwar memoir Crusade in Europe, Eisenhower recalled that Operation Cobra was launched seven weeks after D-Day from a line that the Allies had expected to gain by D-Day+5. He seemed to share the doubts that other senior commanders expressed—that Cobra was destined to become another Goodwood. Bradley, however, refused to take counsel of his own doubts.

Eisenhower wrote of Cobra, “Progress on the first day was slow, but that evening General Bradley observed to me that it was always slow going in the early phases of such an attack and expressed the conviction that the next day and thereafter would witness extraordinary advances by our forces. The event proved him to be completely correct.”

On the evening of July 25, the Americans simply could not comprehend the fact that, after a hard day of fighting, the Germans were on the verge of collapse. Their defensive line from Lessay to Saint Lô had been breached in seven locations. Hausser and Choltitz committed reserves to stop the American advances, but neither realized that Panzer Lehr had been so badly mauled and that Hébécrevon had fallen to the 30th Division. Meanwhile, a renewed attack by the Canadians south of Caen diverted the attention of Kluge, who maintained for a time that the strongest attack was yet to come and would be launched by Montgomery.

On the morning of July 26, the American infantry divisions were still struggling toward their objectives of the first day, but Collins gambled and ordered the armored columns to advance anyway. The task of clearing roads of their own troops and of the Germans to the extent of their penetrations added to the tactical burdens of Maj. Gens. Manton Eddy of the 9th Division and Leland Hobbs of the 30th Division.

The motorized 1st Infantry Division and Combat Command B of the 3rd Armored Division, under Maj. Gen. Clarence Huebner, attacked toward Marigny but were unsuccessful in wresting high ground around the town from the Germans that afternoon. Marigny was not in American hands until the morning of July 27. To the east, the situation developed solidly in the Americans’ favor. Early on the 26th, the 2nd Armored Division, under Maj. Gen. Edward Brooks, headed toward St. Gilles.

Although his original mission was to guard the southern flank of the Cobra offensive, Brooks was determined to advance. With Colonel Charles Lanham’s 22nd Infantry Regiment attached, Combat Command A (CCA) of the 2nd Armored, led by Brig. Gen. Maurice Rose, spearheaded the drive, passing through the 30th Division and crossing the Saint Lô-Periers road, where a Sherman tank was blown up by antitank fire. Undeterred, Rose pressed ahead and encountered only sporadic resistance.

Shortly after noon, fighter-bombers destroyed four PzKpfw IV tanks and a tank destroyer that had held up the CCA column for a short time, and within a few hours the Americans had taken St. Gilles. While the infantry of the 30th Division cleared pockets of resistance, Rose pressed ahead along the St. Gilles-Canisy road. Panzer Lehr had been responsible for the defense of the road, and its virtual destruction during the bombing left the route uncontested. Combat Command A did not encounter appreciable resistance until it reached the town of Canisy. Tactical air support once again helped to clear the way.

The advance of CCA continued through the night. Finally, Rose ordered a halt about 2 am on the 27th along a road junction north of le Mesnil-Herman. Combat Command A had lost fewer than 200 men, three Sherman tanks, and two trucks. At the end of Rose’s run, there was no doubt that the German front had been significantly penetrated.

All day on the 27th, elements of the 2nd Armored Division fought to extend their protective positions on the eastern flank of the Cobra advance route, while the 1st Division and CCB of the 3rd Armored Division continued their struggle to clear Marigny and the surrounding high ground to open the way for the main thrust of the Cobra exploitation phase: the capture of Coutances.

The fall of Coutances would trap thousands of German soldiers between VII and VIII Corps, which were already exerting pressure southward. The Germans had reacted to the threat of encirclement, falling back with a defensive line facing eastward and consisting of elements of the 2nd SS Panzer Division, 353rd Infantry Division, 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division, and a handful of paratroopers still fighting as infantry. Unable to capture Coutances on the 27th and cut off the German withdrawal, the 1st Division was obliged to turn south and take up the role earlier played by VIII Corps, exerting pressure on the Germans south of the road from Coutances to Saint Lô.

Despite some concerns about the lingering German defense of Coutances, it became apparent to Bradley on the evening of July 27 that a significant breakthrough had been achieved. Rather than slowing down to consolidate his gains, Bradley decided to maintain Cobra’s offensive momentum. “Things look really good,” he informed Eisenhower. Bradley ordered his corps commanders to allow the enemy “no time to regroup and reorganize his forces” and to “maintain unrelenting pressure” on the Germans.

Bradley ordered General Corlett and XIX Corps to attack aggressively west of the River Vire and take the high ground between Avranches and Falaise, denying the Germans its use in the event they intended to establish a new defensive line against the growing threat of the encirclement of the Seventh Army in Normandy. Montgomery’s forces around Caen continued their attacks in support of Cobra.

Significantly, with Third Army set to become operational on August 1 and VIII Corps being reassigned to it, Bradley gave Patton control of the corps ahead of schedule. On July 28, Patton sent the 4th and 6th Armored Divisions through the Cobra breach and Coutances fell to the troops and tanks of the 4th Armored late that day. Most German units were in headlong retreat, and operational integrity was disintegrating. The only appreciable resistance in Coutances was offered by a rearguard detachment and petered out by evening.

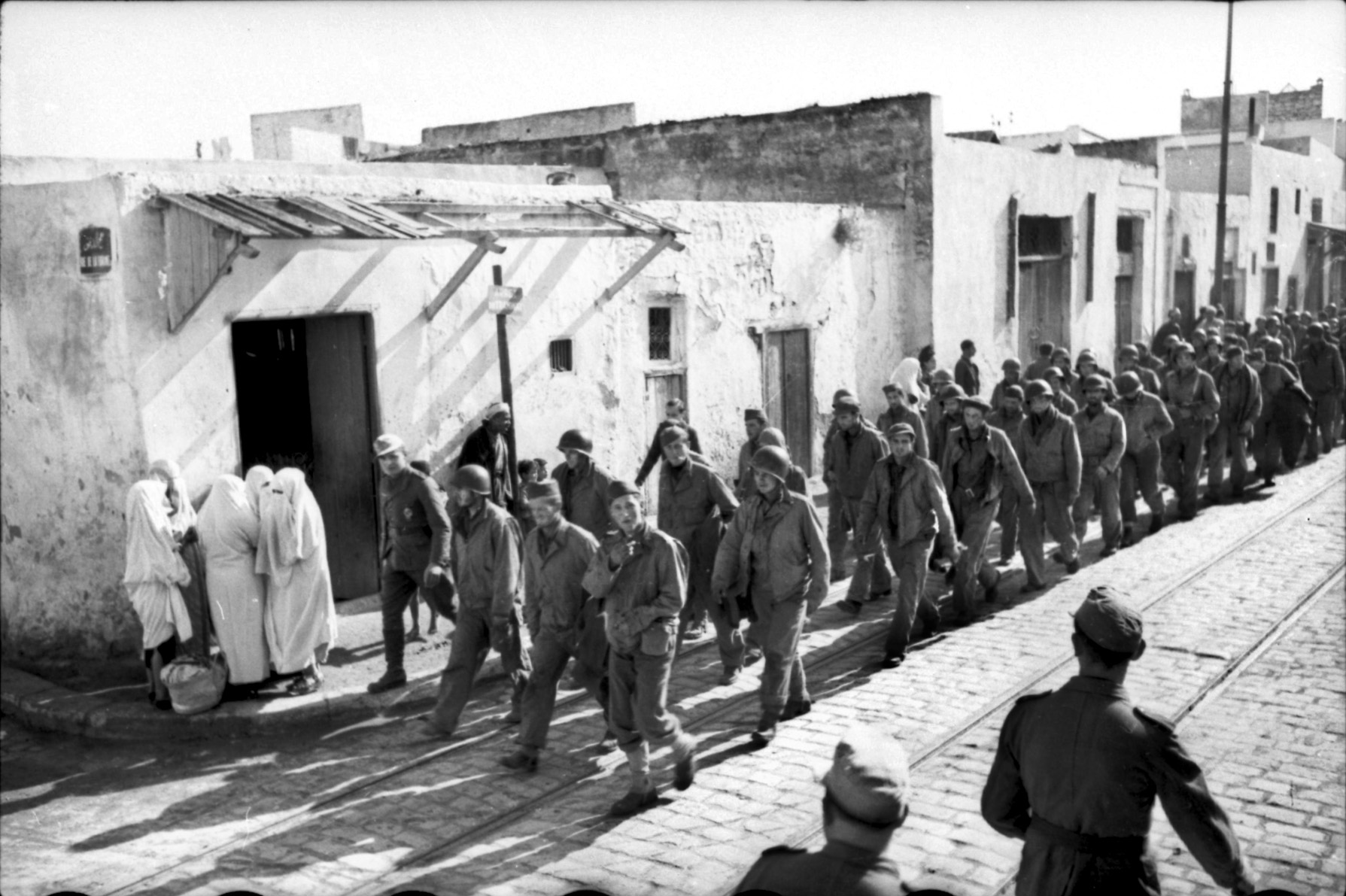

With hardly a pause, Patton worked with Middleton to get the 4th and 6th Armored Divisions farther south, toward Avranches, the gateway to Brittany. Middleton believed that only light resistance stood in his way, and German soldiers were beginning to surrender in large numbers. The capture of Avranches and crossings over the River See would open Brittany to the Allied advance, finally freeing Bradley’s forces from the constricting hedgerow country.

Both armored divisions sped southward. At Bréhal, about 16 miles north of Avranches, Combat Command B of the 6th Armored Division encountered a log roadblock that was blasted by a flight of four fighter-bombers. Eventually, the lead Sherman tank rammed the barricade, and the column resumed its advance. By the evening of the 29th, the 6th Armored had advanced 12 miles and lost two killed and 10 wounded.

In the 4th Armored sector, combat engineers bridged the River Sienne, and the division’s Combat Command B crossed in two columns. One column ran into stiff German resistance on the afternoon of July 30, losing eight half-tracks, suffering 43 casualties, and destroying two German tanks before halting.

To the west, the other column pressed ever closer to Avranches. About 31/2 miles north of the town, the Americans passed within a few hundred yards of the Seventh Army command post, and General Hausser barely eluded capture. As daylight faded, the western column found a pair of bridges intact across the River See and entered Avraches, which was undefended.

When Middleton confirmed that Avranches had been taken, he acted swiftly, ordering reinforcements forward to seize bridges across the River Sélune near the town of Pontaubault, four miles farther south. Possession of these bridges would allow any American force exploiting the breakthrough to move rapidly into Brittany. With that task completed, the VIII Corps had sustained fewer than 700 casualties from July 28-31, while capturing more than 7,000 prisoners. The 4th Armored Division had advanced 25 miles in 36 hours.

On the morning of July 31, Kluge knew the game in Normandy was over. “It’s a madhouse here,” he told General Günther Blumentritt, chief of staff of the German high command in the West. It was “Riesensaurei,” or simply one hell of a mess. “You can’t imagine what it’s like,” Kluge continued. “Commanders are completely out of contact.”

Blumentritt responded that headquarters wanted a detailed description of the new defenses being prepared in Normandy. “All you can do is laugh out loud,” Kluge responded. “Don’t they read our dispatches? Haven’t they been oriented? They must be living on the moon. Someone has to tell the Führer that if the Americans get through at Avranches they will be out of the woods, and they will be able to do what they want. It’s a crazy situation.”

Since Bradley had chosen to watch Cobra develop and respond accordingly, it is reasonable to conclude that the deployment of an appropriate force to exploit the breakthrough into a breakout would be determined by the relative success of the operation. Twenty thousand Germans had been taken prisoner during the six days of Operation Cobra. The German Seventh Army was a shambles, and the German left flank had collapsed.

Finally, on August 1, Patton’s Third Army was officially activated. In accordance with a previously agreed command reorganization, Bradley became the commander of the U.S. 12th Army Group, and Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges took command of the U.S. First Army. Montgomery retained control of the British and Canadian forces of 21st Army Group, now attempting to push southward toward Falaise.

Seeing the tremendous opportunity that had suddenly arisen, Bradley confirmed to Patton that Third Army was to roll through Brittany to Renne in the southwest and through Fougéres in the southeast. To the west, Third Army was to take the Breton ports, including Brest, Lorient, and St. Nazaire. When the word was passed, Patton’s command rode hell for leather.

VIII Corps sped 200 miles to the west and reached Brest in less than a week. In eight days, Patton had taken Le Mans, almost halfway to Paris. By August 18, in a sweeping turn to the northeast, his spearheads had captured Chartres, just 20 miles from the River Seine. A week later, Third Army units had bypassed Paris and crossed the Seine. At the end of the month, Patton was at Verdun, less than 200 miles from the German frontier.

Halted only by a dwindling supply of gasoline, Third Army’s stunning dash across France had covered 400 miles, liberated 50,000 square miles of territory, and bagged thousands of German prisoners. By the time the fuel began to flow again in early September, the Germans had taken advantage of precious time and patched together stronger defenses.

Meanwhile, in late August Allied tactical air power and the troops of the U.S. First Army, the British Second Army, and the Canadian First Army had pressed the remnants of the German Seventh and Fifth Panzer Armies into a small pocket. In an immense slaughter at Falaise and Argentan, more than 10,000 Germans were killed and another 50,000 captured, while over 200 tanks were destroyed. The battle in Normandy was over.

Hard fighting lay ahead; however, weeks of Allied frustration were erased. The defeat of Nazi Germany had become inevitable. Operation Cobra, Bradley’s bold stroke, proved to be the pivotal command decision of World War II in Western Europe.

That is a 60mm M2 mortar being fired in the hedgerows, not an 81mm!