By Chuck Lyons

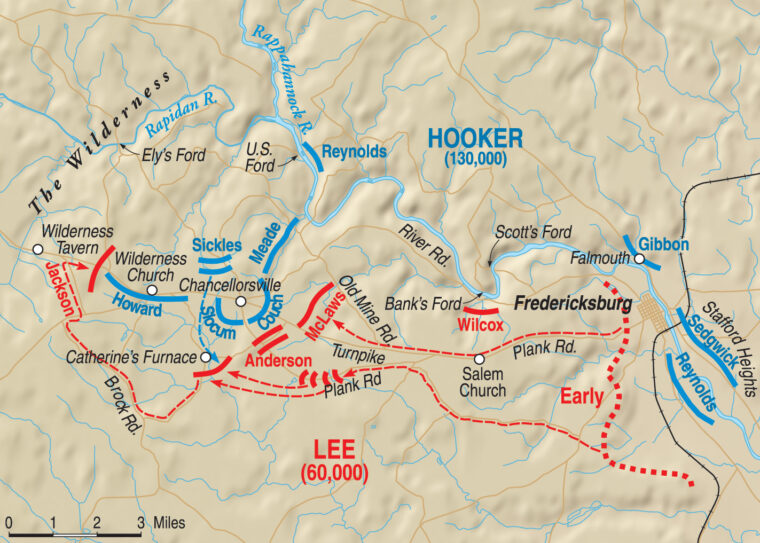

The two Union generals faced each other on the afternoon of May 1, 1863, at the large house by the Orange Turnpike that had been chosen as the headquarters of the Army of the Potomac. The balding corps commander was agitated, and he was seeking an explanation from the army’s commanding general. A short distance to the east, the two opposing armies—Union and Confederate—had begun taking measure of each other that morning, exchanging volleys of musket fire. Not long after the engagement had gotten underway, the corps commander who stood before the army commander had received the following order by courier: “Withdraw both divisions to Chancellorsville.” Similar dispatches went to two other corps commanders marching east toward Fredericksburg.

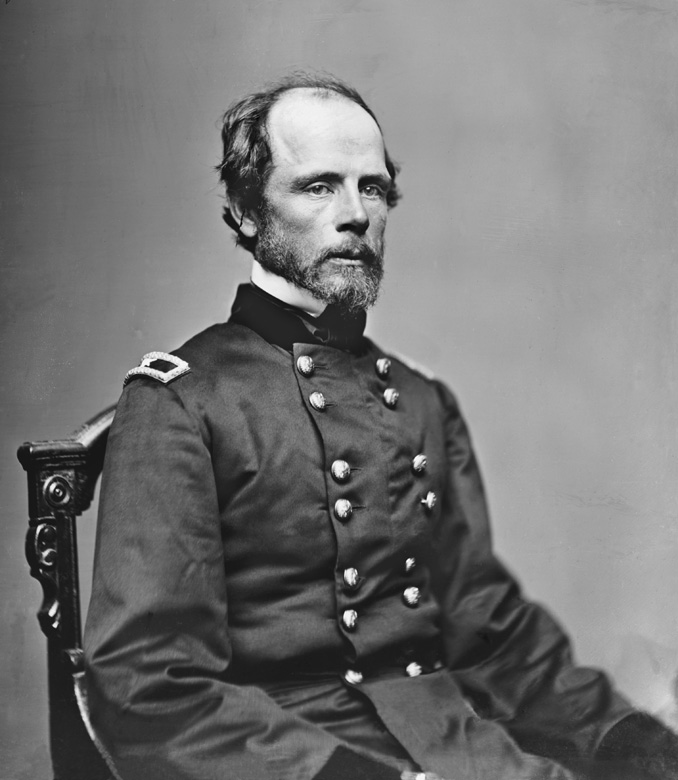

When he received the order, Union II Corps commander Maj. Gen. Darius Couch sent an aide to inform Army of the Potomac commander Maj. Gen. Joseph “Fighting Joe” Hooker that everything was going precisely according to plan. As for the II Corps, it was marching along the Orange Turnpike and, if all went well, might soon be out of the foreboding forested area known as the “Wilderness of Spotsylvania” and onto the high ground south of Banks Ford on the Rappahannock River. Thirty minutes later, Couch received another dispatch reiterating the original order. Couch considered disobeying the order but thought twice about it and broke off his attack. So did Maj. Gen. George Meade’s V Corps to his north on the River Road and Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum’s XII Corps to his south on the Orange Plank Road.

Later that afternoon, Couch had a chance to confront Hooker personally and demand an explanation. “It’s all right, Couch,” said Hooker. “I have got Lee just where I want him; he must fight me on my own ground.”

Couch, the most senior of Hooker’s corps commanders, was deeply skeptical of that assertion. Many years later, Couch wrote, “I retired from his presence with the belief that my commanding general was a whipped man.”

By the morning of May 1, Hooker had managed steal a march on Confederate General Robert E. Lee and get five of his seven corps across the Rappahannock River west of Fredricksburg, outflanking Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

What bothered Couch and his fellow corps commanders was that Hooker was relinquishing the initiative to Lee without even giving them a chance to press their attack. However, Couch had no way of knowing what Hooker knew.

Hooker had envisioned getting much closer to the Confederate main position at Fredricksburg before running into resistance. But Fighting Joe, who had received his nickname accidentally as a result of a newspaper copy room’s typographical error during the Peninsula Campaign of 1862, had received multiple intelligence reports by telegraph that morning indicating that a large body of Confederate troops was marching west to intercept him. Led by hard-hitting Lt. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, the Confederates counterattacked Hooker’s troops, leading Fighting Joe to believe, correctly so, that the two corps already engaged—Couch’s II Corps and Slocum’s XII Corps—were outnumbered by Jackson’s force.

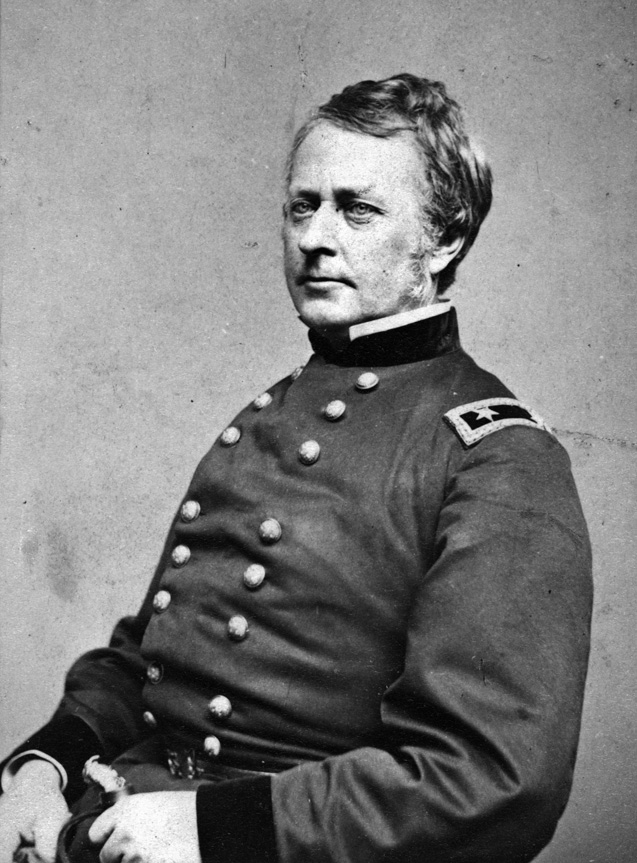

President Abraham Lincoln had advised Hooker at the outset of the campaign to “beware of rashness.” Hooker no doubt reflected on the point after receiving the intelligence reports and ordered his five corps—Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles’s III Corps and Maj. Gen. Oliver Howard’s XI Corps formed the reserve that morning—to entrench and hopefully entice Jackson to hurl his forces against Hooker’s positions the following day. If that occurred, Hooker might do severe damage to Lee’s army after all.

The 44-year-old Hooker was a member of the U.S. Military Academy’s Class of 1837. A veteran of the Seminole Wars and the Mexican War, Hooker resigned from the Army in 1853 but returned as a brigadier general when the war began in April 1861. His performance at the Battle of Williamsburg in May 1862 earned him a promotion to major general, and he led the Union I Corps at the Battle of Antietam and the Center Grand Division at the Battle of Fredericksburg.

Throughout his career, Hooker had carried a reputation as a hard-drinking, hard-living man with a streak of womanizing, a concern for his men, and a proclivity for criticizing his superiors. In 1862, for example, he had criticized Army of the Potomac commander Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan for failing to take the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia, stating, “He is not only not a soldier, but he does not know what soldiership is.”

Hooker had been called intemperate but was praised for liking to fight and for his driving energy. He demanded that his staff be correctly uniformed and well mounted, and he made a grand show of his regular inspections of the army, which inspired his troops.

On January 26, 1863, Lincoln appointed Hooker to replace Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, who had led the Army of the Potomac in the disastrous Battle of Fredricksburg fought December 13, 1862.

After his appointment, Hooker worked diligently to improve the morale of the Army of the Potomac, which numbered approximately 130,000, through changes in the daily diet of the troops, improved sanitation, and the establishment of a fair furlough system.

On April 27, three of Hooker’s seven infantry corps began marching west. To prevent the Confederates from observing troops pulling out of position on the north bank of the Rappahannock opposite Fredericksburg, Hooker issued orders for the three corps farthest from the river—the V, XI, and XII—to move first. All three were to cross the Rappahannock at Kelly’s Ford and then cross the Rapidan River. While Meade’s V Corps crossed at Ely’s Ford, Howard’s XI Corps and Slocum’s XII Corps were to cross farther west at Germanna Ford.

Once across the Rapidan, the three corps were to concentrate at the Chancellor House, located in a clearing on the north side of the Orange Turnpike. Couch’s II Corps joined them on April 30, crossing at U.S. Ford below the confluence of the Rapidan and Rappahannock Rivers. Sickles’s III Corps crossed at U.S. Ford on May 1.

The Orange Turnpike connected Fredricksburg with Orange County Courthouse. Financed during the War of 1812, the turnpike boasted a gravel bed designed to make it passable in all seasons of the year. In 1816, George Chancellor opened a tavern 10 miles west of Fredericksburg on the Orange Turnpike at the its intersection with Ely’s Ford Road. The 21/2-story building was large enough to accommodate overnight guests. When Chancellor passed away in 1836, the tavern declined from neglect. When the war broke out in 1860, members of the Chancellor family still lived there; however, they rented from a new owner.

Lee had approximately 53,000 troops at Fredricksburg. Conspicuously absent was Confederate I Corps commander Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, who with three divisions of his corps was stationed in Southside Virginia to counter Federal seaborne threats to Virginia’s southeastern coast and to prevent the Union Army from raiding inland from its foothold on the coast of North Carolina.

Hooker’s plan called for an attack on Lee at Fredericksburg. The attack would begin with a raid conducted by 10,000 Union cavalry into Lee’s rear to destroy Confederate supply and communication lines between Fredericksburg and Richmond. Hooker believed the cavalry raid would compel Lee to abandon his position at Fredericksburg and fall back toward Richmond. Hooker could then hit the Confederate army as it moved.

Major General George Stoneman’s cavalry assembled upstream for the raid on April 13, but heavy spring rains raised the Rappahannock, forcing Stoneman to wait more than two weeks for the river to drop sufficiently for them to cross.

As for the rest of the Army of the Potomac, part of it would pin down Lee’s army at Fredericksburg, while the other part marched around the Confederate left flank and hit Lee on Marye’s Heights from the rear. After Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia had been defeated, Hooker planned to march south and capture Richmond.

On April 30, Stoneman finally departed on his raid, while three corps of the Army of the Potomac marched upstream, turned south, and massed at Chancellorsville. Meanwhile, Sedgwick’s force established a bridgehead on the south bank of the Rappahannock opposite the Confederate position at Fredericksburg.

Lee was facing what has been called “the gravest situation of his 11-month command” of the Army of Northern Virginia. He could either attack or retreat; he chose the former.

Hooker had reasoned that the Confederate commander, being so badly outnumbered, would have to take his whole force to attack the Union Army behind him at Chancellorsville. In that case, Sedgwick would be ideally placed to close the pincers and trap Lee. If Lee instead chose to attack Sedgwick, the same thing would happen with Hooker closing on Lee from the rear.

Lee realized the real threat was not coming from Sedgwick at Fredricksburg, but from Hooker and his troops at Chancellorsville. He then violated one of the generally accepted principles of war, which is not to divide a force in the face of a superior enemy. Lee took the bulk of his forces to meet Hooker at Chancellorsville, leaving 11,000 men and 56 guns at Fredericksburg under Maj. Gen. Jubal Early.

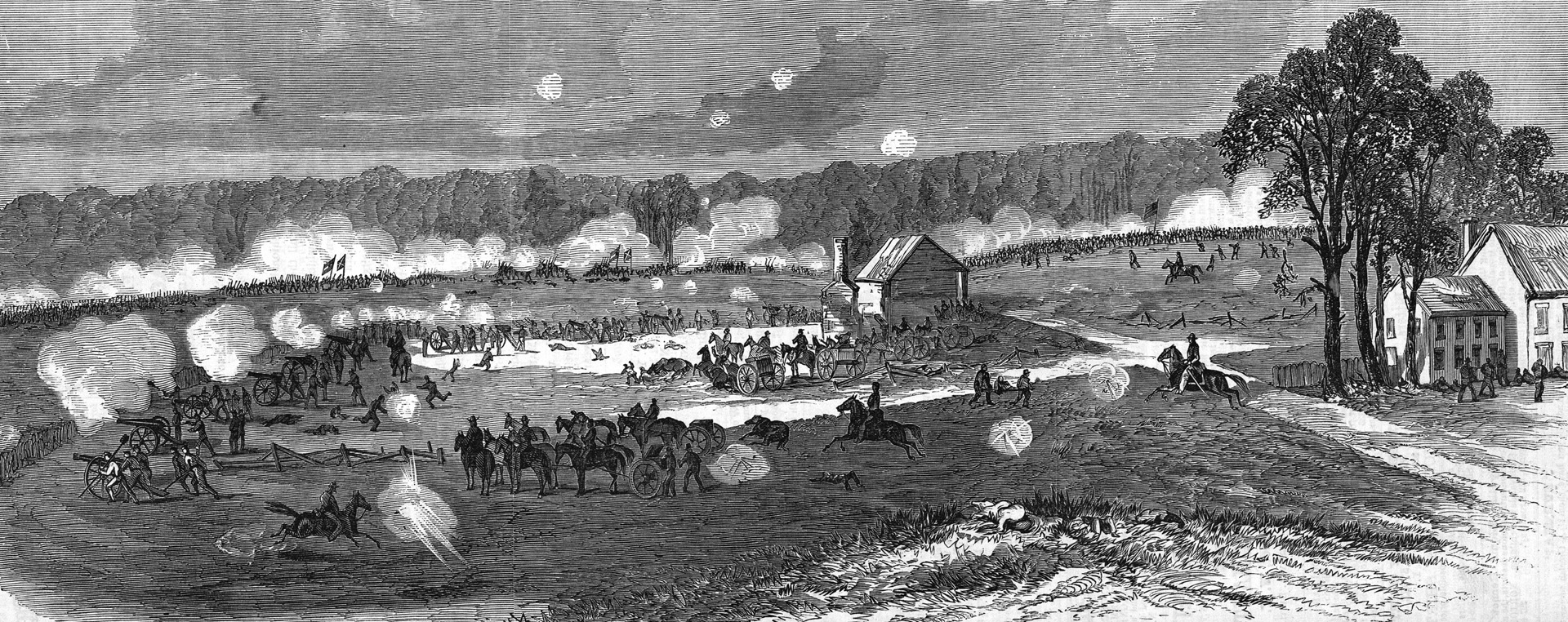

On May 1, Lee sent Jackson’s II Corps toward Chancellorsville. Jackson marched west on the Orange Turnpike and the Orange Plank Road. About the same time, Hooker’s force had begun moving east from Chancellorsville. At 11:20 am, the forces collided about two miles east of Chancellorsville. Jackson continued to push west, driving back Hooker’s troops. Shortly after the fighting started, Jackson was joined by Confederate cavalry commander Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart.

The two forces skirmished until about 2 pm, when Hooker called back the three corps he had sent east on separate roads. Hooker had received incorrect reports that some or all of the detached forces under Longstreet had returned to the area, and Fighting Joe was keenly aware that Lee was not acting as if he were badly outnumbered. Undaunted, Hooker told his aides, “The enemy is in my power, and God Almighty cannot deprive me of them.”

To instill confidence in his decision to entrench, Hooker sent the following message at the end of the day to his subordinates: “The major general commanding trusts that a suspension in the attack today will embolden the enemy to attack him.”

As Hooker drew back that afternoon, the Confederate forces followed, forming a line encircling Chancellorsville, and the day ended with both sides digging in.

That night Lee and Jackson met on the Orange Plank Road to plan the next morning’s action but moved into a group of pine trees as a Union sniper began to fire at them. Sitting together on the same log, they discussed the situation. As they talked, Stuart arrived to report that a cavalry unit commanded by Brig. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee, Robert E. Lee’s nephew, had reported that Hooker’s right flank was in the air. Howard’s XI Corps was camped on the Orange Turnpike without having anchored its flank and therefore was vulnerable to attack, said Stuart. Further investigation during the night uncovered a route around Hooker’s army that would allow Jackson to pass largely without being seen.

Based on Stuart’s report and the later investigation, Lee and Jackson devised an audacious plan.

Lee again divided his forces, agreeing to let Jackson take 28,000 men and march around the Union Army to attack Hooker’s vulnerable right flank. The flank march would take most of a day, and during that time Lee would face five Union corps with approximately 14,000 Confederate infantry in six brigades. Lee also had one and a half regiments of cavalry and six batteries of artillery. It was the greatest gamble of Lee’s career. If Hooker moved against him while Jackson was on his flank march, Lee might face the destruction of his army.

Jackson agreed to march with his entire command and his artillery. He would be screened by Stuart’s cavalry, which would attempt to keep Union troops far enough away that Jackson could pass unseen while Lee’s troops would demonstrate in front of the Union position, giving every indication an attack was being prepared.

At 8 am on May 2, Jackson began his flank march.

Meanwhile, Hooker had inspected his line and was pleased with the fortifications that had been dug during the night. Hooker expected Lee to hit the center of his line and was prepared to inflict heavy casualties on him. When Hooker returned to his camp, he was informed by a courier sent by Sickles that a large Confederate column had been spotted moving south. Union artillery had fired on the column, but the shells had little effect. Sickles then rode to Hazel Grove, a patch of high ground, and made a personal reconnaissance of Jackson’s column.

Hooker misinterpreted the movement as a Confederate retreat, which seemed to him the right thing for Lee to do in the situation. Just to be safe, though, Hooker ordered Howard, whose XI Corps held the right flank, to “advance your pickets for purposes of observation as far as may be safe in order to obtain timely information of [the enemy’s] approach.” Howard replied that he was “taking measures to resist an attack from the west.”

Hooker then sent orders for Sickles to move south from Chancellorsville and “advance cautiously toward the road followed by the enemy, and harass the movement as much as possible.” Sickles sent a division, flanked by two battalions of sharpshooters, south as ordered. By doing do, Sickles left a gap in the Union line east of Howard’s position, isolating Howard and his men even further.

The nearest Union troops to the XI Corps were positioned two miles to the east. The troops Sickles sent against Jackson’s column arrived too late to do much damage. Colonel Emory Best’s 23rd Georgia Infantry, deployed 300 yards north of Catherine Furnace to guard the rear of Jackson’s column, was able to resist Sickles’s strike, but the Georgians were driven south. Sickles’s troops attacked the Georgians in the afternoon, and by 5 pm had pushed them back to the Catherine Furnace. But by that time the rear of Jackson’s column had already passed. Two brigades from Confederate Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill’s division at the back of the column turned to block any possible Union pursuit.

By that time, Hooker believed Lee was in full retreat toward the railroad hub at Gordonsville, and he ordered his corps commanders to prepare to pursue the enemy in the morning.

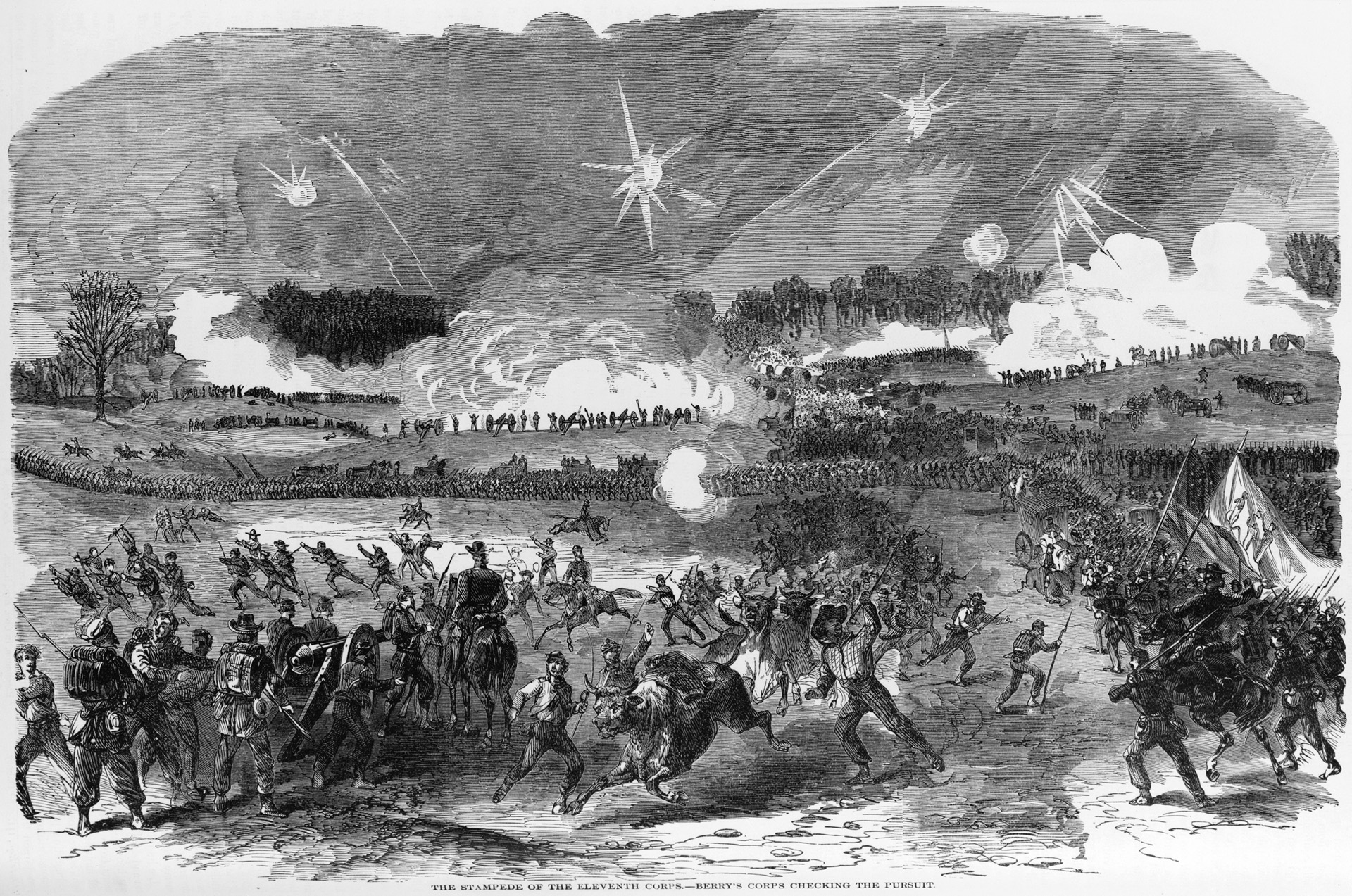

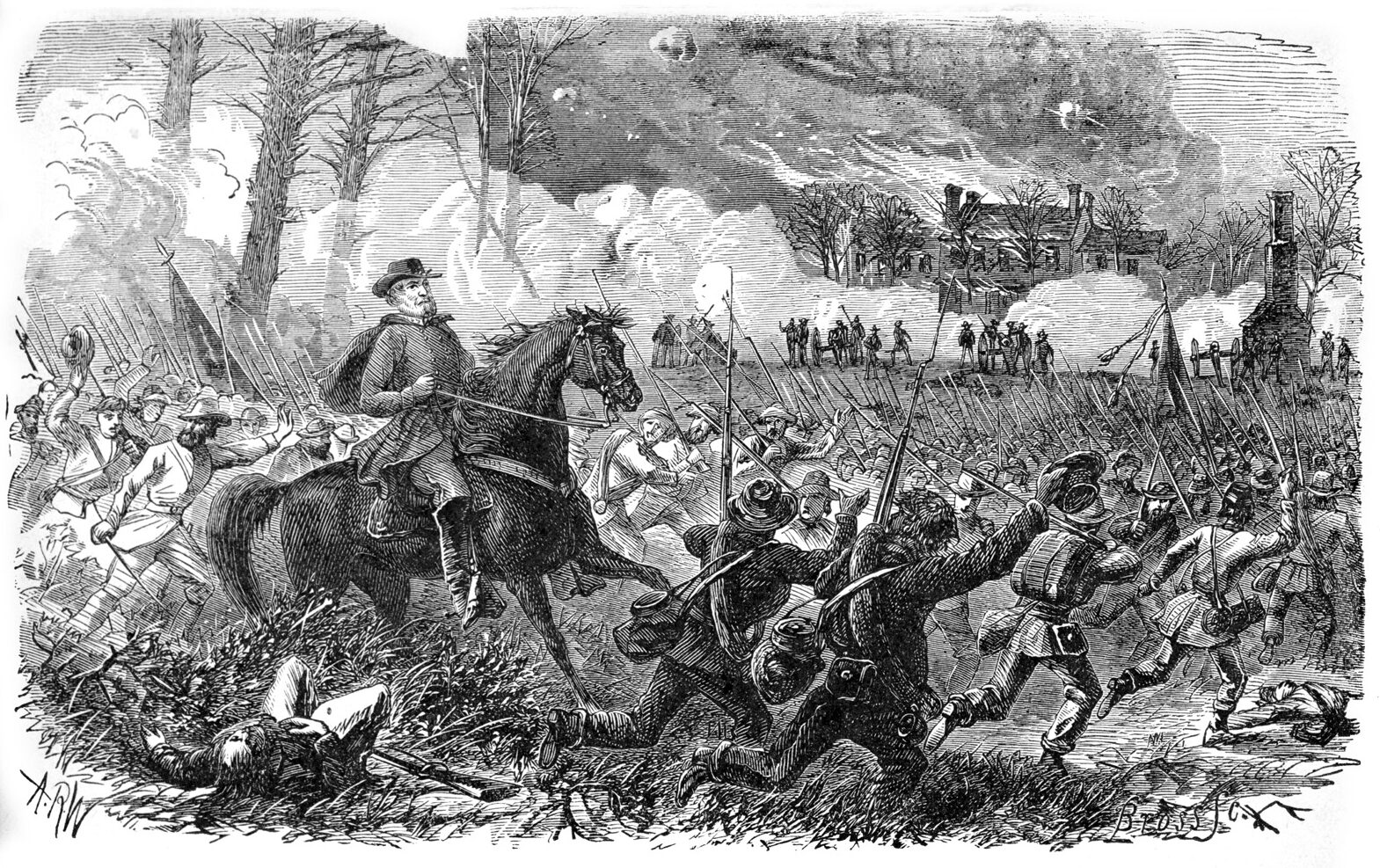

After completing a grueling 14-mile march at 5:30 pm, Jackson formed his men in two lines stretching across the Orange Turnpike. Despite the warning from Hooker and his own claim that he was “taking measures to resist an attack,” Howard had made little preparation or provision for defense. When Jackson’s men attacked, most of Howard’s men, who were suffering from poor morale, were resting. The Union right flank was not anchored by any natural feature, and only two cannons and about 900 men had been deployed facing west toward the woods from which the Confederates would soon emerge.

Before the Confederate attack, Fitzhugh Lee had led Jackson up a hill where the men could view the Union right flank laid out before them. The XI Corps line of battle was a few hundred yards in front of them, and they noted abatis in front of the line, stacked rifles, and two cannons facing west.

“The soldiers were in groups in the rear, laughing, chatting, smoking, probably engaged, here and there, in games of cards and other amusements indulged in while feeling safe and comfortable, awaiting orders,” wrote Fitzhugh Lee.

That quiet scene was soon thrown into upheaval.

Rebel bugles sounded, and Confederates streamed out of the woods across an almost two-mile front. The attackers were screaming the rebel yell and firing their muskets. The 900 bluecoats facing them turned and ran, abandoning their two cannons. They were quickly joined by the remainder of Howard’s troops. With great personal courage, Howard attempted to rally his men, shouting and waving a flag that he held under the stump of his right arm, which he had lost at the Battle of Seven Pines the previous year.

Jackson rode with his men in the attack. “I have never seen him so well pleased with the progress and the results of a fight,” wrote Captain Richard Wilbourn, a member of Jackson’s staff.

Despite Howard’s efforts, his force was quickly routed. Most of the men fled in the direction of U.S. Ford. Before it was over, Howard’s corps, 11,000 strong, had suffered 2,400 casualties.

By nightfall, Jackson’s Confederates were within sight of Chancellorsville, but they were almost as disorganized as the Union men they had routed, preventing further pursuit. As the night lengthened, shooting broke out, subsided, and then broke out in new places. Jackson’s men were separated from Lee only by Sickles’s corps, split from the main body of the Union army by the afternoon’s fighting. Sickles began a loose retreat, mistakenly skirmishing with other Federal units when they collided in the dark near Hazel Grove.

At the Chancellorsville crossroads, Federal artillery fired blindly at any movement in the surrounding woods.

At about 9 pm, Hooker ordered Sedgwick to march toward Chancellorsville to “attack and destroy any force he may fall in with on the road,” a move that indicated Hooker still had hopes of springing his trap despite Jackson’s attack on his right flank.

The fighting on May 2 ended with both sides digging in almost within sight of each other. Throughout the Wilderness, brush fires burned wildly, but exhausted troops on both sides slept soundly. It was “like a picture of Hell,” wrote one cavalryman, observing the eerie scene from a hilltop.

Jackson wanted to press his advantage while he had Hooker on the ropes. Stonewall rode east on the Orange Plank Road after dark, contemplating a night attack by the light of the moon. Such an attack would put Confederate forces on the banks of the Rappahannock and cut off any retreat by Hooker. As Jackson and his staff returned to their camp, they were spotted by men of the 18th North Carolina Infantry, nervous after a recent engagement with Union cavalry. Mistaking Jackson and his staff in the darkness as the same cavalry, they fired at the passing horsemen. Jackson was hit three times, one bullet shattering his left arm. He was quickly taken back to his camp, where the arm was amputated.

Jackson lingered for more than a week before contracting pneumonia. He died on May 10. Lee said, “He has lost his left arm, but I have lost my right.” Stuart was placed in charge of Jackson’s men.

Despite Jackson’s flanking march and successful attack, the Union army was still in the battle. Maj. Gen. John Reynolds’s I Corps arrived during the night of May 2, helping to stabilize the situation. At that point, 42,000 Confederates confronted six Union corps. The two halves of Lee’s army were still separated by Sickles’s III Corps on the high ground at Hazel Grove.

Couch, who from that day forward was a lifelong enemy of the Union commander, said later that all Hooker had to do was “take a reasonable common sense view of the state of things.”

Hooker failed to do that.

Early on the morning of May 3, Hooker ordered Sickles to abandon the high ground at Hazel Grove and move to a new position on the Plank Road, a move intended simply to tidy his lines. However, it would prove a fatal one. Hazel Grove has, in retrospect, been seen as the key to the entire position; Confederate artillery on that high ground could control the field. As it withdrew, the rear of Sickles’s corps was attacked by the Confederate brigade of Brig. Gen. James Archer, which captured four of Sickles’s guns and 100 of his men.

Lee, more open to the possibilities Hazel Grove offered than Hooker was, moved quickly. Lee ordered Colonel Edward Porter Alexander to deploy 30 guns on the high ground at Hazel Grove that Sickles had just abandoned.

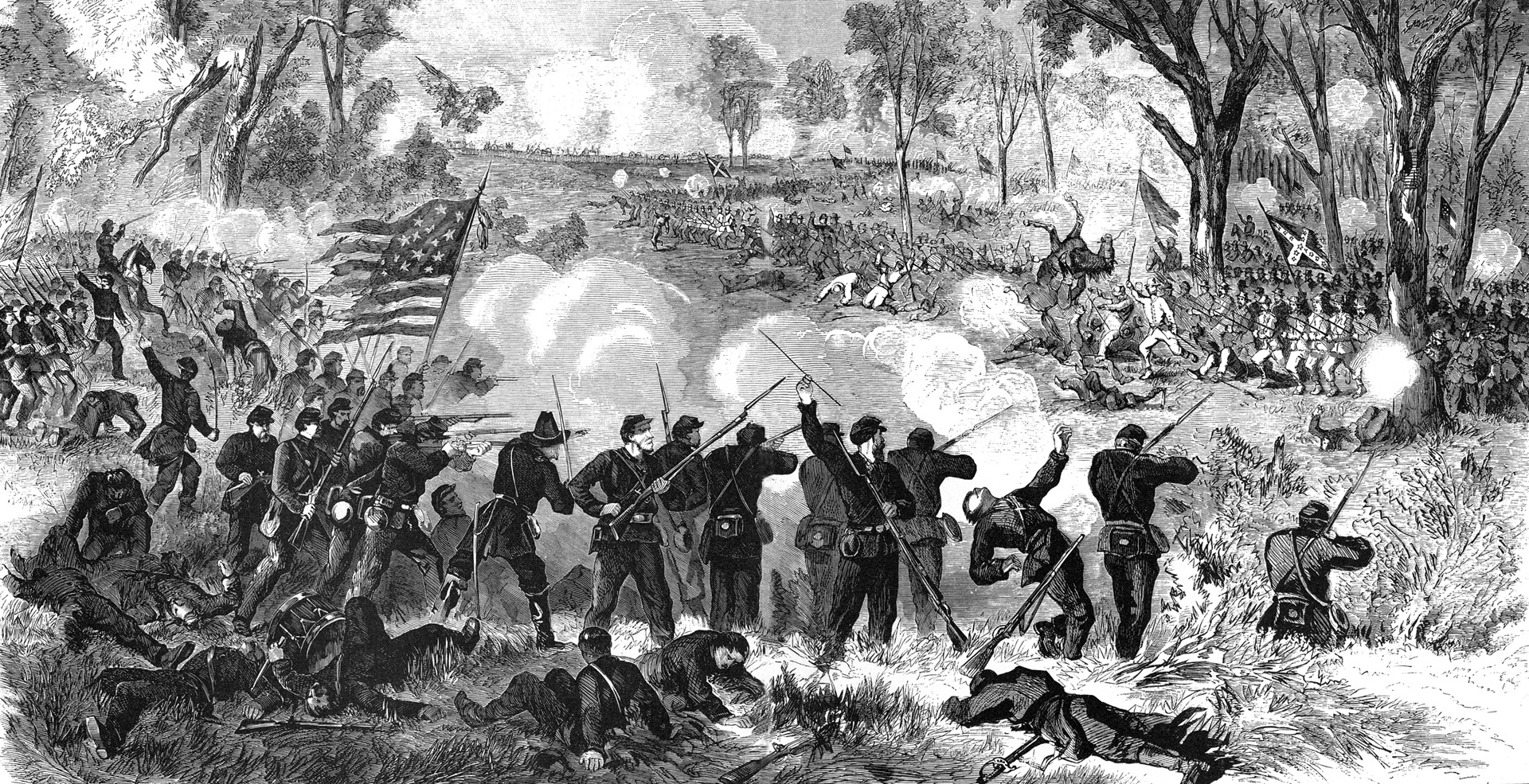

Hooker’s force had by that time been deployed in a giant horseshoe against the Rappahannock, protecting the U.S. Ford and facing south. At about 5:30 am, Lee attacked from the south and southeast. The newly deployed artillery at Hazel Grove supported the attack. Thirty Confederate guns also had been placed near the Chancellor House, and another 24 were on the Orange Plank Road southeast of Hooker’s position. The Union forces were fighting behind strong earthworks, and the initial Confederate assaults were beaten back. A final Confederate push combined with artillery fire carried the day, but the Union defenders began a fighting withdrawal to new positions near the river.

Lee’s army reunited at about 10 am at the Chancellor House, which by then was burning from artillery fire. When Lee approached the house, a staff officer later wrote, he was greeted with “one long, unbroken cheer, in which the feeble cry of those who lay helpless on the earth blended with the strong voices of those who still fought, roaring high above the roar of the battle.”

The Confederate guns at Hazel Grove dueled with the Union guns on Fairview Hill until their ammunition ran low. The exuberance of the Confederate gunners that day was best expressed by Major William Pegram, who fought with Walker’s artillery battalion. “A glorious day, Colonel! A glorious day!” Pegram said to Alexander.

About 9:15 am, before abandoning the Chancellor House, Hooker was leaning against a wooden pillar. A Conferderate cannonball struck the pillar. Hooker wrote later that half of the pillar “violently [struck me] in an erect position from my head to my feet.” Hooker was unconscious for an hour. When he came around he refused to relinquish command. The injury may have contributed to the Union defeat. Several of his subordinates, including Couch and Slocum, later openly questioned Hooker’s command decisions after the injury.

Meanwhile, Sedgwick’s VI Corps had attacked Fredericksburg. By mid-morning, Union forces had twice assaulted the stronghold of Marye’s Height and been repulsed with heavy casualties. A Union party was then allowed to approach the stone wall on the heights sheltering Confederate defenders to collect Union wounded. While doing so, members of the party observed that the Confederate line behind the wall appeared weak. The center was held by only two small regiments and 16 guns. Spurred on by this information, a third Union attack overwhelmed the wall and captured the heights.

Sedgwick then moved west toward Chancellorsville as Early pulled back in a fighting retreat to the south. Lee again divided his force, sending General LaFayette McLaws with 7,000 men to check Sedgwick’s 23,600 troops and keeping 35,000 to confront Hooker’s six infantry corps. But Brig. Gen. Cadmus Wilcox quickly spread his Alabamians across the Orange Plank Road, slowing Sedgwick’s advance and allowing McLaws to move his division to Salem Church, south and west of Fredericksburg, to stop the Union movement. In addition, Union Brig. Gen. John Gibbon’s 3,500-man division of the II Corps, which had been left behind to assist Sedgwick, also crossed the Rappahannock north of Fredericksburg. About 5:30 pm Union forces attacked the church but were repulsed. During the night, Sedgwick heard Confederate columns moving around him in the dark.

On the morning of May 4, Lee ordered Early to join McLaws at Salem Church and sent Maj. Gen. Richard Anderson to the area. Lee then rode over to conduct a personal reconnaissance. He found that Early had retaken Marye’s Heights and that he and McLaws planned to attack Sedgwick as soon as Anderson arrived. However, Anderson did not reach the area until 6 pm. The Confederates launched an attack but accomplished little. Anxious to solidify what already had been gained, Lee, for the first time in his career, ordered a night attack. It was repulsed.

That night, Sedgwick pulled his men back across the river at Banks Ford, a short distance north of Salem Church, and Lee turned his attention back to Hooker. When Hooker learned of Sedgwick’s retreat, he called his corps commanders together to discuss the situation and vote on what should be done. A narrow majority wanted to continue fighting, but Hooker decided to withdraw. During the night, he pulled his forces across the river at U.S. Ford. The troops crossed in heavy rain that had caused the river to rise and threatened to break the pontoon bridges. By 9 am on May 6, the withdrawal was complete.

The Confederate forces, although outnumbered by more than two to one, had routed Hooker’s army. In the process, they had suffered 13,460 casualties: 1,724 dead, 9,233 wounded, and 2,503 missing. Hooker’s casualties at Chancellorsville were 17,304 men; 1,694 were killed, 9,672 wounded, and 5,938 missing.

Despite the loss, which shocked the Northern states, and in the face of criticism from many of his generals, Lincoln retained Hooker in command of the Army of the Potomac. Couch, claiming he was disgusted by Hooker’s conduct of the battle, resigned and spent the rest of the war in command of Pennsylvania militia. Hooker relieved Stoneman for incompetence and for years after the war waged a campaign against Howard, who he blamed for his loss. Hooker wrote that Howard was “a perfect old woman.” Hooker also accused Sedgwick of being “dilatory.”

Before he died, Jackson voiced yet another opinion, blaming Hooker’s defeat on the lack of Union cavalry. “That was his great blunder,” Jackson told an aide. “It was that which enabled me to turn him, without his being aware of it, and take him in the rear.”

Meanwhile, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia began marching north in June. Lee was convinced by the performance of the Union Army at Chancellorsville that his troops were superior to those of the enemy and would prevail in the next major battle. Hooker, who had planned on attacking Richmond, was ordered by Lincoln to pursue Lee while also keeping an eye on the defense of Washington and Baltimore. On June 28, just three days before the Battle of Gettysburg, Lincoln replaced Hooker with Meade.

Hooker became commander of the XI and XII Corps of the Army of the Potomac and was sent west with those troops to reinforce Maj. Gen. George Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland at Chattanooga, Tennessee. In November 1863, Hooker led his troops well in the Battle of Lookout Mountain and the Battle of Missionary Ridge, regaining some of his former reputation as a solid battlefield commander. Hooker then led the XX Corps in the 1864 Atlanta Campaign, but he resigned before the capture of Atlanta when Howard was promoted to command of the Army of the Tennessee.

Hooker subsequently was named commander of the Northern Department, which comprised Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, and he served in that position until the end of the war.

Lee later told John Bell Hood, who at the time of Chancellorsville was a major general commanding a division under Longstreet at Southside Virginia, “Had I had the whole army with me, General Hooker would have been demolished.”

Hooker had devised a fine plan at Chancellorsville, but Lee and Jackson had devised a better one in response.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments