By William E. Welsh

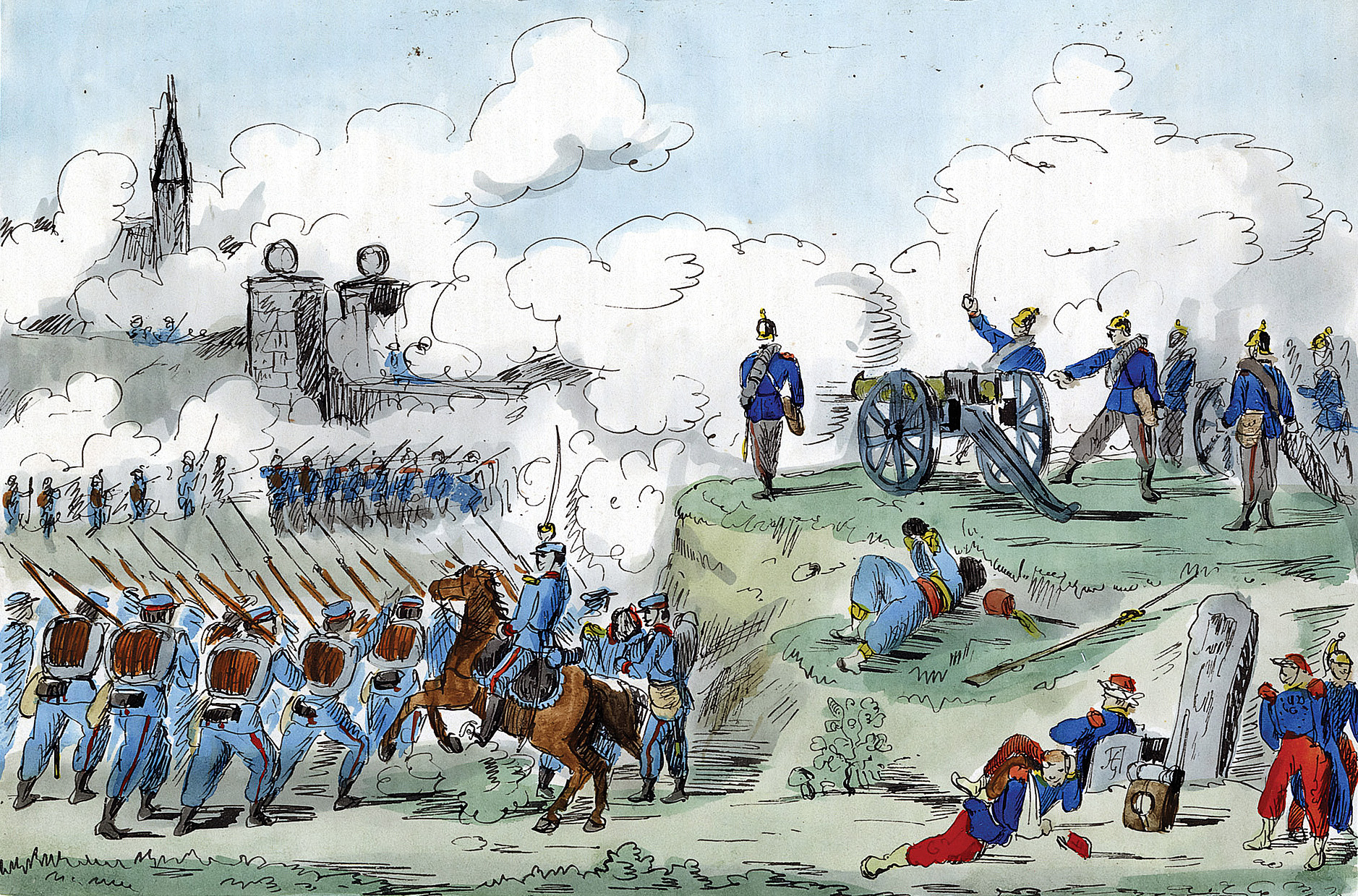

King William I of Prussia stood resplendent in the uniform of a Prussian Guard officer on a hill in eastern France on a sunny day in late summer 1870. The 73-year-old monarch watched with pride as a seemingly endless sea of troops clad in dark blue uniforms marched past him headed east toward enemy positions on a ridge near Metz. With the Prussian king that morning were Minister President Otto von Bismarck, Chief of Staff Helmut von Moltke, and Second Army Commander Prince Frederick Charles.

Those assembled on the hill could hear to their north the steady boom of the Krupp cannons that had bedeviled the French Army of the Rhine since the war began one month earlier. Soon another mass of Prussian artillery much closer began a thunderous barrage of the French positions to the east. A total of 200,000 troops from two Prussian armies were on the move that morning. By noon some units were ready to attack, but most were still marching to their designated positions.

Moltke’s plan to envelop the French, which had been frustrated at the border, seemed at that moment to be bearing fruit. Prince Frederick Charles’ Second Army had stolen multiple marches on the French Army of the Rhine since the frontier battles at Froschwiller-Worth and Spicheren on August 6. While the 112,000-strong French army resupplied itself at Metz, Prince Frederick Charles marched south of Metz and then swung north to cut the French army’s route of retreat to Verdun and communications with Paris.

Moltke’s plan for the day was for the Prussian First Army, led by General Karl von Steinmetz, to feint at the French left while the Prussian Second Army enveloped the French right flank. Moltke believed this would force the French to fall back to Metz where they would be trapped and eventually compelled to surrender. First, however, the Prussians had to drive the French from an excellent defensive position. The French held the high ground, and they had spent the previous day entrenching. Most of the French units would have a clear field of fire against the Prussians.

From time to time a messenger rode up and delivered a report to the king. William I was calm as the chaos of battle swirled around him, but his chief of staff was deeply agitated. Moltke rose frequently from his seat on a pile of knapsacks to stride about with his hands joined behind his back and his head bowed in thought.

Also observing the battle from that vicinity was New York World correspondent Moncure Conway, whose account of the action captured the fury of the battle once the Prussian infantry advanced.

Also observing the battle from that vicinity was New York World correspondent Moncure Conway, whose account of the action captured the fury of the battle once the Prussian infantry advanced.

“From their commanding eminence, the French held their enemies beneath them, and subjected them to a raking fire,” wrote Conway. “Their artillery was stationed far up by the Metz road, between its trees. There was not an instant’s cessation in the roar; and easily distinguishable amid all was the curious grunting roll of the mitrailleuse. The Prussian artillery was to the north and south of [Gravelotte], the mouths of the guns on the latter side being raised for an awkward upward fire. The French stood their ground and died—the Prussians moved ever forward and died, both by hundreds; I almost said thousands … so fearful was the slaughter.”

Like the road to Metz, the road to war had been a short one. Four years earlier, Prussia had defeated Austria in just seven weeks. Through the Peace of Prague, Prussia eliminated the Austrian-led German Confederation and replaced it with a Prussian-led North German Confederation. But this still left the South German States outside Prussia’s control. Bismarck saw a war with France as a way to finish the goal of uniting all German states in a Prussian-led German empire. But it meant waiting for the right opportunity.

That opportunity came in the form of the Ems Dispatch in which Bismarck framed King William’s conversation on July 13 to the French ambassador to Berlin on a highly sensitive matter in such a way as to make it seem an affront to the ambassador. Spain had offered its throne to Prince Leopold Hohenzollern, a cousin of the Prussian king, who had declined the offer, and the French wanted assurances that he would not accept it at a later date. William had already told the French that Leopold would not accept the offer; the Prussian king did not want to discuss the matter again. The French had played right into Bismarck’s hands. On July 19, 1870, French Emperor Napoleon III, or Louis-Napoleon, declared war on Prussia.

In the nearly two decades that he had been in power, Louis-Napoleon had invested in new weapons that would give his troops an edge over their adversaries. The most effective of these was the breech-loading Chassepot rifle, which by virtue of a better seal on the breech, had twice the range of Prussia’s breech-loading Dreyse rifle. Another new weapon was the mitrailleuse, a primitive precursor to the machine gun. The mitrailleuse, mounted like a cannon on a carriage, could fire up to five 25-round bursts in one minute. But the mitrailleuse lacked many of the best features of the 20th-century machine gun, such as automatic loading and easy traversing. Moreover, the French deployed it with the artillery instead of assigning it to infantry units as close-fire support.

As for the Prussians, their major technological advantage was breech-loading artillery. The Krupp-made guns were superior to the French muzzle-loading artillery in range, accuracy, and rate of fire. The Prussians also switched to a percussion fuse, which was far more reliable than the powder fuse used by the French.

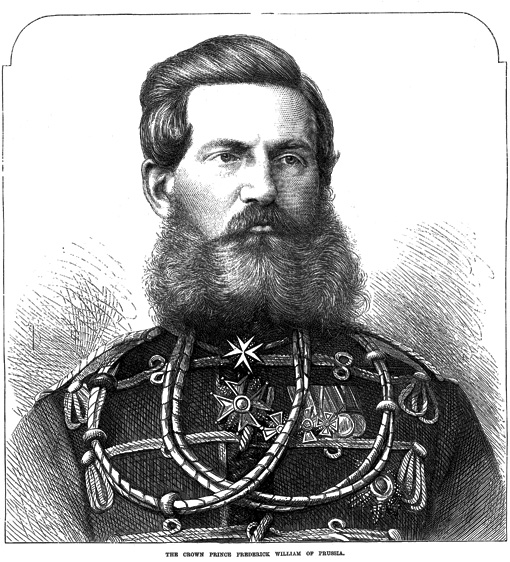

By the end of July, the Prussians had deployed 310,000 men in 14 corps on the French border. Steinmetz’s First Army, numbering 50,000 men in three corps, was deployed in the Rhine Provinces. The other two armies were deployed in the Palatinate. Frederick Charles’s 135,000-strong Second Army, organized into six corps, was deployed in the western Palatinate near Saarbrucken. Crown Prince Frederick William’s 125,000-strong Third Army, divided into five corps, was stationed in the eastern Palatinate opposite northern Alsace.

In contrast, the French had about 225,000 men in eight corps. Napoleon III had deployed his eight corps at intervals on the border. The dispersed deployment would make it hard for one corps to reinforce another in the coming campaign.

Moltke’s strategy for invading France was that Steinmetz and Crown Prince Frederick William would attack and defeat the French in front of them on the flanks first. Then they would envelop the French forces between them in the center opposite Saarbrucken. But Steinmetz completely ignored the strategy. Rather than crossing the Saar River at Merzig to attack the French forces in front of him, he diverted toward Saarbrucken when he learned that General Charles Frossard’s II Corps had on August 2 occupied the lightly held German city.

Unlike Steinmetz, Crown Prince Frederick William followed his orders correctly. On August 4, the Prussian Third Army invaded northern Alsace. General Abel Douay’s division of Marshal Patrice MacMahon’s French I Corps at Wissembourg was not expecting a Prussian attack so quickly after a declaration of war and was defeated in a six-hour battle against three German corps.

Alerted that a large Prussian force was at Wissembourg, the following day MacMahon deployed his entire 48,000-strong corps in a line on a forested ridge 17 kilometers south of Wissembourg at Froschwiller-Worth and awaited the inevitable Prussian attack. In the battle that unfolded on August 6, MacMahon’s five divisions were no match for the crown prince’s nine divisions backed by 150 guns. The battle, which Prince Frederick William had not ordered, was brought on by overly aggressive Prussian corps and division commanders eager to test their troops against the French. The Battle of Froschwiller-Worth cost the Prussians 10,500 casualties. As for French, they lost 6,000 killed and wounded and 9,000 captured.

To the west, Frossard withdrew from Saarbrucken on August 5 when he learned that two Prussian armies were converging on the city. Frossard took up a new position three kilometers to the south on a ridge near Spicheren to await the Prussians. The vanguards of the Prussian First and Second Armies followed closely on Frossard’s heels. On August 6, the Prussians launched frontal attacks first against the French right and then against the French left. Neither attack pierced the French line of battle. But when the Prussians launched a successful flank attack against the French left late in the day, Frossard ordered a retreat. At the Battle of Spicheren, the Prussians paid a high price for their ineffective frontal assaults, losing 5,000 men. French losses included 2,000 killed and wounded and 2,000 captured.

On August 7, Napoleon III organized his eight corps into two armies. The five French corps in western Lorraine (II, III, IV, VI, and the Imperial Guard), which were the cream of the French army, became the Army of the Rhine under his direct command. As for the remaining three corps (I, V, and VII), the French emperor organized them into the Army of Chalons with MacMahon as its commander. Napoleon III ordered MacMahon to retreat to Chalons. The French emperor intended to retreat with the Army of the Rhine first to Metz to get much needed supplies before continuing to Chalons.

By August 9, the French Army of the Rhine had assembled behind the Nied River 15 kilometers east of Metz. On August 12, Prussian cavalry seized the Moselle River crossing at Pont-a-Mousson south of Metz. That same day, Louis-Napoleon informed Marshal François-Achille Bazaine, the most senior French corps commander, that his declining health made it imperative that he transfer command of the Army of the Rhine to Bazaine. Napoleon III told Bazaine he would soon depart for Chalons, even though the French emperor lingered at Metz for three more days saying goodbye to his troops.

As soon as Pont-a-Mousson was in Prussian hands, Moltke ordered all three Prussian armies to cross the Moselle south of Metz and then swing north to block Bazaine’s retreat. Steinmetz once again disobeyed Moltke’s orders. Instead of bypassing Metz, Steinmetz advanced directly toward the city. Although Steinmetz’s repeated disregard for orders was sufficient grounds for removal, Moltke was reluctant to take such action because Steinmetz was a longtime personal friend of the Prussian king.

On August 14, Bazaine’s army was passing through Metz to new bivouacs on the west side of the city when one of Steinmetz’s divisional commanders launched an unauthorized attack against General Claude Decaen’s III Corps encamped east of the city. The Battle of Borny was a French tactical victory but a strategic defeat in that it further delayed Bazaine’s march west. Decaen was killed during the battle, and Bazaine appointed General Edmond Leboeuf to succeed him. The Prussians lost 4,600 men in the rearguard action compared to French losses of 3,900 men.

The direct route to Chalons from Metz passed through Verdun. To make it from Metz to Verdun, Bazaine needed to march his army west on the Vionville Road through a string of villages—Graveolotte, Rezonville, Vionville, and Mars-la-Tour. An alternate route, the Doncourt Road, passed through Doncourt to Verdun. A third route, the Briey Road, farther north and more circuitous, passed through the villages of Saint-Privat and Briey.

At 10 am on August 15, Bazaine ordered the II and VI Corps to march to Verdun on the Vionville Road, and the III and IV Corps to do the same on the Doncourt Road. Prince Frederick Charles assumed that Bazaine was by that time approaching Verdun, and he ordered the half of the Second Army farthest west (II Corps, XII Corps, and Guard Corps) to march on Verdun in the hope of intercepting Bazaine’s army. The other half of the Second Army (III Corps, IX Corps, and X Corps), together with Goeben’s VIII Corps from the First Army which Moltke had transferred to the Second Army, had crossed the Moselle the night before at Corny. Those three corps were awaiting further orders from Moltke.

Bazaine’s army made little progress on August 15. At the end of the day, the French vanguard was at Vionville and the rearguard at Gravelotte. Prussian General Albert von Rheinbaben’s 5th Cavalry Division was shadowing the movements of the French army from south of the Vionville Road and attacking French outposts.

Of all the Prussian infantry corps, General Constantin von Alvensleben’s III Corps was the closest to Bazaine’s actual position on the morning of August 16. It had reached the village of Gorze at 2 am, which put it five kilometers south of the Vionville Road.

At dawn on August 16, Louis-Napoleon finally departed for Chalons in his royal carriage accompanied by two regiments of Imperial Guard cavalry. A short time later, Prussian cavalry blocked the Vionville Road. When Bazaine learned of that, he ordered the column on that road to halt.

Alvensleben assumed the French troops at Vionville formed Bazaine’s rear guard, and without orders to engage the enemy he nevertheless ordered General Ferdinand von Stulpnagel’s 5th Division to attack what he believed was the back of the French rear guard at Rezonville, while the 6th Division marched west to Mars-la-Tour in an attempt to cut off the front of the French rear guard. Frossard’s II Corps easily repulsed Stulpnagel’s piecemeal attack. While the infantry was attacking, 90 Prussian guns deployed on high ground south of Vionville and began shelling French positions on the plateau to the north.

At 11:30 am, General Karl von Buddenbrock’s 6th Division went into action on Stulpnagel’s left. Buddenbrock’s men attacked Frossard’s left, capturing lightly held Vionville but failing to drive Frossard’s soldiers out of Flavigny. The artillery of General Francois Canrobert’s VI Corps, positioned north of Vionville, inflicted heavy casualties on Buddenbrock’s troops. By then, Alvensleben had realized the severity of his situation. He was not facing the French rear guard; he was facing Bazaine’s entire army.

Alvensleben, whose infantry was alone on the battlefield until such time as General Constantin Voights-Rhetz’s X Corps arrived, asked Rheinbaben to launch a cavalry attack to silence Canrobert’s guns. At 2 pm, General Adalbert von Breedow assembled his 800 cuirassiers and uhlans for the difficult mission. In an effort to lessen the casualties they would take on their advance, von Breedow led them through depressions in the landscape that partially concealed them until they were within several hundred yards of their objective. Just before 2 pm, Canrobert had ordered the infantry posted among the guns to withdraw to protect them from the Prussian artillery fire. This worked to von Breedow’s advantage because there were no support troops to protect the French artillerymen when his horsemen galloped into their midst, slaying as many of them as possible before the French cavalry intervened. “Von Breedow’s Death Ride,” as the famous charge was called, silenced many of the French guns but at the cost of 420 cavalrymen.

After making a forced march from its Moselle crossing, Voights-Rhetz’s X Corps arrived in mid-afternoon to reinforce Alvensleben’s III Corps. The 19th and 20th Divisions of the X Corps deployed at Mars-la-Tour and Vionville, respectively. At 3:30 pm, General Emil von Schwartzkoppen ordered his 19th Division to assault what he believed was the French right flank northeast of Mars-la-Tour. In actuality, the division found itself making a frontal assault against Ladmirault’s IV Corps. Ladmirault’s riflemen easily broke up Schwartzkoppen’s attack.

With little else to try, the Prussians resorted to another cavalry attack. Rheinbaben led his two remaining cavalry brigades around the French right flank, but the French had three divisions of cavalry on the field. The Prussian cavalry, despite being outnumbered, was able to drive the French away from Mars-la-Tour, ensuring that it remained firmly in Prussian hands.

At twilight, Prince Frederick Charles arrived on the battlefield with reinforcements from Goeben’s VIII and Manstein’s IX Corps. The prince ordered an attack on Rezonville intended to collapse the French left flank, but nightfall interrupted the attack before it could achieve its objective. The Battle of Mars-la-Tour cost the French 17,000 casualties, compared to 15,800 Prussian casualties.

At dawn the following day, Bazaine ordered his corps commanders to fall back six kilometers to a long ridgeline just east of Gravelotte. He was reluctant to march his army to Verdun and risk the Prussians forcing him to fight a battle on open ground. “I will resume my march in two days if possible, and will not lose time, unless new battles thwart my arrangements,” he wrote to Louis-Napoleon. Bazaine simply did not want to abandon the vast storehouses of Metz regardless of the consequences. He hoped that the Prussians would suffer such severe casualties in the coming battle that they would be forced to abort their invasion.

The Army of the Rhine moved to its new position on the high ground west of Metz on August 17. Most of the army spent the afternoon entrenching, with the exception of Canrobert’s VI Corps, which had not carried its entrenching tools. The 12-kilometer line stretched from the Rozerieulles Plateau in the south along the Amanvillers Ridge to Saint-Privat in the north. The French left, anchored on the Moselle, was particularly strong owing to a number of walled farms on the east bank of the Manse Stream. The one major weakness was that the French right did not rest on any physical barrier and was vulnerable to being turned. The French army was deployed left to right as follows: Frossard’s II Corps, Leboeuf’s III Corps, Ladmirault’s IV Corps, and Canrobert’s VI Corps. General Charles Bourbaki’s Imperial Guard Corps was stationed next to Bazaine’s headquarters at Fort Plappeville behind the left wing, and General Francois du Barail’s Cavalry Corps was stationed behind the right wing.

The Prussian cavalry had been so badly shaken in the Battle of Mars-la-Tour that Moltke decided not to press it to conduct reconnaissance of French movements until it had rested. Instead, Moltke would have to rely on the infantry to perform that task. Thus, Moltke ordered the Second Army on the morning of August 18 to march northeast on a wide front to intercept the French if they tried to march to Verdun via a more northern route. As for the First Army, it was to concentrate at Gravelotte and await further orders.

At 10 am, Manstein reported to the Second Army commander and also to Moltke that he believed the French right flank was positioned around the village of Amanvillers. However, Manstein had located the French center, not the right. Prince Frederick Charles immediately issued orders to the rest of his army to turn east toward Metz. The Prussian Guard and XII Corps marched east on the Doncourt Road, and the Prussian III and X Corps marched in that direction along the Vionville Road.

A half hour later, Moltke issued orders to Manstein to attack the French at Amanvillers. Manstein’s guns were already in action against Ladmirault’s IV Corps and his troops deploying for attack when a dispatch came from Prince Frederick Charles ordering him to suspend the attack. The Second Army commander had received reports that the French right flank was situated at Saint-Privat to the north and not at Amanvillers.

Manstein initially deployed 54 guns against the French IV Corps atop the Amanvillers Ridge, but they took up a position within range not only of Ladmirault’s cannons and mitrailleuses, but also of entrenched French infantry that fired on the gunners with their Chassepot rifles. “A hail of shell and shrapnel … answered the war-like greeting from our side,” wrote Prussian staff officer Julius Verdy du Vernois. “The grating noise of the mitrailleuses was heard above the tumult, drowning the whole roar of battle.”

At 1 pm, Manstein ordered his guns pulled back until his infantry arrived to provide protection for them. An hour later, his 18th and 25th Divisions had arrived, but Manstein was reluctant to order a frontal assault considering the devastating firepower that the Chassepot gave the French infantry. He wanted to see what result the Prussian attack on the French right would have before ordering his men to charge the ridge. There was no reason not to continue to shell the French positions. The Krupp guns were rolled back to their original places and began a punishing bombardment of Ladmirault’s IV Corps. The Prussian artillerymen “fired without interruption, smothering us in shells,” wrote General Ernest Pradier of Ladmirault’s IV Corps.

Steinmetz had arrived on the battlefield at noon and retaken control of Goeben’s VIII Corps without Moltke realizing it. The septuagenarian First Army commander ordered Goeben’s artillery and Zastrow’s VII Corps artillery to deploy north of Gravelotte and begin bombarding Frossard’s and Leboeuf’s troops on the Rozerieulles Plateau behind the Manse. Altogether, Steinmetz was able to mass 150 guns that began a steady barrage against the French positions. The Prussian shells smashed enemy guns and inflicted severe shrapnel wounds to enemy riflemen who crouched for protection in their trenches.

At 2 pm, Steinmetz ordered Goeben to lead three brigades, two forward and one in reserve, in an assault on the Saint-Hubert Farm on the opposite side of the Manse. Steinmetz reasoned that if the Prussians could capture the farm, it could be used as a forward artillery position to support a subsequent attack on the plateau.

Like finely detailed embroidery, the western slope of the Rozerieulles Plateau was stitched with trenches above and below and on both sides of the Saint-Hubert Farm. At 2:30 pm, a sea of blue-uniformed Prussian infantry streamed down the west ravine and plunged into the stream above and below the causeway that led toward Saint-Hubert. Inside the walled farm was a single battalion of the 80th Line Regiment of the 4th Division of Leboeuf’s III Corps. As they splashed through the stream, the Prussians heard the unmistakable thud of bullets into human flesh as French infantry fired on them. With great discipline, the Prussian riflemen advanced into the storm of bullets. The Krupp guns at Gravelotte zeroed in on the farm and blew it apart. The French still held two nearby farmhouses as well multiple rows of trenches on the west slope of the plateau. From these positions they poured a withering fire at the Prussians who sought to secure the ruins of Saint-Hubert.

At 3:45 pm, the fire from the French 12-pounders slacked off as the crews awaited the arrival of more ammunition. Steinmetz misinterpreted this as a French withdrawal and ordered Zastrow to prepare his division for an attack on the Rozerieulles Plateau. Goeben, whose corps had taken heavy casualties in the first assault, advised against it, but the headstrong Steinmetz ignored him. Like Goeben’s attack, Zastrow’s also employed two brigades forward with one in reserve to exploit a breakthrough.

By that time, Moltke had learned that Steinmetz was ordering the assaults, but he permitted them to proceed even though he thought it was foolhardy. Zastrow’s attack followed the course of the Rozerieulles Road, which swung past Saint Hubert and curved south toward the Point du Jour farm toward the village of Rozerieulles. Point du Jour was held by line infantry of Verge’s 1st Division of Frossard’s II Corps. Zastrow’s men never made it to the plateau. They encountered a gale of shot and shell from Chassepots, mitrailleuses, and muzzle-loaded artillery that stopped them cold.

Steinmetz, who could not see the assault because of a tract of forest that blocked his view, for some unimaginable reason believed it had succeeded. He therefore planned to reinforce it. He ordered the 1st Cavalry Division and four batteries to advance east on the Rozerieulles Road. Only one regiment, the 4th Uhlan, made it to the plateau, where it suffered 50 percent casualties in a matter of minutes. One of the batteries unlimbered on the edge of the plateau, but all of its guns were soon captured. Another unlimbered at Saint-Hubert, but counterbattery fire silenced all but one of its guns. By that point, the Manse ravine was littered with dead soldiers and horses and smashed artillery equipment.

By that time, the Prussian Second Army was preparing a major infantry assault on the opposite flank. It took Prince August of Wurttemberg’s Guard Corps nearly five hours of countermarching before it reached its attack position. The XII Corps, which also was marching northeast toward the French right flank, was about one hour behind the Guard Corps. At 3 pm, Prince Frederick Charles ordered a limited attack by the Guard against the village of Saint-Marie-Aux-Chenes, less than a kilometer from Saint-Privat, designed to drive out the 94th Line Regiment from the French VI Corps. Once the village had been captured, Wurttemberg directed the Guard to deploy its 100 guns in an arc and begin shelling the French positions in front of them.

At 4 pm, the vanguard of the XII Corps arrived at Saint-Marie-Aux-Chenes, and Prince Fredrick Charles directed Crown Prince Albert of Saxony to continue north with his three divisions of Saxons to the village of Roncourt, to put it in a position to launch a flank attack on Canrobert’s VI Corps.

To pin down Canrobert’s corps so it would not be able to shift troops to check the Saxon flank attack, Prince Frederick Charles decided it was necessary to send his corps forward in a frontal attack against Saint-Privat, even if that meant subjecting it to heavy losses. The Prussian Guard had 18,000 men ready for battle, more than twice the number of men in Canrobert’s corps. However, Canrobert’s men held the high ground, and a portion of them would receive the attack from inside the walled village.

Prince Frederick Charles wanted to pin down the right flank of Ladmirault’s IV Corps so it could not reinforce the French VI Corps. To achieve this objective, Wurttemberg ordered the 3rd Guard Brigade at 4:45 pm to attack General Ernest Courtot de Cissey’s 1st Division of the IV Corps at Amanvillers. The French riflemen cut down 2,000 Prussian guardsmen before they could get close enough to use their inferior Dreyse rifles.

Wurttemberg had deployed the other three Guard brigades to attack Saint-Privat. The 1st Guards Brigade formed up north of the Briey Road, and the 2nd and 4th Brigades assembled south of the Briey Road. Despite their esprit-de-corps, the veteran guardsmen must have felt a gnawing in the pit of their stomachs as they looked across the long expanse of open ground they would have to cover to reach the French line on the ridge to their front. Wurttemberg sent the 4th Guards Brigade forward at 5 pm against the 4th Division of Canrobert’s corps. The guardsmen made it to within 800 yards of the French line before they were pinned down like the 3rd Guards Brigade to their right.

At 5:45 pm, Prince August ordered the 1st Guards Brigade positioned north of the Briey Road to advance against Canrobert’s 1st Division, which its commander had split in half to defend both Roncourt and Saint-Privat. With its officers shouting, “Forward, Forward!” to keep the riflemen advancing, the guardsmen suffered heavy casualties not only from the front by those enemy riflemen at Saint-Privat, but also in the flank from those deployed at Roncourt. Nevertheless, they followed the tactics of the other Guard brigades, advancing by rushes toward their objective. Seeing that the 1st Guards Brigade would not be able to reach the village without reinforcements, Prince August ordered his 2nd Guards Brigade, which was his last, to push directly up the Briey Road toward the objective. The 2nd Guards Brigade closed to within 700 yards but stalled after losing nearly all of its field officers.

While Crown Prince Albert continued on to Roncourt with his infantry, he left behind a portion of his artillery that deployed on the left of the Guards artillery. In addition, the Prussian X Corps, which was approaching the battlefield, sent forward some of its guns. This gave Frederick Charles 208 guns with which to shell Saint-Privat. At 6:30 pm the Krupp batteries at Saint-Marie-Aux-Chenes began a steady bombardment that lasted 40 minutes. The fused shells struck the walls of the village, sending chunks of stone careening through the air. By the time the bombardment ended, the village had been heavily damaged, and flames from fires that had started in the houses leaped toward the sky.

Before it could join the assault on Saint-Privat, the Prussian XII Corps had to drive the French out of Roncourt. The Saxons launched their attack on the village at 5 pm. General Henri Pechot’s 1st Brigade of the 1st Division of the French VI Corps put up an impressive defense against the Saxons for two hours, but at 7 pm Pechot ordered his men to fall back to the relative protection of thick woods behind the Amanvillers Ridge.

By twilight, the Guard had already lost about 8,000 killed and wounded in its frontal assaults on Saint-Privat, but when the Krupp guns stopped firing at 7 pm, the Guards and the Saxons launched a simultaneous assault designed to carry Saint-Privat. Bugles and drums filled the air as guardsmen rose up to resume their assault and Saxon infantry charged up the ridge toward the walled village. At the same time the Guards and Saxons attacked Saint-Privat, Manstein ordered his 25th Division to storm the Amanvillers Ridge and engage Ladmirault’s IV Corps in an attempt to pry it from the ridge.

At Saint-Privat, the French and the Prussians fought house to house through the burning village in the gloaming. Fighting was particularly fierce in the walled cemetery in the center of the village, where the 4th Foot Guards Regiment of the 1st Brigade stormed through the gates and drove out French soldiers who attempted to make a stand in that small space. In an hour-long bloodbath, the Prussians slowly gained control of the village, forcing the survivors of Canrobert’s 1st Division to flee into the woods to the east. At great cost in lives, the Prussians finally secured Saint-Privat at 8 pm.

As the Prussians fought to capture Saint-Privat and Roncourt on their left, Steinmetz continued to send troops against the strong French position on the Rozerieulles Plateau on the Prussian right. When King William rode forward to confer with him at 5:45 pm, Steinmetz wrongly assured his monarch that his troops had gained a foothold on the plateau and requested permission to send reinforcements. Equally uninformed as to the actual state of affairs on the Prussian right, William nodded his assent and withdrew. Gathering a brigade each from the Prussian VII and VIII Corps, Steinmetz sent them forward at 6 pm. An hour later, General Eduard Fransecky’s Pomeranian II Corps, which belonged to the Second Army, arrived on the Prussian right, and Steinmetz persuaded Fransecky to send his 3rd Infantry Division against the entrenched French positions. The situation went from bad to worse when shells from the Krupp guns began landing amid the advancing Pomeranians. “Excellency, our own brothers are shooting at us!” cried the Pomeranians nearest Fransecky.

At 8 pm, soldiers from the three Prussian corps that had been sent forward on the Prussian right began streaming back along the road and through the fields toward Gravelotte. In the darkness, Prussians moving up fired into the backs of those already engaged, causing mass panic. “All is lost! All is lost!” the soldiers cried as they moved swiftly west in their blood-spattered uniforms.

Bourbaki had resisted Bazaine’s efforts throughout the afternoon to send the Imperial Guard into battle piecemeal. At 6:15 pm, one of Ladmirault’s staff officers arrived at Bourbaki’s headquarters and implored him to send reinforcements immediately to the right flank. Bourbaki, together with the staff officer, rode at the head of General Joseph Picard’s 2nd Guards Division as it set off at 6:45 pm for the right flank. When they were halfway there, they found themselves in the midst of a large body of soldiers from the French VI Corps moving south toward Metz. Bourbaki had been under the illusion that he was going to commit his troops as a reserve to win the battle rather than to serve as the rear guard for a retreat.

“You promised me a victory, but now you’ve got me involved in a rout!,” Bourbaki spat at the staff officer. “You had no right to do that! There was no need to make me leave my magnificent positions for this!” Rather than try to rally the retreating French, Bourbaki ordered his column to countermarch to its original position.

Ladmirault’s IV Corps was hard pressed after the panicked retreat of the VI Corps to its right. At that point, Ladmirault’s men were being assailed by the Prussians from three sides. When the French riflemen learned that the Imperial Guard was not coming to their assistance, the soldiers abandoned their position without orders and began moving south toward Metz.

Ladmirault descended the east slope of the Amanvillers Ridge and rounded up whatever troops he could find. He established a rear guard on the right wing of the army astride the road from Saint-Privat to Metz using Pechot’s brigade and several regiments of cavalry. Although Bourbaki led his infantry toward Metz, he ordered his artillery to remain behind to bolster Ladmirault’s rear guard.

At 10 pm, Bazaine issued orders for the French army to withdraw toward Metz. He believed his units’ ammunition had been so severely depleted by the battle on August 18 that it would not be able to fight on the same ground the following day. Moltke, who along with King William had witnessed the rout of the Prussian right wing at Gravelotte, had no idea that his troops had won the battle until he received a report in the middle of the night informing him that the Prussian Guard and XII Corps had driven the French right wing from the field. This guaranteed that Bazaine’s army would have to try to break out from Metz. Given Bazaine’s conservative mind-set, it was unlikely that he would be able to do so against the larger, better led Prussian forces confronting him.

The Prussians lost 20,000 killed and wounded compared to French losses of 12,500 killed, wounded, and captured. The French soldiers had fought valiantly and had nothing of which to be ashamed. They knew full well that they had lost the battle because of Bazaine’s poor performance as an army commander.

MacMahon tried unsuccessfully to reach Metz with his 120,000-strong Army of Chalons, but the Prussians prevented him from doing so. While the First Army and part of the Second Army laid siege to Metz, the other half of the Second Army, which Moltke had renamed the Army of the Meuse and placed under the command of Crown Prince Albert of Saxony, conducted joint operations with Crown Prince Frederick’s Third Army against MacMahon.

The two Prussian armies outmaneuvered the French Army of Chalons, driving it steadily away from Paris. MacMahon’s army soon found itself besieged in Sedan. On September 1, MacMahon attempted unsuccessfully to break out of Sedan. The following day, Napoleon III surrendered himself to the Prussians, and MacMahon’s army surrendered shortly afterward. On September 4, the French overthrew Louis-Napoleon’s Second Empire and replaced it with the Third Republic. On September 19, the Prussians besieged Paris.

Bazaine tried halfheartedly on August 31 to break out of the encirclement but subsequently surrendered on October 27. On January 18, 1871, the German princes met at Versailles to proclaim the creation of a unified German Empire. Later that month the two sides signed an armistice. Under the terms of the Treaty of Frankfurt signed May 10, 1871, Bismarck forced the defeated French to cede Alsace and part of Lorraine, as well as to pay Prussia an indemnity of five billion francs. The harsh indemnity was designed to impoverish France for the foreseeable future so that it would not be able to meddle in the affairs of the young German empire. However, France eventually recovered. Less than a half century later, an even more terrible war between the two nations broke out.

A consequence of the Prussian victory here and the war was their acquisition of Alsace and Lorraine which left desire for revenge on the part to the French. All of this were component parts leading to WW I. There are times when victory has unintended results when thinking the immediate situation is resolved.