By David A. Norris

Under sunny skies, favorable winds pushed Captain Mark Robinson and the 74-gun ship of the line Shrewsbury on September 5, 1781, toward a stormy encounter with an old enemy. The captain was deep into his third war with the navy of France. An old hand among the Royal Navy’s officers, Robinson had been promoted to lieutenant back in 1746. As captain of the Worcester in the English Channel three years before, he had enjoyed the service and loyalty of a young acting fourth lieutenant named Horatio Nelson.

Nelson was now serving elsewhere, and Robinson might well have wanted his help on that day. Three or four hours earlier, one of Robinson’s superiors, Rear Admiral Sir Samuel Hood, was warmed by the prospect that “the British fleet had a rich and plentiful harvest of glory in view” as they neared Cape Henry, Virginia. From the English decks, the sailors beheld a fleet of French ships of the line, nearly immobilized by contrary winds and tides. September 5 looked like it would be the day that Rear Admiral Thomas Graves would destroy the fleet of François-Joseph-Paul, Comte de Grasse, rescue the redcoats of Lt. Gen. Charles Cornwallis’s army from siege by a combined French-Continental army, and perhaps hasten the end of the rebellion of His Majesty’s colonies in North America.

By 4 pm, prospects were less rosy for the British. A change in the tide and a few hours’ maneuvering saw the French ships ready in line of battle. Surging ahead, the Shrewsbury approached the enemy from an awkward oblique angle. When they were within musket shot, at least two French ships raked the Shrewsbury with their broadside arrays. In return, Robinson could for the moment only protest with his bow chasers.

In a short time, the Shrewsbury’s fore and main topsail yards were shot down. French cannon balls lodged in or punched through masts and yards, shredded the sails, and slashed standing and running rigging. Once on the verge of helping rescue Cornwallis from the troops of General George Washington and his French allies, the Shrewsbury now needed help herself.

One of the most important battles of the American Revolution was not fought on American soil, but a few miles out to sea off Cape Henry, Virginia. The Battle of the Virginia Capes, also known as the Battle of the Chesapeake, ended with no ships sunk or captured, and a casualty list rivaling only a minor battle or a large skirmish in a land war. But the results echo as loudly in history as the guns of Trafalgar. For without this naval battle outside the Chesapeake Bay, the British army of Cornwallis would have shrugged off the siege of Yorktown rather than surrendering to General George Washington on October 19, 1781.

The Revolutionary War had ground to a stalemate by 1779. British forces had their successes, such as taking New York City, but the Crown’s troops were unable to inflict a decisive defeat on the rebel, who was now getting aid from France. Seeking to force an end to the rebellion, the British opted for a new strategy. An invasion of the southern colonies could cut the rebellious regions in two. London believed that thousands of Loyalists in the Carolinas would rally to the king’s colors.

From the captured port of Charleston, South Carolina, Cornwallis marched inland in the autumn of 1780. He found himself beset by patriot guerrilla attacks. At King’s Mountain, South Carolina, on October 7, 1781, patriots from the western Carolinas destroyed a Loyalist army also gathered from the back country. Afterward, Loyalist recruits came in small numbers rather than the legions once anticipated.

To support Cornwallis’s operations in the South, the British commander in North America, General Sir Henry Clinton, dispatched 1,600 troops from New York to Virginia. Commanded by a new British general, the recent defector Benedict Arnold, they captured Richmond, Virginia, on January 5, 1781, before returning to the coast. There, they occupied Portsmouth, a convenient port giving access to the sea, the Chesapeake Bay, and the rivers of the Virginia interior.

Washington was with the bulk of the Continental Army in the northern states. He now had reinforcements from France. An army under Lt. Gen. Marshal Jean-Baptiste-Donatien de Vimeur, Comte de Rochambeau, had landed at Newport, Rhode Island, in the summer of 1780 to join Washington.

Ships of the French navy under Rear Admiral Charles Rene Dominique Sochet, Chevalier Destouches were also based at Newport. Early in 1781, a storm temporarily scattered the British blockaders off Newport. Destouches dashed off to Virginia to relieve the pressure on the patriots and harass British ships that were attacking the French merchant trade.

Little came of this February 1781 operation. Winter storms were more dangerous than the enemy. A British 74-gun ship was wrecked and another dismasted. Destouches reached the Chesapeake, but the British ships sailed up the Elizabeth River into shallow water where the larger French ships could not pursue. After snapping up one British frigate, the Romulus, the French sailed back to Newport.

In March, Destouches tried, with a larger fleet and some troops, to reinforce the French-Continental forces already in Virginia. A British fleet under Rear Admiral Mariot Arbuthnot, commander of the Royal Navy’s North American Station, followed them from New York after learning of Destouches’ plans.

In the Battle of Cape Henry, on March 16, 1781, the French came out ahead in a tactical sense because of the rough weather. With their ships pushed by the heavy winds down toward their lee sides, which faced the enemy, the British could not risk opening their lower gun ports. The French ships, though, were pushed so the lower guns on their windward sides pointed upward and could be used to good advantage. They heavily damaged three of Arbuthnot’s ships of the line. However, Arbuthnot won a strategic victory as the smaller French fleet turned around for Newport.

Far from the sea, the war on land had taken a fateful turn. Cornwallis’s redcoats defeated Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Greene and a patriot army at Guilford Courthouse near Greensboro, North Carolina, on March 15, 1781. But Cornwallis had won a pyrrhic victory that left his army dangerously weakened and isolated in hostile territory. The British headed for the coast, reaching Wilmington, North Carolina, on April 7. Leaving Wilmington on April 25, Cornwallis joined Arnold’s and other British troops at Petersburg, Virginia, on May 20.

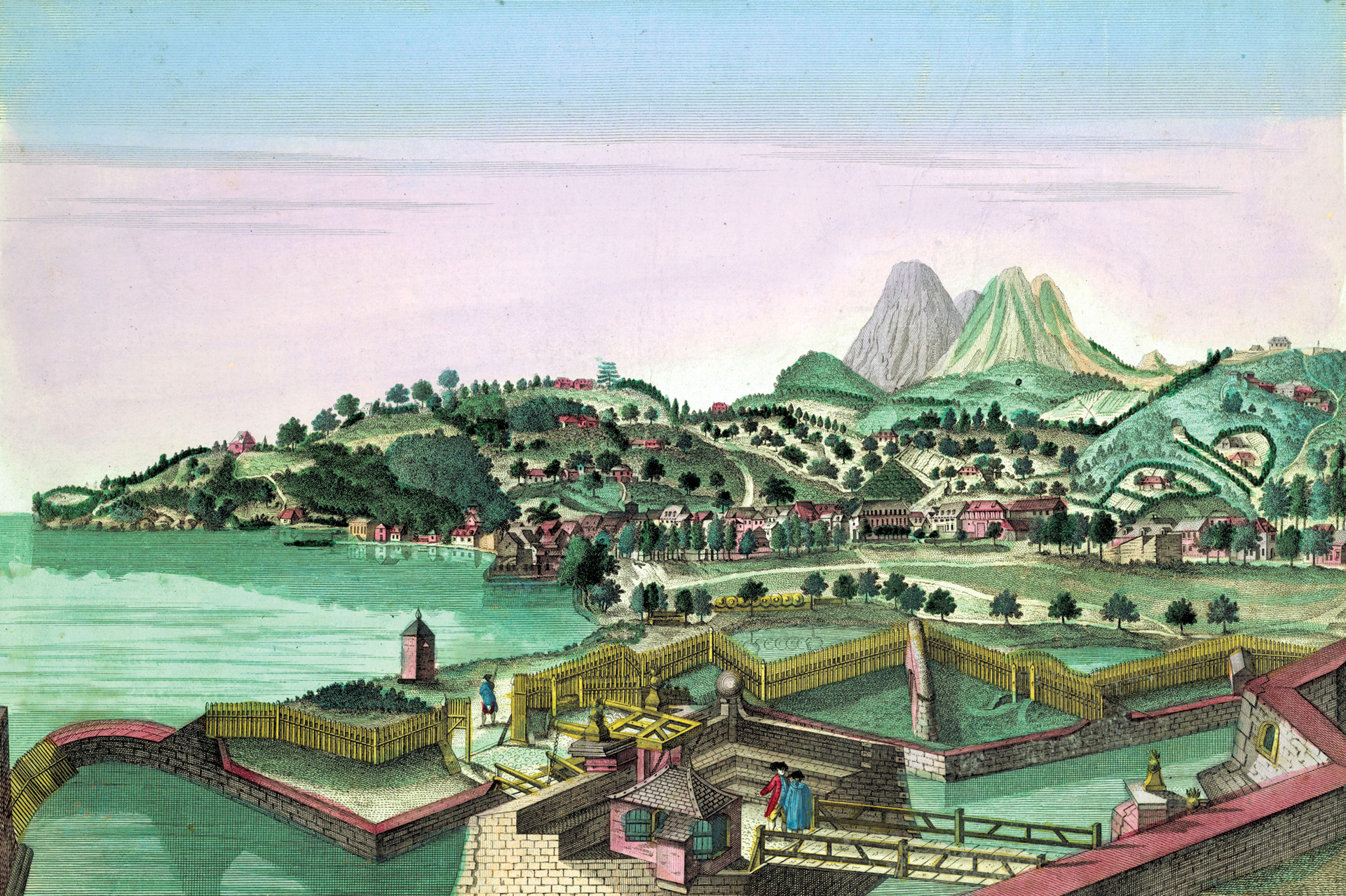

In Virginia, the Chesapeake Bay gave easy access to the sea and the potential protection of the Royal Navy. About 12 miles wide, the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay is bracketed by Cape Charles to the north and Cape Henry to the south. Cape Henry partly shelters an indentation in the coast called Lynn Haven Bay, between modern-day Norfolk on the west and Virginia Beach to the east. In 1781, and now, the main shipping channels pass between Cape Henry and a shoal called the Middle Ground.

Finding Portsmouth an unhealthy location, the British settled at a place called Yorktown. On the Virginia Peninsula, a neck of land between the York and James Rivers, Yorktown is about 10 miles southeast of Williamsburg, the old capital of Virginia. Jamestown, settled in 1607, was just south of Williamsburg but was essentially abandoned by 1781. Yorktown seemed healthier than the coast, and across the river at Gloucester was accommodation for the navy.

Despite the geopolitical considerations of the war raging on the North American continent, much European attention focused on the Caribbean. Although the island outposts of the major powers were tiny compared to the rebellious Thirteen Colonies, the Caribbean islands yielded tremendous profits from sugar plantations.

In the spring of 1781, France sent a large fleet of 23 ships of the line commanded by de Grasse across the Atlantic. Destined first for the Caribbean, they departed from the port of Brest on March 22. With them were 150 merchant ships and transports. To prevent delays, the slowest vessels were taken under tow by the ships of the line.

Bypassing the war to the north, the great French convoy arrived off Martinique on April 28. The next day, de Grasse fought the Battle of Fort Royal against a smaller British fleet under Admiral Samuel Hood. No ships were sunk, and the French cut through the British blockade to relieve Martinique.

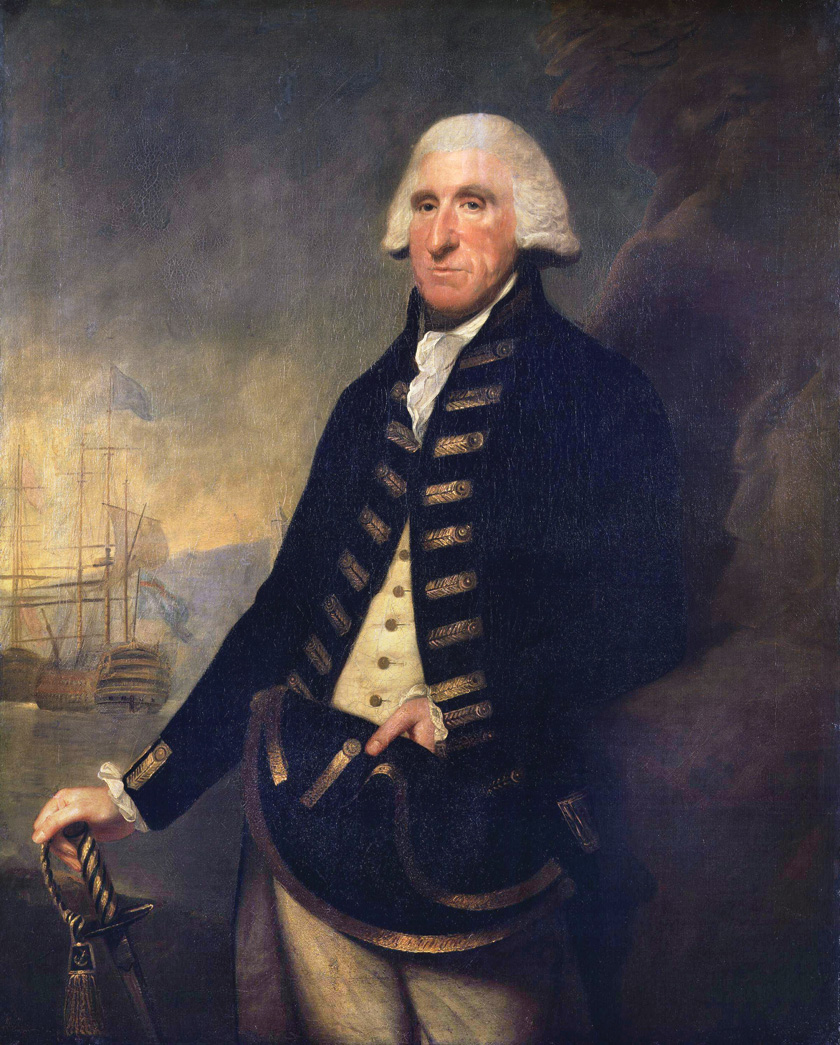

Command changes soon shook up the naval situation in the New World. At Newport, Destouches was replaced by Vice Admiral Jacques Melchior Saint Laurent, Comte de Barras. Among the British, Arbuthnot returned to England, and Rear Admiral Thomas Graves was placed in charge of the ships in New York. In the Caribbean, the capable but ailing Admiral George Brydges Rodney went home on leave. Hood filled Rodney’s shoes as commander of the navy’s Leeward Islands Station.

After taking the British island of Tobago, de Grasse sailed to Cape-Français on San Domingue (now Cap-Haitien in modern-day Haiti). There, on July 6 he met the Concorde, a French frigate bearing messages from Washington and Rochambeau. Although setbacks afflicted Cornwallis in North Carolina, the revolutionary cause was desperate. New York City was firmly in British hands, and the combined French-Continental forces around the city could not recapture it. Virginia was now coming back under British control, cutting off the northern and southern colonies from each other. The patriots were short of money and supplies, and even Rochambeau’s army was pinched for funds. Rochambeau appealed to de Grasse for emergency aid. The French Navy had to arrive in strength to counter the Royal Navy, and France needed more soldiers in America. A vast amount of money was urgently required. Rochambeau had only enough money to pay his troops until August.

Rochambeau’s appeal to de Grasse left the details to the admiral. De Grasse had two options before him. One was to attack the British main stronghold of New York City. If this succeeded, the British would have to withdraw their forces in Virginia to respond.

The other option was for de Grasse to swoop down on the Chesapeake Bay and cut off the British forces in Virginia from the sea. It was this second option that bore the greatest promise of success, and de Grasse seized the opportunity. One factor prodding the French commander was probably the passenger list of the Concorde. On board were 25 American pilots familiar with the shoals and channels of the Chesapeake Bay.

At this crucial moment, de Grasse showed remarkable insight and planning. By delaying the departure of merchant convoys for France, he was able to assemble 28 ships of the line. He managed to borrow more than 3,300 troops, promising the governor of San Domingue to return them by November. The French admiral turned to his Spanish allies in Cuba for aid. They did not consider sending direct help to Virginia but agreed to patrol the coast of San Domingue against the British. In Havana, the Spanish governor and prominent citizens helped raise the money de Grasse needed.

On August 5, the French expedition sailed for the Chesapeake. De Grasse was aboard his flagship, the 110-gun Ville de Paris. With him was the Marquess St. Simon in command of the French soldiers. By August 24, they were off Charleston. Luck was with them; they snapped up several small British ships that might have given away their location and direction. On one of them was Francis Rawdon-Hastings, Lord Rawdon, a British commander en route to England after resigning due to poor health. The convoy went on to the Chesapeake and anchored in Lynn Haven Bay on August 30.

Learning that de Grasse was in motion, Washington’s troops slipped away from their positions around New York City and started marching to Virginia. On August 25, Count de Barras sailed from Newport en route to Virginia. His eight ships of the line escorted 18 transports loaded with 1,000 French troops and siege artillery intended for use at Yorktown.

Before Rodney left for England, he drafted orders for Hood to sail to the Chesapeake. Partly, the move would get the bulk of the British Caribbean fleet out of harm’s way for the hurricane season. The “Great Hurricane” of October 1780 had cost the British two ships of the line and 10 smaller vessels destroyed. Already in 1781, a hurricane sweeping over Jamaica on August 1 dismasted two frigates and destroyed a third, the Pelican. Captain Cuthbert Collingwood, commander of the Pelican, survived the wreck to serve as one of Nelson’s admirals at Trafalgar in 1805.

But Rodney also expected de Grasse to dispatch part of his force to Virginia and wanted Hood on hand to stop them. Three ships of the line went with Rodney to England, and two more were ordered to guard Jamaica. So when Hood sailed from Antigua on August 10, he had only 14 ships of the line.

Unlike the good fortune found by de Grasse on his voyage to Virginia, Hood had quite a bit of bad luck. Two frigates he sent with messages for Graves in New York were lost. But Hood’s ships, which benefitted from copper-plated hulls which minimized shipworm damage and drag from aquatic growth, made such good time that they outsailed the French and reached the Chesapeake Bay on August 25. They were five days ahead of de Grasse and finding the bay empty, they sailed on toward New York. At that point, Graves had recently learned that de Barras had left Newport, so he was about to set sail for Virginia. At the moment, New York station had only five sail of the line plus a 50-gun two-decker available.

On August 31, Hood and Graves combined their ships off New York. Although Hood had far more ships with him, Graves outranked him and so took command of the combined force of 19 sail of the line, the 50-gun ship, six frigates, and a fire ship.

One day before Graves and Hood made their rendezvous, de Grasse reached the Chesapeake and anchored in Lynn Haven Bay. As they arrived, a small boat approached one of the French ships. One man in the boat hailed them and asked for Lord Rodney. A French sailor answered back in fine English. Learning that the men on the boat were Loyalists from Virginia, the French invited the men on board. The colonial Tories were taken aback when they saw that the foot soldiers on the ship wore coats of white instead of red. Brought below, where the officers were eating dinner, the visitors learned that they were prisoners. Fresh, sweet Virginia melons intended for Admiral Rodney, brought from the boat, ended up on the dining tables of the French officers.

St. Simon and his troops boarded about 40 ships’ boats. About 1,900 French sailors and officers were detached from the ships to convey the infantry up the James River to join troops already there under the Marquis de Lafayette. From Yorktown, a bold move from Cornwallis and his 8,000 troops might have smashed either the reinforcements or Lafayette’s smaller main force, but the British remained inside their fortifications and did not interfere with the transfer of St. Simon.

De Grasse also detached several frigates and four ships of the line. They bottled up the British in the York River and guarded the James River in case Cornwallis tried to break out of Yorktown and escape back to North Carolina.

Washington was on his way south with another 4,000 French troops and 2,000 patriots. On September 5, he reached the head of the Elk River, a tributary that flowed into the Chesapeake Bay in northern Maryland. He wrote to prominent men in the region pleading for the loan of boats to ferry part of the army over the Elk. The rest of the force marched around the river and continued overland.

On the morning of the same day Washington reached the Elk River, lookouts aboard a French frigate in the Chesapeake sighted sails in the distance. At first, they hoped it was de Barras coming in from Newport, but soon they realized that they saw the approach of a British fleet.

De Grasse ordered his ships readied for battle. He had 24 ships of the line available, but he was still missing the 1,900 men from the boats sent with St. Simon. Even with about 10 percent of each crew on detached duty, they would have about 18,100 men and 1,822 guns. Graves was far outnumbered and outgunned, with 11,311 men and 1,408 cannon.

Admiral Graves approached Cape Henry without knowing where the French were. British cruisers prowling off the Delaware River from the north had not seen them, and Admiral Graves had not yet made contact with his captains watching the Chesapeake. As the British neared Cape Henry, the 74-gun Alfred was in the lead, as part of the six ships of the division under Admiral Hood. At 9:30 am, the frigate Solebay signaled that the French fleet was in sight to the southwest. Mild winds from the northeast favored the British, steadily pushing them toward the enemy under fair skies.

At 11 am, Graves ordered the fleet into line of battle. “On account of the close but confused manner in which their ships were anchored,” a trait a British observer scoffed at as “customary with the French nation,” it appeared that de Grasse had no more than about 15 sail of the line.

All morning contrary winds and tides pinned the French in Lynn Haven Bay. At noon, with the ebb tide, French sailors took axes and chopped their anchor cables. After marking the anchor positions with buoys, they steered to meet Graves’s ships. Their fleet moved out in a straggling procession that hardly passed for a line of battle. A few ships in the lead quickly made it into the open ocean, but those farther behind had to tack several times to get out of the bay and lagged far behind. Four vessels, the Pluton, Marseillais, Bourgogne, and Diadème, were close together in the forefront. Following behind after a gap in the line were the Réfléchi and then the Auguste, the 80-gun flagship of Rear Admiral Louis-Antoine, Comte de Bougainville, commander of the lead section of the fleet. There were more gaps in the line. Winds pushed the center with the Ville de Paris, de Grasse’s flagship, to windward, and the rear division was even farther out of alignment.

The British noticed that several French ships were isolated far ahead of possible help. Graves could have signaled a general chase, letting each of his ships sail individually and choose a target among the enemy. If this maneuver worked, they could have fallen upon and overwhelmed several of the foremost vessels of the French before the others could come to their aid. After the battle, Hood claimed that this would have been the correct choice. Instead, Graves took a more cautious approach, and the British ships were held tightly in line of battle.

Capital ships of Europe’s navies usually fought in a long, single line of battle, and hence were known as ships of the line. This way, the ships presented their broadsides to the enemy and thereby brought the maximum number of guns into action. Holding to the line of battle was not actually required of British admirals, but at this time they generally did.

Graves may well have been overly cautious in not ordering a general chase at noon, but he had good reasons for not doing so. It was not guaranteed that the wind would bring his fastest ships down on the isolated French van before the enemy drew its line together and the British fleet was outnumbered. It was risky for the smaller fleet in an engagement to break up its line of battle. Not only were there five more enemy ships of the line, the French ships on average were bigger and carried more guns (and of heavier caliber) than their English counterparts.

With the wind continuing against them, the French consumed a great deal of time to tack past the Middle Ground shoals and clear Cape Henry. About 2 pm, most were in a rough line heading almost due east, although the rear vessels still lagged behind.

Graves’s ships were in line nearly parallel to de Grasse but heading in the opposite direction, toward the bay. By 2 pm, the foremost British ships neared the shoal water of the Middle Ground. The van of the French fleet was about three miles due south of the flagship London, roughly the center of the British formation.

Directed by Graves, the signal “wear together” was hoisted aloft from the London. This order meant his ships would turn around and sail in the opposite direction. Together, the ships turned from heading west to south and continued to turn counterclockwise until they were sailing pointed east. Wearing together was a complicated maneuver, and the time it consumed allowed the French to tighten their formation. Graves’s signal reversed the order of the line of battle. Hood’s ships were then in the rear. In the lead now were six vessels under Rear Admiral Francis Samuel Drake, a relative of the famous Elizabethan sea dog Sir Francis Drake.

Now fourth in the line of battle, Drake’s 70-gun flagship Princessa was the oldest ship present that day. Built about 1730 for the Spanish navy, she fell to the British during the War of Jenkins’ Ear in 1740.

Ahead of Drake were the Intrepid and Alcide. In the lead was the 74-gun Shrewsbury, commanded by Robinson. Two spots in line behind Drake and the Princessa, sailors aboard the 74-gun Terrible had all the pumps running at full capacity. After twice running ashore during her time in America, the Terrible was plagued with leaks. A collision with the Alcide several months before aggravated the damage. Somewhere during this series of misfortunes, her foremast was sprung. The cracked and split wood required careful handling to keep the mast from going overboard.

Originally, the half crippled Terrible was assigned to the rear division of the line. Because Graves’s signal reversed the original order of battle, the Terrible was now sixth in line. Observers aboard British and French ships watched as the Terrible started dropping out of line. Drake sharply rebuked the Terrible by firing three shots across her stern, and she was steered back into her place.

To use every possible asset, Graves ordered the captain of his single fireship, the eight-gun Salamander, to prime the vessel. This involved removing the combustibles from storage and setting a powder train. With luck, the crew could draw near an enemy ship, set their craft on fire, and escape in a boat while the burning fireship drifted down upon the foe.

Graves was on the same tack as the French but at a considerable distance from them. To close the gap between the fleets, the admiral signaled for the lead ship to turn to the starboard. Probably Graves intended for all the ships to turn simultaneously with the Shrewsbury, bringing the entire line closer to the French but keeping their bows parallel. But he kept the signal for line of battle flying as well. Interpreting these signals, his captains steered to starboard, one by one, keeping to a new single line of battle headed by the lead ship. Instead of drawing near the enemy in a parallel line, they would strike them at such a sharp angle that only the leading vessels would be close enough for effective combat.

By 4 pm, the leading ships of the two fleets were within range. The 74-gun Montagu, eighth in the British line, opened fire about 4:05 pm. Its guns bore on the fifth and sixth ships in the French line, which proved to be the Réfléchi and the Auguste. Admiral Howe felt that the ships in the center, such as the Montagu, opened fire at a “most improper distance.” Improper or not, some of the first British cannonballs tore into the Réfléchi, killing her commander, Captain M. de Boades.

Leading his division into battle, Louis-Antoine, Comte de Bougainville drew on the experience of a long and notable career. He had retired from the navy in 1780. Expecting a quiet life on his estate with his new wife, he was soon called back into service by King Louis XVI.

Captain Robinson and the Shrewsbury soon came into action against the French. At close range, the Shrewsbury was exposed to broadsides from several French ships. Twenty minutes after the crew’s first shot, at 4:45 pm by their reckoning, the Shrewsbury’s foretop yard crashed down to the deck, followed by the main and mizzen topyards. Three minutes later, Robinson fell, shot in the thigh. Evidently the captain was quickly borne below deck for the surgeon to treat him. At 5:10 pm, a clerk tersely noted, “Captain Robinson lost his left Leg.”

Dozens of the Shrewsbury’s men were hit. French fire ripped sails and riggings and dismounted one gun and then another. By 5:15 pm, the vessel “had not a Brace, Bowling [bowline] or hardly a Fore or Main Shroud Standing,” according to the Captain’s Journal of the Shrewsbury.” Following behind them, the Intrepid’s officers saw the Shrewsbury had lost her fore and main topsail yards. Steering closer, Captain Anthony James Pye Molloy hailed and asked them to cease fire so he could take their place in the battle. Ten minutes later, the Shrewsbury was still in the fighting alongside the enemy when its first lieutenant was shot dead.

At 5:30, the Intrepid passed the Shrewsbury and sheltered her from enemy fire, Molloy’s guns “keeping her fire well up & closing with the Enemy’s van,” as stated in the Captain’s Journal of the Shrewsbury. The Shrewsbury ceased fire, no longer able to keep her place. In 15 minutes she drifted three cable lengths from the line of battle, her crew busy fixing the masts and repairing the rigging.

Carrying only 64 guns, the Intrepid confronted two enemy 74s, the Pluton and the Marseillais, and took fire from others. Steering to the rescue of Robinson’s ship cost the Intrepid heavily: 21 dead and 35 wounded. Shots punched through the hull and pierced or lodged in the masts and spars, including “two very dangerous ones” in the fore topmast. But the Intrepid inflicted heavy damage on the two French 74s, and they fell out of the line.

Admiral Graves kept the line of battle signal aloft, locking his ships into a single inflexible row. A line of battle was determined by an imaginary line drawn from the van to the commander’s flagship. As the London was barely within extreme long range of the French, this meant that the half of the British fleet following the flagship would be fixed at an even greater distance from the action.

Confusion with the signals plagued the British. Even in the best of circumstances, and even with using repeater frigates, signals were often hard or impossible to read due to battle smoke or the action of the winds on the flags. Aboard the London, the line of battle signal was lowered at 4:11, and the signal to engage close went up. Graves felt the ships were starting to bunch together and raised the line ahead signal again at 4:22 pm, and again lowered it at 4:27 pm.

Raising the contradictory signals for the ships to stay in line of battle and to closely engage the enemy, Admiral Graves assumed that his captains would understand he meant for them to maneuver so as to bring their line of battle close to the French and parallel with them. Signals and fighting instructions were a complicated matter, and mistakes in interpreting or executing them could lead to court-martials. Graves had not had time to meet with his captains and explain his views of tactics. Therefore, his commanders could not know how much discretion he allowed his officers to deviate from his signals.

Adding to the uncertainty, the North American and West Indian stations did not use identical signal books. Hood strongly criticized Graves in post-battle writings, but on the day of battle he never broke from the line, strictly following the signals from the flagship.

Admiral Bougainville was in the thick of the battle aboard the Auguste. Among the dead and wounded was the second officer. One shot severed the foretop bowline, which endangered the working of the ship. A sailor who climbed aloft to repair the line was shot dead, and a second man who took up the job was also killed. When no volunteers came forward for a third try, Bougainville shouted to the sailors that he would give the coins in his purse to the man who fixed the bowline. A sailor quickly climbed up and made the repair, then called down to the deck to turn down the reward, saying that he didn’t perform the task for money.

During the battle the Auguste took 54 cannon shots in her hull, and 70 shots pierced her sails. Nine men were killed, including her first lieutenant. Among the 54 wounded was an Ensign Hoguenhausen. He was one of several Swedish officers serving in the French navy during the battle, seeking action and potential advancement at a time when Sweden was neutral and at peace.

Aboard the Terrible, the heavy recoil of her guns shook her hull. The shock of the guns further strained the hull planking, and the pumps had even more water to expel from the ship.

Far back in the British line, two places behind the London, the 74-gun Resolution was the most distant ship from the van to receive fire. Even at that distance, French shot killed three men and wounded 16 and did enough damage to keep the carpenter and boatswain busy after the battle. Her captain, Lord Robert Manners, had a very narrow escape. “The peak of my hat was shot off by a ball,” he wrote his brother. “I felt a slight inconvenience from it for a few moments, but no injury.”

The fickle winds shifted, pushing one way and then another. De Grasse’s center and rear struggled to reach the focus of the action. It was the avant-garde of both lines, under Bougainville and Drake, that took the brunt of the fighting. So, although outnumbered to begin with, Graves fought the battle with only two thirds of his ships. Many of de Grasse’s ships also took no part in the battle.

Farther toward the end of the British line, Admiral Hood’s ships never caught up with the fighting. The master’s log of the Centaur noted that they “found the Enemys Shot go over us.” Aboard the Invincible, the crew saw the London fire a broadside, but it could “easily observe the Shott fall Considerably short therefore we persisted in not firing a single Gun.” The Monarch did fire several shots, but they splashed into the sea so far short of the French that the gunners stopped wasting their ammunition. The fireship Salamander took no active part in the battle.

Sunset darkened the seas about 6:30 pm, and the firing faded away. All of the combatants’ ships were still afloat. However, four of the French vessels were out of action. Six of Graves’ ships—almost one third of his fleet—were also unfit for combat. One damage report after another noted that many of the masts and spars were “wounded” by enemy shot and needed immediate repair.

British losses were 90 dead and 246 wounded. The butcher’s bill was by far the heaviest on the two ships in the lead. Of 532 men on board at the start of the action, 66 men fell on the Shrewsbury, 14 dead and 52 wounded. With Captain Robinson recovering from losing his leg and the first lieutenant dead, command fell to the second lieutenant. In the hours after the battle, she made a signal of distress. With “all her masts and yards so shattered,” the Shrewsbury was unable to keep her place in line of battle. Three guns were dismounted. Five shot had punched into the hull below the waterline. With all pumps working into the night, the ship still took in about 14 inches of water every four hours.

The Intrepid was in little better shape than the Shrewsbury. Her masts were standing but were in fragile shape from being shot through in several places. A damage report noted, “Sails and rigging very much cut particularly the topsails—All the boats damaged.”

Losses were lighter in ships toward the center of the line, and seven of the 19 Royal Navy vessels had no casualties at all.

Most accounts place the French losses of dead and wounded combined at about 230. Captain de Boades of the Réfléchi was dead, and five other captains were wounded. Many of the names of the dead of de Grasse’s fleet are inscribed on the Yorktown French Memorial with soldiers of France who died during the final campaign of the Revolutionary War.

On September 6, the fleets lingered within sight of each otherOn September 6, the fleets lingered within sight of each other, but no action took place. Afterward, the British and French hovered near each other for nearly a week, maneuvering and watching one another. De Grasse was most concerned with getting back to the Chesapeake to support the land operations. Graves’s fleet was not in shape for battle. The Shrewsbury and the Intrepid were wrecked by enemy fire and needed considerable repair. Two other ships, the Ajax and the Terrible, had heavy battle damage to aggravate the havoc already wreaked upon them by teredo worms.

While the French ships were away from Lynn Haven Bay, the British frigate Iris slipped into the site of their anchorage on September 8. Originally, the Iris was the American frigate Hancock, but the ship had been captured and taken into the Royal Navy in 1777. In the bay, the surface was dotted with buoys marking the locations of the French anchors dropped in their haste to get to sea. After cutting some of the buoys from the cables, the Iris rejoined the fleet.

Far out to sea, a break in the standoff came on the night of October 9. The main topmast of the Intrepid snapped and fell overboard. With the British fleet halted to wait for the Intrepid to make repairs, the French got away.

Aboard the Terrible, the crew fought a losing battle with the sea. At best the pumps could only just keep up with the water seeping into the hull. Pumps and men alike were wearing out from the constant labor. A board of officers from around the fleet agreed that the hull was leaking so badly that the ship would never make it to the American coast. Captain Finch divided his crew and supplies among the fleet. Left to her fate, the Terrible was set afire on the night of September 11.

Steering back to Lynn Haven Bay on September 12, Graves found that de Grasse had returned ahead of him. Reinforced by de Barras, the French had 36 ships of the line, exactly twice Graves’s total. The siege artillery brought on the French transports was soon put in place to bombard the redcoats trapped in Yorktown.

Adding to Graves’s woes, the Iris had returned to Lynn Haven Bay with another frigate, the Richmond, to finish cutting the French anchor buoys. De Grasse’s return trapped the frigates. In a sharply fought little battle, the Iris and the Richmond held out against several ships of the line for 11/2 hours. The French fired more than 200 rounds before the smaller British ships struck their colors. Respectful of the valor of the British captains, de Grasse returned them their swords.

Admiral Graves had no choice but to return to New York for repairs and to gather reinforcements. While there, the admiral used his influence to get Captain Robinson of the Shrewsbury a special pension.

General Clinton ordered the fleet to return to relieve Cornwallis. It took almost one month to get the augmented fleet to sea. Graves departed on October 12 with 7,000 more troops. His fleet grew to 25 ships of the line with the arrival of three from England and two from the West Indies. They arrived off Cape Henry on October 24. But Graves was too late. Loyalist refugees picked up by the fleet reported that six weeks after the battle at sea the British army at Yorktown surrendered to General Washington on October 19, 1781.

For a fleet action with only moderate damage, the Battle of the Virginia Capes had earthshaking consequences. The successful French defense of the Chesapeake meant that Cornwallis’s situation was hopeless. Even with Cornwallis’s surrender, thousands of redcoats still held much American territory including the major ports of New York and Charleston. However, with the largest field army in the war zone lost, it was clear that a continuation of the war would require a massive effort. To the British public and the elite running the government, it looked like war was not worth the cost in blood and treasure needed to keep in line a collection of rebellious and only marginally profitable colonies. Fighting simmered along in the Atlantic colonies for nearly two more years, but London was ready to end the war.

Although the American Revolution was practically over after the Virginia Capes and Yorktown, the long-running naval war between France and Britain continued. Less than a year after the disappointing battle off the Chesapeake, the Royal Navy got ample revenge against its old adversaries. At the Battle of the Saints, fought off Dominica on April 12, 1782, Admiral de Grasse and his three-decker flagship Ville de Paris ended up as prisoners of a British force commanded by Admiral Rodney. The contending fleets included most of the ships and men involved at the Virginia Capes.

Although the Royal Navy’s officers felt redeemed by the Battle of the Saints, in a sense the spectacular naval clash made little difference in history. Whatever de Grasse’s mistakes were in 1782, his fleet had already assured America’s break from British rule. The following year, diplomats drafted and signed the Treaty of Paris. In 1783, the United States was a free and independent country.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments