By Christopher Miskimon

During the early spring of 1949, North Korean ruler Kim Il Sung visited Moscow. His nation’s first economic plan had ended in failure after two years; the plight of the country was desperate. Kim had only half the population of neighboring South Korea and each month many North Koreans packed their meager belongings and trudged south in the hope of a better life. As he met with Soviet strongman Joseph Stalin, the mustachioed Georgian asked comrade Kim how things were going in his tiny eastern nation. The Korean dictator told him “the southerners are making trouble all the time.” He complained that South Korean troops frequently raided across the border, sparking frequent skirmishes. Of course, Kim neglected to mention his troops did the same thing just as often. Stalin became angry at learning this and began asking if Kim needed weapons. He admonished the North Korean leader to “strike the southerners in the teeth. Strike them, strike them.”

This conversation set into motion one of the first hot conflicts of the Cold War. On the other side of the world, the United States decided it would not arm South Korea or support it short of a major invasion by the North. While South Korea’s troops had barely a week’s worth of ammunition on hand, the Soviets were shipping tanks, artillery, and fighters to their communist brothers on the northern half of the peninsula. American decision makers wanted defense cuts and the estimation that places such as Korea were safe from attack reinforced that view.

In the end, it seemed both sides miscalculated. The United States did not see the invasion coming and had to scramble to stop it. The North Koreans and their Soviet backers underestimated American resolve to oppose them. The stalemate continues to this day and the war taught the Americans a valuable lesson. They could not rely on nuclear weapons as the sole deterrent to war and had to have a strong conventional force ready. Instead of an easy victory for communism, the Soviets and their clients would heretofore have to deal with a rebuilt American Army, a Navy of nearly 400 ships, and a massive air force for decades to come.

In the end, it seemed both sides miscalculated. The United States did not see the invasion coming and had to scramble to stop it. The North Koreans and their Soviet backers underestimated American resolve to oppose them. The stalemate continues to this day and the war taught the Americans a valuable lesson. They could not rely on nuclear weapons as the sole deterrent to war and had to have a strong conventional force ready. Instead of an easy victory for communism, the Soviets and their clients would heretofore have to deal with a rebuilt American Army, a Navy of nearly 400 ships, and a massive air force for decades to come.

As bad as the Korean War was, it could have been worse. The conflict was just one episode in the two decades when the Cold War formed from the chaos of World War II. It was a period of turmoil as a new order of sorts gradually coalesced from what had existed before. Author Michael Burleigh’s new book Small Wars, Faraway Places: Global Insurrection and the Making of the Modern World, 1945-1965 (Viking Press/Penguin Group, New York, 2013, 587 pp., maps, notes, bibliography, index, $36.00, hardcover) dives into this tumultuous period and dissects all the tiny yet significant details that make it at once fascinating to study and terrifying to consider how it could have turned out.

Rather than try to cover the Cold War in its entirety, the author chooses to concentrate on its first two decades, what he refers to as a transitional period when power passed from the former empires based in Europe to the United States. During this time new nations were born and old ones crumbled, became divided, or were conquered from without or within. Some of these transitions were successful while others were unmitigated catastrophes. Rather than try to cover every conflict, focus is placed on a smaller number of significant wars that typified the era.

Along the way effort is made to show the contrasts of these actions. For example, the United Stated was able to figure out that the insurgency in Algeria, while leftist in bent, was not part of the feared worldwide communist offensive and so did not come to France’s aid with troops, planes, and bombs. In the same decade they failed to see the same thing in Vietnam and became heavily involved. While there were reasons for this failure, it had consequences for America in the following decades.

The author’s choice to focus on essentially the first half of the Cold War is appropriate and works well for the intent of his work. The period to 1965 was more uncertain in many ways; afterward, the Cold War, while still very dangerous, became to some extent more stable and manageable, though it may not have seemed so at the time. He combines views from the people fighting the war on the ground to policy makers at the highest levels of government. There are also hints at how study of these wars may—or may not—have lessons to tell about current world conflicts, some of which have origins in the very period covered in the book. It is well written, thoroughly researched, and has enough detail to please any student of the Cold War.

Women Heroes of World War I: 16 Remarkable Resisters, Soldiers, Spies, and Medics (Kathryn J. Atwood, Chicago Review Press, Chicago, IL, 2014, 256 pp., photographs, glossary, notes, bibliography, index, $19.95, softcover)

Women Heroes of World War I: 16 Remarkable Resisters, Soldiers, Spies, and Medics (Kathryn J. Atwood, Chicago Review Press, Chicago, IL, 2014, 256 pp., photographs, glossary, notes, bibliography, index, $19.95, softcover)

This is the latest in the Chicago Review Press’s series “Women of Action,” chronicling the exploits of women in various fields of endeavor, including warfare. Focusing on World War I, each chapter is a short history on a different woman and her part in the Great War. Many wars have had famous female participant such as Joan of Arc or Molly Pitcher, but beyond the select few, many other women who served are now all but forgotten.

The Russian military has long been more accepting of female soldiers and several of them are covered here, such as Maria Bochkareva, who obtained permission from Czar Nicholas II to join the army. Her dedication to the cause of Mother Russia led to promotion and command of the “Women’s Battalion of Death,” an all-female unit where half the women were educated professionals. Maria believed her unit would fight better if they emulated men, so she ordered them to shave their heads, smoke, and swear. Many left after a few days but the remainder became hardened believers in the value of service to their country.

Torpedo: Inventing the Military-Industrial Complex in the United States and Great Britain (Katherine C. Epstein, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2014, 305 pp., photographs, notes, index, $45.00, hardcover)

Torpedo: Inventing the Military-Industrial Complex in the United States and Great Britain (Katherine C. Epstein, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2014, 305 pp., photographs, notes, index, $45.00, hardcover)

The concept of the military-industrial complex is generally considered a device of the Cold War. This book puts forward a theory that it actually started almost a century earlier in the waning decades of the 1800s. Instead of nuclear weapons and jet fighters, the weapon that began the union of government and arms makers was the naval torpedo.

This new weapon threatened to upset the naval status quo by making the great powers’ advanced warships vulnerable to a small, relatively cheap device that could easily proliferate across the globe to even poor nations. At the same time, developing, manufacturing, and improving the torpedo was an expensive process that required engineers, scientists, and industrialists to cooperate with ministers and naval officers.

Before the torpedo militaries would either buy finished weapons from manufacturers or develop their own designs at government-run armories and arsenals. With the advent of this new shipkiller, the American and British administrations began to invest in private-sector research and development. This was a necessary decision to cope with the increasing costs of technologically advanced weapons as the industrial age matured in the late 19th century. As a result, inventions that came about through torpedo research initiated legal battles when inventors tried to market their designs abroad. To stop this, governments began claiming that the dispersal of such new technology violated national security needs, something that still occurs today.

Telling this tale requires a complex weave of detailed technical information, political maneuvering, and legal dueling. The author manages to pull it all together. Her arguments are sound and shed light on a facet of military history that heretofore has been neglected and unknown.

The Fights on the Little Big Horn: Unveiling the Mysteries of Custer’s Last Stand (Gordon Harper, Casemate Publishing, Havertown, PA, 2014, 408 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $32.95, hardcover)

The Fights on the Little Big Horn: Unveiling the Mysteries of Custer’s Last Stand (Gordon Harper, Casemate Publishing, Havertown, PA, 2014, 408 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $32.95, hardcover)

The story of Custer’s last stand has been refought and retold in so many books and articles over the last 138 years it seems unlikely anything new could be written about it. There is such an enormous body of work on this one short engagement and its aftermath one could spend a lifetime sifting through it. That is precisely what the author of this book did. Visiting the battlefield as a young man, he became intrigued and began researching it, collecting whatever he could find. There are many controversies, legends, and conflicting tales surrounding the demise of the 7th Cavalry that June day in 1876; Mr. Harper spent decades sifting through them all.

While no book of reasonable length could include everything on the Little Big Horn, this book provides an excellent overview, combining accounts from both Native American and white perspectives. It also includes information from more recent forensic investigations of the battlefield and the light they shed on the engagement. Several chapters also cover the aftermath of the fight and burial of the slain. A set of maps in the back of the book help the reader to follow the action in detail.

Dartmouth Veterans: Vietnam Perspectives (Edited by Phillip C. Schaefer, Dartmouth College Press, Hanover, NH, 2014, 370 pp., photographs, index, $29.95, softcover) While many think of universities as refuges from military service during the 1960s, many young men graduated from them and proceeded directly onto active duty. For many of them, Vietnam was their destination. Dartmouth College in New Hampshire has collected the experiences of a number of their Vietnam veteran alumni and published them in this new volume. Each chapter relates the experiences of a different person. There are a number of books on Vietnam that use this format, which will be familiar to many students of that war. This is not a criticism; this style works.

Dartmouth Veterans: Vietnam Perspectives (Edited by Phillip C. Schaefer, Dartmouth College Press, Hanover, NH, 2014, 370 pp., photographs, index, $29.95, softcover) While many think of universities as refuges from military service during the 1960s, many young men graduated from them and proceeded directly onto active duty. For many of them, Vietnam was their destination. Dartmouth College in New Hampshire has collected the experiences of a number of their Vietnam veteran alumni and published them in this new volume. Each chapter relates the experiences of a different person. There are a number of books on Vietnam that use this format, which will be familiar to many students of that war. This is not a criticism; this style works.

All branches of the military are represented in this work and many interesting stories are told. One U.S. soldier working with Vietnamese troops saw several of them decorated by an American general for capturing a group of Viet Cong. Within weeks almost all of them were dead or wounded, prompting the Vietnamese to shun decorations. Another Army officer, a lawyer with the Judge Advocate General, found himself guarding a building with a shotgun during the 1968 Tet fighting. All these accounts are varied but many veterans, Vietnam and otherwise, will find experiences familiar to their own.

Warfare in the Old Testament: The Organization, Weapons and Tactics of Ancient Near Eastern Armies (Boyd Seevers, Kregel Academic, Grand Rapids, MI, 2013, 328 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, bibliography, index, $34.99, hardcover)

Warfare in the Old Testament: The Organization, Weapons and Tactics of Ancient Near Eastern Armies (Boyd Seevers, Kregel Academic, Grand Rapids, MI, 2013, 328 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, bibliography, index, $34.99, hardcover)

Religious studies often avoid warfare even though it is frequently mentioned in the Bible. This new work by a biblical scholar instead focuses on it, attempting to show the armies of the ancient world in the area of the Eastern Mediterranean in a new light. The author shows how six distinct peoples—the Israelites, Egyptians, Philistines, Assyrians, Babylonians, and Persians—organized their hosts for war. Each is alotted one or more chapters to give the reader a vivid portrait of what it may have been like to serve in their respective forces during this crucial period of human history.

Coverage is given to organization, weapons, and tactics using the available historical and biblical evidence. The author also discusses how each army is mentioned and related to in the Bible using references to chapter and verse where possible. For those interested in ancient history and the Bible, there is a scripture index in the back so warfare-related passages can be found in the book more easily.

No Turning Back: A Guide to the 1864 Overland Campaign, from the Wilderness to Cold Harbor, May 4-June 13, 1864 (Robert M. Dunkerly, Donald C. Pfanz, and David R. Ruth, Savas Beatie Publishing, El Dorado Hills, CA, 2014, 168 pp., maps, illustrations, $12.95, softcover)

No Turning Back: A Guide to the 1864 Overland Campaign, from the Wilderness to Cold Harbor, May 4-June 13, 1864 (Robert M. Dunkerly, Donald C. Pfanz, and David R. Ruth, Savas Beatie Publishing, El Dorado Hills, CA, 2014, 168 pp., maps, illustrations, $12.95, softcover)

In May 1864 Union General Ulysses Grant took his Army south deep into Virginia, intending to pummel the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia into final submission. Those Confederates met him at the Battle of the Wilderness and stopped his army momentarily. Before, Union armies had fallen back after a defeat. This time, with Grant at their head, the Union troops maneuvered and kept advancing. He was determined to bring the Civil War to a conclusion.

Over the next month, the two armies ground against each other often in bad weather and with ever increasing casualties. This guidebook allows the reader to follow the course of this campaign across Virginia on a self-guided driving tour. Extensive historical information is included to give an idea of the events at each significant point. Both driving directions and coordinates are given so the tech-savvy can find exact locations on their GPS devices.

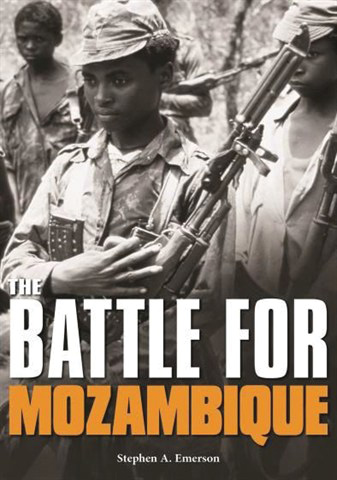

The Battle for Mozambique: The Frelimo-Renamo Struggle, 1977-1992 (Stephen A. Emerson, Casemate Publishing, Havertown, PA, 2014, 288 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $35.00, softcover)

The Battle for Mozambique: The Frelimo-Renamo Struggle, 1977-1992 (Stephen A. Emerson, Casemate Publishing, Havertown, PA, 2014, 288 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $35.00, softcover)

Until recently, the conflicts in Africa during the Cold War-era have been largely overlooked, particularly in the United States. Lately more effort has been made to bring English-language works on these wars to readers, and this new book is part of that effort. The wars involving Angola and South Africa receive more overall attention, but this insurgency in Mozambique was significant in its own right. It lasted 15 years and by its end at least one million Africans were dead.

Like most wars on the African continent during this period it was also complex. The Renamo rebels began as a movement against Zimbabwean guerrillas operating in Mozambique and evolved into an independent nationalist force. Like other groups of the period, for a time they had the clandestine support of South Africa. The author uses accounts of participants from generals and politicians down to frontline soldiers and sailors to tell the story of this unknown war from the perspectives of those who lived through it.

Short Bursts

USS Constellation on the Dismal Coast: Willie Leonard’s Journal 1859-61 (Edited by C. Herbert Gilliland, University of South Carolina Press, $39.95, hardcover). In 1859 a young sailor embarked on a 20-month cruise aboard the USS Constellation on anti-slavery duty off the coast of Africa. His journal provides detail and insight into the ship’s mission, in which it set a record for numbers of slave ships captured.

USS Constellation on the Dismal Coast: Willie Leonard’s Journal 1859-61 (Edited by C. Herbert Gilliland, University of South Carolina Press, $39.95, hardcover). In 1859 a young sailor embarked on a 20-month cruise aboard the USS Constellation on anti-slavery duty off the coast of Africa. His journal provides detail and insight into the ship’s mission, in which it set a record for numbers of slave ships captured.

Home Squadron: The U.S. Navy on the North Atlantic Station (James C. Renfrow, Naval Institute Press, $54.95, hardcover). Before 1874 the American Navy was a collection of individual ships rather than a fleet. From then on the nation shifted to a force of modern warships able to act in concert as a true battle fleet.

An Inoffensive Rearmament: The Making of the Postwar Japanese Army (Colonel Frank Kowalski, Naval Institute Press, $37.95, hardcover.) The author was an American officer on occupation duty in postwar Japan. In 1950, with war in Korea breaking out, he was tasked to quietly begin recreating a Japanese national army.

A Warrior Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of Sweden as a Military Superpower 1611-1721 (Henrik O. Lunde, Casemate Publishing, $32.95, hardcover). For a century Sweden was a great power in Europe until manpower and financial shortages brought it low. During that time the Swedes fought and defeated numerous enemies across the Continent.

Killing Bin Laden—Operation Neptune Spear 2011 (Peter Panzeri, Osprey Publishing, $18.95, softcover). This book is part of Osprey’s Raid series, recounting famous military forays. This volume concentrates on the special operations mission that resulted in the death of Osama Bin Laden.

China’s Battle for Korea: The 1951 Spring Offensives (Xiaobing Li, Indiana University Press, $45.00, softcover). The largest Chinese offensive of the Korean War began in April 1951 and lasted five weeks. This book examines the battle from the Chinese perspective.

In Hospital and Camp: The Civil War Through the Eyes of its Doctors and Nurses (Harold Elk Straubing, Stackpole Books, $19.95, softcover). This book reveals how medicine was practiced during the Civil War both inside hospitals and in field conditions.

In Hospital and Camp: The Civil War Through the Eyes of its Doctors and Nurses (Harold Elk Straubing, Stackpole Books, $19.95, softcover). This book reveals how medicine was practiced during the Civil War both inside hospitals and in field conditions.

The Third Reich Bravery and Merit Decoration for Eastern Peoples (Rolf Michaelis, Schiffer Publishing, $19.99, hardcover). This is a study of an almost unknown award issued by the Nazis to Slavic volunteers serving in specially raised units. Some of these troops fought on the front lines while others performed security duties.

Reporting Under Fire: 16 Daring Women Correspondents and Photojournalists (Kerrie Hollihan, Chicago Review Press, $19.95, hardcover). Just as women have struggled to join the ranks of the world’s militaries, so have they pushed into the news media covering warfare. This book, aimed at a young adult audience, focuses on female reporters from World War I to the present.

The Embattled Past: Reflections on Military History (Edward M. Coffman, University Press of Kentucky, $40.00, hardcover). The author is a well-respected professor specializing in military history. This book collects of a number of his essays on both the world wars and related topics.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments