By David A. Norris

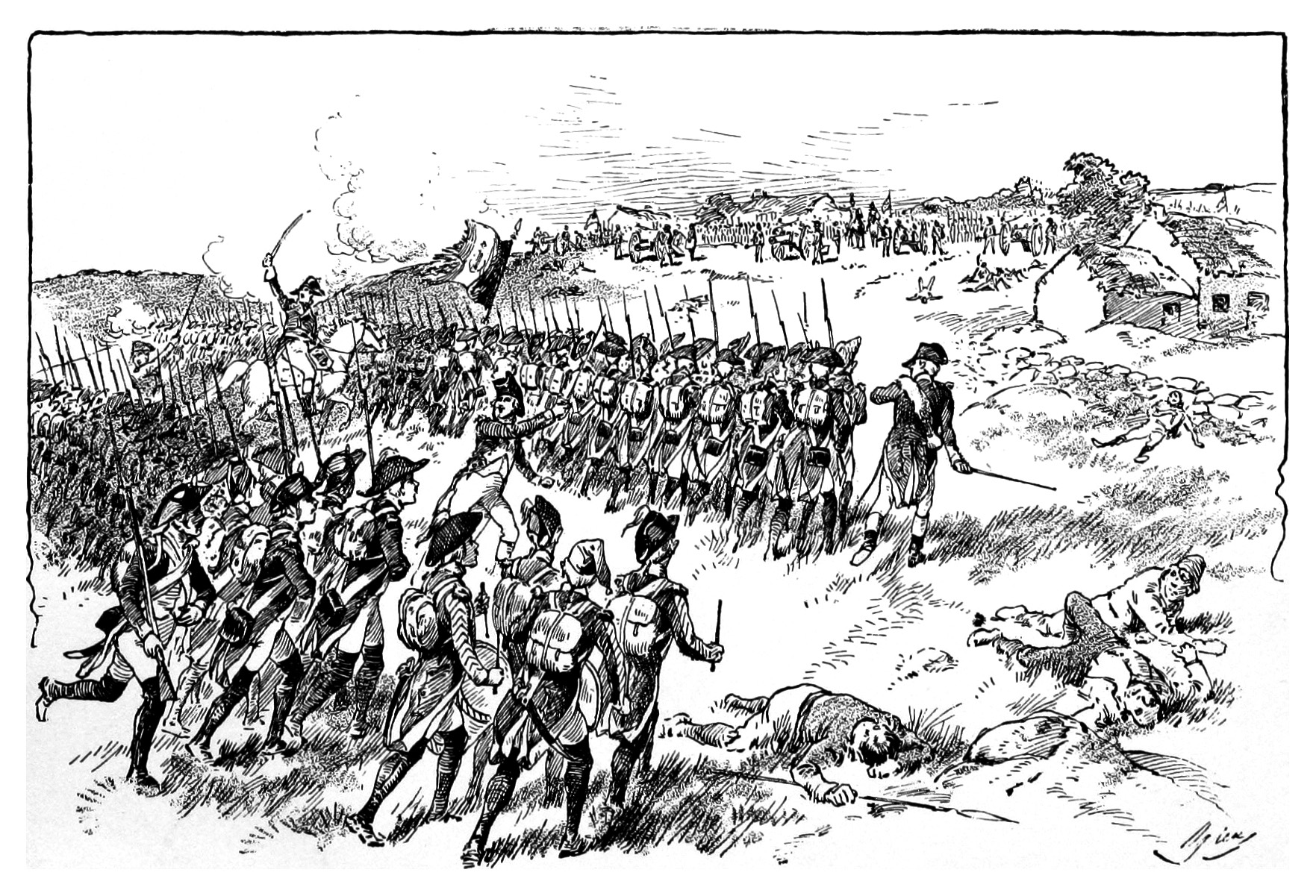

An army of redcoat regulars and militia gazed up the contours of Vinegar Hill in County Wexford, Ireland. What seemed to be new forest growth bristled from the green slopes of the hill. The “trees” of Vinegar Hill were pikes, long ash-wood handles tipped with deadly iron points. Arrayed on the hill was an insurgent army of 20,000, so new that nine-tenths of them were armed with pikes instead of firearms. Whether wielding firelocks or pikes, the Irish patriots on the hill on the morning of June 21, 1798, were confident and surging in numbers. If they could hold out until promised help from France reached them, it could mean the fulfillment of a centuries-old dream: an independent Ireland.

Ireland was ablaze with rebellion in mid-1798. Centuries of oppression by English rulers in London and native aristocrats allied with the British had long sparked hopes of Irish independence. Embroiled in a war with revolutionary France, Great Britain was hard pressed to fight wars in Europe, its vast worldwide network of colonies, and on the seas. Acting with Irish patriots, the landing of a trained and well-armed force of French regulars could furnish the nucleus of an Irish army. Perhaps an Irish George Washington would lead another revolutionary army to victory at another Yorktown.

The United Society of Irishmen was formed in Belfast in October 1791. Inspired by the ideals of the American Revolution, and the hope generated by the beginning of the French Revolution, its members sought independence for Ireland. The society’s original rolls drew many members from the middle class and some from the aristocracy. Catholics, Protestants from the established Church of Ireland and members of dissenting churches such as the Presbyterians joined together in the cause. The authorities in Dublin Castle, the headquarters of British rule in Ireland, were instantly suspicious of the group. In 1793 war broke out between Britain and France, and the society’s embrace of French revolutionary ideas soon got it outlawed.

Working within the political system now seemed pointless. Driven underground, the United Irishmen altered their strategy to armed rebellion. Intervention from France seemed the only road to success. Plans were set to coordinate a rising with the arrival of 14,000 soldiers from France in December 1796. The fleet set sail for Ireland, but storms forced the French troopships back to port.

Leaders of the United Irishmen continued to arrange for a new French invasion force. Throughout Ireland, members of the society hoarded muskets and ammunition to await the time to use them. In the country, thousands of pikes were secretly manufactured and hidden. Miles Byrne, a young County Wexford farmer who joined the United Irishmen, thought that nearly every blacksmith in his part of Ireland was with them. Blacksmiths produced great stockpiles of iron pike blades. Oddly enough, it was getting the handles that caused trouble. Numerous young ash trees disappeared, cut down to make the handles, and this aroused suspicion among the authorities.

As the movement grew, spies infiltrated the ranks of the United Irishmen. Their ties with France alienated many of their original supporters. Other formerly faithful revolutionaries came to fear the widespread violence that would sweep Ireland if there was another revolt, and they became informers.

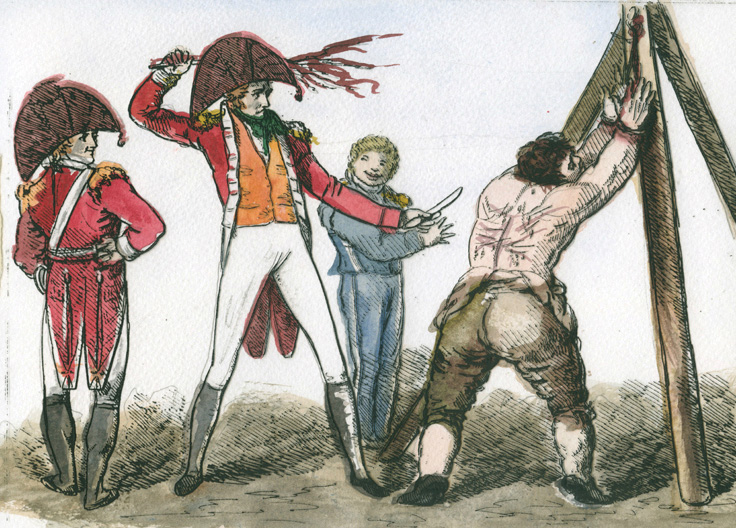

Martial law was declared in Ireland on March 30, 1798. The Crown arrested several top officials of the United Irishmen. Lord Edward Fitzgerald, a prominent revolutionary leader, was fatally shot while resisting arrest in Dublin. Throughout the island, regular troops, infantry militia, and mounted militiamen, called yeomen, raked the countryside searching for suspected rebels and caches of weapons. Soldiers on this duty lived at “free quarters,” meaning they could force civilians to lodge them in their homes and could take whatever food and supplies they needed from the local population. Such broad latitude led to widespread looting.

Regular troops were strict in their searches for rebels, but their officers generally limited their excesses. Militia and yeoman units were much more harsh and vengeful. Suspected revolutionaries were arrested and flogged to extract information and implicate others. Worse were tortures such as “half-hanging” and “pitch-capping.” The latter was a matter of soldiers pouring pitch on the top of a victim’s head and setting it on fire. Despite the crackdown, or perhaps because of it, the remaining leaders of the United Irishmen decided to go ahead with another uprising without waiting for soldiers from France.

On May 23, 1798, parties of United Irishmen set out to seize the mail coaches leaving Dublin, and others were to start taking over the city. These acts signaled sympathizers across the island to begin a nationwide rebellion. The uprising unfolded in a sketchy and haphazard fashion. Most of the mail coaches escaped. With tip-offs from spies, the authorities quickly squelched most of the rebel activity around Dublin and the neighboring counties of Meath and Kildare. A rising in Down and Antrim, in the north, did not begin until a few days later and it was quickly put down.

When the militia was called out to quell civil disturbances in Ireland, the Crown relied on units brought in from other counties to lessen any sympathy felt for the locals. Among the officers sent to County Wexford was Lt. Col. Richard Foote [also spelled Foott], who commanded a detachment of the North Cork Militia composed of men who lived roughly 100 miles away from Wexford. After leaving their quarters in Dublin and coming to Wexford, Foote and the other militia officers arrested or tortured numerous civilians and burned scores of homes in farms and villages.

By May 26, far from preventing a revolt in County Wexford, the militia’s harsh tactics provoked open rebellion. Mostly armed with pitchforks and scythes, scores of local farmers attacked a patrol of yeomen. Two of the horsemen were killed and the rest fled.

On May 27 Foote neared Oulart Hill in Wexford. About 20 yeomen rode with more than 100 foot soldiers. They neared a force of several hundred countrymen, led by a local priest, Father John Murphy.

A native of the area, Murphy traveled to Seville, Spain, to study for the priesthood. Returning to Ireland, he became the curate at the village of Boolavogue. Murphy had previously been a voice of moderation, swearing allegiance to the Crown and discouraging notions of rebellion. But, his peaceful convictions were overwhelmed by the suffering of his parishioners and the sight of the militia burning his parish church. Men from the surrounding countryside assembled at Oulart Hill to strike back. Most carried pikes, scythes, or pitchforks, but a few dozen of them had firelocks. Murphy’s education and his standing in the community evidently made the farmers choose him as their leader.

Although heavily outnumbered, the militia’s second in command, Major James Lombard, impulsively ordered the men to charge. The ditches and hedges that enclosed many small fields in the area provided cover for ambushers and limited the view of the soldiers. Rushing toward the assembled farmers, they were surprised when the rebels’ hidden gunmen stood and fired a heavy volley from their muskets, blunderbusses, and fowling pieces. Few of Foote’s part-time soldiers had ever endured a volley of such hostile fire. Their ranks cut up by the enfilade fire, the militia broke and ran.

As the soldiers fled, a young militia musician fell wounded and called out for help. A Lieutenant Ware of the North Corks, escaping on his horse, stopped to help him. Ware tried to lift the boy onto his horse, but before he could do so, he was slain by a pikeman.

While the mounted yeomen bolted from the field and escaped, almost every man of the foot militia was run down and shot or hacked to death. Scattered for about one mile from the line where the first soldiers fell, about 100 enlisted men and six officers were left dead on the field. Only Foote, mounted on a fast horse, one sergeant, and three privates survived to give the alarm in Wexford town. The insurgents lost only six men.

To an army equipped with pitchforks and pikes, the capture of more than 100 muskets from the battlefield was an invaluable prize. A local loyalist noted that the insurgents also captured “about 57 rounds of ball-cartridges per man, they not having fired above three or four rounds when they attempted to charge them with bayonets.”

With Father Murphy as one of their leaders, the growing army of rebels set their sights on the town of Enniscorthy. Situated on the River Slaney, Enniscorthy is about 12 miles upstream from where the river reaches the town of Wexford and flows into the Irish Sea. Built by the Normans, Enniscorthy Castle rose above the town. A stone bridge spanned the Slaney.

On May 29, Father Murphy’s army attacked the town’s 300-man garrison. Although the insurgents greatly outnumbered the soldiers, most of the attackers were still armed only with pikes. The rebels used a simple but effective tactic to compensate for their lack of firearms. They gathered a herd of cattle and horses. Goading the animals with their pikes, they stampeded the herds toward the soldiers and broke up their formations. After heavy fighting that saw much of Enniscorthy set afire, the garrison was driven out and retreated to Wexford. Rebel losses were unknown, but the militia of the garrison lost four officers and 71 enlisted men dead.

Political divisions in 1790s Ireland were not altogether simple and clear-cut. The majority of Ireland’s inhabitants were Catholic, and laws restricted their political and civic rights. Only in 1778 could they own and bequeath property. By 1793 Catholics could practice law, hold ranks up to colonel in the army in Ireland (but not outside of it), and, with sufficient property, vote.

But the Rebellion of 1798 was not a simple Catholic-Protestant clash. Many of the British regular troops actually were Irish who found that military service offered careers and security. Although Protestants dominated the militia, there were many Catholic soldiers on their rolls. Dozens of the rank and file of the militia killed at Oulart Hill were Catholic. Although the rebellion was in part an Irish Catholic uprising, many of its leaders were Protestant landowners, barristers, and other men of prominence. Much of the Presbyterian population of the north of the island heartily supported the rebellion.

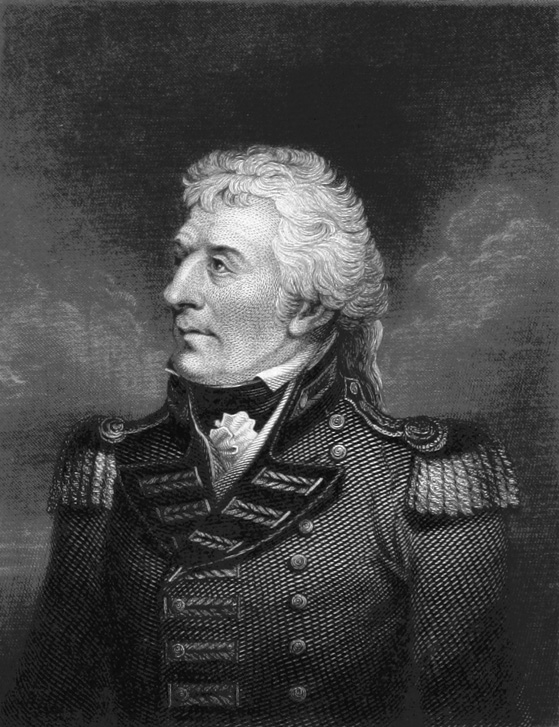

Lieutenant General Gerard Lake commanded the British forces in Ireland. Born in 1744, Lake served in the Seven Years’ War, was captured at Yorktown in 1781, and fought on the Continent against the revolutionary French. He was also a close friend of the Prince of Wales, the future George IV. Although Lake was a heavy gambler, he was one of the steadier members of the prince’s rather disreputable social circle.

Lake oversaw the quick putdown of the rebellion in Kildare and then turned to the growing outbreak in Wexford. His forces included some regular infantry and dragoon regiments, as well as a large portion of part-time or reserve troops, including militia and yeomanry. Among them were militiamen from England, Wales, and Scotland as well as Ireland.

Yeomanry, a term then used for cavalry militia, harkened back to the Middle Ages when yeomen were a class of free farmers. New regiments of yeomanry were raised in the face of threats of a French invasion in the 1790s. They had some latitude in choosing their own officers and could not be sent abroad without their consent.

A 1798 manual, Instructions for the Armed Yeomanry, offers some interesting glimpses into the troubles of commanding these amateur troops. Each yeoman “should take care that no young or idle visitor draw and hack his Sword in play; as its neat and proper edge is most necessary in Service.” They were reminded, when called up, to make it “a point of honor” to be at their assigned posts on time, as “the time is always meant to be precise, whether so expressed or not.”

After taking control of Enniscorthy, the rebels of Wexford assembled their forces there. Despite the efforts of moderate leaders, harsh retribution fell upon the Protestants and loyalists who were caught in the town. The old Norman castle became a prison. Quick court-martials sentenced scores of loyalists to death. Scores were executed with pikes and thrown off the bridge into the Slaney.

Bagenal Harvey, a local landowner and lawyer, had long been a member of the United Irishmen. Arrested and jailed by the crown in Wexford on May 26, he was freed when the town fell on May 30. The rebels appointed Harvey as their commander.

After Enniscorthy, the rebels moved against the town of Wexford. After they smashed a small British column trying to reinforce Wexford on May 29, the town surrendered the next day. By then most of the county had been taken from royal control.

The insurgents split into three separate wings and attacked other royal garrisons. At Tuberneering on June 4, the rebels defeated a detachment of about 750 dragoons and militia. The British commander was killed and three cannons were captured. But otherwise in early June the divided forces were defeated in battles at Bunclody (or Newtonbarry), New Ross, and Arklow. The disciplined formations and musket fire of the trained soldiers saved them. New Ross was a hard-fought battle won in part by the Crown’s advantage in artillery. Taking New Ross would have opened a route for the rebels to move into Carlow and Kilkenny, to the west of County Wexford.

Bagenal Harvey resigned after the defeat at New Ross and a massacre of prisoners the same day at Scullabogue. Philip Roche, a priest who became a colonel in the rebel forces, took over as commander.

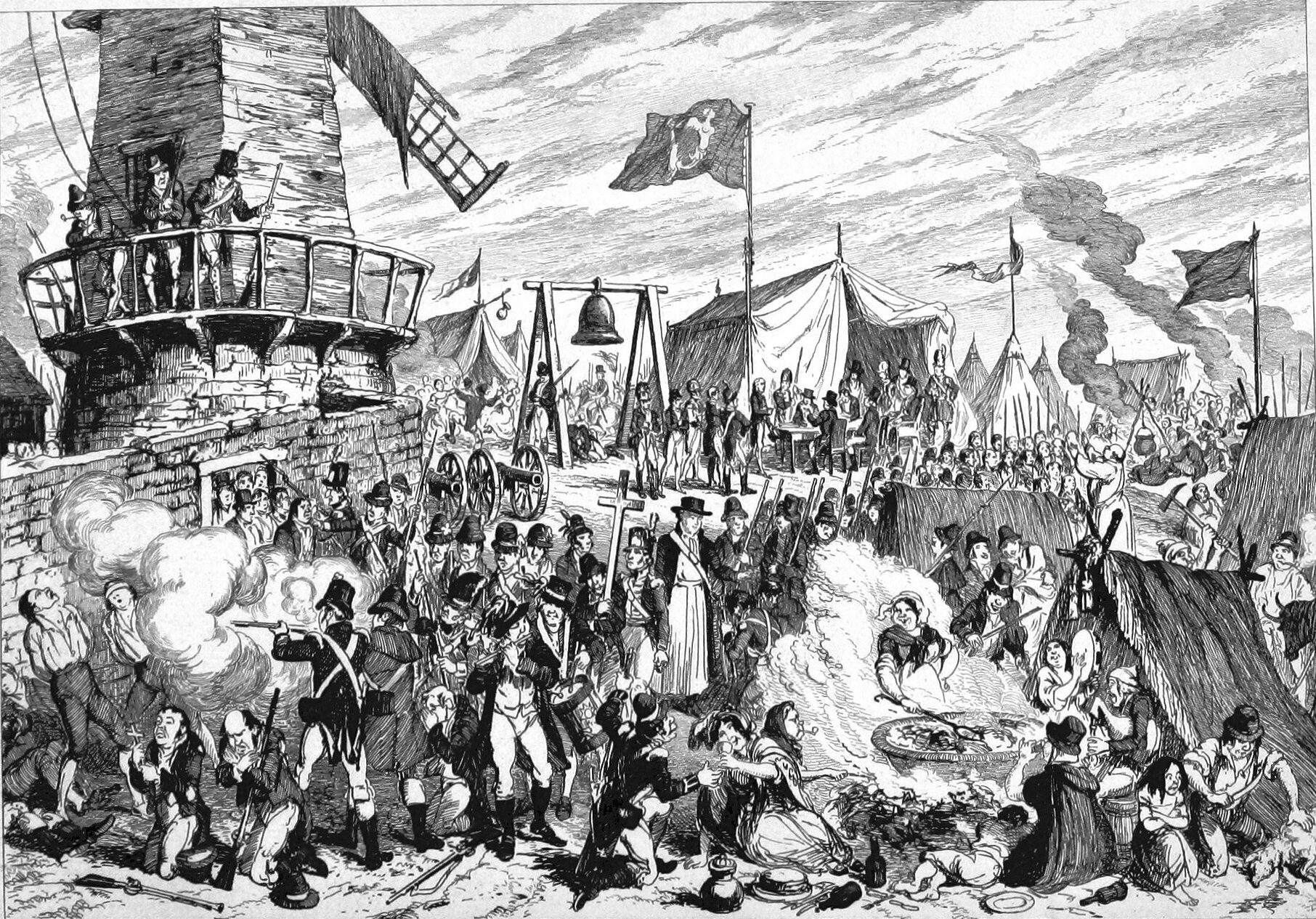

Some days before at Enniscorthy, the insurgents chose a new defensive position. Vinegar Hill rose about 400 feet above the pastures and potato fields across the river from Enniscorthy. Anthony Sinnot, a visitor to the place in 1801, described the hill in The Gentleman’s Magazine as rising from “a gentle swell from a plain till it becomes very steep on all sides, and ends in a craggy summit crowned with the ruins of a windmill.”

In early June, more executions of loyalists and Protestants were carried out on Vinegar Hill, staining its slopes and the walls of the ruined stone windmill with blood. These reprisals in turn inflamed loyalists and the British military and authorities and would lead to a more terrible cycle of bloodshed as angry or grief-stricken people sought revenge. Moderate rebels tried, often in vain, to prevent more executions.

The ad-hoc army made camp and dug some entrenchments on the sides of the hill. Many soldiers and camp followers slept in the open, the weather being mild and pleasant. Others huddled in a colorful array of tents. Made from tablecloths, draperies, blankets, and bed curtains plundered from the town, they were stretched over arches made from bent wooden poles. A bell taken from the church in town was mounted in camp to ring as an alarm in case of attack.

Eventually an estimated 20,000 rebels and dependents were assembled at Vinegar Hill to face the redcoats. But, they were woefully short of firearms. France had promised support but did little about shipping muskets to Ireland. In the weeks leading up to the start of the rebellion on May 23, the United Irishmen collected firearms by breaking into aristocratic homes. Among the Irish forces there was many a fine shot, his aim honed by years of hunting waterfowl in County Wexford. But British officers concluded from their sources that the insurgents had only about 2,000 firearms among them. This meant that 90 percent of the troops had only pikes or other edged weapons to face British muskets and cannons.

Assembling, organizing, and training a new army takes time, which was something the rebels did not have. Previous military experience was also in short supply. Some valuable training came from men who had served in the yeomanry. Many such men had been discharged for suspected disloyalty, and others deserted to join the rebellion. Veterans instructed the recruits in military life and the handling of firelocks. There were no drummers in the new army. Officers assembled their corps by sending out their standard bearers, who marched through camp and called their men.

As to the unit structure of the rebel army, Byrne noted that the force at Vinegar Hill was divided into units referred to as corps. Each corps was composed of men from the same town or locality and so probably varied by size.

To distinguish the units, each corps had its own flag. The Monaseed Corps, named for a village in northern County Wexford, had a fine banner described by Byrne as “adorned with harps and green emblems.” Some young women of their region had sewn the flag and presented it to them.

Rebels of 1798 were called “croppies” by sympathizers and enemies. The term was taken from the short hair styles worn by most of the insurgents. For some, cropped hair affiliated them with the revolutionaries of France, who eschewed wigs and hair powder for simple haircuts. At any rate, short cropped hair was more in keeping with the styles of the country folk who made up the bulk of the rebel ranks.

For uniforms, practically everyone wore their ordinary work clothes. Some wore captured militia hats or coats or other military accoutrements. Byrne noted that few men heeded suggestions to adapt their clothing into uniforms by cutting their coat tails in a similar military style. Some men wore green cockades or wrapped a band of white cloth around their hats, but these insignia apparently were not universally adopted.

At Vinegar Hill, the rebels essentially had only infantry. Some officers had horses, but there were no cavalry units at all. Their artillery amounted to only 13 small pieces. Largest of their guns were two howitzers, of 4.5 and 5.5-inch diameters. There were three brass 6-pounders, one 3-pounder, and seven 1-pounder guns, which were evidently the swivel guns referred to in some accounts.

Experienced gunners seem to have been scarce. During the battle at New Ross, a captured royalist artilleryman was compelled to command one of the rebel guns. He was threatened with death if he did not aim properly, and before the battle was over he was slain for pointing the barrel too high.

Defeats at Bunclody, New Ross, and Arklow had stopped the progress of the rebellion. Uncertain of what course to take, many of the rebels stayed around Vinegar Hill and waited for a British attack. To Thomas Cloney, a young volunteer who joined the insurgents, “all now was disorder and confusion.” Many already bore wounds from skirmishing, and many had seen their homes destroyed. The rebels seemed “divided into parties and cabals, each … urging that the neighborhood from which they came was in the greatest danger.”

On June 20, Lake approached Vinegar Hill with an army of 13,000 regulars, militia, and yeomen, along with an artillery train. Major Generals Henry Johnston and Charles Eustace marched from the west and made camp outside Enniscorthy, about one mile northwest of the hill. Taking one of their field guns, some of the rebels advanced from the hill and skirmished with Johnston, but the attack was not pressed enough to have much effect.

Most of Lake’s men were on the other side of the Slaney from Johnston and Eustace. Lake also sent for more troops under Maj. Gen. Francis Needham, who was about eight miles east at Oulart.

As the great confrontation loomed, Byrne was disappointed to return to the hill and see that little had been done to improve the defenses. He eyed a network of ditches, walls, and hedges at the base of the rise, thinking that they should have been leveled. Leaving them as they were ended up providing cover to the advancing redcoats.

At 5:30 am, June 21, the royal forces opened an artillery barrage against Vinegar Hill. The sound of the guns carried across the 12 miles to Wexford Town. On the British right was Maj. Gen. James Duff, marching on the Ferns Road. Duff had the river to his right and fired on the enemy with a battery of howitzers.

Duff sent part of his force, under Maj. Gen. William Loftus, to a small hill that rose north of the base of Vinegar Hill. Loftus’s hill was very steep, and his way was blocked by some stone field walls. His men broke gaps in the walls. Detaching six guns from their horses, the soldiers pushed the cannons by hand up the hill and opened fire. From their vantage point, Loftus’s guns poured grapeshot down into a section of the enemy line.

Lake was with Lt. Gen. Ralph Dundas, some distance to the left of Loftus. Of the rest of his force, Needham was to move all the way around the royal army to their left, where he could block any possible rebel retreat from the southeast side of the hill. Part of Lake’s forces under Sir John Moore, future hero of the Peninsular War, were ordered to proceed to Wexford rather than take part in this battle.

The confiscated church bell on Vinegar Hill tolled as the insurgents fired their artillery. Some of the rebels wore shakos or brass helmets captured from the yeomanry units they had overwhelmed in the previous days. Everyone expected the arrival of a force under Edward Roche (their commander’s brother) coming up from the south. Roche was believed to be bringing a substantial force of men armed with muskets who could help even the odds with the redcoats.

After the barrage had gone on for 11/2 hours, Lake’s troops pressed forward onto the south slopes of Vinegar Hill. Across the Slaney, Johnston pushed into the town under the cover of his artillery. From upper floor windows, those rebels with muskets poured a heavy fire down on the troops. Pikemen fought the redcoats in the narrow streets.

Some of Johnston’s men brought a 6-pounder gun with them. They had reached an open space in front of the courthouse when a swarm of pikemen poured out of the building. Rushing the soldiers, the pikemen overwhelmed the soldiers and drove them away from the cannon. But, the gun was in rebel hands only a short time. A renewed attack by the soldiers reclaimed the yard in front of the courthouse and took back the gun.

About one-eighth of a mile beyond the courthouse, Johnston’s men neared the town’s only bridge across the river. Resistance collapsed and the defenders streamed across the bridge, aiming to link up with their comrades in Vinegar Hill.

Stubbornly protecting the bridge were William Barker and a corps of rebels under his command. Barker was a veteran of Walsh’s Regiment, an all-Irish unit that served in the French Army. His military experience enabled him to hold the bridge long enough for most of the “croppies” to escape from the town.

Barker had only one gun, a small cannon mounted onto a cart. The gun did little damage to the royal troops but bolstered the morale of the rebels at the bridge. Byrne noted that Barker protected his flanks with the “gun-men,” indicating he positioned his smaller number of musket-equipped men to protect the more numerous pikemen. Barker held the bridge until he fell with a serious wound to his arm.

Johnston ordered his light infantry to charge, but they showed “an unwillingness to do so,” according to a witness. Johnston turned to the Dublin County Militia. Giving three cheers, they rushed toward the bridge, followed by the emboldened light infantry. With the bridge taken, Johnston’s men crossed to unite with the rest of their army.

On the hill, the rebels had only a limited supply of gunpowder. A chronicler of the events of 1798, James Gordon, reported that all through the rebellion the insurgents were short of ammunition and so “used small round stones, and hardened balls of clay, rather than leaden bullets.” Cannons might be fired, according to Gordon, “by applying wisps of straw in place of matches.”

Nonetheless, the forces on Vinegar Hill put up a sharp resistance as long as they could. Lake’s horse was shot from under him at the foot of the hill. Gradually, the redcoats pushed their way up the incline as Johnston forced the last defenders out of the town. Those forced out of Enniscorthy tried to join their comrades on Vinegar Hill, only to find Lake’s redcoats had reached the top. Pulling down the Irish banner from the windmill, the royal soldiers raised their own standard. Johnston’s force ascended the slope of the hill that faced the town.

An hour and a half after the royal infantry began their attack, the rebels ran out of gunpowder and were driven off Vinegar Hill. Escape routes toward Enniscorthy or upstream along the river were blocked, as were the northern and eastern sides of the hill. But, the fleeing army poured through an open space in the British lines, between the royal left and the river. Needham, assigned to plug that opening, was late reaching his destination. Most of the rebels slipped through the break in the lines and escaped to the south, toward Wexford. A short distance from the battlefield, they met Edward Roche’s forces. Although too late for the fighting, Roche helped by fending off the yeomanry who rode in pursuit of the main body of the fleeing army.

“Needham’s Gap” was the subject of considerable speculation after the battle. Loyalists who blamed the commander sneered at him as “the late General Needham.” Some commentators believed that for humanitarian reasons Needham deliberately dawdled to allow the enemy to escape, rather than cornering and slaughtering several thousand people. However, Needham’s men had already made a long march the night before, and Lake’s orders directed them on another long march around to the opposite side of the battlefield. His men worn down and burdened with the army’s 400 baggage wagons, he was unable to make rapid progress. By the time Needham was where he was ordered to be, the enemy ranks on Vinegar Hill had collapsed and their army had already slipped away.

British losses at Vinegar Hill were small. In the fighting on June 21 two officers and 18 enlisted men were killed, 16 officers and 63 enlisted men were wounded, and six enlisted men were missing, for a total of 105 casualties. Most of the losses were among Johnston’s men who were fighting in the streets of the town. Roughly one-fifth of the casualties were among the Irish regiments or the yeomanry. An anonymous officer of the militia wrote, “I have almost lost my hearing, but am content when the good old cause triumphs.”

Among the insurgent ranks on Vinegar Hill, “the carnage was dreadful,” wrote Lake. “The rascals made a tolerable good fight of it.” Losses among the Irish forces are unknown but ran to as many as a thousand. One account stated that 85 dead were found slain by grapeshot in the small section of trenches swept by Loftus’s six guns. An unknown number of women were found among the dead on Vinegar Hill.

Hundreds of the dead had been chased down and slain in the countryside by the royal forces after the battle. Thomas Cloney saw the wreckage of the defeated army and its civilian dependents. “The dead and dying were scattered promiscuously in fields, in dykes, or in the roads, or wherever chance had directed their last steps.” Strewn on the roads were “horses with their necks broken, and their carts, with women and children under them, either dead or dying in the roads or in the ditches, where, in their precipitate flight, they had been upset.”

The rebels’ lack of cavalry left them particularly vulnerable to attacks from the yeomanry and regular cavalry. Avenging the deaths in their own units and from the Protestant and loyalist population, the yeomen unleashed savage reprisals after Vinegar Hill. Anyone who was caught in “coloured clothes,” as civilian attire was known then, might well be shot or sabered immediately. Scores of loyalists were cut down, their claims of fidelity not being believed.

Accounts put heavy blame for postbattle atrocities on the “Hessians” of Hompesch’s Mounted Rifles, a unit recruited from the German states. A Doctor Hill, a local loyalist, had been arrested with his two brothers by the rebels. They took advantage of the confusion after the collapse of the position on Vinegar Hill to escape. Running toward the British troops, the first they encountered were the Germans. Three of the cavalrymen pointed pistols at the heads of Hill and his brothers. Their lives were saved accidentally by a pikeman, who came within sight of the horsemen and ran. The Germans rode after the pikeman and left the Hill brothers, who escaped.

As the royal forces secured Enniscorthy, William Barker was carried to his house. His life was saved because several English staff officers took over his house for their quarters and protected him as looting and retaliation gripped the town. An army surgeon amputated his arm and tended him for a time.

Few captured rebels were as fortunate as Barker. A house turned into a hospital by the rebels was set afire, perhaps killing numerous patients. One witness stated that the fire was accidental, being started by Hessian troops who were shooting the wounded. Wadding from their muskets set fire to the hospital bedding and spread through the building.

With most of the rebels escaping, their defeat at Vinegar Hill was not a final blow in itself. But, it was the last time the Irish army of 1798 fought a major battle. All of their artillery was lost, as were many of their muskets. After some smaller battles and skirmishes, the remnants of their army broke up. Some men tried to make it to the central counties and continue the war, while others opted to stay in Wexford and carry on a guerrilla campaign. Staying at what was thought to be a safe house, Father Murphy was arrested on July 2. He was court-martialed and executed on the same day.

When the French finally arrived in Ireland, it was too late. General Jean Joseph Amable Humbert landed on the western coast at Killala Bay in County Mayo on August 23. Instead of the 14,000-man army that was gathered for the failed 1796 landings, Humbert had only about 1,000 men.

Humbert’s small army did attract some Irish recruits. On August 27, they had a brief flush of success when they defeated a larger force under General Lake at Castlebar. Lake was routed so badly that the affair was called “the Castlebar Races.”

Even after the victory at Castlebar, the disaster at Vinegar Hill ensured that no substantial Irish reinforcements were available. A large British force under Lord Cornwallis was sent after Humbert. On September 8, after losing the Battle of Ballinamuck in County Longford, Humbert surrendered. The French soldiers were treated as prisoners of war, but the captured Irish rebels were executed.

A final French force of 3,000 men sailed on September 17. With them was Wolfe Tone, one of the most charismatic leaders of the United Irishmen. The entire French fleet was captured, ending the last attempt at aiding the 1798 rebellion. Tone died in prison one week after he cut his own throat. Small-scale guerrilla actions continued for some time, but the capture of the French invasion forces and the death of Tone meant the rebellion was finished, militarily and politically.

Immediately after the battle, captive rebels were considered traitors instead of prisoners of war, and faced summary court-martials. Lake wrote to Lord Castlereagh, the acting chief secretary for Ireland, “I really feel most severely being obliged to order so many men out of the world; but I am convinced, if severe and many examples are not made, the rebellion cannot be put a stop to.”

Even showing leniency to loyalists during the uprising was a fatal decision. Military courts held that anyone who stopped the execution of a loyalist prisoner was involved enough with the rebels to be guilty of treason. Bagenal Harvey and Philip Roche were among those executed despite testimony that they had intervened to save lives.

As the Crown regained control of Ireland, the regular army under Lord Charles Cornwallis clamped down on the savage reprisals carried out by the yeomanry and militia. Sir John Moore was so disgusted by their excesses that he famously said, “If I were an Irishman, I would be a rebel.”

Under British pressure, the Irish Parliament passed an amnesty bill for participants in the rebellion on July 20. Conspirators arrested before May 23, and those accused of murder, were barred from amnesty. The assizes took over trials from the military. Slightly more than 1,000 cases came to trial in the civil courts between May and November. One third of the prisoners received the death penalty, although a quarter of these sentences were commuted. Smaller numbers were jailed or flogged, and some were acquitted. The rest were exiled to Australia.

In Australia, several hundred Irish convicts clashed with the government in what was called the Castle Hill Rebellion in 1804. These convict rebels, many of whom were exiled for taking part in the Rebellion of 1798, were captured at Rouse Hill in New South Wales. Such a large number of convicts involved had been transported after the 1798 uprising that the final clash was called “the Second Battle of Vinegar Hill.”

The British never found Byrne. He made his way to Dublin, where he lived until the collapse of an attempted rebellion led by Robert Emmett in 1803. Escaping to France, Byrne joined the French Army and became an officer in the Irish Brigade in the army of Napoleon I. He later met his old comrade William Barker in France. Barker’s brother, a man of considerable influence, won him a temporary release from jail on account of his health. With his wife and a few relatives, the freed prisoner slipped onto a ship bound for Hamburg. From there, he made his way to France and obtained a new commission in the French Army.

For the Irish Rebellion of 1798, no complete count exists for the number of dead. Combining rebel combat deaths, and far more rebel sympathizers and loyalist civilians fatally trapped in the cycle of killings, reprisals, and executions, the death toll in Wexford may have exceeded 30,000. As late as 1801, Anthony Sinnot noted that the southern slope of Vinegar Hill was “for some yards covered with the bones of men and animals, which are bleached as white as ivory by the weather.” Three bodies of executed rebels still swung from a gibbet atop the summit. As if the macabre sight was not a galling enough reminder for rebel sympathizers, loyalists occasionally fired their muskets at the iron cages holding the skeletons of the martyrs.

The Battle of Vinegar Hill, and the blood-spattered war from which it arose, left a complicated legacy. As a result of the Rebellion of 1798, the British pushed through the Act of Union. Taking effect on January 1, 1801, the act changed Ireland from a separate country under British rule into a part of the United Kingdom. Ireland’s parliament was abolished, and the island was represented by members of the Houses of Parliament in Westminster. The United Irishmen were eliminated as a political influence. Hope for an independent and egalitarian Ireland, based on the principles of the Enlightenment, vanished. Religiously motivated killings and reprisals left a lasting bitterness and served to drive Ireland’s Protestants away from supporting independence to a firm adherence to the Crown. It would be more than a century before the dream of independence for Ireland was realized with the founding of the Irish Free State in 1922.

The second last illustration does not show British soldiers summarily executing rebels. This illustration shows the hilltop before the battle and those being executed are loyalists. The Irish harp flag is still flying in the background, so the soldiers are rebels.

Treason was not regarded well by the British in the 18th century and the excesses after the Jacobite Rebellion in Scotland, 52 years earlier, were similar to those after Vinegar Hill. The wearing of tartan was banned, except for those who joined the Highland Regiments of the British Army. Some of the Jacobites captured at Culloden were taken to London and hung, drawn and quartered, in the same manner as William Wallace in the 14th century. The last Irishman who was sentenced to be hung, drawn and quartered had his sentence commuted to a jail term, as the practice was finally considered barbaric. That was in 1902! The gentleman in question had served on the Boer side in the South African War.