By Pedro Garcia

The victory at Manassas on July 21, 1861, had made the Rebels overconfident bordering on lethargic. As one observer noted, “It created a paralysis of enterprise that was more damaging than disaster was for the North.” Conversely, in the artificial quiet following the Union defeat, U.S. naval strategists, moving along unexplored paths toward a new and more effective blockade, undertook a series of major combined operations that swept nearly the entire Atlantic Seaboard from Virginia to the Carolinas, Georgia to Florida. Yet the applause over these successes quickly became muted when Rear Admiral Samuel DuPont failed to take the major ports of Savannah and Charleston. New Orleans, the “Queen City” of southern commerce, was the first important Confederate port to fall to combined operations.

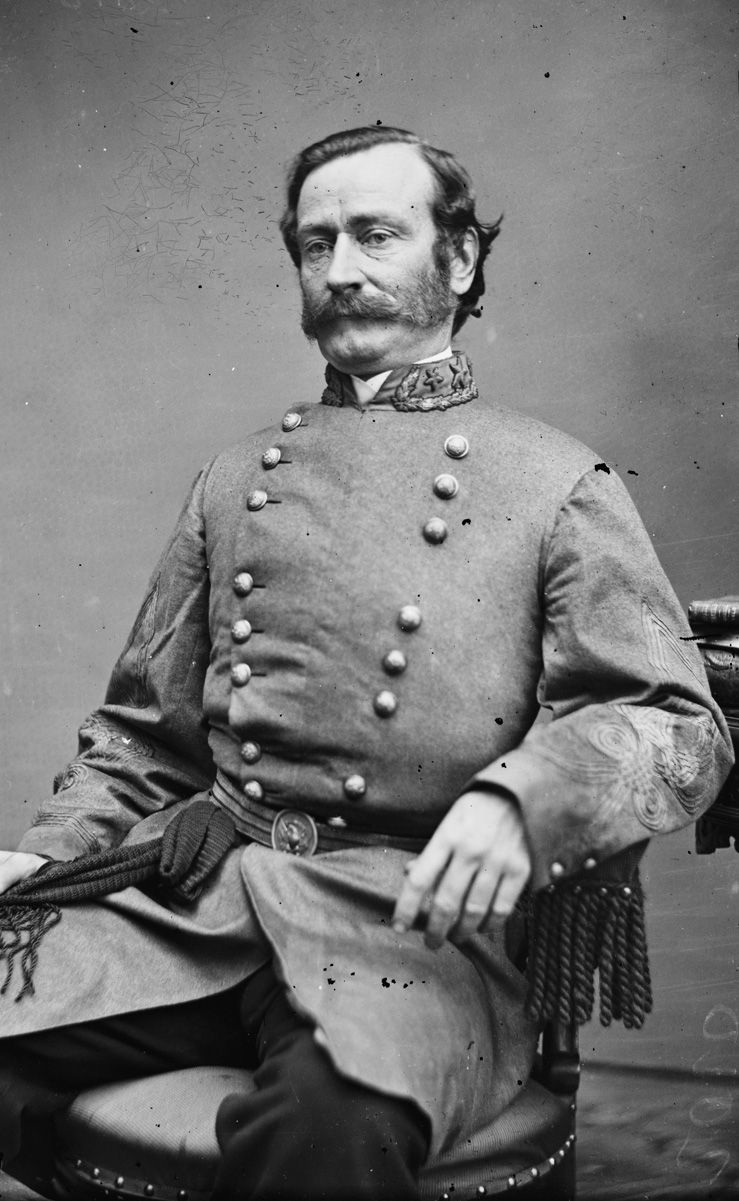

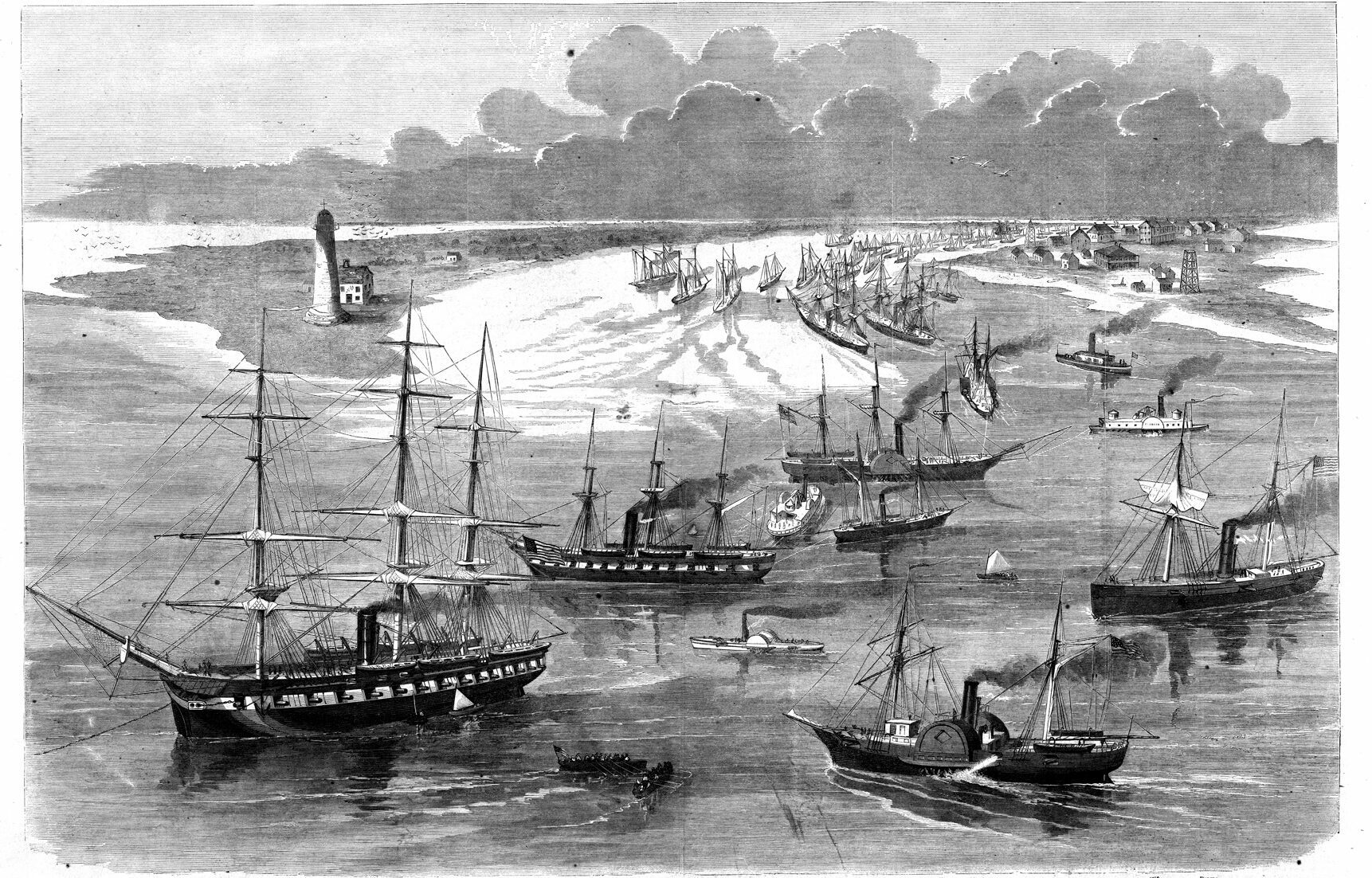

The stage was set for the capture of this vibrant commercial artery when the Blockade Strategy Board selected Ship Island in the Gulf of Mexico as a site for a naval base. The U.S. Navy chose this narrow, sandy, and barren spit of land, barely a mile wide and eight miles long, because it was an ideal location for maintaining the ships of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron and provided a staging area to embark an advance on the “doorway to vitals of the Confederacy.” In September 1861, the small Confederate garrison evacuated Ship Island just as the USS Massachusetts was preparing to shell it. Shortly after the evacuation, Governor Thomas Moore of Louisiana wrote to Confederate President Jefferson Davis, urging him to send an officer to New Orleans who, “with youth, energy, and military ability, might infuse some activity in our preparations, and confidence in our people.” Davis sent Brig. Gen. Mansfield Lovell, a former New York City deputy streets commissioner, to take charge of the city’s defenses.

Although the U.S. Naval Office had developed and designed broad plans for the capture of New Orleans, nothing had gone beyond the discussion stage. This changed when Lieutenant David Dixon Porter of the USS Powhatan managed to get an audience with Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, along with two senators from the Naval Committee, and proposed a bold plan to run past Forts Jackson and St. Philip with fast steamers accompanied by 20,000 troops to seize and hold the city.

But what piqued everyone’s interest was Porter’s innovative scheme to employ a flotilla of specially converted schooners, each mounting a 13-inch mortar to soften up the forts, unhinge their fire, and demoralize the garrisons. He believed a 48-hour bombardment would do the job before the main fleet’s dash up to the city. Welles was impressed, and with Porter in tow, went to see President Lincoln. After deeming the plan plausible, Lincoln said, “We can push on to Vicksburg and open the river all the way along.” The president, who believed that the Mississippi River—and New Orleans in particular—was the key to the rebellion, suggested they see Maj. Gen. George McClellan about the troops. McClellan, who was in the process of conceiving his Urbana plan, was concerned about diluting his own manpower and was reluctant to support the plan. Ultimately, he came around because it was determined that fewer troops would be needed. He found in the scheme the perfect opportunity to bury a man he despised—the insufferable politician Maj. Gen. Ben Butler—in the most remote post possible.

The participation of the U.S. Army in the operation was essential since the city would not fall to an unsupported naval attack. Running the gauntlet of the forts was a calculated risk, for without their reduction the enemy would be left in the U.S. Navy’s rear. The operation ultimately was done based on the certainty that Butler’s 15,000 soldiers could and did isolate and cut off Forts Jackson and St. Philip from the city. Because of his confident boast that he could reduce the forts within 48 hours, Porter was given the mortar flotilla.

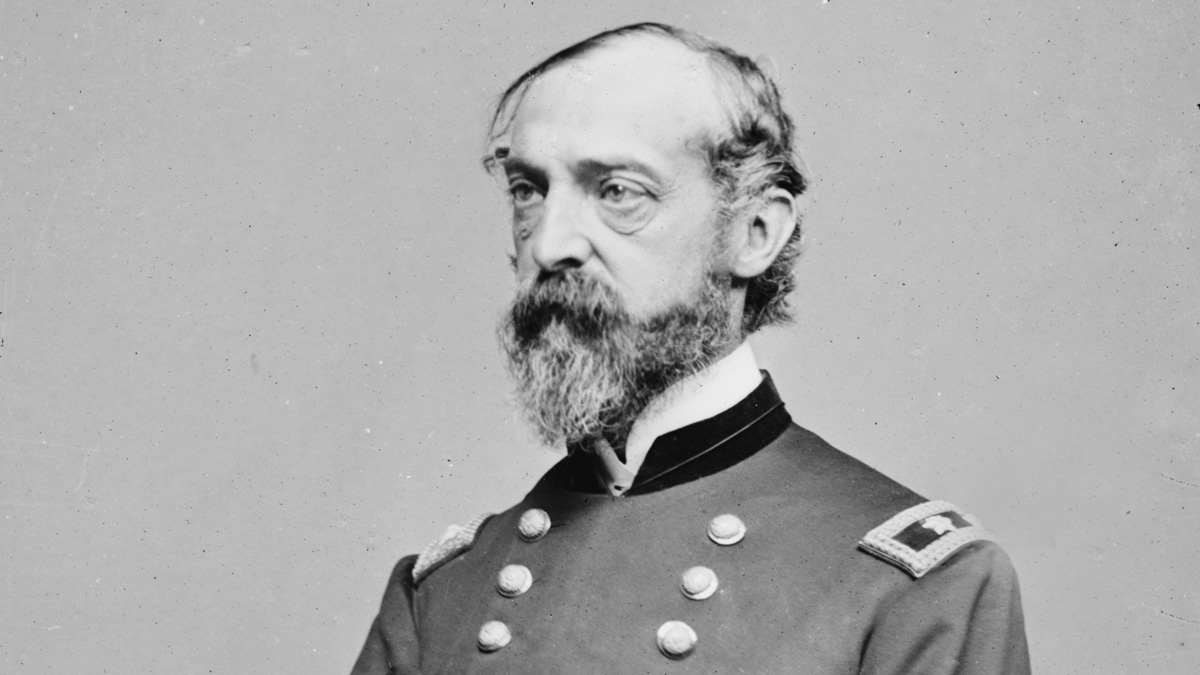

Command of the expedition went to Number 38 on the captains list, David Glasgow Farragut. He was on record as having plans to capture forts with ships and understood the limitations of land fortifications. Welles was impressed that Farragut had severed his Southern roots. Farragut was a Tennessee native, his wife was from Virginia, he had resided in Norfolk, had a brother in New Orleans, a sister in a nearby parish, and a cousin who was married to Captain John Mitchell, the Confederate naval commander at New Orleans. Needless to say, there was much opposition to his appointment, especially in congressional circles. But Farragut came highly recommended by those who had served alongside him in the U.S. Navy.

Realizing that no guarantees came with command, and referring to the opinion of other senior officers, Welles wrote, “Most of them, while speaking well of Farragut, doubted if he was equal to the occasion, but yet no one would name the man for a great and active campaign.” In a navy that traditionally picked its flag officers by seniority, Farragut probably held low expectations, yet he was wholeheartedly Welles’ man.

When Lovell arrived in New Orleans in mid-October, he was appalled at the status of the city’s defense. His predecessor, 71-year-old Maj. Gen. David Twiggs, admitted that the city “was entirely defenseless, that he had been unable to get anything done, and that at many points, [they] could not make an hour’s fight.” Indeed, the best one can say about the septuagenarian is that he met his enlistment quotas. However, the troops raised were principally sent to Florida, Tennessee, and Virginia. On October 18, the day after he arrived in the city, Lovell fired off letters to Davis and Secretary of War Judah Benjamin. To Davis, he wrote, “The city has been almost entirely stripped of everything, should you see in the New Orleans papers that we are well supplied with everything, you may regard it as a ruse. You will always be advised of the true condition of affairs.” To Benjamin, he appealed that the “heads of bureaus be requested to order nothing further from here until we have supplied ourselves with a fair supply for the force required for the defense of the city.”

Lovell probably wondered who was running the war when Benjamin responded, “I cannot restrain the heads of bureaus from purchasing or forwarding supplies from New Orleans.” Thus, the dilution of resources continued. Lovell assiduously applied himself to developing his own resources. He built mills to produce powder and a cartridge manufactory and contracted foundries to cast guns, shot, and shell. He blockaded bayous and inlets that offered avenues of approach and established a network of telegraph and rail links. By the end of December, Lovell had overseen the complete obstruction of the river and had replaced outdated smoothbores in the forts with newly cast Columbiads, seacoast mortars, and a few rifled pieces. Of equal importance, he could claim that 15,000 men, including 6,000 volunteers, were manning the fortified earthworks in and around the city.

But almost as fast as Lovell developed his own resources, trained and recruited men, the myopic Confederate War Department would siphon them off in preparation for the spring offensive in western Tennessee. Having suffered a string of disastrous defeats and reverses, such as the loss of Forts Henry and Donelson and the evacuation of Kentucky and western Tennessee, Davis’ preoccupation was with the defense of this line. Indeed, the Confederates were ruthless in their concentration, and Mansfield Lovell felt an ominous breeze from the Gulf of Mexico.

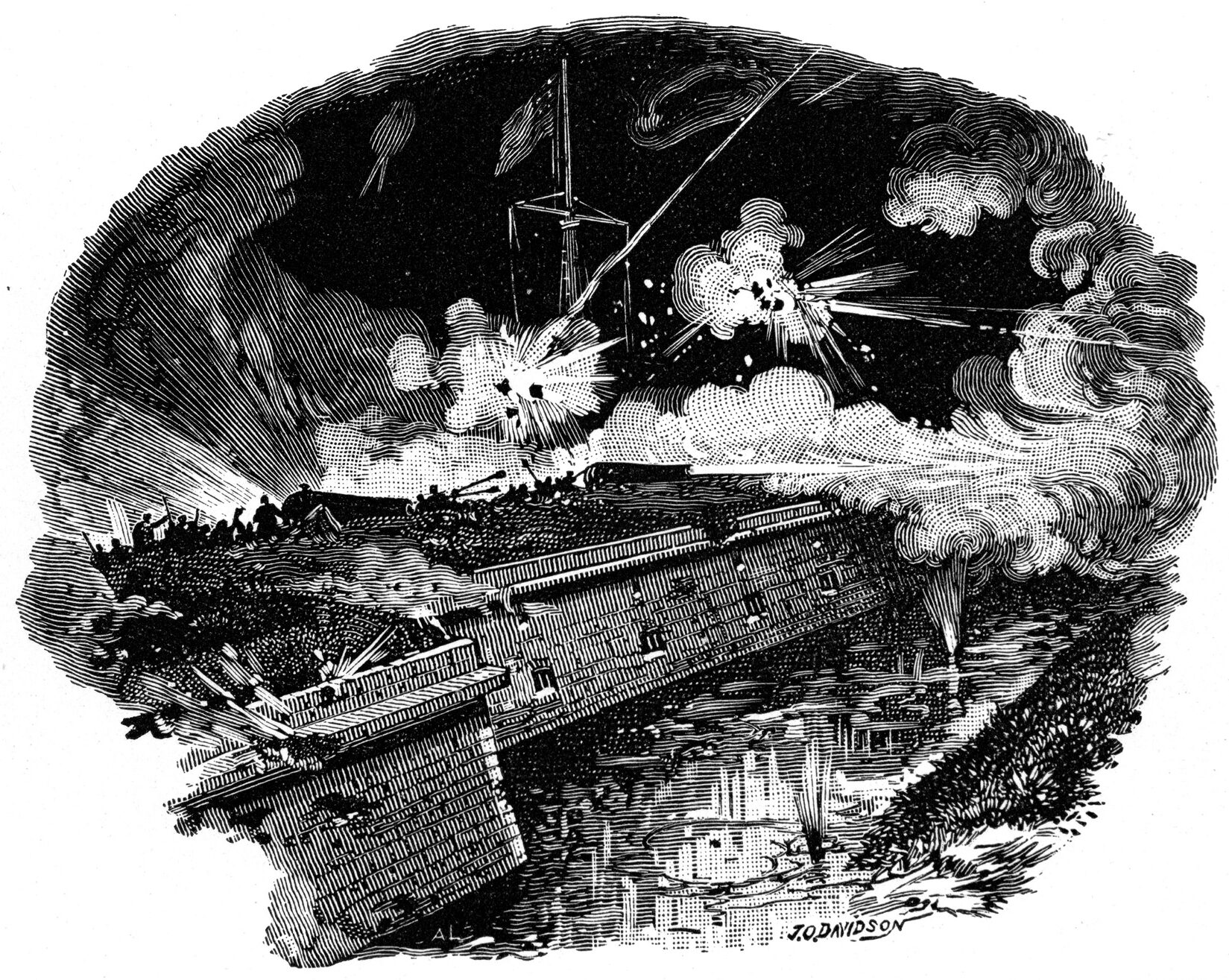

While Confederate generals frequently lacked good maps, this was not the case for Farragut as he planned his attack on the mouth of the Mississippi River. By April 1862, Farragut probably knew as much about Forts Jackson and St. Philip, located 70 miles below New Orleans, as if he had built them himself. He had precise information on these two forts from a lengthy narrative, laid out in elaborate detail, and prepared by Brig. Gen. John Barnard, Chief Engineer of the Army of the Potomac, and forwarded to him by Welles in early February. Barnard had worked with Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard, in the 1840s, rebuilding Fort St. Philip and strengthening Fort Jackson. Farragut learned that “Fort Jackson is a masonry bastioned pentagon with fronts of 110 yards, its walls are 22 feet high, and it is surrounded by wet ditches flanked by 24-pounder howitzers in casemate on each of the ten flanks.” Barnard noted, “Two curtains bearing on the river are casemated for 8 guns each and parapets on the two water fronts are arranged to receive 22 channel-bearing guns with a flanking water battery.”

The fort, built in 1822 at the behest of General Andrew Jackson, hero of the Battle of New Orleans, had settled in the Mississippi Delta mud over the years and the parade ground sometimes held more than a foot of water. Magazines needed pumping day and night and, as a result, the bomb-proof casemated guns came just to the top of the levee and could not be depressed for critical hits at a ship’s waterline, which proved to be absolutely key to the fleet’s passage. Commander John Bartlett of the USS Brooklyn said of his ship’s passage during the ensuing battle, “For 20 minutes we stood silent beside our guns, with shot and shell passing over us and bursting everywhere in the air.” Lieutenant George Perkins of the gunboat USS Cayuga said, “I soon saw that the guns of the forts were all aimed for mid-stream, so I steered close to the walls, and although our masts and rigging were badly cut up, our hull was but little damaged.”

What was important to Farragut, amid all the minutiae, was that the fort was arranged for 126 heavy guns, 115 which bore on the river, which at that point was 700 yards wide. Farragut learned that the smaller Fort St. Philip, located 750 yards diagonally upriver on the east bank, was an irregular quadrilateral work of 150 by 100 yards, arranged to receive “20 heavy guns bearing directly upon the channel with two external batteries mounting 52 guns.” Its parapets were 20 feet thick and rose 17 feet from the bottom of a moat and had the advantage of delivering enfilade fire to any fleet coming upriver. Indeed, this antiquated Spanish work had withstood a nine-day bombardment and repulsed a British fleet in 1815.

The forts were located on a section of the Mississippi known as Plaqueminds Bend, or Windless Bend, for sailing ships coming up the river had to tack against a four-knot current to negotiate the bend, thus making them sitting ducks for the forts, a situation rendered moot by Farragut’s steam-powered fleet. Just below Fort Jackson was a river obstruction consisting of eight dismasted schooners, strongly moored and chained together, with their ground tackle and rigging dragging in the river. Behind this were 18 fire rafts that were to be released intermittently to light up the area and harass Farragut in his preparations. This job was tasked to the polyglot Confederate forces afloat, who would completely botch the operation. “Although certainly dangerous, they were so badly managed that in a little while they merely served to amuse us,” recalled a Union tar. Indeed, although ordered to, they neglected to send any rafts down the river the crucial night before Farragut ran the gauntlet. Because of this criminal neglect, the river remained in total darkness while he made his final deployment. Mitchell “had failed to ignite and send down all the fire-rafts that were under his charge, at the proper time to meet our fleet,” wrote Porter. “It can well be imagined what the effect of millions of burning pine-knots on 20 or 30 rafts would have been.”

Farragut digested this information, as well as Barnard’s opinions and suggestions, and gleaned information from fishermen concerning the river obstruction and the motley naval complement. From New Orleans newspapers he accurately gauged the despairing state of morale. But before launching his attack, he was to have more precise information. A U.S. Coast Survey team mapped and plotted with triangulated precision the range of Confederate guns and guided Porter’s mortar schooners into position. Porter test-fired his mortars and dressed the tops of his masts with bushes, so they could blend in with the trees on the banks.

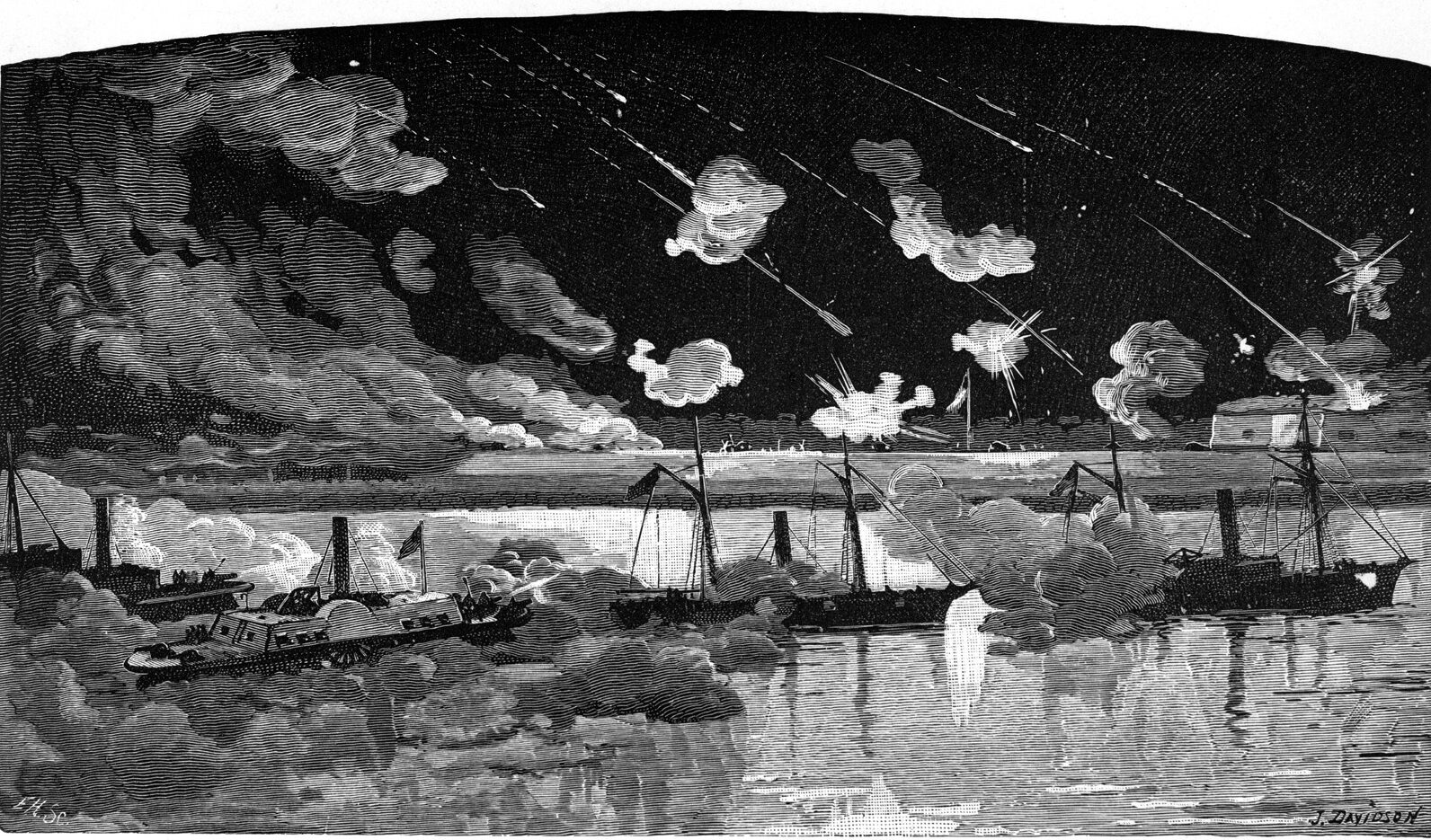

By April 18, Porter’s 21 bomb boats grouped into three divisions were guided into position, the first and third divisions along the south bank of the river, the second on the north bank. They were placed 2,850 to 3,600 yards from the forts. Firing commenced about 9 am, and shortly thereafter Fort Jackson was replying vigorously, but inaccurately. Each schooner fired every 10 minutes for 10 straight hours. After placing the loads, sailors scurried aft as fast and far as possible, standing on tiptoe with their fingers in their ears and mouths open to counteract the concussion. The shells were punishingly accurate, setting fires, threatening magazines, disabling guns, opening the earth, and burying men alive. When firing ceased, the Union sailors discovered that 1,100 shells had found their target or had plopped into the mud before bursting, creating small earthquakes. The mortar flotilla had received relatively little damage because of its camouflage among trees. The deception was so effective that, even with glasses, observers in the forts never spotted the schooners on the south bank.

During the night Porter moved his exposed second division from the north to the south bank. When the Union sailors renewed their bombardment early the next morning, Porter decided to make the effort continuous. Yet ammunition was running low and he slowed each schooner’s fire to one bomb every half hour. Inside Fort Jackson, the bombardment kept men inside the casemates. The parapet and the interior of the fort were honeycombed with sandbags, reinforcing damaged areas and replacing blown-up masonry. Clearly, the forts had suffered, but it was equally clear that there was no sign of surrender. Porter, in a foul temper and painfully aware of his boast that he would reduce the forts within 48 hours, began to despair and lose confidence in taking the forts before Farragut made his run. Indeed, had Porter been present at the interview between Welles and Farragut, he would have been surprised to learn that his foster brother believed the mortar flotilla would be largely ineffective. Farragut said he placed more faith in the horizontal fire of modern guns than he did in the parabola fire of mortars.

Cognizant of dwindling ammunition and coal, Farragut determined on Easter Sunday, April 20, that unless vigorous action was taken, “he would be reduced to the status of a blockading fleet.” That moonless and drizzly night, covered by particularly heavy mortar fire, two gunboats, the USS Itasca and Pinola, were detailed to break the river obstruction and open the channel. “In a moment a sharp fire was opened upon us from the water batteries and Fort Jackson, nearly all the shots passing over us,” wrote Lieutenant George Bacon of the Itasca. It was a near thing, but dawn found a wide breach in the all-important river obstruction.

Once again, “the want of concert of action among the independent floating commands of the enemy caused him to neglect the protection of what should have been his main reliance for defense,” wrote Bartlett. The only cause for delay removed, and over the objections of fleet’s commanders, some of whom deemed it risky to advance upriver beyond the reach of their supplies, Farragut ordered the fleet to prepare to run past the forts.

The running of the forts “must and should be done, even if half the fleet is lost,” wrote Farragut. His blue-water sloops-of-war prepared for brown-water action. They stowed superfluous spars below, rigged splinter nets on the starboard sides, barricaded the helms with sails and hammocks, heaved hempen fenders over the inboard sides, and spread chains and sandbags around the deck machinery. Day and night, mortar shells were lofted into Fort Jackson and to a lesser degree on Fort St. Philip, but by the afternoon of April 22, with Butler’s troops anchored on transports below the fleet, Farragut was growing impatient. He told Porter, “We are wasting ammunition and time. We will fool around down here until we have nothing left to fight with. I’m ready to run those forts now, tonight.”

“Wait one more day and I will cripple them so you can pass with little or no loss of life,” replied Porter. “All right, go at ‘em again and we’ll see what happens by tomorrow,” Farragut said. He also would hope for a change in the northerly wind that would counteract the tide and thus retard the high and powerful current running past the forts.

The man who shouldered the responsibility of creating and directing the South’s naval forces was Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Russell Mallory, an outstanding maritime lawyer and former U.S. senator from Florida, who had chaired the U.S. Senate Naval Affairs Committee. Although a gifted and capable administrator, he was handicapped by not having the staff or organization that his counterpart possessed. He was the bearer of an inhuman responsibility, a one-man show who not only had to build a navy from scratch in time of war, but was the author and executor of naval strategy, and he paid dearly for his isolation with some major blunders, not the least of which was the loss of New Orleans.

Mallory’s efforts were characterized by divided naval commands, friction between the army and the navy, and the injudicious use of resources. In the short duration of the crisis, Mallory employed five different naval commanders, all of whom had nebulous parameters of command and all of whom exhibited little cooperation or coordination among themselves, let alone with the army. Asserting that a unified command was the only proper way to defend New Orleans, Lovell had raised the issue of control of the naval units with the authorities in Richmond, but Davis reminded him in a terse message that they were not part of his command. Mallory and the Confederate authorities in Richmond believed that the real threat to New Orleans was not Farragut’s fleet less than 80 miles downstream but Captain Andrew Foote’s ironclad flotilla 500 miles north at Island No. 10. Mallory’s reckless and impractical shipbuilding program was a major blunder that left New Orleans bereft of the resources that would have been better employed at constructing a conventional gunboat force to deal with Farragut.

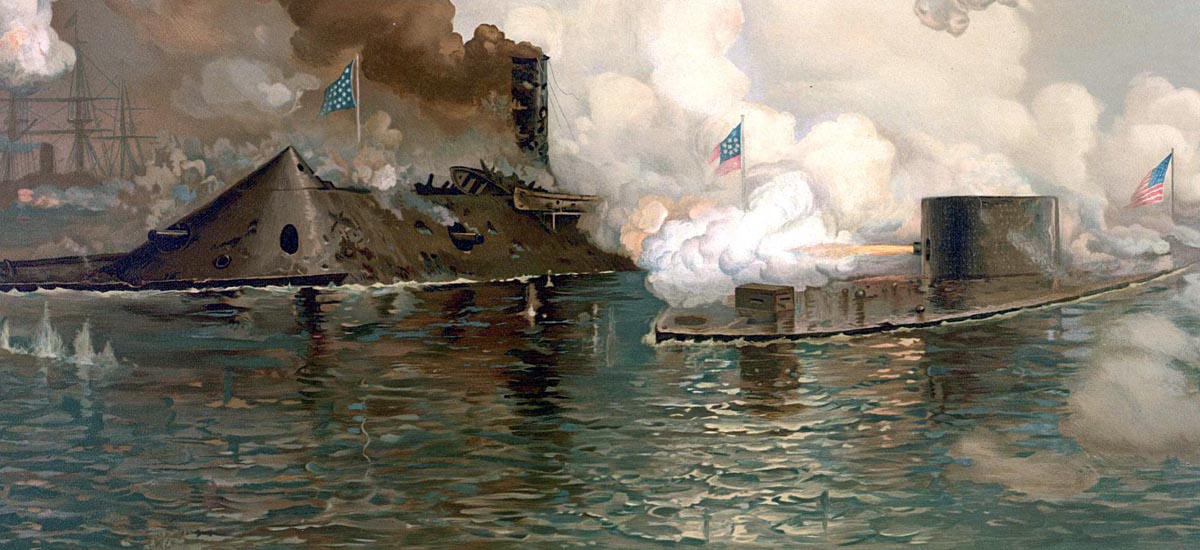

A progressive visionary, Mallory, kept insisting that he would pin his faith on a few ironclads. In September 1861, he contracted for two powerful ironclad rams, the CSS Louisiana and the CSS Mississippi, that he expected to sweep the Union fleet from the river. They were gigantic for the time. The Louisiana was 264 feet long, 62 feet abeam, and was propelled by three screws driven by three engines and 11 boilers that could develop more than 1,500 horsepower, with an unheard speed of 14 knots. Her armor required more than 1,100 tons of railroad iron, and she carried 20 guns, including four rifled pieces. The Mississippi was 250 feet long, 58 feet abeam, and was also driven by three screws. She carried 16 guns, including two rifled pieces.

Work on the bulky behemoths, which did not begin until October, was characterized by shortages and delays in the delivery of timber and railroad iron, as well as a week-long carpenters’ strike. They were the products of wishful thinking, experimental technology combined with house-building techniques. They would prove to be sloths in the water, poorly designed and underpowered. Considering the South’s limited resources, they should not have been built and, in fact, neither vessel was completed. The Louisiana was launched without her engines and proved to be no better than a floating battery as she lay off Fort St. Philip. The Mississippi was two weeks from completion by the time Farragut entered the river and was scuttled on April 25 to prevent her capture. If the Louisiana had been capable of operating under her own power with a speed comparable to Farragut’s ships, it is likely she could have done considerable damage to Farragut’s fleet. As for the Mississippi, Farragut deemed her “a magnificent specimen” and said that if she had been seaworthy she would have operated against his wooden ships “like a bull in a china shop.”

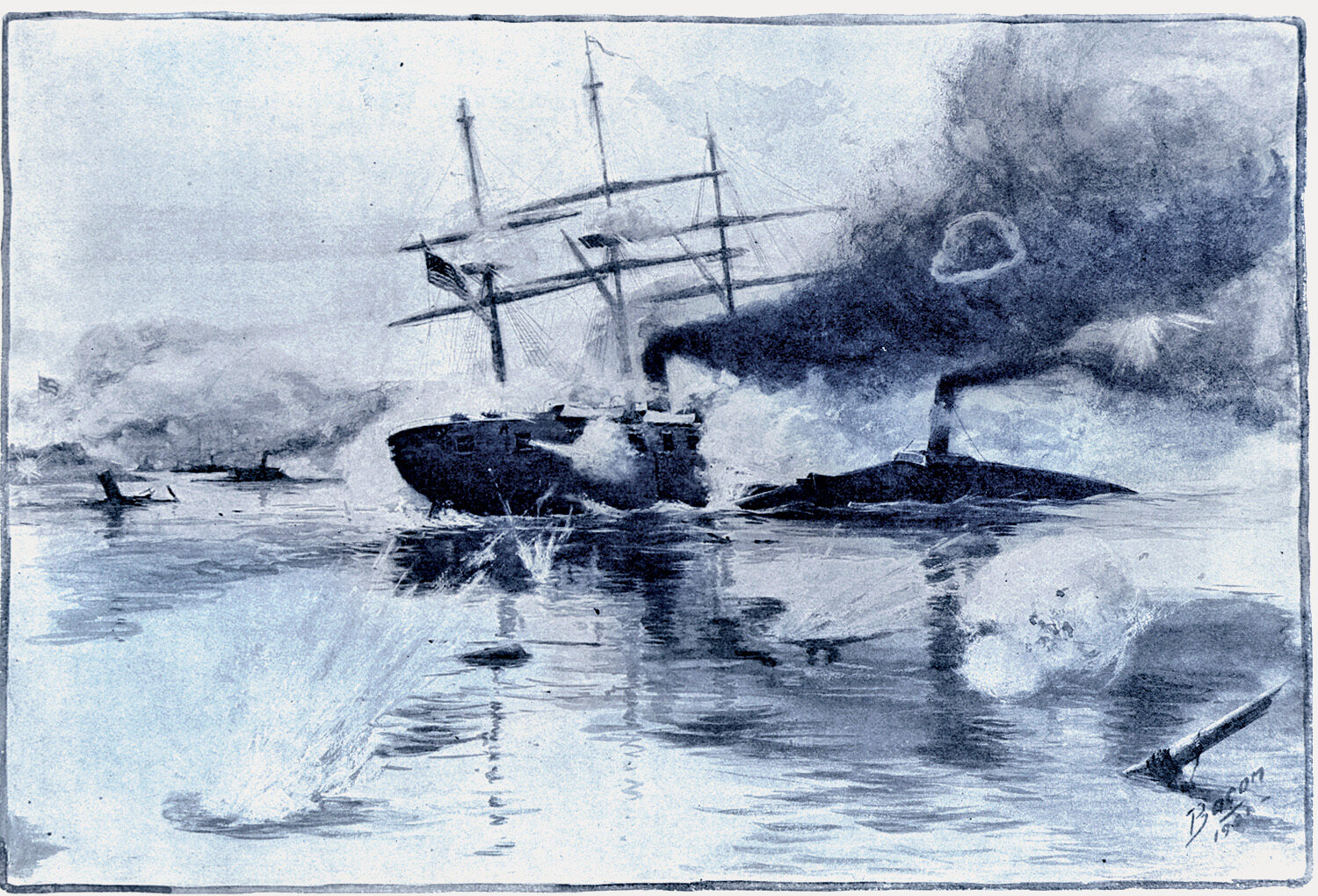

In addition to the Louisiana, the ragtag flotilla led by Mitchell included the 143-foot, ironclad ram CSS Manassas. She had been converted from a powerful tugboat and originally placed in privateer service in September 1861. She attacked and broke up a Union blockading force at the Battle of the Head of Passes on October 12, 1861. The ironclad ram subsequently was purchased by the Confederate government in December. Confederate naval forces were rounded out by two gunboats and two steam launches, each fitted with a small howitzer, and a half dozen tugs and unarmed vessels.

Mitchell also retained an anomalous control over a pair of gunboats that were commissioned by the State of Louisiana. To complete the three fleets, there were the five gunboat-rams of the notorious and independently commanded River Defense Fleet. Indeed, when Mitchell sent Captain John A. Stephenson orders from Lovell placing him at Mitchell’s disposal, the captain, while pledging cooperation, replied he would take no orders from him, or any other naval officer. Distressed, discombobulated, and apoplectic, Mitchell then washed his hands of them; and, as could be foreseen, they were useless. “Not one of them made the feeblest offensive or defensive movement,” he wrote.

Farragut’s extreme confidence was rooted in his fleet’s awesome firepower, 17 seagoing warships, 43 vessels in all, carrying 245 guns. This gave Farragut an eight-to-one advantage over the Confederates. Even with the guns in the forts, and with those of the water batteries, the Confederates would fight at a three-to-one disadvantage. “One fact only was in our favor, and that was the division of their forces under three heads prevented unanimity of action,” Porter said.

The lone major Confederate success was achieved by the Louisiana State gunboat, Governor Moore, commanded by the gallant and dashing Beverly Kennon, late of the Confederate Navy and the U.S. Navy. In a dramatically fierce and pitched battle, she succeeded in ramming and sinking the seagoing gunboat USS Varuna. Soon afterward, almost shot to pieces, ablaze, and with more than two thirds her crew dead, she was scuttled. Manassas fought heroically and succeeded in delivering timber-shattering blows to two of Farragut’s larger warships, the Brooklyn and USS Mississippi. But because of her sluggishness, the ram was selected as a target by any enemy within sight, and subjected to a withering fire, coming to grief two hours after entering the fight.

To crown the drama of the Louisiana, sailors were lacking. They were substituted by volunteer soldiers from the army who had no naval training and, for the most part, no artillery experience. This would prove quite damaging. “A 9-inch shell fired by the Louisiana struck the Brooklyn about a foot above the waterline, on the starboard side of the cutwater, forced its way for three feet through the timbers and remained there,” wrote Bartlett. “At New Orleans, the shot was cut out, and it was found that in their hurry the gunners had neglected to remove the lead patch from the fuse, so that the shell did not explode. Had it done so it would’ve blown the whole bow off, and the Brooklyn would’ve been sent to the bottom.”

Indeed, while the ram received many a fierce broadside from several Union ships that had no effect whatsoever, her shells pierced their sides as if they were paper maché. “For among all the ships that were sent to Farragut there was not one whose sides could resist a 12-pound shot,” wrote Porter. Yet, enemy vessels were able to withdraw, sheer off, and move on, while the Louisiana, immovable as she was, could not press the issue.

About midnight on the April 24, the Federal fleet began to stir and make final preparations for battle. The running of the gauntlet would be conducted in three divisions that were expected to divide the enemy’s fire. Leading the way would be eight gunboats and warships passing on the eastern side of the river, fixing their fire on Fort St. Philip. The Center Division of three warships, with Farragut’s flagship, the USS Hartford in the lead, were to engage Fort Jackson on the left, followed by the Third Division of six gunboats, whose objective was also Fort Jackson.

At 1:55 am two red lanterns displayed at the yardarm of the Hartford gave the signal for action, and by 3:30 am the long single column of warships had advanced into the still, hazy night and into a suffocating cauldron of fury. Almost immediately, the water battery off Fort Jackson detected black shapeless masses moving upriver and barked in protest, joined shortly by the guns of the forts. It is difficult to conceive or aptly describe the grandeur and horror that followed. A Confederate observed, “The Federal vessels replied with their broadsides, the flashes of the guns from both sides lit up the river with a lurid light that revealed the Federal steamers. I do not believe there was ever a grander spectacle witnessed than that displayed during the great artillery duel that followed.” A Union sailor added, “Combine all that you’ve heard about thunder with all that you’ve heard of lightning, and you have a fair idea of the Battle at Plaqueminds Bend.”

Kennon of the Governor Moore noted that the naval action occurred in a tight space. “The bursting of every description of shells quickly following their discharge, increased a hundred-fold the terrific noise and fearfully grand and magnificent pyrotechnic display which centered in a space no more than 1200 yards in width,” he wrote. By the flash of guns, for an instant seamen saw half-naked gunners at the forts rushing, shouting, and screaming. Boldly moving up to the hulk line, the mortar flotilla delivered its most furious bombardment. The First Division did not emerge from the action unscathed; as previously noted, the gunboat Varuna was sunk by Kennon’s cottonclad. The Center Division, carrying the fleet’s heaviest broadsides, passed with various fortune. The Hartford was seriously damaged by artillery fire and barely survived an encounter with a fire raft. In trying to avoid contact with the fire raft, the flagship ran aground and was unable to escape as the fire raft was again pushed against her sides. She was set ablaze, and only the prompt and heroic efforts of her crew saved her from destruction. The flagship was at last extricated and continued her way up the river. Finally, three of the six gunboats of the Third Division, caught under the guns of the forts in the emerging daylight, failed to pass and fell back down the river.

“Day was getting broader and with the first ray of the sun we saw the fleet above us, and a splendid sight it was, or rather would have been under different circumstances, and the Uncle Sam of my earlier days had the key to the valley of the Mississippi in his breeches pocket, for which he had to thank his gallant navy and the stupidity, tardiness, ignorance and neglect of the authorities in Richmond,” wrote a Union tar.

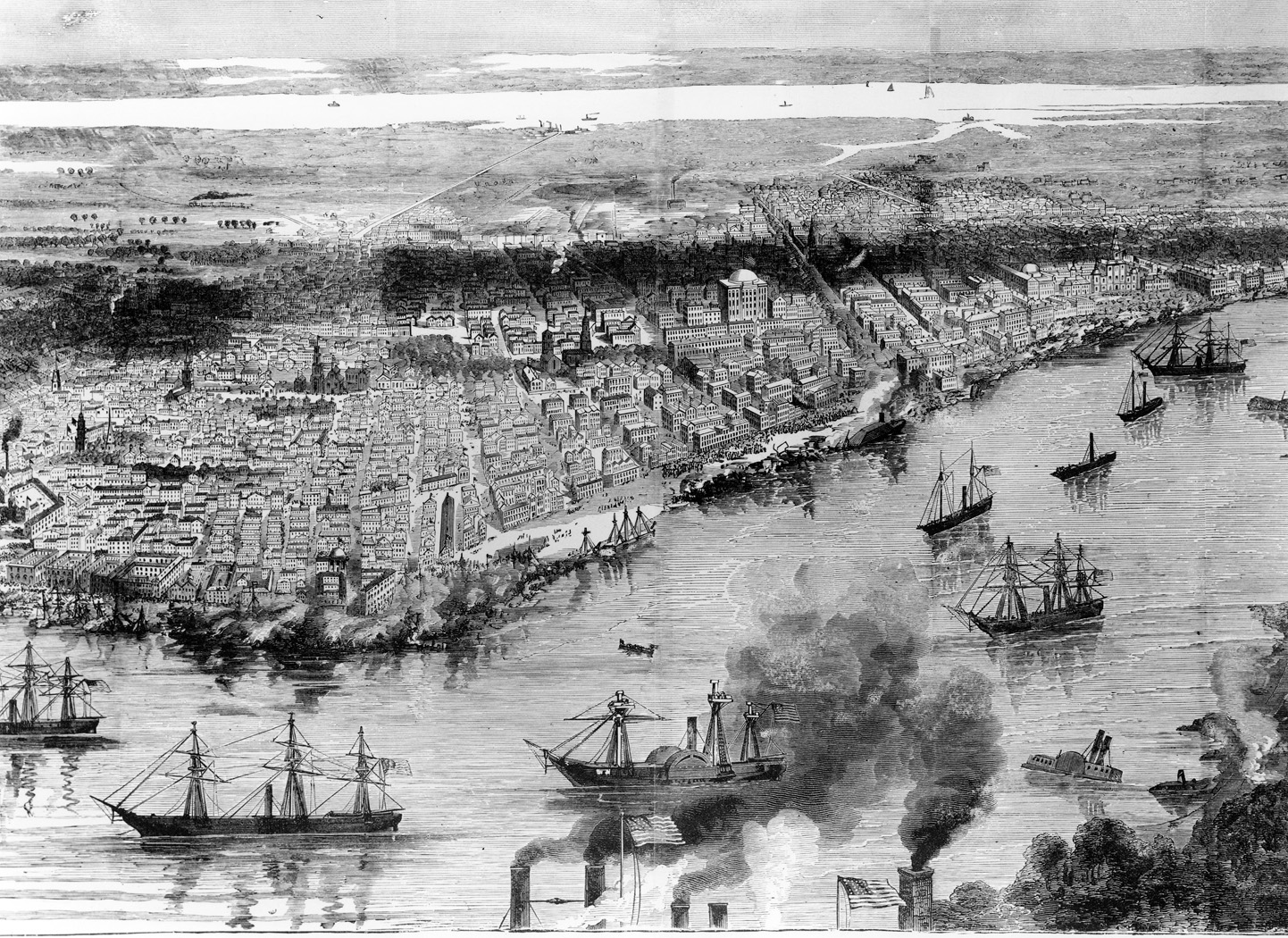

Dawn creased the horizon on 13 of 17 vessels at anchor, the fleet having taken 184 casualties, and by 11 am the next day were headed for New Orleans. Butler’s command moved to invest Fort St. Philip, while Porter continued his bombardment of Fort Jackson. The citizens of New Orleans were in total panic. Lovell, with the city council’s endorsement, and being necessarily reduced to a force of 3,000 militia, evacuated the city and torched the levees.

After making short work of a valiant but benign resistance at Chalmette, four miles below the Queen City and the scene of Andrew Jackson’s glory, Farragut’s bruised fleet hove in sight, training its guns on the raging, amorphous mobs. What followed was much defiant posturing, and the city refused to submit to Union authority. A Union flag, flying over the former U.S. mint, was torn down and destroyed by the mob.

Farragut’s patience was sorely tested, but he did not destroy the city in response. He wisely let the city exhaust its anger, and instead moved upriver to destroy fortifications at Carrollton. When he reopened negotiations on April 28, he reminded the mayor, “Fire from this fleet may be drawn upon the city at any moment … and the levee would, in all probability, be cut by shells.” The city surrendered the next day.

On May 1, Butler arrived in New Orleans to begin an uneasy military occupation that was characterized as much by angry controversy as it was iron-hand despotism, bringing much embarrassment to the Lincoln administration, and compelling his recall in December.

The forts had sustained only 48 casualties during the battle and twice refused Porter’s demand for surrender, but when rumors of the surrender of the city reached Fort Jackson, a reaction began to permeate the garrison. Hoping to reassure the men who were “still obedient but not buoyant and cheerful,” Brig. Gen. Johnson K. Duncan, commander of the two forts, issued an order on April 27 praising their “courage, gallantry, and heroism.” The garrison was mostly made up of Germans, who were distrusted from the start. They were also told that Duncan intended to blow up the fort over their heads rather than surrender. The balance of the garrison was made up of impressed Northerners. In fact, one week earlier one of Porter’s boats had picked up a red-capped deserter who claimed to be an impressed Pennsylvanian. “The Northern men had applied for duty in the forts to avoid suspicion, and in the hope that they would not be called upon to fight against the Federal Government,’’ wrote Duncan.

Hence, at midnight they mutinied, spiking guns, dismounting others, loudly demanding surrender, even threatening the lives of their officers. The post chaplain tried in vain to quell the mutineers, and Duncan had no choice but to send a flag of truce to Porter the next morning. “The officers suggested that the mutiny of the troops was caused by many of them being foreigners or northerners,” wrote a Union observer. After the surrender, the fort was inspected by Coast Survey officers, who found a scene of desolation and ruin. The infrastructure was completely shattered, gun carriages were destroyed or damaged, but most of the dismounted guns were remounted and, as Farragut’s fleet could testify, the ability of the fort to fire had not been impaired. “We are just as capable today of repelling the enemy as we were before the bombardment,” Duncan later wrote. Perhaps the effect of Porter’s bombardment was best summed up by Maj. Gen. Godfrey Wietzel of the U.S. Corps of Engineers: “To the uninitiated, it seems as if this work was badly cut up,” he wrote. “It is as strong today as when the first shot was fired at it.” Nevertheless, the bombardment prepared the forts for the fleet’s passage and kept the enemy gunners under cover and away from their openly mounted guns.

The loss of New Orleans resonated profoundly throughout the South. Mallory was affected quite bitterly, calling the loss the most stunning blow of his lifetime. Two weeks after the fall he wrote to his wife, “I do not know how you discovered that the naval losses on the Mississippi affected me, but the fact is that they almost killed me, and I am ashamed to say that I have lain awake at night with my heart depressed and sore, my eyes filled with tears, in thinking over them. Our boys fought splendidly and merited by their gallantry the victory they had not the force to achieve. This has made me very weak and neutralized the effect of all the medicine I have taken, but I am getting over it.”

But he never did, and the lamentations grew to revolve around an even more freighted proposition: If during the spring of 1862 any battle kept Europe neutral, it was Farragut’s victory. If Farragut had failed, followed a month later by Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s devastating Shenandoah Valley campaign, combined a month later with George McClellan’s embarrassing defeat on the Virginia Peninsula, European intervention looked a good deal more attractive, especially with a good portion of the Union Navy lying at the bottom of the Mississippi River.

The politics of local defense continued to hamstring strategy in the Confederacy. Louisianans, as had the states on the Eastern Seaboard before them, felt Richmond had betrayed them. Moore, joining the cacophony, decried the myopia of the Confederate government and pointedly asked, “How much longer is Louisiana to be considered beneath the considerations of the Government?” Frequently during the crisis, Moore sent requests to Davis for all manner of aid for the defense of the Crescent City. He was looked upon as an alarmist and given half-hearted cooperation. At one time, Davis replied, “Should your worst apprehensions be realized, which I cannot bring myself to believe, when I remember how much has been done for the defense of New Orleans since 1815, both in the construction of works and facilities for transportation, I hope a discriminating public will acquit the Government of having neglected the defenses of your coast and approaches to New Orleans.”

A Virginia newspaper called it “the most deplorable tale ever told.” Although vindicated in a court of inquiry, Davis blamed Lovell for the loss and crucified him ever after. In his memoirs, Davis missed a great opportunity to offer a well-deserved apology. He could have looked back on a country that had elected him to a position of power nearly equal to that of a dictator, where so many cities now lay in rubble, rich farmland and wealthy agrarian economy had been laid to waste, and the infrastructure was destroyed. All was gone. All but New Orleans. Lovell could not have fought for New Orleans without destroying it, and he knew it. New Orleans and the surrounding towns were spared, along with countless lives and millions of dollars in property, thanks to Lovell, a Northerner who fought for the South, and Farragut, a Southerner who fought for the North.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments