By John Walker

For the black-skinned, blue-clad soldiers deployed on the extreme left flank of the Union Army outside Nashville, Tennessee, the order to advance announced at dawn on December 15, 1864, was a long time coming. No unit of the United States Colored Troops (USCT), made up entirely of black enlisted men under the command of white officers, had been committed to major combat in the western theater since the bloody setback at Port Hudson, Louisiana, in May 1863. Now, almost 18 months later, two brigades of untested black troops were about to play a role in one of the most decisive battles of the Civil War.

Four miles south of the city, General John Bell Hood’s ill-fed, ill-clothed, and ill-shod veterans of the Confederate Army of Tennessee waited grimly in their defensive works. This once-proud and formidable force had never been in such dreadful condition. Still reeling from the horrendous physical and psychological trauma it had suffered in the catastrophic defeat at Franklin, Tennessee, two weeks earlier, the army was so thinned, in fact, that it had only managed to extend a line of partially completed works four miles below the city, leaving sizable gaps between both flanks and the Cumberland River.

If the battle-hardened veterans under Hood could achieve victory—an increasingly remote possibility—their stalled offensive into their namesake state could be resurrected. Accustomed to facing heavy odds, the renowned Confederate infantry, if victorious, could drive their defeated foes from Nashville, reclaim the capital city, and gain access to the vast Federal supplies there. With his troops rested and refitted, Hood could then push north, threatening Kentucky and Ohio, his army’s ranks swelling with new recruits along the way. Union Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman might have to abandon his punishing march to the sea through Georgia and return to the defensive.

Threatened with removal from command of the Federal forces in Nashville for refusing to attack Hood immediately, Maj. Gen. George H. “Pap” Thomas nevertheless continued his meticulous preparations not only to defeat the Rebel host in his front but to utterly destroy it. Thomas needed time to organize and deploy his large and heterogeneous forces, find mounts for a third of his 12,000-man cavalry, and gather the necessary transports to conduct a vigorous pursuit of the enemy in the event they were driven back from the outskirts of the city.

It was now December 1. Maj. Gen. John Schofield, the victor of Franklin, was safely inside Nashville with his five divisions, 62 guns, and almost 800 wagons. Other units were arriving daily to fill out Thomas’s army. Hood had few options; he feared wholesale desertion if he retreated to regroup. He could attack Murfreesboro, 30 miles southeast of Nashville, where 9,000 Union troops under Maj. Gen. Lovell Rousseau were posted in strong works, but Thomas could reinforce Rousseau with more troops than Hood had in his whole army. Attacking Nashville, one of the most heavily fortified cities on the American continent, was out of the question. If Hood managed to bypass Nashville and push north, he risked attack from flank and rear.

“The Lines Looked More Like the Skirmish Line of a Regular Army”

When Hood arrived in front of Nashville, he adopted a tactic that Napoleon Bonaparte, the father of modern warfare, once called a form of deferred suicide: the passive defensive. Hood put his men to work putting up breastworks and waited for Thomas to attack him, while he prayed for the arrival of reinforcements. He implored his superiors in Richmond to get General Edmund Kirby Smith to send troops from the Trans-Mississippi Department, but the chances of substantial reinforcements arriving in time to help Hood were remote at best.

As the exhausted Confederate soldiers set about digging trenches and throwing up breastworks south of the city, to one private “the lines looked more like the skirmish line of a regular army, than a regular army itself.” Many of Hood’s veterans had no overcoats or blankets, and their uniforms were in tatters. Those who had shoes—and as many as one in five did not—wrapped their worn boots in rags or gunny sacks. After a fierce storm hit Nashville on December 9, many soldiers began leaving bloody footprints in the snow.

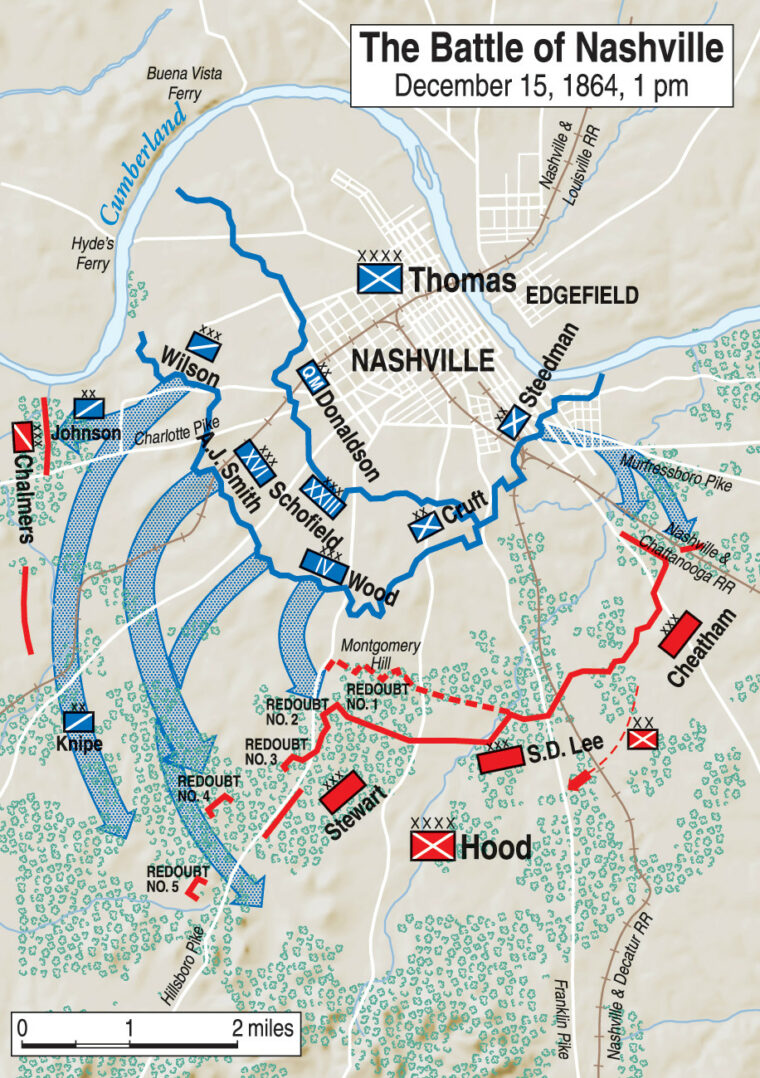

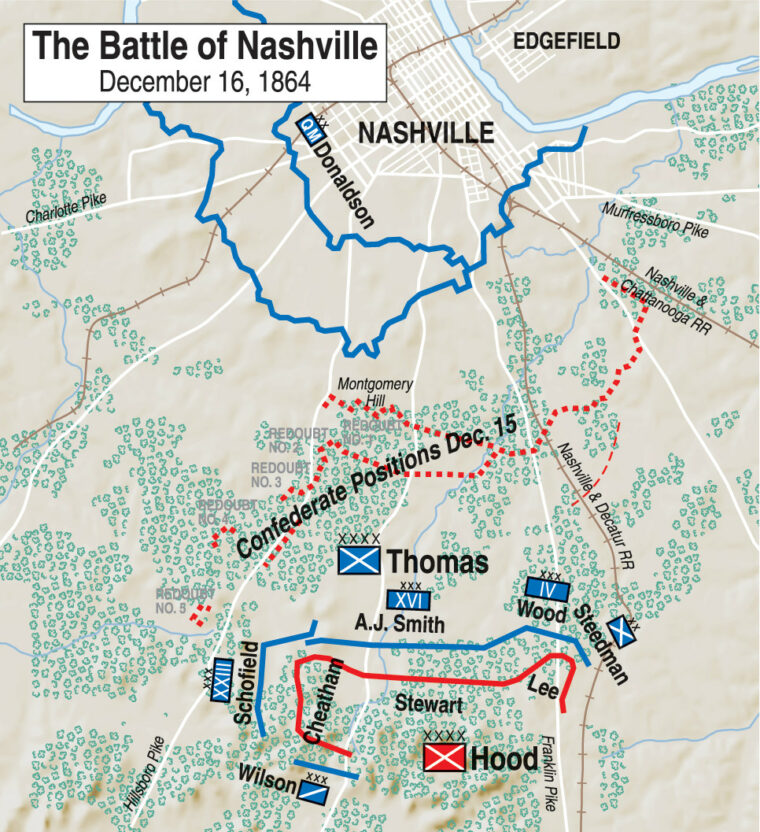

On paper, Hood’s army still looked formidable: three corps, nine divisions, 27 brigades. But after Franklin, the Confederate force in front of Nashville was down to about 23,000 infantry and 1,750 cavalry. Meanwhile, all the Federal units that would take part in the defense of Nashville had arrived safely. Three veteran divisions that made up Maj. Gen. A.J. Smith’s XVI Corps were welcomed when they arrived on November 30 after an arduous trek across Kansas from St. Louis. The garrison and quartermaster troops had now been augmented by militia units, new levees, convalescents, detached units, three corps of infantry from three separate commands, and finally by a provisional detachment under Maj. Gen. James Steedman that included two brigades of U.S. Colored Troops. Upon arrival by rail from Chattanooga, the 1st and 2nd Colored Brigades were assigned positions on Thomas’s extreme left flank along a front that stretched from Fort Negley east to the Lebanon Pike, close to the banks of the Cumberland River.

A “Great Danger in Delay”

Hood’s army had barely arrived when Thomas began receiving an almost daily barrage of telegrams from Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck in Washington and from Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, 500 miles away in City Point, Virginia, urging him to attack and destroy Hood immediately. On December 6, obviously not cognizant of the weakened condition of Hood’s army, Grant wired Thomas: “There is great danger in delay resulting in a campaign back to the Ohio.” He ordered him to attack at once. Thomas agreed, but the difficulties he faced convinced him that his army wasn’t adequately prepared, and he decided to delay until at least December 9 or 10.

Grant, worried that a Rebel thrust toward the Ohio River would embarrass him for allowing Sherman to march away from Hood’s army, decided to relieve Thomas, but then changed his mind. By that time, both armies were literally frozen in place and unable to move, the result of a fierce storm that had covered the ground with a blanket of ice and snow. The storm halted construction of a line of wood-and-earthen forts, or redoubts, that Hood had ordered built along both sides of the Hillsboro Pike to shore up his weak left flank.

On December 9, Halleck wired Thomas that Grant had “experienced much dissatisfaction at your delay in attacking the enemy.” In reply, Thomas told Halleck, “I feel conscious I have done everything in my power, and that the troops could not have been gotten ready before this. If Gen. Grant should order me to be replaced I will submit without a murmur.” Two days later, as the freezing temperatures continued to keep armies immobilized, Grant wired Thomas that he was still worried about the threat of a Rebel army moving toward the Ohio River. At that moment, Hood’s soldiers were shivering in their trenches and fortifications while bitterly cold winds howled around them and Union artillery shells rained down. The Confederates’ own artillery was silent, conserving ammunition for the battle to come. All along the line, vicious skirmishing and sharpshooting were taking place day and night.

Thomas Prepares His Attack

The weather finally took a turn for the better on December 13, and the morning of the 14th brought clear skies and a warm sun. The suffering of the Confederates in their trenches eased, but when the ice and snow began to melt, Hood’s army found itself mired in a sea of mud. Thomas was ready to launch his attack. He called his commanders together, told them the attack would begin on the morning of December 15, and meticulously explained the role of each corps. He would sally forth with a combined infantry and cavalry force of 54,000 men while leaving 9,000 to man the city’s defenses.

It would be none too soon. Grant was en route to Washington and planned to travel to Nashville by rail to personally assume command. Thomas chose a tactic favored by the other Union commanders. Steedman would move out at first light against the Rebel right and conduct a strong demonstration, tying down as many enemy units as possible in an attempt to mislead Hood about where the major attack would be made. On the far right, Brig. Gen. James Wilson’s entire body of cavalry, together with Smith’s infantry corps, would make a grand left wheel, assaulting and overlapping the enemy left. In the center, Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Wood’s corps would serve as the pivot for the wheel and threaten the enemy salient on Montgomery Hill, a mere quarter mile south of Thomas’s command post on Lawrence Hill. Schofield’s corps would be held in reserve between Smith and Wood, to be used according to developments on the battlefield. Apprised of the war council at the last second, Grant muttered to his staff, “Well, I guess we won’t go to Nashville,” and settled in to await word from the front.

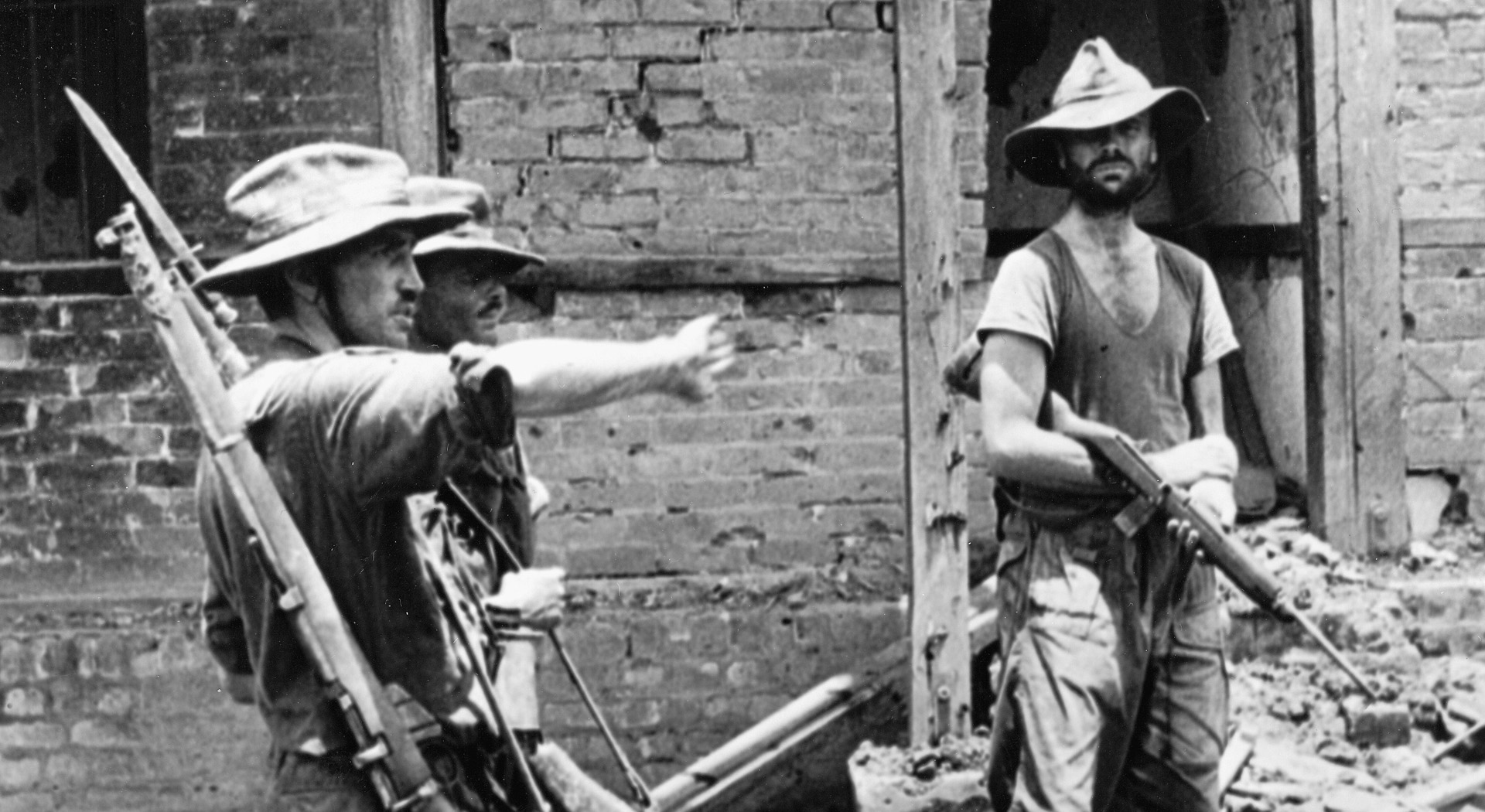

The morning of December 15 broke warm and sunny, but a thick fog obscured the field until late morning. The fog and the uneven nature of the ground partially hid the first movements of Steedman’s units when they sallied forth on the left, two hours late owing to the fog. The Union vanguard consisted of the 1st Colored Brigade under Colonel Thomas Morgan, the 2nd Colored Brigade led by Colonel Charles Thompson, and a motley brigade of white convalescents, conscripts, and bounty jumpers under the command of Colonel Charles Grosvenor.

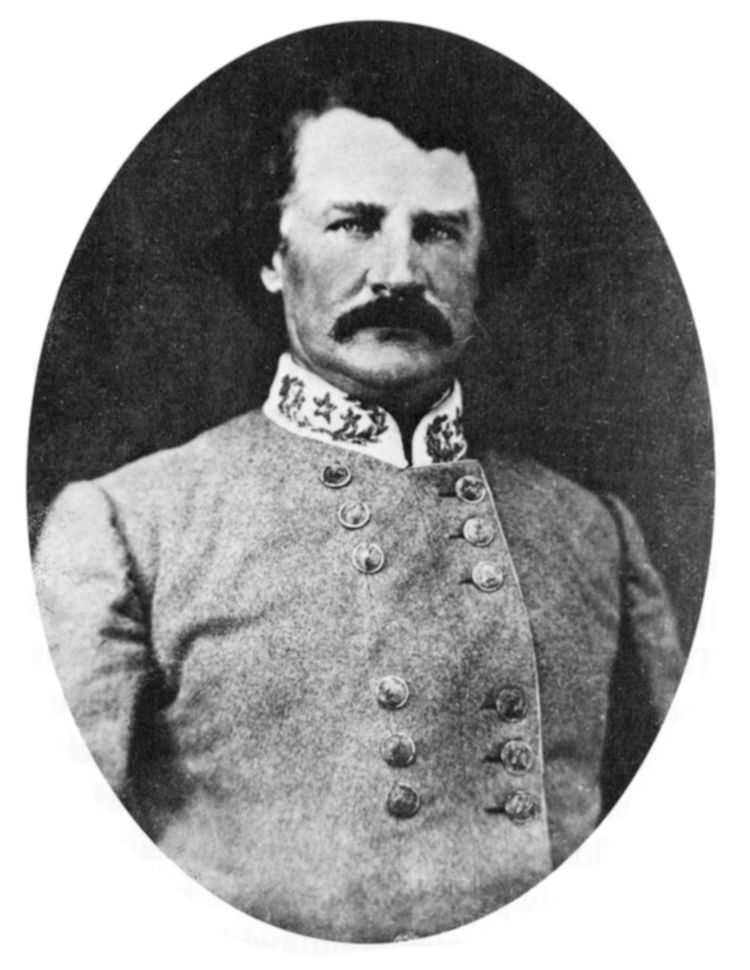

Hood’s right rested on a deep railroad cut between the Nolensville and Murfreesboro Turnpikes. Raines Hill, astride the former, was an imposing terrain feature held by veterans of Maj. Gen. Benjamin Cheatham’s corps. A concealed lunette just to the east, across the tracks of the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad, was occupied by 500 survivors of the late Brig. Gen. Hiram Granbury’s Texas Brigade. From Nolensville Pike, Hood’s line ran west across Franklin Pike, past Granny White Pike, to where Redoubt 1, the true salient of Hood’s left, lay just east of Hillsboro Pike. From there the line “refused” at a right angle to Redoubt 2, also on the east side of the pike. The Confederate line stretched diagonally across the pike to Redoubts 3, 4, and 5. A division of Lt. Gen. A.P. Stewart’s corps was set behind a stone wall that ran parallel to Hillsboro Pike, constituting the extreme left flank of the Confederate works.

Morgan’s Troops Forced to Fall Back

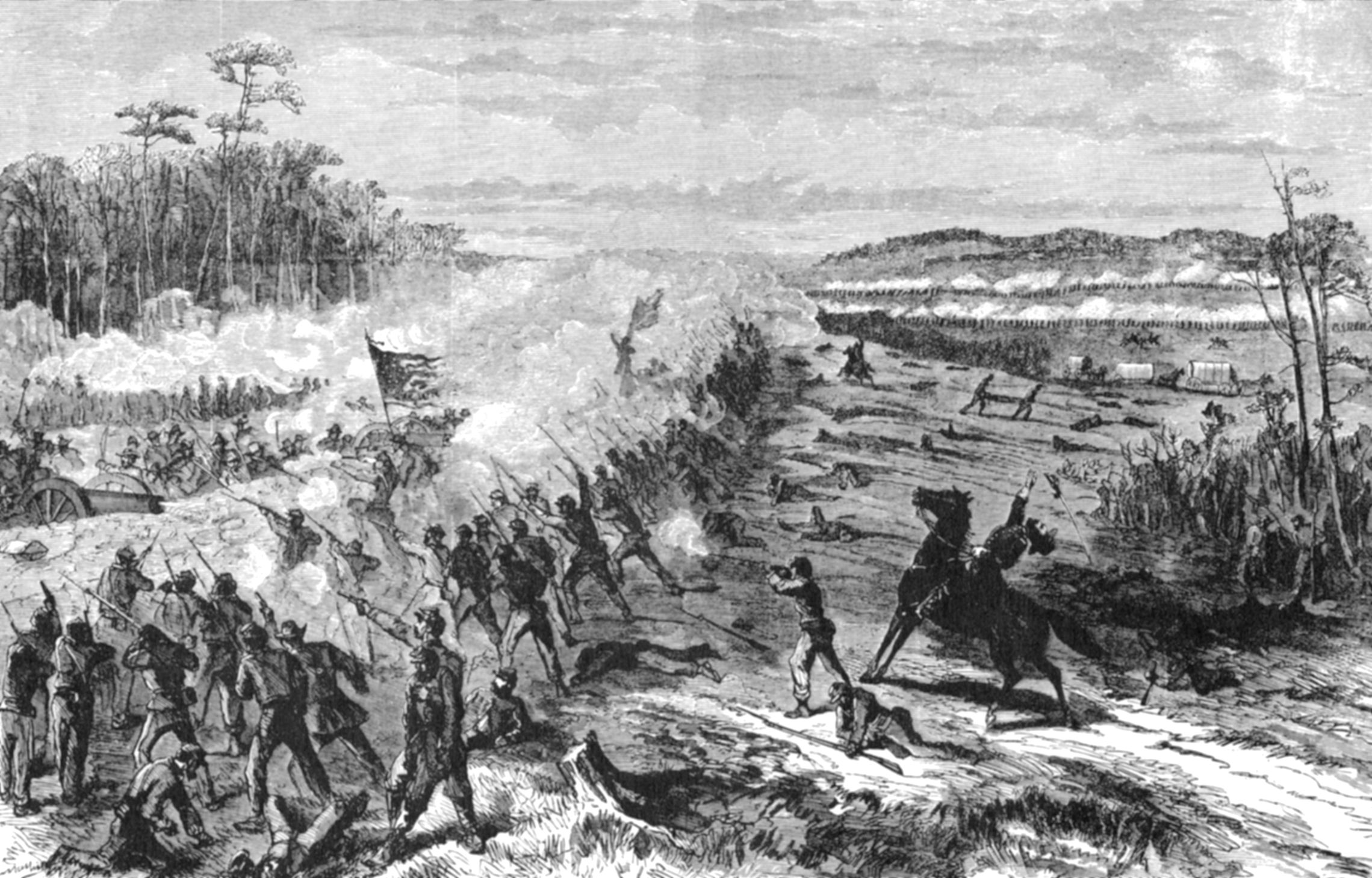

A little after 8 am, Steedman’s three brigades, 7,600 strong and augmented by two batteries of artillery, advanced toward Cheatham’s works, driving back the Confederate skirmish line. The brigades of Grosvenor and Thompson advanced directly on the main works, while Morgan’s three regiments of 3,200 black troops moved out to the left directly toward the hidden lunette. When Grosvenor’s columns came within range, they were shredded by withering artillery and musket fire and fled in disarray out of range, where they were content to remain for the rest of the day.

Next came Thompson’s brigade, which received the same harsh reception and also stalled. The Confederate veterans waiting inside the lunette held their fire while Morgan’s troops continued forward. When the black troops moved onto the cut and within range, the Texans rose and delivered a terrible volley of musket fire into their ranks. Southern artillery then let loose a torrent of shells, and fire coming from the works west of the cut caught Morgan’s men in a deadly crossfire.

Under such a pounding, Morgan’s troops were forced to fall back. They quickly regrouped and reformed for another advance, as did the four regiments of Thompson’s brigade. The black troops came on once more, only to be halted again. This went on for a good two hours. At 11 am further advances were halted, but the attackers remained within musket range of the Confederate works and stayed in contact with Cheatham’s right flank for the remainder of the day’s fighting. The black units had done everything asked of them, suffering severe losses in the process.

On the Union right, the corps of Wilson and Smith were delayed for some time while several divisions of infantry were being aligned properly. At 10 am the commanders began moving their two corps, seven full divisions in all, out of their works to initiate the grand movement of the day. Wilson’s troopers, 9,000 mounted and 3,000 dismounted, moved out in a westerly direction, parallel to Charlotte Pike, then they wheeled to the left, crossed the pike, and moved southward toward Harding Pike. The first Rebel forces Wilson’s men encountered were the skirmishers of the understrength, 700-man brigade of Brig. Gen. Matthew Ector (who was not present, having lost a leg at Atlanta). Hood had placed the brigade behind Richland Creek, between Charlotte and Harding Pikes, to provide some help to General James R. Chalmers’s badly outnumbered cavalry brigades. Wilson’s troopers advanced rapidly on Ector’s small force, capturing a number of prisoners and wagons, but the bulk of the defenders fired off a couple of volleys and then headed back toward the main Confederate works on Hillsboro Pike as ordered. Chalmers’s outnumbered force put up a spirited defense on Charlotte Pike, holding back an entire division of Wilson’s troopers, but it was simply too small to be much of a factor in the rest of the day’s fighting.

Can the Fort Be Held?

Smith’s corps moved out simultaneously with Wilson’s men. Bearing left, the corps moved across Harding Pike and advanced toward the Rebel works strung out along both sides of Hillsboro Pike. When reports began streaming in to Stewart about large movements on his left, he was well aware of what was happening—the enemy was trying to turn his flank. He immediately requested reinforcements. Hood ordered Maj. Gen. Stephen D. Lee, whose corps had scarcely been touched, to send one division to Stewart and ordered Cheatham to dispatch Maj. Gen. William Bate’s division to the left as well.

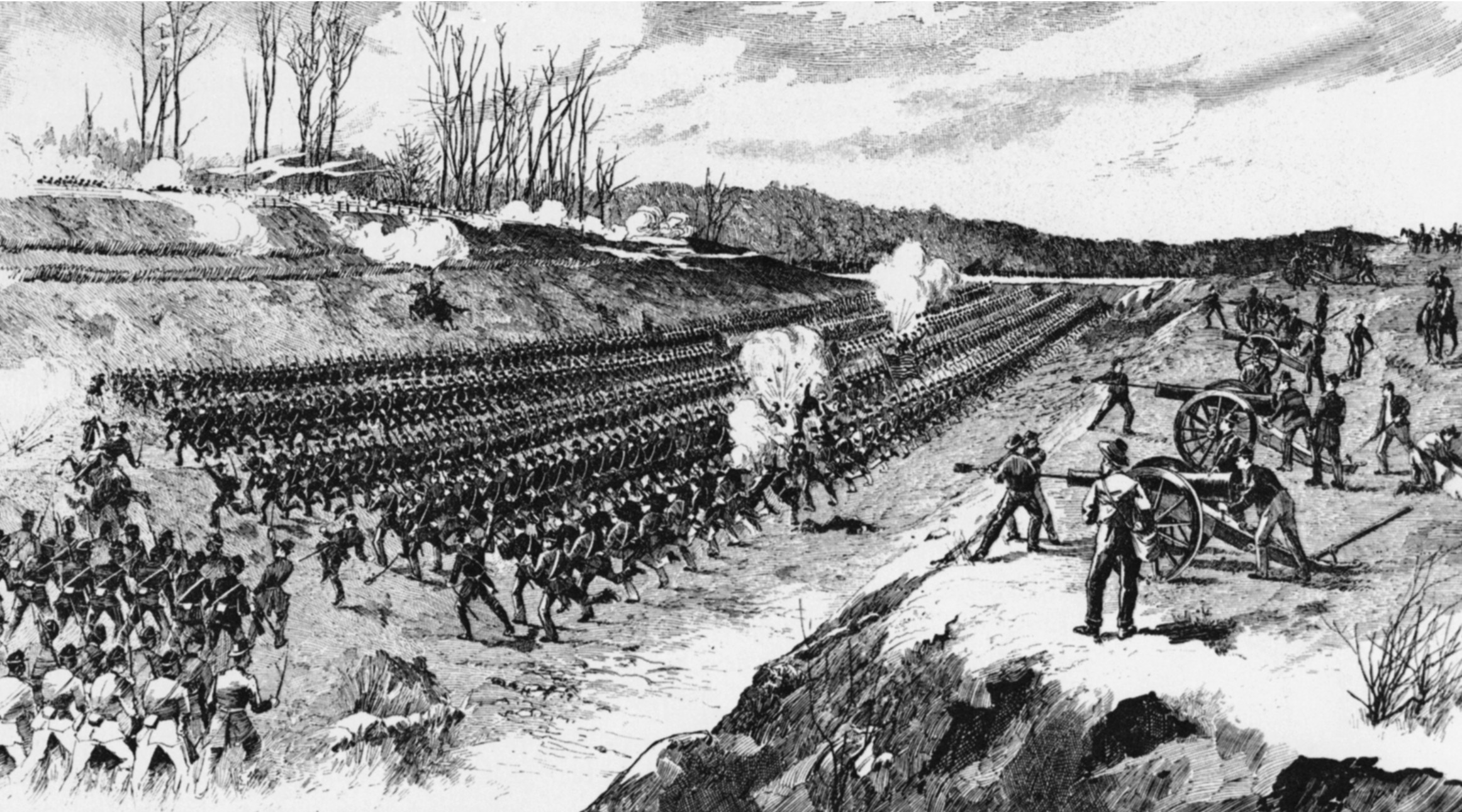

As the two Union corps, more than 20,000 strong, moved forward across Harding Pike and approached the mile-long extension of the Confederate left along Hillsboro Pike, three of Hood’s Redoubts—3,4, and 5—nestled along the west side of the pike, came into view shortly before noon. Each of the forts boasted a four-gun battery of 12-pounder smoothbore Napoleons, fairly accurate up to about half a mile. Inside the works, 50 cannoneers and 100 dug-in riflemen had been told to hold their positions at all hazards.

Between noon and 1 pm, while in the Union center Wood was about to get the order to attack Montgomery Hill with his corps, Wilson and Smith opened fire with their rifled pieces on Redoubts 3, 4, and 5; after a good hour’s bombardment, the blue columns advanced again. The Confederates answered with volleys of double-shotted canister, halting the blue waves at least temporarily in front of Redoubts 3 and 4. Redoubt 5 was left exposed on Stewart’s far left. Hit from front and flank, Redoubt 5 fell fairly rapidly, with the loss of its four guns, overwhelmed by a brigade of Wilson’s dismounted troopers and a brigade of Smith’s infantry.

The captured fort’s guns were quickly turned on Redoubt 4, next in line, which was already being heavily shelled by the 16 guns placed in its front by Smith and Wilson. Inside Redoubt 4, Captain William Lumsden, a Virginia Military Institute graduate and former commandant of cadets at the University of Alabama, blazed away at the enemy with his gunners and 100 riflemen of the 29th Alabama. At 11 am, Lumsden called to the officers and asked them to stay and help him hold the small fort. They replied, “It can’t be done. There’s a whole army to your front.” It took almost three hours after the commencement of the initial artillery barrage before the attackers could finally overwhelm Lumsden and his garrison. When the end was near, Lumsden cried out, “Take care of yourselves, boys,” and scrambled back with the survivors to the main Confederate works west of Hillsboro Pike. It was by now almost 3 pm; with the reduction of Redoubts 4 and 5 complete, the Union batteries displaced forward to focus their attention on the stone wall running along the eastern side of the pike.

Wood’s Soldiers Anxious to Play Their Part

Hoping that Wilson could extend his attack even further against Hood’s flank and rear and possibly even gain a foothold on the vital Granny White Pike, Thomas ordered Schofield to move up with his two divisions, held in reserve near the Union salient on Lawrence Hill, into the pocket between Smith’s corps and Wilson’s cavalry. This movement went off without a hitch, and soon Schofield’s corps of about 12,000 men was in position to join the general attack threatening to bury Hood’s left along Hillsboro Pike.

By early afternoon it was almost time for Wood’s anxious soldiers to play their part in the massive left wheel. All morning, the men of Wood’s IV Corps, the largest in Thomas’s force at 16,645 strong, had waited near Lawrence Hill while Steedman’s corps moved out to their left and Smith and Wilson’s on their right. Almost all the men were veterans of Franklin, where Wood had assumed command after Maj. Gen. David S. Stanley was wounded. Still a brigadier, Wood was trying to erase what he felt was an unfair stain on his record dating back to the Battle of Chickamauga, 15 months earlier, when he had obeyed a faulty order to pull his men out of line immediately before the massive Confederate breakthrough. Now Wood’s corps advanced on the Rebel salient on Montgomery Hill, which was nothing more than a line of nearly empty works manned by a skeleton force of skirmishers.

From his post on the near side of the valley, Wood marveled at the imposing sight of his attackers. At about 1 pm, the pickets of Maj. Gen. William Loring’s division looked out from their trenches along the crest of the hill and spotted Wood’s blue lines coming up the slope toward them. The handful of butternut-clad infantrymen fired off a few volleys and then prudently headed for the rear. In a matter of minutes, Wood’s legions came up and over the parapets and into the barren line of works, capturing a small number of prisoners. The assault, although successful, had only driven out the advanced forces of Stewart’s corps; the main Rebel salient at Redoubt 1 was still intact.

Furious Shelling from Wood’s Men

While Wood was attacking, the fighting farther west continued unabated. Under an umbrella of artillery fire, Brig. Gen. John McArthur’s division advanced on the stone wall along Hillsboro Pike, routing the defenders with surprising ease. The two brigades there were reinforcements whom Hood had withdrawn at about noon from his center, and when they arrived they had been placed on Maj. Gen. Edward Walthall’s left opposite Redoubt 4. Walthall’s three brigades had been taking a terrible pounding for several hours from the Union artillery and had been holding firm, but when the units on their left collapsed, they began to give ground as well. By now, Stewart could see disaster looming. Two more brigades from Lee had come up, but they were little help holding back the blue wave that had breached Hillsboro Pike. A brigade of McArthur’s division advanced on Redoubt 3, and, although the defenders there greeted the attackers with a fierce blast of grapeshot and canister, the Federals pushed forward and carried the fort and its four guns. When they began taking fire from the defenders on Redoubt 2, McArthur’s men stormed that fort and took it as well.

After the success of his initial attack upon Montgomery Hill, Wood realized that Redoubt 1, on a high hill to his front, was the crucial Rebel position, and he brought up two batteries of six guns each to deliver a converging fire on the salient. The vital angle in Stewart’s line, with Walthall’s division to its left and Loring’s to its right, was being held by a brigade under the command of Brig. Gen. Claudius Sears. After a half hour of furious shelling, Wood ordered Brig. Gen. Washington Elliot to attack the salient. At 4:30 pm, angry because Elliot had delayed his attack, Wood ordered Brig. Gen. Nathan Kimball to do the honors instead. With darkness approaching, Kimball promptly sent his division forward, and within minutes it breached the crest of the hill from the northeast. The men of Elliot’s division were close behind, as well as a brigade of McArthur’s coming in from the west. Four guns and a number of prisoners were taken.

Hood Counts Up His Losses

Stewart, his left overlapped by Wilson and his line along Hillsboro Pike crumbling, saw the inevitable coming and ordered Walthall and Loring to fall back. He was establishing a new line near two hills that shielded Granny White Pike. While Stewart’s corps was withdrawing in fairly good order, Colonel David Coleman’s troops, cut off during the fighting along Hillsboro Pike, fell back to Shy’s Hill, where they were met by Hood, who told them to hold at all costs. Bate’s division, which had arrived after marching over from the right flank, was ordered into a defensive position on a hill north of Coleman’s brigade. A division of Schofield’s corps, hungry for action, came up and drove Bate’s division off the hill, but when night fell the fighting ended and both armies bivouacked in place.

After Hood ordered Lee and Cheatham to withdraw their corps, Stewart pulled his various units together into a fairly solid line that connected at its northern end with Lee’s unshaken left flank. Stewart’s task was made easier by confusion in the Union lines caused by wild celebrations of victory. The intermingled units of Smith, Wood, Schofield, and Wilson, whose dismounted troopers had skirted Stewart’s left and gained a foothold near Granny White Pike, halted for the night in the open fields.

Hood’s left had taken a frightful pounding. Lost were 16 artillery pieces and some 2,200 soldiers, more than half of whom were captured when the Confederate left caved in. Thomas, believing that Hood might retreat, made plans for a pursuit, but several officers who knew Hood well, including Schofield, assured their commander that the battle was far from over. That night Hood established a new line of works along a span of hills two miles south of his original position. His men feverishly threw up breastworks along the front and heavily fortified two hills that would anchor the new line, Shy’s Hill on the left and Overton Hill on the right.

Hood instructed Cheatham, whose corps moved from the right flank to the left, to have Bate’s division join Coleman’s depleted brigade on Shy’s Hill. When the alignments were made, Hood had some 5,000 infantry on his left, 1,500 of them on Shy’s Hill. Anticipating a repeat of the first day’s tactics by Thomas, Hood told his chief engineer, Colonel S.W. Prestman, to select a line on which the reformed defenses could adequately protect the army’s left flank. The line Prestman chose was not at the military crest of Shy’s Hill, but farther down the reverse slope. If the Union attackers detected this flaw, they would be able to mass large numbers of troops in front of the hill, shielded from direct rifle fire, for a massive assault.

Wood Advances His Troops At First Light

To complete his new line, Hood put Stewart’s exhausted corps in the center and Lee’s corps on the right. Two fresh divisions, those of Maj. Gens. Henry Clayton and Carter Stevenson, which had seen only light action on the previous day and hadn’t been committed at Franklin, dug in astride the Franklin Pike and on the crest of Overton Hill. The line on Lee’s right bent back sharply to the southeast of the pike. Thomas had decided to combine Wood’s corps with Steedman’s provisional division to batter Hood’s right, in hopes of turning Hood’s flank and gaining a foothold on the crucial Franklin Pike. The assault by Steedman’s brigades would be an all-out attack, unlike the demonstrations of the first day.

At first light on the 16th, Wood advanced his corps toward Franklin Pike, pushing back the lines of Rebel skirmishers. Wood put one division on the pike and one on its left. With his third in reserve, he began moving south toward the new Rebel line. About a half mile from Lee’s new works, Wood’s corps encountered a heavy enemy skirmish line in front of Overton Hill. He brought his reserve division into line, and the entire IV Corps advanced, three divisions abreast, driving Lee’s skirmishers back into their lines under heavy musket and artillery fire. Wood then halted the column to await the major assault set for later that afternoon.

At 6 am, Steedman had moved forward to find the Rebel works to his front abandoned. He continued along Nolensville Pike, feeling for the new Confederate front, and took up position between Nolensville Pike and the left of Wood’s corps. There he remained until early afternoon, when he was ordered by Thomas to connect with Wood’s left and prepare for an assault. Meanwhile, on the Union right, Wilson went into action at 9:30 am, intending to move his dismounted troopers forward, connect with Schofield’s right flank, and hit the Rebels on the hills to his front. But the wet, muddy terrain and unexpectedly fierce resistance halted Wilson almost immediately, and when Thomas rode over to confer, Wilson suggested that his entire body of cavalry move over to Hood’s right and have a go at it there. Thomas refused.

Time to Take Overton Hill

Other than the skirmishing on the Confederate right, no serious fighting took place until late in the afternoon. The morning hours were marked by an extremely accurate and continuous Union artillery barrage along the length of Hood’s new line, with Shy Hill and Overton Hill taking especially heavy punishment. The Confederate smoothbores, fewer in number, were no match for the more than 100 Union rifled pieces that tore into the breastworks the gray-clad infantry had worked so hard to throw up the night before. Bate’s division on Shy’s Hill suffered under a particularly galling crossfire from three directions. A short distance to their front, one of Maj. Gen. Darius Couch’s batteries was firing at them from almost point-blank range, and during the course of the day delivered a staggering 560 shells onto their works.

During the morning and early afternoon hours, the Union troops on Lee’s front launched a number of probing attacks. When it seemed that the fighting on his right might escalate, endangering his hold on Franklin Pike, Hood withdrew three brigades of Smith’s division from their positions left of Shy’s Hill and sent them to support Lee on the right. This decision would come back to haunt Hood—by the time these troops arrived, the attack on Overton Hill had been repulsed and there wasn’t enough time for them to get back into position on Bate’s left.

Lee’s front had been taking heavy and accurate artillery fire, but the bulk of Hood’s artillery at Lee’s rear answered back furiously. At about 3 pm, with light rain falling, Wood felt that the time was right to overrun Overton Hill. He sent his columns forward. The brigade of Colonel Sidney Post took the lead, with that of Colonel Abel Streight in support. Steedman’s two USCT brigades, seven regiments in all, moved up on Post’s left as the assault began.

Wood’s attackers reached the base of Overton Hill and moved steadily up the slope through a hail of Confederate musket, grapeshot, and canister fire. At the outer edge of the works, Post was wounded and Lee’s infantrymen rose in their trenches and delivered a terrible volley of musket fire that brought the advance to a sudden halt. Wood recalled later, “After the repulse our soldiers, white and colored, lay indiscriminately near the enemy’s works at the outer edge of the abatis.” Steedman’s 13th Regiment, made up primarily of contrabands, suffered heavy losses in its baptism of fire—55 killed and 165 wounded. Its loss of 40 percent of its strength constituted the greatest regimental loss of the two-day fight on either side.

“For God’s Sake, Drive the Yankee Cavalry From Our Left and Rear or All Is Lost”

Meanwhile, on the Union right, Wilson’s gamble paid off. With two mounted and two dismounted divisions, he had finally forced Chalmers to give ground and had strengthened his foothold on Granny White Pike. Wilson’s troopers captured a courier who was taking a message from Hood to Cheatham that read, “For God’s sake, drive the Yankee cavalry from our left and rear or all is lost.” Wilson now felt that victory was at hand. Once he had managed to gain Cheatham’s rear, he would join Schofield in a general attack.

For two solid hours, Wilson sent couriers to Schofield, urging him to begin his attack, and finally Wilson proceeded to Schofield’s headquarters in person. By this time, the attacks on Overton Hill were subsiding, and Thomas was en route to Schofield’s headquarters as well. Schofield was being strangely hesitant. Having already received one full division of reinforcements, he was now requesting another before he would begin his attack, fearing heavy losses if he attacked Hood’s breastworks. Thomas bluntly told him, “The battle must be fought, even if men are killed.”

While Thomas was imploring Schofield to begin his advance, the group of officers suddenly witnessed a brigade of McArthur’s division, under Colonel William McMillen, advancing toward Shy’s Hill without waiting for permission. Thomas turned to Schofield and said, “General Smith is attacking without waiting for you. Please advance your entire line.” With this direct order, Schofield finally advanced.

A Quick Collapse

Cheatham’s soldiers, battered by Union artillery, now faced corps-sized attacks to their front and flank. They could also see Wilson’s dismounted cavalrymen rushing over the hills to their rear. With his left under so much pressure, Cheatham brought up reinforcements and bent his far left flank into the shape of a fishhook, until he had one line of infantrymen firing to the south and another line firing to the north. Only 100 yards separated the two lines. Hood pulled Coleman’s brigade off Shy’s Hill to set up a front on the extreme left, on the east side of Granny White Pike, to hold off Wilson when he was reinforced by another brigade. Bate had to further thin his lines on the hill to cover the position vacated by Coleman’s troops.

The brigade on Bate’s extreme left, that of Brig. Gen. Daniel Govan, was driven back down the hill and into a field behind Bate’s division. Govan’s brigade was the only one left on Bate’s flank, the other three brigades having been sent to support Lee, and had been tasked with covering a front originally assigned to an entire division. Minutes later a fatal breach occurred. Union infantry had massed in strength, almost undetected, on the steep slope to the front of Shy’s Hill, and as they came up and over the hill they encountered the 20th Tennessee under Colonel William Shy. As other units began fading away, Shy and his men stood firm, and the fighting escalated into savage hand-to-hand combat. Shy’s men continued firing until they ran out of ammunition and were surrounded. Shy was shot in the head and killed, and almost half his unit was killed or wounded. The 37th Georgia, on Bate’s left, also fought savagely until it was overrun and virtually wiped out.

With Smith to their front, Schofield to their left, and Wilson coming up from the rear, Bate’s men were buried under the weight of overwhelming numbers; all three brigade commanders were captured. “The breach once made,” Bate recalled later, “the lines lifted from either side as far as I could see almost instantly and fled in confusion.” Panic began to spread among Cheatham’s units on the left and Stewart’s in the center. Soon the bulk of Bate’s three brigades turned and headed for the rear in full retreat. On the northeastern front, the men of Steedman’s and Wood’s corps, hearing the shouts of victory coming from the Union right, renewed their assaults without waiting for orders, capturing 14 guns and hundreds of prisoners.

The Confederate artillery commander, Maj. Gen. Edward Johnson, was captured along with almost all of his division and the remaining guns. The collapse came so quickly that the batteries’ teams of horses couldn’t be brought up quickly enough to draw away the guns. Watching from horseback, Hood was astonished. Only an hour earlier his lines had been holding, his men in the center and right waving their battle flags in defiance. He had even decided on a plan to achieve victory the next morning—he would withdraw his entire army during the night and attack the Union left at dawn. Now, with full darkness approaching, Cheatham and Stewart had caved in, their men fleeing en masse for Franklin Pike, the only remaining avenue of retreat. Hood, Cheatham, and other officers tried to rally the panic-stricken troops, but it was useless. Everywhere the woods were full of fleeing soldiers, many of whom dropped their weapons and packs to lighten their loads as they ran.

Further Hardships After the Fighting for Both Sides

When the blue legions approached Lee’s corps along the pike and on Overton Hill, one division wavered and broke, and a second faltered. Lee heroically rallied a group of retreating soldiers for a stand behind the center of his line, and this small force checked the blue columns long enough to allow Clayton to withdraw his division and form it in the woods astride Franklin Pike, half a mile away. Both armies were now in motion, heading south. The drizzle turned into driving rain, mixing with the snow on the ground. Franklin Pike quickly became clogged with thousands of shaken soldiers, abandoned wagons, and riderless horses. Hood later wrote, “I beheld for the first and only time a Confederate army abandon the field in confusion.”

With the battle lost, Hood’s task was to save as much of his army as he could. He sent Chalmers with his two depleted brigades to set up a barrier near Granny White Pike. Soon Wilson’s four divisions arrived, and vicious, hand-to-hand fighting ensued in the rain and darkness, lasting long enough to enable Hood to get the bulk of his army safely onto Franklin Pike and headed south. Thomas arrived on the scene, miles in advance of the infantry. “Dang it to hell, Wilson!” cried the normally unflappable commander. “Didn’t I tell you we could lick ‘em? Didn’t I tell you we could lick ‘em if only they would let us alone?”

After two days of heavy fighting, both armies faced further hardships. In the coldest winter in Tennessee in decades, Hood’s ragged army slogged through the rain, sleet, and snow, followed closely by Wood’s infantry and Wilson’s cavalry in a race for the Tennessee River. In his retreat Hood was aided by three factors: inclement weather that turned the roads to mud; lack of forage for the Union pursuers; and the excellent rearguard actions of Lee, Chalmers, and the redoubtable Forrest, who rejoined the army at Columbia. Just as Thomas had been badgered to attack Hood without delay in the first days of December, now he was urged by his superiors hundreds of miles away to mount a vigorous pursuit to complete the destruction of the fleeing enemy. Grant, as usual, had nothing good to say—it wasn’t long before he was telling his subordinates that Thomas was “too slow to attack, not vigorous enough in pursuit.”

When Hood’s dispirited army finally crossed the Tennessee River into Alabama on the night of December 25-26, Thomas called a halt to his pursuit. The Confederate invasion of Tennessee was over, and the gallant Army of Tennessee would never again take the field as an effective fighting force. Despite what Grant and Halleck said—and would continue to say—about his alleged “case of the slows,” Thomas had won one of the most decisive victories of the entire war.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments