By William F. Floyd Jr.

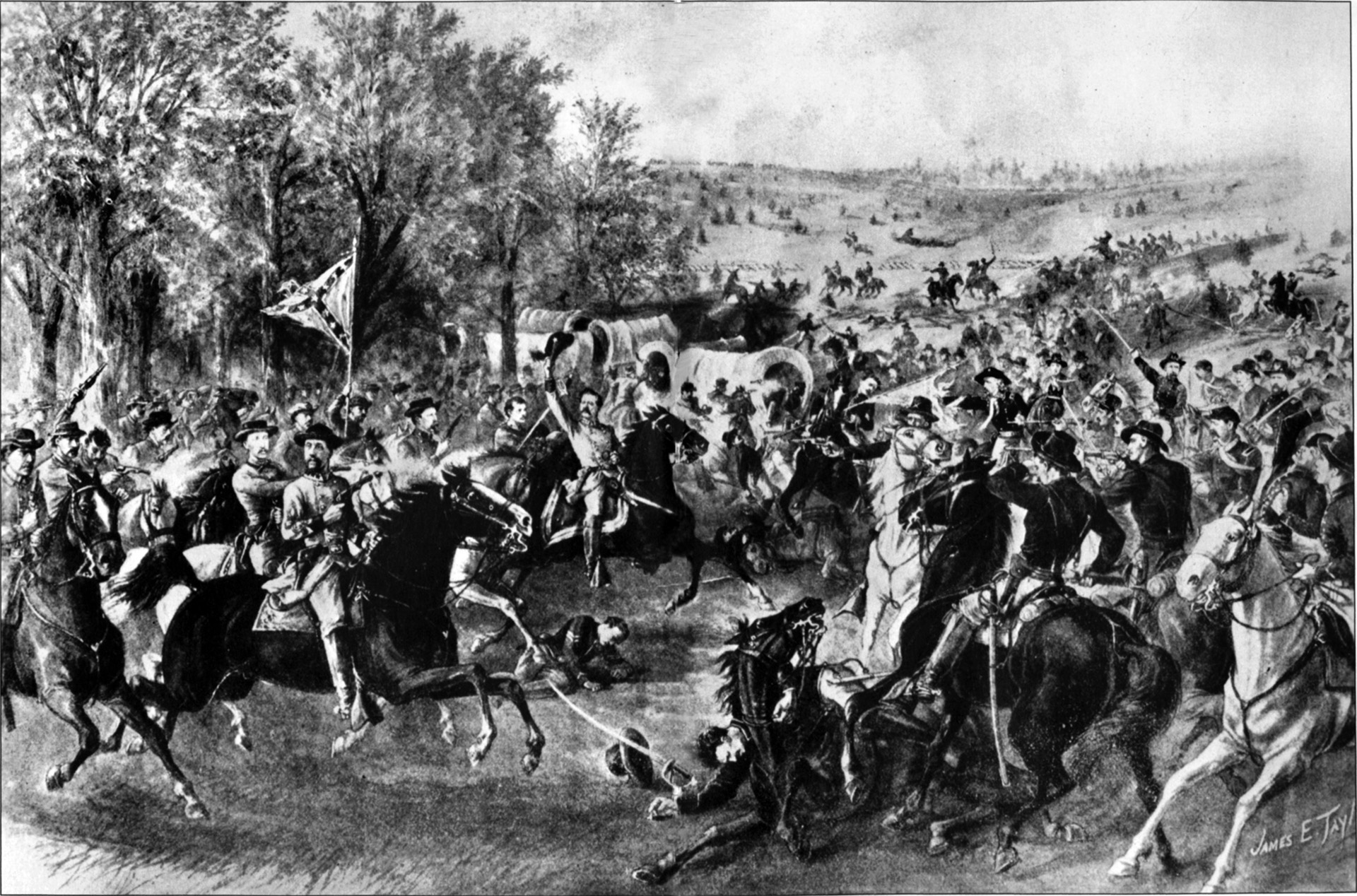

On the morning of July 3, 1863, Confederate Brig. Gen. Wade Hampton III led the troopers of his brigade south along the York Road. Along with other Confederate cavalry forces under the command of Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, their objective was to get behind the Union Army of the Potomac. The gray horsemen went into action against the Union cavalry at 3:00 p.m.

In the confused hand-to-hand fighting on horseback, Hampton received two saber cuts to the front of his head, one of which cut through to his skull. He also was wounded in the body by a piece of shrapnel. Always in the thick of the fighting, Hampton’s performance at Gettysburg was typical of his aggressive conduct as a Confederate cavalry commander.

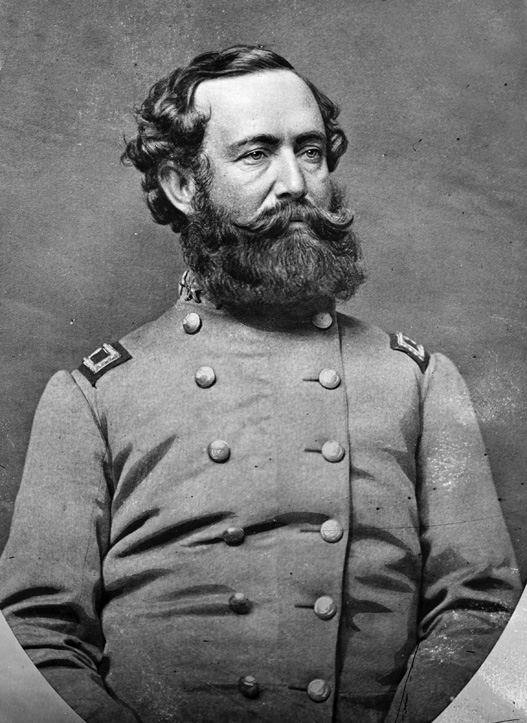

A native of Charleston, South Carolina, Hampton was born on March 28, 1818, into one of the wealthiest families in the South. His father, Colonel Wade Hampton, distinguished himself during the War of 1812, serving first as a lieutenant in the dragoons and later as an aide to Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans.

Young Wade received an excellent education, graduating from South Carolina College in 1836. Although he trained for the law, he never practiced it. Upon his father’s death in 1858, Hampton inherited a substantial fortune owning to his family’s vast landholdings. He served in both houses of the Palmetto State legislature from 1852 to 1861.

With war looming in early 1861, Hampton organized and financed with his own money a military unit known as the Hampton Legion. As a combined-arms unit, the Hampton Legion consisted of six companies of infantry, four of cavalry, and an artillery battery. As a member of one of the state’s most influential families, he had no trouble securing the rank of colonel in order to command the legion.

The Hampton Legion first saw action at First Manassas. As the Union forces drove the Confederates from Matthews Hill, Hampton advanced his legion to the Warrenton Pike to help stabilize the Confederate line. In so doing, he bought time for Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Jackson’s brigade to deploy south of the road on Henry Hill. The legion, which fell back to a position by the Robinson House, repulsed the attack of Colonel Erasmus D. Keyes’ brigade, which sought to turn the right flank of the Confederate forces facing the Union flank attack from the direction of Sudley Springs. In the hard fighting that day, Hampton was grazed in the head by a bullet and had his horse shot from under him.

The Confederate government gave Hampton command of a brigade in Brig. Gen. William H.C. Whiting’s division of Maj. Gen. Gustavus Smith’s Reserve in January 1862. His brigade was composed of the Hampton Legion, 14th and 19th Georgia, and 16th North Carolina. For his aggressive leadership and superb handling of his troops in a clash at Eltham’s Landing on the Virginia Peninsula on May 7, Whiting cited Hampton for his “conspicuous gallantry.” Confederate General Joseph Johnston, the army commander, observed that Hampton was a senior officer of “great merit.” The praise of his superiors secured Hampton’s promotion on May 23 to brigadier general.

The Confederate government gave Hampton command of a brigade in Brig. Gen. William H.C. Whiting’s division of Maj. Gen. Gustavus Smith’s Reserve in January 1862. His brigade was composed of the Hampton Legion, 14th and 19th Georgia, and 16th North Carolina. For his aggressive leadership and superb handling of his troops in a clash at Eltham’s Landing on the Virginia Peninsula on May 7, Whiting cited Hampton for his “conspicuous gallantry.” Confederate General Joseph Johnston, the army commander, observed that Hampton was a senior officer of “great merit.” The praise of his superiors secured Hampton’s promotion on May 23 to brigadier general.

During the Battle of Seven Pines east of the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, on May 31, Hampton’s brigade went into action north of Nine Mile Road against Brig. Gen. John Sedgwick’s division of the Union II Corps. In his attack against the extreme right flank of the Union forces south of the Chickahominy River, Hampton was struck in the foot by an enemy bullet. It was not Hampton’s fault that his brigade was repulsed, given that only nine of the 22 Confederate infantry brigades slated to participate in the attack clashed with Federal forces that day.

Hampton, who refused to leave the field, insisted that a surgeon remove the bullet from his foot while he remained in the saddle with bullets whistling through the air. The newly minted brigadier had “few equals and perhaps no superior,” Smith wrote of Hampton in his battle report.

General Robert E. Lee, the commander of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, established a unified 15,000-strong division of cavalry under Maj. Gen. Stuart’s command on July 28, 1862. Brig. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee, Brig. Gen. Beverly Robertson, and Hampton each received command of a cavalry brigade. Hampton’s cavalry brigade comprised 1st North Carolina, 2nd South Carolina, 10th Virginia, and the Cobb and Jeff Davis legions.

In the outset of the Maryland Campaign that began when Lee’s forces forded the Potomac River on September 4. Stuart led his division across the Potomac at White’s Ford, and then deployed his brigades along the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad on September 5 to screen the movements of Lee’s infantry from Union forces. Hampton initially took up a position at Hyattstown, Maryland.

Hampton’s troopers covered the Confederate rear as the Army of Northern Virginia headed west on September 10. His troopers skirmished with the vanguard of the Army of the Potomac on September 12-13 at Burkittsville and Middleton on the approaches to South Mountain.

During the Battle of Antietam on September 17, Hampton’s troops participated in Stuart’s unsuccessful attempt to turn the Federal right flank in the late afternoon. Stuart tried to gain the Federal rear, but his advance was stopped cold by the 34 guns that Union Brig. Gen. George G. Meade had massed on high ground on Joseph Poffenberger’s farm.

Hampton’s brigade participated in Stuart’s second ride around Maj. Gen. George McClellan’s army in mid-October 1862. Stuart entrusted Hampton with leading the vanguard of the mounted force. When Stuart’s 1,800 troopers reached Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, on the night of October 10, the town’s leaders surrendered to the Confederates.

During the three-day raid, the Confederates rounded up 1,200 horses, plundered the government supply depot in Chambersburg, and destroyed a million dollars’ worth of property. When Lee again reorganized his cavalry that month, Hampton was given the honor of commanding the first brigade in Stuart’s division.

Lincoln sacked McClellan in the aftermath of the Chambersburg raid and appointed Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside to command the Army of the Potomac, an offer he reluctantly accepted on November 7. Stuart entrusted Hampton with independent command that month and instructed him to strike against Burnside’s vulnerable supply line, which stretched from Alexandria, Virginia, to Fredericksburg, Va. With a small number of troopers, Hampton struck small Union wagons trains on November 27 at Hartwood Church, on December 10 at Dumfries and on December 17-18 at Occoquan. His victorious troopers escorted their prizes, consisting of wagons, horses, and provisions, into Confederate lines south of the Rappahannock River. Greatly impressed by these feats, Lee offered the Palmetto State planter command of an infantry brigade, but Hampton declined, preferring to remain with the cavalry.

In the largest cavalry engagement of the war, fought at Brandy Station on June 9, 1863, Hampton performed with distinction. He led a successful counterattack against Union forces on Fleetwood Hill, sweeping them off the high ground. Afterwards, Hampton mourned the loss of his brother, Lt. Col. Frank Hampton, the commander of the 2nd South Carolina Cavalry Regiment, who was mortally wounded in the battle.

Hampton convalesced for four months following the wounds he received at Gettysburg, and he returned to the army in early November 1863. While he was recuperating, he received a promotion to major general in recognition of his gallantry at Gettysburg. That same month, Lee reorganized Stuart’s cavalry into a corps.

The South Carolinian became the de facto commander of the Confederate cavalry corps when Stuart fell mortally wounded in battle at Yellow Tavern on May 11, 1864. Lee was reluctant to make the appointment a permanent one because Hampton was not a professionally trained soldier.

A test of his skill at handling a large body of cavalry came in June, when Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan’s Union cavalry attempted to move west to inflict damage on the Virginia Central Railroad and the James River Canal, two transportation corridors by which the Confederates received supplies from the Shenandoah Valley and the Carolinas. Hampton intercepted Sheridan’s force on June 11, and a fierce mounted battle ensued over the course of two days. Hampton repulsed Sheridan, who had no choice but to withdraw to the Army of the Potomac’s position east of Richmond at Cold Harbor.

Hampton’s victory at Trevilian Station was “a handsome success,” said Lee. In appreciation for Hampton’s brilliant leadership throughout summer 1864, Lee announced on August 11 that Hampton would officially become the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia’s cavalry corps.

Hampton’s troopers participated in one of the most unique raids of the war when they raided the area where Union forces besieging Petersburg kept the cattle to feed their large army. Following a sharp skirmish at Sycamore Church on August 9, 1864, Hampton’s troopers led 2,486 head of cattle back to Southern lines to feed Lee’s famished soldiers.

As the grueling siege of Petersburg dragged on, Hampton’s troopers clashed frequently with Sheridan’s cavalry at various locations outside of the siege lines. Hampton’s 20-year-old second son, Preston, was slain on October 27 in the Battle of Boydton Plank Road, and his eldest son, Wade Hampton IV, was wounded in battle but survived.

In February 1865 Hampton joined Southern forces opposing Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s army, which had turned north into South Carolina after its march of destruction through Georgia. On February 15, Hampton was promoted to lieutenant general.

Waging total war against the South, Sherman’s troops burned everything in their path, including homes, barns, churches, and even entire towns. Although Sherman promised to protect the city of Columbia upon its surrender on February 17, 1865, he failed to stop his troops, who had imbibed great quantities of liquor, from setting fires that destroyed the city. Hampton had withdrawn his cavalry from the city upon its surrender. Hampton was present when General Joseph E. Johnston, the commander of the Confederate Army of Tennesee, surrendered to Sherman on April 26, 1865.

Worn down from his long service to the Southern cause, Hampton returned to Columbia, South Carolina, in summer 1866. With his finances in such poor shape as a result of the war he filed for bankruptcy. A Democrat who vehemently opposed Radical Reconstruction, Hampton was elected governor of South Carolina for two short terms in 1876 and 1878. During his tenure as governor, he appointed a number of African Americans to prominent state offices.

While governor, Hampton suffered a painful injury to his leg that resulted in the lower portion having to be amputated. Because of this, Democrat William Dunlap Simpson completed Hampton’s second term while he convalesced.

Hampton went on to serve two terms in the U.S. Senate from 1879 to 1891. He later served as the commissioner of the Pacific Railway from 1893 to 1897. After struggling with declining health for a number of months, Hampton passed away in Columbia, South Carolina, on April 11, 1902.

Hampton and Stuart were never close and maintained only a cordial relationship. One of the reasons for this was that Hampton resented what he perceived as favoritism in appointing Virginians to leadership positions in Lee’s cavalry. Hampton possessed a combative nature, and during the Gettysburg campaign his intense rivalry with Maj. Gen. Fitzhugh Lee had caused considerable difficulties.

Hampton, along with Nathan Bedford Forrest and Richard Taylor, had the distinction of being one of three Confederate commanders to achieve the rank of lieutenant general without having any formal military training. Although he lacked Stuart’s dashing style as a cavalier, Hampton made up for it with his courage, his ability to carry out difficult raids, and his superb handling of large cavalry commands in the final months of the war.

In this fine article I see you claim the drunken union soldiers burned Columbia to the ground.

I believe many scholars and historian blame the confederate for burning cotton bales so the union would not get the cotton and with a fierce wind, Columbia burned.