By Richard A. Beranty

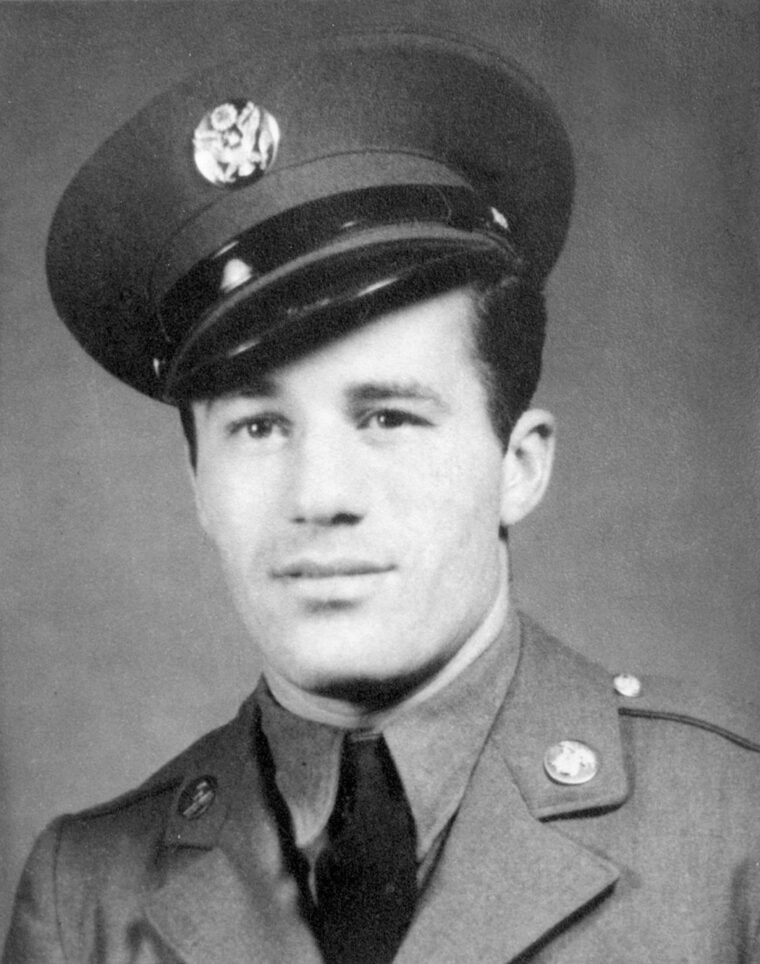

Angelo J. “Red” Mantini was hardly an angel growing up in the small coal-mining towns of western Pennsylvania in the 1930s. By his own admission he was kicked out of school more than once for being a troublemaker, a character trait that did not endear him to his teachers.

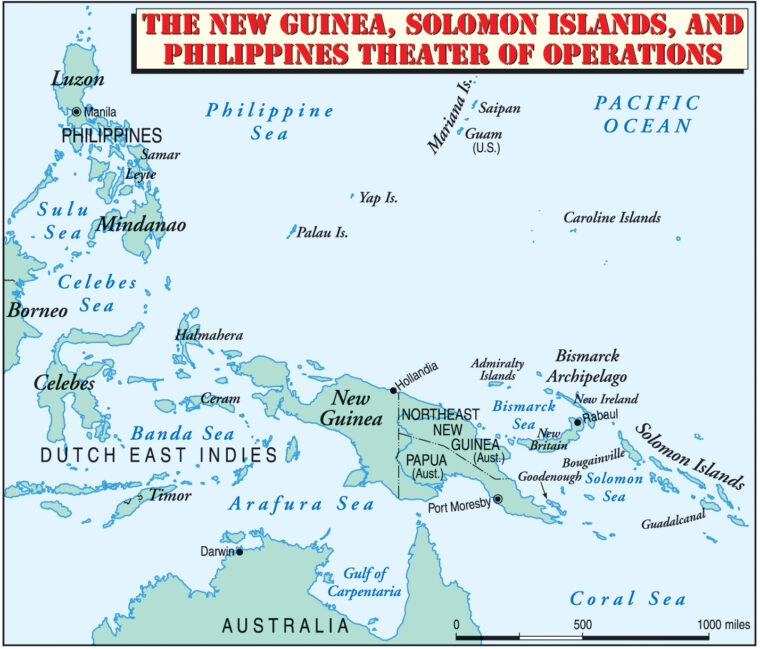

But the penchant he showed for getting into fights, along with the grit and savvy he possessed to win them, would serve him well during World War II on New Guinea and in the Philippines, where he proved to be as quick with the trigger on his Thompson submachine gun as he had been with his fists. Whether you stood on a dark street corner in America or pushed your way through the dense undergrowth of a sniper-infested jungle, Mantini was the kind of fighter you wanted to have on your side.

“I was always pretty quick with my hands,” offers this 85-year-old retired shoemaker from Ford City, Penn., explaining his reputation as a person not to mess with in Hometown USA. “And I had a pretty good reputation in the Army. Nobody would fool with me, not even the company commander. I didn’t take crap off of nobody.”

With an attitude like his it is little wonder that Mantini found himself doing time in the stockade, or busted in rank, several times during the war. Rarely did he take guff from anyone, including his higher-ups, which is why, at various times, he was a sergeant, then a private, then a sergeant, and so on. Somebody once remarked about him, “He was up and down like a yo-yo.” But Mantini proved to be a survivor while many of his enemies were not. By war’s end this former platoon sergeant with the 24th Infantry Division was officially credited with killing more than 40 Japanese soldiers in fighting on five different Pacific islands. His success at eliminating the enemy was due in part to the great American pastime of baseball.

Guts And a Deadly Aim

“When we were advancing in combat, I always figured distance by the length of a ball field,” he explains. “I would think to myself, from here to over there is the distance of a ball field, so I’d try to measure it with my feet. I’d go this way 30 feet, then I’d shoot forward another way 30 feet. This one time I ended up right behind a Jap pillbox. There must have been a couple of guys inside of it loafing, because usually there’s only five or six; here there were eight. I was standing there, and I had a white phosphorous grenade. They don’t have any shrapnel, and I never thought too much of their concussion. So I threw it, and I’m waiting for the Japs to run out so I can shoot them.”

The force of the explosion surprised the 130-pound Mantini by hurling him through the air “like somebody picked me up and threw me.” Once he regained his wits, his accurate aim made sure the Japanese fighters fleeing the pillbox never plagued U.S. forces again.

“If I take out a machine-gun position, and I’m the only guy that’s shooting and eight Japs are found dead, I get credit for it. But if three or four of us are shooting, it’s hard to tell who killed them. In that case I probably killed a hundred Japs in the war.”

If Mantini’s view on killing Japanese soldiers seems a bit callous, it is intentional, he says, because of the fanatical practices they employed in battle. Unlike some of their Regular Army German counterparts, who were sometimes willing to surrender rather than fight on for a hopeless cause, the Japanese in the same situation most likely opted to die, at times by their own hands, rather than quit the battle. GIs facing such a scenario have described it as the worst kind of warfare, occurring in obscure jungle places with names that few Americans today would recognize.

Mantini says that when a Japanese soldier was outnumbered and surrounded, he first sought a fighting solution to his dilemma rather than surrender, regardless of the pitiful odds facing him. And if that failed he usually resorted to suicide, called hara-kiri, and tried to take with him as many Americans as he could. This determination for destruction, along with the tactics they used, is why men like Mantini still harbor an intense animosity for the Japanese even today.

“This one time on Leyte Island, the Japs surrounded one of our patrols and killed everyone in it. When we found their bodies, sticks were shoved into their eye sockets and down their throats. I suppose it was done to scare us, but all it did was make us mad. And when we searched some of the Japs that we killed, sometimes we found fingers in their pockets, American fingers, taken as a souvenir. They were dried up and hardly even looked like fingers, but they were.”

Mantini’s journey into the nightmare called the Pacific War began on October 20, 1941, when the 24-year-old was drafted and sent to Camp Lee in Virginia, where he was stationed when the Japanese launched their attack on Pearl Harbor. “I was on a pass in Richmond when the Japs attacked. Loudspeakers everywhere were broadcasting that everyone had to get back to camp. We were told to hitch a ride with any car going our way.”

Trained for duty in the supply ranks, Mantini arrived in Hawaii eight months later and recalls seeing some of the wrecked hulks of ships, remnants of the mauled U.S. Pacific Fleet, still littering the harbor at Pearl. “I was in the Quartermaster Corps when I got to Hawaii. When we got off the ship we were told, 50 drop off here and go over there, 50 drop off and go over there, 50 drop off and go over there. Finally, somebody walked by me and said, ‘Twenty of you break off and go over there. You’re in the 19th Infantry Regiment, Company A.’ They didn’t even look at our service records. Guys like me, who took quartermaster training, were put in the infantry. And guys that took infantry training were put in the Quartermaster Corps.”

Deadly Campaign To Liberate Philippines

The 19th Infantry Regiment to which Mantini was assigned was one of three regiments to comprise the 24th “Victory” Division, one of the few Army units specially trained during the war as assault spearheads for tropical operations. Activated at Schofield Barracks on Oahu in 1921, its stated mission to protect the Hawaiian Islands from foreign attack was realized in December 1941 when it became the first Army ground force to engage the Japanese in combat during those confusing early hours of the war. This gave the division its “First to Fight” designation.

Their brief taste of battle, however, in which strafing Japanese warplanes injured only a handful of men, would pale in scope to what division troops faced three years later when attempting to liberate the Filipino people from their brutal domination by Japanese forces. Called one of the dirtiest, deadliest, and most grueling actions conducted by U.S. forces in any theater during the war, the 10-month Philippine campaign was fought against an enemy who was determined to win or die trying, one who might appear at any time, at any bend in a jungle trail, and one who refused to lay down his arms even after Japan’s unconditional surrender in 1945.

This was the kind of war that awaited the men of the 24th when they left their safe billets in Hawaii for Australia in September 1943 to train for the upcoming invasion of New Guinea. There Mantini’s toughness was noticed by Army officials, and he soon made staff sergeant.

“It was rough training in Australia,” he says, “cross-country and mountain training. We went on a hundred-mile hike one time. Only three of us made it to the end of the trail; just me and two other guys.”

The first of General Douglas MacArthur’s New Guinea campaigns was a two-pronged attack made by the 24th and 41st Divisions to the east and west of the enemy’s large supply and maintenance facility at Hollandia. The main objective of the invasion was the seizure of three airstrips being constructed several miles inland, which MacArthur hoped U.S. bombers could use.

Forming the largest amphibious operation attempted in the South Pacific up to that time, the Hollandia attack force, consisting of more than 200 vessels, left its assembly area off Goodenough Island and put its men ashore 500 miles to the west during the early daylight hours of April 22, 1944. The 41st landed near Hollandia in Humboldt Bay, and the 24th assaulted the beaches in Tanahmerah Bay, 22 miles to the west.

Not only did poor planning and miscommunication among Japanese commanders leave their troops too widely scattered to offer invading forces much resistance, but support from U.S. carrier planes weakened any defensive effort they could muster, and attacks by American submarines on Japanese troop transports coming from China prevented many reinforcements from ever reaching New Guinea. When Mantini went ashore he saw abandoned teapots boiling over fires and unfinished breakfast bowls of rice still on the beach, all left behind in the enemy’s haste to retreat inland when the assaults began. Securing the Hollandia area took just four days at a cost of 171 men to the two divisions. Japanese losses were estimated at 4,000.

“The Japs were on the run; in other words, we had to go into those mountains and look them up,” Mantini says, referring to the densely forested Cyclops Mountains, situated between Humboldt and Tanahmerah Bays, which at night held a surprise for this shoemaker from Pennsylvania.

“They have boars in New Guinea, these little pigs that run in packs and bite like hell. We set up a perimeter one night, and when you set up a perimeter the whole company shoots at anything that moves outside the line after it gets dark. I don’t know what time it was, but it was dark and we were asleep in our foxholes. We tied a string to our finger[s], and when it was time to take watch you pulled the string back, maybe two or three times, to tell the other guy that you were awake. All of a sudden I heard this damn screaming. It was our own men. These pigs were dropping into their foxholes and biting them. I said to the guy next to me, ‘In the morning you and I might be the only two alive when these pigs get done with us.’”

With the Hollandia area in Allied hands and the two divisions linked, Mantini discovered that the souvenir Americans wanted most was a Japanese saber. Air Corps personnel showed the most interest in obtaining one, some willing to pay quite a bit of money for the trophy. Mantini, though, wasn’t interested in the money. “The Air Corps wanted souvenirs. They never had a chance to get any because they were flying back and forth to Australia all the time. Some of them wanted to give me $500 for one, which was a lot of money at that time. But I’d say, ‘No, you won’t buy them. You get us two fifths of whiskey and we’ll give you a saber.’ One time a corpsman from one of the ships wanted a saber. And they had this 100-proof alcohol on the ship. That’s good drinking, better than regular whiskey. So I told the medic the only way he would get a saber was to get me a gallon of that alcohol. He did, and most of the company got drunk on it. That’s how strong it was.

“Another time on New Guinea,” Mantini continues, “this 18-year-old came into my platoon and he was dying to get a Japanese saber, so I told him that I’d get him one. I found one along the trail one day and gave it to this kid. An officer from Company C, a first lieutenant, had lost this very saber. He saw the saber this kid had, recognized it, and took it back. I didn’t know anything about this, and when I came back from a three-day patrol, the kid told me some officer saw the saber, claimed it was his, and took it. I asked if he knew who the officer was, and the kid didn’t know. So I told him if he ever saw him [the officer] again, to point him out to me.

“Three or four days went by, and the kid saw this officer and said, ‘He’s the one.’ I went over and looked and recognized the saber. It was strapped to his duffel bag, so I took it. He came over and said something to me, and I said something to him. Finally I said, ‘If you ever come over and fool with any of my men again, I’ll bust your head wide open.’ So the officer said he was going to turn me in. I said, ‘Go ahead. There’s a command post up there.’ He went up, and the captain told him, ‘Don’t mess with that guy. He doesn’t give a crap what he does to you because he’d be safer in the stockade than he is out here.’”

The job of rooting out the remnants of the five Japanese divisions that were isolated in New Guinea’s interior regions was given to jungle-hardened Australian troops, and by the end of July the island was considered to be in Allied control. MacArthur was now poised for his dramatic return to the Philippines. His original choice for a landing was Mindanao Island, but this was scrapped when an American pilot reported that Leyte Island was manned by far fewer enemy troops than had previously been thought.

While winning back the Philippines was partly an ego issue for MacArthur, the Japanese faced a critical blow to their war-making capabilities if the islands were lost. Not only would a successful American offensive isolate more than 200,000 of Japan’s most veteran fighting troops, but it would also open to attack its shipping lanes from Malaya and the Dutch East Indies, which the Japanese relied on for fuel and rubber. General Tomoyuki Yamashita, the so-called “Tiger of Malaya,” made a promise to his superiors in Tokyo that the Imperial 14th Army would hold Leyte at any cost.

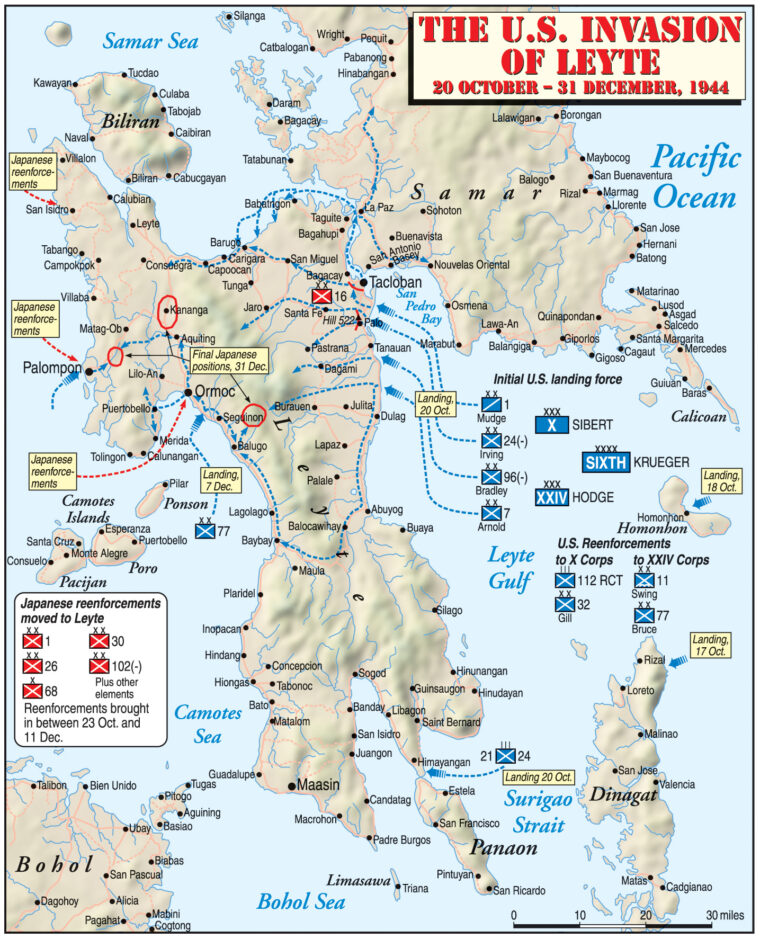

The initial U.S. offensive in the Philippines began on Friday, October 13, 1944, when half the invasion force (the other half originated in Hawaii) boarded transport ships in Humboldt Bay and headed for Leyte. The trip was a lonely and mostly seasick time for the GIs, but it provided them an opportunity to ponder their fate, read, or write letters home. For Mantini, it gave him a chance to play cards and throw dice with other soldiers.

Busted In Rank Yet Again

“They had a rule that, as a sergeant, the first three grades—master, tech, and staff—were only allowed to gamble with those three grades. We weren’t allowed to gamble with the lower grades, privates, Pfcs, and corporals. But all the other sergeants sent their money home before we left. They were all broke. So I was gambling with the lower grades when this major came up to me. They called me Mandy in the army, short for Mantini, and he said, ‘Mandy, you know what the rules are.’ I told him to do what he was supposed to do because I wasn’t about to quit. I was winning. When I got off the boat and on the beach at Leyte, I was a private. Everybody else that came into the company was a regular Pfc, automatic. When we landed on Leyte I think I was the lowest ranked guy there was, and one of the oldest.”

The Philippine ground campaign started on October 20, 1944, when four U.S. infantry divisions landed abreast along an 18-mile front on Leyte’s northeastern coast. The 24th Division was assigned the beach area near the town of Palo, where two of its regiments were to land 3,000 yards apart, the 19th on the southern side of the invasion site and the 34th to its north. Their primary objective of the day was Hill 522, a steep, circular-based, volcanic outgrowth that towered over the coastal terrain about a mile inland. It was one of several hills that guarded the entrance to the Leyte Valley, and the Japanese intended to use it as the key to their defense of the Palo beaches. Months prior to the invasion, much of the male population of Palo had been forced to transform the hill into a labyrinth of machine-gun nests, bunkers, communication trenches, and tunnels.

“We were told to hit the hill, get to the top of it, and wipe out whatever was in front of us,” Mantini says.

That was the situation the Americans faced in the predawn hours of October 20, when the invasion force, accompanied by warships of the U.S. Seventh Fleet, was poised just off Leyte and ready to strike. The naval and air bombardment started soon after daybreak, and anyone standing on the decks of ships could see the silhouettes of other vessels as they began to appear from out of the darkness. Mantini, who was watching this scenario play out, went below, shoved into his pack what personal items he wanted to take, and filled his canteens. He returned topside, gave his weapon a final check, hung six grenades on his uniform, lit a cigarette, and waited to board his assigned landing craft.

“Just before hitting the beach at Leyte is when we started getting a lot of these 18-year-old replacements,” Mantini says. “This one boy, we called him Monaco, came over to me just before we went in and said, ‘Hey, Mandy. Do you have an aspirin?’ I laughed. I said, ‘What the hell do I look like, a walking drugstore?’ Imagine asking me for an aspirin just before an invasion. He said he wanted it because he was so damn scared. I told him, ‘Don’t you think I’m scared, too?’ He said, ‘Nothing scares you, Mandy. You’re not afraid of anything.’ I told him, ‘Like hell I’m not.’”

Mantini says that 18-year-old with the headache never saw another day. In one of those ironies of war, he was killed just after hitting the beach, shot, Mantini points with his index finger, through the center of his forehead.

For everyone connected with the invasion, being “scared as hell,” as Mantini puts it, was a natural state of mind, and for good reason. Never before had they seen such a frightening yet awesome sight. Hundreds of rockets screamed inland while carrier planes and warships bombarded the menacing jungles that loomed in the distance, now burning and smoking from all the attention. After seeing such firepower being unleashed on the enemy’s positions, Mantini wondered to himself how any Japanese could survive the bombardment, and that maybe the invasion would not be too difficult. From what he could tell, the earlier landing craft were making it safely to shore. But Mantini was in a later wave. Still about a thousand yards from Red Beach, some of the boats around him began to take direct hits from Japanese artillery.

“I knew a company commander from a different company than mine. I don’t know why he liked me, but before we left New Guinea I was sitting near a fire, heating coffee, and he came over and said, ‘How would you like to come into my company?’ I said to him, ‘Anywhere is good enough for me.’ He said, ‘I’ll see what I can do.’ Well, I never did get into his company. When we went in at Leyte his boat was next to mine, and a shell hit right in the center of it, killing everyone on board. When things like that happen, it makes me wonder why I survived and other guys didn’t.”

For what seemed to him like an eternity, Mantini’s landing craft slowly crept toward the Leyte shoreline. Finally, the Navy coxswain steering it screamed instructions that no one could hear over the din of battle. As Mantini tightened the strap on his helmet and slipped the safety off his Thompson, the boat came to a stop, the men inside jerked backward, and the ramp clattered down. Pushing their legs through hip-deep water at first, they raced across the narrow beach searching for cover. Mantini flopped belly down and hugged the ground, trying as best he could to hide from the indiscriminate mortar and artillery shells exploding around him. The dead Americans lying nearby were grim testament to the accuracy of Japanese machine guns spewing bullets from concealed positions and the fire of snipers hidden in trees.

“Landing on a beach with the enemy firing at us was the worst part of the war,” he says. “Whenever the door of that landing craft went down, and they started shooting, we took off running like never before. Actually, we weren’t supposed to meet any resistance at all when we landed at Leyte. There wasn’t supposed to be a shot fired. We were told that the Japs were down at this town called Tacloban [the provincial capital of Leyte]. Before we went in on the beach, I guess they all moved from Tacloban to where we landed, because we had a helluva time. MacArthur was supposed to land with us at Red Beach but when he saw that the Japs had come down to our front, it didn’t take him long to leave and go ashore at Tacloban where the picture shows him wading ashore.”

Assault On Hill 522

Confusion ruled those early minutes on Red Beach because a poor landing put the 19th Regiment more to the north than planned and almost directly on top of 34th Regiment troops. Regardless of the error, men, vehicles, and artillery kept pouring ashore. The troops moved forward, either in platoons, squads, or individually, under murderous enemy fire. Some encountered a tank ditch, which kept a large number of vehicles from leaving the beach area, while others met machine-gun emplacements, obstacles that were overcome by the sheer weight of the invasion force.

By early afternoon the 19th Regiment’s 1st Battalion was slugging its way forward in the southern sector of the beachhead toward Hill 522, where it met fire from enemy machine guns blocking the beach road to Palo. With its route blocked, scouting parties were sent to find a rear entrance to Hill 522 and returned with news that a series of paths led to its base. While ships offshore continued their bombardment, and newly arrived division artillery on the beach added its muscle to the fight, the Japanese machine guns were silenced and the GIs moved out in battle formation with Company A in the lead.

As the men advanced through a swamp, scouts met fire from five more enemy bunkers about a hundred yards ahead. Company A was charged with eliminating the obstacles while the rest of the battalion continued around the north side of the hill, skirted the swamp, and attacked from the northeast. The GIs began to climb Hill 522 along its winding paths, at times pulling themselves upward by grabbing vines and roots while laden down with guns, ammunition, and food.

When the assault force neared the hill’s upper reaches, the naval and artillery barrage stopped. It had done its job by driving many of the enemy out of their fortifications and tunnels to the safety of the rear slope. Gaining the hilltop first was Company B, followed closely by men of Company C. They arrived at sunset in twos and threes, quickly established skirmish lines, and dug in for the night, completely exhausted from the day’s battle. It was only a matter of time before the Japanese returned from the far slope to try to regain their abandoned positions.

“Those other companies beat us to the top because we ran into a swamp on the way and it slowed us down,” Mantini says.

Now in possession of the commanding heights of Hill 522, all tiredness seemed to leave the men of 1st Battalion. Fighting that night was constant and close. Grenades were the weapon of choice since they didn’t reveal positions like the blast from a gun muzzle did. With their nerves stretched, Mantini says the GIs had difficulty judging the size of an attack, or discerning if a noise or a shadow was an attack at all.

“It was a long night. Everyone else was doing all the shooting. I never shot at night, but that night I almost did. I was looking at a tree. I kept watching it and watching it and I thought it was moving. Finally, I figured to myself, ‘Jesus Christ, that guy should have been up here by now.’ Then I realized it was a little bush way on down the hill I was watching. If you keep looking at something long enough, you think you see it moving.”

Sleep that night, or even the next, was not an option for the battle-weary men. They could hear the continuous roar of artillery on Red Beach below them, shelling the roads beyond Palo to block Japanese reinforcements from arriving, and clear skies afforded them a view of the ships in San Pedro Bay. Finding himself 10,000 miles from home, Mantini says he wished for two things at the time: sleep and a decent meal. Naturally, neither one materialized.

When daylight broke, the Japanese renewed their attacks with greater zeal. These were men of the Japanese 16th Division, veterans of Manchuria and the conquerors of Bataan, and fighting raged for two more days in a maze of entrenchments. Pillboxes, silenced in the initial attack, came back to life, and tunnels were again full of the enemy. Americans armed with flamethrowers burned out many of them, while another method of extermination was to seal tunnel airshafts and throw phosphorous grenades into the entrances. The burning and choking inhabitants ran outside only to be cut down by American guns. The ability of U.S. spotters on the ground to locate Japanese strongholds on the hillside amazed Mantini.

“I don’t know how Intelligence knew, but they could pinpoint a Jap position exactly. They told us, ‘There’s a gun position here, one over here, and one over here.’ We would go and, sure enough, they were right. I don’t know how the hell they got that information, but they did.”

As other U.S. forces began to chip away at the Japanese fighting at the base of the hill, airdrops provided much-needed ammunition and food to those on top. According to Mantini, it was not unusual for both sides to suddenly halt their fighting in order to gather the dropped rations. Food meant more to them than killing the enemy.

“Whatever dropped on top of the hill, we got,” he explains. “Anything that fell on the sides of the hill, the Japs got. When food was dropped, you could walk all over that damn place because not a shot was fired. The Japs needed the food because they were starving, and we wanted the food, too.”

Hungry, tired, and thirsty, Mantini made a decision that is cited by author Jan Valtin in Children of Yesterday, the battle history of the 24th Infantry Division in the Philippines:

“Weary of being hungry and marooned on Hill 522, Private Angelo Mantini of Kittanning, Pennsylvania, a shoemaker in civilian life, scurried toward Red Beach in quest of food. Halfway down the hill he discovered five snipers who had ambushed a carrying party. Mantini decided that no Nip should prevent him from filling his belly. He killed all five and loaded himself with their weapons. Among the captured weapons was an American automatic rifle. Five minutes earlier, the Division commander, General [F.A.] Irving, had passed the scene of the encounter. The snipers, intent on wiping out the carrying detail, had let the general pass unscathed.”

Mantini Takes Out Snipers

“They probably didn’t know he was a general or they would’ve fixed him,” Mantini says. “Or, they let him go because they were waiting for food. They were hungry and could see that [Irving] didn’t have any. The Japanese didn’t fire until they realized food was involved. Then it was like a war broke out.”

The carrying party mentioned in the account was sent from the hilltop to bring water and food from below, but to do so it had to pass snipers and machine-gun positions. On its way back, this particular detail was pinned down for two hours, and Mantini, seeing its plight, started toward it. From his vantage point above, he spotted a single Japanese sniper. A burst from his Thompson took that enemy soldier out of action. Crawling forward and under cover fire from troops above and behind him, Mantini saw four more of the enemy in another position. Two of them, it turned out, were armed with Browning Automatic Rifles [BARs] apparently captured earlier in the war. Mantini again let loose with his Thompson and hit all four. Three were dead, one wounded. He ran to the spot and saw that the wounded Japanese soldier, in his death throes, was trying to commit suicide with a grenade.

“I had already killed this one Jap maybe 5 or 10 minutes before I saw these snipers,” Mantini explains. “I was going down the hill when a flash hit me in the eyes, like a mirror. Here, it was one of the BARs that they had captured, probably taken earlier from our guys on Bataan. All the blueing was off it, and it was like a mirror. He brought it up to take a shot, and the flash hit me. I knew something was wrong, and I hit the dirt. He shot, but I was already behind a little knoll. I knew exactly where they were, and that’s when I whacked them out. When I got up to them, the wounded Jap was letting on like he was dead, but he was holding a grenade in one hand and trying to pull the pin with the other. So I stepped on his hand and he couldn’t pull the pin. Finally, I told this recruit to stab him in the throat. Blood squirted about three feet in the air. He was dying anyhow.”

The tunnels on Hill 522 were permanently silenced on the sixth day after the Leyte landings. Their openings were blasted shut with TNT or blocked with boulders and logs. Those inside either died by suicide or starvation. No prisoners were taken, and any wounded Japanese soldiers encountered by the Americans were killed. Taking the hill cost 1st Battalion 14 killed and 95 wounded. General Irving later commented, “If Hill 522 had not been occupied when it was, we might have suffered a thousand casualties.”

“We kept hopping from hill to hill until we secured the area,” Mantini says. “We had a heavy-weapons outfit attached to us, and when we got to the top of one hill there was a clear view out in front of us. It was a beautiful spot for a machine-gun position. So I said to the guys in charge, ‘You should set up your machine gun here. There’s a great view of the valley.’ They said they didn’t want to, so I told them, ‘Don’t come back and tell me you want it after I get the damn hole dug because you’re not going to get it.’ So I started digging, and I had a helluva time because there were big rocks. The hole was about half dug when these guys came back and said, ‘We’ve changed our mind.’ I said, ‘Don’t tell me you want it here, because you’re not getting it.’ One word led to another, and finally they threatened to see the company commander.

“I said, ‘Go see anybody you want, you’re not getting this damn hole.’ I was mad! So they went and saw the company commander. He called me up and said, ‘You know, Mandy, that is the best position for a machine gun.’ I said, ‘Look, I told the guys that but they didn’t want it. And now, after I got the hole half dug, they want it.’ I finally said to them, ‘OK, take the damn hole. I hate to do it but go ahead.’ About 10 minutes after those guys finished digging, there were three of them, we started getting shelled and one dropped right in the middle of that hole and killed all three.”

For the two sides battling for control of Leyte, no difference in battle techniques was as obvious as the timing of an attack. Daylight operations were usually the norm for American forces, while on the other side of the line the enemy preferred to wait until dark. They would either advance stealthily and suddenly appear out of nowhere or charge U.S. positions from out of the darkness, firing guns, throwing grenades, and screaming “Banzai!”, which they hoped would paralyze their enemy with fear.

Mantini’s Trusted Tommy Gun

This inspired eagerness to die was due in part to the Bushido spirit of the warrior, the feudal-military code of honor that had been instilled into Japanese soldiers for centuries. Honor, it taught, had a higher value than life itself. The ultimate irony, however, was that the soldier was dead. And dying certainly did not appeal to Mantini. That is why he felt comfortable with his Thompson and a 30-round magazine; 15 rounds weren’t enough, he says, and a 50-round circular canister got the bore of the gun too hot. He always tried to have six magazines on hand when going into battle.

“I was pretty sharp with a Tommy gun. I carried the same one all through the war. Wherever I went, it went. The stock was bent a little, but I wouldn’t let anyone touch it, and I kept it clean and in good shape. I carried a toothbrush, oil, and a rag in my upper pocket, and every time we stopped I cleaned it. Some people said a Thompson always jammed, but mine never did. And I told everyone in my platoon, if they wanted a Thompson, I’d get them one. I used to say, ‘If the enemy shoots one round, you shoot a thousand back. When you’re firing at them, at least they aren’t sticking their heads up to see where you’re at.’”

By the end of October the 24th Division’s fighting along Leyte’s coast had ended at a cost of 638 Americans dead, wounded, or missing. Its next target was the 35-mile-long, 10-mile-wide Leyte Valley, a peaceful place during the dry season, criss-crossed with slow-moving streams and home to numerous plantations that grew rice, bananas, coconuts, and papayas. During the rainy months, however, these same verdant fields were constantly flooded and the peaceful streams were turned into rivers. It was under such conditions that the division moved forward.

The 19th Regiment was ordered to take the town of Pastrana on the division’s southern flank and block one of two highways that led in and out of the valley. That objective was reached but only after heavy fighting, some of it house-to-house. Other smaller towns fell in rapid succession until the regiment faced the rugged mountains near Ormoc on Leyte’s western coast, where Japanese reinforcements were arriving, siphoned away from Luzon and Mindanao. It was here that Mantini’s company was picked to carry out a harrowing mission deep inside the enemy-infested jungle.

Drawing nine days of rations for 275 men, Company A left camp with Filipino guerrillas as guides, its mission to block the Japanese from using the old Spanish trail that linked several mountain passes with Lake Danao and to protect the division’s left flank. Mantini says the men probed far into the high passes made clear only by the use of machetes, while ammunition and supplies were limited to what each man could carry. The force hit its first obstacle—a Japanese machine-gun outpost—near evening of the first day. One Filipino guide and two of the enemy were killed in the encounter.

On the second day, the column ran into a larger Japanese force that was attempting to cross the mountains from Ormoc. The enemy was stopped, but many fled into the jungle. The company spent most of the third day cutting a path toward Lake Danao when, around midnight during a pounding rain, the Japanese attacked again. Some managed to break through the company’s outer defenses and charged with bayonets and grenades. This assault was also stopped, and at dawn 12 dead Japanese were found between the men’s foxholes. The fourth day of the mission was no different. Patrols encountered two more enemy outposts, and the results were the same. By this time, Mantini says he was fed up with the fighting, the low rations, and especially the environment.

“I was scabbed from my ankles to my knees by mosquitoes and ants. Leeches were another thing. We had to burn them off by holding a lighted cigarette about an eighth of an inch away from our skin until the leech fell off.”

Conditions for the men grew even worse over the next five days. More pitched battles ensued, and rations ran out. The GIs ate wild bananas and taro roots, which was somewhat ironic since the shoulder patch of the 24th pictured a taro leaf. Rain, which fell unabated, made life miserable and drenched foxholes with water and mud. Ponchos were the men’s only cover. During one fierce fight for a ridge top just before dark, the company was caught in a typhoon-like storm that made further fighting impossible. Mantini says they withdrew down a deep gorge and set up a defensive perimeter on a “nose” inside the valley that jutted out like an island. Minutes later, a roaring mountain of water surrounded the huddled company. Through flashes of lightning they saw trees being washed down the gorge mingled with the bodies of Japanese soldiers they had just killed in battle.

“You wouldn’t believe how high the water got in such a short period of time. It was only about 10 feet deep at first. Then all of a sudden it was about 30 feet and we headed for higher ground.”

When the company rejoined its regiment nine days after starting the mission, only 120 men were fit for duty. The others had been killed, or were wounded or sick from the physical strain and exposure to the elements.

Leyte was cleared of Japanese troops by Christmas 1944. The enemy’s last area of defense was on the island’s northwest peninsula where, in a final show of defiance and willingness to die, a horde of Japanese soldiers armed only with bayonets fixed to bamboo poles attacked strong American positions occupied by the 34th Regiment. Since the division’s landing on Red Beach 66 days earlier, an estimated 7,300 Japanese had died in battle; casualties for the 24th Division were 2,000 killed, wounded, or missing.

While the 34th was left behind to secure Leyte, the division’s other two regiments were picked to invade Mindoro, which was needed for airstrips from which planes could menace Japanese shipping in the sea lanes through the Philippines and provide air cover for the coming landings on Luzon. Unlike Leyte, portions of Mindoro’s interior regions were largely unexplored, and battle maps labeled these areas “unknown.” Mindoro did lack a sizable enemy force, as only about 700 Japanese, elements of the 8th Division, manned the island. On December 15 the 19th Regiment went ashore on the island’s southwestern tip near the village of San Jose. To their relief, the landing was unopposed because the few Japanese who were present fled inland when U.S. forces approached. Mantini, who by this time had made staff sergeant once again, encountered just one enemy soldier.

“Let the Guy Alone. If He Goes Through All That, He Deserves To Be Left Alone.”

“We came across this shack and there was this big, husky Jap inside of it, the biggest Jap soldier that I’d ever seen. So I emptied what was left in my clip on him and he was still standing, moving around. That’s when I saw a meat cleaver on a table inside the shack. I told someone to go in there and smash him in the head with it. You could see the inside of his head where it was split open, and the Jap was still standing, walking around. I think he was drunk. Another guy beside me had an M-1, and I said, ‘Put eight rounds in him.’ He did, and the Jap was still standing! Finally, when we were leaving I said, ‘Let the guy alone. If he goes through all that, he deserves to be left alone.’”

Although Mindoro was not manned by a large number of the enemy, U.S. troops still had a tough time of it, particularly on the beaches where they were bombed and strafed by Japanese planes on a daily basis. All of this attention caused concern that a Japanese counteroffensive was imminent, so the order was given to dig in and erect machine-gun emplacements. The men on the beach spent Christmas Day under such conditions.

“It was the worst Christmas of my life,” Mantini says. “Guys beside me were being blown up from the shelling. We were anticipating an invasion from the sea, but it never happened.”

It took four months of grueling effort for the Americans to clear Mindoro of enemy troops who were separated in the hills and were never able to organize themselves into a single fighting unit. Instead, they crawled into the mountains and became one-man terrors. This slow and frustrating progress is described in the following assessment made by General R.B. Woodruff, who replaced General Irving as 24th Division commander in November:

“Unlike Germans, if the Jap, when cornered, would surrender, he’d be immeasurably easier to fight. But he won’t. Tactically you first lick him, then you have to spend days, sometimes weeks and months, rooting him out and killing him. Long, miserable days in the jungles and mountains end by burning a few Nips out of caves with flamethrowers that have to be carried 20 miles on [someone’s] back.”

American frustration on Mindoro ended when Japanese opposition ended. Enemy losses were estimated at 600 killed, and in a rare occurrence 73 taken prisoner, two of whom Mantini captured himself.

“We were moving forward one day, and a Jap came out of a hole in the ground with a white handkerchief around his hand. I started to crawl toward him and told my men to shoot about a foot over my head in case there were more Japs and they tried to rush me. When I got near him, I asked, by pointing my gun toward the hole he had just come out of, if there were any more in there. Right then, another one came out and said, ‘Hi, ya.’ I asked him why he didn’t come out first, since he spoke English, and he said, pointing to the other Jap, ‘If you would’ve shot him, I wouldn’t have come out.’ I said, ‘How did you learn English?’ He said, ‘I went to college at the University of Southern California. When I got back to Japan they drafted me right away, so here I am.’”

Before Mindoro was cleared of the enemy, the Japanese had set up an artillery position on tiny Verde Island, located off Mindoro’s northern coast, and mounted on a height designated “Mickey Mouse Hill” because it was so small and bothersome to American naval operations passing through Verde Strait. The Japanese also operated a radio station there that reported on U.S. ships moving in the direction of Luzon, which had been invaded a month earlier.

Orders came down to eliminate the guns and radio station, so a small force from the 19th Regiment, guided by Filipino guerrillas, was sent on February 23, 1945, to remove the Japanese presence there. It was Mantini’s fourth island landing of the war, albeit smaller than the others. The men were dropped off in the darkness about a mile or two offshore, boarded small boats, and paddled their way in. The invasion site and the approach to the guns were to be marked by a light, signaled from Filipino fighters on the island.

“There are so many damn islands over there,” Mantini says. “The Philippines have more than 7,000. And that’s all it seemed we kept doing, hitting these damn beaches. When we went in on Verde, it was dark, darker than hell. We had to hold on to the guy in front to stay close to him. That’s how dark it was. We were supposed to see a light when we landed, a beacon, but it wasn’t there. I said to my buddy, ‘I think this is it. The damn light ain’t there.’ But after a little while it did come on, and we moved toward it.

“We had two Filipino guides with us,” he continues. “To me, the Filipinos look just like Japs. They’re hard to tell apart. I said to the commander, ‘Who are these guys?’ He said, ‘They know where the gun positions are that we’re supposed to knock out.’ I said, ‘I don’t know. These guys look like Japs.’ He told me they weren’t, that you can look at their eyes and tell a Japanese from a Filipino. But I couldn’t tell the difference, I never could. So supposedly the Japs captured these two guides who were leading us. We heard a helluva scream and the C.O. said the enemy got them both. I said, ‘If the Japs got them, then where the hell are their bodies?’ He said they took them. I said, ‘It smells a little fishy to me.’

Led Into An Ambush

“Here, two guys disappeared and we never saw them again. So he asked me, ‘What do you think we should do?’ I said, ‘Do you know where the guns are?’ He said no. I said that I didn’t know where they were either. He asked, ‘Which way would you go?’ I said, ‘You know where we came from, don’t you? And you don’t know where the hell we’re going, do you?’ Then he said, ‘You suggest we go back?’ I said, ‘Let me tell you something. We had better get moving because they’re going to drop a helluva barrage of artillery in here.’ No sooner had I said that than their artillery started coming down, but by then we were already near the water and out of range. I think the Filipino guides were actually Japs leading us up into an ambush.”

The force searched Verde over the next two days, fought several skirmishes with the enemy, and left local guerrillas in charge before departing. Mantini says they did find one big gun, but the Japanese removed a key part from it before fleeing. Several days later, the locals reported the gun was still in place, so another force, this time a mortar unit, arrived and permanently ended the Japanese presence on Verde Island.

Mantini’s final combat experience of the war took place on Mindanao, where the largest and last enemy stronghold in the Philippines, some 50,000 soldiers, was located after the fall of Manila. Isolated, these troops did not pose a threat to the progress of the war, but in keeping with MacArthur’s policy, ridding the island of their presence was necessary to liberate the Filipinos who lived there. Mindanao, like Mindoro, contained interior regions unknown to U.S. map-makers. But unlike Mindoro, it was also home to native tribes, such as the Moros and Manobos, whose allegiance was something of a question.

Leaving San Jose harbor on Friday, April 13, two regiments of the 24th (later reinforced by the U.S. 31st Division) went ashore four days later at the town of Parang on the shore of Moro Gulf on the island’s western coast. The choice of that invasion site completely fooled the enemy defenders, who expected any assault to come on the eastern side of the island where the bulk of the Japanese garrison was located.

Facing no opposition, the Americans gained a 35-mile length of coastline and easily progressed five miles inland by the end of the first day. High mountains, deep valleys, and about 50 streams and rivers separated the men from their ultimate goal, the city of Davao, 150 miles to the east. To reach it, 24th Division troops mainly followed the National Highway, a mostly one-lane road defended at various places by small but lethal Japanese outposts. Night ambushes were a common occurrence, and numerous types of booby traps hampered their march. The most devastating of these were the 500-pound aerial bombs, left over from the destroyed Japanese air force. The enemy buried these along the trail, and they were detonated with wires strung into the jungle.

Despite these hidden dangers, Mindanao was cut in half in less than two weeks. The force reached Digos on the island’s eastern coast on April 28 and found abandoned guns and pillboxes pointing seaward, indicating the Japanese had planned a strong defensive effort against any would-be invader.

Sinister Japanese Battlefield Tactics Outrage The GIs

The division now began its 40-mile drive north to Davao, where an estimated 10,000 Japanese were to perish in the coming months. If Americans thought the Japanese rules of warfare on Leyte were outrageous, more was in store for them on their march to Davao and beyond. In one scenario, a wounded American lay on the jungle floor. Nearby, a Japanese soldier would cry, “Medic.” When one rushed forward to help his stricken comrade, he would be shot. In another, a Japanese soldier would dig a foxhole near a trail, bury a mine in it, and then withdraw into the jungle. As Americans walked by, the Japanese would fire on them, forcing some into the foxhole where they were killed by the explosion. In still another scenario, a Japanese sniper would fire his weapon down a trail, intentionally revealing his position. With a patrol lured forward, the Americans would be caught by machine-gun fire from both sides of the path.

The effect of these sinister battlefield practices worked to fuel the fighting spirit of American soldiers like Mantini, which is reflected in the following dispatch written by an Army war correspondent at the time and published in Mantini’s hometown newspaper. The action took place when four companies of the 19th Regiment were making their way toward Hill 550, a dominating height overlooking Davao, which was heavily defended by pillboxes and other fortifications:

“With the 24th [Victory] Division on Mindanao—Staff Sergeant Angelo J. Mantini, a Kittanning, Penna., shoemaker, knocked out a 25mm “ack-ack” gun with his tommy gun and killed five Japs who manned it. Mantini’s company of this Victory Division’s laurel-crowned 19th Infantry Regiment was advancing toward a strategic hill near Davao. The lead scout was wounded by machine gun fire and Mantini took the lead. A Jap 25mm “ack-ack” gun opened up on them at close range. Mantini stood erect, blazed away at the Jap gunners with his tommy gun. The thirty rounds in his magazine plunged into the position, killed five Japs, and silenced the gun. According to his company commander, in the fighting on New Guinea, Leyte, Mindoro, Verde, and Mindanao, Mantini has killed more than forty Japs.”

“At that point my company commander said he was going to recommend me for the DSC [Distinguished Service Cross],” says Mantini. “I think his name was Hoy, but nothing ever came of it.”

American troops battled their way into the devastated city of Davao on May 2, 1945, and found its one-time civilian population of 90,000 reduced to only about a hundred inhabitants. Most had either fled into the mountains, perished during months of incessant fighting, or had been executed by the Japanese. Disease also claimed its share of the populace.

No respite was afforded the Americans after taking Davao. The enemy had moved its considerable number of artillery pieces beforehand to the relative safety of the surrounding mountains, and pounded the area on a daily basis. Japanese suicide charges continued as before but with a new and gory twist. On the second night of Davao’s occupation, enemy soldiers attacked, throwing grenades and firing weapons, but this time with land mines strapped to their stomachs. They made five successive “Banzai” charges at the center of town. American bullets detonated many of these one-man kamikazes. More than one company command post reported arms, feet, and heads raining down in the night.

Americans on Mindanao faced three more months of desperate fighting north and west of Davao city, where the area’s abaca plantations proved to be most menacing places to do battle. Called Manila hemp, the plant grows 15 to 20 feet high, providing the Japanese with a perfect place to ambush war-weary GIs who had to physically push their way through the close-grown stalks to flush out the enemy. They found the best method of locating Japanese positions was unfortunately the most deadly: Advance through the fields until they met gunfire.

This type of contact continued until U.S. warplanes began using napalm bombs to set many of the abaca fields on fire, a situation that only added to the tropical heat, which was also taking its toll on the men. Some companies at this time could muster only 70 men, their ranks depleted by heat prostration. Water was becoming more and more precious. Mantini remembers refilling his canteen more than once in swamps or water-filled bomb craters that contained dead Japanese soldiers. Two purification tablets placed in the canteen apparently made the water fit for human consumption.

Mantini’s Luck Finally Runs Out

After five island landings, months of tough jungle fighting, and never receiving a wound in battle, Mantini’s luck was stretched to the limit. It ran out on June 24 in his company’s last fight of the war, when he was injured under both arms by shrapnel from an exploding Japanese grenade.

“I was in action, shooting, when three grenades landed beside me. I was able to drop my gun and throw two back, but one landed to my right and I knew I couldn’t get to it before it exploded because you only have about four or five seconds. Right when I thought the grenade was ready to go off, I was turning to get away from it when the explosion caught me under my arms and ripped open my shoes and my pack. It caught me real good up under my arms. I made every drive the company made during the war, and that was the last one.”

Mantini was carried from the battlefield by a stretcher detail until he saw other GIs who were injured more severely, apparent victims of friendly fire. “Twenty minutes or so before I was wounded, I looked to our rear area and the coconut trees were moving back and forth, passing each other. I said to one of the guys, ‘Our planes are bombing our troops. Look at those coconut trees. The only planes in the air are ours.’ What happened was our planes bombed the hell out of the troops behind us. I got wounded a short time after that, and I was on a stretcher, going down, and our soldiers were lying all over the place. I said to the guys carrying me, ‘Let me off here. Grab one of those other guys. I’ll walk down.’ Infantrymen were lying all around.”

Mantini received the Purple Heart while in an Army hospital on Leyte, where he remained until the end of the war. “When I got out of the hospital and went back to my company’s headquarters, everybody there was new, even the company commander. He called me up and said, ‘We’re going to Japan for occupation duty. Do you want to go with us?’ I told him the only place I wanted to go was home. So I waited in the Philippines while men, supplies, and everything else were sent to Japan. I was stuck on Leyte. I couldn’t get out of there.”

Despite the American cease-fire ordered in mid-August, the killing on Mindanao continued for weeks afterward. Enemy troops, cut off from all communication in their jungle lairs, did not know it was time to quit, or refused to believe that Japan had surrendered. It was not until the Japanese commander, ill with malaria, was located and agreed to U.S. surrender terms, that the emaciated remnants of his command began to filter out of the countryside.

The 24th Division was sent to Japan for occupation duty at the end of September. Mantini, his point total high enough to gain a discharge, finally left the Philippines and arrived in San Francisco on November 27. He headed eastward by train without a penny in his pocket.

“My service record was on the move after I got wounded. They said they didn’t have it. It must have been sent to Japan because I wasn’t getting paid. Every time the train made a stop, guys would jump off and head for a liquor store. Everybody else had money to buy whiskey, and there I was broke.”

Mantini was discharged from the Army at Fort Knox, Ky., on December 14. During four years of active duty, Mantini had somehow escaped the symptoms of malaria until he arrived home.

“I got it after the war. My first Christmas back home I had it. First you’re sweating, then you’re freezing so bad that you can’t stack the blankets high enough. Then you’re sweating again. But I never had it over there. And it’s funny that I didn’t because they supplied us with pills [atabrine, a form of quinine] that made our skin yellow. That’s why I never took them. I didn’t want yellow skin. And as a platoon sergeant in combat, I was supposed to take the pill, stand in front of the men in the morning and be the first one to take it. But I would fake it. I got really good at it. I would hold the pill in my hand and throw it toward my mouth. It would hit right below my ear and fly away from me about 10 feet. I didn’t take it, but I had to make sure that everybody else in my platoon did.”

Now, nearly 60 years after the war, Mantini assesses his role with fondness for his comrades, similar to that felt by most veterans who have experienced the horrors of modern warfare.

“In combat, I think you’re better off in the infantry than in any other outfit. Guys would go like this,” he says, holding his hand above his head with his index finger pointed skyward. “I’d say, ‘What the hell are you trying to do?’ They’d say, ‘I want the Purple Heart to get out of combat.’ But then they’d laugh. They just did it for fun. Times like that made being in the infantry special. You’re in danger when you’re fighting, but I think it’s a better unit than any other. Everybody in the infantry is like a brother.”

Heck of an individual and a soldier, nothing but admiration and a salute.

The Hollandia landings in April of 1944 were not the first American operations on NG. American units were part of the defense of Milne Bay in August of 1942, and fought in the Buna-Gona campaign in late 1942 and early 1943.