By Allyn Vannoy

Lieutenant Robert Sabel struggled to get his Fortress, the Rusty Lode, home. Eight B-17s of his bomb group, the 390th, had already been shot from the sky. Sabel’s ship was riddled with flak and shell holes, two engines were out, and his fuel gauges indicated just two minutes of fuel remaining in his tanks. Three of his crewmen had bailed out over Germany; four others lay dead in the bomber’s radio compartment. The odds of even making it back to England were highly unlikely. Then he saw it—his field’s runway—just ahead.

As September 1943 drew to an end without a resumption of deep penetration raids by American heavy bombers, General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, commander of the U.S. Army Air Forces, became increasingly aggravated by the lack of initiative on the part of General Ira Eaker, Eighth Air Force commander. Based on the number of replacement bombers arriving in England, Arnold could not understand why Eaker wasn’t attacking Germany with at least 500 bombers on every mission.

Eaker had been feeding the new planes and green crews into the groups that had been badly depleted during the Stuttgart raid on September 6, when 388 B-17s had been sent to destroy the city’s industrial sector. A fifth of the force aborted due to weather or mechanical problems. Of the 262 B-17s that made it to Stuttgart, 45 were lost. After the raid, Eaker limited most of his targets to those in France, within range of his escort fighters.

On September 28, Arnold directed his staff to send a message designed “to build a fire under General Eaker.” Although Eaker focused on making good the loses sustained on September 6, in the face of Arnold’s pressure, he reluctantly prepared to resume the air offensive into Germany.

In early October, Eaker’s meteorologists forecast a week of good weather, and so Eaker directed the offensive be resumed in earnest.

On October 8, the Eighth Air Force dispatched the largest American raid to date, sending 399 bombers to strike the Bremen shipyards and industrial area and the U-boat construction yards at Vegesack, Germany, near the North Sea coast; 314 Fortresses reached their targets. German air defenses shot down 27 aircraft and damaged 217; 325 causalities were suffered. Two bombardment groups, the 100th and the 381st, each recorded the loss of seven aircraft.

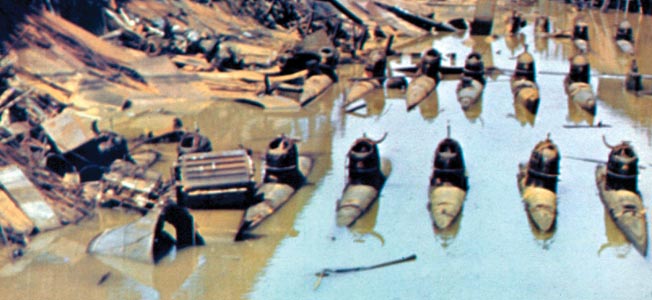

The next day, Saturday, October 9, 378 American bombers were sent on the deepest penetration raid yet flown, hitting targets in both Germany and Poland. The raid was the first time airborne transmitters were used to jam German radar. Targets included the Danzig U-boat yards and the port area at Gdynia, on the Baltic Sea. The force included a mix of B-24 and B-17 groups from all three bomber divisions.

Bombers of the 1st Bombardment Division—115 B-17s of six bomb groups—were also sent to hit the industrial area at Anklam in northern Germany. The 1st Division groups suffered heavy losses, with 18 B-17s shot down, 52 damaged, and 210 crew casualties. The 3rd Bombardment Division’s target was Marienburg, Germany, about 20 miles southeast of Hannover. The losses were light—just two bombers out of 100 assigned to the mission.

Eighth Air Force planners were determined to keep the pressure on the Reich on October 10. Weather forecasters predicted a large, high-pressure area that would bring clear skies to Germany. The plan involved all 16 B-17 heavy bomber groups—a total of 237 B-17s—plus 217 P-47 Thunderbolts in support, striking Münster, Germany, as well as targets of opportunity at Coesfeld, Germany, and the Enschede Airfield in the Netherlands.

A shallow and direct penetration raid to Münster would allow for escort fighters to stay with the bombers all the way to the target. The two B-17 bomber divisions would attack the center of the city in a single stream, while a fewer number of B-24s would fly a diversion over the North Sea in an effort to draw German fighters from northern Germany.

On the night of October 9, the “Alert” message came down from “Pinetree”—code name for the Eighth Air Force Headquarters at High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire—detailing the mission to Münster, just 35 miles from the Dutch border, a historic city with a population of 155,000.

The aiming point for the strike was to be Münster’s 1,000-year-old cathedral. Within the city was a sprawling railway marshaling yard. American planners calculated that the entire German rail system operating in this heavily trafficked area would be seriously disrupted as rolling stock and a key operations center were destroyed along with train crews and maintenance-and-repair personnel.

The bomber crews were told that their target was strategic; that they would be attacking the workers of one of the largest railroad switching yards serving the industrial Ruhr. This was the first time the Eighth Air Force had specifically targeted civilians.

For their part, the Luftwaffe assumed that the Eighth Air Force would return to Germany on the 10th, and so they shifted additional fighter units forward to Dutch bases on the 9th. On the morning of the 10th, the increased volume of radio traffic from the American bomber bases signaled a massive raid.

When the bombers did not take off during the early morning hours, as they normally would for a deep penetration raid, the commander of Luftwaffe fighters at Deelen, the Netherlands, concluded that the bombers were headed to northwestern Germany and began to deploy his forces accordingly. The largest group was placed within 25 miles of Münster at Loddenheide and Münster-Handorf. Heavy anti-aircraft guns defended both airfields, the city itself, and numerous military installations around Münster.

German radar stations detected the American bombers as they began stacking up over East Anglia.

Major John Egan, 418th Squadron, 100th Bomb Group, was to lead his squadron on the Münster mission. Egan said, “The mission had not been set up for one to kill the hated Hun, but as a last resort to stop rail transportation in the Ruhr Valley. Practically all of the rail workers in the valley were being billeted in Münster…. A good, big, bomber raid could really mess up the very efficient German rail system by messing up its personnel.”

At the group’s mission briefing, its intelligence officer, Major Miner Shaw, informed the crews that the mission would take them across the Netherlands to the railroad yard at Münster, just over the Dutch border. As a short raid, P-47 fighters would escort the bombers to the limit of their range. Six Thunderbolt groups were to provide escort for the bombers—three groups to rendezvous on the way to Münster and three for the return leg.

Many bomber crews that had seen friends lost in the previous days cheered the opportunity to kill Germans. Other aircrews were surprised to learn that they were to bomb civilians as their primary target. As a result, some were not inclined to fly that day.

Colonel John Gerhart, commander of the 95th Bomb Group, addressed a reluctant officer: “We’re in an all-out fight; the Germans have been killing innocent people all other Europe for years. We’re here to beat the hell out of them … and we’re going to do it.” Gerhart would be the task-force commander, occupying the co-pilot’s seat of the B-17 The Zootsuiters.

Bombardier Lieutenant Jack Nosser of Cash and Carrie, 390th Bomb Group, responded to the briefing: “Even saying we would bomb only military targets, there were factories and plants situated in cities and towns anyway, and with a whole Air Division of perhaps nine or 10 Bombardment Groups all attempting to hit a specific point accurately from an altitude of five miles, and with cross winds gusting up to more than 100 miles an hour, errors were bound to occur.”

Opinions of the bomber crews varied. Sergeant John Leahy, a radio operator with the 385th Bomb Group: “I was exhausted and completely drained emotionally. I assumed that we were continuing our strategic bombing of military targets. By then, of course, we were living on borrowed time—our crew was on its nineteenth mission…. I didn’t expect to complete my tour.”

Opinions of the bomber crews varied. Sergeant John Leahy, a radio operator with the 385th Bomb Group: “I was exhausted and completely drained emotionally. I assumed that we were continuing our strategic bombing of military targets. By then, of course, we were living on borrowed time—our crew was on its nineteenth mission…. I didn’t expect to complete my tour.”

For many of the crews it was the third mission in as many days, and so most were too tired to care one way or the other.

Lieutenant Howard Hamilton, bombardier of the 100th Bomb Group’s M’lle Zig Zag: “The basic problem in trying to bomb a railway system is that, if sufficient labor is available, railroad tracks can be repaired in short order. We were told that the idea of bombing these railroad workers’ homes was to deprive the Germans of the people to do the repair work.”

Among those with the 385th Bomb Group at Great Ashfield, Lieutenant William Whitlow, who had piloted the long, tiring mission to Marienburg, thought: “Give me a short, hot mission to the long, dreary one any time.”

Captain Frank Murphy, navigator of the 100th Bomb Group’s Aw-R-Go, recalled: “Compared to over 11-hour deep penetration into German airspace to distant Marienburg the previous day, which I flew in the 100th’s lead B-17 with our commanding officer, Colonel “Chick” Harding, Münster, which is just beyond the Dutch/German border, didn’t appear to be a particularly alarming or hazardous mission at that time.”

Lieutenant Keith E. Harris of the 570th Squadron, 390th Bomb Group, had flown missions to Bremen and Marienburg. On the morning of the 10th, Harris learned that his crew was assigned a new B-17G, Stork Club, but that they were also posted to the 100th Bomb Group. The 100th had already gained a bad reputation that had begun with the raid on the aircraft factory at Regensburg on August 17, when it lost nine B-17s.

Lieutenant Harris appealed to his commanding officer, Colonel Edgar Wittan, informing him that he didn’t want to fly with the 100th. Wittan told him that everyone was going on the mission and that the 100th was short of planes, that they needed enough to complete their group.

At 11:11 a.m., the lead B-17 of the 100th, M’lle Zig Zag, lifted off the runway at Thorpe Abbotts, 106 miles northeast of London. The 100th Bomb Group was only able to put 12 planes in the air instead of the required 18 to 21, having lost seven aircraft two days before on the mission to Bremen. Six to nine aircraft were to be supplied by other bomb groups, but the full number failed to appear.

Lieutenant Harris and one other aircraft of the 390th took off and flew to the 100th assembly area. But the other Fortress of the 390th had problems, either real or imagined, and returned to base.

A worrisome sign appeared early as Lieutenant Paul Vance, 390th, spotted a lone German Me 110 at high altitude observing the groups as they formed up.

The 53 bombers of the 13th Combat Wing (95th, 100th, 390th Bomb Groups) assembled over Great Tarmouth, then headed southwest to join the other combat wings of the 3rd Bomb Division, the 4th Wing (94th and 385th Bomb Groups) and the 45th Wing (96th and 388th Bomb Groups), both of which trailed the 13th as it turned east. A total of 247 B-17s and 216 P-47s were dispatched.

The 3rd Bomb Division began crossing the English coast at Felixstowe on schedule at 1:48 p.m. It was followed 15 minutes later by the 1st Bomb Division, which was assigned most of the P-47 escorts with the expectation that the 3rd Division would achieve surprise; the two divisions formed a bomber stream 75 miles long. Over the North Sea, four bombers of the 100th turned back, claiming mechanical difficulties.

Two of the Luftwaffe’s five divisional headquarters lay in the area of the strike—at Deelen in Holland and at Stade on the lower Elbe in northwestern Germany. The centers plotted reports from radar stations, then flashed messages to the airfields. The Luftwaffe began massing its fighter defenses.

At 1:23 p.m., a half hour before the American bombers had crossed the English coast, Luftwaffe controllers at Stade alerted their fighter units. Orders were sent to the twin-engine fighters based in the Low Countries and western Germany at 1:54 to ready themselves. An estimated 350 fighters would ultimately engage the Americans—Messerschmitt Bf 109s, Focke-Wulf 190s, twin-engine rocket-firing Me 110s, Me 410s, and Junkers 88s. There was even the appearance of rocket-firing Dornier 217 medium bombers.

At 2:05 p.m., two groups of Fw 190s took off from Deelen; a few minutes later two more departed the airfield at Rheine, north of Münster. At 2:08, three squadrons of the Bf 109s were on their way to the Dutch coast. The Me 110 squadrons at Stade were airborne at 2:15. Ten minutes later, another three Me 110 squadrons departed the field at Leeuwarden in northern Holland.

The German pilots were prepared. Fighter pilot Feldwebel Gerd Wiegand recalled, “Each B-17 had 12 heavy guns which could fire accurately and score hits at a range of 600 meters. When we attacked the formation of from three to six Flying Fortresses, it meant that we had to fly through the fire from anywhere between 36 and 72 guns to make an effective attack, often closing to within 200 meters or less, in order to get enough strikes sufficient to shoot down a B-17.”

As they started to cross the North Sea, a bomber of the 100th turned for home, and Lieutenant Harris pulled up into the lead of the high squadron.

As the bombers passed high over Schouwen Island, flak rounds began to burst ahead of them. Shortly after crossing the Dutch coast, three squadrons of P-47s of the 352nd Fighter Group rendezvoused with the 3rd Bomb Division. One squadron flew top cover, the other two took up position on either flank of the bombers as they cruised at 155 mph.

In the 2nd Bomb Division, when the lead B-24 had equipment problems and turned back, the rest of the division followed. The diversion of the division’s 39 B-24s had failed, freeing up more German fighters.

The German pilots began to concentrate along the track of the bombers. As the bombers crossed the Dutch border, passing over Westphalia, they ran into intense flak.

Captain William Lindley, a member of the 95th’s The Zootsuiters, noted, “Well before we got to Münster, the flak guns began putting up heavy barrages of antiaircraft fire over every city and town along our flight path…. The radar-tracking guns were by far the most accurate. We could, however, still give the flak gunners fits of apoplexy.

“By looking over the side of the cockpit at the gun emplacements, we could see every time the battery fired in unison [a battery salvo]. A slight turn in either direction [by the formation] of a few degrees and the 88 mm shell bursts would appear off to the side of our formation. The next time they fired a salvo we would begin a slight turn in the opposite direction. Radar tracking, with manual feed to the guns, made this maneuver possible. [But] you didn’t use the maneuver during the bomb run from the initial point to the primary target.”

The first enemy fighters to approach were easily driven off by the P-47s of the 352nd; however, the Thunderbolts reached the limit of their fuel at 2:48 p.m. over Dorsten, Germany, and had to turn back. The escort relief, the 355th Fighter Group, was fogbound at their airfields in England. Even after the aborting of 14 B-17s of the 13th Wing and 13 bombers from the other four groups of the 3rd Air Division, the division’s remaining 120 bombers continued on without fighter escort.

Luftwaffe pilots saw their opportunity. The bomber crewmen of the 13th Bomb Wing could only watch as some 200 German fighters prepared to make their attack.

The Luftwaffe employed new tactics and weapons, concentrating their attacks on only a few bomber groups in order to maximize the number of kills using swarms of single-engine fighters and rocket-firing twin-engine aircraft that flew out of range of the B-17’s guns.

Captain Rodney Snow, 95th Bomb Group pilot, recalled the fighter attacks: “They elected first to take on the 100th Group, which was flying low group in the wing. On the first pass, I remember there were eight to ten Me 109s, 410s, and Fw 190s coming in waves directly through our formation in a frontal attack from 12 o’clock level. Following their first pass, which took out three airplanes from the 100th’s lead squadrons, I thought that the enemy had successfully shot down all of our 100th Group—certainly most of them were smoking or had exploded in midair due to direct hits.”

Captain Murphy, the navigator on Aw-R-Go, said, “The German aircraft came after the 100th in seemingly endless waves. As one element of fighters broke away, another was turning for a head-on attack far ahead of us, and still others were forming up. Fighter after fighter flew directly into our formation, passing by so close that we could distinctly see the German pilots in their cockpits…. The fighters came on, at tremendous closing speed, with complete disregard for the curtain of defensive fire from our guns…. Exploding cannon shells ‘walked’ through our formation.”

The Luftwaffe had never before repulsed an Eighth Air Force strike. Robert “Rosie” Rosenthal, 100th Bomb Group, said, “I think this attack was aimed at turning us back for the first time.”

The 100th was starting to come apart. Shackrat, piloted by Lieutenant Maurice Beatty, leading the second element of three aircraft in the low squadron, suddenly exploded over Xanten, west of Haltern. Only two parachutes were seen.

Lieutenant Nosser of the 390th recalled: “Before we reached the initial point, I had seen Paul Vance’s Miss Carry take a direct flak hit just after the heavy fighter attacks had begun. It appeared to me that part of the left side of the cockpit had been blown completely away, and I vividly remember seeing Lieutenant Vance lying slumped across the lap of his copilot. It was all over in an instant of time, but his ship continued holding formation

We ended up at the rear of the formation, where we received the brunt of the fighter attacks. We were now in a hell of a lot of trouble.”

Nosser described the sounds of the attacks: “The screaming supercharger, the 20mm fire from the fighters sounding like gravel thrown on a tin roof coming in waves along the fuselage, the deafening din of all our own point-five’s firing, and the constant roar of our two good engines running at advanced power settings. At times, the vision from the nose was obscured by exploding shells. Why Cash and Carrie wasn’t blown into a thousand pieces, I shall never know.”

As the 13th Wing passed above Haltern-am-See, southwest of Münster, and reached the initial point (IP), nine minutes from Münster, a swarm of Fw 190s began level attacks on the 100th Bomb Group from dead ahead. The Focke-Wulfs came on firing cannon and machine guns, closing to 50-75 yards before flipping onto their backs and diving away.

Waist gunner of the El Paapanen, Sergeant Raymond Manley, 100th Bomb Group: “I was shooting at a 190 at nine o’clock and pieces started to come off him when a small glare to the right suddenly caught my eye. A rocket had apparently struck our left wing, igniting the main gas tank, and our number one port outer engine was also on fire. I called the pilot on the intercom to tell him, and he immediately banked the airplane steeply to the right out of the formation and dived. He side-slipped in an effort to extinguish the flames, but the fire grew in intensity.” Some of the crewmen were able to bail out.

At the IP, the task force commander’s Fortress, The Zootsuiters, made a gradual turn onto a course of 57 degrees, leading the badly mauled 13th Combat Wing toward Münster, 30 miles to the northeast.

Captain Lindley: “Flak increased as we made our turn over the initial point, and two more B-17s went down. It was about then that our number-four engine took a light hit and began to vibrate. Colonel Gerhart reached over to push the ‘feathering’ button to number four, but before he could press it, I knocked his arm away. A feathered engine at that critical time would have played all hell with the formation and the bomb run.”

1st Lt. John K. “Jack” Justice, piloting Pasadena Nena, 100th Bomb Group, had completed 17 missions prior to Münster. Justice recalled, “We were over Germany and had been under attack for some time when the group leader was hit and caught fire. The pilot performed the prescribed procedure of putting his nose down and getting away from the formation. His wing man, according to procedure, should have taken over the lead formation. Instead, all five ships in his squadron followed him down, leaving our squadron with three aircraft and the high squadron with three aircraft. The Germans immediately came in at all of us and split the remaining formation all over the sky.”

As they turned at the IP, Lieutenant Harris spotted two fighters approaching from about six o’clock; they shot up the lead plane of the group. It began to slow down, and as it did, it caused a disruption of the other planes. One of the most difficult parts of formation flying was the slowing down—if the lead slowed, it took a little while for the other planes in the formation to keep from overrunning it.

As the damaged B-17 started losing altitude, Harris attempted to hold his position in the formation and stay with him. While this was happening, German fighter attacks grew even more fierce, coming in from all sides. After Harris’s formation lost 2,000 to 3,000 feet, the 390th Group passed by above them.

About that time, the 100th’s lead plane was smoking badly, as the other planes tried to maintain formation, though scattered a bit by enemy fighters and the slowing down of the lead plane.

Harris: “Things then got very confusing in a hurry. The ships that were left milled around trying to form up on a new leader while under extremely heavy fighter attacks.” Harris realized he had to take action, and so gave power to the throttles and moved to catch the 390th. The B-17 on his right wing, piloted by Lieutenant Rosenthal, stayed close. During the effort to gain altitude, the two planes successfully fought off several fighter attacks; however, most of the German attacked seemed bent on finishing off the 100th.

By the time they reached the 390th, that group had already turned right, then made a slight turn to the left as it approached the bombing run. During the turns Harris and Rosenthal were able to catch them. Harris dropped into the number five spot in the low squadron.

Captain Charles Cruikshank, pilot of Aw-R-Go, recalled, “I was leading the second element of three airplanes behind the group leader’s element when he was hit and left the formation. I immediately took over the lead and continued the route as briefed. Apparently we were the only three ships left. Fighter opposition was extremely heavy at this point, and it continued all through our bomb run to the target.”

Within minutes any organization of the 100th Bomb Group had disappeared. Six B-17s were shot down and six others turned back with smoking engines. Only one of the 13 B-17s dispatched by the group was able to continue.

The only escort unit present, the 4th Fighter Group, was with the trailing 1st Division, in which just one bomber was lost. The main air battle was far ahead of them.

In Münster, the city’s inhabitants were enjoying a sunny Sunday afternoon. Assurances had been given by Home Air Defense that the Americans wouldn’t attack on a clear, cloudless day.

Carl-Friedrich Bell, a 17-year-old student, recalled, “During the air raids we all had to help in the defense of Münster. Our battery consisted of six 8.8cm anti-aircraft guns emplaced in a large, reinforced concrete structure with sloping earthen banks situated on the northern outskirts of the city. Our battery was crewed by 40 regular soldiers, 60 air-defense helpers—16- and 17-year-old boys mostly—and 20 Russian Powys…. We students were given such tasks as fuse setters, gun layers, and range-finding.”

Otto Schute, a 15-year-old apprentice at a Münster publishing firm, said, “Many times previously the sirens had sounded. When the ‘all clear’ had followed a little later on, we had neither seen nor heard any unfriendly planes. We concluded that nothing at all would happen and that the alarm had sounded because a few enemy aircraft were perhaps on their way into Germany, maybe well to the south or north of us. Nobody was worried about an attack on Münster…. We could not remember any large-scale air raid which had taken place anywhere on a Sunday afternoon in northwestern Germany.”

As they started their bombing run, one B-17 pilot described the sky over Münster as “A fantastic panorama of black flak bursts, burning and exploding B-17s, spinning and tumbling crazily.”

Sergeant Henry Glenden, top turret gunner of Miss Carry, observed that it was like flying through an aerial junkyard. The air was full of parachutes and falling men. The ship’s tail gunner, Sergeant William “Ike” Adamson, watched the enemy fighters approach: “The German twin-engines would fire rockets into our formation, and we would fan out to let the rockets pass. We could see them coming from way back, and I’d instantly relay their trajectory to our pilots up front and they would take evasive action.”

At 3:03 p.m., just three minutes behind schedule, the bombardier of The Zootsuiters released his lethal load of 500-pounders, and the other 18 B-17s of the 95th following suit. Forty seconds after release, the first bombs struck the heart of Münster. Moments later, the 16 Fortresses of the 390th Group unloaded their bombs.

Lieutenant Charles Walts, piloting Invading Maiden, 100th Bomb Group: “We had dropped our bombs and made the turn back towards England when we were hit again by both flak and fighters … Lieutenant Cooper Wilson, our bombardier in the nose compartment, was killed by a 20mm shell, and I was wounded by flak. The control column suddenly became unresponsive. I subsequently lost control, and the aircraft immediately went into a spin.

“With absolutely no response from the controls, I gave the order to bail out. Apparently, a following B-17 in what was left of our formation, under intense attack, had temporarily lost control, and one of its propellers had sheared off our tail section.”

On the ground, Otto Schute remembered: “As the bombs dropped closer and closer, and as the attack grew in intensity, we suddenly realized that our lives were at stake. We all started to scatter and race for cover as the bomb explosions and anti-aircraft fire reached a crescendo. I simply sprawled face down on the ground. Looking upwards I saw, to my horror, bombs and phosphorus canisters coming down—and it looked like they were all coming directly towards me. But they exploded 30 to 50 yards away.”

Fourteen-year-old Hildegard Kosers recalled, “The mournful wailing of the air-raid sirens mingled with the deadly whistling of the descending bombs. They exploded massively all around us: the earth shook, vibrated, shuddered, and heaved from the impact of the concussions. The solid concrete bunker trembled and shook to its very foundations.”

Gerhard Ringneck, a soldier on his way to the Russian front, was at the Münster railway station. He said, “Apparently a daylight raid on Münster had never happened before, and the local people were not taking the wailing sirens seriously as they nonchalantly strolled in the warm afternoon sun. Very soon I saw the first units of the bomber formation in the distance coming straight towards Münster.

“They were being attacked by many of our fighters, and, as they got closer, I could see bursts of anti-aircraft fire from our flak guns south of the city engaging the bombers. Then I saw two or three burning planes diving down out of control. It quickly became apparent, however, that the enemy bombers were not being stopped or diverted by our air defenses. Being such a clear day, I could see many more bomber units appearing in the distance, all heading directly towards Münster.”

Attacks on the 3rd Division alternated between head-on passes by Fw 190s and Bf 109s and rocket barrages from the rear by Me 410s and Me 110s. The German fighters broke off their attacks as the bombers approached Münster’s flak defenses, then resumed them as the 3rd Division left the target area. Four more B-17s were lost by the 95th Group. As the leading wing appeared to be on the verge of annihilation, the P-47s of the 5th Fighter Group arrived to deal with the German fighters.

Captain Rodney Snow, 95th Bomb Group: “Our bomb run was nearly six minutes—two minutes longer than we liked to fly straight and level as enemy anti-aircraft fire was quite heavy, as were the fighter attacks…. After they had practically destroyed the 100th Bomb Group in the low position of our wing, the fighters next concentrated effort was on the 390th Bomb Group, who were flying at about a 1,000 feet above and behind us. Here again, they took their toll with straight, head-on attacks against the three squadrons of the 390th.”

One of the few remaining 100th Bomb Group Fortresses, Forever Yours, piloted by Lieutenant Edward Stork, was seen to slowly keel over on fire and plunge earthwards. Barely 48 hours earlier, Stork had brought his B-17 home from Bremen on just one engine. Eight parachutes were seen.

Waist gunner Sergeant Stanley Smith of the 390th’s Stork Club recalled, “There were bandit targets all around the clock at this stage as we stood back-to-back, our feet slipping on the rolling clutter of spent cartridge cases while we tracked our separate targets, or relayed them to each other as they darted over and under our ship.”

As the Fortresses flew west from Münster, the German fighters continued to attack ferociously. The guns of Keith Harris’s B-17 seemed to be firing continuously. At one point a fighter came head on at 12 o’clock level. Harris noted that the fighter wasn’t firing. Just before colliding, the fighter dropped down slightly and Harris pulled back on his controls and raised his aircraft a bit, avoiding collision.

While this joust was in progress, the 390th lost two more planes to flak or fighters.

Harris responded by moving to the number four spot in the low squadron. Twenty minutes later over the Netherlands, as American P-47s appeared, the German fighters turned away, but not before another 390th bomber in the low squadron went down. Harris then moved up to the number-three position in the squadron.

Lieutenant William Oversteers, co-pilot of Situation Normal, 95th Bomb Group, said, “Münster was our crew’s 13th mission and it was, by far, the roughest. The Germans hit us with everything they had. The whole sky was a fantastic panorama of black flak bursts, burning and exploding B-17s, spinning and tumbling crazily … German fighters blowing up and going down streaming flames and long plumes of grey and black smoke.”

Departing the target area, Lieutenant Robert Schneider, a pilot with the 100th, witnessed a terrible event: “What little was left of the 100th Bomb Group’s formation was flying low and to our left. Shortly after bombing the primary target, two of their ships collided with an Me 109.” One of the Forts involved in the collision was Sexy Suzy—Mother of Ten and the other was Sweater Girl, piloted Lieutenant Richard Atchison. Six crewmen managed to parachute safely from Sweater Girl.

There were now only four 100th Bomb Group B-17s left, apart from Harris’s re-assigned air-craft: Captain Cruikshank’s Aw-R-Go, Lieutenant Rosenthal’s Royal Flush, Lieutenant Justice’s Pasadena Nena, and Lieutenant John Stephans’ Stymie. Moments later, Captain Cruikshank’s B-17 crashed near Linden, 15 miles from Münster. Then Aw-R-Go followed.

As Luftwaffe pilot Feldwebel Wiegand climbed to altitude, he noted, “What an awe-inspiring sight … their whole armada was laid out in front of me. About 20 olive-green camouflaged Fortresses flying in precise formation with their big white stars and glittering machine guns as they fired long streams of violet-colored tracer bullets at us from long range.”

Selecting a B-17 at the rear and on the left of a box, Wiegand continued, “I had him in my gunfight and I aimed at his left wing. I wanted to hit his engines. My guns thundered and immediately big chunks of metal came away from his left outboard engine. I then had to throttle back sharply to stay behind the B-17.

“Suddenly, from somewhere near the tail of the Fortress, a brown object came hurtling at me, barely missing my whirling propeller and passing within inches of my cockpit. A human body…. My B-17 [target] was now hanging on its two propellers in a 45-degree climb—the other two engines were gone. Suddenly it stalled and plunged towards the ground.”

The top gunner/flight engineer of Royal Flush, Sergeant Clarence Hall, recalled: “We were hit by fighters, mostly 109s, coming out of the sun in flights of five or six at a time from topsides. They cut right through our formations, seemingly taking out a B-17 on every pass…. At one stage, the fighters seemed to be going down like flies all around us. We claimed 15. It was more a nightmare than reality.”

Lieutenant Paul Perleful, a pilot with the 95th: “I vividly recall seeing a B-17 which had been simply cut in two halves by the concentrated cannon fire from a German fighter … [it] appeared to me to happen in slow motion. The Fortress was struck and slowly came apart at the radio room. The front half of the fuselage, wings, still-functioning engines, and the cockpit seemed to slowly rise upwards, completely separate from the rear fuselage and tail unit. Then both halves twisted and tumbled down and away.”

The 13th Combat Bomb Wing had penetrated the target area with 49 or 50 B-17s. Only 24 remained, some having sustained severe battle damage, as they withdrew towards the Dutch coast.

Rocket-equipped Me 110s were directed to intercept the 13th Combat Wing as it withdrew. Thirty-five Me 110s approached from aft of the bombers, and from 800 yards they loosed a salvo of 21cm rockets into the formation. The rockets, each weighing 240 pounds, contained an 80-pound warhead with a time fuse set to four seconds. The 110s were equipped with a graduated sight that indicated the span of the B-17 at different ranges.

The B-17 Tech Supply, 390th, piloted by Lieutenant John Winna, Jr., took a direct hit and exploded. Miss Fortune, in the 390th’s high squadron, piloted by Lieutenant Wade Sneed, received a rocket hit and broke in half. The front half nosed up and collided with a B-17, Miss Behaving, flown by Lieutenant George Starnes. Only one crewman survived from Miss Behaving. The other B-17s in the high squadron maneuvered frantically as they tried to avoid the exploding Forts, wreckage, and bodies hurled in every direction.

Heinz Hassling, a teenaged Luftwaffe helper with a flak battery protecting the Dortmund-Em Canal bridges north of Münster, recalled, “As they flew over, about three kilometers to the west of our position, a Fortress suddenly exploded … I could clearly see the wings, engines, and fuselage slowly disintegrating in mid-air. Seconds later, another Fortress, in the immediate vicinity of the first B-17, also exploded and seemed to fly apart.” These were likely Miss Fortune and Miss Behaving of the 390th Bomb Group.

Another 390th Fortress, Eightfold, flown by Lieutenant William Cabral, had its right wing almost torn off by a rocket during a frontal attack by an Me 110.

Lieutenant James Goff, navigator aboard the 95th’s Rhapsody in Flak, remembered the scene: “It all seemed like a blurred nightmare … wave after wave of enemy fighters … pieces of aircraft littering the clear blue sky … ugly black smoke of flak bursts, men in drifting parachutes … burning bombers and fighters all around us … 25 minutes that lasted an eternity.”

The 56th Fighter Group took off in poor weather at 2 p.m. to rendezvous with the bombers; however, it couldn’t prevent the loss of four additional 13th Wing Fortresses. The crew of Bad Penny, flown by Lieutenant Edward Weldon, 390th, was on its 18th mission when it went down near Divestiture, north of Münster. Patsy Ann IIWI, of the 95th, piloted by Lieutenant William Buckley, made a slow curve away from the formation with both wing fuel tanks ablaze and fire in the radio room. Over Holland, the ship of Lieutenant Frank Ward, Pinky, had to be abandoned—the eighth 390th Bomb Group Fortress to go down.

The trailing 1st Air Division had also had several aircraft abort, primarily because of excessive drag from externally mounted 1,000-pound bombs, one under each wing, which caused over-heated engines in several B-17s. A number of planes had to jettison these bombs over the North Sea.

Leading the 1st Division was Captain Sterling Baseler, 92nd Bomb Group. Six miles short of Haltern, a flak burst struck Baseler B-17, forcing him to veer his aircraft to the left while his navigator desperately tried to locate Haltern, the mission’s IP.

The maneuver caused the 14 Forts of the 92nd and the two following groups of the 40th Combat Wing to follow Basler’s turn. The wing was now on a course to Coesfeld, 20 miles west of Münster.

The 92nd and 306th Bomb Groups of the 40th Combat Bomb Wing, leading the 1st Air Division, bombed Coesfeld at 3:11 p.m. The third Group in the Wing, the 305th, realized the error during the bomb run, bypassed Coesfeld, and made a gradual right-hand turn to attack the primary target, Münster.

The next wing, with the 91st, 351st, and 381st Bomb Groups of the 1st Air Division, had formed a composite group of three squadrons en route, totaling only 16 aircraft due to several aborting B-17s—the wing having departed England with 27 Fortresses. As the 1st Combat Wing approached Münster from the IP, it found itself on a collision course with the 305th approaching from the northwest. A disaster was averted as the 13 B-17s of the 305th veered away at the last moment.

At 3:17, the 1st Combat Bomb Wing released its load of high-explosive and incendiary bombs. Feldwebel Alois Slaby, radio operator-gunner of an Me 410, recalled, “We then sighted a formation of B-17s while we were southeast of the burning city. Leutnant Stehle [the aircraft’s pilot] then maneuvered into position behind the bombers and opened fire. Dense smoke immediately poured from the B-17 and, as we emerged from the clouds of smoke, there were bombs over, under, and in front of us. Suddenly it was raining bombs all around us and the air was full of metal.”

About the same time that the 1st Wing was bombing Münster, two of the three groups of the 41st Wing (384th and 303rd), bringing up the rear of the 1st Air Division, released their bombs on a now-blazing Coesfeld.

There were only two bomb groups that had not yet found a “target of opportunity”—the 305th and the 379th. The lead navigator of the 379th, Captain Joseph Wall, thought that he had identified the town of Rheine, in northwest Germany. Post-strike photos revealed that the Dutch town of Enschede had been bombed instead, killing 151 civilians.

Lieutenant Justice, piloting Pasadena Nena, noted, “We found ourselves completely alone. I observed a group to our left returning from the target area. They were some five or six miles away and lower, so we dove to meet them and joined their formation taking a position between all three squadrons. It was a presumably safe place and we headed homeward. Shortly, a Jerry attacked this group and was aiming, I am sure, at the lead aircraft. Instead, he hit our No. 4 engine with a 20mm shell, which completely knocked it out and sent us in a fast spin.

“From approximately 20,000 feet, John, the co-pilot, and I tried to pull the aircraft out of the spin. At about 5,000 feet we succeeded, but the aircraft was still in a dive. John and I continued to try to right the aircraft and leveled off below 1,000 feet, at which time it was apparent that the rest of the crew members had parachuted out. We counted seven chutes, and John tried to stop the engineer from going out the bomb bay, but he could not hear him and abandoned the aircraft.

“John and I decided to head for home, crew-less and crippled. The No. 4 engine was still on the aircraft, but there was no cowling all the way back into the wing. We were able to control the aircraft and John decided to take up a position in the upper turret, to protect us from any further attack. We had no communication, so it is my supposition that John, upon entering the turret, saw a German following us down and turned the turret to take aim. The German seeing the turret move, realized that there was still life aboard and sprayed us from one wing tip to the other with 20mm shells. Both wings were completely on fire and the whole side of the cockpit, my side, was blown away.

“John, realizing our situation, came forward from the upper turret. There was blood across his forehead. He reached under my seat, handed me my chute, then put his on and went out through the bombardiers’ hatch. I put on my chute and went out the bomb bay…. To the south of me, approximately one mile, the aircraft crashed.”

Of the 13 planes of the 100th Group that took off for Münster, only one, Rosie’s Riveters, returned. Those on the ground who waited for the group were shocked to see a lone battered Fortress return. One-quarter of the 100th Group, 120 crewmen, were lost. Rumors circulated that the Luftwaffe was out to get the 100th. The Group had arrived in England four months before the Münster raid with 140 flying officers; after Münster, only three of them remained on flying status.

In the 45 minutes that the Eighth Air Force pounded the city, the 13th Combat Wing lost 25 planes. A total of 30 B-17s were lost from the raiders, 102 were damaged, three damaged beyond repair; casualties were two killed, 18 wounded and 306 missing—crews of aircraft lost over enemy territory.

The unusually high number of B-17s that had aborted was likely due to the attempt to conduct three missions in as many days, leaving insufficient time for adequate maintenance. The First Air Task Force had 27 Forts abort, reducing defensive firepower by more than 300 heavy machine guns.

Besides the losses of the 100th, the other two bomb groups of the 13th Combat Wing had suffered heavily as well. The 95th had launched 23 B-17s; three had aborted, five were listed as “missing in action” after the mission—four had fallen from the six of the group’s lower squadron. The 390th had set out with 22 aircraft; five aborted and eight were lost, the high squadron suffering five Forts lost out of eight.

Eighth Air Force gunners claimed 183 enemy fighters destroyed, and the 13th Combat Wing alone was credited with 105, but German records indicated only 26 fighters lost, most having been brought down by American fighters. The loses included seven Bf 109s, 10 Fw 190s, and nine twin-engine Zerstörer (destroyers)—five Me 110s and four Me 410s. As well as the German defenders performed, however, they failed to stop the bombers from attacking their targets.

The post-strike assessment indicated that Münster’s railway station received five direct hits from 500-pound bombs. The marshaling yards and a supply depot also sustained damage. The Germans’ own official police report stated that 60 soldiers and 301 civilians were killed, but other sources placed the number killed at 765. More than 25,000 were made homeless.

Bad weather grounded the Eighth Air Force for the next three days.

Four days after the Münster raid, the most ambitious raid during the week of 8-14 October was sent to destroy ball-bearing plants at Schweinfurt, deep in the Reich. Of some 291 B-17s launched on the mission, 60 were lost and another 145 were damaged.

After Schweinfurt, the next strike by the Eighth Air Force wouldn’t be conducted until October 20, when 170 B-17s were sent to Duren, Germany, about 35 west of Cologne—a considerably less-aggressive strike.

The Münster and Schweinfurt raids demonstrated the ability of the Luftwaffe to break through the tightly knit bomber boxes and inflict severe punishment, though it was a hazardous task for the German pilots.

The Luftwaffe had also demonstrated a capacity for mass concentration on one bomber formation at a time, launching rockets into the formations and repeatedly pressing home fighter attacks. Without long-range escort fighters to provide added protection, bomber loses were likely to remain high during deep-penetration missions.

From October 8 to 14, 1943, the Eighth Air Force hit industrial and military installations at Marienburg, Bremen, Münster, and Schweinfurt at the cost of 143 B-17s and 1,590 casualties, the six days referred to as “Black Week.”

The Münster raid was an ill-fated mission that helped to create the reputation of the 100th Bomb Group—the “Bloody Hundredth.”

Captain Ellis Scripture, lead navigator of the 95th Bomb Group, said of his fellow airmen: “One memory that stands ou t … was the calm way young men reacted to extreme danger, and especially during the vicious air battles with German fighters. This stands out as a lasting tribute to the men of the Eighth Air Force.”

The German 15-year-old, Otto Schuett, would later think of that day: “The events of 10 October 1943 often pass through my mind and, with those thoughts, pictures appear of the friends and neighbors who died on that day. A great sadness comes over me, and I also often wonder what kind of men the crews of those B-17s were that never returned home.”

Not a Focke Wulf Fw-190 fighter; it’s a ME109.