By Ed Miller

Santo Tòmas University, Manila, Philippines, about 9:00 p.m., February 3, 1945: Louis G. Hubele, a 45-year-old civilian internee of the Japanese, heard more than the usual amount of vehicle traffic on España Street.

Unsure of the reason, he headed to the Education Building, intending to talk to other internees about this development. They were aware of the American activity well north of Manila, yet they had no details. Perhaps the GIs were bearing down on the city. On the other hand, had the Japanese stopped the Americans?

Outside, Hubele saw the enemy soldiers taking up positions at the entrances to the compound and on the lower floors of the Education Building. Though weakened by hunger and unable to reach his own room in the building, he summoned the will to reach the third floor, where he found an open room and some other internees. The sound of large engines grew by the second.

As they hunkered below the windowsills, they began to hear unfamiliar voices—in English! The clamor grew. Shouts. Orders. “Get out of the windows! We will shoot at movement inside the building!” Figures in green uniforms fanned out in the twilight. The U.S. cavalry came to the rescue as if a Western film played out in real life. Three years in Japanese captivity were over for Hubele and many others. Hubele remarked, “We didn’t know any American troops were anywhere near Manila.”

The story of the liberation of about 4,000 Allied internees at Santo Tòmas University had nearly everything—“Flying Columns” of cavalry, desperate civilian internees, an enemy on the brink, a sense of desperate urgency, and even the press. How it took shape and succeeded in a matter of a few hours is worth study because today’s readers often relegate American operations in the Philippines (and the Pacific in general) to second place when measured against the enormous scope of operations in Europe. Yet GIs performed as admirably in the hot, muggy climate of the Philippines as they did in the bone-chilling cold of a European winter.

Planning for operations on Luzon, the political and economic heart of the Philippines, began in the summer of 1944. General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander, Southwest Pacific Area, successfully argued to President Franklin D. Roosevelt his case for invading the archipelago by the end of the year.

By October, MacArthur’s staff had completed an initial plan for taking Luzon and the capital of Manila, and he issued a preliminary operation order in mid-month. When the opportunity arose to make the initial landings on the island of Leyte that same month, he also advanced the target date for Luzon to December.

Several factors led to postponement of the operation. Bad weather caused significant logistical problems, planners did not identify early on the need for additional supporting air bases closer to Luzon than those on Leyte, and the Japanese proved to be an exceptionally a tenacious enemy. MacArthur delayed the invasion (“S-Day”) until January 9, 1945.

General Yamashita Tomoyuki, the 58-year-old commander of Japanese ground forces in the Philippines, had about 260,000 troops on Luzon, though the force was weak in artillery, armor, and logistics units. Yamashita had no intention of strongly defending Manila, a city of over 800,000, and the central plain against overwhelming American mobility. He intended to force the Americans to fight for the rugged mountains surrounding the plain.

Yamashita rightly considered the city indefensible, despite the fact that many of the newer buildings in the downtown area were built from heavily reinforced concrete to withstand earthquakes (and, as it turned out, American tank and artillery fire).

Disagreements between his subordinate army and navy element commanders impeded operations. He placed the defense of Manila under Lt. Gen. Yokoyama Shiuzo and ordered the city’s evacuation, except for a rear guard element. However, as army troops departed, several thousand sailors under Rear Adm. Iwabuchi Sanji moved into the city without orders from Yamashita and prepared to destroy it if necessary.

The Japanese built intricate defenses, screening Manila’s outskirts with mobile troops and placing some strong fixed positions north of the Pasig River inside the city. They devoted most of their effort to preparing complex defenses south of the river, including roadblocks, mines, and over 350 gun positions.

An American report said that the enemy “fought tenaciously and skillfully to the bitter end, using all available weapons and barriers, natural and artificial.” The 1st Cavalry Division’s G-2 (Intelligence), Lt. Col. Robert F. Goheen, concluded the day before the liberation of the internees that “the evidence is unimpeachable that in the streets and buildings of Manila and its suburbs that there has been an incessant construction of defensive works and positions of astonishing variety. It is reported that bridges are mined and electrified, tank obstacles are imbedded in the pavement, barricades are raised, charges are laid under important buildings.”

Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger, commander of the Sixth U.S. Army, disagreed with MacArthur on the potential for an enemy counterattack from the high ground on Luzon’s interior against American forces moving south on Manila.

MacArthur, no doubt determined to repay what he believed was a national debt to the Philippine people, told Krueger to disregard the threat and focus instead on driving fast south against Clark Field and Manila, which was about 120 miles from the Lingayen Gulf landing beaches.

In addition to its political and symbolic value, Manila’s port facilities were critical to sustaining operations both in the islands and during an invasion of Japan itself.

Only the U.S. military could undertake operations of such scale. Sixth Army staged from Leyte, New Guinea, the Solomons, Western New Britain, and New Caledonia, assembling units of all types scattered over thousands of square miles of island-dotted ocean. Two corps (I and XIV) would each put two infantry divisions and supporting units ashore in the Lingayen-Damortis-San Fernando area of Luzon, in the first wave.

As reinforcing units landed, the Americans would establish air, naval and ground bases, seize the central plain/Manila area, and establish control over the remainder of the 40,000-square-mile island.

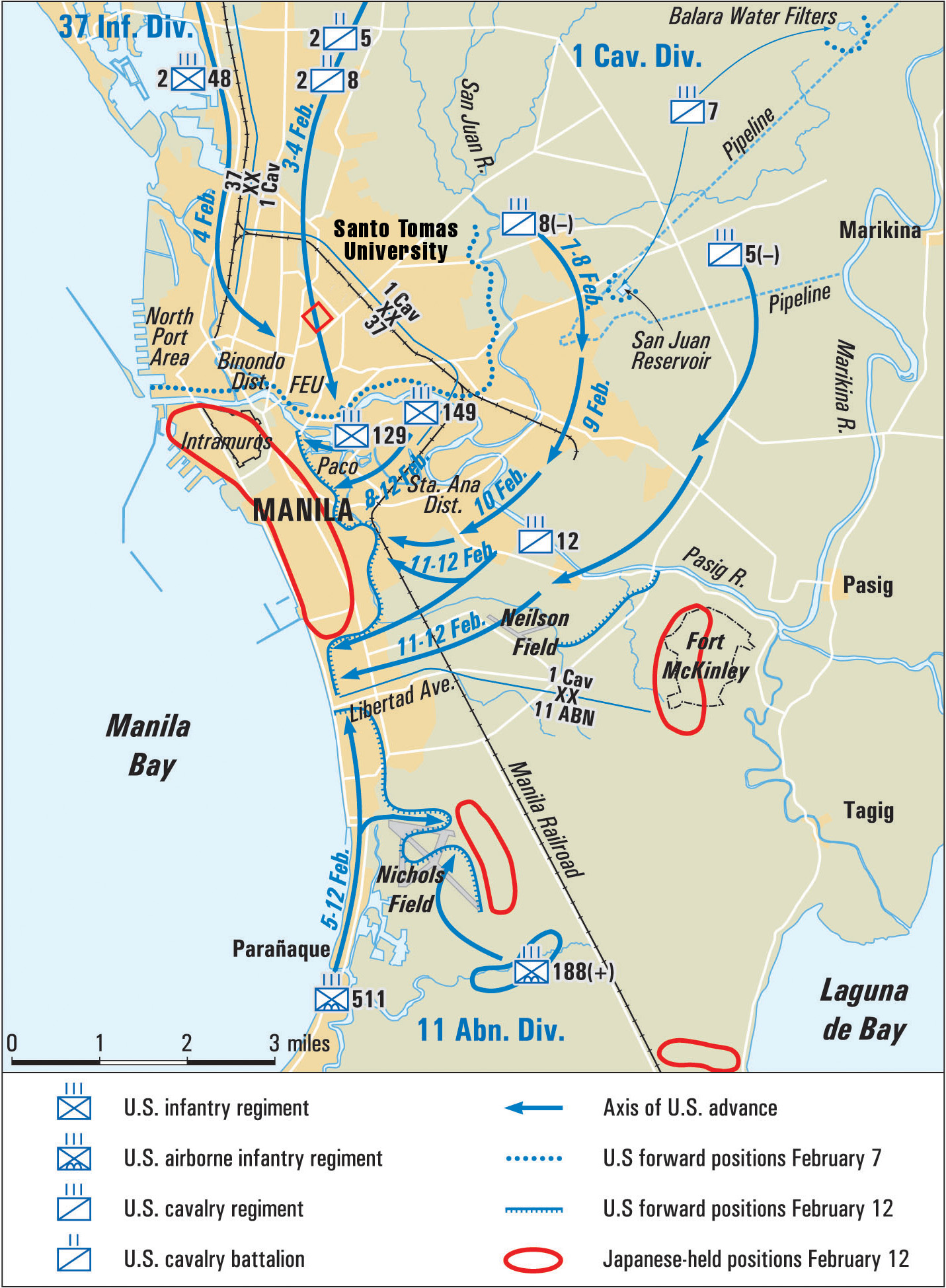

Yamashita’s decision to concentrate his defenses in Luzon’s high ground meant that the American landings went generally according to plan and schedule, with little opposition. MacArthur in late January released the 1st Cavalry (Maj. Gen. Verne D. Mudge) and the 32nd Infantry Divisions (Maj. Gen. W.H. Gill) to Krueger, who in turn ordered the XIV Corps (Maj. Gen. Oscar W. Griswold), to seize crossings of the Pampanga River, Clark Airfield, and Manila.

Urging his generals to move fast, MacArthur on the afternoon of January 30 met with Krueger, Griswold, and Mudge, whose division had been ashore only three days. “Go to Manila, go around the Nips, bounce off the Nips, but go to Manila,” he demanded. There, free the civilians interned at Santo Tòmas and capture the Malacañan Palace, the seat of government, before midnight on February 3—then hold until reinforced.

MacArthur was firm, though Krueger and Griswold remained concerned about the potential enemy threat from the high ground.

Soon after the meeting, Brig. Gen. William C. Chase, commander of the 1st Cavalry Brigade, received the mission of attacking 100 miles beyond the American lines, entering Manila, and liberating the internees. Mudge called a meeting of his senior commanders at 7:00 p.m. and announced that Chase would command two “Flying Columns” organized around Lt. Col. Haskett L. “Hack” Conner’s 2nd Squadron, 8th Cavalry Regiment (2/8), and Lt. Col. William H. Lobit’s column organized around the 2nd Squadron, 5th Cavalry Regiment (2/5).

Ashore only a few days, the cavalrymen had been able only to organize for combat, resupply, and refuel. A third element, a Provisional Reconnaissance Squadron (PRS), under Lt. Col. Tom Ross, controlled two tank companies and a reconnaissance troop.

Chase held a final commanders’ meeting at 9:00 a.m. on New Year’s Eve, January 31, 1945, and Mudge issued a final written field order later that night. The initial target was the Cabantuan–Santa Rosa area, where the Flying Columns would cross the Pampanga River early on February 1. Ross’ PRS would secure crossings over the Angat River and maintain contact with the adjacent 37th Infantry Division.

The cavalrymen entered the battle after continuous action in incessant bad weather on Leyte and without rest or receipt of replacements before the Luzon battle. Mudge nevertheless wanted the cavalrymen to strike “with paralyzing speed and vigor to clear route of advance for foot troops” who would follow the columns “aggressively.”

Each element carried six day’s supply of rations, fuel for 400 miles, and all the ammunition they could haul. Each soldier would carry two canteens, and obtain extra water locally for purification by attached engineers. No one walked—all troops rode in the vehicles or on the tanks.

Chase knew the terrain between the division’s assembly area north of Cabantuan and Manila, having served in the Philippines in the 1930s. Route 5 was the axis of the Flying Column operation, though Chase instructed Lobit (2/5) to first move east toward the high ground bordering the Luzon Plain. If this drew the enemy out of his defenses, Lobit would buy time for Conner’s 2/8 column to continue to Manila on its own.

Alternatively, should the enemy stop Conner, Lobit would assume the lead and Ross’ PRS would be prepared to support either Column.

Chase’s mobile command post, including a Marine Corps forward air controller with access to two air groups, began the attack following Lobit. He recalled that the columns were stripped down and traveled light, but “what we had a great deal of, however, was high spirit and morale and a grand desire to get into Manila first.”

The 1st Cavalry Brigade Combat Team consisted of the 2nd Squadron, 5th Cavalry (Lobit); Battery A, 82d Field Artillery Battalion; Company A, 44th Tank Battalion; 3rd Platoon, Troop A, 8th Engineer Squadron; Company B, 85th Chemical Mortar Battalion; 1st Platoon, Troop A, 1st Medical Squadron; 19th Portable Surgical Hospital; a platoon from Troop A, 16th Quartermaster Squadron; and Maintenance Support Detachment, 27th Ordnance Company.

Lt. Col. Thomas H. Ross’ Provisional Reconnaissance Squadron was comprised of the

44th Tank Battalion (minus Companies A and B) and the 302nd Recon Troop.

There was no artillery preparation before Chase gave the order to move at one minute after midnight on February 1, 1945. A brilliant moon helped combat engineers seize the northern approaches to the Pampanga River bridge near Cabanatuan.

At 6:30 a.m., as 1st Lt. William Leach and his men were approaching the south end of the span, they saw that the enemy had blown 20-foot gap in the floor, so the engineers spent an hour looking for a usable ford. Lobit’s troops were across by early afternoon, held up for a few hours by about 250 of the enemy fighting from of “well-entrenched positions.”

Most of Conner’s column (2/8) was across the river by mid-morning. Troop G, which met no resistance in a diversionary attack, was unable to get all of its vehicles across a poor ford and the commander ordered the elements that were not across to rejoin the main body of the 2/8 column. The elements remaining across the river would move to a pre-designated site and await the rest.

A Filipino guerilla reported that when this group, including the troop commander, reached the link-up point and found no other Americans, the commander evidently decided he was late and that the squadron had moved on. His group continued moving south along Route 5 for nearly 40 miles before an artillery liaison plane found them engaged with a Japanese force near the town of Baliuag. The pilot relayed Conner’s order to break contact and withdraw north until reinforced.

Lt. Col. Ross’ PRC was meanwhile across the Pampanga River south of Cabanatuan. The light tank company (D/44th) pushed south to Gapan and the Peñaranda River, where it hit enemy infantry defending the town; Ross was one of the casualties. The Japanese searched his body before it was recovered by the Americans, and took some of his papers. Ironically, the stray element of Troop G had earlier passed through the town with such speed that the enemy was unable to react to it until seconds before its last vehicle cleared. They were apparently ready for the PRS.

At about 4:00 p.m. on February 1, the now-reassembled Troop G, 8th Cavalry, attacked Gapan and helped the tankers stabilize the situation; GIs found several enemy dead after the fighting. Colonel Conner ordered the remainder of his column to continue Gapan. Captain Thomas Barrow recalled, the “marching, countermarching amid some confusion [was], in view of the very light enemy resistance … not so good. We of the Squadron were beginning to learn a little more about coordination of a fast-moving force, however.”

The next day Conner reinforced each of his cavalry troops with a platoon of Sherman tanks, and his squadron continued south toward Plaridel. Japanese infantry again delayed the column at a blown-out highway bridge across yet another river, the Angat.

Combat engineers told Conner that the bridge would take hours to repair. Troop G laid down fire to distract the enemy while Troop F located a ford passable for tracked vehicles. This still cost precious time because the tanks had to tow the wheeled vehicles across the Angat.

Since this column also came into contact with elements of the 37th Infantry Division, which was moving on Manila from the northwest, Chase permitted Conner to hold in place for refuel, maintenance and resupply amid a crowd of cheering Filipinos. The day’s gain was only 14 miles.

A map reconnaissance indicated a promising route for February 3, until a Filipino guerilla officer who knew the area told Conner that it would expose his column to strong enemy forces then withdrawing into Manila from the northeast. Aerial reconnaissance late in the afternoon confirmed that bridges on the route were intact but presumably well defended. Believing there was little alternative, Conner gave the order to move out at 9:00 p.m. on February 2.

Guerillas reported to the Troop G commander that the enemy was passing through Santa Maria, a town about midway between Manila and Baliuag. At about 2:00 a.m. on February 3, elements of the troop hit enemy outposts, and called for mortar and heavy machine-gun support. Troops E and F at daylight forced back the enemy.

The Santa Maria River crossings were by this time damaged, but a platoon leader reported a useable ford about 1,000 yards away. Yet, when the platoon crossed the river, it ran into an ambush and was pinned down. Troop F and its attached tank platoon went to assist and killed an estimated 30 defenders.

Moving next to the town of Muzon, 2/8 destroyed 15 trucks and killed two dozen enemy soldiers in a harsh firefight. Not long afterwards, the cavalrymen dismounted to clear more opposition and realized that the enemy was present in force. GIs dismounted, taking cover in drainage ditches along the road. Captain Barrow believed the enemy was about as surprised as the Americans. This firefight lasted about a half-hour.

Colonel Conner’s leading elements finally reached Novaliches late on the afternoon of February 3. Just five miles from the outskirts of Manila, fire from three directions at the bridge over the Tuliahan River hit the column. One group of cavalrymen found a mine “with enough explosive to demolish two bridges.” Lieutenant (j.g.) James P. Sutton, USNR, an explosive ordnance expert attached to the Sixth Army, disassembled the charge under fire. (He received the Army’s Distinguished Service Cross and, in 1949, was elected to represent Tennessee’s 6th Congressional District.)

Sutton was not the only person recognized for heroism at Novaliches. S/Sgt. John T. Lee and T/4 Samuel L. Hardin received Bronze Stars for disregarding their own safety to run inside a burning building to rescue injured Filipino civilians.

Barrow said, “From here on to the final objective at Santo Thomas [sic] the column’s movement resembled a Wild West movie. Off and on for the entire distance, some 12 to 15 miles, the Squadron received fire from the flanks of the road, which was vigorously returned from both tank guns and truck-mounted machine guns.”

Chase, initially moving behind Lobit’s column, recalled that Filipino men, women, and children lined the roads when they were sure the enemy was gone, yelling “’Mabuhay!” and trying to give the Americans food. Chase was particularly fond of papaya and bananas. In fact, he thought Lobit’s “entire column” was “eating its way toward Manila” under the cover of Marine aircraft. Chase spent the night of February 1-2 in a home recently used by Japanese General Yamashita, who was traveling in the opposite direction.

Lobit’s column reached the Angat River at Sabang, near the 2/8 crossing site, at midday on February 2. He learned that, while the bridge he wanted was damaged, nearby fords were passable if the tanks pulled the trucks across the river bottom.

This process took about six hours and the column continued to move east in heavy rain toward the high ground to determine if the Japanese would in fact attack the cavalry division. They were on a narrow, one-lane road lined with houses and could make only 5-10 mph in the growing darkness. Five riflemen rode on each tank and all those in the trucks were ready to return enemy fire.

“The night [2-3 February] suddenly became alive with all kinds of sound,” said Lobit. From a ridgeline paralleling the column, an unknown number of enemy opened fire. Lobit’s artillery commander, Major J.P. Henry, ordered his 105mm howitzers into position. When Lobit radioed for a report, Henry replied, “The guns are in position and I have 900 rounds ready to fire.” Adjusting by sound in the darkness, the forward observer needed only three rounds to put the howitzers on target.

Lobit knew at dawn on February 3 that guerillas were in control of the approaches to the route of march, and he ordered his column to move back to the southwest toward Santa Maria. Still hampered by the lack of bridges and useable fords, Lobit ordered the tanks to take yet another detour, while the wheeled vehicles moved at speeds of up to 25 mph on Route 64, then at speeds of up to 50 mph along the gravel surfaced Route 52, determined to catch up to the 2/8 column—and to General Chase, who was now moving with Hack Conner.

At a crossroad near Santa Maria, the absence of villagers told Chase that the enemy was close by. Halting temporarily to wait for some vehicles to pass, his brigade S-2, Major Lyman Bothwell, entered a store and returned with cigars and beer. Chase took a quick break.

Meanwhile, the commander of the 82nd Field Artillery Battalion, Lt. Col. Harry Lambert, was in a liaison plane overhead, and reported during the late morning of February 3, “Have seen all the way to Manila. Situation for us looks good.” Marine pilots then reported that the Santo Tòmas University compound was intact but there were many fires breaking out across the city.

The ground was relatively flat and open near the hamlet of Talipapa, just four miles northeast of the Manila city limits. Four enemy trucks carrying troops and supplies almost literally ran into 2/5. GIs waved the enemy to stop, and they amazingly complied, probably momentarily thinking they were linking up with a column of their own forces. Unfortunately for the now-vulnerable Japanese, as each American vehicle passed, GIs “unloaded” their weapons and left all four trucks burning, killing at least 25 of the enemy.

Conner’s 2/8 column entered metropolitan Manila about 6:30 p.m. on February 3, tanks and troops firing at any position they suspected an enemy soldier might occupy. The situation remained fluid and uncertain. Despite the news from the reconnaissance pilots, Chase could not afford complacency and told Conner to move rapidly. Would the enemy now try to destroy the internment camp and the civilians within it?

Troop F and attached tanks, accompanied by Lt. Col. Conner, disregarded security and sped deep into the city. Cavalrymen seized the Malacañan Palace on the north bank of the Pasig River and headed toward Santo Tòmas.

Two platoons of Troop G reconnoitered the river itself and ran into very heavy enemy automatic-weapons fire. Drivers frantically tried to turn around in what was a killing zone at the Far Eastern University campus.

After three officers were wounded, Sergeant John Gallagher organized a defense against repeated enemy attacks. An engineer lieutenant, George N. Renshaw, led his platoon out of an ambush. Two other engineers, S/Sgt. Adolph E. Bart, and T/5 Lloyd F. Madaus, manned a bazooka and destroyed two trucks carrying Japanese reinforcements. Guerillas helped them organize and bypass the ambush and they reached Santo Tòmas by midnight, where the remainder of Conner’s unit was in the process of securing.

Chase reached the city limits before 8:00 p.m., followed by 2/5. He recalled, “Fires and explosions breaking out on all sides, much sniping and firing at every street corner, and even a Japanese counterattack on our column.”

Three enemy trucks dashed out of an alley beside his command vehicle and he shot at them with his .45-caliber pistol. GI rifle and machine-gun fire caused the truck to burst into flames just yards away, the flames illuminating a landscape of noise and smoke as Chase and his command group moved on.

Nearby, on Quezon Boulevard, the headquarters staff helped to silence a roadblock. Chase was out of his vehicle when a bright flash went off near him. Before his aide and orderly could fire at the apparent source of the flash, an American voice yelled at them not to shoot—it was a cameraman’s flash bulb. War correspondents had descended on Chase’s force at the start of the operation and were still with the cavalry. Each of them wanted to be the first reporter into Manila. After clearing the Calle España for use as a landing strip, the Army established regular runs for exposed film and news copy.

It was a scene worthy of a movie when the tanks led the remaining platoon of Troop G, Troop H, and the remainder of the 2/8 column to Santo Tòmas University, where a Sherman tank named “Battlin’ Basic” crashed through the gate to the cheers of the 3,600 internees. Conner, however, was wounded and his executive officer directed the clearing of the University grounds.

As the soldiers stabilized the situation and cleared the buildings of the enemy, Chase’s brigade S-4 (logistics officer) reported there was no food to give the internees for breakfast the next morning. The resourceful staff officer somehow located the nearby offices of the Catholic Bishop of Manila, who helped supply rice, fish, and vegetables. The S-4 also sent Chase a bottle of scotch, which he combined with a hard-boiled duck egg for breakfast the next morning. An “unusual, but an invigorating, way to start any day,” reported Chase years later.

Major Bothwell, Chase’s S-2, brought word about 10:00 p.m. that the enemy camp commander, Lt. Col. Toshio Hayashi, with about 275 of the civilian internees and about 70 of his own men, were barricaded in the Education Building. These were the same enemy that Louis Hubele had seen a few minutes before.

Hayashi wanted to take his men to Japanese lines south of the Pasig River. Little wonder, because guerillas had already reported that the area was heavily fortified and under the firm control of Japanese Navy forces.

Colonel Charles E. Brady, Chase’s Chief of Staff, during daylight on February 4, tried without success to persuade Hayashi to surrender. He replied that his men would kill the civilians if the Americans did not permit his force to remain armed and to cross the Pasig.

With civilian lives at stake, Chase had no choice but to agree to the terms. Early on February 5, Troop G, 8th Cavalry escorted the enemy to the river. Despite some criticism, Chase maintained he did the right thing and noted that MacArthur approved the decision. GIs did not clear the last resistance in the university complex until about the time this group left for enemy lines.

Texas businessman Louis Hubele recalled that the Japanese provided only very basic rations during the war, and the internees who had outside contacts and the resources to obtain money, helped set up trade with local food vendors. Internees responsible for maintaining the camp, who worked or needed medical care, could go outside from time to time, but most were confined to the university complex.

As time went on and the war turned against them, the Japanese became more difficult. Cases of beriberi and starvation grew after they ended access to the outside vendors in early 1944. By the end of the year, Hubele was down to a can of Spam, and he and his wife shared their last corned beef for Christmas; there was not much left but rice. (Hubele and his wife returned to Texas in 1946.)

Even as the GIs secured the university compound, some of the cavalrymen reconnoitered the Pasig River bridges and reinforced their small perimeter to enable other units to take charge of the internees. It did not take long for reports to reach Chase that “considerable parts of the city have been wrecked or burned.”

The release of the civilians from years of Japanese captivity marked only the beginning of the battle of Manila, which would drag out for a month and result in the destruction of thousands of buildings and 100,000 Filipino lives.

This attack also marked the end of General Chase’s command of the 1st Cavalry Brigade; the 49-year-old took command of the 38th Infantry Division, also in the Philippines, on February 7. His lightly armed “Flying Columns” had, in about 72 hours, stormed over 100 miles, killed about 1,200 Japanese (they took only two prisoners), and liberated about 3,600 Allied prisoners and internees held in Manila.

The geography of the Southwest Pacific Theater was clearly not well suited to comparatively large-scale mobile operations, and this was the only example in the Pacific Theater of such a drive deep behind enemy lines. American doctrine for mobile operations proved adaptable to the circumstances of the Pacific if the terrain permitted them.

Leaders, however, lacked the opportunity to practice the doctrine during the remainder of the division’s operations during the war. Chase returned to the 38th Division as its commanding general at the end of the war and took it to Japan as part of the occupying force. It remained overseas for years, eventually deploying to Korea to fight a new enemy. But that is another story.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments