By Steve Ossad

Hitler called it an “abscess.” British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, the chief sponsor and loudest cheerleader for the endeavor, grudgingly proclaimed it “a disaster.” Lt. Gen. Mark Clark, commander of the U.S. Fifth Army, described it as a “strip of hell.” American GIs, their British brothers-in-arms, and their German adversaries had more profane and gruesome descriptions, most of which would never pass a censor or editor’s review.

The bloody four-month agony of Anzio was one of the most difficult campaigns ever fought by an Anglo-American army. In spite of its ultimately disappointing results, it was also a heroic stage upon which the grim determination, bravery, and sacrifice of Allied soldiers was displayed. By Mark Clark’s calculation, more than one in five Medals of Honor awarded to ground soldiers of the U.S. Army during World War II went to men who fought at Anzio.

Even before the end of the battle, however, arguments about responsibility for its disappointing outcome had begun, and they have continued ever since. While the terms and tenor of the debate have varied over the years, there is one constant element in the discussion: whether or not the principle responsibility for the failure to outflank the enemy belongs to American VI Corps commander Maj. Gen. John P. Lucas or elsewhere. Should Lucas have moved aggressively immediately after the successful landing to seize the Alban Hills and cut the German lines of communication and supply, or was he right to consolidate the beachhead, build up his forces, and protect the port that was crucial to his survival? As historian Martin Blumenson framed the question, had Lucas been “prudent” or simply “paralyzed.”

John Lucas first gained notoriety early in the 20th century during a fabled episode that still stirs America’s imagination and influenced its policies and leaders for decades. Late on the evening of March 8, 1916, 2nd Lt. Lucas, then machine-gun troop commander of the 13th Cavalry Regiment, got off the “drunkard special,” the train connecting his duty station at Columbus, New Mexico, with free-wheeling El Paso, Texas, where he had spent the previous week playing in the inter-regimental polo matches. A hunch had moved him to return home after the last match rather than the next morning. Now, bone tired, he was ready to collapse in his bunk.

One more chore remained. His roommate, fellow West Pointer 2nd Lt. Clarence C. Benson, had gone on maneuvers and had swiped most of the revolver ammunition. Lucas wanted to make sure his .38 was loaded—a second hunch or perhaps a premonition of danger. He finally drifted off to sleep well

past midnight. At 4:30 am, he was awakened by the sound of a galloping rider passing his cottage. He looked out the window and instantly realized that Pancho Villa’s outlaws had surrounded his house and were moving on the town.

He grabbed his pistol and took a position in the middle of the room, where he could command the door and window. He fully expected to die but was determined to “get a few of them before they got me.” A sentry posted nearby—who paid for his bravery with his life—saved Lucas by shooting a bandit about to enter the bungalow. The outlaws scattered. Hurrying outside, Lucas joined them, relying on the darkness to hide his identity. After slipping away and rallying his men, Lucas helped secure their guns, and his troop unleashed a terrific barrage, helping to rout the invaders out of town. Lucas emerged from the fracas a hero, but in a stroke of bad luck his commander’s recommendation for a Distinguished Service Cross was mishandled and he received no official recognition.

John Porter Lucas was born on January 14, 1890, in rural West Virginia. After graduation from West Point in 1911, he was commissioned into the cavalry. After several years of duty in the Philippines, he served in the Mexican Punitive Expedition to chase down and eliminate his erstwhile nemesis, Pancho Villa. When America entered the Great War, he took command of the signals battalion of the 33rd Division and in June 1918 was wounded during the Amiens campaign. Sent back to the Uunited Staes for convalescence, he was transferred to the Field Artillery, and for the next 20 years his career followed the normal pattern of field and staff assignments, stints as student and instructor at the Army’s schools, and glacially slow promotion.

As war preparations and the expansion of the Army gained momentum, he was promoted to brigadier general in 1940 and several years later took command of the 3rd Infantry Division. As a result of the vigorous training programs he initiated during this period, Lucas gained a reputation as one of the few senior American officers with expertise in amphibious operations. He had already attracted the attention of Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall, who described him as possessing “military stature, prestige, and experience.”

Dispatched in 1943 to North Africa as a headquarters observer, Lucas returned to the United States to take over III Corps but was soon ordered back to the Mediterranean, this time as lieutenant general and theater commander Dwight Eisenhower’s deputy or, in his words, Ike’s “personal representative with the combat troops” in Sicily. After that campaign and a brief assignment leading II Corps, he relieved Maj. Gen. Ernest J. Dawley and took command of VI Corps on September 20, 1943, just 10 days after the Allied invasion of the Italian mainland at Salerno.

Affectionately called “Sugar Daddy,” “Foxy Grandpa,” or “Corncob Charlie,” Lucas performed well in spite of great difficulties, solidifying his reputation as a steady, unflappable, and experienced combat leader. His boss, Mark Clark, noting Lucas’s effective employment of artillery and innovative use of pack mules for supply in the impassable terrain, told him in admiration, “You know how to fight in the mountains.” Four months of grueling mountain warfare, however, had exacted a high personal cost. Lucas was exhausted, dispirited, and discouraged, and he emerged from the battle “looking far older than his 54 years.” Had his combat career ended at this point, his place among the small group of universally respected wartime American corps commanders would have been assured. In fact, he fully expected to be relieved and dispatched home to a training command, a prospect he quietly welcomed. Events, however, would soon overtake his urgent and obvious need for a long rest.

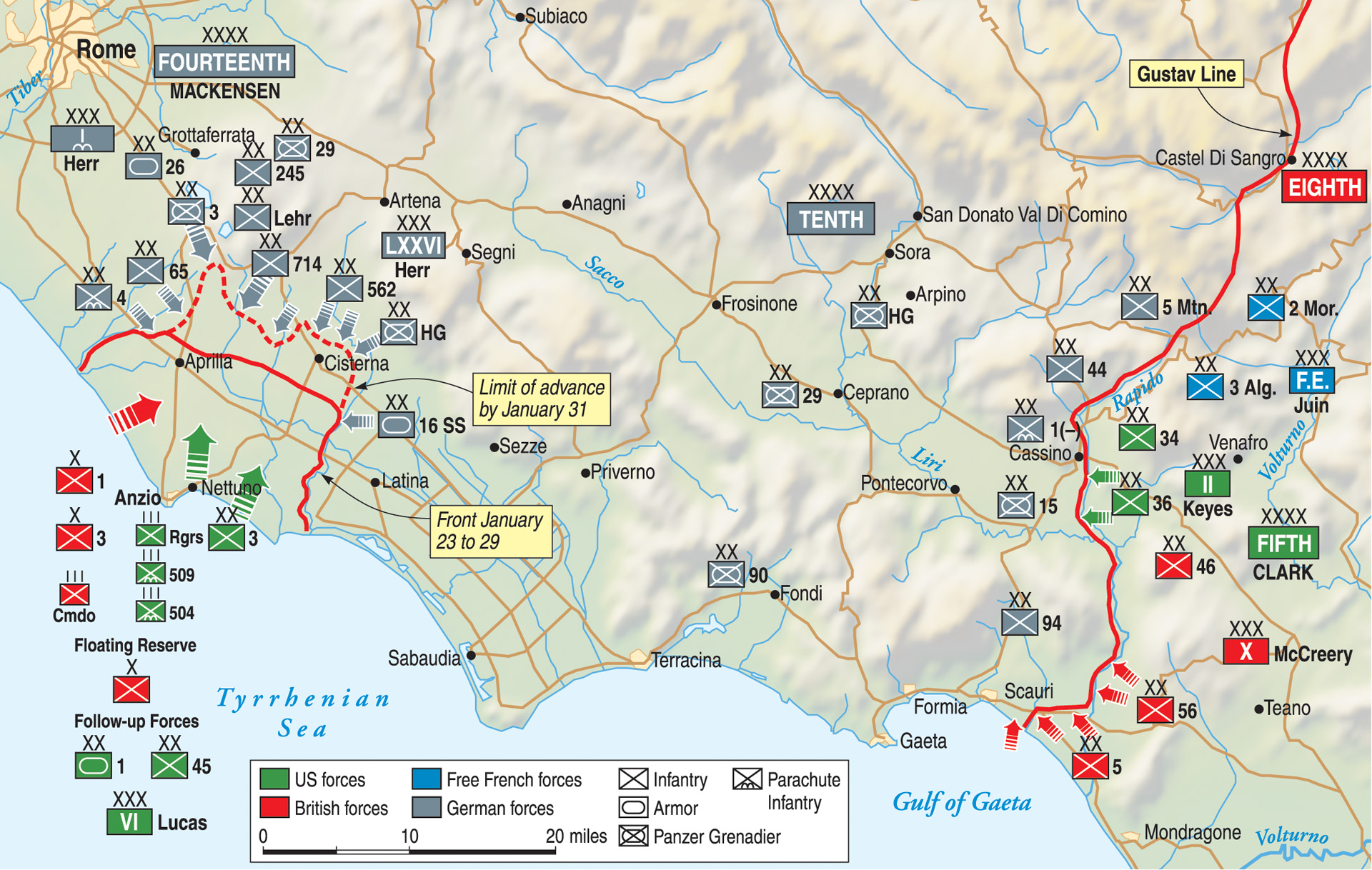

By late 1943, the Italian campaign had settled into a bloody stalemate with the Allies unable to break through the German Gustav Line north of Naples. Among the solutions considered by the senior theater commanders, Eisenhower and 15th Army Group commander Sir Harold R.L.G. Alexander, was an amphibious operation to outflank the strong enemy defenses. The planners soon focused their attention on Anzio, a small fishing and resort town on the Tyrrhenian Sea just 32 miles south of Rome.

A number of characteristics made it an attractive choice. Most important was the availability of a functioning port, first constructed by Anzio’s most famous native son, the first century ad Emperor Nero and rebuilt at the end of the 17th century. The Allied experts were certain the circular facility would be able to sustain a major amphibious force operating behind enemy lines. Furthermore, the surrounding terrain was suitable for a large-scale landing and subsequent expansion of the beachhead. Finally, Anzio was well within range of Allied ground support aircraft based near Naples.

On November 8, 1943, Eisenhower ordered Alexander and his American subordinate, Mark Clark, commanding the U.S. Fifth Army, to begin active planning for the landing code named Operation Shingle and tentatively scheduled for December 20, 1943. For various logistical reasons, that plan was soon scrubbed but was later resurrected after a command reorganization of the Mediterranean Theater. That change shifted the decision-making initiative to the British, whose enthusiasm and strategic interest in operations in Italy, including Operation Shingle, far exceeded that of their American allies. The British—inspired by Churchill—felt that the indirect approach through the soft underbelly of Nazi Germany and a crucial political-military objective—Rome—could best and most quickly be achieved via an amphibious landing at Anzio. That maneuver would reduce the pressure on the main Fifth Army front stalled at the fortified Gustav Line and allow a decisive breakthrough right to the gates of the Eternal City.

A victory would also reassert the importance of the British, whose global influence was rapidly waning under the steady buildup of American and Soviet power. Churchill wielded his considerable influence to secure the necessary support, especially scarce landing craft, to make a landing in late January possible. He smothered any opposition to the plan by force of personality and channeled his energy to motivate his senior commanders, especially Alexander and Clark, whose reservations soon evaporated in the face of the prime minister’s eloquent fervor.

During the course of the stop-and-go planning effort, two distinct approaches to the ultimate objective of the landing had emerged. The British view was that the Anzio operation should be the main strategic focus. Alexander believed that seizing the Alban Hills was essential to cutting supply arteries to the Gustav Line and forcing a German withdrawal. While he never issued an unequivocal order that specified his wishes, his instructions to Fifth Army on January 2, 1944, came close. Clark was instructed to “carry out an assault landing … with the object of cutting the enemy lines of communication and threatening the rear of the German XIV Corps.” On January 12, 1944, Alexander repeated that the object was to “cut the enemy’s main communications in the Colli Laziali [Alban Hills] area.”

The American view was that the main objective should be forcing the Gustav Line, anchored on the town of Cassino. The goal of the Anzio landing, therefore, was to draw off enemy forces from the main front, enhancing the possibility of a breakthrough and subsequent linkup. Political pressure, especially from the British, smothered any attempt to reconcile the two views. This inherent conflict of purpose just beneath the surface would help stoke the recriminations and decades of debate that followed the battle.

All that remained to put the plan into effect was the selection of the landing forces and commander. In spite of reservations about his physical stamina and aggressiveness, Clark quickly settled on Lucas and his American VI Corps, built around the U.S. 3rd (Maj. Gen. Lucian K. Truscott) and British 1st (Maj. Gen. W.R.C. Penney) Infantry Divisions. Alexander expressed his agreement, describing Lucas as “the best American corps commander” and the most experienced in amphibious operations, a man in whom he had “every confidence.”

The endorsement was disingenuous. Alexander viewed Lucas as he did most Americans, as a lightweight, and his British colleagues, most of whom were uncomfortable with Lucas’s style, shared his opinion. British visitors to Lucas’s headquarters described it as a “debating society” that lacked firm direction, confidence, and clarity of purpose. What his American admirers regarded as a prudent and deliberate nature, his English colleagues viewed as “pathological slowness.” One young officer thought that they were “commanded by a dear old pussy-cat.” Most troubling of all, however, was the lack of Maj. Gen. Penney’s confidence.

While Clark’s choice of Lucas was reasonable on its face and not controversial, it was certainly not inspiring. Stolid, methodical, cautious, and careful, Lucas was no one’s idea of the aggressive, decisive commander suited to a desperate venture and likely to be confronted with many dangerous decisions along the way. Small in stature, slow of gait, and looking very much like a village librarian or accountant, he was already visibly old at 54. Just eight days before the landing, he marked his birthday, writing in his diary, “I am afraid I feel every year of it,” and a British soldier noted that he acted as if he were “10 years older than Father Christmas.”

From the start, Lucas was openly skeptical of the Anzio plan and believed he lacked the men and ships to conduct a successful landing, hold the beachhead, and mount a serious threat to the German rear. Technically, the mission was especially formidable. As a joint American-British undertaking, the special logistical problems of an amphibious operation were even more complicated than usual. He was especially put off by the bravura and overconfidence of the British, particularly Churchill and Alexander. The specter of the 1915 disaster at the Dardanelles, of which the prime minister had been the chief proponent, haunted Lucas, as the general’s diary makes plain: “The whole affair has a strong odor of Gallipoli and apparently the same amateur was still on the coach’s bench.”

Further, there had not been enough time to plan and prepare, as a disastrous rehearsal on January 19, 1944, made plain. Lucas’s entreaties for more time were summarily rebuffed, and he felt that his superiors knew more than they were revealing, writing in his diary, “Apparently everyone was in on the secret of the German intentions except me…. I wish the higher levels [of command] were not so overoptimistic.” Lucas’s intuition was vindicated with the much later revelation of the role Ultra intelligence played in the overconfidence of the Allied high command.

In spite of his reservations, apprehensions, and fears, however, Lucas was a disciplined professional and prepared himself for the task with grim resolve. The description of a famous dinner just before the landings illustrates his fatalism in the face of the general consensus of what lay ahead. George Patton, a friend and admirer of Lucas, warned him that he was being handed a suicidal mission and was almost certain to face disaster and even death. Lucas replied in his folksy manner, “I’m just a poor working-class girl trying to get ahead.” What he meant, of course, was clear to the attendees; he was a professional soldier and would carry out his orders no matter how misguided or impossible they might be.

Those orders were, in fact, deceptively simple: first, establish and protect a beachhead and then “advance on” the hills. The choice of words of the second part of the mission was intentionally vague. What does “advance on” actually mean? Does it mean, “advance toward” or “advance all the way to”—also implying the capture of the heights? The selection of words was described at the time as calculated and the result of much analysis. Clark justified it by the desire to offer Lucas a measure of flexibility in light of uncertainty about the scale and intensity of the German reaction.

A confidential discussion on January 12, 1944, between Lucas and Clark’s operations officer, Brig. Gen. Donald W. Brann, suggested that most of the Fifth Army staff believed VI Corps would have its hands full just establishing and protecting the beachhead. Although Brann’s briefing included advice from Clark that Lucas should not “stick his neck out,” the tactical decisions were left to VI Corps. In the most telling signal of all, during his visit to the beachhead on D-Day, Clark reminded Lucas again that his own aggressiveness at Salerno had nearly led to disaster.

At 0200 hours on January 22, 1944, VI Corps landed on the beaches of Anzio and Nettuno. It was, arguably, the most stunningly successful amphibious landing during World War II. Even the skeptical Lucas thought so. Achieving complete tactical surprise and virtually unopposed, VI Corps landed almost 50,000 troops, 5,200 vehicles, and most of its heavy weapons with the loss of less than 150 men killed, wounded, or missing. Two German battalions were quickly destroyed, and for 48 hours there were virtually no opposing enemy forces confronting the beachhead. During that time, Lucas achieved all his initial objectives, establishing a beachhead that was seven miles deep.

More than satisfied with the results and feeling as if he had won a great victory against all the odds, Lucas dug in and waited for more men, tanks, heavy weapons, and supplies to strengthen his hold on the beachhead and port. He limited his offensive operations to small-scale patrols and reconnaissance and made no significant advance toward the Alban Hills. During one ferocious German bombing raid on the port, Lucas displayed great personal courage for which he was awarded the Silver Star. In spite of the anticipated difficulties, Lucas had presided over a tactical triumph, and Clark and Alexander seemed to concur with his decisions.

The Germans, however, had not been idle, and the initiative and mood at headquarters, soon shifted toward them. Their buildup of forces opposite the beachhead exceeded expectations, and Lucas’s belated attempts at the end of January to move out from the beachhead met bloody failure opposite the American lines at Cisterna and at the other end of the landing beach where the British desperately and futilely tried to hold a small group of buildings quickly dubbed “the factory.”

As the stalemate continued to deepen with mounting losses, the erosion of confidence in Lucas grew. He rarely left his command post, and a Maginot Line mentality soon developed among the senior staff. At one conference, Lucas seemed confused and forgot the name of the crucial hills dominating the terrain. In a conference with newsmen he openly praised the German fighting spirit, seemingly oblivious of the impact such a statement might have on his men’s morale. Clearly a change was required.

The original plan had called for Clark to turn over Fifth Army to Lucas after Rome had been taken so the former could step up to Army Group command, but that was now impossible. The Allied high command, however, was reluctant to relieve Lucas right in the middle of a desperate fight. This was not the only time before or after that such a calculation delayed a much-needed change of command. After the disastrous Ranger-led attack on Cisterna at the end of January and the German counterattack, however, the pressure mounted. Lucas had to go. On February 23, 1944, as General Eberhard von Mackensen’s Fourteenth Army counterattack lost momentum, Maj. Gen. Truscott, the aggressive commander of the 3rd Infantry Division, took over VI Corps at the open insistence of Alexander.

Months of hard fighting followed until the Allies finally broke through the Gustav Line and marched into Rome on June 5, 1944. Even that victory was scant reward for all the suffering. The Normandy landings completely overshadowed the event, robbing Clark of glory and Churchill of his strategic and political victory. The cost of Anzio had been terrible; Allied losses were estimated at 7,000 killed in action, 36,000 wounded and missing, and another 44,000 noncombat casualties. Field Marshall Albert Kesselring estimated the Germans had lost 5,000 killed and 34,000 wounded and missing.

Lucas was promoted to deputy commander of Fifth Army and then quietly sent home, where he performed well in a series of training commands. His career was not officially marked with a failure, and his superiors, especially Clark, tried to spare his feelings and had only positive comments about his performance. The judgment of history, however, has not been so generous, and opinions have varied while the level of intensity surrounding the debate has not. Lucas died an exhausted and disappointed man in 1949 at the age of 59. Until the end of his life he believed that he had been given an impossible task and then abandoned—betrayed may not be too strong a description—by his superiors. His diary is full of self-justification and offers a bitter commentary on the battle and his perception of the perfidy of those who ordered him to do the impossible.

In the years since, two points of view have emerged. The aggressive school of thought posits that Lucas should have gone for the Alban Hills and Rome, if not immediately, certainly within the first few days of the landing. Even the Germans were surprised by his lack of aggressiveness. At the very least, he should have mounted a credible threat by taking several objectives beyond the beachhead. The prudent analysis is that the mission was flawed from the beginning, taking and holding the hills were beyond the capabilities of VI Corps, and Lucas did what was necessary to preserve the beachhead. Regardless of the answers to the lingering questions, there are always lessons in failure. What were they?

First, the choice of a field commander for a difficult mission should never be based on expedience, political acceptability, or the path of least resistance. It must be based on fitness for command, a thorough understanding of the mission and its requirements, and a belief in its chances for success. Mark Clark should have realized that Lucas was exhausted and both physically and mentally unfit for the rigors of an amphibious landing behind enemy lines. If he did not, then he was either negligent or willfully ignored the potential consequences of his choice. Further, Lucas had been frank in his criticism of the concept of the operation, its timetable, allocation of resources, and its chances for success. He did everything short of publicly predicting a disaster and was clearly saying (in so many words) that he should be reassigned.

Second, while Lucas was a poor choice for command, the failure of the operation cannot be laid at his feet. No one could have accomplished the mission. Why? For one thing, it is still not clear what the mission was. At the level of operational objectives, there was a fundamental disconnect among the goals of the British, the Americans, and the military realities in the field. Each Ally had a different and essentially contradictory view of the operation and its purpose. The British hoped to force the collapse of the Gustav Line by cutting the lines of communication at the hills. The landing was, therefore, the main effort. The Americans wanted to divert the Germans from their assault on the Gustav Line, draw off forces, and ease the way for the drive across the Rapido River and beyond, which Clark regarded as the main effort. The last-minute cancellation of a scheduled paratroop drop at the Alban Hills must have seemed to Lucas even more evidence that the high command did not view the hills as an objective for which excessive risks should be taken.

Third, regardless of the objective, the landing was doomed from the start. The effort was far too weak to mount a decisive blow—or even a credible threat—against the German lines of communication, nor was it strong enough to ease the way for the drive against Cassino. As Lucas himself noted, the landing of two divisions was not likely to send the Germans running in a panic, particularly since Clark had made no progress in denting the Gustav Line, supposedly a necessary precondition for the landing.

Even a cursory look at a map makes it apparent that the sheer mass of the objective would have required many times the size of the force that was committed. The compromise, really the failure to agree on a single objective, resulted in two widely separated efforts, each incapable of mutual support and neither strong enough to do its job. Compounding this basic confusion about the main objective of the landing were the respective attitudes of the Allies. The British were overconfident and overoptimistic, cheered on by Churchill. The Americans were unenthusiastic and skeptical. The irony is that the Gustav Line collapsed only after the frontal assault that Anzio was supposed to avoid. By that time, tens of thousands of soldiers had paid the price.

Fourth, the failure of 15th Army Group and Fifth Army to reach agreement on the campaign objective is bad enough, but Clark’s ambiguous orders to Lucas—“advance on” the Alban Hills—were inexcusable. While supposedly designed to allow freedom of maneuver, the unofficial personal briefing delivered by Brig. Gen. Brann at the start of the campaign left little doubt that Lucas was not expected to act aggressively. When a bloody stalemate ensued, Lucas was caught between Alexander’s frustration and Clark’s indecision and eventually became the victim of his superiors’ conflicting expectations and ambitions.

A fair assessment would have to conclude that that the Allies could not have taken and held the Alban Hills. They had neither the resources nor the unity of command necessary for such an ambitious goal. Had Lucas moved aggressively within the first few days, he might have taken several of the objectives along the way, such as Cisterna and Albano, heightening the threat to the German rear. That might reasonably be considered the least common denominator in the divergent British and American concepts of the operation. Whether even that achievement would have been decisive or prevented the bloodbath that resulted is far from clear.

Where, then, does the ultimate responsibility lie for the failure at Anzio? As in the earlier case of General Lloyd Fredendall during the North African campaign, the answer must be sought at a level higher than the field commander. The men responsible for the Mediterranean Theater—Clark, and especially Alexander, bear the major responsibility. They picked the wrong man for the job, gave him essentially impossible orders, and refused to take responsibility when the inevitable disaster materialized. Perhaps worst of all, they allowed an honorable soldier to bear the shame of their failure.

In the final analysis, the operation should never have been mounted. The high command should have directed its energies to a more creative plan for breaching the Gustav Line rather than the sacrifice it precipitated. Of course, that is easy to conclude in hindsight, but the fact remains that Anzio was a mistake, paid for in blood, and blamed on an honorable man.

As distinct from the relief of Fredendall after Kasserine, however, the issue was not the competence of the man selected. At Anzio, Alexander and Clark—and their political masters who ratified their decisions—selected a competent but exhausted soldier and hurled him into a grueling and bitter fight under the worst possible circumstances. It is hard in retrospect to understand how they failed to recognize Lucas’s diminished condition. The usual explanation—no one noticed he looked old, exhausted, and spent because he always looked that way—is not persuasive. By the time they could no longer ignore the effects of their mistake and it was impossible to avoid the necessity of a change of command, the battle had reached a critical moment, and the immediate relief of Lucas would have raised serious morale issues. A poor decision led to indecision and even more suffering.

Had Lucas been dispatched to America after the Salerno operation, he would have been regarded as a major World War II hero. Instead, he became deeply enmeshed in one of the bloodiest battles of the war and in a bitter historical debate. Still, there is something essentially sympathetic about Lucas, and his fate is heavy with irony. As a professional soldier he had no choice but to carry out an order he regarded as impossible, and he was fully prepared to die in the attempt.

The only other option would have been to decline the assignment and ask to be relieved, thus ending a distinguished career under a cloud. John Lucas, who had faced Pancho Villa alone, barefoot, and in the dark, was not prepared to do that.

Author Steve Ossad’s biography of General Omar Bradley will be published by the University of Missouri Press. He resides in New York City.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments