By Duane Schultz

First Lieutenant Gilbert B. Hadley—he liked to be called “Gib”—was buried back home in Kansas in 1997, some 54 years after he was killed in action on August 1, 1943. “He looked like Clark Gable,” a Kansas City newspaper wrote about Gib when he was young. He “could talk his way into or out of virtually anything and loved to wear his cowboy boots and pearl-handled revolvers into battle.” He was a handsome, rowdy, flamboyant guy, liked by everybody who met him, particularly his own flight crew.

Like many young men in those hard times before World War II, Hadley joined the Army for the pay. Meager as it was, it was better than no job at all. He scored high enough on the army’s intelligence test to be selected for flight training, and he loved it.

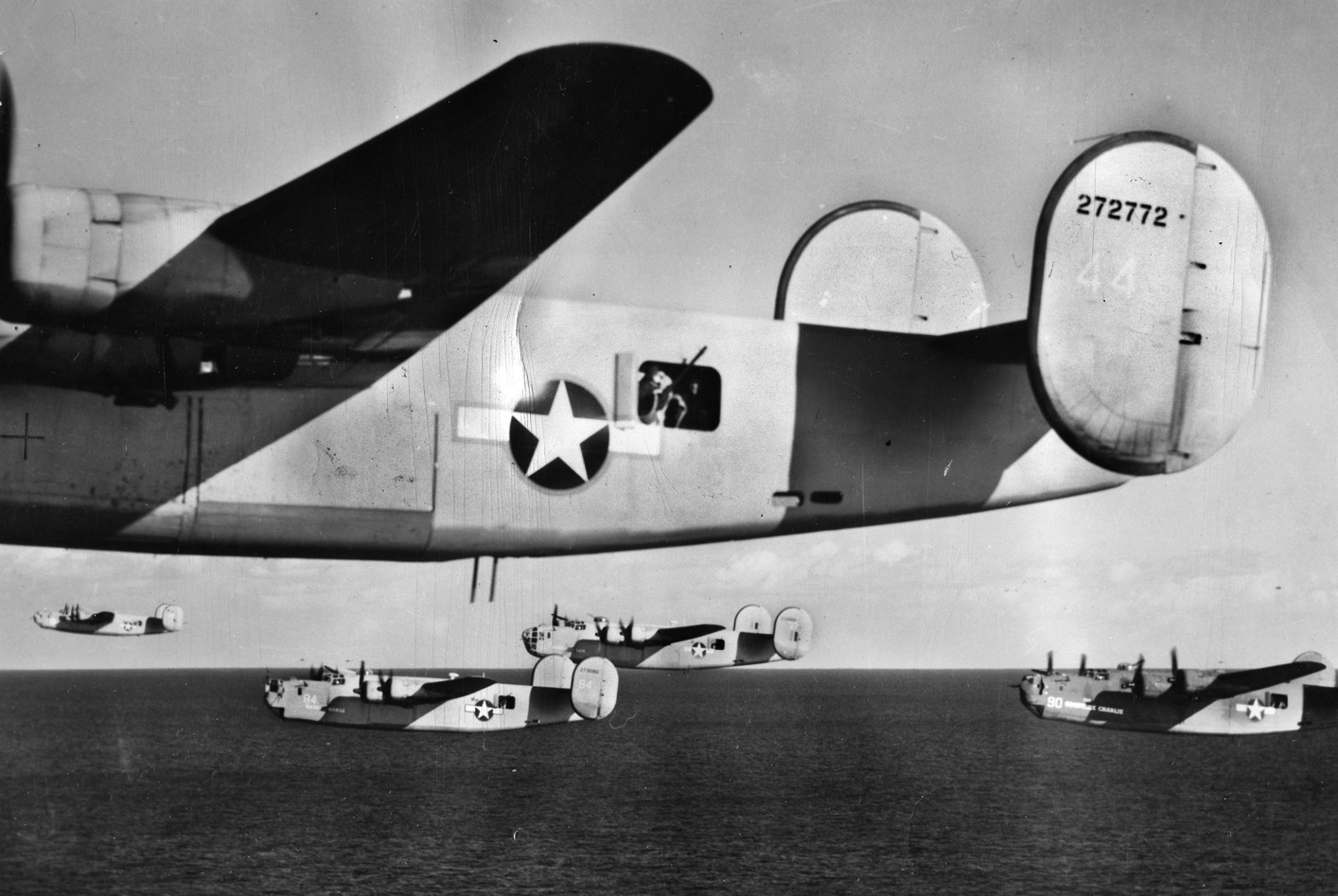

Gib’s early training took place not far from where he grew up, and he took great delight in buzzing the houses of his parents and friends, flying only a few feet over their rooftops. When he got assigned to the huge four-engine Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers during the war, he flew them the same way, scaring everyone but himself. When he got his own B-24, he named it Hadley’s Harem because he liked to think he had a way with the ladies. He wanted to paint nudes on the plane below the name, but the chaplain objected.

Gib Hadley was 22 when he died piloting his damaged B-24 and its crew 1,200 miles with two engines out back to Benghazi, Libya, in North Africa following a disastrous mission to bomb the oil refineries at Ploesti in Romania. Hadley’s Harem was one of 177 B-24 Liberators that had set out that morning to bomb the major source of oil for Nazi Germany. The men had been told that the mission was vital; it would help end the war a lot sooner.

Only 93 planes returned to base, and 60 of those were so badly damaged they never flew again. Of the more than 1,700 airmen on the mission, 532 were killed, captured, wounded, or listed as missing in action. Of those fortunate enough to make it back to Benghazi, 449 were wounded, many so severely they were unfit to return to active service. One of the pilots who made it back, Lieutenant John McCormick, said later, “There wasn’t a man among us who will ever be the same after that 14-hour jaunt to Ploesti.”

Colonel John R. “Killer” Kane, who landed his plane in Turkey after the mission to Ploesti, described the operation as “the worst catastrophe in the history of the Army Air Corps.” Kane’s navigator, Lieutenant Norman Whalen, said, “We knew it was a disaster and knew that in those flames shooting up from the refineries we might be burned to death. But we went right in.”

None of the planners knew it in advance, but Ploesti was one of the most heavily defended sites in all of Europe. Nobody knew it because reconnaissance flights had been prohibited. Why? Because they might cause the Germans to think that a raid was being planned. But the Germans were already more than well prepared. There were hundreds of antiaircraft guns sited around Ploesti, along with several crack German and Romanian fighter squadrons.

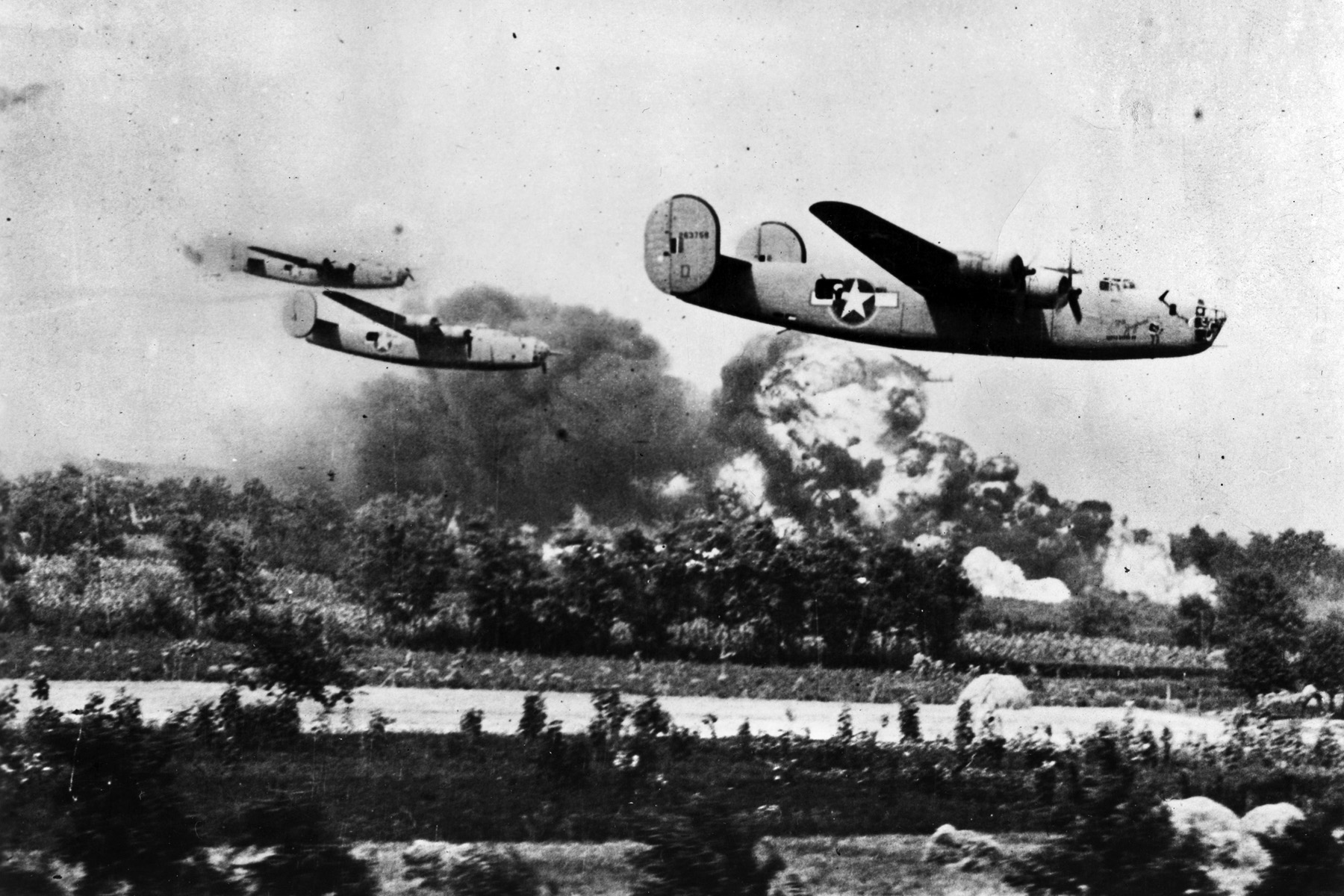

Worse, the lumbering B-24s were ordered to approach at treetop level. To reach the refineries, they had to pass through a narrow valley. Enemy guns lined the route, some situated at a higher altitude than the planes, so they were shooting down at the aircraft. The Germans even had a fast-moving flak train ready to speed down the valley below the waves of bombers and shoot at them from below.

The planes that were able to release their bombs early in the raid sent up columns of burning oil, a deadly screen for the planes that followed. Many of the planes not already damaged by flak burst into flames when they flew through the fire. There was no escape for the crews; they were flying too low to bail out. Lieutenant Richard Britt, a navigator in an exposed front compartment where he could see planes on fire ahead of them, wrote, “When we got there, it was just like an inferno, it was hot as hell. Over the target, when we saw all those planes go down, I just got a don’t-give-a-shit attitude and didn’t care if we went down or not. Be out of the war and all its misery.”

Despite all the suffering and sacrifice, the raid ultimately was of limited value. The damaged refineries were quickly repaired, and a few weeks the Germans had them producing more oil than before.

Gib Hadley flew Hadley’s Harem so low that the bottom of the plane scraped the trees, spewing leaves and branches throughout the fuselage. The waist gunner, 19-year-old Leroy Newton (who would locate the aircraft and Hadley’s remains 51 years later) shouted over the intercom, “Quit trimming the hedges!” Hadley held the plane in formation despite the flak and the shooting flames from the burning refineries.

The bomb bay doors were open; 60 seconds to the target. An 88mm shell tore into the Plexiglas nose, shaking Hadley’s Harem from one end to the other. The explosion ripped open the chest of the bombardier, Lieutenant Leon Storms, and sent shrapnel into the arm of the navigator, Lieutenant Harold Tabacoff. Seconds later the number two engine caught fire, leaving a trail of flame and smoke. Hadley told the flight engineer, Sergeant Russell Page, to go forward to help the navigator when he remembered that the bombs were still aboard. Storms had been hit before he could release them. Page hit the emergency release lever, and the ship bucked in the air with the release of the weight. He bandaged the navigator’s arm and carried him up to the flight deck.

Hadley feathered the burning engine, and the plane took a sudden dive. He and the co-pilot, Lieutenant James Lindsey, pulled up to avoid a crash, and another shell hit the bottom of the fuselage. It buckled into a V-shape and knocked Newton, the right waist gunner, off his feet. He pulled himself upright and back to his gun but was so dazed that he opened fire on a flock of birds, mistaking them for German fighters.

Hadley was able to keep the plane level just above the trees, dodging columns of smoke so thick they blocked out the sun. When they burst free, they spotted two other B-24s. Both were on fire; Hadley and the crew saw them crash. Another one nearby was engulfed in flames, but the pilot was trying to climb slowly to give the crew a chance to bail out. The men inside had to be burning alive. Suddenly the whole plane disintegrated in a ball of fire.

“For a split second I saw that,” Sergeant Christopher Howleger, Hadley’s Harem’s left waist gunner, later told a reporter. “It was the most horrible thing I had ever seen. It is stamped on my mind.” That reporter, 32-year-old correspondent C.L. Sulzberger, on July 16, 1944, wrote a five-page article for the New York Times Magazine titled “The Life and Death of an American Bomber.” Hadley’s Harem became famous until other catastrophes and victories stole the headlines.

Sulzberger described what happened next. “By this time, the Harem was staggering along at 25-feet altitude…. Her hydraulic system was shot out and there was nothing the engineers could do about it. Gasoline was leaking badly from the No. 1 engine into the bomb bay, so Page transferred the fuel from the dead No. 2 engine to No.1.”

Hadley told his men to throw out everything they could to lighten the ship. They tossed out fire extinguishers, Mae West life jackets, parachutes—by this time they were far too low to consider bailing out—and anything else that was not held securely in place. They headed south, flying along with four other crippled ships toward Bulgaria. But ahead of them was a 6,000-foot mountain range that all four planes were barely able to clear. Just as they passed the mountains and flew on over the Aegean Sea, Hadley’s Harem lost another engine. Its speed dropped to no more than 125 miles per hour, and the other planes pulled ahead and flew out of sight, leaving them on their own.

The supercharger on one of the two remaining engines caught fire, and oil started leaking out of the other. They were still 20 miles off the Turkish coast and knew they would be lucky to get that far. Hadley got on the intercom. “Do you want to bail out or try and stick with the ship?” They all agreed. “Let’s stick with her.”

The crewmen took off their shoes to prepare for ditching in the sea. The radioman, Bill Leonard, kept broadcasting their position, and Page, the flight engineer, who was standing behind the pilots, reached overhead to open the escape hatch. By the time they were in sight of land, less than a mile from the coast, the engines quit.

Hadley’s Harem dropped instantly, crashing into the sea with what the survivors later described as a paralyzing shock. A few of the men were knocked unconscious. Page said he bounced like a spring. Water poured in through the flak holes and the open nose, jamming the main escape hatch and trapping them inside the sinking plane. “My God,” Page thought, “am I going to die this way?”

He tried to force the escape hatch open, but it was stuck. As the water rose rapidly in the cockpit, Page saw Gib Hadley and co-pilot Lindsay unstrap their seat belts and flail around, trying to find an opening, but there was none. After another moment, Page saw them die.

He pulled himself into the top turret, took a deep breath of the last remaining air, and plunged down into the water, desperate for an escape route. A glimmer of light caught his eye. It was where the tail of the ship had been sheared off by the crash. Page swam to the surface just as the wreckage of Hadley’s Harem sank.

Seven survivors made it to the beach, helping each other onto dry land. Leroy Newton had a broken ankle, and all of them were bruised. Some had sustained deep cuts and broken bones. They knew they were lucky to be alive, but then they looked around and realized that they were surrounded by more than a dozen fierce looking Turkish fighters, who pointed ancient rifles at the men and gestured for them to kneel.

The Turks, none of whom spoke English, searched each man thoroughly, taking flashlights and anything that could be used as a weapon. And then, to the Americans’ surprise, they gave them cigarettes! Some of the Turks gathered sticks and branches and built a bonfire on the beach so the Americans could dry off. But they had no food or medicine and could do nothing for their wounds and pain until the following day, when a British air-sea rescue boat arrived with morphine, first aid equipment, and a translator.

The locals brought oxcarts and transported the Americans and their Turkish and British rescuers to a village four miles inland. The villagers were welcoming and generous, cooking huge piles of eggs and beans, the survivors’ first meal since the previous morning when Hadley’s Harem had taken off from Benghazi.

The British called for a truck, but when it arrived the villagers had to be persuaded to let the airmen leave. A village elder who spoke English addressed them: “We hear it was a big raid. Congratulations. It was a good job. Your enemies are also ours.”

For the next 50 years, waist gunner Leroy Newton tried to forget about how he had almost died on the Ploesti raid and about the others who did. “I never thought of it as such a big deal,” he said. “In those days, someone else always had a horror story worse than yours.” He worked as a product designer and did not dwell on his wartime experiences until 1993, when he heard there was going to be a reunion of survivors of the doomed mission to Ploesti.

This was the first time Newton had attended a gathering of these veterans, and he was amazed to see among the display of memorabilia a photo of himself and the other survivors of Hadley’s Harem on the beach surrounded by the Turks armed with rifles. That picture and his reunion with two other survivors of the plane released a flood of memories for Newton and awakened a desire to go back to Turkey to search for the plane.

“I’m going to Turkey to find that thing,” he said. “I had nothing else to do. I had a few coins in my pocket and was looking for an adventure…. The seven of us really owed our lives to [Gib Hadley]. It’s miraculous he could fly the thing that far. [He and co-pilot Lindsey] gave me a good 50 years on my life, and I feel this was a good payback.”

When Newton got to Turkey in 1994, he walked the coastline for miles looking for something familiar to help him identify the beach where he and the others had come ashore, but he did not see anything he recognized. On the last day of his frustrating trip, a local newspaper reporter interviewed him about his search and wrote a story about Hadley’s Harem and the American airmen who had survived the crash. By the time the article was published, Newton was back home, disappointed that his trip had been for nothing.

A few weeks later, he received a letter from a retired marine life photographer in Turkey who had read the newspaper article. He told Newton that he and his sons had found the plane in 1972. They had dived to it often when they were making a documentary about turtles. Newton was skeptical at first, thinking it might be a scam, but decided to follow up on this lead. He returned to Turkey, where the diver took him 750 feet offshore. He said the remains of Hadley’s Harem were 90 feet below. “When we got over the site,” Newton said, “I nearly had a heart attack I was so excited.”

The bodies of the pilots, Hadley and Lindsey, were still in the cockpit. Newton found Hadley’s cowboy boots, his twin pearl-handled revolvers, aviator sunglasses, wristwatch, and a 1943 nickel. But then came more delays dealing with the Turkish government to get permission to raise the wreckage of the plane. That took so long that Newton had to travel to Turkey a third time and finance an increasingly expensive salvage operation.

The forward section of the plane, including the cockpit, was raised very slowly using large inflated balloons, a project that took over a month and a half to complete. The bodies were retrieved, positively identified as Hadley and Lindsey through DNA analysis, and brought back to their respective homes for burial with full military honors. The remaining wreckage of Hadley’s Harem rests today in the Rahmi M. Koc Museum in Istanbul, the only plane left of the 177 that flew over Ploesti that day in 1943. The museum, established by a wealthy industrialist, is dedicated to the history of transport, industry, and communications.

Duane Schultz is a psychologist who has written more than two dozen books and articles on military history, including Into the Fire: Ploesti, the Most Fateful Mission of World War II (Westholme, 2008). His most recent book is Evans Carlson: Marine Raider: The Man Who Commanded America’s First Special Forces (Westholme, 2014). He can be reached at www.duaneschultz.com.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments