By Al Hemingway

On a moonless night in January 1944, in the Haute Savoie region of southeast France, the drone from the engine of a RAF bomber could be heard in the distance. Suddenly, three figures parachuted from the aircraft and slowly glided down to earth. A small group of French Resistance fighters greeted the trio at the drop zone and quickly spirited them away to safety.

The three men—a British agent, a French radioman, and a U.S. Marine captain—were on a secret mission for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner of the American Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The operation, dubbed “Union,” was devised to ascertain the fighting capabilities of the French Resistance in the Savoie, Isère, and Drôme areas.

The group was unique and certainly a breed apart. The Frenchman, named “Monnier,” was considered the best communications man in the Maquis, or French Underground. H.H.A. Thackwaite, the Englishman on the operation, was certainly not the image of a spy. He had been a schoolmaster before the war but offered his services to British Intelligence as soon as hostilities broke out between Great Britain and Germany. The remaining member of the group was a dashing U.S. Marine officer named Peter Ortiz. Ortiz had already made a name for himself, which he earned prior to the United States entering the war. As a member of the French Foreign Legion, the brave captain had already escaped from a German POW camp, made his way to the United States, and enlisted in the Marine Corps. Discovering his talents and knowledge of the Germans, the Marines did not hesitate to make him an officer. He was one of a handful of Marines who operated with the OSS to combat the Nazis in Europe.

British Intelligence Unit Provides Inspiration For OSS

Whenever one thinks of the U.S. Marine Corps’ role in World War II, images of Marine infantry units storming the beaches of Guadalcanal, Tarawa, and Iwo Jima in the Pacific come to mind. However, the Leathernecks were present in the European Theater, although few in number, and played a vital role there as well.

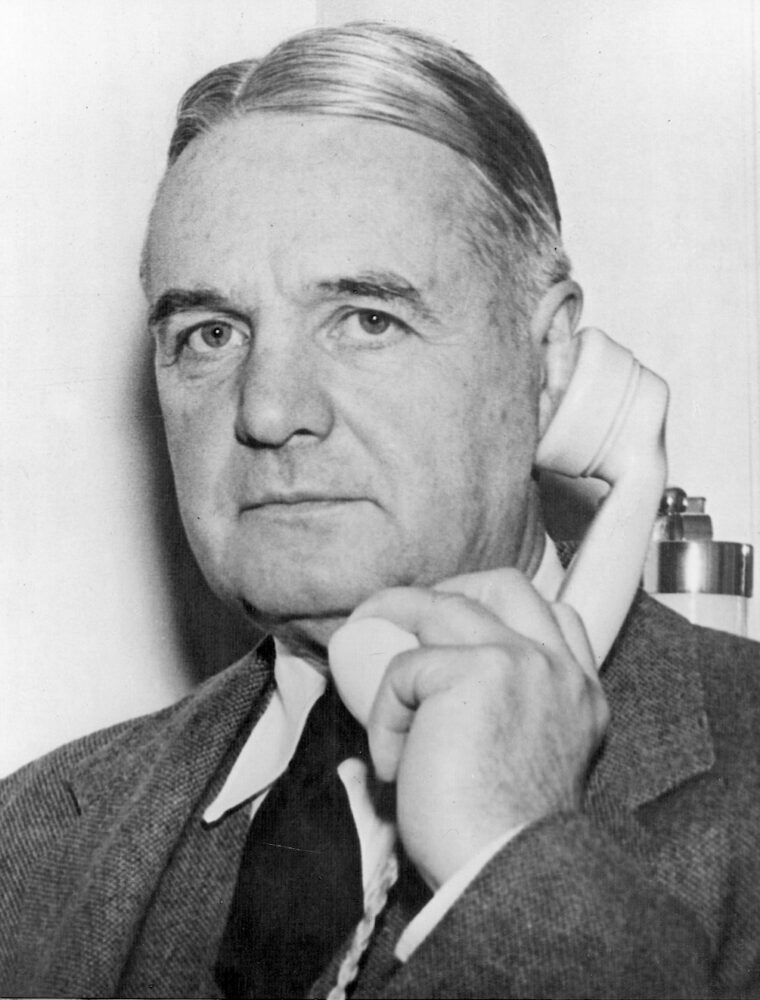

At the outbreak of World War II, the office of the Coordination of Information (COI) was renamed the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). It was headed by the flamboyant William J. “Wild Bill” Donovan, a highly decorated veteran of World War I.

Prior to the war, Donovan was invited to observe British Secret Intelligence Services (SIS) operations. He viewed equipment and procedures that no other American had been allowed to see before. He came away with a new understanding of how an intelligence-gathering group should be organized and operated. In a memo to President Franklin D. Roosevelt he stated: “America needs to form such an organization that would report directly to the President of the United States on all intelligence matters outside the boundaries of the United States.” Roosevelt embraced the idea, and the OSS was born.

The OSS began recruiting members, civilian as well as military, into its ranks. In all, 35 Marine officers and “a considerable number of enlisted Marines” were assigned to the OSS to perform clandestine operations in Europe and Africa.

Prior to the Normandy invasion, the OSS stepped up its secret missions into France to support the French Resistance. One particular area the Allies were watching closely was the Haute Savoie. Rising 3,000 feet above sea level was the Vercors Plateau, an ominous-looking fortress that was 30 miles long and about 12 miles wide. A rugged land, today it is known for its fashionable ski resorts. In nearby Grenoble, the beautiful cathedral of Notre Dame is situated. But during World War II, Frenchmen traveled to Haute Savoie not to pray, but to fight.

The Vichy government, collaborating with the Germans, had begun rounding up all able-bodied males 20 years of age or older to be transported to Germany to work in defense plants. Thousands fled, mainly to the south, to link up with the Underground. They became known as the Maquis, named after a thick bush that grows wild in Corsica.

The Hard Lot Of a Resistance Fighter

It was not an easy life for the resistance fighters. As one leaflet read: “Men who come to fight live badly, in precarious fashion, with food hard to find. They will be absolutely cut off from their families for the duration; the enemy does not apply the rules of war to them; they cannot be assured any pay; all correspondence is forbidden.”

Despite their growing numbers, the Allies were still concerned about Maquis fighting ability and the difficult task of supplying them. Hence, Operation Union was conceived. Thackwaite, Monnier, and Ortiz were selected to parachute into France and evaluate the Maquis. In his book Herringbone Cloak—GI Dagger: Marines of the OSS, Major Robert E. Mattingly wrote, “UNION had a singular task: determine the military capabilities of Maquis units…. Its ordre de mission emphasized that the leaders of such units should be impressed with the fact that organization for guerrilla warfare activity, especially after D-Day, is now their more important duty.”

Although the small band had jumped in civilian clothes, they had brought along their respective military uniforms. By doing this they became the first Allied officers to appear in uniform in France since 1940.

Unfortunately, this posed a problem at times. Ortiz, who despised the Nazis, would proudly wear his Marine uniform in the surrounding countryside as well as in town. The French people loved it, but the Germans were constantly attempting to nab the three agents.

One rainy evening, the colorful Ortiz was sitting in a café. At another table a group of German officers was drinking and toasting “Heil Hitler.” Every so often one of the Nazis would utter an indignant remark about the Maquis and the United States.

Listening to the remarks, Ortiz became increasingly angry. He quietly left the restaurant. However, a few moments later, he returned. Flinging aside his cloak and displaying two .38-cal. pistols, he confronted the enemy soldiers.

“We’ve been drinking toasts to Hitler all night,” he remarked. “Now I want to offer a different toast. To the President of the United States!”

The stunned Germans complied with Ortiz’s demands. Then the Marine captain said: “Now a toast to the United States Marine Corps!”

With that, the tall, handsome Leatherneck strode to the door and disappeared into the night.

Daring Exploits Behind Enemy Lines

Ortiz’s exploits during Operation Union were daring to say the least. He would later become a member of the Most Honourable Order of the British Empire. A section of his citation says: “For four months this officer assisted in the organization of the Maquis in a most difficult department, where members were in constant danger of attack … he ran great risks in looking after four RAF officers who had been brought down in the neighborhood, and accompanied them to the Spanish border.

“During the course of his efforts to obtain the release of these officers, he raided a German military garage and took ten Gestapo motors which he used frequently … he procured a Gestapo pass for his own use in spite of the fact he was well known to the enemy….”

Thackwaite and the others discovered that the French were willing to fight but were grossly ill equipped and ill trained. Money was also in short supply. However, the men of Operation Union went right to work to instruct the band of resistance fighters. As the months passed, the Maquis improved and stepped up their attacks on the Germans in the region. The Haute Savoie territory that once was friendly to the enemy was not “safe” anymore because of these tireless efforts.

In February, three German Panzer battalions struck the Vercors area. Although poorly armed, the Maquis displayed great skill in fending off the Nazis. Because of this, the Germans were forced to reinforce the assault troops with two divisions in an attempt to isolate the plateau.

It soon became apparent to the OSS and British Intelligence that if the French Underground were to enjoy any success against the Germans it would have to be supplied on a grand scale.

By late May, the men of Union had been withdrawn. The following week the Allies invaded Normandy. The push was on to free occupied France—and the Germans knew it as well.

In mid-July, La Chapelle en Vercors was shelled. On July 14, American Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers dropped 1,500 canisters of arms, ammunition, and other supplies to the embattled Maquis. According to Mattingly, “The inhabitants ran out in the streets shouting and waving to the fliers.… Thirty minutes later the Germans began bombing and strafing the town. This prevented the men from collecting the containers. Only at night was it possible to gather 200 of them. The Germans also started the destruction of La Chapelle en Vercors. The town was ablaze and [enemy] fighters machine-gunned people endeavoring to save their belongings from their homes.”

Nearly a week later, the Germans assaulted Vassieux with glider troops. The fanatical soldiers of the Waffen SS spearheaded the attack and seized the town. The Maquis counterattacked the Nazis on four separate occasions but were driven back. With no air or artillery support, the resistance fighters took horrendous casualties. In retribution, the Germans began killing innocent civilians.

The situation in the Haute Savoie was worsening. It was decided to airdrop more supplies to the Maquis. Also, Ortiz, recently promoted to major, would lead the next group into enemy-held territory.

On a sunny Sunday in June 1944, Marine Sergeant Jack Risler and some of his friends would often go to Speaker’s Corner at Hyde Park in London on a 48-hour pass. Here, “soapbox orators” would speak passionately on a variety of subjects—everything from the end of the world to antigovernment propaganda.

Suddenly the Marines heard a voice behind them say, “What are you guys doing?” Turning around, they were face to face with Peter Ortiz. The Marine officer had just returned from Union. He informed the group that he was going back. Risler and his friends were eager to join Ortiz, who told them to be patient and he would find out if they could accompany him.

Risler had been an instructor at Parachute School in New River, NC, and he had been stationed at Riggers School in Lakehurst, NJ. Bored with these assignments, he requested a transfer. Then one day he was called to the office of his commanding officer and asked “if he wanted to do something different.” Eager for a new assignment, the Marine NCO quickly agreed. From there he was sent to the Congressional Country Club in Washington, DC. The establishment had been commandeered by the OSS for the duration of the war as a school for its agents.

”Dangerous Dan” Trained OSS Recruits In Self Defense

British Major William “Dangerous Dan” Fairbairn, former chief of police in Shanghai, China, was the head instructor. Fairbairn had had a colorful career. In addition to his many military accomplishments, he had designed the Fairbairn stiletto described as a “real fine knife” by one OSS operative.

“Fairbairn trained us in judo,” recalled Risler. “He was 45 years old. He would give you one of his stilettos and tell you to come at him. We didn’t want to hurt him. However, you would find yourself looking up at the sky when he got done with you.”

The group of 16 agents—eight Marines and eight soldiers—was ordered to England after successfully completing training in Washington, DC. They were quartered at the Dunham House in Altringham, south of Manchester, for additional instruction.

Here they learned the British style of jumping. The American parachutes were designed differently from their British counterparts. In the American chute, the risers and suspension lines came out first, then the canopy; it was the opposite in the British chute. American chutes also had three snaps, one on the chest and another on each leg. The Brits jumped from a hole in the bottom of the aircraft while the Americans leaped from the side of the plane. Most U.S. personnel preferred the English method of jumping. The Brits had less of an opening shock, and the parachutist got out of his chute much quicker. The only drawback to the British style was the 3/8-inch cable they used instead of webbing for their static line. Caution had to be used so that the cable did not inadvertently wrap itself around someone’s arm or leg, which could result in a serious mishap to a jumper.

Several days after meeting Ortiz, Risler was summoned to Kensington Palace Mansions. He had been selected for Operation Union II, but he knew little of the details. Ortiz, Risler, U.S. Air Force Captain John Coolidge, Gunnery Sgt. Robert La Salle, and sergeants Charles Perry, John Bodnar, and Fred “Fritz” Brunner met at Baker Street, headquarters of British Intelligence. An additional member of the operation, Joseph Arcelin, a French Resistance fighter codenamed Jo-Jo, would link up with the group in France. At Baker Street, the men were given a mountain backpack, personal supplies, a Colt .45 automatic pistol, a Winchester semiautomatic carbine with a metal folding stock, a Fairbairn stiletto, and a map case.

From there, the group traveled to Knettishall Airfield, about 60 miles northeast of London. Here they were handed a silver hip flask of cognac, Lucky Strike cigarettes with no markings on the pack, and the equivalent of $1,000 U.S. in French francs. Ortiz was also given a suitcase with one million francs to be used to aid the Maquis.

Finally, the agents were briefed on their mission. The purpose of Union II was not only to train the Maquis but also to be in direct contact with German troops. In addition, Allied planes were to drop 864 containers of supplies to the French Underground in the Vercors Plateau area on August 1. The containers held 1,096 Sten guns, nearly 300 Bren automatic rifles, 1,350 Lee-Enfield rifles, over 2,000 Mills anti-personnel grenades, more than 1,000 Gammon grenades, 260 pistols, 51 PIAT antitank weapons, over two million rounds of ammunition, several tons of explosives, medical supplies, clothing, and food. This drop would equal the one parachuted in on July 14, just two and a half weeks earlier. These were the two biggest parachute supply drops of the war.

Air Drop Into Occupied France

On Tuesday morning, August 1, B-17s of the 388th Heavy Bomber Group took off from Knettishall Airfield carrying the men of Union II. Painted black, the B-17s had a fighter escort of North American P-51 Mustangs accompanying them on their journey.

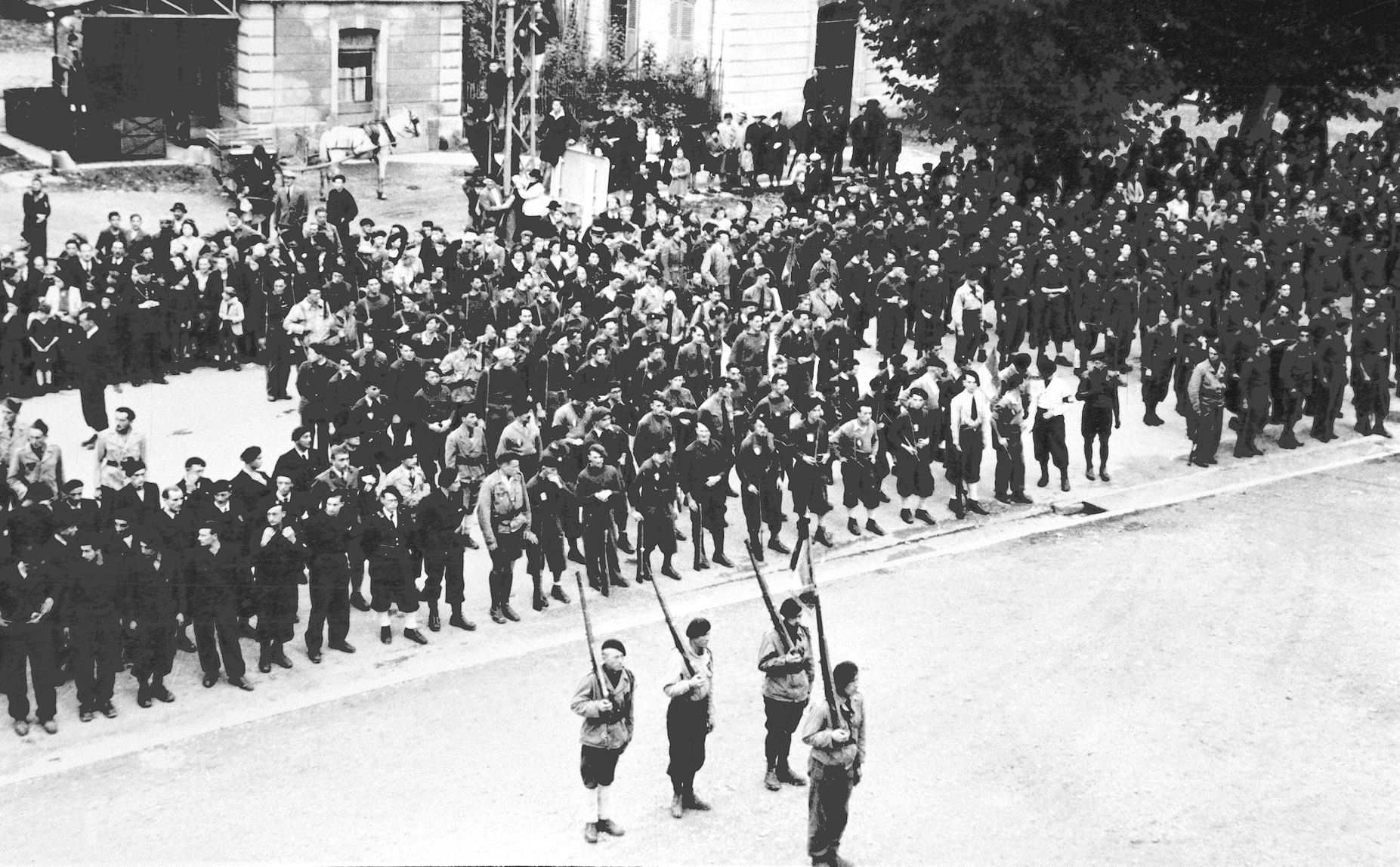

A total of 78 aircraft was soon over the drop zone. Both containers and agents jumped in 60-second intervals from an altitude of 400 feet between the Plateau des Glierres and the Plateau des Vercors. A company of Maquis greeted the men as they made it safely to the ground.

As Risler gathered his chute, a French Resistance fighter rushed up to him and kissed him on both cheeks. However, tragedy struck from the outset of the operation. Sergeant Charles Perry’s chute did not open, and he was killed in the fall. A malfunction in the static line caused it to snap, resulting in his untimely death. Also, Gunnery Sgt. Robert La Salle hurt his ribs and spine upon impact.

Maquis members wasted no time in collecting the ammunition and supplies. To confuse the Germans, the townspeople of nearby Albertville informed them that two battalions of American paratroopers had landed. That misinformation allowed the Union II members to evade the enemy.

After burying Perry with full military honors, Ortiz and his men started training the men of the Bulle Battalion of the Maquis. The unit was named after its leader, Captain Jean Bulle, a local Maquis hero. Disaster almost struck again when one young Frenchman picked up a Sten gun and began firing wildly in all directions. As bullets whizzed around, everyone dove for cover. Luckily, no one was injured; however, the unfortunate resistance fighter did shoot his own toe off in the accident.

After a week of familiarization with the weapons, Ortiz’s group began patrolling the area. The crafty Marine established Maquis ambush sites, usually selecting a curve in the road or a small rise nearby. He had memorized all the various German units and would stay hidden as they passed, counting vehicles, troops, and so forth.

On August 12, Ortiz conferred with the Maquis and made the decision to utilize them to drive the Nazis from the Tartenaise Valley. A few days later, Union II, accompanied by a few Maquis, entered a hamlet called Montgirod. The team was nervous because a small German spotter plane had been circling overhead. Nearby, Captain Bulle had nearly 200 men poised to do battle.

In the early afternoon, German mortars began finding their mark. As the shelling increased in tempo, it was decided to pull back. Several resistance fighters were wounded and evacuated, but two other more seriously wounded Maquisards were left in the town church.

As the Marines withdrew, they took to the steep hills surrounding the village to evade the German forces attempting to cut them off. “The German patrols came so close,” remembered Risler, “I’d say 30 to 40 feet—both foot and motorcycle patrols. They gave themselves away, though, because they liked to sing and we could hear them coming. We forded the Isère River and went to the village of Centron. It was midnight and we stopped to rest, and damn if another German patrol didn’t come by. They had the area pretty well surrounded. We just froze. They didn’t see us and they just went by.”

Meanwhile, back in Montgirod, the Nazis uncovered the pair of wounded Maquis. They were promptly shot, and the church was put to the torch. The enemy began rounding up hostages in retaliation.

Union II was still dodging the Germans. On the morning of August 15, the band of agents was just outside the town of Longefoy. Ortiz instructed the party to stay hidden while he made his way to the hamlet. Making contact with the mayor, Ortiz explained the group’s precarious position. He returned to the rest of the party and brought them back to the hamlet to be fed and billeted for the night.

The following morning, the men of Union II made their way back to Centron. They crossed the bridge in single file: Ortiz, Bodnar, Risler, Coolidge, Brunner, and Arcelin.

Suddenly, a German armored patrol rounded a bend in the road and saw the party in the open. As the agents tried to escape, Coolidge was wounded in the leg but he and Brunner still managed to flee to the river. Arcelin was caught as he tried to hide in an apple orchard. Ortiz, Risler, and Bodnar ran back to Centron. Running from house to house, they were taking the bulk of the German fire. Risler’s backpack was full of bullet holes as he tried to negotiate a drainage pipe to find safety. Miraculously, he was not wounded.

The German infantrymen were now concentrating their efforts on Ortiz’s little band. The inhabitants of Centron were begging the Marines to surrender to avoid German reprisals. Years later Ortiz would write: “Since the activities of Mission UNION and its previous work were well known to the Gestapo, there was no reason to hope that we could be treated as ordinary prisoners of war. For me personally the decision to surrender was not too difficult. I had been involved in dangerous activities for many years and was mentally prepared for my number to turn up. Sgt. Bodnar was next to me and I explained the situation to him and what I intended to do. He looked me in the eye and replied, ‘Major, we are Marines, what you think is right goes for me too.’”

Ortiz hollered out to the Germans to cease their firing. When it finally eased up, he boldly strolled out to the street. An old French woman raced toward him and threw herself in front of Ortiz to protect him. Gently pushing her aside, the Marine major kept walking toward the Nazi lines with machine gun bullets “kicking up dust around him.”

Shouting in German, Ortiz explained that his group would surrender as long as there were no acts of vengeance directed toward the townspeople. Ortiz explained that they were innocent and had not given them any support and that his group was “just passing through.”

When the German officer agreed to the terms, Ortiz ordered his men to come out and called them to attention. He then told them not to surrender any information except name, rank, and service number.

Arcelin, who had already been captured, was brought forward to be with the rest of the group. He had put on Perry’s uniform and pretended to be a Marine named George Anderson. The deception worked in spite of the fact Arcelin could not speak any English.

However, the German officer in command became quite upset when he learned that a mere four men, armed with just .45s and carbines, had held off an entire battalion. Not satisfied, the enemy soldiers searched the rest of the buildings for additional troops but soon learned that this was the entire contingent.

Ortiz’s group was then transported to German headquarters at Bourg-St. Maurice. Everyone claimed they were paratroopers who had jumped as a part of Operation Anvil, the invasion of southern France. Again, the trick worked and the enemy even treated the group with more respect.

The Marines, including Jo-Jo Arcelin, were then handed over to a Major Kolb, a World War I Iron Cross recipient. Although Kolb was aware of the true identity of his prisoners, for some unknown reason he did not turn over his “prize catch” to the Gestapo.

“He quickly proved that he knew a great deal about me,” Ortiz later wrote. “In great detail and accurately he described our air operation, the burial ceremony for Sergeant Perry, various engagements and the manner and position of our movements since leaving Montgirod. These, he said, had been reported by a shepherd who was one of his field agents.”

The Union II men were quickly whisked away to avoid any attempts by the Maquis to liberate them. Also, Allied troops from Operation Anvil were a mere 15 miles away.

Arriving in Chambury, Ortiz asked for an interview with the commanding general, Karl Pflaum. When his request was granted, the nervy Marine major marched into Pflaum’s office and demanded that the 157th Alpine Division surrender to Union II. Pflaum “blew his stack,” and told Ortiz to get out of his office before he had him shot. Needless to say, the surrender did not take place.

By late September 1944, the captured Marines were interned at a naval POW camp, Marlag/Milag Nord, situated in the tiny German village of Westertimke, just outside Bremen. The camp prisoner contingent, comprised mainly of British seamen and British Royal Marines, included only 13 American prisoners.

As the Allies pushed toward Berlin in 1945, fighting soon erupted near Westertimke. Waffen SS troops placed artillery pieces in the camp knowing Allied soldiers would not fire directly into the compound fearing friendly casualties. To avoid injury, the prisoners dug foxholes. Despite digging in for safety, Arcelin was wounded by shrapnel. Fortunately, his wounds were not life threatening.

Liberation

Finally, on April 29, 1945, the British 7th Guard’s Armored Division liberated Marlag/Milag Nord. As the sound of bagpipes was heard, the cocky Ortiz presented himself to a British naval officer attached to the Royal Marines and said he “wanted to join his unit in order to bag a few more Germans before hunting season closed.” Although the offer was appreciated, the POWs were asked to climb aboard trucks to be transported to the rear area.

For his outstanding bravery, Ortiz was awarded his second Navy Cross. Risler, Bodnar, and LaSalle were presented with the Silver Star for gallantry during the Union II operation. Sadly, some of the heroic Allied combatants were not so fortunate.

“Fritz Brunner, who escaped from Centron, was later killed on another mission,” said Risler. “Captain Jean Bulle was executed by the Germans. He entered Albertville under a flag of truce to ask for their surrender and, instead, they shot him. They made him kneel down and they shot him in the back of the head. The Germans considered him a terrorist and not a regular soldier.”

After the war, Hollywood made a movie entitled 13 Rue Madeleine starring James Cagney and Richard Conte. The film was loosely based on the exploits of Union and Union II in France. Ortiz was the film’s technical adviser. In 1988, the hero of Union and Union II passed away after a long bout with cancer. He was indeed a legend in the OSS.

In May 1984, Jack Risler and John Bodnar returned to France to commemorate the 40th anniversary of Union II and the great parachute drop. They visited the grave of Charles Perry. The grateful citizens of Albertville placed a bronze plaque at his grave and hold a memorial service every year in his honor.

Risler and Bodnar were treated as heroes by the townspeople on their return trip to the Haute Savoie region. The French people had not forgotten the sacrifices they had made so many years earlier so they could be freed from the tyranny of the Nazi regime.

“We were wined and dined,” said Risler. “It was a good feeling.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments