By William E. Welsh

Venetian military engineer Gabriel Tandini listened intently in the semi-darkness of the Knights Hospitaller counter-tunnels beneath the walls of Rhodes for sound of Turkish sappers trying to dig under the city’s walls. Tandini used a shallow drum covered with tightly stretched parchment similar in size to a tambourine as an early-warning device. When the Turks began digging with their spades, tiny bells on the listening device would begin jingling. Tandini and his skilled miners would then dig in the direction of the Turkish tunnel they had discovered. Once they were close to it, they would detonate explosives to destroy the head of the Ottoman tunnel.

The Turks had failed in 1480 to capture the fortress of Rhodes from the Knights Hospitaller. One of the reasons for the failure was the incompetent effort put forth by Mesih Pasha, a Byzantine Greek who had converted to Islam and served as the grand vizier to Sultan Mehmed II. Mehmed’s great-grandson was Sultan Suleiman I.

Like his great-grandfather, Suleiman also found the Knights Hospitaller stronghold at Rhodes to be an affront to the Ottoman Empire given that it was situated just 11 miles from the southern shore of Ottoman-controlled Anatolia. Suleiman vowed to avenge the defeat his esteemed ancestor had suffered at the hands of the Roman Catholic military order. To avoid the mistake of entrusting such an important expedition to a subordinate, Suleiman set sail at the head of nearly 200,000 soldiers in 700 ships that weighed anchor off the northern shores of the island of Rhodes on June 26, 1522.

Suleiman “the Magnificent” was born in Trebizond on November 6, 1494, during the reign of his grandfather, Sultan Bayezid II. Suleiman’s father, Selim I, overthrew Bayezid in 1512. The rebellion was significant because it was the first time that an Ottoman prince openly rebelled against his father with an army. Selim “the Grim” exiled Bayezid and murdered his brothers and nephews to ensure there was no male relative in his immediate family to contest his rule. Despite his familial reign of terror, Selim doubled the size of the Ottoman Empire through his conquest of the Mamluk Sultanate in 1517.

Suleiman succeeded his father upon his death in 1520. The 25-year-old sultan inherited an empire that straddled three continents, covered one million square miles, and possessed 12 million inhabitants.

Suleiman’s first score to settle was with the Hungarians. Sultan Mehmed II had tried unsuccessfully to capture the Serbian fortress of Belgrade in 1456 but was outwitted by the brilliant Hungarian commander John Hunyadi. Suleiman marched north in February 1521 at the head of 100,000 troops and a siege train of 300 cannons. Suleiman divided his forces. He besieged the fortress of Sabac and detached part of his army under grand vizier Piri Mehmed Pasha to lay siege to Belgrade. After the fall of Sabac, the main army joined the siege of Belgrade. When Ottoman sappers tunneling under Belgrade’s walls succeeded in blowing up the main tower of the fortress, the Christian garrison surrendered.

Having captured Belgrade, Suleiman decided to address the long-standing problem posed by the presence of the Knights Hospitaller at Rhodes. When his first threatening letter to Grand Master Philippe Villiers de L’Isle-Adam failed to compel the military order to negotiate with him, he sent another letter. In his second dispatch he accused them of “monstrous injuries” and implored them to surrender the island and its fortress, stating that he would allow the brother-knights to “depart in safety with your most valued possessions.”

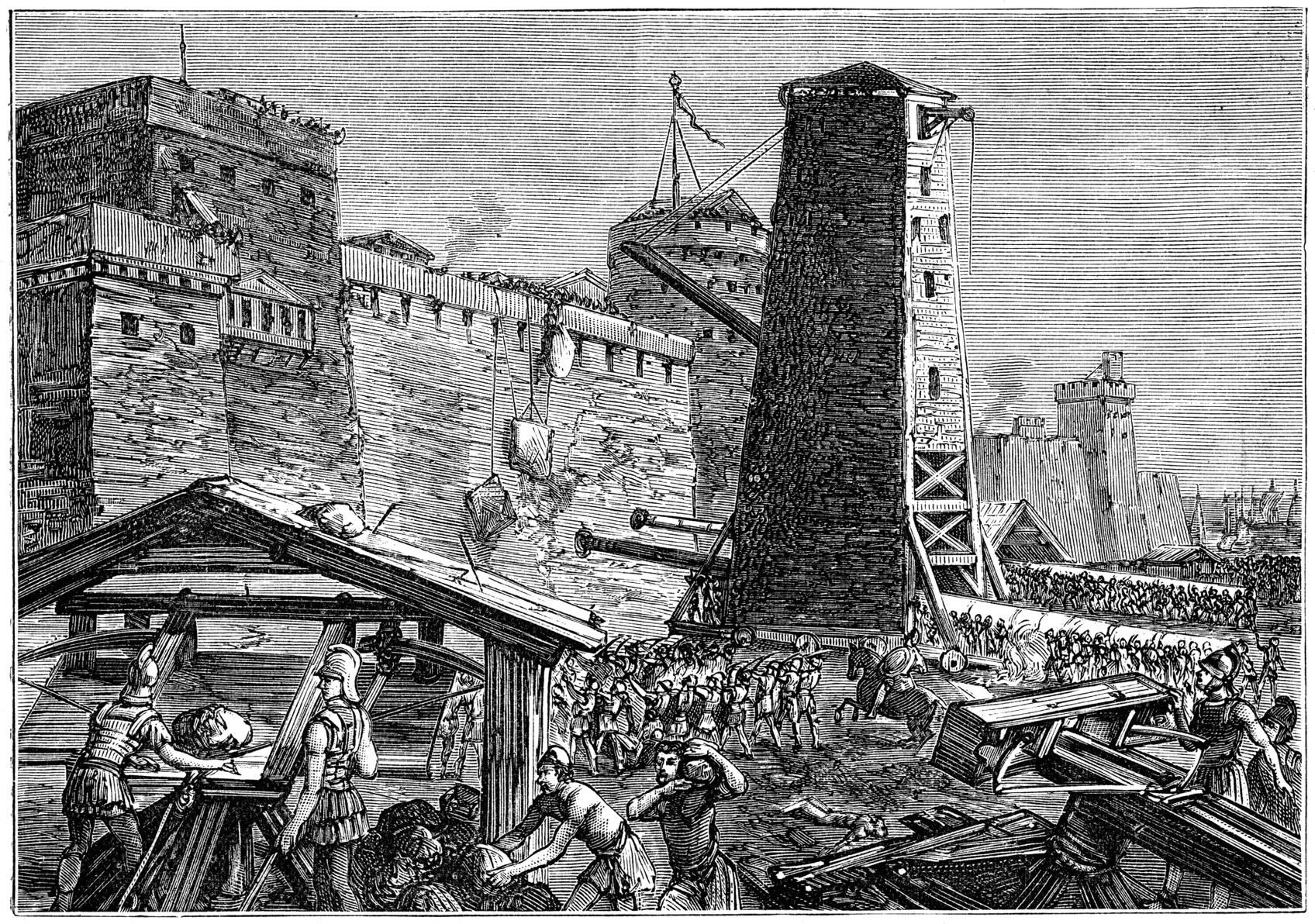

When the sultan received no reply, he sailed at the head of an army nearly twice the size of the one that had captured Belgrade. But the fortress of Rhodes was stronger than the stronghold of Belgrade, for the Knights Hospitaller had been continually improving its defenses since they arrived in the early 14th century. In anticipation of the Turkish siege artillery, the outerworks and towers of the fortress had been fashioned into bastions better able to absorb the stone balls fired by the enormous Turkish bombards. Nevertheless, the garrison was paltry compared to the Turkish host. The grand master had just 700 knights and 2,000 mercenaries.

The Turks succeeded in breaching the outer defenses of the fortress in September after bringing down a section of the wall through mining. The knights repulsed the attack but knew full-well that time was not on their side. The grand master entered surrender negotiations in December. Suleiman agreed to allow the knights to depart unmolested; however, the janissaries took it upon themselves to defile the sacred sites in the city. On January 1, 1523, the Hospitallers departed. They eventually found a new home in Malta when Holy Roman Emperor Charles gave them the strategically located island in 1530.

After driving the knights from Rhodes, Suleiman turned his attention once again to Hungary. He planned to use Ottoman-controlled Serbia as a springboard into Hungary. He had every confidence that his powerful army could vanquish the army of 20-year-old Hungarian King Louis II, who would need the assistance of other Catholic powers if he were to meet the Ottoman army on equal terms.

Louis, who ruled Hungary, Croatia, and Bohemia, called up forces from his regions, but received no forces from other Catholic powers. The 30,000-strong Ottoman vanguard of Rumelian troops under Ibrahim Pasha crossed the Drava River uncontested and occupied a line of ridges on the south side of the plain of Mohacs, where Louis waited with his 14,000 cavalry, 16,000 infantry, and 85 cannon. Suleiman followed behind the Ottoman vanguard with 50,000 Anatolian troops.

Hungarian commander-in-chief Pal Tomori decided to attack before the Ottoman main army arrived in the hopes of defeating the vanguard. Louis accompanied the army, given that the future of his realm was at stake. The Hungarian heavy cavalry smashed through the Rumelian cavalry. By that time, the Anatolian cavalry had arrived to reinforce the Ottoman vanguard. The Hungarian armored cavalry smashed the Anatolian cavalry, as well. Believing the day was won, they attacked the Turkish center, where the Ottomans had chained together their cannons. By that time, Ottoman detachments of infantry and light cavalry began to assail the flanks and rear of the Hungarian army. The Hungarians tried to retreat but were annihilated. Louis drowned during the chaotic retreat in a flooded tributary of the Danube River.

In less than two weeks’ time, the Ottomans had secured Buda, and the Ottoman victory at Mohacs divided Hungary. The Ottomans controlled southern Hungary, while the Hapsburgs controlled northern Hungary, which became known as Royal Hungary.

Suleiman marched on Vienna three years later. Although the defenses of the great city, which was the seat of the Holy Roman Empire, were weak and outdated, it boasted a garrison of 16,000 experienced troops. Hapsburg Emperor Charles V entrusted its defense to 70-year-old Count Nicholas of Salm, a veteran of the Burgundian Wars.

After a painstakingly slow advance from Istanbul, the Ottoman army arrived before the walls of Vienna on September 26, 1529. The wet weather had sided with the Austrians, producing a logistical nightmare for the Ottoman Turks, who had struggled along muddy roads on their 900-mile march with their artillery and supply wagons. Because of the conditions, Suleiman was only able to field 300 small guns that lacked the power necessary to open breaches in the six-foot-thick city walls. The defenders’ strategy of constructing earthen and wooden walls and ramparts inside the fortress as a second line of defense proved to be a sound one.

The Ottomans tried to mine the walls, but half of the Austrian garrison sallied forth on October 6 and overran the Turks’ forward lines, killing as many sappers as they could before withdrawing. The Turks succeeded, though, in breaching the outer walls on several occasions, but Imperial pikemen fought off the sultan’s sword-wielding elite janissaries. Having lost 20,000 men, Suleiman raised the siege and withdrew south on October 14. The Ottoman siege of Vienna marked the apogee of Ottoman power. Suleiman’s failure to capture the city had revealed weaknesses among his officer corps, as well as within the ranks of his janissary troops.

Suleiman launched his third invasion of Hungary in 1532 and besieged the stronghold of Koszeg, which was situated in western Hungary 60 miles south of Vienna. The fortress was held by Croatian Captain Nikola Jurisic, who had 700 soldiers but no artillery and only a few arquebuses. A gifted leader, as events would show, his paltry force held off the vast Ottoman host for three weeks, after which the Ottoman army again withdrew in defeat.

Afterwards, Suleiman campaigned against the Persians from 1534 to 1538. During that time, he decisively defeated Safavid ruler Shah Tahmasp I, who as a military leader was no match for Suleiman.

The Ottoman sultan had allowed southern Hungary to exist as a tributary principality under the direct rule of the Transylvanian voivode, but in 1541 he finally annexed the country, and it became part of the Ottoman Empire.

The following year he marched up the Danube and invaded Austria again in retaliation for Archduke Ferdinand’s forays into Hungary. This time, his forces prevailed, and he successfully besieged two strategic fortresses, after which he entered into a truce with Emperor Charles V in 1544. Returning to the east, Suleiman campaigned in Armenia and Georgia. Suleiman also sided with his son Selim against another son, Bayezid, who’d rebelled against him. After he was defeated in the field, Bayezid took refuge in Safavid Persia, but Suleiman bribed Shah Tahmasp to execute Bayezid, which he did in 1559.

Holy Roman Emperor Charles V had won a stunning victory against the Ottomans at Tunis in 1535. In the years that followed, the Knights Hospitaller at Malta aided the Spanish navy. As they had at Rhodes, the knights improved Malta’s defenses. Because the knights had allowed Spanish fleets to rest, refit, and re-arm in their galley harbor, Malta incurred Suleiman’s wrath anew. The sultan dispatched Grand Vizier Mustafa Pasha to capture the port in May 1565. The grand vizier not only had the support of the Ottoman navy, but also of the Barbary corsairs. But the Turks squandered their strength in repeated attacks on Fort St. Elmo, which guarded the harbor. Although reinforced by the Pasha of Algiers, the Turks still could not capture the walled port. The Ottoman army withdrew in September 1565. The debacle at Malta was one of the greatest disappointments of Suleiman’s reign.

Suleiman undertook his seventh military campaign in Hungary, and the thirteenth of his career, in summer 1566. His ultimate goal was to besiege Vienna again, but the 72-year-old sultan allowed himself to be diverted from his ultimate objective. When he reached Belgrade in late June, he was informed that the southern Hungarian stronghold of Szigetvar had fallen to Hungarian Captain Miklos Zrinyi. Angered by Zrinyi’s success, Suleiman turned west in a bid to retake Szigetvar. The sultan arrived at Szigetvar on August 5.

The initial phase of the siege went well. The Ottoman Turks captured the old and new towns and drove the defenders into the citadel despite having to fight through a maze of rivers, streams, and marshes. Zrinyi held out, even though he had only 600 men left. Just as the fortress was about to fall to the Turks, Suleiman breathed his last breath. He died in his tent, and the senior commanders and his staff kept the news from the troops lest they should lose heart and refuse to keep fighting.

When the Turks made their final assault, the defenders exploded the contents of their magazine among the attackers. Zrinyi was killed by two bullets in the chest leading a charge during the final phase of the siege. Despite the Hungarians’ heroic sacrifice at Szigetvar, the Turks captured the fortress.

Suleiman’s death was not made public until his lifeless body was safely in Istanbul. Suleiman is the only ruler ever to have been given the sobriquet “the Magnificent.” He built upon the successes of his predecessors, and during his reign the Ottoman Empire reached the pinnacle of its power. In the wake of his death, the empire would experience more setbacks and military defeats than ever before.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments