By Mike Phifer

British soldiers fixed their bayonets and waited tensely in the trenches for the order to go over the top. Officers glanced at their watches and counted down as the minutes and seconds ticked away to zero hour. “Five minutes to go!” shouted Lieutenant Ulrich Burke of the Devonshire Regiment down the right and left of his trench sector. Other officers along the whole British line were doing the same.

At 3:50 a.m., the early morning came alive as thousands of British artillery pieces opened up. “A long, jagged line of flame burst from the ground [in front of me],” recalled Captain Thomas Owtram of the King’s Own Royal Lancaster Regiment. “I blew my whistle and shouted. Men struggled stiffly to their feet, and we advanced until the shells were bursting only about 50 feet in front of us.”

Along the whole British line, other officers were blowing their whistles and shouting the same orders. Thousands of British troops climbed out of the trenches and began to follow the creeping barrage. “The noise was tremendous, and shout as hard as you could, it was impossible to make the man next to you hear,” wrote Stanley Bradbury of the Seaforth Highlanders.

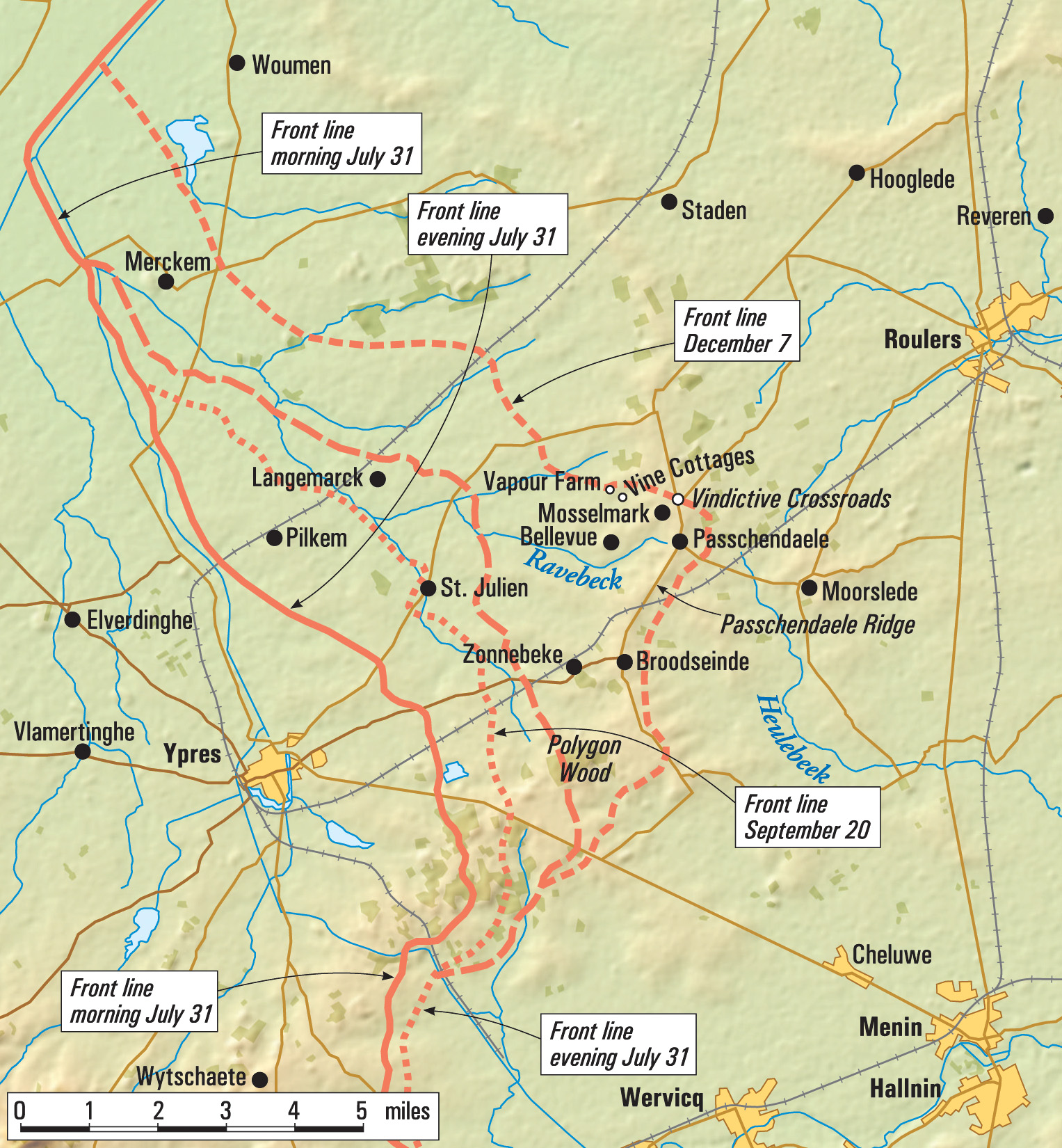

Hugging the curtain of shells, four corps from the British Fifth Army had just spearheaded a major attack on July 31, 1917, in the Ypres Salient. The Third Battle of Ypres had just begun.

Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, the British commander-in-chief, had strong hopes for this offensive, believing the campaign would end the war. It would be followed that autumn by the British and Commonwealth forces’ assault on Passchendaele, which would mark the final phase of the Third Battle of Ypres.

Although the British held Ypres, the Germans controlled the wooded ridges that dominated the agricultural town, mostly from the east and south.

The high ground included Messines Ridge to the south and continued northeastward to Passchendaele Ridge. Lesser ridges or rises named after other towns also were held by the Germans. Holding three sides of this salient, the Germans launched the first War’s major gas attack in April 1915 in an attempt to rub out this Allied-held bulge. A green Canadian division managed to plug a gap in the line when colonial French troops gave way. The Allies would continue to hang on to the Ypres Salient for the next two years.

Besides being symbolic of Allied determination to win the war, the Ypres Salient was strategically important to the British, as the channel ports vital to their supply line to England were a short distance away.

Similarly, holding the high ground dominating the salient was important to the Germans. Twelve miles northeast of Ypres was the vital rail center of Roulers, which the Germans needed to keep in their hands. They also needed to protect the Belgian coast, where German submarine bases were located at Ostend and Zeebrugge.

For some time, Haig had been nurturing plans to launch an offensive from Flanders that would shatter the German lines, capture Roulers, and free the Belgian coast, aided by an amphibious landing. Haig believed the Germans would be forced to stand and fight, since they did not want to lose their ports on the south side of the English Channel and the rail center. In Haig’s thinking, the German resistance would be worn down, especially after the casualties they had suffered in the bloodlettings at Verdun and the Somme.

The first phase of Haig’s plan was launched when Sir Herbert Plumer’s Second Army conducted a fierce attack against Messines Ridge. Greatly aided by 19 mines that contained over a million pounds of explosives and devastated the German defences, the British took the ridge. This victory secured the southern wing of the Ypres salient, allowing Haig to focus on the main part of his offensive to the east.

Before this happened, though, Haig traveled to London, where he met for three days beginning on June 19 with the Prime Minister David Lloyd George, Chief of the Imperial General Staff Sir William Robertson, and members of the War Cabinet to discuss his plan, which he hoped would end the war. George was not keen on Haig’s plan; instead, he preferred sending troops and equipment to the Italian Front with the hopes of not only weakening the Germans, but also forcing the Austrians out of the war. But Haig, who had the support of Robertson, believed the Italo-Austrian front to be nothing more than a sideshow. Haig insisted that the Germans had to be defeated in Flanders. First Sea Lord Admiral John Jellicoe also favored Haig’s plan because he wanted the German U-boat bases on the coast of Belgium destroyed. This objective had become imperative, because the Germans U-boat campaign was taking a heavy toll on Allied shipping.

When all opinions had been heard, Haig received permission to begin to prepare for his Flanders offensive pending final approval by the War Committee, which gave its approval on July 20. The committee issued a stern warning to Haig not to allow his offensive to turn into another debacle similar to the Somme offensive of 1916.

Haig brought in Sir Hubert Gough and his Fifth Army to spearhead the northern operation—the second phase—of his plan, which was to capture the high ground east of Ypres, including the dominating Passchendaele Ridge, and shatter the German position in Flanders. Gough’s attack was to be supported by Plumer on his right and by the French First Army on his left. Once the Passchendaele Ridge had been captured, Gough was then to continue attacking northeast onward to the Belgian coast. Sir Henry Rawlinson’s Fourth Army would aid along the coast with an amphibious landing.

Gough began to organize his army for the upcoming assault, which was scheduled for July 25 but then postponed until July 31. The troops dug support trenches, built roads, laid telephone cables, and stockpiled tons of supplies. They also gathered hundreds of thousands of rounds of ammunition for 3,000 guns. These guns were brought in at night and positioned on timber platforms to keep them from sinking into the mud. The Allies bombarded German positions during the second half of July with upwards of four million shells.

The Royal Flying Corps battled enemy aircraft overhead in a bid to dominate the air space to a depth of five miles over the front. “Never before had we seen such masses of aircraft and air combat as at the front above Ypres,” wrote German soldier Johann Schardel.

The Germans had multiple layers of trenches in the Ypres salient that were studded with pillboxes and blockhouses. The Germans also had 1,500 guns in the sector. By the third year of the war on the Western Front, the Germans employed the concept of an elastic defense. This entailed putting light forces in the frontline trenches and keeping the bulk of their forces further back and ready to counterattack immediately.

The German lines took a terrible pounding from the two-week British bombardment, which destroyed support trenches and smashed barbed wire. The shelling also churned the up the terrain with more shell holes and destroyed the delicate drainage system of an area with a notoriously high water table. The German infantry suffered heavy casualties, as did their guns, destroyed by accurate British counter-battery fire. Ominously for the British, though, many of the enemy pillboxes remained intact.

“The whole of Flanders earth moved and appeared to be in flames,” wrote General Hermann von Kuhl, Rupprecht’s chief of staff, when the British bombardment began on the morning of July 31. Haig committed the II, XIV, XVIII, and XIX corps of the Fifth Army to his offensive. Two French corps and three corps from the British Second Army supported the main attack on the left and right, respectively.

As the troops moved forward in the darkness, crawling over the pock-marked terrain, in support of them were 136 tanks of the Tank Corps. As the offensive progressed, the British found that the tanks were of limited use. They broke down frequently due to mechanical failure, at which point the Germans could easily knock them out with their artillery.

At first the attack went well as the troops of the Fifth Army pushed toward their first objective, 1,000 yards forward, which was known as the Blue Line.

By early afternoon on the first day, Gough’s attack began to slow down when the Germans launched a series of furious counterattacks. In vicious close-quarters fighting, the Germans succeeded in halting the progress of the Fifth Army, but not before it had captured most of its first and second objectives. The Germans held a tactically important position on Gheluvelt Plateau, which allowed them to pour enfilading fire into Gough’s right flank. Haig issued orders that the plateau needed to be captured at all costs. The British had gained nearly 3,000 yards and captured 5,600 prisoners in their first thrust.

The situation worsened in the late afternoon when it began to rain. The rain, which would last for nearly a week, turned the terrain into a muddy quagmire. The British continued their offensive despite the harsh weather; however, Haig decided on August 4 to postpone operations indefinitely. Up to that point, the Allies had suffered 35,000 casualties and the Germans an equal number.

The Fifth Army renewed its attack a handful of times in August. It gained some ground, but at a heavy price. The weather still remained uncooperative, with more pounding rain. “The labor of bringing up supplies and ammunition, of moving or firing the guns, which had sunk up to their axles, was a fearful strain on the officers and men, even during the daily task of maintaining the battle front,” wrote Gough. “When it came to the advance of infantry for an attack, across the water-logged shell-holes, movement was so slow and so fatiguing that only the shortest advances could be contemplated.”

Disappointed in Gough’s performance and his failure to take the vital Gheluvelt Plateau, Haig had Plumer take over. Unlike Gough, who attacked on a wide front, Plumer planned to use “bite-and-hold” tactics: He would attack on a shorter front with shorter advances after a long bombardment to take the heavily defended Gheluvelt Plateau. Once this was taken, then a push on to Passchendaele Ridge could be made.

As preparations for the coming attack were underway, Haig was summoned on September 4 to meet with Lloyd George. The prime minister was displeased with the way things were progressing in the Ypres Salient. He argued that because Russia was succumbing to revolution, mutinies were occurring in the French Army, and the Americans had not yet begun arriving in large numbers, it would be better to suspend operations in Flanders. Haig, who was backed by Robertson, argued that it was for these very reasons of Allied weakness that the offensive had to continue. Haig won the argument.

The attack was scheduled for the early morning of September 20, but hours before the troops were to advance, the rains came again. At 5:40 a.m., the British guns that had been shelling the Germans for a few days now laid down a creeping barrage. Following behind the curtain of shells were the I Australian Corps, the New Zealand Corps, and the British X Corps of the Second Army attacking up the Menin Road east of Ypres. Five divisions from the Fifth Army also attacked to the north. This time, there would be little tank support.

At a cost of 20,000 casualties and an advance of 1,500 yards, the Second Army’s attacks were successful, taking its objectives and digging in. The expected German counterattacks were stopped in the afternoon by furious bombardments and spirited machine-gun fire. Plumer quickly prepared for the second stage of his offensive, aided by a clearing of the weather.

Lloyd George visited the front to find Haig beaming with victory. Told of the visible deterioration of the German prisoners, Lloyd asked to see for himself. The prime minister was shown only the sickly POWs, giving him the impression that the German army was being worn down.

At dawn on September 26, the 5th and 6th Australian divisions of the I ANZAC Corps followed a creeping barrage toward Polygon Wood on the Gheluvelt Plateau. “The advance itself was the finest we had ever experienced,” recalled Lt. Sinclair Hunt 55th Battalion of the 5th Australian Division. “The artillery barrage was so perfect, and we followed it so close, that it was simply a matter of walking into the positions and commencing to dig in.”

Attacking to the south of the Australians was the X Corps, which, with the help of an Australian brigade, captured its objectives. The expected German counterattacks were defeated. Haig had gained another 1,200 yards.

“I am of the opinion that the enemy is tottering and that a good vigorous blow might lead to decisive results,” Haig told his generals. Plans and preparations were quickly made for an attack on the eastern side of Gheluvelt Plateau and the village of Broodseinde. The Allied guns opened fire at dawn on the rainy morning of October 4. The I and II ANZAC Corps moved toward Broodseinde Ridge, while the X Corps pushed further into the Gheluvelt Plateau. Supporting them on their northern flank were elements of the Fifth Army.

By mid-day, the Australians, New Zealanders, and British had made an advance of 1,200 yards, secured their objectives, dug in and repulsed German counterattacks. Gheluvelt Plateau, Broodseinde, and the surrounding high ground had been taken at the cost of 20,000 casualties. The Second Army now found itself in front of Passchendaele.

Haig was elated with the success and planned three more hurried advances, scheduled for October 9, 12, and 14, to capture the village of Passchendaele and the ridge of the same name. Haig was certain the Germans were near their breaking point with few reserves and that now was the time to hit them hard again. Although the Germans had received heavy losses, though, they were far from finished.

The Germans again modified their defensive tactics to deal with the Second Army’s successes by creating a so-called “outpost zone” in front of their lines, lightly manned by a thin chain of positions. When the attack came, these outposts would fall back to the main line and a destructive heavy-artillery bombardment would be laid down on the advancing enemy in the outpost zone. It was hoped this would give time for the counterattacking divisions to get into position. However, what the Germans really needed to stop the Second Army was rain.

The Germans soon got their wish, as it began to rain hard on October 7. The wide swath of shell-cratered lowlands before Passchendaele Ridge was soon turned into a sea of mud. Rain would continue to fall through much of the month. Despite the weather, preparations for the coming attack continued, as engineers—hampered by enemy shelling—constructed roads to move up supplies and guns through the mud. Horses and mules carrying eight artillery shells each, struggling through the mud sometimes up to their bellies, brought ammunition to the guns; it was not enough to supply the demands of the guns that managed to be dragged forward.

Despite the conditions, less preparation time, and the reduced artillery support, two British divisions serving with the II ANZAC Corps—exhausted from getting to the start point—attacked on the morning of October 9. The attacks had only limited success, with heavy casualties. Three days later Haig tried again. The 3rd Australian and the New Zealand divisions spearheaded the attack for the II ANZAC Corps. The New Zealand division received orders to take the heavily fortified Bellevue Spur, a knoll protecting the western approach to Passchendaele. The Australians had orders to advance to the outskirts of Passchendaele.

Fierce German machine-gun fire, thick rows of barbed wire, and a sea of mud cost the New Zealanders 3,000 casualties for little gain. The 9th Brigade of the Australian 3rd Division did manage to make it to the outskirts of Passchendaele, but with no support and mounting casualties, they had to pull back. Suffering severe casualties and worn out, the ANZACs would soon be relieved. The breakthrough to Roulers and clearing the Belgian coast seemed no longer attainable, but Haig was still determined to take Passchendaele Ridge despite the appalling conditions of the battlefield. With Lloyd George still attempting to halt the campaign, Haig needed a victory to save his career, and he now turned to the Canadians Corps.

“There’s a mistake somewhere. It must be a mistake! It isn’t worth a drop of blood!” roared Lt. Gen. Sir Arthur Currie, commander of the Canadian Corps, to his staff when he got wind of a rumor that his corps would be sent to Passchendaele on October 3.

There was no mistake, as Maj. Gen. Sir Henry Horne, commander of the British First Army of which the Canadian Corps was a part, confirmed to Currie. The Canadians were to be sent to Gough’s Fifth Army. This Currie would not tolerate and told Horne plainly that he would not serve under Gough, whom he believed had mishandled the Canadians the year before on the Somme.

Haig agreed to send the Canadians to Plummer’s Second Army instead. They would still be going north to Flanders in an attempt to take Passchendaele Ridge, however, and Currie received his official orders 10 days later. On October 13, Currie went to see Plummer personally. He estimated it would cost the Canadians 16,000 casualties to take the ridge and asked Plummer “if a success would justify the sacrifice.” Plummer could only reply he had his orders.

Because of his experiences in the Ypres sector in 1915 and 1916, Currie had no desire to return to the sector. “[I] never wanted to see the place again,” he said after he received a visit from Haig. Nevertheless, he energetically set about getting his 100,000-strong corps moving north. By October 17 Currie had sent observation parties to the battlefield to reconnoiter the situation. At 9:00 p.m. every night, a conference was held to evaluate the incoming reports—and they were not good. “The mud was quite indescribable,” wrote Lt. Col. Edmund Ironside of the 4th Canadian Division. Currie went to look for himself. “The battlefield looks bad,” he wrote in his diary. “No salvage has been done and very few of the dead buried.”

The Canadians were soon moving into the front lines, taking over the positions held by the 3rd Australian Division and New Zealand Division of the II ANZAC Corps. On the right of the Canadians’ new 3,000-yard position was Ypres-Roulers Railway, while on the left-half flank of their sector was a spur of high ground running southeast through Bellevue. The Ravebeck stream, swollen now to half a mile wide in places, split their sector in two. Half the terrain in their front before Passchendaele lay in water and deep mud.

The Canadians were to take over 360 British and Australian guns, but to their dismay they found just 200 guns, with the rest having been destroyed or sunk in the mud. The Canadian Corps had no shortage of artillery, but getting it to the front—as well as supplies and drinkable water—was extremely toilsome in the deep mud. The handful of roads for trucks and trails for packs animals had to be improved upon. Overcoming the skepticism of the British officers, the Canadians obtained a sawmill and felled trees in the woods to the rear. They then cut them in planks and, working around the clock, constructed plank roads. This improved conditions somewhat. To help the infantry move through the mud and water, duckboards, or, as the Canadians called them, bathmats continued, as they had in previous part of the campaign, to be laid down.

Despite the work done, getting to the frontlines was still difficult, especially with the enemy shelling and gas attacks. In the end, the Canadians would get their guns, 587 artillery pieces all together, which over the next month would hammer the German positions with 1.4 million shells. “We never found a piece of ground for a gun platform where we did not have to fill a shell hole,” wrote Canadian gunner Philip Debney of the 32nd Battery.

The Canadians planned to take Passchendaele in three attacks with limited objectives. The first was to start on October 26. Haig scheduled the other two attacks for October 30 and November 6. FOn October 24, Canadian troops from 3rd and 4th Divisions made their way through the mud and water to their starting points. On the morning of October 26, the guns that had been pounding the Germans for the last four days began laying down a creeping barrage. Due to the impassable morass that split their sector, the Canadians were making a two-pronged assault. On the left, the 3rd Division attacked on a narrow front along with the 4th Canadian Mounted Rifles and the 43rd and 58th Battalions.

Eight minutes after the creeping barrage began, the troops moved forward in drizzling rain. Enemy machine guns opened up, stitching the 4th Canadian Mounted Rifles with lead. Many of the wounded who collapsed in the porridge-like mud drowned in it. A pill box and two nearby machine guns temporarily held up the battalion’s advance until 19-year-old Private Tommy Holmes leaped into action. Moving forward from shell hole to shell hole, he took out the machine-gun crews with well-tossed grenades. Returning to his comrades to get another grenade, he had soon taken out the pill box. For his bravery, he would be awarded the Victoria Cross. He was the first of nine Canadians to earn this medal over the next two weeks.

The 4th Canadian Mounted Rifles pushed on and captured Wolf Copse, their intermediate goal, but heavy fire from their flanks and front prevented them from pushing on to their final objective. They dug in and beat off an enemy counterattack later in the afternoon. Meanwhile, to their right, the 43rd and 58th battalions took their intermediate objective with little trouble. Then German shells began screaming down on them, and with little cover available, most of the men fell back to their starting line.

But 50 men of the 43rd Battalion had no intention of giving up the small hold they had on Bellevue Spur. Blazing away from the edges of shell holes, the small band of plucky Canadians beat back a number of German counterattacks. A company from the 52nd Battalion soon raced to their aid and arrived in time to stop another German counterattack. The small band of Canadians then attacked, taking a number of pill boxes and bagging 100 prisoners. Soon, reinforcements from the 52nd Battalion arrived, and by next morning, they had secured their intermediate objective and pushed to within about 300 yards of the Red Line Objective.

The flooded terrain caused a narrowing of the front in places. Because of this, the right prong of the attack by the 4th Division could only be led by the 46th Battalion with the 50th Battalion following in support. “We were wading in mud and falling in shell holes,” wrote Sergeant Don McKerchar of the 46th Battalion. The situation worsened when shells began landing on the advancing troops and machine-gun fire tore into them. Despite appalling casualties, the Canadians in this South Saskatchewan-raised battalion pushed on 600 yards to their objective, known as the Decline Copse. The copse straddled the Ypres-Roulers Railway. With help from the 50th Battalion, the 46th Battalion then succeeded in repulsing two enemy counterattacks.

The Germans pummeled the Canadians in the late afternoon with a heavy barrage of artillery fire. Behind this curtain of shells, the Germans attacked from three sides. The Canadians sent up flares to call in their artillery, but for some reason it was 20 minutes before their guns gave them support. The survivors of the 46th Battalion fell back, only to be met by Major John Hope and Captain William Kennedy, who rallied them. Supported by fire from the 10th Canadian Machinegun Company, Hope led the 46th Battalion back into action. The soldiers succeeded in capturing a rise near the Decline Copse.

That night, the 44th and 47th Battalions relieved the 46th Battalion—which had taken 70 percent casualties during the day’s fighting—and the 50th Battalion. The two fresh battalions launched a night attack against Decline Copse, thinking they had taken it. Come morning, they were informed by the Australians fighting on their right flank that Decline Copse was still in German hands. The Canadians quickly realized they had become confused in the dark and had captured a small wood instead of Decline Copse. The night of October 27, the Canadians rectified their mistake and took Decline Copse.

Although the Canadian Corps had not met all their objectives for their first attack, they were on slightly higher and drier terrain for their next scheduled attack on the October 30. Other Second and Fifth Army attacks supporting the Canadians had failed to gain much ground, with the exception of the Australians.

Preparations quickly started for the next assault, aided when the rain stopped for the three days leading up to the attack.

At dawn on October 30, the Canadian guns opened up, laying down a creeping barrage. The Canadian Corps objective was to secure their Red Line Objective from October 26 and then push on 700 yards to secure their Blue Line Objective for this day. Supporting them on the Corps’ right was the I ANZAC Corps and the XVIII British Corps on their left. Again attacking on the left of the Canadians Corps was the 3rd Division, whose objective was the final capture of Bellevue Spur. The Germans intended to fight desperately to keep this key position defending Passchendaele.

The 3rd Division was attacking on a three-battalion front this time, comprising the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, 49th Battalion, and 5th Canadian Mounted Rifles. Struggling through mud and water, the light infantry soon came under a storm of fire as they neared their intermediate objective, a strongpoint dubbed Duck Lodge. Suffering heavy casualties, the light infantry managed to take Duck Lodge at 7:00 a.m. They then advanced to the Blue Line, where the bombed-out village of Meetcheele was located. They succeeded in capturing the village after some brutal fighting.

In the intervening time, the 49th Battalion, which was deployed to the left of the Canadian Light Infantry, managed to capture their intermediate objective of Furst Farm. They had been hit hard by enemy artillery and small-arms fire, causing them to suffer 75 percent casualties. They dug in and were unable to advance any further.

To the 49th Battalion’s left, the 5th Canadian Mounted Rifles endured vicious machine-gun fire but captured their intermediate objective. Ignoring a wound in his thigh, the commander of the battalion, Maj. George Pearkes, ordered his men onward, sending a small detachment to capture Source Farm, where the attacking British units were only make slight progress. In the meantime, Pearkes took Vapor Farm, his Blue Line objective, which he described as “a rotten haystack.” The 5th Canadian Mounted Rifles fought off fierce counterattacks and managed to hold both farms, suffering severe casualties in the process. Overall, the 3rd Division had pushed the front line further up Bellevue Spur.

On the right flank, the 4th Division also attacked on a three-battalion front, using the 85th, 78th, and 72nd battalions. Machine-gun fire lacerated the advancing Canadians. Despite suffering heavy casualties, the 85th Battalion had secured its final, or Blue Line, Objectives by 6:35 a.m. The 78th Battalion also took its final objectives, as did the 72nd Battalion, whose goal was the key point of Crest Farm. A patrol from this battalion actually pushed into the flattened ruins of Passchendaele. Being in a vulnerable position, it wisely pulled back. German artillery pounded the Canadians digging in at their objectives for 18 hours. The Germans counterattacked during the night but were hurled back. Having advanced about another 1,000 yards, the Canadians now prepared for their attack on Passchendaele, which lay not far away.

Working around the clock, the engineers repaired plank roads and pushed them farther to the front. The mud-covered and exhausted troops of the battered 3rd and 4th Divisions were now pulled back to be replaced by the 1st and 2nd Canadian Divisions.

On the morning of November 6, the Canadian guns laid down a creeping barrage as the troops pushed ahead from their forward positions, hugging this exploding curtain of steel and death. Attacking on the left was the 1st Division, which advanced on a three-battalion front made up of the 3rd, 1st, and 2nd battalions. The 3rd Battalion by mid-morning had finally finished clearing the Bellevue Spur by taking Vine Cottage, which boasted a handful of pillboxes and machine-gun posts. Meanwhile, the 1st and 2nd Battalions’ attack went well against their Green Line Objective of the little village of Mosselmark, located north of Passchendaele. By 7:45 a.m., Mosselmark was in Canadian hands, and the two battalions were securing their objective.

stabilize the situation.

The 2nd Division, on the right flank of the Canadian Corps, attacked on a four-battalion front. The 26th, 27th, 31st, and 28th battalions followed the deafening creeping barrage toward their objective of Passchendaele itself. Quickly overcoming German resistance, the 26th Battalion took the high ground above Passchendaele. The other three battalions took out pillboxes and machine-gun emplacements as they relentlessly advanced toward the village of Passchendaele itself, which was, by now, not much more than a pile of rubble. Just before mid-morning, the Canadians rooted the Germans out of the village with bayonets and grenades. The Canadians had captured Passchendaele. To the north, a rare sight of green fields and gentle villages and farms greeted the mud-plastered Canadians.

But the fighting was not over yet. In a driving rainstorm, the Canadians launched another attack on November 10 to capture the remaining high ground north of Passchendaele. A creeping barrage opened up at 6:05 a.m., and the 7th and 8th Battalions spearheaded the attack for the 1st Division. Their objective was Vindictive Crossroads, 1,000 yards north of Passchendaele, which they captured after some hard fighting. Half a mile further north was Hill 52, the highest point on Passchendaele Ridge. It was taken early the next morning by the 10th Battalion.

Meanwhile, the 8th Battalion had captured its objective of Venture Farm as well as four enemy 77mm guns by 7:15 a.m. The 1st British Division launched supporting attacks on their left, but they were driven back by fierce German counterattacks. The result was that the Canadian 8th Battalion’s flank became exposed. With help from the 5th Battalion, the 8th Battalion was forced to plug the gap by turning back their left flank. They were still in an exposed position, and the Germans plastered the Canadians with a horrific shelling. Taking shelter in water-logged shell holes, the Canadians held on and repulsed the German counterattacks. Passchendaele was at last securely in Canadian hands.

Currie’s grim prediction that taking Passchendaele would cost his corps 16,000 casualties was close. The Canadians suffered 15,654 casualties. On the whole, the British forces, which had advanced just five miles since July 31, suffered 240,000 casualties. German losses were comparable.

The Canadians were relieved from Passchendaele on November 14. They soon would be headed back to Vimy Ridge for the winter. Canadian Private George Bell was one of the Allied soldiers who was glad to leave. “[Passchendaele was] the most awful place in the world,” he said. Thousands of other Allied and German soldiers who endured the misery of the campaign would likely have agreed with him.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments