By Brian Todd Carey

Concentrated against the beaches of Normandy on June 6, Operation Overlord landed 9 army divisions plus support troops on five beaches in anticipation of a breakout across France and toward Berlin. American forces landed on the two western beaches, Utah and Omaha, while British and Canadian troops landed farther east on beaches designated Gold, Juno, and Sword. Overall command of Allied ground forces was assigned to Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, while Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley commanded the American Twelfth Army.

Although Allied air forces controlled the skies over the 50-mile front, bombing and strafing could not silence the well-entrenched German guns, especially on Omaha Beach, where casualties numbered more than 2,300 in contrast to 197 on Utah. Farther east, British and Canadian troops met with less resistance and suffered fewer casualties than the Americans. By day’s end, close to 150,000 Allied troops and their accompanying vehicles, equipment, munitions, and provisions were unloaded. Within a week the troop buildup numbered half a million men. By June 10, the separate beachheads had been consolidated into a single front; the Americans were making ground inland and toward the city of Cherbourg on the Cotentin Peninsula. Montgomery’s forces, having beaten off panzer counterattacks, pushed toward the city of Caen. By late July, two million men and 250,000 vehicles were ashore in Normandy.

Despite the infusion of massive amounts of men and materiel, the planned Allied breakout across France bogged down in Normandy, where the thickly banked hedgerows or bocages provided the German defenders with excellent antitank positions. This slowing of Allied momentum helped the Germans reinforce Normandy with infantry divisions from the Wehrmacht’s First and Nineteenth Armies. Cherbourg surrendered to the Americans on June 27, but the British assault on Caen (Operation Epsom, June 21-July 1), despite heavy RAF bombardment, was halted by the German Army.

In an attempt to break German resistance around the city of Caen, Montgomery ordered 457 Halifax and Lancaster bombers to carpet bomb the area. The July 7 air operation against Caen dropped three thousand tons of high explosives in front of the British Army still on the outskirts of Caen. Because the bombs were mainly 1,100-pounders, they created craters 20 feet across and filled the streets of the city with the wreckage of stone buildings. The British were able to fight into the city, but were blocked from moving beyond it by craters and rubble.

On July 18 the British, this time aided by planes from the U.S. Eighth Air Force, tried carpet bombing again, this time with 1,676 heavy and 343 medium and light bombers. The goal was to blow a hole in the German defenses so that Montgomery could push 700 tanks through and onto the Falaise Plain (Operation Goodwood, July 18-20), thence to secure an opening toward Paris. But the German defenders again rode out the bombardment and stopped the British offensive, destroying half the British tanks in the process.

Meanwhile, Bradley’s Twelfth Army pushed south to the crucial crossroads town of St. Lô where the German Panzer Lehr Division blocked the Americans’ path out of the Cotentin Peninsula. With the failure of Goodwood and the tenacious stand of the Panzer Lehr Division came the real possibility that the intended Allied breakout of Normandy would never be realized.To break the stalemate on the battleground outside St. Lô, General Bradley proposed using American heavy bombers to blow the Germans out of the way. Operation Cobra was Bradley’s third attempt to escape from the constricted neck of the Cotentin Peninsula. The first attempt, begun on July 3, had been checked by the hard fighting of the enemy’s infantry along the floodline of the Douvre River. The second, begun on July 13, had after five days resulted in the capture of the crucial crossroad town of St. Lô, but at the cost of 11,000 casualties. Operation Cobra would utilize the might of the American heavy bomber fleet to assist the Twelfth Army in breaking out of the peninsula.

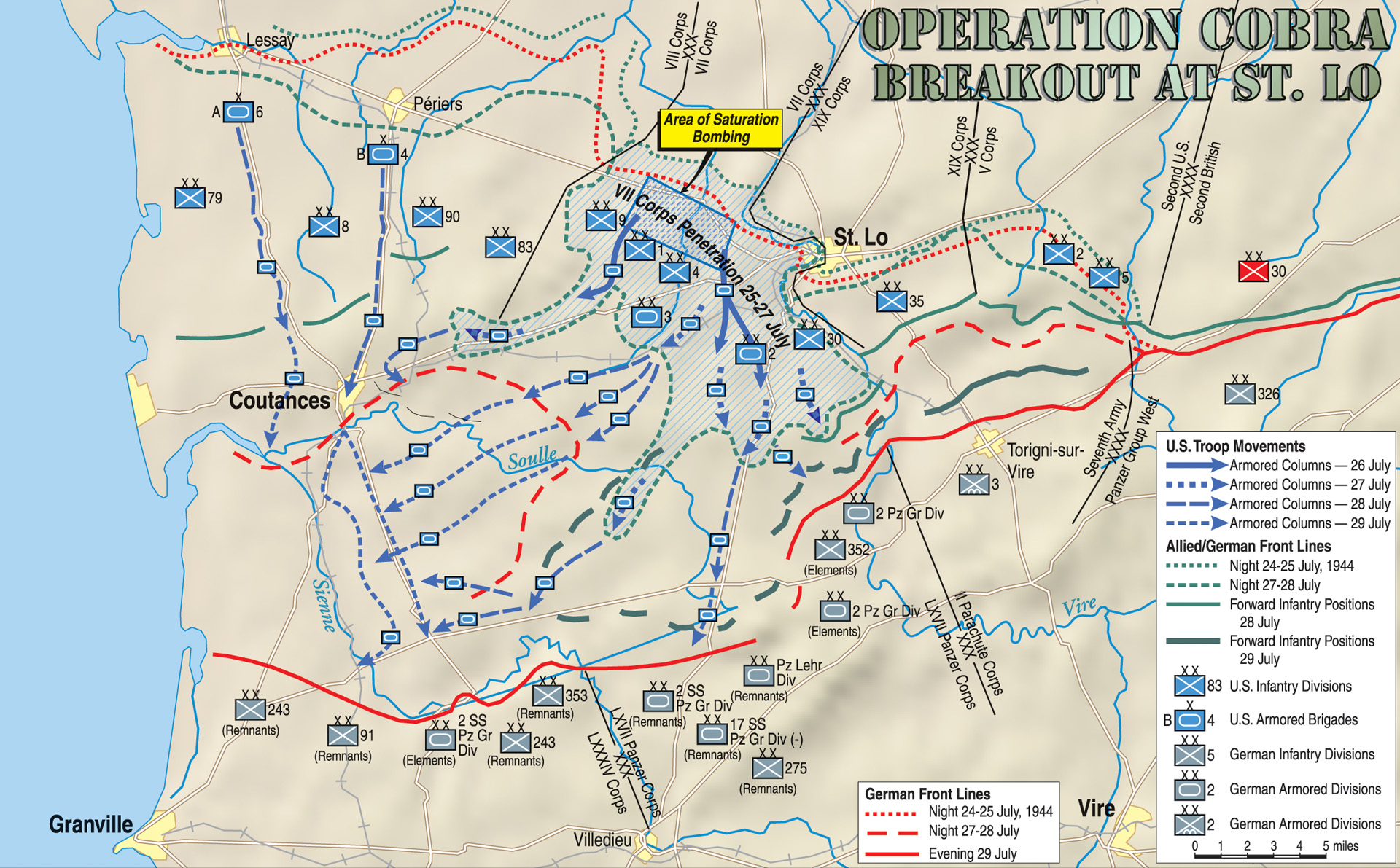

General Bradley, the chief architect of Cobra, had decided on the plan’s outline by July 10 and presented it to his corps commanders two days later. Set for July 21, Operation Cobra would carpet bomb a rectangular area approximately four miles long and 13/4 miles deep (7,000 yards by 2,500 yards), or the entire front of Bradley’s initial attack. Once the bombs had been dropped, the U.S. 2nd and 3rd Armored Divisions would punch a hole through the German defenders and finally break out of the peninsula.

Bradley understood that timing was crucial to Cobra’s success. The general wanted a short, intensive bombardment to maximize shock value. He wanted the bombers to approach the target box parallel to the front and along German lines in order to provide a greater security zone for his ground troops. He believed the bombers could attack in the morning east to west, and west to east in the afternoon, placing the sun in the eyes of German antiaircraft gunners. Immediately after the bombing stopped, the American follow-up attack had to capitalize on the shock. To best do this, Bradley planned to withdraw his troops a mere 800 yards from the front line, keeping them close enough to attack quickly and reoccupy conceded space. In order to avoid the huge craters that had slowed the British advance at Caen during Operation Epsom, Bradley required that only 100-pound fragmentation bombs be dropped.

After obtaining Montgomery’s approval, Bradley flew to England and presented his plan to Allied air commanders on July 19. In attendance were the Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder, deputy supreme commander for Overlord; Air Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory, Commander-in-Chief of Allied Expeditionary Air Force for Overlord; and Carl Spaatz, Supreme Commander of U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe. Bradley asked the men who controlled the skies over the battlefield to give him the air support he needed to break out of the Cotentin Peninsula. He was greeted in England by enthusiasm for his plan. In his memoirs, Bradley commented that “[a]ir’s enthusiasm for COBRA almost exceeded that of our own troops on the ground, for air welcomed the St. Lô carpet attack as an unrivaled opportunity to test the feasibility of saturation bombing.” He left the meeting with a commitment for 1,500 heavy bombers, almost 900 medium bombers, and some 350 fighter-bombers.

Although the Allied air commanders agreed to the plan for Cobra, they wanted some modifications. The airmen initially wanted a safety zone of 3,000 yards, compared to Bradley’s 800. Bradley finally agreed to 1,200 yards, but the heavy bombers would not strike the front edge of the target box. Instead, fighter-bombers would cover this 250 yards. More important, Bradley assumed his desire for the bombers to fly a parallel run along the German front had been accepted by all participants of the meeting. This assumption would prove to be wrong.

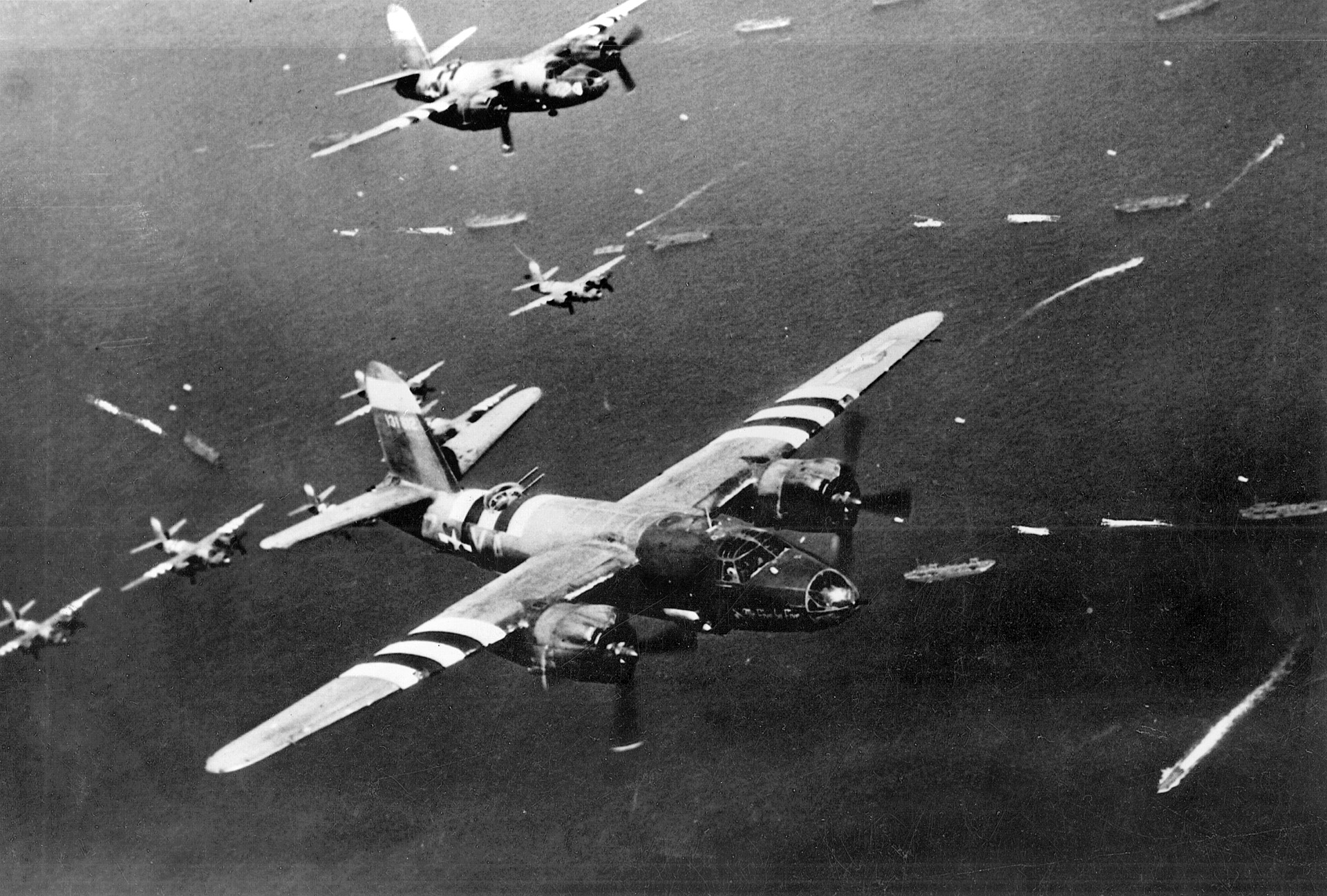

Bad weather forced the postponement of Operation Cobra from July 21 to the 24th. Although the weather on the morning of the 24th proved dubious as well, Leigh-Mallory ordered 1,586 B-17s and B-24s from the Eighth Air Force to support Cobra. Leigh-Mallory himself and other senior airmen flew to Normandy and, after seeing firsthand a 5,000-foot ceiling over the target box, called off the mission and rescheduled it for the next day. But Leigh-Mallory had waited too long to cancel the mission. With bombers only seven minutes from target, calling back all of the airplanes would be impossible. In all, 352 heavy bombers loosed their loads over the target box before finally receiving the recall order. And contrary to Bradley’s wishes, all the bombers had dropped their loads perpendicular to the front line. Some bombs fell short of their target and on the American 30th Division. Friendly fire killed 25 men and wounded another 131. Moreover, confusion caused by the cancellation of the air phase of Cobra forced Bradley’s men to fight again for the ground conceded as a safety zone.

The confusion and tragedy of the July 24 strike can be blamed on many factors. Direct communications between the bombers and the ground troops was nonexistent. Although Leigh-Mallory was physically at Bradley’s headquarters near the front, his cancellation order had to be sent back to the Eighth Air Force’s Headquarters in England, then sent to Eighth Air Force planes approaching the target area, delaying the execution of his order. Also, Bradley’s emphasis on the shock effect of the bombing at the July 19 meeting led Eighth Air Force Headquarters to instruct their planes to bomb at a right angle to the front, thereby ensuring the greatest number of bombers through the short side of the target box in the least amount of time. The perpendicular strike increased the likelihood of friendly-fire casualties, but it also saturated the breakthrough point with bombs in the way Bradley required. Given the choice between a safer, lengthier attack or decreasing the shock value of the carpet bombing, Bradley reluctantly agreed to another perpendicular strike.

The air phase of Operation Cobra began at 10 a.m. on the morning of the 25th. Some 1,503 of 1,581 B-17s and B-24s dropped their high explosive and fragmentation bombs on the Panzer Lehr Division. Joining the Eighth Air Force’s heavies were medium bombers and fighter-bombers. All to-gether, the air effort dropped over 4,100 tons on German positions, killing over a thousand German soldiers, wiping out three battalion command posts, and destroying or severely damaging most of its armor and armored personnel carriers.

The effect of the bombing on the already understrength Panzer Lehr Division was significant. The German division commander, Lt. Gen. Fritz Bayerlein, described the scene outside of St. Lô in a postwar interrogation: “It was hell…. The planes kept coming overhead like a conveyer belt, and the bomb carpets came down…. My front lines looked like a landscape of the moon, and at least seventy percent of personnel were out of action—dead, wounded, crazed, or numb.” Bayerlein placed the actual losses of dead and wounded at approximately 50 percent by bombing, 30 percent by artillery, and 20 percent by other weapons.

Still, despite the devastating pattern bombing and the artillery barrage that followed, the Americans were unable to break through the German lines on the 25th. But the American commander opposite the most battered part of the Panzer Lehr Division’s lines, Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins, shrewdly realized that the German command and control structure had been badly disrupted by the air attack, and planned a full-scale attack the next morning. On the evening of the 25th, Collins brought his VII Corps armor, newly equipped with iron shears to bulldoze the hedgerows, to the front with orders to push through the remaining German defenders at dawn. In the morning the 2nd Armored Division, supported by tactical air and building on the accomplishments of the 30th Infantry Division, cut through the demoralized German defenders. Breakthrough had become breakout, and the race to Germany had begun.

The July 26 breakthrough at St. Lô owed its success to aggressive pattern bombing the previous day. Bradley’s use of heavy bombers in close air support of ground operations brought the weight of American airpower to bear against a vulnerable opponent at an opportune time. But the success of Operation Cobra was tainted by more friendly-fire incidents. Once again, American bombs accidentally hit units in the 30th and 9th Infantry Divisions.

In all, short bombs killed 111 Americans, including Lt. Gen. Leslie J. McNair who had come to Europe to assume command of the newly forming American Ninth Army, and wounded 490 more. Moreover, the close proximity of American troops to the intensive bombing caused 164 post-traumatic shock cases in the 30th Infantry Division, further reducing their combat efficiency.

High-level finger pointing took place as a result of the friendly-fire deaths. General Spaatz tried to place blame on the medium bombers of IX Bomber Command. The Eighth Air Force’s own investigation showed the 2nd Air Division was responsible. In his memoirs, General Bradley accused the airmen of “duplicity,” claiming they had told him the July 25 bombing would be parallel to the road. But Bradley and other ground commanders’ failure to pull their troops back from what was known as a very dangerous front raises their culpability. What is certain is that the blame for the short bombings does not rest entirely on any one service. Although there was no “duplicity” on the part of the Army Air Force (in fact, air commanders were reluctant to undertake the operation at all), airmen from Tedder and Leigh-Mallory to the bombardiers themselves deserve some of the blame.

Mk IV panzer, an American infantry patrol picks its way through the rubble of a Normandy village, wrecked during the Operation Cobra bombings. Cobra was launched to break through the second line of

German defenses and regain the momentum lost after the initial Operation Overlord landings.

Despite the demoralizing effect close air support had on friendly troops, American ground forces successfully pushed through the battered German defenders. The success of Cobra owed to many factors. Unlike Montgomery’s failure in Operation Epsom a month before, Bradley attacked with a much greater force against a critically weaker enemy. The German forces in Normandy had suffered seven weeks of attrition and were split between defending the strategic crossroads at St. Lô and the defense of Caen. Unable to reinforce either sector rapidly due to Allied air interdiction, short of ammunition and without Luftwaffe air support, the German line of defense was vulnerable to puncture.

Both Montgomery and Bradley recognized the utility of using heavy bombers in support of ground troops, but the failure of Allied heavy bombers to break the back of German resistance at Caen (causing considerable collateral damage to French civilian and friendly troops) did not deter Bradley from using them at St. Lô. Although friendly-fire casualties did occur in both operations, it was a relatively small price to pay considering the overall stakes. In July 1944, the breakout of Normandy had stalled, and without a determined Allied combined-arms offensive the very existence of a Second Front was endangered.

Operation Cobra vividly illustrated the firepower heavy bombers could bring in support of ground troops. Although an inexact science in the summer of 1944, the close air support operations in Normandy were the precursor to heavy bombers being used in later ground support missions in the European Theatre and later in Korea, Vietnam, and the recent Gulf War. Heavy bombers have proved a powerful addition to the arsenal of ground commanders, providing critical offensive mass at crucial moments.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments