By Dr. Richard Selcer

As Soviet armies threatened Berlin in February 1945, Nazi Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels promised the German people that the capital would be defended to the last stone and the last man. “We cannot let Königsberg put us to shame,” he declared, comparing Berlin to the capital of East Prussia, at the time surrounded and desperately holding out against the Red Army.

Königsberg would hold out until April 9, 1945, three weeks before Berlin fell. What Goebbels and his master, Adolf Hitler, never knew was that 450,000 German civilians and wounded soldiers had managed to escape from the Königsberg pocket, thanks to the extraordinary efforts of the Kriegsmarine—the German Navy.

The last great German military operation of World War II was not the Ardennes offensive of December 1944 but Operation Hannibal on the shore of the Baltic Sea, from January into May 1945. Operation Hannibal was a seaborne evacuation on a scale that put the British evacuation of Dunkirk to shame. It has been largely forgotten because it was a strictly naval operation and contravened Hitler’s explicit orders.

Mass evacuations are born of the sort of desperation where flight takes precedence over fight. They do not go down in history because they mean defeat. It took a unique British spin to turn Dunkirk from the disaster it was into a triumph of British pluck. Germany was able to duplicate that feat in the final months of World War II and even top the “Miracle of Dunkirk” by bringing out five or six times as many people.

In the fall of 1944, the German army was in full retreat in Eastern Europe between the Baltic and the Danube. From the heady days of 1941, when German forces swept through Poland and the Soviet Union driving everything before them, the Wehrmacht was now back on its heels.

The turnaround began with the Battle of Kursk (July 5-August 23, 1943), with the German forces suffering irreplaceable losses. The three German army groups that had begun the invasion of Russia (North, Center, and South) were bled white. Army Group North waged a fighting retreat from Leningrad south through Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Army Group Center was charged with shielding East Prussia, wedged between Belarus and the Polish Corridor.

The stage for German defeat was set in June 1944, when Moscow launched Operation Bagration to coincide with the opening of the Western Front in France. It pushed the Germans back from Leningrad all the way to Latvia and liberated Belarus. By August it had obliterated Army Group Center, cut off Army Group North, and was driving toward the Baltic.

The Germans retreated into a defensive pocket on the Courland Peninsula (Latvia), where 200,000 Germans and Latvians, 33 divisions in all, fought with their backs to the sea against 1.7 million Soviet troops. By October, they were surrounded and cut off from all resupply except by sea.

Not even the Luftwaffe could help the army, as it was concentrated in the west to defend against the British and American bombing campaign. In January, Hitler ordered the remnants of Army Group North rebranded as Army Group Courland.

It was not just Hitler’s suicidal obsession with not surrendering a single meter of German soil that lay behind the orders to hold the eastern Baltic. The new Type XXI U-boat was undergoing sea trials there. The new-and-improved U-boats, like the V-1 and V-2 rockets, were the last forlorn hopes to save the Thousand Year Reich.

Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz was as interested in putting the new U-boats into operation as Hitler, not because he clung to any hope of winning the war but in the hope of persuading the Allies to negotiate a more favorable peace.

Hitler’s standing orders on the Eastern Front were “no surrender, no retreat.” He insisted on a strategy of Feste Plätze, which meant holding “fortified places” like the Courland peninsula and the cities of Kolberg (Kolobrzeg, Poland), Königsberg (Kaliningrad, Russia), and Danzig (Gdansk, Poland) at all costs. He believed it would cost the Red Army more to take these places than it would the Germans to hold them.

Also known as the “wave-breaker” strategy, this produced a series of encirclements and precipitous retreats in late 1944 that so infuriated Hitler that in January 1945 he issued orders that no troop movements whatsoever be initiated without his personal approval. This meant no withdrawal to more defensible lines. It also meant, as the Red Army raced across Poland covering a hundred miles in little more than a week, that the sea was the German defenders’ last lifeline.

East Prussia became a death trap for tens of thousands of Germans. Masses of civilians joined broken military units fleeing to the west. Those who made it across the Oder River swelled the refugee population of Germans already evacuated from bombed-out cities in the western Reich. Secret pre-war plans had called for a “phased evacuation” of East Prussia in the face of overwhelming attack until a counterattack could be organized; Hitler’s orders put an end to those optimistic plans, and instead, every German who could flee westward did so, terrified of being caught by the Red Army.

By early 1945, Germany controlled only a narrow land corridor some 50 miles wide stretching along the Baltic coast from Königsberg to Swinemünde. It was under constant attack from the air and would be completely cut off by the Russian army in March. Long before then, the best escape route was not overland but by ship to safe ports.

Control of the Baltic was crucial to mass evacuations. It had been a “German lake” at the beginning of the war. Kiel was the home port of a large part of the German fleet. However, by 1944 things had changed—RAF bombers and Soviet submarines were making operations risky.

In 1944, the Kriegsmarine got practice shuttling transports up and down the coast when it evacuated British and American POWs from stalags (POW camps) in Poland and East Prussia. Most POWs had to march overland, but some were transported in the holds of ships. They ironically dubbed their trips “Baltic cruises.”

The Kriegsmarine itself had very little to do with these evacuations, only providing escort. Still, those evacuations served as a blueprint for the wholesale evacuation of Germans a few months later. Thus, Baltic ports were not just defensive citadels; they were havens for fleeing Germans.

Danzig, at the mouth of the Polish Corridor, was one of those strongpoints blocking the Russian advance into the German heartland. With its deep-water port of Gotenhafen 20 miles away, it formed a single defensive citadel. The Poles had turned Gotenhafen into the largest and most modern port on the Baltic even before Germany seized it in 1939. The Germans had turned it into a major naval base, an extension of Kiel’s Deutsche Werke shipyard, whose drydock and heavy cranes were capable of servicing the largest warships.

At the end of 1940, the battleship Scharnhorst went there for repairs, and in April 1942 Scharnhorst’s sister ship Gneisenau came to Gotenhafen to be decommissioned on Hitler’s orders. Her gun turrets were removed and repurposed as shore batteries.

Gotenhafen was home port for several units of the Kriegsmarine, and, unrelated to its naval activities, was a subcamp of the Stutthof concentration camp, holding thousands of Poles, Russians, and others. Their presence was another reason to keep Danzig-Gotenhafen from falling into Russian hands. The initial Russian offensive would bypass Danzig-Gotenhafen in January 1945; it only became a focus of the Red Army in March 1945, when Marshal Kinstantin Rokossovsky was ordered to take it.

Across the Gulf of Danzig was Königsberg, another German strongpoint, designated an “invincible bastion of German spirit” by Hitler himself. It lay on the north end of the Vistula Lagoon and served as the gateway to the Königsberg peninsula. On the same peninsula was Pillau (now Russian Baltiysk), one of Germany’s last U-boat training bases and a vital port for resupplying Königsberg.

On August 26, 1944, RAF bombers hit Königsberg for the first time, bringing the war home to people who to this point had heard nothing but Nazi propaganda about how Germany was winning the war. Those who could, fled the city in panic, mixing with retreating German army units in a chaotic mass of humanity.

In October 1944, Königsberg was completely cut off by the Red Army, leaving 130,000 German defenders bottled up inside. From that point on, the only way in or out was by sea—either from its own harbor facilities or through Pillau.

The last German strongpoint on the coast was Kolberg, transformed into a defensive bastion even as 70,000 civilian refugees poured into the city. The German Army High Command (OKH) hoped to keep Kolberg open as a supply port for forces farther east while bleeding the Russian army white at the gates.

What Hitler saw as “fortified places” to wreck the onrushing Russian juggernaut were in reality death traps. They were defended by forces that existed mostly on paper, like the impressive-sounding 4th, 16th, and 18th Armies, which were actually a grab-bag of SS, Wehrmacht, and home-guard units possessing few tanks or heavy weapons. German civilians trapped in these pockets with the defenders faced three distasteful options: stick it out and hope their defenders could keep them safe, surrender to the Red Army, or try to get aboard an evacuation ship.

Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz held the key to the fate of Baltic Germans. Appointed Supreme Commander of the Kriegsmarine by Hitler in 1943, he also assumed command of what was left of the German merchant marine. He lost most of his capital ships in January when Hitler, in a fit of pique, ordered them decommissioned and their crews transferred to land defenses and submarine duty.

Dönitz managed to save most of his ships from the scrap pile, but keeping them at sea was a different matter. The idea for Operation Hannibal came to him in late 1944 or early 1945. He was supposed to keep supply lines open to the Baltic strongholds and carry off the wounded. But why bring back transports half empty when there were thousands of German refugees begging to be evacuated?

With most of his surface fleet tied up at the docks, he was forced to assemble a makeshift flotilla to mount a sea-borne evacuation of massive scope. To man his fleet, he would have to make do with the skeleton crews he still had at his command, augmented by the wharf rats he could scrape together in German-held ports.

The Kriegsmarine of 1945 was still impressive, on paper at least. Capital ships included the heavy cruisers (dubbed “pocket battleships” by the British) Lützow (formerly Deutschland), Admiral Hipper, Admiral Scheer, and Prinz Eugen.

The Lützow had gone to Kiel at the end of 1943 for a complete overhaul before getting a second life in Baltic operations. The Admiral Hipper went there in 1944 to put her beyond the reach of RAF bombers. Like the other capital ships, she had been decommissioned on Hitler’s orders, but Dönitz returned her to service in the summer of 1944, moving her to Gotenhafen, a more secure port. Most of her crew was subsequently drafted into the defenses of Danzig. In January 1945, she was ordered back to Kiel, where she was sunk at her moorings in April.

The sister ships Prinz Eugen and Lützow of the Admiral Hipper class would prove to be the most effective in Baltic operations in the last months of the war, serving in both fire-support and escort-duty service almost to the end.

Other warships at Dönitz’s disposal for his Baltic operations were the light cruisers Köln and Leipzig and the antiquated battleship Schlesien. They were supported by the Sixth Destroyer flotilla and a handful of torpedo boats. Half of Dönitz’s challenge was keeping them in operating condition. Mechanical problems, shortages of fuel and ammunition, and depleted crews made implementing Operation Hannibal all the harder.

Fortunately, the Soviet Red Banner Fleet remained in port late in the war even after most of the German Baltic fleet was confined to port. This has led one modern scholar to speculate that Stalin planned to depopulate East Prussia in the first organized ethnic cleansing in modern history by letting its German population flee to the west of its own volition.

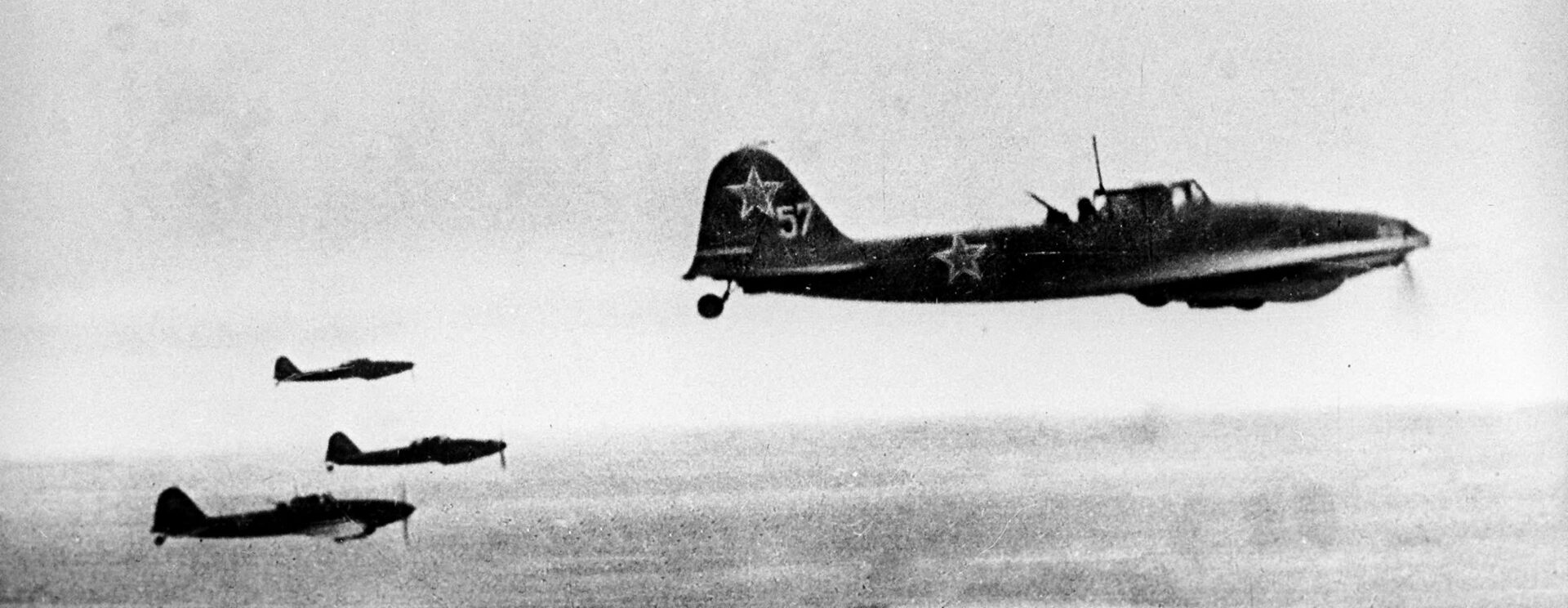

According to this theory, such a strategy had the added benefit of burdening the rump Reich with refugees. However, the Red Air Force spurred them on their way, ranging at will in the skies over Courland, Königsberg, and other areas of German resistance.

In early January, Hitler granted permission for a partial withdrawal from the Courland pocket. Dönitz’s little crackerjack fleet pulled out the 4th Panzer Division, 31st, 32nd, and 93rd Infantry Divisions, 11th SS Division “Norland,” remnants of 227th, 218th, and 389th Infantry Divisions, and the 15th Latvian SS Division. This still left nearly 120,000 men trapped in the pocket, ordered to hold down the Russian army, and Dönitz still had to keep them supplied and bring out the most severely wounded.

While German officers like Generalobersts Ferdinand Schörner and Lothar Rendulic dutifully held their positions on the Baltic front, Dönitz defied the Führer’s “no retreat, no surrender” orders.

Dönitz was the rare German officer who refused to follow Hitler’s headlong rush to annihilation. Operation Hannibal was implemented on his initiative alone to evacuate military personnel in addition to as much of the desperate German population of East Prussia as he could save.

Word did not get back to Berlin because high-ranking Nazi officials caught behind the lines were as desperate as any civilian to hitch a ride to safety on one of Dönitz’s evacuation ships; they were not about to report him.

And Dönitz himself had a ready defense for his actions. Writing in his memoirs years later, he insisted that his purpose was never to capitulate but to fight on, “evacuating as many [Germans] as possible away from the Soviets.”

Another objective was to save the last two U-boat training bases. At this point in the war, the precious submarine fleet was the only branch of the Kriegsmarine still conducting offensive operations. If called to account, Dönitz could argue that Operation Hannibal aimed to save those U-boat training divisions stranded in the Baltic that were going to could turn the war around even now. The Grand Admiral’s priorities were to first bring out naval personnel, then sick and injured fighting men, and finally high-ranking military and civilian personnel. Any ordinary Germans able to hitch a ride were a bonus.

The Baltic ports capable of handling large ships and masses of people were Gotenhafen, Pillau (tip of the Samland peninsula), and Swinemünde (on the Oder-Neisse estuary), but even those were not truly safe. Swinemünde came under RAF bombardment in 1945, and the land link between Königsberg and Pillau was so vulnerable to Russian bombardment that civilians were forced to flee across the frozen Vistula Lagoon on foot.

Also driving Dönitz’s actions was the unlikely hope that Germany could find common cause with the Western allies against the Soviet Union. The more personnel Dönitz could save from destruction, the more attractive such a proposal might be to SHAEF (Western high command). At the very least, they could make a final stand on German soil. But first, he had to get them out of East Prussia and Poland.

He put Generaladmiral Oskar Kummetz and Admiral Konrad Engelhardt in charge of Operation Hannibal. Their pairing and their ranks are an indication of the high priority Dönitz put on the operation, and he issued the formal orders on January 23, 1945.

Kummetz and Engelhardt rounded up between 600 and 1,000 vessels—including pleasure craft, fishing trawlers, ferry boats, landing craft, freighters, and passenger liners. This fleet staged in Gotenhafen, Pillau, and Swinemünde. Over the course of the next 15 weeks, they brought off some 350,000 military and naval personnel, plus 800,00 to 900,000 civilian refugees, including high party officials, medical personnel, and the families of a few fortunate soldiers.

Often compared to the “Miracle of Dunkirk,” which saved 338,000 British and French military personnel, there were other differences besides the numbers. Operation Hannibal had no air cover, which the RAF had provided at Dunkirk. Also, the fleeing Germans did not try to bring their equipment away with them. This was strictly a human evacuation.

Furthermore, large numbers of German evacuees were civilians who could contribute nothing to carrying on the German war effort. The high command euphemistically called the civilian evacuees “compatriots” to avoid using the word “refugee,” with all its demoralizing connotations.

Regardless of the terminology, there was no denying the numbers brought home. By Dönitz’s estimation, Operation Hannibal saved more than two million German lives.

The refugees were dropped off at several ports and fishing villages on Germany’s Pomeranian coast: Swinemünde, Sassnitz (Rügen Island), Rostock and Warnenemünde (Bay of Mecklenburg), Stolpmünde and Rügenwalde. These places were out of the path of the Soviet army but in no way prepared to receive thousands of refugees. Due to the hasty and secretive nature of the operation, the locals were unprepared to either feed or house the refugees dropped in their laps.

The supposed safety of these destinations proved short-lived, in any case, because they did not have defensive garrisons or anti-aircraft defenses. This merely prolonged the agony of many evacuees, who had believed they were now safe.

Other drop-off places could not even be dignified by calling them ports; they were dots on the map, with names like Horst, Dievenow, and Wollin (the name for both the town and the island it was on).

Readying and loading the evacuation ships was mixture of desperation and determination. German port authorities tried to send the ships off in convoy for their own protection, but this delayed outbound trips and made them vulnerable to Russian air attacks in port.

On any given voyage, the number of people trying to board the outgoing vessels far exceeded the available space. Fear made people frantic, causing them to rush the gangways or try to sneak aboard unnoticed. Who knew when another convoy would sail, or even if there would be another?

The authorities tried to implement a system of passes, but papers were easily forged, and the guards were not especially diligent. Officially, priority went to submariners who were considered “essential personnel” and to Nazi officials (with their families). They went to the head of the line.

The first evacuation ship out of Pillau sailed on January 28, carrying 1,800 civilians and 1,200 badly injured military casualties. The ship slipped out of port without escort under cover of darkness to avoid air attacks and reached safety the next day. Back in the Königsberg pocket, the German defenders fought to keep the lifeline to Pillau open because it was their last hope of escape.

On February 9, a German counterattack by elements of the 3rd Panzer Army and 4th Infantry, led by a captured T-34, reopened the route from Königsberg to Pillau. The Germans managed to keep it open until April, allowing supplies to come in to the defenders and casualties and refugees to be evacuated. The Soviets focused their attentions on smashing the defenders, content to let the sick and wounded flee back to Germany. Surviving soldiers would be in no condition to fight again, and the refugees would be an added burden on a collapsing German economy.

Some German civilians got on the evacuation list because of their previous sacrifice for the Reich. The pastor of a small East Prussian village church and his wife got a pair of passes because they had given two sons to the army. But first they had to get to Gotenhafen, which meant joining a stream of refugees on the icy roads going west. They took whatever personal belongings they could carry with them. The pastor made it and was taken on board the Wilhelm Gustloff, but his wife died along the way, to be hurriedly buried on the side of the road. He told a crew member of the Wilhelm Gustloff, “Everywhere we looked there was only suffering and despair.”

The pastor’s journey to hell was not over yet. He was on board the Wilhelm Gustloff when it was torpedoed and went down. He was one of the few survivors.

Luftwaffe Captain Franz Huber was one of the fortunate wounded German soldiers whose injuries were serious enough to get him a ticket home without being fatal. He was scheduled for evacuation on February 9 from Pillau. Arriving at the port, he was loaded aboard the General von Steuben, along with other wounded Luftwaffe and Wehrmacht officers, headed for Swine-münde and a German military hospital.

They were all under the impression they would have safe passage aboard an official hospital ship, although not a single Operation Hannibal transport had the distinctive Red Cross painted on it. There was no time, nor any guarantee the Russians would have respected it.

Space was limited even on the available passenger liners because of the harsh winter weather. Refugees could not be left on open decks for the entire voyage. Military personnel and Nazi officials got the cabins and staterooms. Civilians were placed in steerage class and passageways. Still, some managed to stow away out of sight on the upper decks, desperate enough to take their chances with the weather. No one complained about their accommodations.

Other issues came up that were a product of the desperate times. Large passenger liners like the Wilhelm Gustloff and the General von Steuben were supposed to carry a full complement of lifeboats, but those had been taken for other purposes at this stage of the war, and there was no time to find replacements.

Life jackets, which should have been issued to all passengers and crew, were also in short supply. That did not matter much, because anyone plunged into the icy waters of the Baltic would die of hypothermia in a matter of minutes.

Then there was the matter of fueling and making sea-worthy the rust-buckets that had sat at anchor for months. The Wilhelm Gustloff, for instance, had not put to sea for four years. During that time, it had been used as a training barracks for submarine crews.

Soviet aircraft did not make things any easier. Not having to tangle with the Luftwaffe, they strafed oil tanks and refugees crowded onto the wharves. German antiaircraft fire was limited by a shortage of guns and ammunition.

Even the idea of sending the evacuation ships in convoy proved to be wishful thinking; the Kriegsmarine did not have sufficient escort vessels to protect the ships. The only warships available were the handful of destroyers, minesweepers, and torpedo boats still operable. The surviving German cruisers were either holed up in port or providing fire support for besieged strongpoints like the Courland pocket.

Ironically, arming the evacuation ships with a few deck guns would have offered no practical protection, but it would have removed any claim they might have had to protected status as either hospital ships or civilian liners.

The operational plan of Hannibal was for the evacuation ships and any escorts they could muster to make a dash for their destination under cover of darkness, sticking close to the coastline to avoid Soviet airstrikes standing out against the night sky. It was a flawed plan, though, because while a dark, overcast sky might hide them from aerial attack, it could not protect them if a Soviet submarine caught sight of them.

Nor could darkness offer any protection against the mines both sides had liberally seeded the sea routes with. Every voyage was a roll of the dice but still preferable to setting out overland with all the horrors that held. Everyone had heard the stories of slaughter and rape being perpetrated by the Red Army. And if the Red Army did not get them, they faced death from exposure or starvation.

Operation Hannibal was fortunate that the Soviet surface fleet did not come out to challenge it. But Soviet submarines were not so passive. Several refugee ships were torpedoed and went down, with little hope of rescue ships showing up. The waters were icy cold, and many passengers were weak from hunger or wounds. Once they went into the water, they survived only a few moments even if they had on lifejackets.

There was also the fact that potential rescue vessels were reluctant to help because they, too, were afraid of being torpedoed. The doomed voyages of the Wilhelm Gustloff and Hansa were examples of everything that could go wrong going wrong.

The two vessels left Gotenhafen for Kiel carrying more than 9,000 passengers on the night of January 30, 1945, with a token escort. Not far from the harbor, the Hansa broke down and had to limp back to port, while the Wilhelm Gustloff pressed on in the darkness.

A few hours into her journey, Soviet submarine S-13 sent her to the bottom, killing more than 7,000 people, making this the worst maritime disaster in history.

The Wilhelm Gustloff was the worst, but hardly the only, loss during Operation Hannibal. On February 9, the General von Steuben left Pillau for Kolberg with more than 3,000 aboard. It, too, was caught by S-13 and sunk. Three hundred survivors were picked up by its torpedo-boat escort and carried on to Kolberg.

On February 22, the Göttingen left Courland carrying 5,000 wounded soldiers who thought they were on their way home. On their second day out, they were torpedoed, killing 2,000 of those on board. On March 7, the Hamburg hit a mine field off Sassnitz and sank. In a rare stroke of good luck, it had already unloaded its passengers. Still, the loss of the 21,600-ton liner was a cruel blow to the evacuation.

One by one, the Baltic evacuation ports fell: Kolberg on March 18, 1945; Gotenhafen on March 26; Danzig on March 30; Königsberg on April 9; Pillau on April 25; the Courland pocket on May 12, 1945.

The Red Army showed their populations no mercy. Kolberg was cut off in February and, even as it girded itself for a fight to the death, it remained a destination for refugees from farther east. It became a Russian target because it was the major supply port for German forces at Gotenhafen, Danzig, Königsberg, and Courland. Its defenders held out for a month with the help of artillery fire from the Lützow and Admiral Scheer while Operation Hannibal carried off as many as possible.

The best estimate of how many got out of Kolberg is 40,000 military personnel and 70,000 civilians. Two thousand troops remained behind on March 17 and 18 to cover the last departing transports. Eighty percent of the city was destroyed by that time, and Germans who couldn’t escape were expelled or killed.

The Russian 70th Army reached the sea on March 22, cutting the Danzig-Gotenhafen pocket in two. When Gotenhafen fell four days later, survivors retreated first to Danzig, then to the headland at Oxhöft, where they prepared for a last stand with their backs to the sea.

Königsberg was still in German hands in April, though by that time it was hundreds of miles behind the lines. It owed its survival that long to Admiral Dönitz’s lifeline. Whenever ships brought in supplies and reinforcements, they took out military and civilian evacuees.

The last four days of combat (April 5-9) was the same kind of house-to-house fighting seen in Berlin and Budapest. By that time, Königsberg’s defenders were no longer in contact with Berlin. They only kept fighting because they had been ordered to hold out.

Even as German ports fell one by one, Operation Hannibal struggled on, saving those who could get to the coast, including what was left of an army corps of mostly panzer units that had fought their way to the coast and established a bridgehead near Hoff and Horst. From there, they moved on to Dievenow, where evacuation ships picked them up on March 11 and 12 and carried them to the island of Wollin (between the Bay of Pomerania and Stettin Lagoon).

Days later, a powerful flotilla organized around the heavy cruisers Lützow and Admiral Scheer, with three destroyers and a torpedo boat as escorts, brought off another 70,000 from Wollin.

Evacuation ships were still coming and going from Stolpmünde, Rugenwalde, and Kolberg in mid-March. They brought off 18,300 safely from Stolpmünde and another 4,300 from Rugenwalde before the Red Army overran those places.

After the Lützow and Admiral Scheer were withdrawn to Kiel for safety, the evacuation fleet continued to run the gauntlet without their comforting presence in the area. On the night of April 4-5, small boats and landing craft brought off 30,000 soldiers and civilians from Oxhöft and dropped them off on Hela, the 35-mile-long sandbar (peninsula) between the Gulf of Danzig and the Bay of Puck. The Germans camped out on the beach and dug in, enduring continuous Soviet air attacks.

Hela turned out to be just a temporary stop. The evacuation fleet carried Germans off the beaches until May 10. Not all made it to safety. On April 15, a convoy of four liners and other transports left Hela with more than 20,000 refugees. The next day, Soviet submarines lying in wait pounced, sending the liner Goya, with more than 6,000 persons on board, to the bottom; only 183 survivors were pulled from the water.

In the first week of May, the evacuation brought more than 150,000 away from Hela. Some sources put the total number brought out of the Danzig-Gotenhafen pocket at 900,000. There is no way to tell for sure, because there were no records kept. Undoubtedly, many thousands were left behind.

The RAF did its part to make life hell for evacuees and for the towns that received them. On March 6, RAF bombers hit Sassnitz, the fishing village that was the final destination for many refugees. Now those refugees were caught in the open and pummeled for no good military reason. Six days later, German ships delivered 2,000 refugees to Swindmünde. They were no sooner ashore than they were hit by 671 U.S. Army Air Force bombers acting on the request of Soviet authorities. Nearly 600 died on the beaches, and six evacuation ships were sunk. Estimates of total casualties range from 5,000 to 23,000, making the raid on Swinemünde one of the “10 most destructive” bombing raids of World War II.

Operation Hannibal continued right to the end of the war and beyond. After Hitler committed suicide on April 30, Dönitz succeeded him as Führer. In a public address on May 1, the admiral vowed that the German army would “continue the struggle against Bolshevism until the fighting troops and the hundreds of thousands of families in Eastern Germany [italics added] have been preserved from destruction.”

He was still trying to negotiate a separate surrender with the West when Eisenhower informed his representatives that he had 48 hours (May 7-8) before the unconditional surrender terms would be imposed unilaterally, thereby severing the Russian sector from the West. When Dönitz realized there was not going to be any detent with the Western allies, he shifted to trying to surrender as many German troops as possible to the Brits and Americans rather than the Russians.

Even in the last 48 hours of Eisenhower’s ultimatum, Dönitz kept Operation Hannibal going. It is estimated that in the last several weeks of the war, when, for all practical purposes, the Kriegsmarine had ceased to exist, Operation Hannibal managed to carry 265,000 Germans caught behind the surrender lines to safety.

Operation Hannibal was still going on, in defiance of surrender terms, even after Germany’s capitulation on May 8, 1945. Unarmed coastal craft continued to steam up and down the Baltic coast, picking up frantic groups of refugees and carrying them beyond the reach of the Red Army. There were still a few ports inside German borders where refugees could be dropped off. What happened to them after that was up to fate.

On the very last day of the war, as Dönitz formally surrendered the Third Reich, a flotilla of 92 vessels left the Latvian port of Libau (Liepāja), part of the Courland pocket, saving 18,000 soldiers and civilians from Soviet clutches. Or not. Russian motor torpedo boats pursued the little group and forced the slowest ships to heave to so they could be boarded. Their passengers went into captivity, where those who did not die remained for years to come.

By the end, Dönitz’s mass evacuation was no longer an organized operation. It simply kept going on its own momentum until it ran out of gas, figuratively and literally speaking. With no warships and no command and control, the Kriegsmarine ceased its humanitarian mission when the news of the official surrender finally reached the last holdouts of the Reich. Left in the lurch were an estimated 180,000 German troops still in the Baltic region. They would soon be swallowed up by the Red Army and shipped off to POW camps, from which very few would return.

Operation Hannibal was the most successful operation conducted by the Third Reich in the latter stages of the war. A crippled Kriegsmarine that had mostly been swept from the sea rose to the occasion one last time. The operation cost the Germans four large passenger liners and 157 other vessels but not a single major warship.

Taking the half-full view, it Operation Hannibal saved up to two million Germans from internment or worse, but it did not save the mass of Germans in East Prussia. In 1940, East Prussia was home to 2.2 million Germans. By the end of May 1945, that population had been reduced to 193,000 desperate, starving people.

Still, Dönitz was justifiably proud of what Operation Hannibal had accomplished. Writing in his Memoirs 10 years later, he said, “Ninety-nine per cent of the refugees brought out by sea succeeded in arriving safely at ports on the western Baltic. The percentage of refugees lost on the overland route was very much higher.”

Of an estimated 200,000 who fled west by land, untold thousands died of exposure and Soviet bombs and strafing. Of those taken off by ship, the best estimates are that only three percent died at sea. It is easy to focus on the losses at sea like the Wilhelm Gustloff’s 7,000+ deaths, but Operation Hannibal was a remarkable success story attributable to German ingenuity, determination, and more than a little luck. It was a credit not to Nazis ideology but to old-fashioned classic German efficiency.

In the end, Operation Hannibal deserves to be recognized as a magnificent logistical accomplishment, ranking ahead of the British evacuation of Dunkirk in 1940, the American flight from Corregidor in 1941, and the failed Russian withdrawal from Sevastopol in 1942.

Dear Mr. Selcer, your masterful article on “Operation Hannibal” was a pleasure to discover and read. It is indeed a story of major historical importance that is too little known in Europe (I was born in Belgium) and the United States (I have lived in the USA for four decades). Though I made my career on Madison Avenue, I have always been a History buff. And now I am a published author currently hard at work on the biography of a man who was born in Munich in 1927, and aboard the KMS Lützow from January 2 to the morning of April 16, 1945, hours before it was sunk! By sheer luck, he was on a overnight hospital leave when the Allied bombers arrived at 5 pm that fateful day.

And here I must point out to probably the only major inaccuracy in your article: There is no such thing as a “671 USAAF bomber squadron.” The 18 bombers that attacked the KMS Lützow on April 16, 1945, were actually RAF Lancasters from “Squadron 617” of “Dam Busters” fame, half of them carrying the five-ton “Tall Boy” earthquake bomb. The Lützow was not hit directly, but a near-hit ruptured its hull, resulting in its settling on the shallow sea floor of the Stettin Lagoon, leaving its deck 8 ft. above water. The front turret had been damaged, but the rear turret and most of the other guns were intact. After quick repairs, the crew resumed firing its three remaining 11″ long range guns on the Soviet formations attacking Stettin! They ran out of ammunition on May 4, and abandoned ship. This version is verified by multiple sources, including Wikipedia Deutsch and military.wikia.org, backed by the written testimonial of the my biography subject. The eldest of his four sons (all born in America) is my key source here.